2. Structure and Social Base

3. Organization

To understand the manner in which Mawdudi’s ideology found organizational expression and the extent to which it found a social identity and put down roots among various social strata, to understand what makes for the Jama‘at’s strength as a political actor and, conversely, accounts for its political constriction, and to outline the structure, operation, and social base of the party, one has to identify the variables that have determined the Jama‘at’s organizational structure and base of support and controlled the extent of continuity and change in them, and to account for both the support for the Jama‘at’s program among particular social groups and the limits to the diversity of its social base. The links between the Jama‘at’s ideology and politics and the pattern of the party’s historical development have grown out of its organizational structure and social base, as have the nature of the Jama‘at’s politics and its reaction to changes in its sociopolitical context. By defining the Jama‘at as an organization with a distinct social identity and distinguishing those factors which have determined the extent of its power and reach, we can establish a basis for understanding the party’s history as well as the nature of its politics. We will examine the way the Jama‘at has contended with organizational change and the problems it encountered in trying to expand its social base. Organizational change led to debates over the choice of leaders and how to reform the party’s organizational design. Opening the ranks of the party also generated debates that influenced its ideological development and politics. Those factors interacted with influences that were brought to bear on the party by other political actors to decide the nature and trajectory of continuity and change in the Jama‘at’s politics and the party’s role and place in society.

| • | • | • |

The Jama‘at-i Islami’s organization initially consisted simply of the office of the amir, the central majlis-i shura’, and the members (arkan; sing., rukn), and this did not change much during the party’s early years. Members were busy producing and disseminating literature, especially the Tarjumanu’l-Qur’an, expanding its publications and education units at Pathankot, and giving form to the Arabic Translation Bureau (Daru’l-‘Urubiyah) which was established in Jullundar, East Punjab, in 1942.[1] Between 1941 and 1947 supporters were divided up according to the extent of their commitment to the party. The hierarchy that resulted began at the bottom with those merely introduced to the Jama‘at’s message (muta‘arif), moved up to those influenced by the Jama‘at’s message (muta‘athir), then the sympathizers (hamdard), and ended with the members (arkan). The first three categories played no official role in the Jama‘at aside from serving as a pool from which new members were drawn and helping to relay the Jama‘at’s message. All categories provided the Jama‘at with workers (karkuns) of various ranks employed by the party to perform political and administrative functions. They also served as workers in the party’s campaigns.

The hierarchy was revised in 1950–1951 to streamline the Jama‘at’s structure and tighten its control over its supporters in preparation for the Punjab elections of 1951. The categories of those merely introduced to and of those influenced by the Jama‘at’s message were eliminated and a new category, the affiliate (mutaffiq), was added. Affiliates were those who favored an Islamic order and supported the Jama‘at but were not members. They were, however, under Jama‘at’s supervision and were organized into circles and clusters.[2] Affiliates stood higher in the Jama‘at’s organizational hierarchy than sympathizers. The Jama‘at also devised a rational and centrally controlled structure which enveloped all of its affiliates and organized them into local units and chapters. In 1978 the party had 441 local chapters, 1,177 circles of associates, and 215 women’s units. In 1989 these figures stood at 619, 3,095, and 554, respectively.[3] The affiliates as a category were provided for in the Jama‘at’s constitution and therefore had to abide by the code of conduct laid down by the party. Early ties with people acquainted with the Jama‘at’s message, originally so important to a movement with a missionary objective, were now severed, and the party turned its attention to strengthening its reach and its ability to run effective political campaigns. The change suggests that the Jama‘at did not associate political vigor with the expansion of its popular base, which would have been possible through extending its informal ties with the electorate but rather with organizational control.

After 1941, the Jama‘at was besieged with problems of discipline, and to solve them the party tightened its membership criteria a number of times. Mawdudi regarded these problems as serious enough to justify measures that would safeguard against the breakdown of discipline.[4] The party’s concern with politics, however, required a rapid expansion of membership which enforcing the new criteria would discourage. The category of affiliate was the solution; it brought many people into the party without compromising quality, caliber, and party orthodoxy. The new category also served as a screening device. It provided an opportunity to observe, scrutinize, and indoctrinate potential members before accepting them, reducing the problems of discipline in the party.

The institution of the affiliate points to the importance placed on moral caliber by the party. Membership in the Jama‘at began with conversion to the party’s interpretation of Islam. The party also demanded total commitment to its objectives and decisions. The members gave shape to the vision of re-creating the Prophetic community. Wives of members were encouraged to become involved in the women’s wing of the party and the children to join the student wings or children’s programs. Over time many Jama‘at members came to be employed by the party, and those who worked outside it were required to participate in its numerous labor and white-collar unions. Members often went to training camps, which educated them in the Jama‘at’s views and trained them in political and organizational work (see table 1).

| Punjab | NWFP | Baluchistan | Sind | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Organization Bureau of Jama‘at-i islami. | |||||

| 1974 | |||||

| Meetings | 9,272 | 250 | 2 | 2,412 | 11,936 |

| Training camps | 10 | — | — | 103 | 113 |

| Meetings with potential recruits | 299,137 | 3,000 | 688 | 328,063 | 630,888 |

| Missionary work training camps | 334 | — | — | 14 | 348 |

| Jama‘at-i Islami libraries and reading rooms | 1,578 | 71 | 12 | 179 | 1,840 |

| Conferences and conventions | 10,941 | 1,183 | 53 | 4,179 | 1,6356 |

| 1977 | |||||

| Meetings | 13,635 | 2,203 | 166 | — | 14,021 |

| Training camps | 114 | 23 | 2 | — | 139 |

| Meetings with potential recruits | — | — | — | — | — |

| Missionary work training camps | 4,000 | — | — | 38 | 4,038 |

| Jama‘at-i Islami libraries and reading rooms | 4,375 | 556 | 12 | 222 | 5,165 |

| Conferences and conventions | 46,175 | 3,335 | 77 | 5,620 | 55,207 |

| 1983 | |||||

| Meetings | 12,028 | 6,820 | 103 | 9,611 | 28,562 |

| Training camps | 799 | 593 | 32 | 186 | 1,610 |

| Meetings with potential recruits | 19,878 | 3,274 | 98 | — | 23,250 |

| Missionary work training camps | 121 | 157 | 4 | 132 | 414 |

| Jama‘at-i Islami libraries and reading rooms | 1,186 | 271 | 32 | 65 | 1,554 |

| Conferences and conventions | 4,423 | 1,114 | 57 | 225 | 5,819 |

| 1989 | |||||

| Meetings | 10,758 | 2,610 | 358 | 556 | 14,282 |

| Training camps | 137 | 61 | 18 | 35 | 251 |

| Meetings with potential recruits | 37,652 | 1,037 | 910 | 39,084 | 78,683 |

| Missionary work training camps | 75 | 4 | 2 | 22 | 103 |

| Jama‘at-i Islami libraries and reading rooms | 844 | 99 | 29 | 176 | 1,148 |

| Conferences and conventions | 2,753 | 242 | 53 | 924 | 3,972 |

| 1992 | |||||

| Meetings | 2,329 | 654 | 52 | 2,469 | 5,504 |

| Training camps | 361 | 93 | 7 | 101 | 562 |

| Meetings with potential recruits | 226 | 29 | 10 | 42 | 307 |

| Missionary work training camps | 2,390 | 403 | 19 | 2,098 | 4,910 |

| Jama‘at-i Islami libraries and reading rooms | 2,322 | 467 | 69 | 1,553 | 4,411 |

| Conferences and conventions | — | — | — | — | — |

Organizational unity was also boosted through frequent meetings at both the local and national level. Every Jama‘at unit held weekly meetings during which personal, local, and national issues were discussed, and every member gave an account (muhasibah) of his week’s activity to his superiors. If a member missed more than two of these meetings without a valid excuse, he could be expelled from the Jama‘at.[5] Since every local Jama‘at unit was part of a larger one, each of which held meetings of its own, members could end up attending several meetings each week. The Jama‘at sessions encouraged discussion and airing of views, but once a decision was reached, all discussion ended and the members were bound by it. National-level open meetings (ijtima‘-i ‘amm) promoted solidarity in the party as a whole. The Jama‘at began holding provincial meetings across India in 1942 and held its first all-India meeting in April 1945 at Pathankot. These meetings were held regularly until partition. In Pakistan the tradition of national meetings continued, but they were open only to members and affiliates. The party held its first national meeting in Lahore in May 1949 and the second in Karachi in November 1951. The extraordinary meeting at Machchi Goth was the most significant of these early all-Pakistan gatherings, which were not held at all between 1958 and 1962 due to the martial-law ban on congregations of this kind. They were resumed in 1962. In November 1989, for the first time in forty-two years, the party opened its national meeting to the general public, once again making use of the propaganda value which these meetings had for the party in its early years.

