Preferred Citation: LoRomer, David G. Merchants and Reform in Livorno, 1814-1868. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1987 1987. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9g5008z8/

| Merchants and Reform in Livorno 1814–1868David G. LoRomerUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1987 The Regents of the University of California |

To Morgan and Lucy LoRomer

Preferred Citation: LoRomer, David G. Merchants and Reform in Livorno, 1814-1868. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1987 1987. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft9g5008z8/

To Morgan and Lucy LoRomer

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In a study that began as a doctoral dissertation and that—in some real sense—has been living with me over the past fifteen years, a full list of acknowledgments is impossible. The assistance of some individuals, though, has remained impressive over the years, and to their names I must add some of more recent vintage.

First, I would like to thank the members of that original doctoral committee—Professor Richard Herr, Gene Brucker, and Neil Smelser—for their encouragement and critical suggestions. Earlier work at Berkeley with Professors Carl Schorske, Hans Rosenberg, and Richard Webster also assisted in my handling of this project. In Livorno I received the consistent help of Paolo Castignoli at the Archivio di Stato; of Bruna Palmati, Piero Brizzi, Luca Badaloni and the late Francesco Tarchi at the Biblioteca Labronica; and of Aldo Pratesi and his staff at the Livorno Chamber of Commerce. They helped make my frequent stays in the port city enjoyable and productive. My landlady, Margherita Nassi, with her inexhaustible quest for that extra mille lire did much to strengthen my language ability and to sharpen its polemical vigor. I must also acknowledge the generous assistance in Italy of Professors Carlo Corsini, Richard Goldthwaite, and Antonio Molho, as well as the encouragement of another

student of Livorno's economic and social history, Jean-Pierre Filippini. On his frequent trips to Florence, R. Burr Litchfield gave me the benefit of both his friendly encouragement and his detailed knowledge of Tuscan social history.

Without the help of these people—and without the material support of an Italian-American Research Fellowship from the University of California, Berkeley, and Faculty Research Grants from Michigan State University—this study would have been impossible to bring to completion. Needless to say, any flaws that remain are to be attributed only to me.

In addition to the individuals I have named, I would like to acknowledge the assistance—both personal and professional—that I have received from colleagues in East Lansing. Particularly encouraging over the years have been Richard White, Peter Vinten-Johansen, David T. Bailey, Harry Reed, and Peter Levine. Harold Marcus assisted with his blue pencil, William McCagg with his fertile imagination, and Mary Wren Bivins with a good critical reading of the final product and assistance with the illustrations. Geoff Eley at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, gave me the benefit of his knowledge of Gramsci and of the political process in nineteenth-century Europe. Antonio Calabria and Marion Miller offered me years of friendship and a rich understanding of Italian history. Finally, to my daughters Morgan and Lucy who have been with me over the course of this project and have brought me much happiness along the way, I would like to dedicate this book.

INTRODUCTION

This book examines the reform efforts of the merchant community in Livorno—the major port city of Tuscany—in the period from the restoration of the grand ducal government in 1814 to the abolition of the free-port status of the city in 1868. By its very nature, a study of reform must touch on many aspects of the city's economic and social life. I begin with an examination of the city's economy, ascertaining whether the port was in crisis or whether it had adjusted its activity to a new set of commercial circumstances. I shall examine the often one-sided views of contemporaries and later commentators before passing to an analysis of the more concrete data of commercial movements, changes in prices, and demographic shifts. The first section seeks to analyze some of the major elements that stimulated the reform movement and shaped its character.

The second section examines the structure of the merchant community, its economic and social values, and the institutions through which reforms were articulated and implemented. The third section concentrates on the economic reforms proposed by the merchant community to make Livorno more competitive with its rivals, particularly Genoa. The fourth section deals with the merchant community's efforts to spread its norms and values to the expanding lower-class

population of the city, thus forestalling social unrest and establishing a stable basis for future economic and political progress.

My fundamental task will be to evaluate the success or failure of the merchant reforms within the context of Livorno's social, economic, and political setting. The revolution of 1848 will mark the climax of the presentation. My aim here is not simply to add to the mass of data already available on the urban political movements important in the struggle for Italian independence and unity but to assess specifically the impact of the revolutionary turmoil on the merchant community's reform program. Ultimately, as we shall see, the revolution would strike that program a fatal blow.

Although interesting in its own right, a study of the reform program of Livorno's merchant community can clarify many issues regarding the economic, social, and political life of nineteenth-century Italy and Europe and can illuminate more specifically the contribution of the business elite to the Risorgimento. In the initial stages of the Risorgimento, at the end of the eighteenth century, publicists in Italy emphasized the economic dimensions of the national question because they sought economic development and because they wished to mobilize the support of businessmen and professionals. Massimo D'Azeglio's Programma per l'opinione nazionale italiana (1847) provides perhaps the most striking example of this effort.[1] The Piedmontese publicist and statesman sought to show his audience that the patriotic movement was composed primarily of reasonable and responsible individuals working to achieve a nation state and along with it free trade, the abolition of internal customs barriers, the facilitation of communications, and the establishment of a unified system of weights and measures.

D'Azeglio's emphasis on economic considerations proved congenial to a group of historians writing in the early decades of the present century who wished to break with the prevailing tendency to stress personal, political, diplomatic, and military aspects of the Risorgimento. In L'Origine del "Programma per l'opinione nazionale italiana," del 1847–1848 (1916), Raffaele Ciasca traced D'Azeglio's economic concerns to the

second half of the eighteenth century and demonstrated that his recommendations enjoyed wide support, particularly in the north.[2] In 1920, Giuseppe Prato, the dean of Risorgimento economic historians, argued in Fatti e dottrine economiche alla vigilia del 1848. L'Associazione Agraria Subalpina e Camillo Cavour that the central place of Piedmont and its prime minister in the national movement was due less to personal qualities and political considerations than to the level of progress achieved by Piedmontese society over the previous century.[3] In the interpretations of both D'Azeglio and Prato—and in others of a similar vein which followed—emphasis was placed not on ideology but on fact, not on political conspiracy and individual heroics but on a long-term process of reform. Only persistence and effective conditions could pave the way for Italian unification at a time when established regimes in the peninsula were easily capable of blocking any overt challenge to their authority.

Within the context of an economic interpretation of the Risorgimento, Marxism has provided a more specific theoretical focus that, as we shall see, continues to command wide respect in Livornese studies today.[4] For Marxist historians generally, the Italian liberation movement represents a classic instance of the successful efforts of a rising bourgeoisie to transform society according to its progressive economic interests. The growth of the European economy in the late eighteenth century and the impact of the French Revolution produced an Italian middle class able to manipulate the factors of production in a free-market economy. With the defeat of Napoleon and the end of French dominion in Italy, however, the peninsula returned to what was essentially a "feudal" stage of development in which authoritarian regimes maintained watchful control over chiefly patriarchal economic and social relations. The consequent struggle between the forces of reaction and progress led to the revolution of 1848, the war of 1859, and the ultimate triumph of the bourgeoisie.

