Chapter Two

The Artists

The entire Fourteenth Street group was motivated by an interest in the picturesque, in spectacle, in action, and in local color. If there was criticism, it was only by implication. On the whole, they were more interested in the excitement of urban life.

MILTON W. BROWN , 1955

The problem of writing an artist's biography lies at the heart of Alison Lurie's 1988 novel The Truth about Lorin Jones . Polly Alter, an art historian and feminist employed by a New York museum, has recently mounted her first exhibition, Three American Women. The show generates such a strong critical and financial interest in the overlooked work of one of these women, Lorin Jones, that Polly receives a grant to write her biography. The story Polly determines to tell, based on her initial research into Lorin's life for the exhibition, is that of a shy, fragile woman, manipulated by men, even driven toward the self-destructive behavior that caused her early death. Lorin's husband, an older and highly esteemed art critic, had kept her from contact with the art world; her cagey dealer, who believed there was no such thing as a great woman artist, had barred her from the decision-making process in the exhibition of her work; her reckless young lover, an irresponsible poet, had run with her to Key West, then abandoned her in the days of her final illness. Polly, encouraged by a circle of supportive feminist friends, will breathe new life into her beautiful and gifted subject, transforming her from victim to heroine.

When she finishes her research, much of which consists of interviews with Lorin's relatives, friends, and associates, Polly is confused and feels "her subject splitting into multiple, discontinuous identities."[1] Polly also realizes that the shape of her account will determine her own future; to write the book from the perspective of Lorin's dealer and former husband (portraying Lorin as a "neurotic genius") would mean presenting them in a generous light. This approach would guarantee the book good reviews and assure her acceptance in established (male) art circles. To follow her original plan would gain her the praise of feminist critics but harm the professional connections she had already cultivated.

Polly comes to understand (though not in these terms) that along with Lorin, each of her informants is a divided, inconsistent classed and gendered subject with a correspondingly different take on Lorin's life, and on one another. Beyond the consensus that Lorin was beautiful and talented, Polly finds little agreement. If all informants tell the truth, there is no one truth about Lorin Jones; there are only various stories. Polly also senses the shifts in her own version of Lorin. Different Lorins emerge not just with the imposition of other views but with her changing reactions to events in her own life and their parallels or divergences from those of Lorin's life. Her own identity and Lorin's are "subjectivities in process."

Faced with portraying Lorin Jones as either "innocent victim" or "neurotic unfaithful, ungrateful genius," Polly rejects both choices as "all lies" and decides to tell instead "the whole confusing contradictory truth," even if it means producing a narrative that will be "unfocused" and "inconsistent."[2] Though Polly realizes that Lorin's life has moved through a number of contradictory subject positions, represented in part by the narratives of her informants, she still believes that she can arrive, through multiplicity, at something like the truth. In fact, Polly will add yet another, perhaps fuller, account to the chain of stories (texts), but it too will become the subject of another interpretation.

Although I have not confronted the extreme contradictions of this fictional narrative, I use Polly's dilemma to problematize my own "biographical" account of four contradictory subjects. I discuss the four artists individually and in relation to one another—chronicling the "road to Fourteenth Street," where they found the common subject matter that gave them their name. I want to show how their lives, beliefs, and activities were bound up in a process of social change; personal artistic development cannot exist outside of historical processes, institutions, or ideologies. Although all the artists shared subjects and a commitment to painting the contemporary scene by drawing on the art of the past, each pursued that commitment from within a particular constellation of experiences, some shared, some not. They arrived at Fourteenth Street via different paths; differences of generation, class, gender, social life, education, and politics make for different patterns of interaction in their lives and art. Miller, a generation older than the other three artists, was a close friend and teacher of Marsh's and Bishop's. Soyer was a Russian Jewish immigrant whereas the other three were native-born and middle to upper-middle class. Bishop worked as a woman artist among the men. In the early thirties, Soyer joined the Communist John Reed Club while Miller, the most politically conservative of the group, found fault with leftist activities; Bishop and Marsh could be characterized as New Deal liberals, though neither became a political activist during the Depression.

The problem of individual versus group identity looms large, especially since the designation Fourteenth Street School was initially general and fundamentally ahistorical. Coined by John Baur in 1951, during the early days of the New York school

and formalist criticism, the name referred to certain formal categories of style. Baur described the Fourteenth Street School artists as romantic realists working in either a hard or a soft manner. They rediscovered "the poetry of the city and its poor," thereby continuing the revolution in subject matter initiated a generation earlier by the Ashcan school realists.[3] Though Milton Brown's brief 1955 analysis looks at how the group's training and influence make them a "school," "Fourteenth Street realism" remains a general term describing the urban version of American Scene painting and its best-known practitioners.[4] I retain the name here because it is familiar and convenient and because it designates a historically specific and symbolic social environment in which women imaged by these artists became major players.[5]

A second problem of group biography has to do with unequal evidence and its relation to artistic production. Accounts of individual artists cannot treat their lives and work as parallel; large bodies of archival material offer valuable insights but also leave large lacunae, as do monographs and exhibition catalogs. Critical response, depending on the fate of each artist's reputation, has been quantitatively as well as qualitatively mixed. Gallery records exist for Bishop and Marsh in the 1930s but are more difficult to locate for Soyer. Miller left a large personal correspondence in which he records what he read and discusses his artistic philosophy, but he destroyed much of his early work. Marsh obsessively documented his comings and goings and his working habits in daily diaries. Biographers, though reticent about his personal life, have often focused on his personality and the psychological motivations underlying his art. Miller and Marsh died in the early fifties, when the interest in 1930s realism was at a standstill and before the recording of oral histories became a standard research technique. Like Miller, Bishop destroyed much of her early work (though some photographic records remain), but she talked at length about her art and her experiences as a female artist in interviews, especially after her first retrospective exhibition in 1974. Soyer destroyed his diaries from the 1930s and showed his works at several galleries, none of which kept records that survive. With the renewed interest in realism and the relation between art and politics in the seventies, Soyer, like Bishop, has been the subject of many interviews, including my own. He has also written four accounts of his travels and experiences, including that of being an artist.

A third problem (the one most closely related to Polly's dilemma) has to do with the "teller of the tale" and the uses to which the evidence is put. In accounts of their own work (statements about intention), artists determine how the work will be seen and read and how their lives will be understood—they create themselves. Such texts—whether personal interviews, autobiographical narratives, or biographies—are produced under different conditions, function according to their own conventions, and should be understood as both evidence and interpretation. As such they need to be historicized and weighed alongside other accounts rather than

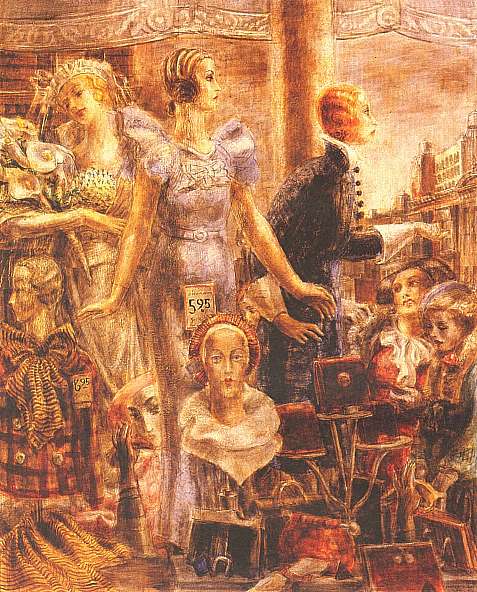

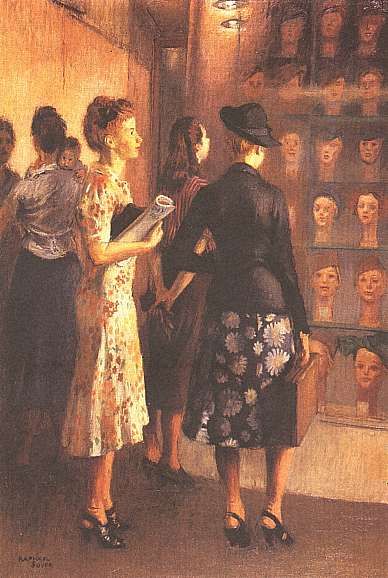

privileged as the most accurate statement of the work's meaning. The four members of the group spoke in different ways about their intentions: Miller believed that form was more important than subject, Marsh wanted to re-create the grand manner in his art, Bishop was concerned with the aesthetic problem of how to create movement, and Soyer claimed that he only painted what he saw and tried to make a picturesque arrangement. Many of their statements focused on the making of art or on the need to belong to part of a larger artistic tradition. Although all acknowledged the need to make contemporary life their primary subject, they rarely spoke about their attitudes toward shopping or working women in the Depression.

