PART III—

PERSONAL RULE

18—

The King in Council

As he turned his back on war and embraced a domestic happiness Charles could, with some justification, envisage a rosy future for himself and for his country. Economic conditions were on the whole favourable with the rate of inflation slowing down and prices rising less steeply than he could remember, while a general well-being among his more wealthy subjects was expressed in their willingness to invest in a wide variety of projects. The woollen industry, in particular, was responding to the marked improvement in trade which followed the end of hostilities with France and Spain and even the Mediterranean was receiving English cloth, sending back, in English ships, a plentiful supply of wine and oil, olives, dried fruit and raw silk. Moreover, as France and Spain drifted into a more open antagonism with each other and trade between them dwindled, England took advantage of the situation and reaped what Charles's sister termed an 'incredible profit' from the commerce that now flowed into English ports. Besides her own Mediterranean trade English ships took Spanish wool to Italy, Sicilian corn to North Italy and to Spain. Sugar from the West Indies was conveyed on the final stages of its journey from Portuguese and Spanish ports to the Mediterranean and to Northern Italy in English ships. English ships were hired by the Portuguese to bring sugar from Brazil to Europe. Even Venice was hiring English vessels. Charles had only to look down from his wife's palace at Greenwich onto the veritable forest of masts in the river below, or take one of his frequent journeys by barge down river past the bustling wharves that lined the Thames, to feel the beat of a commercial nation. Increased trade induced merchants, including the Merchant Adventurers, to put profit before principle and concede tonnage and poundage. Now was the time to make better bargains with the customs farmers. In 1634, guided by Weston, Charles increased the rent of the

Great Farm by £10,000 to £150,000 a year, and amalgamated three of the petty farms at an enhancement of £16,000 a year so that they brought him in £60,000 annually. At the same time, again with Weston at his elbow, he revised to his advantage the Book of Rates. In the same year, in return for a loan of £10,000, he confirmed the 'ancient privileges' of the Merchant Adventurers, which had been under attack from several parliaments.

His relations with the East India Company were less fortunate, which was a pity because, in spite of Dutch rivalry in the East Indies and antagonism at home, the Company continued to expand, and its import trade and re-export trade in pepper and spices, silks and calicoes, was very profitable. Its great galleys — 'like moving sea fortresses' — served the double purpose of war and trade. But neither Charles nor his father had felt it politic to take a firm line with the Dutch and to demand compensation for the massacre at Amboyna in 1623, and the loan of £10,000 for which he asked the Company in 1628 was refused. It was a form of retaliation when in 1635 Charles sold licences to Endymion Porter, Sir William Courteen and others to trade to Goa and parts of the East Indies, himself taking shares in the enterprise. He was careful to avoid an open breach with the East India Company by directing the new licences to areas where the Company's writ did not run and was therefore extremely angry when he thought that a petition presented to him the following spring concerned Courteen's ships. He snatched the document from the unfortunate envoy's hand and was appeased only when he realized it again related to Amboyna. He had, he told the man petulantly, always resolved to be righted concerning Amboyna. Charles's impatience when thwarted was becoming more noticeable. In this case it could have stemmed from his knowledge that his East Indian enterprise was ending in failure.

Other old-established Companies like the Greenland Company and the Russian Company also benefited from the peace, and Charles sold a charter to a new African Company in 1630, while taking his share of the profits of them all at his customs houses. From the West he was garnering a harvest of trade from the English settlers who were establishing themselves on the Eastern seaboards of America and in the West Indian islands, and from the traders who were bringing home tobacco and sugar from the Southern states, timber and ships' supplies from the Northern. England had been among the first to settle the New World. Virginia on the American mainland, Bermuda and other West Indian islands had been colonised by Englishmen. In

1620 the Mayflower had reached New England, and now the route to the West was being travelled not only by Puritans for conscience sake but increasingly by merchants and business men with money to invest, by adventurers who had no money but hoped to make some, and by English vagrants, bound apprentice by some local JP to learn such skills as the new lands might require. Carolina, named after Charles, Maryland, named after Henrietta-Maria, Monserrat, Antigua, were settled in one way or another in the expansive 'thirties. To earlier trading companies Charles added the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1629, and the Providence Island Company in 1636. The New World also met some of what he considered his obligations to his friends and servants, and lands he had never seen, and of which he had scant knowledge, were lightly given away to courtiers and adventurers, sometimes twice over.

Charles was fully aware of the profit he could reap from these distant lands. Tobacco, in particular, promised to be particularly rewarding. Charles disliked 'the weed' with an intensity no less than his father's, describing it as 'a vain and needless' commodity 'which ought to be used as a drug only and not so vainly and wantonly as an evil habit of late times has brought it to'. It was nevertheless reasonable, if only for the sake of the planters, that he should allow a limited import into England and that he himself should reap the maximum benefit from doing so. His actions showed an effort to combine all three points of view. In 1627 he appointed Commissioners to buy Virginia tobacco and sell it in England on his behalf; he limited its import, under licence, to the Port of London; he forbade both the import of foreign tobacco and the planting of tobacco in England. The legislation was confused but it brought Charles £9000 a year in licence fees, while the tobacco colonies gained from a virtual monopoly and took no notice of Charles's hints that they should turn to more worthy production: he was, he told them, 'much troubled that this plantation is wholly built upon smoke'.

There were other ways in which the Plantations were in a unique position to help the mother country. When Charles had asked his Commissioners for Trade in 1626 to advise him as to what 'maie best advaunce the Trade of Merchandize and not hinder us in our just profits', it was partly the Plantations he had in mind. James had already ordered that their tobacco should be landed in England before proceeding to other countries and that it should be carried only in English ships or those of the Plantations. Charles in 1633 underlined

the policy by forbidding aliens to engage in any direct trade with Virginia, the chief tobacco colony. The lucrative carrying trade would in this way be kept in English hands, English ships and English men would be trained and ready for war, and the customs returns would gain. In his attitude to the Plantations, particularly in navigation policy, Charles was in line with the most advanced economic thought of his time: he was following a policy begun by his father, which would be built up into a system under the rule of his son, and which later generations would know as Mercantilism.

Commercially, Charles could see himself ruler of an expanding, enterprising and wealthy nation reaching eastwards and westwards to new trade and fresh settlement. When he turned to industrial development he perceived a restless, innovating society already breaking the bonds of the old craft economy, using machinery and employing capital on a growing scale. As the demand for coal grew at home and abroad, increasing quantities of capital were being injected into the mining industry and from Newcastle alone some 400,000 tons of coal a year were being shipped — a twelvefold growth in a century. Iron, tin, and lead mines were becoming deeper, and their output increased, as capital provided new techniques suitable to larger-scale production; the great blast-furnaces for smelting ore in the iron districts were in themselves visual manifestations of the expansion that was taking place in the heavy industries.

There were factories with water-driven mills for making paper and hemp; the Mines Royal and the Society of the Mineral and Battery works, which Elizabeth I had established in an endeavour to produce brass and copper, were receiving fresh infusions of capital. There were large alum houses at Whitby, of which his father had been particularly proud, where many thousands of pounds were sunk in smelting machinery and many hundreds of workmen were employed. Round his capital city little factories were springing up and expanding as machine production began to oust the domestic worker in numerous enterprises such as brewing, soap-making, tanning, and the production of saltpetre. Above all, the woollen cloth industry, a highly organized, capitalist enterprise, still accounting for eighty per cent of the country's exports, remained its greatest asset, making all Europe, it was said, England's servant since it wore her livery.