Over the past several decades this general interpretation has been subject to mounting criticism. In a short article that appeared in 1952, Gino Luzzatto, a leading Italian economic historian, summarized the anti-Marxist position on the role

of economic factors in the Risorgimento.[5] First, he attacked the notion that the unification movement represented the product of a rising bourgeoisie looking to insure its progressive economic interests. Even on the eve of unification, Luzzatto argued, modern industrial sectors (steel and the metallurgical and mechanical industries) remained relatively undeveloped. Significant industrial production in foodstuffs and textiles was either geared largely to the export trade or was too modest to require a vast extension of the internal market. Ultimately, wrote Luzzatto, the economic argument for the Risorgimento was made not by businessmen, who possessed little felt need, but by publicists, who saw a tariff union and a national rail network as stimulants to future economic growth. It was they who perceived the giant strides being made elsewhere in Europe and who made urgent attempts to convince their more parochial compatriots to keep pace. Ironically, concluded Luzzatto, their arguments succeeded only too well, producing a pervasive pessimism in the late nineteenth century when the anticipated economic benefits of national unity failed to materialize.[6]

Luzzatto's views reflected the interpretation of one of the most significant monographs on the relationship of economic development and the Risorgimento, Kent Roberts Greenfield's Economics and Liberalism in the Risorgimento: A Study of Nationalism in Lombardy, 1814–1848 . Luzzatto pseudonymously translated this work into Italian in 1940, when Fascist racial policies prevented his continuing to teach in the Italian university system.[7] In releasing his volume in 1934, Greenfield declared that his chief purpose was "to give an impulse to non-political studies of the Risorgimento,"[8] and he registered his dissatisfaction with the fact that the Risorgimento was too often described in the ringing tones of idealism and as a series of "insurrectionary episodes."[9] Greenfield highlighted the underlying economic and social forces;[10] and he sought to replace the historiography of patriotism and sentiment with one that emphasized the relationships among economics, social institutions and habits, and the evolution of ideas.[11] He concluded that in the case of Lombardy, the

Marxist view that the Risorgimento represented the culmination of bourgeois class interests did not conform to the facts.[12]

Greenfield believed that Lombard patriotic philosophy eventually came to turn on the view that the progress of the region and the nation were dependent on the force that free capitalistic enterprise could exert in modernizing the peninsula.[13] The impetus, however, came not from a class-conscious bourgeoisie with strong economic interests to serve but from landed proprietors and intellectuals, many of whom were aristocrats. In effect, these publicists were not following the articulated interests of the bourgeoisie but were themselves attempting to rouse a timid and lethargic bourgeoisie to a consciousness of its interests.[14] According to Greenfield, Italian public opinion after 1848 would never again be governed successfully by the methods of the Old Regime, not because the material interests of the Italian community had been revolutionized but because the public now had a new conception of those interests.

Within the context of this vibrant and often polemical historiographical tradition, a study of Livorno and its merchant community can make a significant contribution. First, it can clarify the role of the business elite in the Italian Risorgimento, indicating the degree to which this group represented a progressive force working for political union and for the eventual emergence of a modern industrial economy. In his writing, Greenfield concluded that the Lombard merchants were fundamentally conservative and that the call for reform came from sectors of society other than the business elite. Steeped in the traditions of a predominantly agrarian community, merchants resented any interference with their traditional practices and were reluctant to strike out along new lines. They did not seek new markets for their products even when spurred by the government, and they continued to distrust credit not secured by property in land. Despite the often sarcastic urging of progressive publicists, the merchants remained largely passive in a changing world.[15] Similar criticism was voiced by publicists against merchants in the very different economic environment of Genoa, especially for their

reluctance to join together in modern forms of enterprise designed to improve the city's commercial situation and its tie to the hinterland.[16]

In an important study of the Venetian revolution of 1848, Paul Ginsborg has provided a more optimistic assessment of the reforming zeal of the Venetian middle class.[17] He has demonstrated the presence in both city and countryside of a group with considerable capital which was anxious to put an end to Venetian backwardness.[18] With the general revival of trade and commerce in the 1830s and early 1840s the activity of these landowners, businessmen, bankers, and members of Venice's Chamber of Commerce increased at a pace equal to that of the rise of their dissatisfaction with Austria's harsh fiscal policies, its excessive economic and political restrictions, and its lack of an effective social policy.[19]

Against Greenfield, Ginsborg has argued that despite the heterogeneous social character of this progressive group, it lay at the cutting edge of a bourgeois revolution. In the countryside the real distinction was not between noble and bourgeois landowners but between those who were trying to introduce more efficient and clearly capitalist methods and those who were not:[20]

The leaders of a revolutionary movement do not necessarily belong by origin to the class in whose interests the revolution is being made. Nor can or does the whole of that class reach the same level of consciousness and aspiration at the same time. All classes are uneven in composition and ideology, containing both backward and advanced elements. The northern Italian bourgeoisie of the 1830s and 1840s . . . was a class still very much in the process of formation. But within its ranks there existed highly ambitious sections and individuals . . . whose intentions were quite clear: to seek support for a movement that amounted essentially to "an attempt by the bourgeois to gain control of society.' The history of Venetia in the 1840s is the history of just such a group, composed primarily of a small number of businessmen and lawyers of the city of Venice. They appealed, with increasing clarity as the decade passed and conditions changed, to the commercial and landed interests in Venetian society, in the name of first economic and then political alternatives to the status quo.[21]

Nevertheless, Ginsborg suggests that the efforts of this group were fundamentally flawed. The failure of the urban bourgeoisie and its political supporters to make timely alliances with the peasantry was one of the major causes for the failure of the revolution.[22] Even on the national issue a number of merchants and businessmen remained averse to fusion with the other states of northern Italy—"They feared that with Milan the capital and Genoa the principal port of the new kingdom, Venice would be reduced 'to less than Chioggia.'"[23]

Clearly, traditional municipal sentiments were inhibiting attachment to the national ideal. Not surprisingly, therefore, the period after the failed revolution of 1848 witnessed a growing rapprochement between the Austrians and the wealthy elements of the Venetian bourgeoisie who had supported the revolution. When Venice finally became part of the Italian state in 1866, it was not the result of an armed insurrection but of the might of the Prussian army and the good offices of Napoleon III.[24] Bourgeois revolution or not, therefore, the efforts of the progressive elements of Venetian society were short-lived and ultimately ineffective.