Artists' statements (and the concerns of their interrogators) may change over time to reflect a shift in critical interest (their own or that of a period) or a change in the market for their work. When I first interviewed Raphael Soyer, for example, his replies to my questions were almost verbatim transcriptions of his earlier writings in which he told anecdotes about his life and work that expressed his artistic values and his vision of the artist's social role. By the early eighties, however, Soyer was enlarging earlier accounts of the Depression to include a nostalgic invocation of the art world of the 1930s. In particular, he cited the struggles for political freedom (the fight against Fascism) and social betterment among an egalitarian community of artists. His understated critique of "blue chips in art" and artists as "celebrities" in the early eighties needs to be seen as part of a larger challenge by intellectuals on the Left to the values of the art world and the effects of Reaganomics.[6]

Biographers' narrative styles, artistic values, and subject positions can resemble or differ radically from those of the artists they discuss. Lloyd Goodrich, for example, who wrote monographs on Miller, Marsh, and Soyer, was Marsh's closest childhood friend. He studied with and wrote the first extended account of Miller, in 1930, and produced a substantial volume on Soyer in 1972. Goodrich followed a chronological model of development from the artists' youth to maturity. Based on his own frequent interactions with his subjects, his descriptive accounts deal with the artists' processes and concern themselves with artistic motivations and intentions. Although he was willing to discuss their general psychological makeup when I interviewed him, Goodrich was exceptionally discreet about their personal lives.[7]

To avoid a reductive biographical analysis of the works as direct transcriptions of individual artists' experiences, I emphasize the social and historical circumstances of making and viewing art, an approach that revises conventional critical assumptions of the artist as solitary creator. Each of the four artists was a historically located producer, painting in a New York City studio on Fourteenth Street according to the general dictates of American Scene painting and figurative composition in the twenties and thirties. Each worked through and was supported by an emerging network of art institutions in the interwar decades—galleries, museums, art

schools, and social or political organizations supported them even as their works affirmed the artistic values of those institutions that sought to reconcile modernity and tradition. Moreover, a critical discourse explained, and continues to explain, how they worked and how their pictures are to be read. Finally, the four artists of the Fourteenth Street School were very much part of the world in which the discourses on new womanhood took shape. Whether in their personal lives or friendships, in their intellectual preoccupations, or in their artistic surroundings, they experienced the social changes and the social conflict brought about by changing gender roles and shifting notions of class. Such changes involved families, the world of work, and the institutions that helped to form their painting practices, not to mention the entire range of determining structures outside the artists' control. The artists (to quote Griselda Pollock) are themselves subjects "articulated through the visual and literary codes of [their] culture and inscribing across them both [their] particular history and the larger social patterns of which all subjects are an effect."[8]

In the four accounts that follow, I will touch on individual lives and social interactions that illuminate the artists' representations of new womanhood, considering the bearing of these elements on the meaning of the paintings in individual chapters on female types. The artists came to negotiate a middle ground in both their personal lives and artistic strategies by the late 1920s, when all began to paint the contemporary scene. To varying degrees they embraced the social changes of their time, but most did so without radically altering established gender roles.

Kenneth Hayes Miller

Although Kenneth Hayes Miller was the most conservative in social and political outlook of the four artists I discuss, he spent his childhood in an environment that challenged many of the social and sexual underpinnings of Victorian America. Miller was born in 1876 to Annie Elizabeth Kelly and George Miller, who lived in the Oneida community, one of the more successful and long-lived of the nineteenth-century utopian experiments (1848-1879). Within the settlement, founded by John Humphrey Noyes (Miller's granduncle by marriage),[9] Oneidans, like the Shakers and the Mormons, combined a religious quest for spiritual perfection with a desire to alter monogamy and the nuclear family.[10] They did so, as Louis Kern has explained, through communal sexuality, complex marriage, and a eugenic experiment called stirpiculture. To separate the joyous amative component from the unwanted propagative result of sexual intercourse, Oneidan males, counseled by their leader Noyes, developed a system of male continence by which the male completely withheld ejaculation, permitting his female partner orgasm without fear of conception. This system of coitus reservatus was a version of the nineteenth-century spermatic economy doctrine, which held that the loss of seminal fluid would debil-

itate male vitality, in its most extreme form causing complete mental and physical deterioration. Whereas the usual solution was abstinence, the system of male continence permitted frequent sexual encounters in a community where free love (understood not as promiscuity but as a belief that love rather than marriage should determine sexual relations) was both central and sacred. It also allowed the male to develop and subsequently practice an extreme form of sexual self-control that demonstrated male perfection.[11]

Behind the system of complex marriage lay the assumption that the most unselfish love was one that subordinated individual desire and romantic feeling to the communal good. Hence, all men and women in the community were married to one another. Men could request sex from any woman in the settlement, and although a woman could refuse, she was not permitted to initiate any such encounter. Sexual pairings came under community surveillance, which took the form of regular mutual-criticism sessions. In 1867, as the ranks of single or widowed women grew and as the system of male continence proved an effective method of birth control, Oneidans instituted the eugenic experiment known as stirpiculture. Community leaders (principally Noyes himself) either selected or approved couples for childbearing.[12] The healthiest women mated with men who best exemplified perfectionist ideals to produce offspring who would improve the race or, at a more mundane level, fill a need within the community. It is said, for example, that Miller's parents were designated to produce a badly needed carpenter.[13]

George Miller and Annie Kelly, like many second-generation Oneidans, grew dissatisfied with complex marriage; couples designated for reproduction often forged romantic attachments. Community efforts to rechannel these bonds and to negate maternal connections by placing children in communal nurseries met with increasing resistance both inside and outside the community. In 1879 these pressures sent Noyes into exile near Niagara Falls; community members who moved to the Oneida suburb of Kenwood restored monogamous marriage among themselves. Miller's parents, who married and had another child, Violet, in 1882, followed Noyes and spent several years in the Niagara settlement before returning to Kenwood. George Miller worked for the various business ventures attached to the community, the most successful of which was Oneida Silver. During his son's adolescence, he managed the silver company's New York office. Kenneth attended the Horace Mann School, and in the 1890s took classes at the Art Students League, where he studied with the academic artists Kenyon Cox and H. Siddons Mowbray. Until World War I he maintained close ties with Kenwood, corresponding regularly with a cousin and friend and visiting his mother there during the summer. Miller established his residence in New York, where his attempts to earn a livelihood as an illustrator proved unsuccessful. He began earning a steady income as an art teacher, first at William Merritt Chase's New York School for Art (from 1899 until 1911, when it closed) and then at the Art Students League.[14] Miller's first wife, Irma

Ferry—whom he married in 1898—came from Kenwood, although she had never been part of the original community. She and Miller divorced in 1911, and Miller married Helen Pendleton,[*] a young art student with whom he had an apparently happy, if not always monogamous, marriage.[15]