In agriculture the disturbances caused by turning arable land and common grazing land into sheep runs were dying down and a new

equilibrium between arable farming and sheep farming was being achieved. The unenclosed strip-farming of the open-field villages found fewer advocates as a new scientific approach to agriculture, depending upon single ownership and enclosure, and stimulated by a growing demand, began to make headway. The yeoman was still the backbone of English farming. He was the owner-occupier, hardworking, good-living, unostentatiously prosperous — but perhaps he was a little less self-contained, a little more conscious that he was 'a gentleman in ore', a little more inclined to think of his coach on Sunday rather than his plough on Monday. Above him in the social hierarchy many gentry families were likewise thinking of the Great Estate, and if they sometimes were reduced to yeoman status there were others who, by judicious marriages and preferment at Court or in office, joined the aristocracy within a generation or two. The repetition, both in James's and Charles's reigns, of Proclamations commanding gentlemen to return to their homes in the country, indicates that a considerable number of them spent their time in and around the Court seeking, if not office itself, then some of the less lucrative spoils of office.

But there were many landowners of all ranks who remained in the country and concentrated upon improving their estates. Agricultural writers found a ready market for their books and there were many translations of Dutch and Flemish authors. The sowing of seed in regular rows instead of broadcast, and the use of fertilisers and manures were actively discussed. There were experiments with new crops such as rape for cattle feed and oil, saffron, woad and madder for dyeing. Potatoes and clover were being introduced as field crops, and both turnips and clover were being used experimentally as part of a three-year rotation that would replace the customary third fallow year. Advice was published on the raising of cattle and sheep, on the care of horses, on bee-keeping. The perennial question of the conservation of woodland was being widely discussed. Methods of drainage and water supply were assuming a new importance.

Behind the experimentation, the new techniques, the popularization, was a rising, vigorous population demanding food. Since the accession of James the population of England had risen from about 3,750,000 to some 5,500,000, nearly twice as fast as in the previous century, a growth particularly marked in the ports, the towns, and — above all — in London. Capital city, port, financial centre, seat of government, home of the courts of law, of art, and of fashion, the

normal abode of the Court, London was the magnet that drew trade and production, money and population into its orbit. Charles's London had reached a total population of some 600,000 people. Bristol was thriving on the opening of the Atlantic trade, and her rising population was somewhere around 25,000; Norwich and Exeter prospered on their textile manufacture; Newcastle as a port and the chief coal town was growing rapidly; but none could touch London for its bustling, overflowing exuberance. There was inevitably criticism but the rest of the country, by and large, saw where its advantage lay and did what was necessary to supply so opulent a market.

To keep London warm Newcastle colliers plied a constant coastal trade. To feed it corn came not only from Kent but from as far afield as East Anglia and Norfolk. Cattle on the hoof made their way from breeding grounds in the south-west to be fattened on nearer meadows before proceeding to the butchers of London. Poultry farms, pig farms, dairy farms, orchards and market gardens flourished round the capital city, stretching along the Thames and down into the fertile fields of Kent. There were apples in great variety, pears, cherries, plums, greengages, quinces, and mulberries from the trees which James, shortly after his accession, had caused to be planted near the capital and in each county town. Sir Walter Aston, who had been Ambassador to Spain in Charles's courtship days, was now Keeper of the Mulberry Gardens at St James's (and of the silk worms which were the reason for planting mulberries) at a stipend of £60 a year.[1] Henrietta-Maria added to the abundance by sending to France for fruit trees to enrich the English orchards. Well-off Londoners prized particularly the delicate asparagus provided by nearby market gardens. The Thames itself, besides watering the gardens and orchards on its banks, provided its own delicacy in the form of salmon. Herrings — salted, smoked, or packed in salt — might come from Yarmouth, and were enjoyed by rich and poor alike; but the wealthy valued above all the salmon from London's river, the more so, perhaps, since of all the City's food the salmon alone failed to keep up with demand and in the 1630s its price was soaring.

On the whole economic conditions were so favourable that Charles failed to see why he could not wipe the slate clean and, free from wars and foreign commitments, start afresh. In ruling without a Parliament he would not be doing anything unusual. Henry VII held only seven Parliaments in a reign of twenty-four years. Elizabeth I had ruled

without a Parliament for periods of three-and-a-half, four, and four-and-a-half years, and had stretched intervals between sessions of a single Parliament to nearly five years. James had governed for as long as six-and-a-half years without a Parliament. History taught Charles that the summoning of Parliament had for the most part coincided with the monarch's financial needs — the warring Edward III had called forty-eight Parliaments in the fifty years of his reign — and this reinforced his determination to pay his debts and avoid war. He recognized the strength of Wentworth by making him Deputy Lieutenant of Ireland in January 1632, while not depriving him of the Council of the North. At home he would be advised by the great officers of state — the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Privy Seal, the two Secretaries of State, the Chancellor of the Exchequer and, above all, by the Lord Treasurer. They all had seats on his Privy Council which, besides its advisory function, was also his chief instrument of government and would promulgate the Orders in Council which would take the place of Acts of Parliament. He was accustomed to the workings of the Council, which he had attended assiduously in times of stress both as Prince and in the early years of his reign: in the crisis months of 1627 and 1629 he had attended practically weekly. Among other things he had learned the disadvantages of size and in the first five years of his personal rule Charles reduced the number of his Privy Council from 42 to 32. But even thirty people form an unwieldly vehicle for discussion, some Councillors naturally proved more useful or more congenial than others, and there developed an inner committee of the Privy Council, sometimes referred to as a 'junta' or 'cabinet council', where Charles and his closest associates could determine policy before putting it to the Council as a whole.

The Privy Council met normally on Wednesday and Friday afternoons, generally in the Council Chamber in Whitehall, but sometimes in Wallingford House, the seat of the Treasury and the residence of Weston.[2] There were various standing Committees of the Council which Charles had appointed, or which he had continued from his father's reign. The standing Committee for Trade was important and Charles attended frequently, enlarging it to become the Committee for Trade and Plantations, and the importance of the colonies was further recognized in 1632 by the appointment of a Committee of Council on the New England Plantations, which became the Commission for Foreign Plantations in 1634. Reports came to Charles not only from these standing Committees but from various Departments

of State — from the Admiralty, in particular, at whose meetings he was, again, a frequent participant and whose reports he read carefully and annotated repeatedly. He extended his care to the Provinces of the Church, reading and making marginal comments on the Reports that came in from the Bishops. He kept his hand on foreign affairs to such a degree that Sir Thomas Roe was able to write to Wentworth in December 1634 that it was only the 'great temper, justice, and wisdom of his Majesty' that corrected and dispersed ill humours. He insisted on personal consultation in all matters. Edward Nicholas, the secretary to the Council, listed the points on which Charles was to be consulted and afterwards noted the results of the consultation: 'The King approves of this'; 'The King likes it well but . . .' His ministers knew they could consult him at almost any time on important issues, as when Henry Vane arrived at Hampton Court after six o'clock one evening on Palatine business. Weston was early instructed by Charles 'to believe nothing of importance until he speaks with his Majesty'.

The machinery of the law remained the same whether Parliament was sitting or not. Chancery, King's Bench, Common Pleas, Requests, continued their normal work; Justices of Assize made their circuits; the courts of Star Chamber and of High Commission, the Councils of the North and of the Marches of Wales maintained their authority. The Departments of State were no more efficient, no more corrupt, without a Parliament than with one, their staffs still remained dependent upon some form of perquisite or bribe to augment their salaries. In the localities, at the operative end of most laws or directives, it was still the JPs upon whom Charles would have to rely. They were men of diverse character, interest, and determination, most of them were of gentry or aristo-gentry stock, and they included many of the most influential members of Charles's last Parliament some of whom, including Sir John Eliot, were still in prison for the part they played in the dissolution. It was a disturbing thought that his government might be only as effective as these men made it. But, though Charles instituted several enquiries into central administration he left local government untouched.