This book will explore the degree to which such an assessment can also be applied to the merchant community in Livorno. More specifically, it will provide an analysis of the programs and underlying attitudes of the merchants in Livorno, the ways in which their efforts were shaped by the economic and social character of the free port, and the degree to which they contributed to more modern forms of economic and political life. As such, this work can also deepen our understanding and test the insights of the most influential interpretation of the Risorgimento to appear in postwar Italy, that of Antonio Gramsci.

In studies prepared during his active political career and while he was confined to a Fascist prison, Gramsci reflected on the political, moral, and intellectual foundations of Italian history. Two concepts in particular, hegemony and passive revolution , were fundamental to his interpretation of the Risorgimento.[25]Hegemony reflected the role of influence, leadership, and consent in the political process. Like many of

Gramsci's concepts, it is best considered in relation to its dialectical opposite, in this case domination . Whereas to Gramsci domination implied force and constraint, hegemony reflected the way in which one social group influenced other groups and responded to their needs so as to gain their consent for its leadership role in society at large.

While domination was exercised through the state (stato politico ), hegemony was as a rule transmitted through more decentralized agencies, which Gramsci associated with civil society (stato civile ). These agencies included labor unions, educational institutions, newspapers, charitable organizations, and representative assemblies, which were designed to foster a consensus on common, prevailing norms.[26] The relative strength of state and civil society, said Gramsci, varied from place to place, reflecting a society's level of development and—from Gramsci's perspective as a practical revolutionary—determining its vulnerability to challenge.[27] In Russia, for example, where "the State was everything" and "civil society was primordial and gelatinous," a frontal attack (in Gramsci's terminology, "a war of manoeuvre") could bring the whole edifice crashing to the ground; not so in the West, however, where "a proper relation between State and civil society" made for a "sturdy structure." In this case, "the State was only an outer ditch behind which there stood a powerful system of fortresses and earthworks," which constituted civil society.[28] To bring down such states, argued Gramsci, a "war of position" was more appropriate. Here one needed to systematically construct a series of counterditches and counter-fortifications—that is, to weaken the dominant hegemonic consensus by building a counterconsensus designed to erode society from within while preparing the way for a new social order.[29]

To Gramsci, passive revolution reflected a society's inability to achieve a full hegemonic relationship. He derived this concept from Vincenzo Cuoco, whose Saggio storico sulla rivoluzione napoletana del 1799 (originally published in 1801) had argued that the collapse of the Neapolitan Republic was the result of a mistaken effort to impose the principles of the French Revolution on a very different social environment.

The ideas of the Neapolitan revolution could have been popular had they been drawn from the depths of the nation. Drawn from a foreign constitution, they were far from ours; founded on maxims too abstract . . . they sought to legislate all the customs, caprices and at times all the defects of another people, who were far from our defects, caprices, and customs.[30]

In his essay Cuoco noted the enormous gap between the elite and the masses in the Neapolitan kingdom, and he suggested that the former had drawn its programs from foreign models that "offered nothing to the entire nation, which in turn scorned a culture which was not useful and which it did not understand."[31]

Like Cuoco, Gramsci saw passive revolution as revolution without mass participation. Unlike Cuoco, however, he condemned the elite not for endeavoring to implement the reforms of the French but rather for its failure to implement them effectively enough to win the support of the masses and to stem the tide of reaction. Indeed, Gramsci deeply admired the French Jacobins both for their incredible energy under pressure and for their successful efforts in forging a firm alliance between city and countryside.

Without the agrarian policy of the Jacobins, Paris would have had the Vendee[Vendée] at its very doors. . . . Rural France accepted the hegemony of Paris; in other words, it understood that in order definitively to destroy the old regime[régime] it had to make a bloc with the most advanced elements of the Third Estate, and not with the Girondin moderates. If it is true that the Jacobins "forced" its hand, it is also true that this always occurred in the direction of real historical development. For not only did they organise a bourgeois government—i.e., make the bourgeoisie the dominant class—they did more. They created the bourgeois State, made the bourgeoisie into the leading, hegemonic class of the nation, [and] in other words gave the new State a permanent basis and created the compact modern French nation.[32]

Gramsci also used the term passive revolution in a second way, with the meaning of a molecular social transformation that takes place beneath the surface of society in situations in

which the progressive class cannot operate openly.[33] He derived this perspective from the view of Karl Marx, as expressed in the preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy:

No social order ever disappears before all the productive forces, for which there is room in it, have been developed; and new higher relations of production never appear before the material conditions of their existence have matured in the womb of the old society. Therefore, mankind always takes up only such problems as it can solve.[34]

Gramsci saw in the survival of traditional economic and social institutions a basic characteristic of Italian history. In the late medieval and Renaissance periods, Gramsci noted, the urban corporate bourgeoisie failed to challenge the entrenched position of the feudal elites. Concentrating on its narrow corporate interests and operating in a cosmopolitan economic and political world, the bourgeoisie succeeded in amassing wealth and power but, notwithstanding the exhortations of Machiavelli, failed to forge the links with the countryside necessary for the achievement of a truly national society.[35] Similarly, in 1848 the radical Action Party, under the influence of Giuseppe Mazzini, failed to organize the urban and rural masses into a concerted attack on the forces of the old regime. In the immediate aftermath of the 1848 revolution, Camillo Cavour, the Piedmontese prime minister, absorbed disaffected members of the Catholic neo-Guelf movement into his own party and in molecular fashion incorporated the Action Party, so that in effect the masses were decapitated and not absorbed into the ambit of the new state.[36]

The history of Italy after formal unification continued this process. "Transformism" in the political life of the nation enabled the ruling class to coopt individuals but left the masses systematically excluded from effective political life.[37] The democratic reforms on the eve of World War I and the impact of the war and its aftermath shook the traditional political system. However, the rise of fascism and the erection

of a totalitarian state reimposed restraints on this process.[38] Nevertheless, Gramsci suggested, throughout Italian history changes had been occurring which progressively modified the preexisting composition of forces. In the nineteenth century, elements of the bourgeoisie had succeeded in creating an Italian state and achieving a level of capitalist development without revolutionary upheaval. Even under fascism, Gramsci noted, economic development continued, and there existed political forces that were working to erode the existing authoritarian order.[39]

Despite these gradual changes, however, Gramsci refused to abandon a revolutionary perspective. Passive revolution existed only dialectically; it was to be taken not as a call to defeatism but as a stimulus to a vigorous antithesis. One should not remain passive, Gramsci wrote, but should work to overcome the shortcomings of the Italian bourgeoisie, to incorporate the masses fully into the political system, and to create a truly national community. At the same time, one needed to take full account of the preexisting social and political forces so as to avoid a frontal attack when this could lead only to certain defeat.[40]

The study that follows is designed to explore Gramsci's interpretation of the Risorgimento in a particular regional context. Gramsci's concept of hegemony reflects the Livornese merchant community's reform impetus and its efforts to inculcate its norms and values in the masses. While Gramsci concentrated on the latter half of the nineteenth century, however, this study focuses on the first, indicating that hegemony had deep roots. It suggests that in Livorno the drive for hegemony was initially as vital but perhaps ultimately less successful than Gramsci supposed.