| • | • | • |

Party Structure

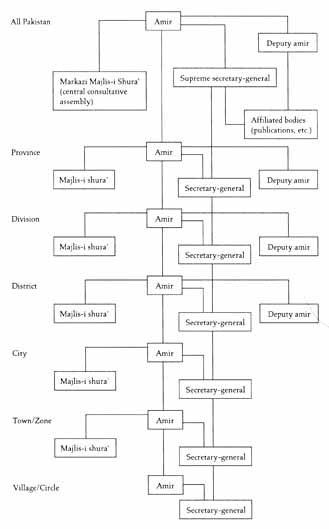

The hierarchy of members constituted only one aspect of the Jama‘at’s reorganization. Of greater importance were the offices which managed the party. After its move to Pakistan the Jama‘at began to deepen its organizational structure by reproducing the offices of amir, deputy amir, secretary-general, and the shura’, with some variations, at provincial, division, district, city, town/zone, and village/circle levels. Its structure was thus based on a series of concentric circles, relating the Jama‘at’s smallest unit (maqam), consisting of two or more members, to the organization’s national command structure (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Organizational structure of the Jama‘at-i Islami

Beginning in 1947 the Jama‘at began to organize its members at different levels. Over the years a hierarchy was formalized through which the party’s officials controlled the members at various levels. It remains in force today. Each level and unit are defined by the number of members in it and also try to accommodate the administrative topography of Pakistan. In places where there are few members, a unit may not be warranted on a village or town level. In such cases two or more villages form one circle, and two or more towns one zone. In administrative terms, a circle stands at the same level in the party’s hierarchy as a village unit, and a zone at the same level as a town. Each level has an administrative unit based on the authority structure of amir, deputy amir, shura’, and secretary-general, which is maintained through elections. To gain a sense of the depth of the structure, in Punjab alone there are thirty district-level units, each with an amir, shura’, and secretary-general. These circles envelope one another, producing an all-encompassing administrative and command structure, decentralized and yet closely knit to form the organizational edifice of the Jama‘at.

The Office of the Amir

The office of the amir was the first administrative unit created in the Jama‘at, and it has remained the most important. Originally the amir was elected by the central shura’ through a simple majority vote, but since the 1956 reforms he has been elected by Jama‘at members, and his term of office is fixed at five years; there is no term limit. A committee of the central shura’ members chooses three candidates, whose names are then put before the members at large. They send in their secret ballots to the Jama‘at’s secretariat, whose controller of elections (nazim-i intikhabat) has been appointed by the shura’ to oversee the process. A list of candidates must be put forth by the shura’ sixty days before the elections, and members must register to vote ninety days before the date of the election.[6] This system tends to favor the incumbent, as the members are not likely to unseat someone who is both administrative head of the party and its spiritual guide. No amir to date has been voted out of office.

The amir is the supreme source of authority in the Jama‘at and can demand the unwavering obedience of all members (ita‘at-i nazm). He is, however, constitutionally bound by the set of checks and balances that were passed following the Machchi Goth affair. All doctrinal issues must be determined by the shura’. Should the amir disagree with the shura’ on any issue, he has a right of veto which throws the matter back to the shura’. Should the shura’ override the veto, the amir must either accept the decision of the shura’ or resign from his post. The amir can be impeached by a two-thirds majority of the shura’. In budgetary and administrative matters the amir is bound by the decisions of the majlis-i ‘amilah, whose members he appoints from among shura’ members. The amir oversees the operation of the Jama‘at’s secretariat.

Insofar as possible this organization is replicated at each level of the party. Each lower-level amir is elected by the members of his constituency to terms varying from one to three years depending on the level in question. These amirs are similarly bound by the decisions of their shura’s. The lower-level amirs also oversee the office of their secretaries-general. However, lower-level secretaries-general are also accountable to the Jama‘at’s national secretary-general, which curtails the autonomy of the lower-level amirs and reduces their control over administrative affairs.

The Machchi Goth affair proved to be an aberration in an otherwise uneventful history of the amir’s office. Since then the constitutional mechanisms governing it have steered the Jama‘at through two succession periods—from Mawdudi to Mian Tufayl Muhammad in 1972, and from Mian Tufayl to Qazi Husain Ahmad in 1987. Each transition followed upon the retirement of the amir.[7] This pattern is in sharp contrast to transitions in other Pakistani parties, and accounts for the fact that the Jama‘at, unlike most other Islamic movements of South Asia, continued strong after the passing of its founder from the scene.

At a meeting in Lahore on January 10, 1971,[8] following the Jama‘at’s defeat at the polls in December 1970, a group led by Sayyid Munawwar Hasan (now the secretary-general) launched a tirade against Mawdudi. They argued that the Jama‘at had been routed at the polls because of him. Old and reserved, Mawdudi had relinquished national politics to the more energetic and charismatic leaders of the Pakistan People’s Party and the Awami League (People’s League), Zulfiqar ‘Ali Bhutto and Mujibu’l-Rahman, who won the elections. Similar views were related to the editors of Tarjumanu’l-Qur’an by other members and supporters during the following months.[9] Implicit in these ventings of frustration was a demand for a new leader. On February 19, 1972, Mawdudi suffered a mild heart attack and decided to step down as the amir. The shura’ nominated Mian Tufayl Muhammad (then secretary-general), Ghulam A‘zam (later the amir of Jama‘at-i Islami of Bangladesh), and Khurshid Ahmad (a longtime disciple of Mawdudi, and currently deputy amir of the Jama‘at). On November 2, 1972, Mian Tufayl Muhammad (b. 1914) was elected amir.[10]

None of those nominated by the shura’ qualified as charismatic leaders, least of all Mian Tufayl. The electorate appeared to have been governed by more pressing concerns than those posed by the party’s Young Turks. They had been disappointed by their performance in the elections and now faced a belligerent opponent in the Bhutto government. By choosing a loyal lieutenant of Mawdudi, an administrator rather than a political maverick, the party opted for continuity and stability. Its search for a more charismatic amir, although not abandoned, was postponed to a later time.

Mian Tufayl was not an effective politician, nor was he able convincingly to assert the powers vested in the office of the amir. Following his election, a good deal of the amir’s powers, accumulated and jealously guarded by Mawdudi over the years, were ceded to others in the party, and authority became more decentralized. That encouraged the formation of independent loci of power, which in turn further divested the amir of authority. Constitutional procedures became even more visibly entrenched, and the shura’, as the original source of authority in the Jama‘at, once again asserted its power and primacy. Mian Tufayl’s fifteen years at the helm of the Jama‘at, to the chagrin of those who had wished to reinvigorate the party’s ideological and chiliastic zeal, led the party farther down the road of legal-rational authority.

A different set of concerns led to the election of Qazi Husain Ahmad to the office of amir on October 15, 1987. After a brief surge in popularity in the 1970s, the Zia ul-Haq years had eclipsed the political fortunes of the party, which became increasing marginalized in national politics. The results were dissension within the party over its policies and performance and the retirement of Mian Tufayl. Aging, and increasingly under criticism, he stepped down as amir, paving the way for a new generation to lead the Jama‘at. The shura’ nominated Khurshid Ahmad, Jan Muhammad ‘Abbasi (the amir of Sind), and Qazi Husain Ahmad (the secretary-general) to succeed Mian Tufayl. The first two were conservative in the tradition of Mawdudi and Mian Tufayl, while Qazi Husain had a populist style and a good rapport with the younger and politically more active members. The party elected Qazi Husain (b. 1938). He came from a family with a strong Deobandi heritage. His two older brothers were Deobandi ulama, and his father was a devotee of Mawlana Husain Ahmad Madani of Jami‘at-i Ulama-i Hind, after whom Qazi Husain Ahmad was named. His Deobandi ties helped the Jama‘at in the predominantly Deobandi North-West Frontier Province. He became acquainted with the Jama‘at through its student organization and joined the Jama‘at itself in 1970. Many, among both the younger members and the conservative old guard, felt that it was time to go in a new direction. Qazi Husain had been responsible for creating an important constituency for the Jama‘at in North-West Frontier Province, which today elects a notable share of the Jama‘at’s national and provincial assembly members. Many hoped he would do the same for the Jama‘at at the national level.