Charles was prepared to thrust such thoughts into the background as he turned to the immediately pressing problem of his debts. The question was not quite so straightforward as at first appeared, partly because of the size of his commitments, which included some of his

father's debts as well as his own heavy war expenditure, partly because of the complicated system of borrowing and credit in which he was enmeshed. It was difficult to establish the full extent of his indebtedness, but it could have been of the order of £1,500,000, of which the faithful Burlamachi was claiming £500,000. Most of Charles's foreign transactions had gone through Philip Burlamachi, whose credit stood pledged all over Europe to meet Charles's needs. Burlamachi supported Mansfeld's expedition in this way, he paid Charles's subsidies to Christian of Denmark and other Princes, he transmitted to Germany sums of money voluntarily collected in England for the cause of the Princess Elizabeth, he paid for the Mantuan collection of pictures, he provided funds for foreign embassies, gave security to agents of the Crown abroad, paid pensions to the Palatine family as well as advancing money for men and equipment at home. Charles was fortunate in having in his service one of the great international financiers of the age whose word and whose credit were unquestioned from the time he advanced money for the little Duke's engines of war until he himself crashed in 1633.[3]

On domestic loans Charles normally paid the current rate of interest, which was eight per cent after 1624. Borrowing was generally secured upon the receipts of the Exchequer in general or upon specific branches of the revenue, collectors being instructed to honour debts out of the proceeds of their collections before the money reached the Exchequer. In either case over-assignment was not unusual, nor were the persons who received money in this way necessarily those who made the loan in the first place. The tallies which represented debts often became a kind of currency in themselves, passing from hand to hand at a decreasing price until they reached a person who knew how to get them cashed at a favourable rate. It was difficult for Charles to know how many tallies were circulating against him. At the same time, with interest accumulating, the more he struggled the more securely he was enmeshed. By August 1630 future revenue stood mortgaged to the extent of nearly £278,000, with some revenues anticipated to 1637.[4]

Charles and Weston faced the question squarely: Crown lands were given or sold on reasonable terms to recoup debtors, the City of London alone receiving nearly £350,000 worth in settlement of debts incurred by James. Holland, the King's friend, was promised a pension of £2000 a year for twenty-one years, possibly in respect of some £23,000 still due to him for his expenses in France when he was

wooing Henrietta-Maria on the King's behalf. Royal jewels passed to other creditors. Two men were satisfied with the imposition of a new duty of 4/- a chaldron on seacoal which they were allowed to manage until their debts had been met; others were promised the reversion of fines imposed in certain courts. In addition, about £100,000 was paid out in cash during 1630 and 1631, a great deal of which came from the customs' duties which, enhanced by Weston's new Book of Rates, were now Charles's most important source of revenue. They remained, also, a continued means of anticipating income and were Charles's chief source of borrowing in the 1630s. Burlamachi, in spite of some slightly questionable accounting, received his £500,000 in various forms, but it was not enough to save him from the effects of twenty years of financial juggling. When everything blew up in his face in 1633 Charles showed his customary concern for a man who had been faithful to him for more than a decade. He helped Burlamachi with money and gave him the administration of the alum farm. A few years later he appointed him Postmaster. But Burlamachi was too deeply enmeshed to pull himself clear and he died in penury some ten years later.

But, debts apart, how could Charles make ends meet without the subsidies which only a Parliament could sanction? He totted up his responsibilities: payments to staff and servants of various kinds, including those who served him in high office; he felt keenly his obligations both to their standards of life and to their pensions. He honoured his father's intentions (which were also his own) towards Buckingham by providing for Buckingham's wife and children. He helped Weston who, on accepting the Treasurer's white staff made it clear that he could not support the dignity of the office out of his own means. Charles gave him £10,000 in cash and made over to him such perquisites as the lease of the sugar farm, amounting to approximately £9000 a year, and a third part of the imposition upon coals, some £4000 annually. The Queen, with an extravagance and way of life dictated by her upbringing and her temperament, required well over £30,000 a year. Charles had already added lands in the Duchy of Lancaster to her jointure and in 1629 he included various parks nearer home at Greenwich, Oatlands, Isleworth, Edmonton and Twickenham, as well as the manor of Holdenby in Northamptonshire.

There was also a pleasant need for additional expenditure on the royal nursery, where Buckingham's children were now established with his own. He felt his obligations to his nephews and nieces and in

1629 extended to Repert and Elizabeth the pensions already paid to their mother and elder brother. The giving of presents was a part of life and in 1630 Charles presented the Savoy Ambassador with a gold tablet set with diamonds bearing a picture of himself and the Queen, valued at £500; in 1636 he and Henrietta-Maria gave horses worth £500 to her brother, the King of France, and made a similar present to his sister, Elizabeth. He himself, though he economized in dress, bought for £300 a ring set with a large, square diamond, and in 1634 he was fondling a 'great round rope of pearls' which had been imported duty free for his inspection. He paid £110 to Michael Crosse for copying pictures in Spain; early in 1631 he employed Inigo Jones to catalogue his Greek and Roman coins and medals; he counted himself fortunate in getting the French engraver, Nicholas Briot, to provide engravings for the English coinage and to produce such beautiful pieces as the medals which marked his Coronation and his claim to Dominion of the Seas.

In 1629 Charles sent the Gentileschis to Italy with a view to buying the picture collection of Signor Philip San Micheli, subject to the approval of Nicholas Lanier. Fortunately for his Exchequer Lanier advised against the purchase. Eight years later, however, Charles purchased the Italian collection of the German artist, Daniel Fröschl, who had been painter-in-ordinary to Rudolph II, thus adding twenty-three pictures to his collection, including six grisailles attributed to Caravaggio, and canvases by Titian and Guido Reni. He bought, as Rubens had recommended, the magnificent Raphael cartoons and sent them to his tapestry workers at Mortlake. True, what he bought or what he commissioned was not always a guide to what he paid. In 1638 payments were still being made to Rubens in respect of £3000 due to him for pictures sold to Charles 'long since'; the chain of gold which Charles sent him in March 1639 may have been in part recompense, but it may have been in acknowledgment of the Banqueting House paintings which were delivered in 1637. Charles welcomed, even urged, Anthony Van Dyck to reside in London as Court painter but Van Dyck's payments also lagged both in respect of his retainer and for the portraits he painted of the royal family. Gentileschi was still installed in York House in 1631 refusing to move until he had received what was owing to him, while the Duchess of Buckingham entreated the King to pay him so that she might have York House to herself again. Charles paid £200 to the artist who, in due course, moved on.

Other expenses were more difficult to justify. Even though

Weston was serving him well and the memory of Buckingham was green, was it necessary to give £3000 to Weston's daughter on her marriage to Lord Fielding, the Duke's nephew? Or £3000 to Lady Anne Fielding, the Duke's niece, on her marriage to Baptist Noel, Viscount Camden's heir, who, in gambling, lost in one day a nearly equivalent sum?[5]

It was difficult to know where retrenchment should begin. Charles had nineteen palaces, castles and residences to keep up which required renovation, repairs and replacements, as well as a permanent nucleus of staff. Hunting at Newmarket, in the New Forest and elsewhere cost money even when entertainment was provided, as at Wilton, by the King's friends. But Charles's passion for the chase now equalled that of his father, and it kept him in health. Nor could the Queen's visits to the spas at Bath or Matlock be curtailed. He not only needed money for his pictures and works of art but, with Laud and Inigo Jones, he had schemes for beautifying his capital, including the rebuilding of St Paul's, which his father had begun. London's cathedral was in a ruinous state, its steeple had been destroyed by fire at the beginning of Elizabeth's reign, ramshackle shops and houses leaned against its outer walls damaging the fabric and destroying the proportions of the nave. Inside it was given over to strollers and gossip-mongers and 'Paul's Walk' was the commonly accepted resort of anyone anxious to purvey or to receive news. The case of Francis Litton illustrates its condition. Litton came up from a remote village three miles from Bedford to London to be married and was apprehended by the High Commission for 'pissing against a pillar' in St Paul's. The bewildered countryman explained 'he knew not where he was' as he had never been in London before, and 'knew it not to be a church'; also he suffered from the stone and was unable to make water when needful yet at other times 'he could not hould but must needs ease himself'. The pillar of the church appeared to him nothing but the most convenient place for doing so. When he fell down on his knees and wept before the Commission, pleading that he was far from his friends, the court granted him bail and presumably released him.[6]

When Laud, as Bishop of London, asked Charles in 1631 to continue the work his father had begun, Charles was only too ready to do so. He visited the Cathedral himself, appointed Commissioners to collect money for repairs, put Inigo Jones in charge of the overall plans. In spite of exhortation and Charles's own example of pledging £500 a year for three years, not much more then £5000 was collected

over the next two years, but Charles had already instructed the work to proceed and most of the houses built against the walls of the church had been demolished. There had been objections, but compensation had been paid, and the splendid proportions of the long nave were revealed. Jones's plans now included a classical portico at the west end of the church, and when Charles visited it in the summer of 1634 he was so pleased with the progress of the work that he undertook the whole of the western end at his own expense.