The process of political change in the city seems to conform to Gramsci's concept of passive revolution . The Livornese elite clearly worked to transform society in a bourgeois direction without provoking mass insurrection. The 1848 revolution, however, shattered this effort. And although a radical-democratic alternative also failed, as we shall see, the previous deferential patterns linking the city's elite and the masses would never be reconstituted. Ironically, during the ensuing

"decade of preparation" the Livornese moderates would find themselves on the margin of the political struggle. Shaken by the revolution, they would lose the desire for leadership and would allow effective political power to pass first to the central government in Florence and then, with the collapse of the grand ducal regime, to Piedmont.

The failure of the moderates in Livorno appears to support Gramsci's view of the inability of the elements of a potential ruling class throughout the peninsula to unite and contribute actively to the formation of the new Italian nation.

These nuclei existed indubitably, but their tendency to unite was extremely problematic; also, more importantly, they—each in its own sphere—were not "leading." The "leader" presupposes the "led," and who was "led" by these nuclei? These nuclei did not wish to "lead" anybody, i.e., they did not wish to concord their interests and aspirations with the interests and aspirations of other groups. They wished to "dominate" and not to "lead." Furthermore, they wanted their interests to dominate rather than their persons; in other words, they wanted a new force, independent of every compromise and condition, to become the arbiter of the Nation: this force was Piedmont and hence the function of the monarchy.[41]

Regrettably, Gramsci's view of the role of Piedmont (and his concept of Piedmontization ) has been generally ignored by commentators, which has hampered a full appreciation of his view of a failed bourgeois revolution in the peninsula.[42] To Gramsci the initiative of the Piedmontese state replaced that of the local elites and in effect extended the concept of passive revolution from the masses to a broad section of the elite.

This fact is of the greatest importance for the concept of "passive revolution"—the fact, that is, that what was involved was not a social group which "led" other groups, but a State which, even though it had limitations as a power, "led" the group which should have been "leading" and was able to put at the latter's disposal an army and a politico-diplomatic strength. . . . The important thing is to analyze more profoundly the significance of a "Piedmont" type function in passive revolutions—i.e., the fact

that a State replaces the local social groups in leading a struggle of renewal. It is one of the cases in which these groups have the function of "domination" without that of "leadership"; dictatorship without hegemony. The hegemony will be exercised by a part of the social group over the entire group, and not by the latter over other forces in order to give power to the movement, radicalise it, etc. on the "Jacobin" model.[43]

The failure of a truly organic solution to Italian unification represented a fatal flaw to Gramsci. True hegemony was never established, since state and civil society were not integrated. Italy's social elite failed to provide leadership and to respond to the needs and aspirations of the masses. Piedmont in the end exercised effective hegemony only over the elite, while over the rest of the country its position was largely one of dominance. Political ties were bureaucratic rather than democratic.

The morbid manifestations of bureaucratic centralism are the product of a deficiency of initiative and responsibility from below, that is of a political primitiveness of the forces on the periphery, even when they are homogenous with the hegemonic territorial group (phenomenon of Piedmontism in the first decades of Italian unity).[44]

The product of bureaucracy was "no unity but a stagnant swamp, on the surface calm and 'mute,' and no federation but a 'sack of potatoes,' i.e., a mechanical juxtaposition of single 'units' without any connection between them."[45]

[The authorities] said that they were aiming at the creation of a modern State in Italy, and they in fact produced a bastard. They aimed at stimulating the formation of an extensive and energetic ruling class, and they did not succeed; at integrating the people into the framework of the new State, and they did not succeed. The paltry political life from 1870 to 1900, the fundamental and endemic rebelliousness of the Italian popular classes, the narrow and stunted existence of a sceptical [sic ] and cowardly ruling stratum, these are all the consequences of that failure.[46]

Although characteristic of Gramsci's general ideas about the failure of the Italian unitary solution, Livorno's response was shaped by its particular situation, as we shall see. The city's free-port mentality, the shock of the 1848 revolution, the relative backwardness of central Italy, and the comparative indifference of the new Italian state to the city's problems would all hamper Livorno's full integration into the economic and political life of the nation. An examination of Livorno's history and its institutions, therefore, can help clarify the place of regional diversity and particular economic and social structures in the Italian Risorgimento. At the same time, it can reinforce a deeper understanding of those general patterns of strength and weakness which Gramsci saw as characterizing the process of Italian historical development fight up to the time of his imprisonment and untimely death.

The issues to be addressed here do not pertain only to the Italian peninsula, for questions on the nature of the middle class—its economic activities, social composition, political relationships, and culture—represent significant concerns in the historiography of early nineteenth-century Europe as a whole. This concern was underscored several years ago by the French economic historian Ernest Labrousse at the meeting of the Tenth International Congress of Historical Sciences in Florence.[47] In his report, Labrousse opposed abstract, generic definitions of the bourgeoisie and called for an investigation of its character, activities, and attitudes in specific settings. His charge echoed the work of historians which was already under way and helped to stimulate further research. This study is intended to make a modest contribution to that continued effort.

Before beginning, I will address a consideration that is fundamental to the interpretation to be set forth here. From the second half of the sixteenth century, when Livorno became a free port, the city's prosperity was based primarily on its ability to attract enterprising foreign merchants. The attraction was not expected to be permanent. Upon the merchants' retirements or whenever there was a worsening of the economic situation, the government anticipated that the merchants would return to their native states or would settle in

other, more comfortable locales. This tenuous relationship between the merchant community and the Tuscan state was reinforced by the city's privileges. As a free port, Livorno owed its prosperity to its extraterritorial status—that is, its position outside the normal schema of state taxes and regulations. Ironically, though, these very privileges reinforced the merchant community's detachment from the long-range concerns of the hinterland.

By the second half of the eighteenth century, I will suggest, this situation was changing, and Livorno's merchant community was becoming more involved in working for the long-term stability of the urban economy and in strengthening the relationship of the city and the hinterland. These efforts represent the initiation of a systematic reform program. In arguing for them, however, I wish to distance myself from a facile determinism that would link this growing involvement to the declining economic fortunes of the city and, more specifically, to the ending of its position as an international entrepot[entrepôt]. The economic changes in this period were far more complex. In addition, reform currents in the merchant community reflected a complex interplay of ideological considerations and institutional arrangements of a progressive and conservative bent: progressive, because the advocates of reform were interested in improving the economic and social life of the city to ameliorate the living situation of the city's masses, and conservative, because at the root of their efforts was the belief that only in this way could they counter the threat of social turbulence generated by the demographic pressure, economic uncertainties, and ideological ferment of the age. This situation and the response of the city's commercial elite were not unique to Livorno. For this reason, a clearer understanding of the reform movement in Livorno will allow us to better appreciate the anxieties and aspirations of European elites in that turbulent period that ushered in more modern forms of economic and political life.