Qazi Husain appealed to both conservatives and the more liberal elements. As the party’s liaison with the Zia regime during the Afghan war, he was favored by the pro-Zia conservative faction, while his populist style and call for the restoration of democracy endeared him to the younger generation who wanted the Jama‘at to distance itself from Zia. The Jama‘at had made a politically sagacious choice by electing an assertive and populist amir. His appeal has to date been more clearly directed toward the Pakistani electorate than toward the rank and file of the Jama‘at. He is the first amir to hold a national office: he has been a senator in the Pakistani parliament since 1985. In November 1992 he was elected to a second term as amir.

The Deputy Amir

Twice in its history the Jama‘at appointed a vice-amir (qa’im maqam amir), an interim measure to fill the vacancy left by an absent amir. More important has been the office of deputy amir (na’ib amir). Three deputy amirs were selected by the founding members of the Jama‘at in 1941, mainly to ensure that Mawdudi remained primus inter pares.[11] After two of them left the party in 1942, the office fell vacant, though the title was occasionally conferred on Islahi and Mian Tufayl to give them executive powers when Mawdudi was absent.

In 1976 the office was reintroduced with a new objective in mind. Three deputy amirs were appointed by the amir, and each was given a specific area of Jama‘at activities to oversee. The reintroduction of this office was part of the decentralization of power during Mian Tufayl’s tenure. It rationalized the Jama‘at’s organizational structure by dividing activities into separate units and delegating authority to the deputy amirs who oversaw those units. The office of deputy amir also gave the rising generation an important office to fill and brought the increasing number of peripheral activities and affiliated bodies under the party’s central command, both of which helped ease tensions within the party. The office exists only on a national level.

In 1987 the duties of the deputy amirs were formalized and their activities more clearly defined and given constitutional sanction by the shura’. Their number was increased to five. One is in charge of relations with other political parties; one is responsible for the Teachers Union and parliamentary affairs; one handles the operations of the Jama‘at’s central administration; one acts as a liaison with the Jama‘at’s student organization; and one is in charge of relations with ulama and other Islamic organizations. The office is by now an established part of the command structure.

The Shura’s

After the office of amir, the majlis-i shura’ is the most important pillar of the Jama‘at’s organizational structure. It has overseen the evolution and implementation of the party’s ideology and has controlled the working of its constitution. The lower-level shura’s replicate the functions of the central shura’, but they do not have the same importance as the central shura’. Members of shura’s at all levels are elected. Each represents a Jama‘at constituency geographically defined by the secretariat. These constituencies, drawn up by the Jama‘at’s election commissioner, coincide with national electoral districts whenever the numbers permit. A shura’ member must be a resident of his constituency.

In its early years the central shura’ had twelve members, but in anticipation of the Punjab elections of 1951 membership was increased to sixteen and as part of the constitutional reforms which followed Machchi Goth, to fifty.[12] That number was again increased to sixty in 1972, giving greater representation to members. In 1989 every central shura’ member represented approximately one hundred Jama‘at members. The increase in size has vested greater powers in the central shura’, while reducing the powers of each individual member, which was one reason why Mawdudi took the step in the first place following the Machchi Goth affair. With the same objective in mind, the Jama‘at’s constitution has kept the legislative power of the shura’ in check by giving the amir, deputy amirs, secretary-general, and provincial amirs, who attend shura’ sessions, voting rights. The number of these extra-shura’ votes is twelve, a fifth of the shura’ votes and a sixth of the total votes cast. In case of a tie the vote of the amir counts as two. Regular members of the Jama‘at may attend sessions of the shura’ with the permission of the amir, but have no speaking or voting rights.

The central shura’ meets once or twice a year and may in addition be called by the amir or a majority of its members whenever necessary. It reviews party activities and decides on future policies. It has ten subcommittees which specialize in various areas of the Jama‘at’s concern and provide the shura’ with policy positions. The central shura’ can probe the legal sources and determine the intent of Islamic law (ijtihad) when and if there exists no precedent for the ruling under consideration in religious sources. This enables it to decide on, as well as to clarify, doctrinal matters. While issues are openly debated in the shura’, verdicts are not handed down by majority vote alone. The shura’, especially when doctrinal matters are involved, works through a practice that reflects the Muslim ideal of consensus (ijma’). The majority must convince the minority of its wisdom, leaving no doubt regarding the course on which the Jama‘at will embark. In 1970 Mawdudi reported that in its twenty-nine years of activity, the central shura’ had given a majority opinion on only four occasions, the most notable of which was the prelude to Machchi Goth. Otherwise the central shura’ has, time after time, given unanimous verdicts.[13] Since Machchi Goth, many executive decisions have been put before the twenty-two-member majlis-i ‘amilah. This smaller council steers the Jama‘at through most of its activities when the central shura’ is not in session.

The Secretary-General and Secretariat

The day-to-day activities of the Jama‘at are overseen by the bureaucracy centered in the party’s secretariat. The office of the secretary-general (qayyim) was created in 1941. Since then, it has grown in power to become something akin to that of a party boss. The concept of a party worker was introduced to the Jama‘at in 1944 when the party set up special training camps in Pathankot for its personnel.[14] With the growth of the Jama‘at in size and the expansion of its activities, the workers have become an increasingly important element in the party. Between 1951, when the Jama‘at turned to politics, and 1989 the number of full-time workers rose from 125 to 7,583.[15] Since 1947 they have been controlled from Lahore by the secretary-general, who is appointed by the amir in consultation with the central shura’. Over the years, not only has the central secretariat increased in size but it has also reproduced itself at lower levels in the party, creating an administrative command structure which extends from the center to the smallest unit, paralleling the command structure controlled by the amirs.

The Jama‘at’s numerous publications are also controlled by the bureaucracy, the scope of the activities of which not only increases their hold on the Jama‘at but also gives them a say in the party’s political agenda. The importance of this bureaucracy was already evident early on, but it rose even farther as witnessed by the fact that both Mian Tufayl and Qazi Husain came to the office of amir directly from that of secretary-general. Members of the bureaucracy often are also members of shura’s of various units, augmenting the power of the central bureaucratic machine in the decision-making bodies of the party, precluding the kind of autonomy of the shura’ which led to the Machchi Goth affair.

In the 1970s, following its decisive defeat at the polls and with an amir at the helm who institutionalized the Jama‘at’s ideological zeal into distinct norms and procedures, the secretariat grew further in size, power, and number of workers. In 1979 a permanent training camp for workers was established at the Jama‘at’s headquarters in Lahore, and in 1980 alone 2,800 new workers went through that facility.[16] The Jama‘at’s considerable financial resources since the 1970s has permitted it to hire these workers and expand the activities of the bureaucratic force. All ordinary Jama‘at workers are paid for their services, but officers such as the amir, deputy amirs, or shura’ members are not paid, though they may serve in other salaried capacities in the party. Qazi Husain’s thriving family business in Peshawar has helped resolve the question of monetary compensation for his services. An increasing share of those joining the growing bureaucracy are alumni of Islami Jami‘at-i Tulabah (Islamic Society of Students), who are educated in modern subjects and have known each other since their university days. This further strengthens the position of the bureaucracy.

The bureaucratic structure of the Jama‘at is duplicated in the party’s burgeoning women’s wing (halqah-i khawatin), established in the 1950s. Some 70 percent of these women come from families where the men belong to the Jama‘at. They have no amir of their own, but have a central shura’ and an office of secretary-general (qayyimah). Their headquarters are situated in the central compound, from where the working of nazimahs (organizers) of lower-level units are supervised. The Jama‘at-i Islami women also have their own seminary, the Jami‘atu’l-Muhsinat (Society of the Virtuous), which trains women as preachers and religious teachers.

The women’s wing is primarily involved with propagating the Jama‘at’s literature and ideas among Pakistani women through its periodicals, the most important of which is Batul, and to incorporate Jama‘at families into the holy community by recruiting from among the wives and daughters of the Jama‘at’s members and by encouraging women to bring up their children true to the teachings of the Jama‘at.