Despite the radicalism of the Oneidans' separation of reproductive demands from the pleasure of sex, the community's social and sexual ideologies continued to reflect both the sexual tensions and the patriarchal structures of late nineteenth-century bourgeois society. Louis Kern shows how community practice was designed to effect social order. Women in the settlement received respect without any accompanying alterations in material circumstances or roles. They held positions of authority in community kitchens and nurseries, and although they attended mutual-criticism sessions, male leaders made all policy decisions. Oneida doctrine held that women were in need of control. In contrast to the Victorian cult of true womanhood, which granted women moral superiority for chastening the sexually uncontrolled male, the Oneidan philosophy reversed the charge. Women were selfish and sexually licentious; their nature was grounded in base physicality. Male love was noble and unselfish. Male continence, a demonstration of greater self-control, not only signified male superiority but also protected the spiritual male from entrapment by female sexuality. In this ideology women became objectified goods, controlled by the male, who maintained his power over them by reserving his semen.[16]

Conditioned by a biblical claim that man was above woman in all things and by a notion of biological difference that prescribed separate roles for men and women, most Oneida women accepted the doctrine of male superiority. Their rebellion in the late 1870s was shaped less by a demand for equal rights than by a desire to return to traditional monogamy and a family organization rooted in the ideology of separate spheres. This assertion of women's natural superiority within the family, conjoined with a belief in women's natural submissiveness and duty, challenged the values of Oneida and eventually undermined the all-encompassing yet precarious structures of social control.[17]

Over the years Miller's intellectual response to the Oneida ideology was part rejection, part accommodation. The artist's belief in certain Oneidan ideals was not simply an extension of Oneidan values but the integration of Oneida's principles of sexual radicalism (and its attendant conflicts) into a particular segment of the larger New York intellectual milieu. Throughout the teens Miller lived near Green-

* Although I refer to all four artists by their surnames, when I discuss the male artists with their wives, all of whom took their husbands' names, I have sacrificed absolute consistency, attempting to balance one preference, for an egalitarian practice (i.e. Kenneth Hayes Miller and Helen Pendleton Miller), with another, for a straightforward style (i.e. Kenneth and Helen Miller). In a few instances I retain a male artist's surname alongside his wife's first name (i.e. Miller and Helen). While this may not be fully satisfying, it avoids making the marriage sound like a law practice (i.e. Miller and Miller).

wich Village, where many of the most radical new woman gathered, in company with male writers, social reformers, and literary figures, to articulate new forms of feminism, modern love, and socialism. One component of their sexual discourse focused on separating reproductive concerns from sexual pleasure—also a central concern in the Oneida community. At the same time, however, writers began to express what Ellen Kay Trimberger has defined as the desire "to combine mutual sexual fulfillment with interpersonal intimacy."[18] Under the influence of the European writers Edward Carpenter and Ellen Key (an advocate of shared passion and friendship whose Love and Marriage Miller read avidly), Village intellectuals challenged the ideal of separate spheres. Where nineteenth-century feminists wanted to create more equal marriages by deemphasizing passion (and hence reproduction), thereby freeing women to enter the public sphere, their twentieth-century Village counterparts campaigned for birth control and advocated a psychological and sexual intimacy that would make men and women fully equal. Women would share men's public roles while males would share the domestic sphere.[19]

In its most radical formulation this ideal of psychological and sexual intimacy and equality was short-lived, its fullest articulation, acceptance, and practice limited to the teens. By the 1920s it had become generalized as the middle-class ideal of companionate marriage. The intellectuals, many of them male, who continued to support the notion of sexual intimacy did so now in the context of marriage and family rather than a love relationship. Furthermore, in the less politically progressive climate of the postwar years a greater level of intimacy became possible as women refocused their energies, empathizing with men from the domestic sphere. The companionate ideal accommodated sexual intimacy without recognizing ideals of equality.[20]

Like other middle-class intellectuals of his generation who had migrated to New York, Miller experimented with social and political radicalism in the teens. In 1916 he voted for the Socialist candidate Eugene Debs and marched with his suffragist wife Helen for "votes for women." His circle of literary acquaintances included Theodore Dreiser, a close friend whose social realist novels were singled out by Randolph Bourne in his New Republic book reviews for their direct and honest treatment of American life and sexual mores. Miller admired Van Wyck Brooks, Sherwood Anderson, and the literary and music critic Paul Rosenfeld, an avowed cultural nationalist, who proclaimed Miller an important modern American painter—along with Albert Ryder, Marsden Hartley, Georgia O'Keeffe, Arthur Dove, and Alfred Stieglitz—in his 1924 publication Port of New York . Though Miller never mentions meeting Max Eastman, the artist was particularly interested in his literary criticism; Eastman was the editor of the radical New Masses whose political activism included his organizing a men's committee to support suffrage. Finally, during this period Miller embarked on a systematic study of the works of Freud. Although he wanted principally to understand the relation between the

unconscious and creativity, he also professed an interest in Freud's insights into femininity and human sexuality.[21]

Miller's activities and interests also conformed to a generational pattern: short-lived political radicalism succeeded by conservatism in the twenties and thirties. Furthermore, his marriage made conventional demands on his wife while permitting him both greater independence and control. Miller supported the family primarily through teaching at the Art Students League. Although Helen Miller was also a practicing artist, she assumed all traditional familial duties, especially following the birth of their only daughter, Louise, in 1914. Throughout the teens, Miller and Helen seemed to have a close and intellectually stimulating relationship; they read literature to one another in the evenings, went out with friends, and became deeply interested in Freudian psychology.[22] When Miller moved to his Fourteenth Street studio in 1923, the dynamics of the marriage changed. Armed with a new knowledge of Freud, the Millers evolved a more open, though still committed, relationship. During the week, Helen and Louise remained at the family home a short distance from the studio, where Miller lived during the week, returning home on the weekends. Around this time, Miller began a succession of liaisons with female art students. Helen and the current mistress presided over the weekly Wednesday afternoon teas Miller held in his studio for more than a decade.[23]

Students and close friends who came to the teas have noted contradictions in Miller's personality and behavior. He was by many accounts a stern and exacting teacher, who imparted a wealth of knowledge to students but exerted a strong control over their production. Most considered him a deliberate and disciplined (if not talented) artist. They described his approach to painting and to life as intellectual and ascetic; one student called him an "uptight New Englander"—a reference, perhaps, to the Oneida ideal of male self-control.[24] Alexander Brook, another student, once told Raphael Soyer, "When Miller is finished criticizing a painting of yours, you feel like pushing your foot through it."[25] He was also described as sensitive and vulnerable to criticism—and as a man who possessed a deeply romantic and sensuous side.[26]

Throughout the twenties and thirties, Miller continued to express great affection for Helen and Louise in notes penned from his studio.[27] His correspondence with his mother—herself a fiercely independent yet loving woman—conveyed the devotion of a dutiful son. Although Miller's sexual behavior typified that of urban intellectuals in the teens and 1920s, his letters reveal that he continued to hold deeply conventional attitudes about women's separate roles. On more than one occasion, for example, Miller professed his inability to care for himself without Helen's nurturing skills. He often told his mother that Helen would have to explain Louise's progress since he had been too preoccupied with work to notice. At Christmas in 1915 he wrote, "I know you are hungry for news of Louise, what new words she has learned and new ways. I can't recall. Helen will not fail you in these topics I

am sure."[28] Clearly he considered Helen's maternal responsibilities more significant than his paternal ones, more a part of her natural sphere of activity. Miller expressed great admiration for Helen's painting and accepted a woman's need to have outside interests. "Helen wants to get into some kind of practical work as Louise gets older," Miller wrote to his cousin Rhoda Dunn. "The business of being merely a wife and mother is too deadening for always."[29] By "practical" he seems to have meant the feminized occupation of clerical work; several years later he expressed delight with Helen's progress in typing. In spite of Miller's concessions to modern womanhood, however, their companionate marriage centered around his own activities as teacher and artist, their emotional life around his needs, which he controlled. Helen's role was that of wife and mother first and artist last.[30]