PART ONE

THE ECONOMIC BACKGROUND

Chapter One

Patterns in Livorno's Commerce

Continuity, Change, Crisis

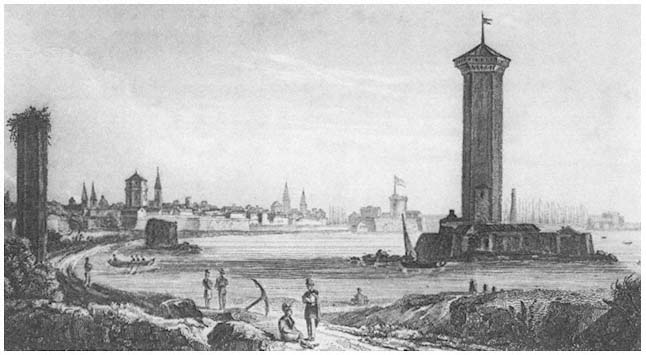

Both contemporary observers and recent studies agree that Livorno's commercial situation changed radically in the period following the wars of the French Revolution and the restoration of the grand ducal government in Tuscany. Previously, the city's prosperity had been based on its unchallenged ability to function as a free port of deposit open to the goods, ships, and merchants of all states. Commercial conditions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had favored the development of these ports. The difficulty of communication, the insecurity of the seas, and the modest carrying capacity of ships encouraged the establishment of free ports in convenient locations on the major trade routes, where commercial transactions could be handled easily and securely.

Livorno had been well endowed to prosper in this commercial situation. From the time of its absorption into the Florentine state in 1421—and especially during the two centuries of Medici rule—the city benefited from a series of provisions designed to encourage the settlement of foreign merchants and tradesmen in the area, to develop the city's commercial facilities, to establish the port as a privileged tariff zone, and to affirm its neutrality in disputes involving the major powers.

The basic provisions encouraging settlement in the area were promulgated by Ferdinand I in the 1590s.[1] In an attempt to foster the economic development of a region that was underpopulated and insalubrious, the state promised to provide houses, shops, and warehouses for those settling in the city, to prevent the imposition of guild restrictions, and, for a certain period, to waive tax assessments. In addition, for those willing to reside in the area, the state annulled all personal debts under 500 scudi and suspended previous penal condemnations, making exceptions only for the crimes of heresy, lese majesty, murder, and counterfeiting.[2] In the famous Livornina provision (10 June 1595) these fiscal and penal immunities were extended to religious minorities, especially Jews, who were in addition granted certain civic rights and freedom of residence and religion.[3]

Even though this provision was severely criticized during the nineteenth century for attracting undesirable elements to the city and for blackening its reputation, at the time of its enactment it did encourage population growth and the settling of a number of enterprising merchants in the area.

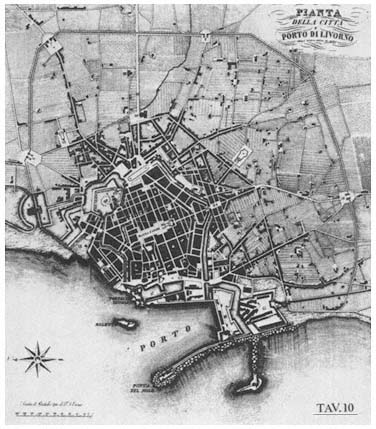

Due largely to the efforts of Cosimo I, Ferdinand I, and Cosimo II, Livorno acquired a port and storage and quarantine facilities, which made it among the best-equipped ports in the Mediterranean. Cosimo I completed work on a navigation canal linking Livorno and Pisa. Ferdinand I contributed the lazaretto of San Rocco for the purgation of ships arriving from areas that were sanitarily suspect and the pits (buche ) constructed throughout the city for the storage of grain. In 1611, Cosimo II ordered the construction of the wharf that bears his name. With its completion, the port of Livorno acquired the shape it would retain for more than two centuries.

The foundation of Livorno's prosperity as a free port, however, lay in its fiscal privileges. A series of piecemeal customs' reforms which began in 1451 culminated in a decree by Cosimo III (11 March 1675) abolishing the gabelles on most goods entering Livorno by sea and instituting in their place a small, fixed duty called the stallaggio .[4] Having paid this charge, a merchant could introduce his goods into the city

and sell, store, or refine them, then reexport them by sea without undergoing any further fiscal obligation. This provision provided the juridical basis for Livorno's existence as a free port.

The city's neutrality assured that its commercial activity would remain unharmed by the disputes of the great powers and that, if anything, it would benefit from them. First declared by Ferdinand II in a treaty with the French in 1646, Livorno's neutral status was confirmed by the great powers in 1691 and officially recognized in the treaty of 3 October 1735, which sanctioned the succession of the House of Lorraine to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. As the only port in the Tyrrhenian Sea which for most of the period could declare itself securely neutral, Livorno prospered particularly well during the times when war upset the commercial patterns of its rivals. In addition to taking over their commercial functions, Livorno was able to act as a marketplace for booty and to provision ships on both sides of a given conflict.[5]

Livorno's privileges enabled it to achieve a level of prosperity unknown to most other cities of the Italian peninsula. The centuries of its most rapid expansion paradoxically coincided with a period of economic and demographic stagnation in the rest of Tuscany. The city's commercial prosperity was clearly not predicated on the economic growth of the hinterland nor on the resourcefulness of an indigenous commercial elite.[6] The predominant activity of the port—the deposit and trans-shipment of merchandise—was handled primarily by foreign merchant companies or Jews, because only these two groups possessed the necessary capital resources and business contacts to succeed in commercial activity of this type. These merchants showed little interest in the marketing of Tuscan products or in the economic development of the Tuscan state.[7]

The fiscal privileges that Livorno enjoyed served to reinforce the city's detachment from the rest of Tuscany. Merchandise deposited in Livorno and transshipped out by sea was subject only to minimal stallage and port charges. However, merchandise that moved from Livorno into the internal market or, conversely, from the Tuscan hinterland into the port city was subject to the full duties of the Tuscan state.