In other directions expenditure was more questionable: improvements to his manor of York; the conversion of a tennis court at Somerset House into a chapel for Henrietta-Maria; above all, the making of a new deer park between Richmond and Hampton Court. Much of the land involved was Charles's own, and a great deal of it was waste and rough woodland which would benefit from his plans. But many poor people held common rights in these areas and more substantial men held good, working farms interspersed with the waste. Charles's intention was to buy out these landlords and to put a brick wall round the whole of the area he acquired. Some landlords agreed to his terms, some held out, reluctant to abandon their homes and their estates, the poor were upset at losing their common rights. Most of Charles's ministers, including Laud and Cottington, disapproved of a scheme which would cost a lot of money and alienate many people. In the high-handed way in which he was now conducting all his affairs, Charles disregarded them. Cottington, however, was very outspoken and Charles's anger flared: he had caused brick to be burned for making the wall, he said, and was resolved to go on with the scheme. Laud assumed he had an ally in Cottington and when the application for money came before the Treasury Board stoutly opposed it. But Cottington, either because he wished to keep the King's favour, or because of his antipathy to Laud, spoke in favour of the grant: 'since the place was so convenient for the King's winter exercise, it would minimise his journeys', he said, 'and nobody ought to dissuade him from it'. Laud flew into a passion, telling Cottington that such men as he would ruin the King and cause him to lose the affections of his subjects. Cottington taunted him: 'Those who did not wish the King's health could not love him; and they who went about to hinder his taking recreation which preserved his health might be thought . . . guilty of the highest crimes.' He was not sure that it might not be high treason. Laud rushed to the King, but Charles merely laughed, at once perceiving Cottington's intent both to curry

favour with him and to tantalize Laud. 'My Lord', he said, 'you are deceived: Cottington is too hard on you,' and he told him of Cottington's opposition to his plans. Charles's New Park at Richmond was begun in 1636 and completed in 1638. But Charles forgave Laud more easily than he forgave Cottington for opposing him.[7]

19—

Modern Prince and Feudal Lord

Economies like cutting pensions and reducing Court expenditure, extravagance like the making of Richmond Park, create enemies, but on the whole the raising of money makes more. Weston was more aware of the difficulties than Charles himself. He was already stepping up the receipts from the customs houses in what was likely to be the biggest contribution to the King's finances, but his natural caution enabled him to foresee danger in some of the other money-making devices that Charles was contemplating. A Treasurer whose influence was on the side of caution was bound to have some effect upon the King, yet Charles was never deflected from any purpose he had in mind: he simply used other instruments if one failed him. The influence of Laud was less direct. His natural austerity acted as a break upon expenditure, his urge to improve the King's finances caused him to press economy and pursue money-raising devices with a ruthless integrity. Unlike Weston, he seemed utterly impervious to the dangers of arousing vested interests.

In the raising of money by the sale of monopoly rights in various forms Weston was particularly cautious, while Charles was at his most expansive, carrying his Council with him into an amazing series of projects. The granting of monopoly rights of production, sale, or management in return for a fee or rent had become a scandal even in Elizabeth's time and James had agreed to the abolition of the practice. The Monopolies Act of 1624, however, allowed two exceptions which were in accord with public sentiment. The first was in respect of new inventions or infant industries where it was considered reasonable to allow a period of monopoly protection. The second was in respect of corporations. Seventeenth-century opinion was still widely influenced by the medieval concept of the corporate society in which trades and trading bodies, towns, religious organizations and

fraternities were organized on a corporate basis and acted as monopoly bodies. To have pronounced these illegal would have been to remove the underpin from society itself. So, in spite of abuses, corporations remained, with new inventions, outside the scope of the Monopolies Act. That Act, however, had not intended, and could not have envisaged, the mushroom growth of patents and monopolies which came into being under cover of these exceptions.

A Crown monopoly of playing cards and dice gave the King a fifty per cent profit on sales. Monopoly rights to individuals included the transport of lamperns, the making of spectacles, combs, hatbands, tobacco-pipes, bricks; there were monopolies for the gathering of rags, for sealing linen cloth and bone lace, for gauging butter casks, for transporting sheepskins and lambskins. Sir William Alexander was given a patent for printing the Psalms of King David translated into English metre by King James. The rights were all paid for in one way or another. John Pearson and Benjamin Monger of London 'set forth the inconveniences and mischiefs which arise from dishonest servants, and the impositions practised by charewomen and dry nurses'. They proposed a Register of Masters and Servants, the fee being 2d from the master and 1d from the servant, and they offered the King a payment of £10 a year for the privilege of the sole running of the registry.[1] Charles liked the idea and the project was approved. Somewhat different was a scheme proposed by Sir John Coke, which never saw the light of day, for the formation of a Loyal Association, whose members, besides paying an entrance fee, would pledge themselves to serve the King in person, goods, and might. They would be distinguished by a badge or ribbon in the King's colour and would be entitled to precedence at public gatherings.[2]

Frivolous or lightweight as most of these projects appeared, others were in line with an economic self-sufficiency that for hundreds of years had been the goal of the King's ancestors. Elizabethan statesmen, as well as his father, had pursued this end and many of his own most influential subjects were urging its necessity. Mansell's glass patent, which Charles renewed, might be considered in this category; the alum works whose monopoly Charles continued, certainly could be; when Sir Thomas Russell was licensed to use a process of his own invention in the production of saltpetre, Charles was following the lead of Elizabeth and of James; a crown monopoly of the sale of gunpowder followed naturally and, besides being profitable, could be justified on grounds of national security. The saltpetre monopoly ran quickly

into difficulties when the Admiralty learned that some saltpetre men were being over-zealous, abusing their rights of search for the raw material by digging in barns and churches, houses and sick-rooms regardless of the old, the sick, and women in childbed, undermining walls and making great holes which they failed to fill up. But the Government needed saltpetre and Charles caused a Proclamation to be made in 1634 empowering any three or more JPs to 'enter, break open, and work for it in the lands and possessions' of himself or of any of his subjects in England and Wales.

In incorporating William Shipman and others as the Society of Planters of Madder of the City of Westminster, he was again following the lead of his father, who had already attempted to restrict the import of this important dye in order to render the cloth industry more self-sufficient. In turning his attention to salt, seeking to substitute a native product for the imported article, Charles was pursuing the same well-trodden path towards self-sufficiency. In 1636 he prohibited the import of salt from Biscay and issued licenses for its manufacture and sale in England, hoping to receive ten shillings a wey for his support and protection. Unfortunately the contradictions inherent in the policy of self-sufficiency were glaringly obvious in this case: the price of salt rose and affected the fishing industry, particularly the important herring fishery, which depended upon salting its catches; Trinity House complained that ships which had formerly brought back salt from Biscay now returned unladen from the south of France and might be compelled to abandon their voyages altogether; while the benefit Charles received from the granting of licenses was partly offset by his loss of duty on the imported product.