The Jama‘at’s secretariat also oversees the working of special departments, the number and duties of which change depending on the needs of the party. In 1989–1990 they were the departments of finance, worker training, social services and welfare, theological institutions, press relations, elections, public affairs, parliamentary affairs, and Jama‘at organizational affairs. Each department is headed by a nazim (head or organizer), appointed by the amir. The departments are responsible to the secretary-general and at times to a deputy amir.

The increasing bureaucratization of the Jama‘at is clearly manifested in the central role of the party’s secretariat and workers in its headquarters compound, called Mansurah, on the outskirts of Lahore. To collect all members and votaries of the Jama‘at into a model holy community had been a central aim of the party since its creation. However, after its relatively short stay (1942–1947) in Pathankot, Jama‘at members had never again been able to gather in one location, though establishing a community/headquarters complex remained a goal. With funding through private donations, the land for the Mansurah compound was purchased in 1968, and construction on it began in 1972; the Jama‘at began to move its offices there in 1974. The complex has since grown to include a small residential community, where many Jama‘at leaders reside, and the central offices of the Jama‘at’s secretariat and some of its numerous affiliated bodies: the Islamic Studies Academy (Idarah-i Ma‘arif-i Islami), the Sayyid Mawdudi International Education Institute, Office of Adult Education, Bureau of the Voice of Islam (Idarah-i Sada-i Islam), the Arabic Translation Bureau, the Peasants’ Board (Kisan Board), the Ulama Academy, the Jami‘atu’l-Muhsinat, the offices of Jama‘at-i Islami of Punjab, schools, libraries, a mosque, and a hospital. In 1990, according to the election commission of Pakistan in Islamabad, Mansurah had some four thousand eligible voters.[17]

The Jama‘at’s organizational model—the amir, shura’, secretary-general, administrative, and command networks stretching from the top of the party to its smallest units—has proved so efficacious that it has become an example for others to emulate. The Jama‘at’s rivals, from ulama parties to Israr Ahmad’s Tanzim-i Islami and Tahiru’l-Qadri’s Minhaju’l-Qur’an, with some changes in titles and functions, have reproduced it in their own organizations as has the secular and ethnically based Muhajir Qaumi Mahaz (Muhajir National Front).

The size of the bureaucracy and the scope of its activities lead naturally to the question of the party’s finances. The Jama‘at’s total capital at its foundation was Rs. 74.[18] Its income at the end of 1942, mainly from the sale of books and literature, was Rs. 17,005.[19] This figure rose to Rs. 78,700 in 1947, and Rs. 198,714 in 1951, a tenfold increase in ten years.[20] By 1956 the annual budget for the Jama‘at-i Islami of Karachi alone stood at Rs. 200,000.[21] The Jama‘at’s income, from sale of books and hides (from animal sacrifices on ‘Idu’l-azha’), and increasingly from voluntary contributions and religious tax (zakat) payments by supporters and members, continued to grow at a steady pace throughout the 1950s and the 1960s (leaving aside confiscation of its funds on several occasions).[22] The purview of the Jama‘at’s activities, however, has grown at an equal, if not faster, rate than its income during the same period, ensuring a subsistence-level existence for the party. It was not until the 1970s that the fortunes of the Jama‘at took a turn for the better.

The rise to power of the left-leaning Bhutto in 1971, and the Jama‘at’s open opposition to him, brought new sources of financial support to its assistance. The Pakistani propertied elite, threatened by the nationalization policy of the People’s Party, the lower-middle class, whom Bhutto alienated with his socialist rhetoric and open display of moral laxity, and the Muhajir community, which began to feel the threat of Sindhi nationalism, all began to invest money in anti–People’s Party forces, one of the most prominent of which was the Jama‘at. The foreign governments—especially the monarchies of the Persian Gulf Trucial States, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia—wary of Pakistan’s turn to the left, also began supplying funds to forces which could provide an ideological brake on the spread of socialism and bog Bhutto down in domestic crises; again the Jama‘at became a major recipient of these contributions. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan a decade later merely increased the flow of funds from the Persian Gulf sources.

Jama‘at’s own connections with the Saudi ulama went a long way toward convincing the Persian Gulf donors of the wisdom of their policy and established the party as the main beneficiary of funds that Persian Gulf states earmarked for Islamic activities across the Muslim world. In fact, the Jama‘at’s ideological affinity with the Wahhabi Sunnis of the Persian Gulf states, Jama‘at’s earlier ties with Saudi authorities, and the party’s considerable reach across the Muslim world made it a convenient agent for the management of these funds and their distribution.[23] The Jama‘at’s international activities became increasingly intertwined with those of the Rabitah ‘Alam-i Islami (Muslim World Network), based in Riyadh, which oversees Saudi Arabia’s relations with various Islamic organizations from Mindanao to Morocco. The Jama‘at’s international influence grew in good measure through the aegis of the Rabitah. Saudi Arabia financed the establishment of a Jama‘at research institute in England, the Islamic Foundation, where the Jama‘at’s literature is published and disseminated in large quantities across the Muslim world. More recently, it has also projected the Jama‘at’s power internationally, most notably during the Rushdie affair.[24] Under the aegis of the Rabitah, ties with Jama‘at-i Islamis elsewhere in South Asia were strengthened, as were relations with other Islamic movements. The Rabitah also helped increase the Jama‘at’s leverage in its dealings with Pakistani governments, as numerous projects funded by Persian Gulf states in Pakistan, such as the International Islamic University in Islamabad, and the lucrative management of the flow of funds and arms to the Afghan Mujahidin, were opened to the Jama‘at. Financial patronage, however, has not been enough to control the Jama‘at: the party’s decision to support Iraq and its open derision of Saudi Arabia as a decadent lackey of American imperialism in the Persian Gulf war in 1990–1991 have greatly marred its relations with the Persian Gulf states and seriously affected their rapport.

The considerable rise in the number of Pakistani migrant workers in the Persian Gulf states since the 1970s also translated into larger voluntary contributions and zakat payments to the Jama‘at, as well as even closer ties between the party and the migrant workers’ hosts and employers in the Persian Gulf. Funds flowing into the Jama‘at’s coffers have also followed a recent increase in the number of Pakistani migrants to the West, many of whom are alumni of the student wing, the Islami Jami‘at-i Tulabah. These financial links and especially the rewards for stemming the tide of “Bhuttoism” in turn influenced the Jama‘at’s outlook on a number of issues. They made the party more staunchly anti-Bhutto and opposed to socialism in the 1970s than otherwise might have been the case, blinding it to the importance of populist politics in Pakistan. Antisocialist activism provided the Jama‘at with greater international renown and financial rewards, diverting the party’s attention from the realities of its political choices in Pakistan, especially after the fall of Bhutto. The free flow of funds also dampened the Jama‘at’s resolve, damaged its hard-earned discipline and morale, and gave the members a false, and ultimately ephemeral, sense of achievement and confidence. In a similar vein, these financial ties determined the Jama‘at’s stand on a host of religiopolitical issues, compromising the party’s autonomy of thought and action. The Persian Gulf connection, for instance, determined the party’s ideological and political response to other Islamic revival movements. A case in point was the strained relations between the Jama‘at and the Islamic Republic of Iran in the 1980s, which can, at least in part, be attributed to the Iran-Iraq war and the hardening of the policy toward Iran by the Persian Gulf states.

| • | • | • |

Affiliate Organizations

A host of affiliated semiautonomous institutions stand outside the Jama‘at’s official organization, but greatly extend the party’s reach and power. Despite their outwardly autonomous character, there is little doubt that the Jama‘at, to varying degrees, controls them. Although at first this was done for the sake of efficiency, in the end political considerations also played their part in the decision to relegate authority.

No sooner had the country of Pakistan been established than the Jama‘at was declared a pariah by its government, which also forbade its civil service—a primary target of the Jama‘at’s propaganda—to have any contact with them. The Jama‘at was compelled to set up institutions sufficiently distant to do its bidding without the fear of government retribution. During Ayub Khan’s regime the Jama‘at’s problems with the government were compounded when the party and everything associated with it were banned. The Jama‘at found it prudent to divest itself of some subsidiary organizations to guarantee their survival. One result was the establishment of Islamic Publications in Lahore in 1963, which has subsequently become the Jama‘at’s chief publisher in Pakistan. The Jama‘at had become so dependent on its publications as a source of revenue and as a means of expanding its power that the suppression of its publications during the early years of the Ayub Khan proved devastating. The new arrangement legally protected it from future government clampdowns on the party, thereby protecting its source of income and propaganda. Additional affiliate bodies were created in the 1970s to both protect and expand the party’s base of support.