While some commercial exchange did of course take place between Livorno and the Tuscan hinterland, in 1765 this direct, two-way commerce formed only a minimal part of the port's activity.[8]

Livorno's position in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, then, was exceptional. Both fiscally and economically the city remained detached from the Tuscan state, and the most important sector of its commerce was primarily in the hands of foreigners or Jews. Indeed, Livorno's facilities and privileges enabled it to prosper especially during those periods of dislocation when the Mediterranean world was beset by one or more of the principal scourges of the age—that is, plague, famine, and war. It was precisely at such times that the city's superb lazaretto facilities could guarantee the secure purgation of merchandise shipped from suspected areas, that its storage depots could ensure ample supplies of grain at a relatively stable price, and that its neutrality could guarantee that the port would remain open to the ships and goods of all states.[9]

After 1814, however, Livorno's traditional role as a free, neutral port seemed destined to provide a more tenuous foundation for its commercial prosperity. The period of relative peace following the wars of the revolution ended the special advantages that Livorno had derived from its neutral status.[10] The growing security of Mediterranean commerce coupled with the development of larger and faster ships and improved communications seemed to render free, deposit ports superfluous; the necessity to perceive the maximum profit on every commercial transaction made the expenses of transshipment undesirable.[11] Commercial transactions tended to become simpler everywhere as producers sought to establish direct links with consumers. In such a situation, the economic position of a given port would be increasingly forced to reflect the productive capacity of the state of which it formed a part. Because of the low productive capacity of the Tuscan economy during this period, the situation therefore did not offer bright prospects for Livorno's future prosperity.

The most succinct presentation of Livorno's position in the new commercial age was made in an article that appeared in

1837 in the prestigious Milanese journal Annali universali di statistica . . . .[12] It was understandable, the author noted, that those who predicted a brilliant commercial revival for Livorno should see it in terms of the reflorescence of a commerce of deposit, for the facilities that the city possessed for a commerce of this sort were such to make it preferred to all other ports in the Mediterranean. Unfortunately, he wrote, this type of commercial activity was by its very nature becoming less important every day. In an age of stiff competition and low profit margins, every effort was being made to rationalize business practices and eliminate unnecessary expenses. Commerce was tending toward its simplest expression, that is, to the direct exchange of merchandise between producer and consumer. All other parties were considered to be drones living at the expense of either one or the other of these and were eliminated from the commercial process whenever possible.

Livorno, the article's author noted, had already begun to suffer from these commercial changes. At one time the port had received colonial products from America and Holland and manufactured goods from England. In exchange for this merchandise the Levant would send its cottons, silks, and dyed cloths. Now, however, the English were going directly to Smyrna, Constantinople, and Alexandria to make their exchanges. They were carrying their sugar and salt products [salumi ] to Civitavecchia, "and they would go to the mouth of the Arno if they believed that they could sell a cargo there."[13]

It was highly unlikely, the author felt, that Livorno could develop its commercial ties with northern and central Italy to compensate for the loss of this commerce. In the eighteenth century, Lombardy, the Marches, Modena, and the Papal States had turned to Livorno for their colonial products and their dyed and manufactured goods. With the reopening of the free port in Trieste, however, the city had lost its markets in northern Italy and in much of the Papal States, for these regions could supply themselves more conveniently and cheaply there than in Livorno. Indeed, the author stressed, because the Apennines served to divide Livorno from the

plains of Lombardy the port could not hope to reassert its position in the transit trade. Geographic configurations would increasingly restrict Livorno's commercial range to Tuscany, Lucca, Massa, and Carrara. The few commissions still arriving from Modena, Bologna, and the Papal States were decreasing daily and would soon disappear altogether.[14]

Although the appearance of this article caused considerable stir, many of its points had been noted by members of Livorno's political and commercial elite long before the French Revolution, indicating that what appeared to be an incipient commercial crisis had deep roots. As early as 1758, in response to an inquest set up by the government, various spokesmen for the "nations" into which the merchant community of the city was then divided had stressed the decline of Livorno's commerce of deposit and transshipment and the growing tendency of producers to establish direct contacts with consumers.[15] The Jewish community reported that since 1748 the government of Naples had attempted to enter into direct commercial relations with Great Britain and the West by granting concessions to merchants willing to settle in that region. The policy had proved successful, with the result that much of the silk, grain, oil, fruit, and wine of Naples and Sicily were now passing directly to the West instead of going through Livorno. The French emphasized the growing spirit of enterprise and competition which was impelling states to handle their own commerce when possible instead of relying on foreigners. The auditor of the governor (Pierallini), in his Osservazioni sulla pace cogli Ottomani , stressed that the real decline in Livorno's role as intermediary occurred in 1748. In that year, in response to the peace treaty between Tuscany and the Ottomans, Livorno was placed under a stringent interdict by rival ports and had its traditional commercial patterns severely disrupted.[16]

Gloomy reports on the decline of Livorno's traditional commerce continued into the first half of the nineteenth century. A long, anonymous report in French sent to the Tuscan government in 1820 stressed again the decline of Livorno's commercial ties with Great Britain.[17] Traditionally, it said, Livorno had been the center of English commerce in Italy. With the

establishment of a general European peace, however, "this commercial protectorate, which had carried the prosperity of Livorno to the farthest limits, underwent several modifications." Feelings of rivalry toward the Continent encouraged Britain to use its maritime superiority to consolidate a firm commercial monopoly—"Its merchants wished to exploit directly, and by themselves, all branches of Mediterranean commerce which previously they had turned over to their factors." Other reports on the commerce of Livorno did not bother to discuss the reasons for the city's decline as a port of deposit, but simply took it as a given.[18]

Commentators corroborated another point made in the Annali di statistica , that the development of rival ports in the Italian peninsula was seriously weakening Livorno's hold over its traditional markets. In the inquest of 1758, Giuliano Ricci, a Tuscan merchant, noted that the mercantilist principles of the age were encouraging governments to channel commerce through their own ports. The Papal States were utilizing Civitavecchia or the recently established free port of Ancona, and Lombardy was establishing closer commercial ties with Venice.

In response to the same inquest, the Jewish community laid particular stress on the danger of Ancona, which, it said, derived its strength not so much from the facilities and privileges of its port as from its location. From Ancona one could ship goods to the major centers of northern and central Italy without having to repack them in smaller bundles, as was necessary in Livorno. The result was a considerable savings in time and money. In the first half of the nineteenth century, as we shall see, efforts were made to strengthen Livorno's ties with northern Italy. Evidence will suggest, however, that despite these attempts Livorno's transit commerce remained largely within the boundaries outlined in the Milanese journal.[19]

Although commentators agreed that Livorno could not hope to revive its commerce of deposit or even to preserve the majority of its markets in the Italian peninsula, many were unwilling to accept the commercial decline of the city as inevitable and believed that an expanding commerce in