Miller's social and sexual behavior must be interpreted in light of his experiences both in the Oneida community and in Greenwich Village during the teens and twenties. He accepted the greater sexual freedom espoused in both communities, and he believed in human perfectionism and in male superiority as the means to social control. At the same time, his parents' accounts of Oneida's repressive measures made him suspicious of certain forms of radical social and political change. Studio liaisons notwithstanding, he clung to the ideal of companionate marriage. Then in the early 1930s, when he was close to sixty and when many younger artists joined the political Left, Miller expressed his deep reservations about all revolutionary activities. He rejected his own experience of what he called communism (Oneidan communism had aspirations very different from those of the intellectual Left of the thirties), arguing that individual rather than communal values must remain at the heart of the American political system.[31]

Reginald Marsh

Some of Miller's values would be passed along to one of his more admiring protégés, Reginald Marsh. Although Marsh also came to Greenwich Village in the early 1920s, he arrived via a route different from Miller's. Furthermore, he experienced New York and the Village through the eyes of a postwar generation of youthful artists and writers, not, like Miller, as a member of a generation that came of age in the 1890s, participated in the Armory Show, and advocated suffrage. Miller came from a solidly middle-class background; Marsh's inherited wealth, upper-middle-class background, education, and marriage gave him ready access to the established art world.

Marsh's early biography resembles the romantic narrative of the artist-to-be. He was born in Paris in 1898 over the Café du Dôme, a well-known gathering place for artists. As a small child he was sickly and passed quiet hours reading and sketching. Both parents were artists, supported by income inherited from Marsh's paternal grandfather, who had made a fortune in the Chicago stockyards. Marsh's father,

Fred Dana Marsh, exhibited at the Paris Salon and made his reputation painting portraits in the then popular style of John Singer Sargent. In 1902, when he was only thirty-one, the National Academy of Design elected Fred Marsh an associate member. He went on to execute several mural commissions and finally painted men working on the construction of New York's early skyscrapers.[32] Lloyd Goodrich, Marsh's early biographer and childhood friend, characterized Fred Marsh as a man of too many talents who never realized his potential as a painter. Disillusioned with his career, he turned to amateur inventing and architectural projects. And he discouraged his son from becoming a professional artist.[33] By contrast, Marsh's mother, Alice Randall, enthusiastically supported her son's career choice. Alice had received her training from the academic artist Frank Vincent DuMond in the early 1890s and went on to become a painter of miniatures.

The Marsh family returned to America when Reginald was about four and settled in Nutley, New Jersey, then populated by many artists and writers. Marsh's childhood and adolescence were typical for his social class and background, with private schools and summer vacations in the fashionable seaside retreat at Sakonnet, Rhode Island. Marsh spent his junior year of high school at Riverview Military Academy in Poughkeepsie, New York, followed by senior year at the prestigious Lawrenceville Preparatory School. In the fall of 1916 he entered Yale University, where he decided to major in art.[34]

Yale educated him in the tradition of high European culture—literary classics and, in art, the Renaissance masters. Studio training at the university remained fully academic,[35] but Marsh found a release from the regimentation in illustrating a variety of popular subjects for the Yale Record , a humor magazine. Campus colleagues appreciated his depictions of muscle men, locomotives, pretty girls, and Yale social events so much that by his senior year the editor of the Record , William Benton, took the unprecedented step of paying Marsh fifty dollars per month for drawings to be used in the magazine after Marsh's graduation. Finally, university life also introduced Marsh to the fast-paced life of contemporary privileged youth he would pursue further in Greenwich Village. He took part in all the pleasures—alcohol, girls, and dancing parties—of American social customs and gender relations in the postwar world.

Marsh arrived in New York with his sights initially set on newspaper and magazine illustration rather than painting. In a short time he established himself as a free-lance illustrator, accepting assignments that gave him much of his subsequent New York subject matter and working for publications targeted to vastly different audiences. From 1922 to 1925, the popular new tabloid the Daily News employed Marsh to sketch and write critiques for their vaudeville column. Frank Crowninshield from the high-style magazine Vanity Fair sent Marsh on his first of many trips to Coney Island. For the new New Yorker , Marsh drew sketches to illustrate theater and film reviews and created portraits of well-known figures for the magazine's Profile section. He also entered the world of theater as a set designer; in 1923

he worked with Robert Edmond Jones of the Provincetown Playhouse on sets for a revival of the play Fashion; or, Life in New York . Even when Marsh took up painting, he continued to illustrate, working for periodicals as varied as Fortune and Life and, for a short period in the early 1930s, for the radical publication, the New Masses .

Marsh developed his attachment to Greenwich Village bohemia during the early twenties, as the prewar generation gave way to the postwar generation. Although he numbered some of America's foremost realist writers among his friends and acquaintances—among them John Dos Passos and Theodore Dreiser—Marsh arrived just after the most radical women's rights activity, labor unrest, anti-war activism, and artistic experimentation had either subsided or taken a more moderate course. Many progressive writers and artists associated with The Masses had left the Village for Europe, for the New York suburbs (Floyd Dell, Max Eastman, and Boardman Robinson, the contemporary cartoonist Marsh most admired, made Croton-on-Hudson a suburban bohemia), or the Southwest (Mabel Dodge Luhan and, at least part-time, John Sloan). A number became more conservative in their outlook. Floyd Dell, the arch supporter of feminism and free love in the teens, advocated monogamous marriage and stable sexual relationships by the 1920s—a revised new womanhood.[36] Many felt that the Village had lost its sense of serious artistic purpose and had turned into a haven of commercialism, tourism, and pseudo-bohemianism. Speakeasies attracted outsiders and rents climbed (prompting a number of artists to look to Fourteenth Street for cheaper studios). In Exile's Return , Malcolm Cowley distinguished the individualism of his own apolitical "lost" generation of the 1920s from the collaborative socialism of earlier intellectuals: " 'They' [the earlier group] had been rebels: they wanted to change the world, be leaders in the fight for justice and art, help to create a society in which individuals could express themselves. 'We' were convinced at the time that society could never be changed by an effort of the will."[37] The distinction Cowley made is like that between prewar activist feminism and post-franchise individualized feminism.

Throughout the twenties Marsh gave full attention to advancing his career. He filled his time with schooling and educational travel and took advantage of exhibition opportunities and illustration assignments. He must have decided to study painting almost immediately after coming to New York because he took painting classes from John Sloan and Kenneth Hayes Miller during the 1921-22 season at the Art Students League. Marsh's "conversion" to painting and his increasing respect for the old masters began seriously with a six-month European trip to Paris, London, and Florence beginning in December 1925, followed by more study with Miller. By the end of the decade, Miller and Marsh had forged a close personal friendship along with what would be a lifelong student-teacher bond. Marsh would later claim that he showed Miller everything he made. In turn, Miller encouraged Marsh not to forsake the working-class urban subject matter and sketchy illustra-

tor's style he had learned from Sloan but rather to integrate his love for the old masters with his more inclusive reportorial approach.[38]

Marsh's decision to become a painter and his respect for the canonical works of old master painting cannot be considered surprising given a family background rooted in the American academy and a Yale education that emphasized the heritage of Western European thought and culture. In 1923 he married Betty Burroughs, a fellow student at the Art Students League, whose father, Bryson Burroughs, had been curator of painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art since 1907. Throughout their marriage, which ended in divorce in 1933, Marsh and Betty resided in the Burroughs family home in Flushing. This environment continued his early connection to the world of art and fueled his desire to extend the tradition of high European art to the American scene.[39]