The affiliate organizations fall into two categories: the first deal with propaganda and publications, and the second with political activities. Aside from Islamic Publications, there are other important affiliate bodies engaged in propaganda. The first of these is the Islamic Research Academy of Karachi, established in 1963 to counter the efforts of the Institute of Islamic Research, created in 1961 by Ayub Khan to propagate the regime’s modernist view of Islam. Shortly thereafter, the academy was directed to disseminate the Jama‘at’s views among the civil service. In the 1980s this task was mainly delegated to the Institute of Policy Studies of Islamabad, created, thanks to the pliant attitude of the Zia regime to Islamic activism, to serve as a “think tank” for Jama‘at’s policy makers. The Institute of Regional Studies of Peshawar and Institute of Educational Research (Idarah-i Ta‘lim’u Tahqiq) of Lahore also function in the same capacity, and outside Pakistan, the Islamic Foundation in Leicester, England, and the Islamic Foundation in Nairobi, Kenya, operate along similar lines. These institutions have done much to propagate the Jama‘at’s views and have contributed to the increasing influence of Islam across the Muslim world in general and in the social and political life of Pakistanis in particular.

Also important in this category of affiliate bodies are magazines which are not officially associated with the Jama‘at but are close to its ideological and political position. The most important of these are Chatan,Haftrozah Zindagi,Takbir,Qaumi Digest, and Urdu Digest. The Urdu Digest, first published in 1962, has extended the Jama‘at’s influence into the Pakistan armed forces, where it enjoys a certain popularity. All these publications print both social and political commentary and news analysis from Jama‘at’s perspective. The contribution of these ostensibly independent institutions to the dissemination of the Jama‘at’s views among the civil service, the military, and the political establishment has been substantial.

Affiliate institutions dealing with political matters are of even greater importance to the Jama‘at. For the most part they are unions which act both to propagate the Jama‘at’s views among specific social groups and to consolidate the Jama‘at’s power through union activity, especially among the new social groups that have been born of industrial change in Pakistan. Some of these unions, such as the Jama‘at’s semiautonomous student union, Islami Jami‘at-i Tulabah, were formed to proselytize but have since become effective politically as well. Others were launched in the late 1960s to combat the influence of leftist unions, and still others to expand the popular base of the Jama‘at following its defeat at the polls in December 1970. The most notable of these are the Pakistan Unions Forum, Pakistan Medical Association, Muslim Lawyers Federation, Pakistan Teachers Organization, Merchant’s Organization, National Labor Federation, Peasants’ Board, Pasban (Protector) Organization, Jami‘at-i Tulabah-i ‘Arabiyah (Society of Students of Arabic, which focuses on seminary students), and Islami Jami‘at Talibat (Islamic Society of Female Students).

Union membership runs the gamut of professions and classes in Pakistan from farmers and peasants to the educated middle class. The most important are the peasant, labor, and student unions. The Peasants’ Board was formed in 1976 to promote the Jama‘at’s views in the countryside and create a new voter pool for the Jama‘at to make up for the loss of voters in the elections of 1970. It was also part of the Jama‘at’s anti–People’s Party campaign, since it was meant to curtail the influence of the leftist peasants’ union, the Planters’ Association (Anjuman-i Kashtkaran) and to capitalize on opposition to Bhutto’s nationalization of agriculture in 1976. This dual objective informs the working of all Jama‘at unions. The Peasants’ Board has sought to lure the agricultural sector to the Jama‘at’s cause by remedying agricultural problems, but has thus far concerned itself only with the needs of small rural landowners and not the grievances of the more numerous landless laborers and peasants.

The National Labor Federation began its work in the 1950s but did not become prominent until the 1960s and the 1970s. It has the same objectives as the Peasants’ Board. The National Labor Federation and its subsidiary propaganda wing, the Toilers Movement (Tahrik-i Mihnat), were effective in countering some of the influence of the left among Pakistani laborers. In the late 1970s, with the weakening of the Bhutto government and rifts between the People’s Party and leftist forces, the National Labor Federation won important union elections at the Pakistan International Airlines, the shipyards, and Pakistan Railways and in the steel industry, causing consternation in Zia’s government. Soon after assuming power, Zia decided to ban all union activities, and the ban remained until 1988. Despite the National Labor Federation’s gains, the Jama‘at still has not learned to utilize its power base among the labor force effectively, because it is reluctant to engage in populist politics. Qazi Husain has promised his party to change that.

The National Labor Federation has served as a model and base for the expansion of the Jama‘at’s labor union activity. Since 1979 the party has formed white-collar unions among government clerical staff, which despite their small size have increased the Jama‘at’s control over the provincial and national civil service. For instance, in 1989 the clerical union at the University of Punjab was controlled by the Jama‘at, which allowed it to enforce a code of conduct, control curriculum and academic staff, and otherwise influence its running.

| • | • | • |

Islami Jami‘at-i Tulabah

The most important of the Jama‘at’s unions is the Islami Jami‘at-i Tulabah (IJT). Unlike the labor or the peasant unions, the IJT has no ideological justification. It does not galvanize support among any one social class. However, it has proved to be effective in battles against Jama‘at’s adversaries, it has diversified the party’s social base, and it has served as an effective means of infiltrating the Pakistani power structure. As the most important component of the Jama‘at’s organization, its workings and history both encapsulate and explain the place of organization in the Jama‘at and identify those factors which control continuity and change in its organization over time.

Central to contemporary Islamic revivalism is the role student organizations have in translating religious ideals into political power. The IJT, or the Jami‘at as it is popularly known, is one of the oldest movements of its kind and has in its own right been a significant and consequential force in Pakistani history and politics. In this capacity it has been central to the Islamization of Pakistan since 1947. It has served as a bulwark against the left and ethnic forces and has been active in national political movements such as those which brought down the Ayub Khan regime in 1969 and the Bhutto regime in 1977.

Origins and Early Development

The roots of IJT can be traced to Mawdudi’s address before the Muslim Anglo-Oriental College of Amritsar on February 22, 1940, in which, for the first time, he alluded to the need for a political strategy that would benefit from the activities of a “well-meaning” student organization.[25] Organizing Muslim students did not follow immediately, however. Not until 1945 did the Jama‘at begin to turn its attention to students. The nucleus organization was first established at the Islamiyah College of Lahore in 1945.[26] The movement gradually gained momentum and created a drive for a national organization on university campuses, especially in Punjab, that would support the party. The IJT was officially formed on December 23, 1947, in Lahore by twenty-five students, most of whom were sons of Jama‘at members,[27] and the newly formed organization held its very first meeting that same year. Other IJT cells were formed in other cities of Punjab, and notably in Karachi. It took IJT three to four years to consolidate these student cells into one organization centered in Karachi, and IJT’s constitution was not ratified until 1952.[28]

IJT was initially conceived as a missionary (da‘wah) movement, a voluntary expression of Islamic feelings among students, given shape by organizers dispatched by the Jama‘at. Its utility then lay in the influence it could have on the education of the future leaders of Pakistan, which would help implement Mawdudi’s “revolution from above.” IJT was at the time greatly concerned with attracting the best and the brightest, and it used the exemplary quality of its members—in education as well as in piety—as a way to gain acceptance and legitimacy and increase its following.[29] Although organized under the supervision of the Jama‘at, IJT was greatly influenced by the Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt, which its members learned about from Sa‘id Ramazan, a brotherhood member living in Karachi at the time. Between 1952 and 1955, Ramazan helped IJT leaders formalize an administrative structure and devise an organizational strategy. The most visible marks of the brotherhood’s influence are IJT’s “study circle” and all-night study sessions, both of which were means of indoctrinating new members and fostering organizational bonds.[30]

Initially IJT saw its primary concern as spreading religious propaganda on university campuses. In 1950 it launched its first journal, ‘Azm, in Urdu; it was soon followed by an English-language magazine, Student’s Voice, in 1951. IJT members were, however, as keenly interested in politics as in religious work. Hence, it was not long before they turned their attention to campus politics. Their involvement was not at the time an end in itself, but a means to check the growth of the Democratic Student Federation and the National Student Federation, the two left-wing student organizations on Pakistani campuses.[31]