The patent for soap demonstrated the same mixture of motives as well as providing one of the most colourful episodes of the time. Again the project had been aired in James's reign and was an attempt to raise Crown revenue while promoting self-sufficiency. Foreign soap was excluded and the home-produced article was to contain nothing but native materials. To this end a group of soapboilers was incorporated in 1631 as the Society of Soapmakers of Westminster, and was instructed to use vegetable oil in place of imported whale oil. This obligation extended to all soapboilers and its enforcement was put in the hands of the new company. To make control easier the production of soap was confined to London, Westminster, and Bristol. The new Society thus held a virtual monopoly of soap manufacture, and in order to protect the consumer the price was fixed. The King was to

receive a payment first of £4, later of £6 a ton of soap marketed. But the public did not like the new soap, and the old was soon selling at higher prices as independent soap boilers continued to produce clandestinely. They were called before the Star Chamber but neither their punishment nor testimony from selected witnesses, including the Queen's laundress, could convince consumers that the new product was as good as the old; rumour, indeed, had it that the Queen's laundress continued to use Castille soap. Public laundry trials organized in the City of London gave conflicting views on the efficiency and 'sweetness' of the new soap; as a final throw the independent soap-makers offered the King an annual payment of more than the new society was paying and the monopoly was bought out. But these operations enhanced the price of the product and, although Charles continued to reap as much as £18,000 in 1636, the best year, his subjects were the losers.[3]

Charles made no attempt to control any basic industry. A government monopoly of coal was considered but the Committee for Trade advised against this on the grounds that it would raise the price and arouse the 'clamour of the people'. It would also have meant confronting the powerful monopolists who already controlled the industry and who doubtless had influenced the verdict of the Committee. If it could have been managed, control of a basic industry would not only have been financially advantageous to Charles but would also have bolstered the aim of economic self-sufficiency which, as it was, appeared to be pursued in somewhat piecemeal and haphazard fashion.

Trading monopolies had, on the whole, even less to say for them. The Company of Vintners, for example, paid to the King a duty of 40/- a tun of wine sold in return for monopoly rights of sale and an increase in price of one penny a quart on French wines and twopence a quart on Spanish wines. Charles farmed the tax to a group of vintners for £30,000 a year, but it is doubtful whether he ever received as much as this.

The group of projects which covered inventions was mixed. In agriculture there were many schemes for drainage, several inventions for mechanical sowing and for improved ploughs. A patent for the much-needed cleansing of the Thames did more harm than good in scooping up gravel from the river bed 'and making great holes'. In view of the feared shortage of timber it was, however, timely to give a fourteen-year patent to Dud Dudley and his partners for smelting iron

with coal, or with peat or turf, in return for an annual rent; it was reasonable to license Edward Ball to prepare peat by reducing it to a coal that would 'serve for melting iron, boiling salt, and burning brick'. The many new patents for the drainage of mines, like that granted to Daniel Ramsay and his associates 'for raising water out of pits by fire' showed, possibly, a too-credulous belief in experiment. Sir Henry Clare, searching for the philosopher's stone, strained that credulity too far and Charles turned down his request for financial aid. There was, however, a lively interest in hidden treasure. In April 1630 Francis Tucker and his associates were given licence to conduct such a search on the understanding that Charles received one-quarter of anything they found. Two years later Charles listened to Richard Norwood who had 'found out a special means to dive into the sea or other deep Water, there to discover, and thence by an Engine to raise or bring up such Goods as are lost or cast away by Shipwracke or otherwise' and he licensed search in the water as on the land.[4]

Charles was present to hear the case made by Thomas Russell for the use of human urine in the manufacture of saltpetre. Russell estimated that if 10,000 villages, each with forty houses occupied by four persons who all cast their urine upon a load of earth for three months, and then let it rest for three months longer, ripe saltpetre would result. Feeling, perhaps, that this was a viable alternative to the ravages of the saltpetre men, Charles ordered all cities, towns, villages and other habitations to use their urine in this way, guaranteeing that the earth would be taken from them without trouble or charge,[5]

Charles and his Council were certainly attracted by anything out of the ordinary, and the exuberance and inventiveness of the time was encouraged by their support. Charles himself was genuinely interested in projects, and his eclectic mind enjoyed ranging over the schemes brought before him. He was eager, assiduous, hardworking, even if, together with his Council, a trifle over-sanguine and too ready to attempt to fill the royal purse at the expense of credulity. An Order in Council later lamented the various licenses which had been procured 'upon untrue suggestions' or which in execution had been found to be 'far from those grounds and reasons wherefore they were founded' and which proved 'very burdensome and grievous to the King's subjects'. Using the expression that James had used when things went wrong, they complained that they had been 'notoriously abused'.

Charles received a valuable income from his monopolies and patents: though less than £30,000 from wine rather more from the soap

monopoly: a useful £13,000 or so annually from tobacco licenses: a small but helpful £750 annually from his monopoly of playing cards and dice: rents from the alum and glass works: small sums from the various patents he sanctioned.[6] Several contemporaries asserted that he was being defrauded and received but a fraction of what was intended. More serious was the criticism that since there was nothing to prevent the fees which were paid to the King from being passed on, it was the consumer who paid the King's commission in the form of higher prices. A discriminatory excise on luxury goods could have brought in as much and caused less hardship to the poor though possibly more protest from the rich. Charles excused himself by remembering that England was still the least taxed country in Europe, with no official excise and no regular direct taxation. Certainly projects and monopolies were not the most efficient nor the most equitable way of raising money, but in the absence of any other form of taxation it was possibly more appropriate to criticise the nature of the project itself than the fact that it imposed a tax upon the community. A tax arising from the monopoly of an essential article like glass or soap was different from a tax imposed in order to foster a new technique in industry or agriculture. Taxes on playing cards and dice were annoying rather than burdensome to the public. The real abuses were taxes that affected industry and reacted on workers as well as their employers, the monopolies that rebounded against themselves by causing shortages and dislocation elsewhere. On the credit side were benefits like the infusions of capital which followed the new leases issued to the Mines Royal and the Mineral and Battery Works, the encouragement of the home production of the important wool cards by a prohibition of import; and there were other grants, restrictions, and prohibitions whose value depended upon the point of view, such as the prohibition of the use of brass buckles as being not so serviceable as iron. Obviously, in considering methods of raising money a line had to be drawn somewhere. Charles drew it by not debasing the coinage, by not taxing food, and, while allowing the price of wine to be enhanced, by not taxing the people's beer.

In a somewhat different category were schemes bequeathed to Charles by his father which concerned water supply and land drainage, both matters of concern to a growing population which required both water and food, and both possible means of channelling money into the Exchequer.

Sir Hugh Myddelton, a Welshman with a lively interest in affairs and with financial and other connections in the City where he practised his craft as jeweller, goldsmith, banker and clothier, was among those who had been considering the idea of a continuous supply of sweet water to London. He was a great friend of Sir Walter Raleigh with whom he would sit outside his goldsmith's shop, smoking tobacco and talking endlessly of projects and exploration while the London populace looked on. It was possibly then that the idea was born of channelling springs of fresh water from Chadwell and Amswell, near Ware in Hertfordshire, by means of an artificial waterway or New River to Islington on the outskirts of London, where it would flow into a reservoir to be called the New River Head. James already had dealings with Myddelton as a jeweller, and his curious mind was attracted when he saw engineers making investigations near Theobalds on Myddelton's behalf. In 1612 James agreed to pay half the cost of the works, past and future, in return for half the profit. The first stretch of New River was completed by 1617 when it was opened with considerable festivity and enthusiasm. James had by that time contributed over £9000 to the enterprise but profits were not high and in 1631 Charles commuted his inherited half-share to £500 a year.