Betty ultimately found that Marsh, despite his family's wealth and his ties to the conservative art world, behaved in ways that made her feel rootless and kept the two of them from settling into the family life she eventually desired.[40] Though biographers and close friends described him as a shy and gentle intellectual who read Shakespeare, Dante, and Proust, Marsh was frequently rough edged, his interactions abrupt. Edward Laning characterized him as a Jimmy Cagney gangster type, a "tough dead-end kid" who spoke out of the side of his mouth.[41] Social interactions were not always smooth, though Marsh's detailed diaries from 1929 through the 1930s show that he led an active social life. Close friends, like Miller, Bishop, and Laning, another pupil of Miller's who also painted Fourteenth Street subjects in the early 1930s, made their way to the Burroughs family home on Sundays. Marsh had regular lunch, dinner, and movie engagements, and frequently attended art openings. In fact, the diaries describe a frenetic pace of working and socializing combined with an emerging pattern of success that left little room for family life. Even when Marsh inherited an estate of close to $100,000 on his grandfather's death in 1928, he chose to remain in the Burroughs family enclave rather than move to a new home. In 1928 he supplemented the Flushing workplace with his first Fourteenth Street studio, at 21 East Fourteenth Street. By this time he had been an established illustrator for seven years, was fully committed to his study of painting, and had expanded his work into printmaking (etching and lithography) and watercolor (a medium that brought him his first one-man shows). The new studio location gave Marsh, who was seldom without a sketch pad, direct access to neighborhood subjects that would occupy him for the next several years—the burlesque houses, the young women on Fourteenth Street subway platforms, and, by the early 1930s, the neighborhood's unemployed men. Moreover, his new studio was only a few doors away from Miller, Bishop, and Laning. In this way, he strengthened already close personal and artistic ties.

Marsh's growing success, his additional studio space on Fourteenth Street, and changing expectations for family life on his wife's part brought out differences that

culminated in divorce. The ten-year marriage records many of the tensions of the shifting practices and discourses attached to new womanhood in the interwar years. Betty Burroughs had been an archetypal urban flapper in the early 1920s—bright, well-to-do, and, like her future husband, caught up in the fast pace of postwar city life.[42] Her letters to Marsh, many written from Ogunquit, Maine, where she summered with friends, urged him to come up to parties. Her prose is punctuated with contemporary slang. She often referred to Marsh as "you Old Thing," and she signed her letters "s'long." Several early letters project a certain level-headed cool:

Say, young feller me lad, you worry your Auntie when you write her affectionate letters. It ain' that she minds your being affectionate (Lord knows, you do it at your own risk) but she suspects such sentiments to be subject to change without notice to the public. In other words I don't respect the impulses of a moment. . .. Be sure of constancy before expressing affection. Not that anyone can avoid pain in these matters of the heart—but perhaps the amount can be reduced by a little judicious forethought. I think my heart is the consistency of cold pea soup. Anyhow, it is not to be allowed to get the jump on me without the full approval of my head. I don't believe in the one love of a lifetime stuff but on the other hand, falling in love is too serious a matter to indulge in unless you are banking on it lasting a reasonably long time.[43]

Betty's prose makes the strong declaration of independence required of the 1920s flapper. In another letter to Marsh, dated July 19, 1923, Betty chastised him for being too dependent on her, asserting her independence but also revealing an anxiety typical of the period: that there might be too great a reversal in traditional gender roles. Ultimately, she calls on Marsh to go his own way, to "conceal" some of his need for her:

Your first letter gave me a horrid sick feeling. You said something about being a barnacle—cleaving to me as to a rock. . .. But seriously, ye Gods, Reg, there is an awful grain of truth in it and I won't face life with you on my skirt tails—Life my child is a rocky road at best and with an inert drag behind—Please assure me that you will go your own gait—a good swift, clear-headed pace—and may even be able to give me a hand up over bad spots. What a sensitive soul you are. There are things I want to ignore (like your feeling of dependence on my energy) but you feel them and haven't the wit to conceal.[44]

While Marsh was in Reno in the winter of 1933 awaiting their divorce, he received several letters from Betty that suggest how changing definitions of independence, dependence, and the sexual freedom permissible in a companionate marriage all entered into their decision to part. Betty, who had wanted a child, gave birth to a son, Caleb, in July 1932; early in 1934 Marsh gave the child over for adoption to the man Betty married.[45] Marsh's career had blossomed more rapidly than Betty's, and he became more preoccupied with his own work and grew apart from her. Betty, who ten years earlier had cautioned Marsh about his dependence,

now spoke of her own need for an "absorbing, exclusive love," one she believed her new husband would be able to give her.

Following his divorce Marsh returned to New York, where he engaged in a ten-month flurry of social activity before marrying the painter Felicia Meyer in January 1934. His diary entries for 1933 suggest that he floundered during this year between marriages: they were garbled and cryptic, the writing often sloppy and illegible where before it had been neat. (Since childhood, Marsh had kept careful journals in which he recorded all social activities and everything from the weather to the number of paintings, watercolors, and etchings he did in a month.) Moreover, the content of the entries shows changes in his life. His earlier work patterns—painting by day, working on prints in the evening—seem more erratic. He dined out almost every night or, with the repeal of prohibition, met friends for cocktails. Occasionally he noted his hangovers.[46] During this period Marsh devoted less energy to painting, more to cartoons and etchings. Marilyn Cohen has suggested that although the Depression accounted for Marsh's expanding his subject matter to include images of unemployed men, events in his own life during 1933 also contributed to the proliferation of scenes showing drunken vagrants and Bowery derelicts.[47] In an entry for November 25 Marsh first mentions Felicia Meyer, his future wife. After their initial lunch date, they were together nearly every day for lunch, dinner, and dances. Marsh went to her family's vacation home in Dorset, Vermont, for Christmas, and they were married the following month. At that time they moved down the street from the apartment Marsh had occupied since his divorce (at 11 East Twelfth Street) to 4 East Twelfth Street. For the rest of his life, Marsh's studio would never be more than two blocks from his apartment, which housed his etching press.[48]

Marsh's life without a partner—to judge from his diaries and accounts by friends—lacked structure. In 1934 Marsh resumed his regular working habits; he became enormously productive again and made some of his best work. His own desire for structured work time emerges in affectionate triweekly correspondence with his new wife, Felicia (whom he called Timmy), the following summer. (Like Betty, Felicia left New York for New England in the summer to paint landscapes.)[49]

To a greater extent than is apparent with any of the other artists, biographers and interpreters of Marsh's life have deployed psychoanalytic categories to describe his personality and his art in terms of generational tensions and gender conflict. Marilyn Cohen, whose interpretation of the self-referential side of Marsh's art will be taken up more fully in Chapter 5, argues that the repetition of subjects and themes has as much to do with his psyche as with his wish to chronicle the urban scene.[50] Both Lloyd Goodrich and Edward Laning focus on Marsh's extreme competitiveness, connecting it to his need to affirm his masculinity. It is revealed in Marsh's childhood diaries, where he gauged his self-worth according to his athletic achievements.[51] Lloyd Goodrich explained that Marsh "always tried desperately to act like a perfectly normal boy interested chiefly in sports and fights." He was

interested, in other words, in asserting his masculinity against the more genteel pursuit of art as practiced at home by both parents.[52]

His competitiveness continued into his adulthood. Laning recounts two events that reveal Marsh's continuing need to assert his virility:

One night, it must have been about 1933, I went to dinner with Reg and Jacob Burck (then the cartoonist for the Daily Worker ), and after dinner we went back to Reg's place. He was then living alone, between marriages. In his top floor apartment on Twelfth Street he had installed his etching press. When we entered, he looked at the press and said to us, "John Curry was here this afternoon. He put his shoulder under that press and liked it off the floor!" Reg took off his jacket and lunged at the press. He struggled until the sweat poured from his forehead. He couldn't budge it. Some years later on a government art assignment during the Second World War, his ship crossed the Equator and he was "hazed." He was blindfolded and required to "walk the plank." Reg didn't merely jump as he was commanded to do. Instead, he posed on the board and dived into the empty canvas tank—and broke his arm.[53]

As time went on, Marsh's intense competitiveness channeled itself into his artistic production, over which he maintained strict control. Never without a sketchbook, he drew and painted by day and kept track of the number of evenings he etched every month and the number of sketching trips he made to Coney Island. Determined to excel in every medium—as an illustrator, cartoonist, painter, muralist, and printmaker—he produced an extraordinary quantity of work, some of poor quality because of his experimentation. He also wanted to be involved in all aspects of the art world. He served on the Art Students League board and eventually taught year-round, even though he was financially independent. His artistic activity, fueled by a desire for success, was also, as Marilyn Cohen has argued, driven by a need to prove himself "as a man."