Throughout the 1950s, opposition to the left became the party’s propelling force. It was on a par with Islamic consciousness, to the extent that the student organization’s view, in large measure, took shape in terms of its opposition to Marxism. All issues put before the students were soon boiled down to choices between antithetical and mutually exclusive absolutes, Islam and Marxism. Although this was a missionary attitude inferred from the Jama‘at’s doctrinal teachings, in the context of campus politics it controlled thought and, hence, action. The conflict between Islam and Marxism soon culminated in actual clashes between IJT and leftist students, confrontations that further radicalized the IJT and increased its interest in campus politics. Egg tossing gradually gave way to more serious clashes, especially in Karachi and Multan.[32] Antileftist student activism had become the IJT’s calling and increasingly determined its course of action. Once part of the Jama‘at’s holy community, it now began to look increasingly like a part of its political organization, hardly a source of comfort for the Jama‘at’s leaders, especially as between October 1952 and January 1953 leftist student groups clashed violently with police in the streets of Karachi, greatly radicalizing student politics. The tactics and organizational power of left-wing students in those months taught the IJT a lesson; it became more keenly interested in politics and began to organize more vigorously.

As radical politics spread in Karachi, the Jama‘at persuaded the IJT to temporarily move its operations elsewhere to keep it away from student politics.[33] From that point on, Lahore was its base of operations, and the IJT found a voice in Punjab, Pakistan’s most important province. It recruited in the numerous colleges in that city and across the province, which proved to be fertile. In Lahore, IJT leaders could also be more closely supervised by Jama‘at leaders, and as a result the students became more involved in religious discussions and education.[34] With increasing numbers of the organization’s directors elected from Punjab, in 1978–1979 the organization’s headquarters were permanently moved to Lahore.

Despite its moderating influence, the party proved unable to restrain the IJT’s drift toward political activism, especially after the anti-Ahmadi agitations of 1953–1954 pitted Islamic groups against the government. The Jama‘at had had a prominent role in the agitations and as a result had felt the brunt of the government’s crackdown. The IJT reacted strongly, especially after Mawdudi was tried for his part in the agitations by the government in 1954. The student organization had ceased to view itself merely as a training organization for future leaders of Pakistan; now it was a “soldiers brigade,” which would fight for Islam against its enemies—secularists and leftists—within the government as well as without. The pace of transformation from a holy community to a political organization was now faster in the IJT than in the Jama‘at itself. By 1955 Mawdudi had begun to be concerned with this new direction and the corrupting influence of politicization.[35] However, the Jama‘at’s own turn to political activism following Machchi Goth obviated the possibility of restraining the IJT’s political proclivities, and by the mid-1960s it had abandoned all attempts at checking the IJT’s growing political activism and was instead harnessing its energies. With the tacit approval of Mawdudi, the students became fully embroiled in campus politics and to an increasing extent in national politics.

Between 1962 and 1967, locked in battle with Ayub Khan, the Jama‘at diverted the students from confrontation with the left and from religious work to opposition to Ayub Khan and his modernist religious policies. They stirred up unrest on Pakistani campuses, initially to oppose the government’s attempt to reform higher education then to protest against the concessions made to India at the end of the Indo-Pakistan war of 1965. Their agitation led to clashes, arrests, and incarceration, which only served to institutionalize agitation—increasingly in lieu of religious work—as the predominant mode of organizational behavior; it also attested to the potency of student power.

Not surprisingly the IJT was pushed farther into the political limelight between 1969 and 1971 when the Ayub Khan regime collapsed and rivalry between the People’s Party and the secessionist Bengali party, the Awami League, resulted in civil war and the dismemberment of Pakistan. The IJT, with the encouragement of the government, became the main force behind the Jama‘at’s national campaign against the People’s Party in West Pakistan and the Awami League and Bengali secessionists in East Pakistan.[36] The campaign confirmed the IJT’s place in national politics, especially in May 1971, when the IJT joined the army’s counterinsurgency campaign in East Pakistan. With the help of the army the IJT organized two paramilitary units, called al-Badr and al-Shams, to fight the Bengali guerrillas. Most of al-Badr consisted of IJT members, who also galvanized support for the operation among the Muhajir community settled in East Pakistan.[37] Muti‘u’l-Rahman Nizami, the IJT’s nazim-i a‘la (supreme head or organizer) at the time, organized al-Badr and al-Shams from Dhaka University.[38] The IJT eventually paid dearly for its part in the civil war. During clashes with the Bengali guerrillas (the Mukti Bahini), numerous IJT members lost their lives. These numbers escalated further when scores were settled by Bengali nationalists after Dhaka fell.

The fights with the left in West Pakistan and the civil war in East Pakistan meant that the IJT’s penchant for radical action had clearly eclipsed its erstwhile commitment to religious work. The party’s attitude toward its student wing was, by and large, ambivalent. Although pleased with its political successes, the Jama‘at nevertheless mourned its loss of innocence. Yet, despite its trepidations, the party in the end proved reluctant to alter the IJT’s course, for the students were delivering tangible political gains to the party, which had little else to work with. While Mawdudi may have, on occasion, chastised student leaders for their excesses, other Jama‘at leaders such as Sayyid Munawwar Hasan (himself a one-time leader of the IJT) and Khurshid Ahmad (again a former IJT leader) were far more tolerant. They saw the political situation before the Jama‘at at the end of Ayub Khan’s rule and during the Bhutto period (1968–1977) in apocalyptic terms and felt that the end thoroughly justified the means. The IJT’s power and zeal, especially in terms of the manpower needed to wage demonstrations, agitate, and conduct electoral campaigns, were too valuable for the Jama‘at to forego. Political exigencies thenceforth would act only to perpetuate the Jama‘at’s ambivalence and expedite the IJT’s moral collapse.

The Jama‘at’s ideological perspective, central as it has been to the IJT, has failed to keep the student organization in check. The IJT and the Jama‘at have been tied together by Mawdudi’s works and their professed ideological perspective, and IJT members are rigorously indoctrinated in the Jama‘at’s ideology. Fidelity to the Jama‘at’s reading of Islam is the primary criterion for membership and for advancement in the IJT. Jama‘at’s ideology is indelibly imprinted on the IJT and shapes the student organization’s worldview. But as strong as discipline and ideological conformity are among the core of IJT’s official members, they are not steadfast guarantees of obedience to the writ of the Jama‘at. Most of the IJT’s power comes from its far more numerous supporters and workers, who are not as well trained in the Jama‘at’s ideology, nor as closely bound by the IJT’s discipline. In 1989, for instance, while the number of members and sympathizers stood at 2,400, the number of workers was 240,000.[39] The ability of the ideological link between the Jama‘at and the IJT to control the activities of the student organization is therefore tenuous. The political interests of the IJT often reflect the demands of its loosely affiliated periphery and can easily nudge the organization in independent directions; Nizami’s decision to throw the lot of the IJT in with martial rule in East Pakistan in 1971 is a case in point. In addition, organizational limitations have impeded the Jama‘at’s ability to cajole and subdue the IJT. The two are clearly separated by formal organizational boundaries, which create visible constraints in the chain of command between the them. Hence, while since 1976 a deputy amir of the Jama‘at has been assigned to supervise the IJT, his powers are limited to moral persuasion.[40]

The IJT grew more independent of the Jama‘at, and the party more dependent on the students, with the rise to power of Bhutto in 1971. The Jama‘at had been routed at the polls that year, while the IJT, fresh from a “patriotic struggle” in East Pakistan, had defeated the People’s Party’s student union, the People’s Student Federation, in a number of campus elections in Punjab, most notably in the University of Punjab elections, and had managed to sweep the various campuses of Karachi. The IJT’s victories breathed new life and hope into the dejected Jama‘at, whose anguish over the student organization’s conspicuous politicization gave way for now to admiration and awe. The IJT had “valiantly stood up” to the People’s Party and won, parrying Bhutto’s political power. The victory had, moreover, been interpreted to mean that Mawdudi’s ideas could win elections, even against the left. Following its victory, the IJT became a more suitable vehicle for launching anti–People’s Party campaigns than the Jama‘at, which as a defeated party was hard-pressed to assert itself. Unable to function as a mass-based party before the widely popular People’s Party, the Jama‘at increasingly pushed the IJT into the political limelight. The student organization soon became a de facto opposition party and began to define the parameters of its political control accordingly. When in August 1972 the people of Lahore became incensed over the kidnapping of local girls by Ghulam Mustafa Khar, the People’s Party governor of Punjab, for illicit purposes, they turned to the IJT. The organization obliged, raised the banner of protest, and secured the release of the girls by staging sizable demonstrations.[41] The IJT performed its role so effectively that it gained the recognition of the government. IJT leaders were among the first to be invited to negotiate with Bhutto later that year, once the People’s Party had decided to mollify the opposition.[42]