But there were still many families in and near London without sweet and wholesome water or, indeed, without access to water for cleansing or for fire-fighting, and when in 1631 projectors claimed to have discovered new springs, hitherto unused, that could be channelled to London and Westminster along a stone or brick aqueduct there seemed no reason not to licence the undertaking. That Charles did so with care was an answer to those critics who blamed him for sanctioning 'rival' projects. The scheme commissioned in 1631 was supplementary to Myddelton's and its provisions were carefully laid down. In spite of Sir Hugh Myddelton's work, ran the caption to the grant, 'Wee are credibly informed that there are very many families, both within the Citty of London, and the suburbs thereof and Streets adjoining in the County of Middlesex, which want sweet and wholesome water to Bake and Brew, Dress their Meat and for other necessary uses, and cannot fitly be served or supplied with any the Water works which are now in use.' The licence was to bring water to London by an aqueduct of brick or stone from any spring or springs, pool or pools, current or currents, place or places within one-and-a-half miles of Hoddesden and to disperse it through several pipes, provided that hitherto untapped sources only were employed and that

their use did not 'diminish any of the Springs, or take away any of the Water' already brought to London or Westminster by Sir Hugh Myddelton. Charles's share of the profit was to be £4000 a year and he authorized the holding of a lottery or lotteries in any town or city of England to help raise money for the project. Lotteries were popular among his subjects — the more so since none had been organized for some time — and the tickets were soon taken up.[7]

Under the influence of the Dutch the reclamation of swamp and fenland by drainage had also been considered. Henry VIII had drained marshland at Wapping, Plumstead and Greenwich and there had been similar small-scale enterprises for an immediate purpose. But little as yet had been done to reclaim large areas of land where long-term planning and a great deal of capital would be required. An obvious target was the Great Level of the Fens which stretched inland from the Wash to cover an area of nearly 700,000 acres. It was watered by six rivers which overflowed their banks constantly in winter and frequently in summer so that throughout the year the area was a flat, watery plain where the inhabitants walked on stilts or travelled by boat. Fishing and fowling dominated their lives, yet when the waters retreated the soft earth was covered with lush grass for cattle and sheep, and there was always turf and sedge in abundance for firing, reed and alder for thatching and furniture-making.

The fiercely independent people who lived there were content with the life they knew and, with fish and fowl in abundance as well as cattle and sheep, a modicum of crops and the normal fare of the farmyard, they were probably better-off than many small farmers living more conventional lives. Even the less well-off among them were better placed than they would have been in a more organized society where they would be classed as sturdy beggars under the Poor Law. The basic wealth of the area was shown, indeed, by the churches, cathedrals and monasteries which had been raised over the centuries in stone brought from outside the fenland by barge down the many rivers. Naturally enough the possibility of drainage had been considered. But although the area was potentially rich and the prospects of profit were high, drainage was expensive, most of the inhabitants were content as they were and, apart from the bigger landowners, there was little interest in land reclamation. Particularly bad periods of flooding were dealt with by ad hoc Commissions of Sewers until the area reverted to its old life.

A growing population made the prospect of a larger farming area

more attractive, and James, dramatizing the situation after his own fashion, had announced that 'for the honour of his kingdom' he 'would not longer suffer these countries to be abandoned to the will of the waters'. Accordingly, he engaged the Dutch engineer, Cornelius Vermuyden, and sponsored the work of reclamation in return for 120,000 acres of the reclaimed land. James died before the work was begun but Charles carried on, at first content for local landowners to act as undertakers, putting up the money, shouldering the risk, and claiming their proportion of reclaimed land. But nothing came of this and in a welter of conflicting opinion, which included opposition to drainage itself and opposition to Vermuyden as contractor, the rivers got completely out of hand and several smaller owners of permanently flooded land approached Francis, fourth Earl of Bedford, who owned 20,000 acres near Thorney and Whittlesay, to help. In 1630 the Earl contracted to improve all the southern Fenland within six years so that it would be free of summer flooding. Thirteen others joined him in putting up the capital, Vermuyden was put under contract, and in 1634 Charles granted a charter of incorporation for the drainage of the Great Fen. Charles's fee for the charter was to be 12,000 acres of the drained land out of the 95,000 which would fall to Bedford.

By the autumn of 1637 the undertaking appeared to have succeeded and Charles received his 12,000 acres of land. But the work had been done against a background of opposition and rioting by the local population, not only because they feared to change their ways, not only because, in the reapportionment of land, many commoners lost their rights of pasturage and of fishing, but, more fundamentally, because the Great Level was an area which could not be stereotyped or subjected to any basic rule of thumb. Levels of flooding were different; some flooding was gainful; the prevention of flooding in some places merely inundated others which had previously been dry.[8] Charles saw nothing of this and he was obviously not familiar with the detailed geography of the Fens. Even Vermuyden, who planned and carried out the bulk of the work, lacked adequate topographical knowledge: both men could have relied more heavily upon local advice. Even so, Charles and his Council acquired a considerable understanding of the problems involved. Charles, for example, instructed the Commissioners of Sewers on the north-east side of the river Witham that, although their lands had been drained, it was necessary, in order to keep them dry, to maintain the river banks in repair between specified points. He showed care for the poor in instructing the Commissioners

in charge of apportioning land after drainage to convoy 2000 acres to the use of poor cottagers and others, and he was sufficiently astute to order a proportion of reclaimed land to be tied to the perpetual maintenance of the work.[9]

But when a way of life is disturbed, when outsiders make foolish mistakes, such concessions are unimpressive. All over the Fenland men and women came out with pitchforks and scythes to fend off the innovators. Sometimes a landowner of greater sophistication would offer a more durable form of defence as in 1637 when Mr Oliver Cromwell of Ely, in return for a groat for every cow upon the common, offered to hold the drainage commissioners of Ely Fen in suit of law for five years. But Charles himself intervened shortly afterwards. He was not satisfied with the way the drainage had been carried out for, although the Fens were now free of flooding in summer, they were still subject to winter flooding. After many complaints had been received by the Privy Council he stepped in personally, declared himself 'undertaker' and promised to make the Fens 'winter as well as summer lands'. Meantime he gave the inhabitants full rights over their lands and commons until the work was completed and the final apportionments made. Before that was accomplished both he and Mr Oliver Cromwell had been swept along by events even more important than the drainage of the Great Fen; when they came face to face it was upon other issues.[10]

Charles liked to see himself as an 'advanced' monarch, patronizing inventors and giving scope to innovation and improvement. But he was also aware of his position as feudal overlord and was as willing to raise money from the one role as from the other.

Already in 1626 he had appointed a Commission to consider means of augmenting his revenue and reducing his charges. Among the matters under review were his forests and chases and now, with the help of Weston, Charles considered them anew. These large, dispersed areas were not necessarily wooded but were technically land reserved for royal hunting. Their native inhabitants were few and largely itinerant with a way of life that was simple and not necessarily meagre. Though they were subject to forest law instead of common law, which entailed severe penalties for interference with the forest or its wild life, royal connivance had left them for the most part in peace to a life freer and more fruitful than that of many peasants elsewhere. The royal forests contained also a few settlers whose existence was

connived at. Even enthusiastic huntsmen like James had not used all forest land for hunting, and as forest laws had fallen into disuse many peasants had, in fact, used the forest amenities as they would those of ordinary woodland or waste and had even brought some of the forest area under cultivation. Forest verges, in particular, had frequently come under the plough. In this way the extent of forest land had been reduced and dwellings, in some cases entire villages, had grown up within the bounds of what were technically 'forests'. Here and there richer men, some already big landlords, were deliberately farming large stretches.

The suggestion now was that royal forests should be restored to their ancient boundaries and that transgressors should be fined for encroachment or for infringing forest law within that enlarged area. In this way practices that had come to be considered normal would be penalized, whole villages — there were seventeen of them in the Forest of Dean alone — would be subject to penalty for breaking forest law, and even those who farmed the verges would be fined. Though much of this would be small-scale penalization, and not intended to be carried out, the amount of discontent which the very idea would generate was bound to be considerable. It was, however, the big encroaching landlords who were the real target.