Tuscan products could compensate the port for the loss of its traditional trade. In its report of 1758, the Italian nation (composed of merchants from the states of the Italian peninsula) had emphasized that with the growing competition from other ports it would be increasingly necessary to exploit the commercial possibilities of Tuscan agricultural and manufactured goods.[20] By 1830 this appeared to be taking place, for the gonfaloniere , the head of the municipal administration, proclaimed in his annual report that the marketing of Tuscan products had strengthened Livorno's commercial ties with other states and that it had "compensated us for the loss of traffic which previously was nourished by those foreign products of which the deposit has been lost."[21] The Giornale di commercio (Florence) noted in 1829 that although in a previous epoch Livorno's every resource had been based on its existence as a port of deposit, "it has become today the permanent and necessary vehicle for the export [sfogo ] of many indigenous products [produzioni territoriali ]."[22]

This belief in the fundamental shift in Livorno's commercial activity during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries has continued to the present and forms a basic tenet of recent studies on Livorno's commerce.[23] This is particularly evident in the work of Giorgio Mori, a historian who has had great influence in defining Livorno's social and economic position in this period. In an important article published in 1956,[24] Mori attempted to present a more concrete picture of Livorno's commerce in the early nineteenth century. To do so he restudied the statistics presented in 1837 by John Bowring to a parliamentary committee of the British House of Commons (see table 1).[25] On the basis of these statistics Mori concluded that of a total of 84,524,770 Tuscan lire (14,873,960 pezze) worth of merchandise imported into Livorno in 1835, only 19,346,000 lire (3,400,500 pezze)—or little more than 23 percent—was destined for deposit and successive reexport. The rest, he argued, was consumed in Livorno and the hinterland. To Mori these findings were of fundamental importance, for they indicated that "the nature of the port of Livorno and of its commercial emporium was radically changing in this period. Up until then it had been

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

substantially extraneous [estraneo ] to Tuscany. . . . From now on its wealth and its life would depend ever more on the wealth, life, and economy of the state at its back."[26]

Not considering for the moment whether an excess of imports is in itself evidence of the wealth and vitality of a state, it should be noted that Mori based his conclusions on a total misreading of Bowring's statistics. What Mori considered as merchandise imported into the city and deposited there for later reexportation was clearly not meant to be that at all. True, for reasons that will be explained shortly, Bowring used the term riesportazione to describe this merchandise in his final summary.[27] In the tables themselves, however, he called it varie manifatture e articoli d'esportazione .[28] That the latter is the more precise description appears evident in looking at the specific items, for nowhere to be found are the spices, cereals, or foreign manufactured goods that had traditionally been imported into Livorno for successive reexport. Instead, one finds olive oil, coral, tanned hides, pit carbon, boric acid, potash, marble, and so on—articles traditionally produced in Tuscany.

That Bowring resorted to the confusing use of the term riesportazione probably resulted from his desire to distinguish Tuscan products imported into Livorno (which, in terms of the tariff structure, stood outside the Tuscan state) for simple consumption from those imported into Livorno and held there for successive reexport. Such a distinction would be crucial in attempting to work out Livorno's balance of trade. Thus, in working out his final summary, Bowring subtracted this item from the import side of the ledger and considered it solely as an export.

The complexity of this analysis reflects Livorno's nebulous relationship to the Tuscan state. Nevertheless, when due allowance is made for this, the major categories in Bowring's statistics and what they tell us about the structure of Livorno's commerce in the mid-1830s become, I think, fairly clear. Read accurately, they show that of the imports the value of merchandise from abroad deposited in Livorno for successive reexport (4,699,500 pezze) totaled not 23 percent, as Mori supposed, but 41 percent. Of the exports, Tuscan products

(valued at 3,400,500 pezze) equaled 42 percent of the total, while the value of goods imported into Livorno and deposited there for successive reexport reached 4,699,500 pezze, or 58 percent of the total exports. Clearly, apart from indicating a real imbalance in Tuscan trade, these figures show that while direct, two-way commerce between Tuscany and other states was important, Livorno's traditional commerce of deposit and transshipment retained a dominant share of the city's commercial activity.

Another report helps to confirm this view. In 1838, Edoardo Mayer, director of Livorno's discount bank, prepared a long memorandum for Emanuele Repetti.[29] In his memorandum, Mayer indicated the final destination of many of the city's major imports. Of goods from the Levant (given an average annual value of 6,500,000 Tuscan lire), Egyptian raw cotton was reshipped in its entirety to manufacturing centers in Switzerland, England, France, and Belgium; two-thirds of the wool passed into France, England, and Piedmont; the silk not consumed in Tuscany was sent primarily to Genoa; wax and linens were consumed largely in Tuscany, though much of the former was marketed also in Sicily; gall nuts, saffron, and so on were reexported to England, Belgium, Holland, and Germany; and opium was reexported to England, France, and America. Of goods from the West and the North, salt fish (salumi ), metal, wood, pitch, tar, linens, and cowhides (valued at 6,750,000 lire) were consumed largely in Tuscany. Colonial products (valued at 9,500,000 lire) were consumed in Tuscany or shipped to other areas of the Italian peninsula. The most important single item that Mayer listed was manufactured goods from England, France, and Switzerland, to which he gave an average annual value of 23,000,000 lire. Only one-fourth of the manufactured goods imported into Livorno were consumed in Tuscany or in other parts of Italy; the remainder were reexported, primarily to the Levant.[30] Mayer concluded that "Livorno is a central point where, with a bustle of activity [con somma attivita[attività] ], products arriving by sea from opposite points are exchanged." Clearly, then, the city had not lost its character as an international emporium.

Regrettably, Mayer made no attempt in his report to assess

the final destination of cereals imported into the port (valued at 15,000,000 lire). Nevertheless, the report does possess the real merit of documenting the importance of a deposit trade in manufactured goods well into the nineteenth century. Table 2 shows that the volume of this trade remained important in the late 1840s. At the same time, however, this table illustrates the overwhelming predominance of another item in the city's commerce: cereals. Indeed, by the late 1840s (if

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

not earlier), cereals from the Black Sea seem to have become the single most important item in Livorno's commerce. This question merits further consideration.

Because of the destruction of the city's annual customs records and the lack of a complete statistical series on the port's commercial movement, tracing the growing importance of cereals in Livorno's commerce is hazardous, at best. One important indicator of this trend, certainly, can be seen in the repeated pleas of the merchant community for an expansion of the city's grain-storage facilities. The capacity of these facilities—both public and private—at the end of the eighteenth century was estimated at approximately 522,000 sacks.[31] In 1817, at the high point of the post-Napoleonic famine, the first requests were made to expand this capacity. In a letter to the secretary of finance, the governor of Livorno reported that comestibles were almost the sole staple of the city's commerce: grain and corn (biade ) were arriving daily; 400,000 to 500,000 sacks were already in deposit; and additional arrivals were imminent. The governor opposed the request of the chamber of commerce for the utilization of the lazarettos as grain-storage warehouses. However, he frantically searched the city for other possible storage depots.[32] During the 1820s the grain trade leveled off, and requests for additional facilities declined,[33] but the impetus picked up again in the late 1830s. The destruction of the old wall of the city in 1834 had eliminated many of the old ditches (fossi ) and pits (buche ) that had been located in or near it, and officials in charge of the government grain-storage warehouses and members of the chamber of commerce argued that new facilities would have to be constructed to replace them.[34]