The IJT’s rambunctious style was a source of great concern to the People’s Party government. The student organization had not only served as the vehicle for implementing the Jama‘at’s political agenda but also was poised to take matters into its own hands and launch even more radical social action. While the Jama‘at advocated Islamic constitutionalism, the IJT had been advocating Islamic revolution. The tales of patriotic resistance and heroism in East Pakistan gave it an air of revolutionary romanticism. The myths and realities of the French student riots of 1968, which had found their way into the ambient culture of Pakistani students, provided a paradigm for student activism which helped the IJT articulate its role in national politics and to formulate a strategy for mobilizing popular dissent.[43]

The IJT thus became the mainstay of such anti-People’s Party agitational campaigns as the nonrecognition of Bangladesh (Bangladesh namanzur) movement of 1972–1974, the finality of prophecy (khatm-i nubuwwat) movement and the anti-Ahmadi controversy of 1974, and the Nizam-i Mustafa (Order of the Prophet) movement of 1977. As a result, the IJT found national recognition as a political party and a new measure of autonomy from the Jama‘at. The organization also developed a penchant for dissent, which given that it was an extraparliamentary force, could find expression only in street demonstrations and clashes with government forces. The IJT soon adapted well to militant dissent and proved to be a tenacious opponent of the People’s Party—a central actor in the anti-Bhutto national campaign that eventually led to the fall of the prime minister in 1977. Success in the political arena took the IJT to the zenith of its power, but it also restricted it to being a consummate political entity.

Following the coup of July 1977, the IJT continued on its course of political activism. It collaborated closely with the new regime in suppressing the People’s Party, used government patronage to cleanse Pakistani campuses of the left, and served as a check on the activities of a clandestine paramilitary organization associated with the People’s Party, al-Zulfiqar, in urban centers.[44] The IJT also played a critical role in mobilizing public opinion for the Afghan war, in which the organization itself participated wholeheartedly, producing seventy-two “martyrs” between 1980 and 1990.[45]

Political activism, therefore, contrary to expectations, escalated rather than abated during the Zia period. It had proved to be an irreversible process, an end in itself that became detached from the quest for an Islamic order. As a result, even though Pakistan was moving toward Islamization, the pace of political activism only increased. The students became embroiled in a new cycle of violence, fueled by rivalry with other student organizations.

Campus violence by and against the IJT and continuous assassinations, which claimed the lives of some eighty student leaders between 1982 and 1988, began to mar the heroic image which the IJT had when it was in opposition to Bhutto.[46] Violence became endemic to the organization and was soon directed against the IJT’s critics off campus.[47] The resulting “Kalashnikov culture,” efficacious as it had proved to be in waging political campaigns and intimidating opponents, was increasingly difficult for the Jama‘at either to control or to approve of. Nor was General Zia, determined to restore stability to Pakistan, willing to tolerate it.[48]

Despite pressures from Zia, the Jama‘at was unable to control its student group. Zia therefore proceeded to ban all student union activities in February 1984, which led to nationwide agitation by the IJT. Mian Tufayl (then amir), following pleas from the general, interceded with the IJT, counseling patience, but to no avail.[49] The IJT’s intransigence then began to interfere with the Jama‘at’s rapport with Zia and affect the party’s image. It was only when the IJT realized the extent of popular backlash against its activities, which translated into defeats in a number of campus elections between 1987 and 1991, that it desisted to some extent from violence on Pakistani campuses. The tempering of the IJT’s zeal was, however, merely a lull in the storm; the transformation of the student body into a militant political machine has progressed too far to be easily reversed.

Organizational Structure

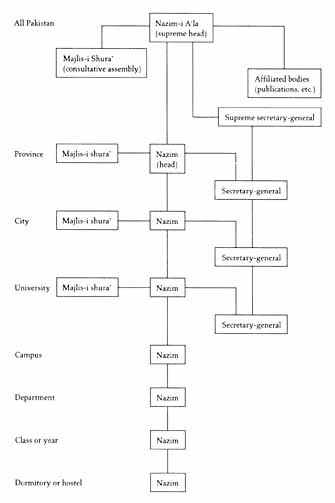

The IJT’s central organization is modeled after the Jama‘at’s. At the base of its organizational structure are the supporters (hami), loosely affiliated pro-IJT students; next come the workers (karkun), the backbone of the IJT’s organization and its most numerous category; the friends (rafiq); the candidates for membership (umidvar-i rukniyat); and finally, the members (arkan). Only members can occupy official positions; the most important office is the nazim-i a‘la (supreme head/organizer). The organizational structure at the top is replicated at lower levels, producing a set of concentric circles which extend from the lowest unit to the office of nazim-i a‘la. Each IJT unit has its own nazim (head or organizer) elected by IJT members of that unit (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Organizational structure of the Islami Jami‘at-i Tulabah

The first four layers of the IJT’s organizational structure have shura’s which are elected by IJT members of that unit. An IJT votary may participate in several elections for nazim or shura’ each year. For instance, he can vote in dormitory, campus, university, city, province, and national elections for nazim. The IJT’s activities and interorganization matters are supervised by the secretary-general (mu‘tamid-i a‘la), appointed by the nazim-i a‘la. Lower units of the IJT also have secretaries-general (mu‘tamids), who are selected by their respective nazims and the secretary-general of the higher unit. Each level of the IJT forms a self-contained unit and oversees the activities of the one below it. For instance, the command structure extends from the IJT’s national headquarters to the Punjab IJT, the Lahore IJT, the IJT of various universities in Lahore, the IJT of the campuses in each university, and finally the IJT of departments, classes, and dormitories in each university. On each campus, units monitor student affairs, campus politics, relations between the sexes, and the workings of university administration and faculty, at times acting as the de facto administrators of the university. The IJT regularly uses the university campus as its base of operations and utilizes university facilities such as auditoriums and buses for its purposes. Admission forms to the university are sold to applicants, generating revenue and control over the incoming students. The IJT uses strong-arm tactics to resolve the academic problems of its members or associates, provides university housing to them, and in some cases gains admission for them to the university.[50] The IJT also has subsidiary departments for international relations, the press, and publications which deal with specific areas of concern and operate out of IJT headquarters.

This organizational structure is duplicated in the IJT’s sister organization, the Islami Jami‘at Talibat (Islamic Society of Female Students), which was formed at Jama‘at’s instigation in Multan in September 1969. This organization works closely and in harmony with the IJT, extending the power of the latter over university campuses. Most Talibat members and sympathizers, much like the IJT’s founding members, come from families with Jama‘at or IJT affiliation. Their ties to the Talibat organization are therefore strong, and as a result the requirements of indoctrination and ideological education are less arduous.

The principal problem with the IJT’s organizational setup is an absence of continuity, a fault which is inherent in any organization with revolving membership. Because they must be students, members remain with the organization for comparatively short periods of time, and leaders have limited terms in office. The nazim-i a‘la and other nazims, for instance, hold office for one year and can be elected to that office only twice. Since 1947 only fifteen nazim a‘las have held that title for as long as two years. The organization has therefore been led by twenty-nine leaders in forty-four years. To alleviate the problems produced by lack of continuity, the IJT has vested greater powers in its secretariat, where bureaucratic momentum assures a modicum of organizational continuity. Also significant in creating organizational continuity has been the IJT’s regional and all-Pakistan conventions, which have been held regularly since 1948. These gatherings have given IJT members greater solidarity and an organizational identity.