The ancient office of Justice in Eyre, which administered forest law, was revived for the purpose and in 1630 the Earl of Holland was appointed Chief Justice with the assistance of Lord Keeper Finch, the Speaker who had been held in the chair in Charles's last Parliament. Neither man was popular. It fell to Finch in the Forest of Dean, where Holland took up his Justice Seat in July 1634, to make the important pronouncement as to what were legally considered the ancient bounds of the forests and to what extent, consequently, infringement had occurred: the King's claim was to the boundaries as enacted by Edward I before subsequent amendment and he was, therefore, laying claim to the maximum area of forest land, despite the changes of three centuries.

As expected, the fines imposed upon forest dwellers or little nibblers were small or were allowed to lapse, and the main penalties were reserved for the big and wealthy landowners. In Dean, where the Lord Treasurer himself was implicated, one of the largest fines, of £35,000, fell upon Gibbons, his agent, who was commonly thought to be the scapegoat. Sir Basil Brooke and his partner, who were said to have used trees set aside for the navy for their iron works in the Forest, were

fined £98,000 jointly, which two years later was commuted to £12,000. Enormous fines in the New Forest, in Rockingham and other forests were similarly reduced but in all brought about £37,000 into Charles's Exchequer between 1636 and 1640. Frustration, indignity, and a sense of injustice festered. It might have been legally defensible to reassert a boundary three hundred years old, it might have been equitable that untaxed landlords should make some contribution to the royal Exchequer in respect of lands and profits which they had acquired by no right but custom. But to impose a fine which was so large that it was certain to generate the maximum resentment and then to remit or substantially reduce it, was a policy of ill-advised, deliberate confrontation to no purpose. Not that this always happened. There were cases when the project worked more smoothly and Charles was paid all, or nearly all, he expected.[11]

Besides dealing with the ancient bounds of his forests and chases Charles had asked the Commission of 1626 to recommend how he could restore parts of them to a 'profitable cultivation'. In carrying out their recommendations he ran into agrarian troubles already rampant in three of his Western forests — Gillingham in Dorset, Braydon in Wiltshire, and the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire.

In Gillingham lands had been granted to Sir James Fullerton and George Kirk, two of Charles's Scottish friends and Gentlemen of his Bedchamber. They were given licence to depark and proceeded to enclose and farm. But the forest dwellers, on the grounds that their ancient rights of common were being violated, pulled down the fences as fast as they went up. Messengers from the Privy Council were whipped and their orders burnt while soldiers in the neighbourhood rescued the few rioters who had been apprehended. In November 1638 the High Sheriff of Dorset brought in more troops but found 'a great and well armed number' of rioters holding their position under the slogan 'here we were born and here we stay'. Some eighty of them were fined by the Star Chamber, but a couple of years later the struggle was still continuing under a leader styled 'the Colonel'.

In the Forest of Braydon Charles was more closely concerned, for here he was attempting to enclose and farm himself. Commissioners whom he sent down to smooth the way were told that enclosure would spell the 'utter undoinge' of many thousands of poor people by depriving them of rights of common and other perquisites. Fences were no sooner up than they were torn down. The local people were very much at one, even the larger landlords sharing the claim to what

were looked upon as customary rights. Privy Council messengers were beaten up and were powerless to stem the destruction of fences and ditches or to silence the 'jeering and unbecoming speeches of the rioters'. Only by means of informers were some of the leaders apprehended. But Charles had no taste for this kind of struggle, and he granted large areas of the Forest of Braydon to freeholders and other tenants, while continuing merely a modicum of farming himself.[12]

The Forest of Dean presented an even more complicated picture, for here was a way of life that for three hundred years had suffered no external interference. The forest proper was in poor condition through lack of care, indiscriminate felling and failure to replace; in rough forest clearings, which often stretched for miles, small-scale agriculture and common land were interspersed with coal and iron-mining, with charcoal burning, with tanning and other small enterprises that depended upon bark or other forest products. Monarchs had long since abandoned the Dean as a hunting ground and its inhabitants responded to little law but their own. If Charles were to farm or to use the timber resources of the Forest systematically he would be stirring up dozens of vested interests. Under a leader called Captain Skimmington the inhabitants of Dean made it clear that they would tolerate no interference. They were in touch with the protesters in Gillingham and Braydon and, again, Charles was not prepared to force an issue. He got even less from his attempts to farm his forest lands than he did out of his forest fines.

More rewarding were the Crown lands proper. Sir Julius Caesar had judged them 'the surest and best livelihood of the Crown', in spite of the heavy sales of Elizabeth and of James which had much reduced their annual value, from around £111,000 in 1608 to less than £84,000 in 1619. Although he himself had been compelled to part with Crown lands to settle some of his debts, Charles succeeded, by careful management, in reversing the trend. Entry fines on new leases were raised; rents were increased, though they were still mostly lower than elsewhere; in cases where entry fines were fixed the tenants were sometimes persuaded to buy their freeholds at from twenty to fifty years purchase. His woods and coppices were surveyed, the timber trees numbered and valued and, where appropriate, were sold; new plantings were made and, where possible, enclosure protected the young growth. Charles noted the consumption of wood by iron works, and to reform 'the great waste of timber' appointed a Surveyor of Iron Works to exact fees in proportion to timber consumption. Judges of

Assize were instructed to implement existing laws governing the preservation of forests. But the Crown lands were scattered, frequently uneconomic in themselves, their administration was too often weak, costly and venal. Although Charles did succeed in raising his income from them, his careful work brought in not more than £10,000 a year from woodlands and £80,000 from the rest. A compact area of land, such as Salisbury's Great Contract had envisaged, would have served him better.

As a further result of the Report of the Commission on the raising of Money, John Borough, Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London, was instructed in January 1628 to search through his documents for precedents relating to another issue. His findings resulted in the appointment of a commission two years later 'to compound with persons who, being possessed of £40 per annum in lands or rents, had not taken upon them the order of knighthood'. And so knighthood fines came into being. It had been customary for every person of a certain standing to come forward at a king's coronation to receive the honour of knighthood but, as feudalism decayed, so had this practice, and for over a hundred years it had been in abeyance. Charles now declared that he would revive the practice and fine those who had not been knighted. The actual fine, assessed by local officials in accordance with a man's ability to pay, generally amounted to a sum between £10 and £100 and on average to about £17 ot £18 a person. Between 1630 and 1635 the 'business of no-knights' brought Charles about £180,000 in knighthood fines. There was little opposition, the levy was accepted as reasonable, and the individual sums were not large.

Forest fines and distraint of knighhood both arose from Charles's position as feudal overlord. A third form of revenue deriving from the same source was the most anachronistic of all. The rights of wardship depended upon the fact that many landowners still held their land, theoretically, on feudal tenure from the King by Knight service, and that he could exercise the feudal right of taking charge of their heirs who succeeded while under age. The Crown could administer the lands of these minors, supervise their upbringing and education and plan their marriages, through the Court of Wards. Idiots and lunatics of any age who inherited such lands came within the scope of the court; the re-marriage of widows who had been wards of court remained its concern. Though wardship originally comprised an element of protection to the minor, by the seventeenth century the Court of Wards had become a court of profit so brazen that wardships were

6

James I by an unknown artist, probably

shortly after his accession to the English throne.

7

Queen Anne, by William Larkin, 1612. The

Queen is in mourning still after the death of Henry.

8

Charles's sister, Elizabeth, as he knew her, from a

miniature painted about 1610 by Isaac Oliver.

9

Charles, as painted by Daniel Mytens, after

his return from Spain, probably in 1623. There

is diffidence still in his stance though his legs

are undoubtedly straight and do not look

noticeably short.

10

The Duke of Buckingham, also painted

by Mytens at about the same time. In

contrast to Charles his whole bearing

portrays confidence and command.