A number of Marsh's friends, among them Raphael Soyer, suggested that his competitiveness contributed to his early death. Soyer, who depicted Marsh at work in the early 1940s with an etching plate in his hands, recalled that Marsh's "prodigious" energies made it impossible for him to pose unoccupied for what was to have been a more straightforward portrait.[54] Laning, somewhat cynical himself about American cultural stereotypes of masculinity, characterized Marsh as the victim of the Hemingway syndrome:[55]

Like all the American boys, Marsh was overreaching himself. Like Fitzgerald, Pollock and Hemingway, he killed himself. Or something in our culture goaded him, and them, beyond human endurance, and we killed them. Miller always told us "know your limitations," but this is the lesson that the American Boy, even the most studious, never learns.[56]

According to Laning, Marsh's tough exterior was a facade for a vulnerable, shy, and gentle person who competed to win the approval of those on whom he was

dependent. Marsh confessed his deep insecurity to Raphael Soyer when he told his fellow artist that he was undergoing psychoanalysis. He confided to Soyer that every time his mother had left him for even a short period of time, he had feared she would never return.[57] Marsh evidently longed for his father's approval, rarely forthcoming in a relationship Laning has described as "strained and difficult." An academic painter, Fred Dana Marsh was unable to accept Marsh's energetic and fundamentally unacademic style. Marsh's late 1920s representations of working men building skyscrapers and his interest in mural painting may have been attempts to please his father by repeating his themes or to compete with his father's own earlier successes. Marsh's family, concerned about his preoccupation with illustration and lower-class subjects, may have encouraged him to work with Miller, the most academically schooled and tradition-minded teacher at the league. Ironically, Miller encouraged Marsh to retain the most sexual, and hence "improper," side of his art. According to Laning, Marsh's subsequent dependence on Miller occurred in part from a need for a substitute father figure.[58]

However personal Marsh's need to affirm his masculinity may have been, it was also cultural. During Marsh's boyhood the reinvigoration of middle-class manhood was envisioned as an antidote to the loss of personal autonomy accompanying the shift from an individually controlled home-based economy to a consumption-oriented industrial one. Masculine vigor would make American commerce more competitive. As for the artist, the rough masculine type admired by Robert Henri and some of his followers would counter the notion of the artist as a feminized type, operating at the periphery of American culture, as Marsh's parents did by the teens. As Marsh came to artistic maturity in the 1930s, he witnessed the greatest challenge to date to the long-standing link between masculinity and work as millions of men lost their jobs. Though never in financial danger, Marsh used work as a means to personal autonomy, a reaffirmation of his masculinity, and, with that, an affirmation of the centrality of the (male) artist in American society.

Isabel Bishop

Based on her professional successes and personal life, the values she espoused, and her ability to negotiate the more open but still male-dominated art world of the 1920s and 1930s, Isabel Bishop's position as a second-generation New Woman is secure. Described by all who knew her as dignified, articulate, and diligent about work, yet modest and ladylike in demeanor, Bishop seems to have achieved that delicate balance between femininity and self-sufficiency that characterized the revised New Woman. Like Marsh, Bishop came from an upper-middle-class background. Her family valued education, encouraged her to become financially autonomous, and gave her the means to achieve her goal. At the same time, by virtue of her circumstances and her sex, her situation in relation to the prevailing ideologies

of gender and class was different from that of Miller and Marsh. Reviewing her life in the 1920s and 1930s from the vantage point of the 1970s and 1980s, Bishop noted the contradictory position she occupied as a woman artist. Even where she avoided interpreting her experiences and choices in feminist terms, her narrative discloses points of discomfort and contradiction as she moved through an established gender system.

Bishop's parents were descended from old, prosperous, and highly educated East Coast mercantile families.[59] Sometime in the 1880s they founded a preparatory school in Princeton; Bishop's father was a scholar of Greek and Latin, her mother an aspiring writer. By the time Bishop was born, in 1902, the youngest of five children by thirteen years, her parents had abandoned their dream of running the school. With the birth of the first of two sets of twins, her mother was overwhelmed by the combination of childcare and administrative responsibilities. Her parents suffered a number of disappointments during Bishop's youth. After giving up their school, they moved to Cincinnati (Bishop's birthplace), where her father worked first as a teacher and then as principal of the Walnut Hills School. When Bishop was about a year old, they moved to Detroit, where her father accepted a poorly paid job in a high school, teaching Greek and Latin; later he became principal. Just as she graduated from high school at age fifteen, he was fired for administrative incompetence, a charge Bishop remembered as trumped up to make her father a scapegoat.[60]

Throughout her childhood, Bishop's parents depended on the financial generosity of James Bishop Ford, her father's wealthy cousin. When her father lost his Detroit job, Ford found him a position, complete with residence, in a military academy that he had endowed. Earlier, his help had made it possible for the family to maintain living standards barely above genteel poverty. For a time in Detroit they lived in a marginal working-class neighborhood adjacent to a wealthier one. Bishop recalled learning about class divisions at an early age when her parents ordered her not to play with neighborhood children who were "different."

Throughout Bishop's childhood and adolescence, class anxiety and gender difference assumed the various forms typical of the period. Bishop's mother, an early feminist, worked for women's suffrage and urged her daughters toward the independence that had been unavailable to her once she started her family. Bishop was a late arrival to the household; her mother once told her that she often felt more like a grandmother than a mother. Bishop's college-age sisters assumed parental roles when home on vacation, prescribing her dress according to gender codes.

They would go off to college and when they came home they'd pick up their interest in me, like a parent. . .. One of my sisters had me in Eton collars and tunics; then she went off and another came home and disapproved of those dull clothes and put me in some fancy little things. Everyone was trying to do something to me, except my mother. She was indifferent.[61]

To avoid housework and childcare, Anna Bishop turned to her pet project—a translation of Dante that she undertook after teaching herself Italian. Though Bishop later understood the restricting demands placed on her mother by the conventions of middle-class life, she often felt alone during her childhood, ambivalent about the distance her mother placed between them. Her father, more sympathetic to her, perhaps because he saw himself as something of an outcast, took her on as his "special interest." Although she loved and respected him, Bishop "hated" the division of her family into camps; her father openly placed her and himself in opposition to her mother and her siblings.[62]

Bishop's art education began at age twelve, when her parents enrolled her in a Saturday morning life drawing class at Detroit's John Wicker Art School. Given her age and a substantially restrained upbringing, her first encounter with the heavy-set female nude was a shock, but it gave her a headstart in what was usually considered more advanced training. When Bishop graduated from high school, at age sixteen (just after her father lost the Detroit job), she was sent off on her own to New York. There she became one of a number of proper young ladies studying illustration at the School of Applied Design for Women and living at the Misses Wilde's boarding house on the Upper East Side. Her parents wanted her to earn her own income, and an occupation in the graphic arts, with training acquired in a relatively protected environment, seemed the safest route. Bishop thus entered New York under very different circumstances and within different social spaces from Marsh, the twenty-year-old Yale graduate.