All IJT associates from worker up attend training camps where they are indoctrinated in the Jama‘at’s ideological views and the IJT’s tactical methods. Acceptance into higher categories of organizational affiliation depends greatly on the degree of ideological conformity. To become a full-fledged member, candidates must read and be examined on a specific syllabus, consisting for the most part of Mawdudi’s works. All IJT associates are encouraged to collect funds for the organization through outside donations (i‘anat), which not only helps the IJT financially but also increases loyalty to the organization. Each nazim is charged with supervising the affairs of those in his unit as well as those in the subordinate units. IJT members and also candidates for membership meet regularly with their nazim, providing him with a diary known as “night and day” (ruz’u shab), in which every activity of the member or candidate for membership is recorded. The logbook details academic activities, religious study, time spent in prayers, and hours dedicated to IJT work. The book is monitored closely, and gives the IJT total control over the life of its associates from the rank of friend up to that of member.

The strict requirements for membership and advancement in the IJT have kept its membership limited. Yet organizational discipline has surmounted any limitations on the IJT’s ability effectively to project power. Its accomplishments are all the more astounding when the actual numbers of the core members responsible for the organization’s vital political role in the 1970s and the 1980s are taken into consideration (see table 2).

| Punjab | Lahore | Sind | Karachi | NWFP | Baluchistan | Total for Pakistan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Jama‘at-i Islami. | |||||||

| 1974 | |||||||

| Members | 82 | 20 | 62 | 40 | 25 | 6 | 175 |

| Friends | 881 | 150 | 676 | 350 | 270 | 65 | 1,892 |

| 1978 | |||||||

| Members | 134 | 38 | 102 | 80 | 41 | 10 | 287 |

| Friends | 762 | 106 | 584 | 425 | 233 | 56 | 1,635 |

| 1983 | |||||||

| Members | 236 | 34 | 131 | 90 | 63 | 20 | 450 |

| Friends | 1,588 | 190 | 553 | 417 | 284 | 75 | 2,500 |

| 1989 | |||||||

| Members | 274 | 42 | 200 | 110 | 100 | 10 | 584 |

| Friends | 844 | 129 | 616 | 339 | 308 | 30 | 1,800 |

| 1992 | |||||||

| Members | 256 | 50 | 143 | 107 | 106 | 8 | 414 |

| Friends | 2,654 | 314 | 1,260 | 1,403 | 657 | 64 | 3,698 |

The IJT has also extended its activity beyond the university campus. The circle of friends (halqah-i ahbab) has for a number of years served as a loosely organized IJT alumni association. The IJT has also more effectively extended its organizational reach into high schools, a policy initiated in the mid-1960s but which gathered momentum in the late 1970s, when the IJT reached the limits of its growth on university campuses. Further organizational expansion led the IJT to look to high schools for recruits and to reach the young before other student unions could. This strategy was particularly successful in universities where a large block of students came from particular regions through special quota systems. At the Engineering University of Lahore, for instance, the IJT was increasingly hard-pressed to compete with the ethnic appeal of the Pakhtun Student Federation for the support of students from the North-West Frontier Province. To solve the problem, in 1978–1979 it began recruitment in North-West Frontier Province high schools, creating a base of support among future students of the Engineering University before they arrived in Lahore, where they would come into contact with the Pakhtun Student Federation for the first time. The strategy was so effective that the Pakhtun Student Federation was compelled to copy it.

The IJT’s recruitment of high school students, a program they referred to as Bazm-i Paygham (celebration of the message), began in earnest in 1978. In the 1960s a program had existed for attracting high school students to the IJT, named Halqah-i Madaris (the school wing),[51] but the Bazm-i Paygham was a more concerted effort. Magazines spread the message among its young audience and promoted themes of organization and unity through neighborhood and high school clubs. The project was named after its main magazine, Bazm-i Paygham (circulation 20,000). Additional magazines cater to regional needs. In Punjab the magazine was Paygham Digest (circulation 22,000); in North-West Frontier Province, Mujahid (circulation 8,000); and in Sind, Sathi (circulation 14,000).[52] These journals emphasize not politics but religious education, so students can gain familiarity with the Jama‘at’s message and affinity with the IJT. Bazm-i Paygham has been immensely successful. Since 1983 the IJT has been recruiting exponentially more associates in high schools than in universities. The project has also benefited the Jama‘at; for many of those whom Bazm-i Paygham reaches in high schools never go to university and would not otherwise come into contact with the Jama‘at and its literature. More than a tactical ploy to extend the organizational reach of the IJT, this effort may prove to be a decisive means for expanding the social base of the Jama‘at and deepening the influence of the party on Pakistani society.

Although the IJT was modeled after the Jama‘at, it has transformed itself into a political organization at a much faster pace than the parent party. That the IJT relies more heavily on a periphery of supporters than the Jama‘at has sublimated its view of itself as a holy community in favor of a political organization to a greater extent. For that reason the IJT serves as a model for the Jama‘at’s development, and not vice versa.

While the Jama‘at’s membership has been drawn primarily from the urban lower-middle classes, the IJT has also drawn members from among small-town and rural people. Students from the rural areas are not only more keen on religious issues and more likely to identify with religious groups but are also more likely to be affected by the IJT’s operations on campuses than urban students are. The IJT controls university hostels and provides administrative and academic services, all of which are also more frequently used by rural and small-town students than by city dwellers. In essence, the IJT exercises a form of social control on campuses which brings these students into its orbit and under the Jama‘at’s influence.

The vagaries of Pakistani politics provide rural and small-town students with an incentive to follow the IJT’s lead. Religious parties—the Jama‘at is the most notable case in point—have since 1947 provided the only gateway for the middle and lower-middle classes, urban as well as rural, into the rigid and forbidding structure of Pakistani politics. Dominated by the landed gentry and the propertied elite through an intricate patronage system, political offices have generally remained closed to the lower classes. As a result, once attracted to political activism, rural, small-town, and urban lower-middle class youth flock to the ranks of the IJT in search of a place in national politics. The IJT’s social control on campuses is therefore reinforced by the organization’s promise of political enfranchisement to aspiring students.

A third of the current leaders of the Jama‘at began as members or affiliates of the IJT (see table 3). The IJT recruits in the ranks of the Jama‘at have created a block of voters in the party who bring with them close organizational bonds and a camaraderie born of years of student activism, and whose worldview, shaped by education in modern subjects and keenly attuned to politics, is at odds with that of the generation of ulama and traditional Muslim literati they will succeed. By virtue of the sheer weight of their numbers, IJT recruits are significantly influencing the Jama‘at and are improving organizational continuity between the Jama‘at and the IJT.

In the final analysis, the IJT has been a successful organization and a valuable political tool for the Jama‘at, though its very success eventually checked its growth and led the organization down the path to violence. Throughout the 1970s, the IJT seriously impaired the operation of a far larger mass party, the People’s Party, a feat accomplished by a small core of dedicated activists (see table 2). The lesson of this success was not lost on other small aspiring Pakistani parties, who also turned to student activism to gain political prominence. Nor did larger political organizations such as the People’s Party or the Muslim League, who had an interest in restricting entry into the political arena, remain oblivious to student politics as a weapon. They concluded that the menace of student activism could be confronted only by students. The Muslim Student Federation was revived by the Muslim League in 1985 with the specific aim of protecting that party’s government from the IJT. The resulting rivalries for the control of campuses, needless to add, has not benefited the educational system in Pakistan.

| Rank in the Jama‘at | Level of Affiliation with IJT | |

|---|---|---|

| Source: Office of the secretary-general of the Jama‘at-i Islami. | ||

| Qazi Husain Ahmad | Amir | Friend |

| Khurram Jah Murad | Deputy amir | Nazim-i a‘la |

| Khurshid Ahmad | Deputy amir | Nazim-i a‘la |

| Chaudhri Aslam Salimi | Secretary-general | Friend |

| Liaqat Baluch | Deputy secretary-general | Nazim-i a‘la |

| Hafiz Muhammad Idris | Deputy secretary-general[a] | Member/senior Member |

| Sayyid Munawwar Hasan | Amir of Karachi[b] | Nazim-i a‘la |

| ‘Abdu’l-Muhsin Shahin | Amir of Multan | Member |

| Shabbir Ahmad Khan | Amir of Peshawar | Member |

| Rashid Turabi | Amir of Azad Kashmir | Member |

| Amiru’’l-‘Azim | Director of information department | Member |

| Maqsud Ahmad | Secretary-general of Punjab | Member |

| ‘Abdu’l-Rahman Quraishi | Director of international affairs | Secretary-general of Sind |