11

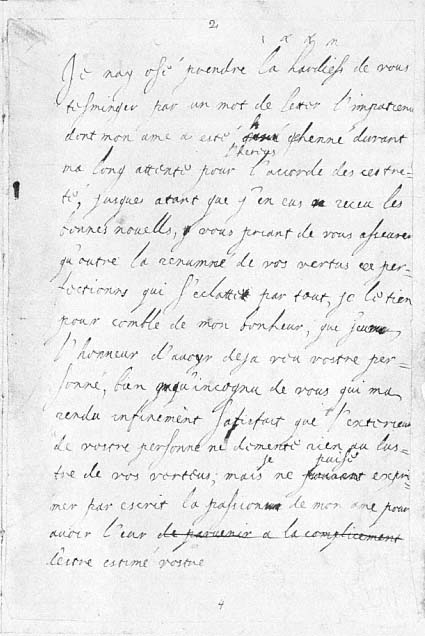

A page from a draft of Charles's earliest love letter to Henrietta-Maria, whom he

has not yet seen. His indecision and diffidence is still apparent in the many erasions

and, indeed, in the fact that he made a draft at all.

12

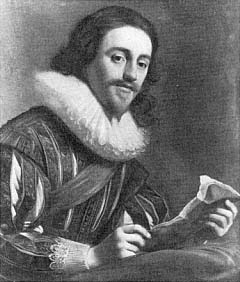

At the end of the 1620s, Charles passed into

the happiest period of his life. This portrait by

Gerrit van Honthorst, painted informally from life

towards the end of 1628 as a study for the great

canvas of Apollo and Diana , shows Charles as

a relaxed and happy man.

13

This unusual and informal representation of Charles at cards, at about the

same time, by an unknown artist of the studio of Rubens, is undoubtedly

based on descriptions by the master of the life he experienced at the English

Court. Charles's enthusiasm for card games is well attested.

openly sold, leases of wards' properties put up to the highest bidder, wards' marriages not only arranged but bargained for. Charles used his opportunities to the full. Whereas between 1617 and 1622 the net revenue from wardship had been just under £30,000 a year, between 1638 and 1641 it averaged close on £69,000 annually. As with other sources of revenue the mastership of the Court of Wards was not normally in royal hands but was leased for a fee: Salisbury had done very well as Master, Cranfield had held the post, Sir Robert Naunton held it from 1623 to 1635 when he was succeeded by Cottington.

Allied with wardship was livery, which derived from the King's feudal right to approve the succession of those who held lands direct from him and was now exercised in the form of a tax or fine of succession. Altogether sufficient vestigial feudal practices survived to make an appreciable contribution to the King's income. The reverse of the coin was that they also operated as a tax upon the King's landed subjects. Forest fines and Knighthood fees were once-for-all payments. Wardship and livery were the more pernicious in being continuous. Whatever Charles gained from any of them, it was not difficult to surmise that he would have to pay the price in some form of concerted opposition to his policy.

20—

The King's Great Business

Charles's mind was meanwhile reaching out to other aspects of sovereignty: overlordship of the land would be matched by dominion of the seas. His passion for ships and for the sea had never flagged, and he was well aware of the contribution that fishing could make to the navy and to national prosperity. Fishing fleets were the nursery of sailors; fishing provided employment for thousands; the fish themselves enhanced his trade and fed his people; the herrings that swam in the seas round his shores seemed as native to Britain as the sheep that grazed her pastures. The fishing off the Newfoundland coasts, the deep-sea fishing and whaling in the Northern seas, were additional assets. But while English fishermen might have a virtual monopoly in more distant waters, the Dutch were pressing strongly in the North Sea and round the home shores, even in the Channel and off the coast of Yarmouth where the herring shoals were thickest.

The Dutch had been fishermen for centuries and even laid claim to the invention of herring curing, which they attributed to a thirteenth-century inhabitant of Vierveldt. Permission to fish in waters which the English claimed as their own had been conceded in return for the purchase of licences and the acknowledgment of England's claim to sovereignty of the seas. But in 1609 the Dutch made a counter-claim to freedom of the seas in the Mare Liberum of Hugo Grotius, on the strength of which Dutch fishermen became more audacious. They evaded payment of licence, their armed escorts became more obtrusive, at rendezvous in Shetland they could muster 26,000 herring busses and they brought armed ships with them for protection — ostensibly against pirates. They made free of English ports, spreading their nets upon the strand, victualling their ships from English towns. Yarmouth, it was reported, employed forty brewers in their service.

The reply to Mare Liberum was Mare Clausum , written by John Selden in 1619 on James's instructions. Selden admitted that the extent of British sovereignty had never been clearly defined, but he claimed roughly the whole of the North Sea, the English Channel, the Bay of Biscay as far south as the coast of Spain, and indefinite stretches of ocean north and westward. The situation had not materially changed when Sir Robert Heath in 1632 was jotting down his thoughts on the subject: 'our strength and safety lies in our walls, which is our shipping . . . we should maintain the King's prerogative of fishing round our coasts and secure his mastery of the Narrow Seas.' Charles had been thinking along similar lines. There seemed no reason why such a natural bounty as fish should not, if properly managed, be a pillar of national prosperity, a nursery for the navy, and a source of revenue to the Crown.

For the protection of the fish themselves repeated proclamation prohibited the use of the trawls that were destroying the small fry. To encourage demand Fish Days and Fast Days were enforced. Charles himself was much concerned in the deliberations of a Commission he appointed in 1630 to study the matter, and he amended extensively in his own hand the draft proposals which Secretary Coke drew up. These resulted in 1632 in the incorporation of the Society of the Fishery of Great Britain and Ireland whose purpose was to encourage and maintain fishing fleets round the English, Irish and Scottish coasts. A large curing and packing station for herrings was established on the Isle of Lewis and Charles insisted upon including into the scheme any 'poor fishermen' whose normal livelihood would be jeopardised. He expected to make an annual profit of £200,000 from the enterprise. But, although the Lord Treasurer himself took shares in the Society, and powerful Privy Counsellors like Arundel and Pembroke were among its members, it lasted no more than two years. The herrings, it was said, 'failed to come'. In fact this was not the full story. Herrings, like salmon, travel a well-defined path and the lochs of the Isle of Lewis were an occasional rather than a regular haunt. Land had been bought without due consideration, the curing sheds, the storage huts, the houses for workpeople had been built too soon on too large a scale, supplies had been ordered prematurely in excess of what could be required. Money and labour had been expended unskilfully and wastefully, if not fraudulently. Employees of the Society were deliberately misled by uncooperative natives whose chief object was to see them depart, they were harrassed by Dunkirk pirates.

Above all, they built boats unsuitable to the herring fishing and failed to learn either from the efficient Dutch herring busses or from their own more experienced fishermen. It was one more example of good intention warped by faulty execution.[1]

Charles had been deeply involved, and the failure of the Fishery Society was a great disappointment, particularly since England's position as mistress of the seas was becoming more precarious. There were clashes with the Dutch in the East Indies, where the Dutch East India Company was challenging the British, the Dutch were becoming troublesome in the New World, where their fishing vessels were competing with the English and where they were attempting settlement on the mainland. Nearer home Jerome Weston was returning from an embassy in France in the spring of 1633 on the Bonaventure when he fell in with eight Dutch merchantmen in the Channel. The English captain required the Dutch to lower their topsails as the normal mark of respect. When they refused, his answer was to fire a couple of shots at them, upon which they responded with their own guns. The English, outnumbered by eight to one, left the honours to the Dutch. As such incidents multiplied neither the Dutch nor even the Spanish paid much respect to English sovereignty, chasing each other with impunity into English harbours, abusing to excess Charles's patience, as the Venetian Ambassador put it. Charles was particularly annoyed when a Dutch ship seized an English barque carrying a courier with letters for the Venetian. He was angry when in March 1635 Dunkirkers captured and retained as prize a ship carrying tobacco to Holland. He never forgot that when his wife was pregnant in 1630 her midwife had been captured by Dunkirkers in the Channel. He read with bitterness Secretary Coke's report in June 1634 telling of the 'scant respect' shown to the English in various parts of the world: 'Our ancient reputation is not only cried down, but we submit to wrongs in all places which are not to be endured'.[2]