Within two years Bishop had grown dissatisfied with her training and her restricted environment. Even though she had been able to move directly into the life drawing class at the School of Applied Design for Women, the school itself failed to meet her needs. In the summer of 1919 she went to Woodstock, the popular artists' colony, to take a life course taught through the Art Students League. In 1920 she decided to abandon graphic arts and move toward a career in painting. James Bishop Ford, her father's cousin, who had already supported her early schooling, agreed to extend her monthly stipend so she could concentrate on her education; he would remain Bishop's patron for well over a decade.[63]

Bishop left the Misses Wilde and moved to the Village with two other women. In her first season at the league, she capitalized on the loose structure that allowed students to sign up for different classes every month. Her enrollment card records a smorgasbord: life classes with Miller; painting with the academic artist DuMond; advanced modernism in Max Weber's course on late cubism; and lectures by Robert Henri. Weber was highly critical of her work and, not surprisingly, the eighteen-year-old Bishop felt intimidated. From Henri she recalled learning the value of experimentation. She was "fascinated" by Henri but "frightened" and "too scared to put out anything for criticism."[64] By the end of the year, Bishop had found her mentor. During the entire 1921-22 league season she studied life drawing and

painting exclusively with Miller. The following season, 1922-23, while living on Eleventh Street in Greenwich Village, she added an afternoon studio with Miller. There she would have begun her friendship with Reginald Marsh, who was taking his second round of Miller courses. That summer she met and studied briefly with Guy Pène du Bois.

The years 1923 to 1926 were difficult for Bishop, both personally and artistically—in part because of new possibilities for women: "It was a time of freedom for women to do what they wanted to do, but freedom can be intimidating."[65] She moved to 21 Perry Street in the Village and set up a studio at 15 East Eighth Street, determined to be an artist. But she had difficulty managing all aspects of her life:

I went out to be an artist. I painted little brown pictures that were too dark but they weren't invalid. I can still bear to look at them today but I couldn't stand the isolation. I was desperate. I thought of just disappearing, just dropping out of the world. I thought of suicide, of becoming an alcoholic (although I never went to bars). Then it occurred to me that I should go back to the League so that I would be with my peers. I then would have some part of my day structured because I found I was sitting up all night and sleeping during the day. I was a disorganized person.[66]

During these three years, Bishop spent only four months in Art Students League classes. With the encouragement of Pine du Bois, she exhibited three small works in two Whitney Studio Club shows. Then, at twenty-four, she made three attempts to commit suicide over an unsuccessful love affair.[67] By that time, Bishop was desperate for both colleagues and a more structured existence. She moved her studio-living quarters to 9 West Fourteenth Street, a second-story space opposite the entrance to Hearn's department store and a block away from Miller. She returned to the league as a "graduate" student, and for the next five seasons, through May 1931, spent all or part of the school year studying with Miller. By that time, Miller had begun teaching his mural-painting class, which featured advanced study in Renaissance formal principles. That summer, after she completed her studies, Bishop, Miller, and Laning sailed to Europe to study old master painting in Paris, London, and Madrid museums. Bishop embarked on another European tour in the summer of 1933, accompanied by Miller and Marsh.[68]

Bishop's apprenticeship—both her formal training and the time she spent preparing a body of work for exhibition—was a long one. For the rest of her life her methods of working would be painstaking and slow, her output small. Some of her first earnings came through portraiture. A home for the aged in Peekskill hired her to paint portraits from photographs, and she recalled that either in 1930 or 1931 she felt proud to pay income tax for the first time. In 1932 Alan Gruskin, a young Harvard graduate enthusiastic about American art, invited Bishop to be one of thirty artists to join his new venture, a cooperative gallery in Manhattan. For the sum of five dollars per month, artists could participate in a continuing group exhibit and also have one-person shows. Bishop joined in 1932 and in 1933 held her first

solo exhibition featuring seventeen works including still lifes, a self-portrait, small Union Square panoramas, and even two golf scenes. In three more one-person exhibitions (in 1935, 1936, and 1939), group shows, and national exhibitions she showed her genre paintings of young working women. Museums began to purchase her works, and she began to receive awards and increasingly positive reviews.[69]

In the summer of 1934, when she was thirty-two, Bishop married Dr. Harold Wolff, a neurologist who worked at New York Hospital and later became well known for his work on such diverse topics as brainwashing and headache pain. At the time of her marriage she moved her studio from Fourteenth Street to 857 Union Square West (overlooking the public speakers' platform at the north end of the square), where she would remain until 1984. In interviews with Helen Yglesias shortly before her death Bishop discussed both the implications of her choosing to marry and the circumstances of her marriage,[70] suggesting how her choices were economically and socially different from those made by her male artist friends. Her comments also open up issues of influence for male and female artists in general and for Bishop herself in particular.

Bishop claimed to have married Harold Wolff out of "desperation" to extend the conditions she had established over the years as essential to her life—uninterrupted time and financial support for the single-minded pursuit of her art. By 1934 she was in the process of breaking away from two important systems of support, both male. After nearly fourteen years she could no longer rely on her father's wealthy cousin, and, having signed a contract with Midtown Galleries, she felt even more keenly her commitment to being a professional artist.[71] At the same time, Bishop was re-evaluating her aesthetic allegiance to Kenneth Hayes Miller, her longtime friend and mentor. This re-evaluation was complicated by Miller's anti-individualistic aesthetic pronouncements in the mural-painting class and by her responses to that teaching as a woman student in the late 1920s in a male-female teacher-student relationship.

In his teaching Miller expressed the belief that modern French painters like Picasso and Matisse sacrificed an important social function of art—the communication of an idea about contemporary life—to create paintings that embodied only an immediately recognizable artistic personality. To counteract this tendency, he argued that the art of mural painting should be collaborative and anonymous. Miller never suggested that all artists work together to produce a single mural; for him collaboration meant that everyone should work from similar principles of Renaissance composition to de-emphasize individual style.

Bishop was particularly susceptible to these ideas. When she returned to the league to study in 1926, it was with a clean slate; unlike Marsh, for example, she had not already worked for several years as an illustrator or made trips abroad to study art. She had not adopted a particular subject or a method of working. Furthermore, as a woman, she had long been subject to the instructional and prescriptive content of male discourse. She was, as she described it later, much more willing

than other students to accept Miller's doctrines, as a result of which she produced a number of works in the five-year period 1928-33 that were immediately recognizable to critics and friends as those of a Miller student (see Figs. 2.2 and 3.7). When she came to understand how Miller's values might be holding her back, she began to work more consciously to develop her own painting technique and subject matter.[72] As the economic, social, and intellectual circumstances of Bishop's life and career shifted, "marriage resolved the desperate difficulties. So, you see, I felt I had no other choice."[73]

By the 1930s already powerful prescriptions against the combination of marriage and career for middle- to upper-middle-class women escalated. Based on her observations of both her mother's thwarted career, with its effects on her childhood, and her few women friends' struggles to balance traditional wifely duties with artistic aspirations, Bishop's fears of marriage seemed well grounded. As she recalled it later, in an acute summary of the modern New Woman's dilemma, the marriage of her close artist friend Katherine Schmidt to her fellow artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi embodied the conditions she hoped to avoid.

