Atrial Septal Defect

During fetal life communication between the two atria is essential for the fetus's survival. The foramen ovale, through which blood enters the left atrium, is protected by a valve that permits flow only from right to left. At birth, when pressure in the left side of the heart rises after the newborn takes its first breath, the foramen ovale ceases to function. Ordinarily it seals itself off, but even in cases when the sealing fails to occur, the valve does not permit it to function

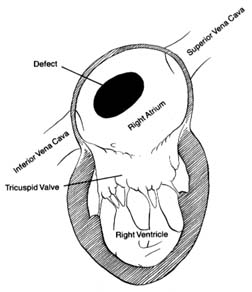

Figure 35. A typical atrial septal defect

as a pathway for blood flow. Atrial septal defect is an abnormal opening, usually located in the region of the foramen ovale, but larger and wide-open, allowing large quantities of blood to flow from the left to the right atrium (fig. 35). The quantity of blood shunted through this communication varies according to the size of the defect and the capability of the right ventricle to accept the additional blood. Small atrial shunts have no serious effect on the circulation since left-to-right shunts do not reduce the oxygen content of the blood. Large shunts, however, can overload the right side of the heart and increase blood flow through the lungs as much as fourfold. Normally each heartbeat ejects from each ventricle into the respective arteries (aorta and pulmonary artery) an average of 75 cc of blood. In the case of a large atrial septal defect right ventricular ejection may increase to 300 cc, and left ventricular output remains normal; hence 225 cc of blood returns to the right side of the heart during systole. This is referred to as a four-to-one shunt (a ratio of pulmonary to systemic output). A large shunt not only overloads the right ventricle, producing its hypertrophy and dilatation, but the wear and tear on the small arteries in the lungs may damage their inner layer, which in some persons can lead to high pressure in the

pulmonary arterial circulation. Pulmonary hypertension develops in about 15–20 percent of patients with atrial septal defect, almost always as adults. It may progress to the point where pressure in the right side of the heart exceeds that in the left, reversing the direction of blood flow from right to left through the shunt.

An atrial septal defect generally goes undetected until late childhood, adolescence, or even adulthood. The reason is that the flow through the defect between two low-pressure chambers does not produce turbulence audible as a murmur on physical examination. The child grows and develops normally (no cyanosis is present), except that the increased blood flow through the lungs raises susceptibility to respiratory infections. The diagnosis may be suggested on physical examination in older children by certain subtle abnormalities, but it is usually made when a chest X ray is taken, showing an enlarged heart and full blood vessels in the lungs. Confirmation of the diagnosis comes from echocardiography and cardiac catheterization, which reveals the magnitude of the shunt and the presence or absence of pulmonary vascular reaction (hypertension).

The course of atrial septal defect usually creates only minor problems. Development of the affected child is usually normal, although sometimes growth may be slightly impaired. Tolerance for exercise may be below average but seldom to the point of suggesting some disability. Frequent respiratory infections may occur. Persons in whom the defect is not surgically corrected may not develop significant symptoms until the fourth or fifth decade of life—sometimes even later. Reactive pulmonary hypertension, affecting one out of five patients with atrial septal defect, usually appears in early adulthood.

The treatment for atrial septal defect is surgical closure. This is one of the simplest cardiac operations, but it does require a pump-oxygenator. The operation is usually performed in older children or adolescents. Because of the risk of pulmonary hypertension it is best to close the defect before the age of 20. Closure of atrial septal defect is almost always a prophylactic operation performed on asymptomatic patients. If pulmonary hypertension is already present, closure may no longer be effective in preventing its progression. If cyanosis develops, closure of the defect is contraindicated since pulmonary hypertension then becomes the principal abnormality, which the operation will not correct.

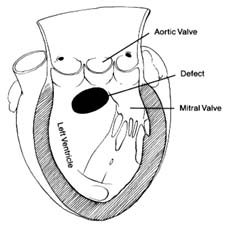

Figure 36. A typical ventricular septal defect.