Yasuo Kuniyoshi's first wife was a close friend, Katherine Schmidt, a very distinguished artist. She was very young when they married. She tried to do everything. They lived in Brooklyn Heights. She came into Manhattan every day to work in the lunchroom of the Art Students League. Katherine kept a meticulous house and did the rounds of the dealers with her husband's work, Kuniyoshi's work. All that while painting some of her own best pictures. I didn't know that I could function like that.[74]

After fifteen years of maturing into a serious professional artist, Bishop had experienced enough of the artistic community to know that her long searching process of production, not to mention her temperament, required quiet, uninterrupted hours in a studio separate from her domestic environment. Harold Wolff enthusiastically supported her endeavor in a way that was atypical for a male of his generation, profession, and character. Formal and unyielding, Wolff was evidently feared by students and colleagues for his obsessive and uncompromising demands for perfection even in insignificant details. His authoritarian hand operated on the home front as well. Friends recalled dinner parties orchestrated and presided over by Wolff, who distributed cards that listed times for each event (including the hour for departure), intervals of silence for music, and topics of conversation. On such occasions, Bishop graciously played the part of docile spouse. For the first fifteen years of their marriage, Wolff's mother lived with them. She provided some childcare when their son, Remson, was born in 1940; her presence, as Bishop characterized it, was both "helpful" and "difficult."[75]

Bishop's life encompassed a series of inconsistencies, and she was obliged to occupy or negotiate contradictory subject positions. She possessed all the old-fashioned attributes of a gracious lady—she was quiet spoken, generous, and con-

ciliatory to a fault.[76] At the same time, she was professionally ambitious and as fully committed to her work as her male artist friends and her husband. To achieve her goals—many of them predicated on an economic and social independence that the culture neither sanctioned nor made easy for women to attain—she had to tread a precarious path between independence and dependence on men in positions more powerful than her own (her father, her wealthy relative, Miller, and finally her husband). Bishop claimed that her relentless pursuit of her career rather than marriage kept her second cousin James Bishop Ford interested in maintaining her stipend; he would not have continued to support a man for such a long time. Her husband, who was passionate about music and art, was proud of her accomplishments but also undoubtedly impressed with the correspondence of her rigorous six-day work routine to his own. In exchange for what may have been his overwhelming exactness in domestic affairs, Bishop gained his respect for her professional needs. "We left the house together every morning," she remembered. "He went on to his work and I went to my studio. There was never any question about it."[77]

Their union was a version of the modern companionate marriage, forged out of mutual respect rather than romantic love and, perhaps on Bishop's part, out of economic and cultural necessity: women married. A revealing letter from Reginald Marsh to his wife Felicia, dated August 9, 1934, conveys the precipitousness with which Bishop married once her decision was made and the way the marriage from its inception was fully integrated with her working life:

Guess what—Isabel walked into my studio at about two o'clock today, started looking around as usual, and with a sudden shy exclamation uttered a most astonishing—"I just got married half an hour ago." What, what, wonderful [indistinguishable word] congratulations, let's have a drink? "no, no, I am going back to my studio to get to painting—painted all morning, suddenly decided to get married at noon." Well, who's the man—husband? Dr Wolfe, you met him at our [i.e., Marsh and Felicia's] house this winter.[78]

Bishop's early career in institutional situations was similar to that of her male counterparts. In fact, at an early age she left woman-centered instructional and living situations to compete on her own in established centers for making and exhibiting art. When she confronted decisions complicated by her status as a woman painter, she never looked to woman-centered organizations for support. Her choice of individual over collective achievement was not only the dominant model in the culture at large but also one given official sanction by important female critics in the art world itself. In separate reviews on the occasion of the fourth annual exhibition of the New York Society of Women Artists in February 1929, the critics Margaret Breuning of the New York Evening Post and Helen Appleton Read of the Brooklyn Eagle condemned the society, not for the quality of the work shown, but for its very existence. Breuning asked:

Where are the organizations of artists that these ladies, now exhibiting, wish to join and cannot because of their sex? What galleries are closed to them as women? Why should the New York Society of Women Artists, however admirable their exhibition may be, exist, except as a confession that its members do not wish to compete with their masculine confreres, but desire the immunity of feminine fragility to be extended to them.

Evidently under this aegis they desire that their work shall not be judged with impartiality, but with chivalry and the tacit watchword of the Old South. "Gentlemen, remember that she is a lady." . . . But why should young women who pride themselves on being modern revert to the doubtful protection of outworn procedure and band themselves together in this clinging vine sort of attitude?[79]

Read echoed Breuning's sentiments: "The issue at stake is, Why have a women's organization at all? The time has passed when women need to band themselves together in order to break down the prejudice against the possibility of feminine accomplishment in art."[80]

The powerful perception in the discourse of revised new womanhood that women had achieved equality with men thanks to the franchise blinded both Breuning and Read to the inegalitarian conditions of the art world and the art market, not to mention sanctions against married women following careers. Moreover, both writers accepted the companionate ideal promoted by social scientists and psychologists, who labeled "female-centered sociability as deviant."[81] To operate successfully, these critics seemed to claim, one needed to participate in the "normal" art world of male-female relationships. Like Bishop, who never joined these groups, women and men alike agreed that individual accomplishment was a matter of individual responsibility. Whether or not Bishop was fully conscious of her choices, at the time, she either found, or was fortunate enough to have presented to her, a way to proceed in the art world as a woman making art perceived worthy of being judged alongside that of her male peers.[82]

Raphael Soyer

Although Bishop's position in the contradictory discourse of mainstream new womanhood complicated her personal life and career, thanks to outside support she had educational opportunities that brought her to the center of the art world by the 1930s. Moreover, she could move in circles with artists of her own social, educational, and class background, many of them involved in organizing institutions of support for artists throughout this period. Unlike Bishop, who would always be marginalized by a gender system that placed women outside the normalized model of male artistic achievement, Raphael Soyer was marginalized by socio-economic conditions, immigrant status, and personal circumstances that initially denied him

the educational and social opportunities that placed Marsh and Bishop at the center of the art world. At the same time, however, Soyer's intellectual environment and cultural tradition made him sympathetic to exploring artistic conventions compatible with those adopted by other members of the Fourteenth Street School. By the 1930s, because of his background and his imagery, Soyer came to exemplify the successful American immigrant artist.

The biographical narrative of Raphael Soyer and his twin brother, Moses, contains many of the same tropes of the artist's childhood as that of Reginald Marsh. Raphael was the sickly twin who almost died at birth; both his parents were "artistic," and they encouraged their children to draw (three of the six children—Moses, Raphael, and their younger brother Isaac would become professional artists). Just as Marsh found his subjects in the popular culture of his childhood, Raphael Soyer became a "confirmed realist" with a desire to "paint people" after watching one of his father's students do a drawing from life.[83] But Soyer's circumstances were dramatically different. He and his twin, Moses, were the oldest of six children, born in 1899 in the small Jewish community of Borisoglebsk, Russia. Raphael's father, Abraham, was a scholar and teacher, "employed by the fifty or so aristocratic Jewish families to teach their children Hebrew."[84]

Although the family was poor, Abraham's position as a scholar, rather than an artisan or factory worker, gave them status in the community and later in America.[85] It also gave them access to literature and art. By the time they had been admitted to the local gymnasium at age twelve, they had read much of the Russian literature in their father's study, including works by Dostoyevski, Chekhov, and Tolstoy; in Russian translation they devoured Dickens, Thackeray, and their favorite American novels, Tom Sawyer, Uncle Tom's Cabin , and The Prince and the Pauper . Their parents decorated their living space with works by their own hands and postcard reproductions of Russian works and old master paintings; in particular, their father introduced them to Rembrandt, Raphael, and Michelangelo.[86]

Their early life also had a political dimension. Raphael recalled being taken to Zionist meetings with the other older siblings, Moses, Fannie (a year and half younger than the twins), and Isaac. The Soyer home also served as a congenial meeting place for young Jewish intellectuals. By the autumn of 1912, however, these gatherings aroused the suspicion of czarist authorities. The governor of the province refused to renew Abraham Soyer's residence permit, making the Soyers victims of the widespread oppression of Jews that escalated after the failure of the 1905 revolution. Within the month, the entire Soyer family made their way to Liverpool and then Philadelphia, their passage paid for by a Philadelphia relative. They were part of the last wave of Eastern European Jews who immigrated to America. (Between 1881 and 1914 approximately one-third of the population immigrated.) Several months after arriving, according to Raphael, Abraham Soyer found work in New York, writing for commercial Yiddish publications and teaching Hebrew.[87]