Pressure on the government to this end increased in 1843 because of a growing fear of competition from rival ports. In his third quarterly report in that year, A. G. Mochi, the government commissioner appointed to oversee Livorno's discount bank, indicated that the grain trade was deserting Livorno for Marseilles. According to some, he said, this was because of the opinion that good storage facilities had been lost with the enlargement of the city and no new ones had been constructed to replace them. Giovanni Chelli, presi-

dent of the chamber of commerce, made a similar point and stressed that "it is absolutely necessary to demonstrate that we do not lack the necessary means . . . [and that] if some storage facilities have been destroyed, they have been replaced with new and better ones."[35]

Underlying these demands, it seems, lay the sense that the grain trade now formed the foundation of Livorno's commercial prosperity. In 1844, Carlo Bargagli, the captain of the port, stated succinctly that "the deposit of grain is today the principal branch of commerce in this city."[36] In 1845 the governor reechoed this sentiment in a report to the secretary of finance.[37] And in 1850 the chamber of commerce remarked more broadly that "experience had demonstrated that the city of Livorno is considered the principal cereal deposit of the Mediterranean."[38]

While they are revealing, reports of this sort are nevertheless fundamentally impressionistic. A more concrete sense of the relative importance of the grain trade in Livorno's commerce was provided by Mochi in several of his reports, in which he presented annual summaries of the value of goods (expressed in Tuscan lire and broken down into two categories, cereals and other merchandise) sold on the wholesale market (vendite di primo mano ) in Livorno. This material is summarized as shown in table 3.[39] Mochi admitted that his figures, drawn from Livorno's Giornale di commercio , were at best approximate.[40] However, at no point did he question their fundamental indication of the predominant value of grain sales. Indeed, his only comment on this point was to note that the disadvantageous position of other merchandise vis-a-vis[vis-à-vis] grain appeared less than many had supposed.[41]

The most concrete and dramatic evidence of the growing importance of grain in Livorno's commerce, though, can be found in some general summaries of the port's commercial movement. These summaries are reproduced in tables 2 through 9. They include the number of sailing ships arriving in the port as a raw annual aggregate and broken down according to their port of origin and the nature of their cargoes. The data are regrettably sparse. The summary of large

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

sailing ships arriving in the port is reasonably complete but provides no information on cargo or port of origin. This latter information is available in a complete annual series only from 1815 to 1826. Information for three years in the 1830s has been discovered and for only one—but an exceptional one—in the 1840s. None of these summaries by itself furnishes a complete picture of the grain trade in Livorno from 1815 to 1850. Taken together, however, they can provide a sense of the general profile of this trade and of its relative importance to other merchandise.

All these summaries document the massive movement of ships into Livorno during the two brief periods of famine (1815–1817 and 1847) which struck Europe during the first half of the nineteenth century. In both these periods the failure of the domestic harvest and the resulting increase in demand and soaring prices led the Tuscan government to temporarily suspend all charges on grain imports, which stimulated commercial activity in the port. Thus, in 1811, at the culmination of the French occupation of Tuscany, the number of large sailing ships entering Livorno had fallen to a low of 81 (table 4). By 1814—when Tuscany regained its independence—the number climbed to 422. In 1815 it jumped to 943, and in 1816 the number of arrivals peaked at 1,124.

A similar sharp increase is evident in the movement of

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ships from the Black Sea, which almost exclusively carried grain from the ports of southern Russia (see table 5). Here the number increased from 65 in 1815 to a peak of 195 in 1817. Finally, the arrival of ships in the port carrying grain climbed from 238 in 1815 to 398 in 1817 (see table 6). This last summary illustrates the relative importance of the grain trade at the climax of the post-Napoleonic famine. Of a total of 891 ships arriving in the port with merchandise in 1817, 398 (45%) were carrying grain.

A similar sharp increase in the movement of the port occurred in the famine year of 1847 (table 7). From 1846 to 1847 the arrival of large sailing ships jumped from 1,712 to 2,201. In 1848, as the result of a good harvest and the uncertainty of the political situation, arrivals dropped to 1,587, and in 1849 they fell still further, to 1,307. From figures provided by the customhouse one can obtain a sense of the relative importance of the grain trade in 1847 (table 2). Of the 2,501 arrivals noted in the customs records, the largest number by far (871 or 35% of the total) came from the Black Sea; 1,429 (57%) arrived with grain. From sixth place (8% of the total) in 1815, the Black Sea in 1847 had become Livorno's chief source of supplies. Grain cargoes arriving in the port in 1847 surpassed all other cargoes (including the large catchall category of "diverse merchandise") combined.

Between these two brief periods of famine the grain trade in Livorno was relatively less important. From 1818 well into the 1820s the commercial movement of the port slackened (table 5). In part, as commentators have pointed out, the decline was a result of disturbances in Levantine commerce caused by the revolution in Greece. It also reflected, however, a series of good harvests in Europe and, as we shall see shortly, the rigid tariff policies instituted by many European states to protect their agricultural producers. Thus, the number of large sailing ships arriving in Livorno with cargo dropped from a peak of 891 in 1817 to 682 in 1818 and reached a low of 501 in 1826 (table 7). An even sharper downturn is evident in the arrival of large sailing ships from ports in the Black Sea (table 5). The number of ships arriving with grain showed a similar drop, although with a much more erratic profile (table 6).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(table continued on next page)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

By the end of the 1820s, however, with the Greek question settled and more flexible tariff policies being instituted by European governments, the grain trade in Livorno had become stable and prosperous. This is evident from the follow-

ing list, which indicates the number of large sailing ships arriving in the port with grain from 1829 to 1836.[42]

|

Finally, summaries covering two periods from 1780 to 1789 and from 1816 to 1825 provide useful comparisons, since both cover periods of relative peace and security in the Mediterranean and include years of active trading and relative stagnation. Together, these summaries (presented in tables 8 and 9) graphically illustrate the fundamental expansion of Livorno's commerce with the Black Sea and testify to the growing predominance of the grain trade in the port.

The first summary, broken down by country of origin, not only testifies to the drop in commercial relations with Sicily and Malta (a fact that, as we have seen, was emphasized by many commentators) but also illustrates in detail the expansion of the city's contacts with the Black Sea. From 1780 to 1789 an average of only four ships a year (0.93% of the total arrivals) came from ports in the Black Sea, while in the decade from 1816 to 1825 the yearly average had jumped to 82 (12%). This was still below the average of 109 ships a year arriving from England and of 90 arriving from Egypt, many of which undoubtedly also carried grain. However, in rate of growth the Black Sea outclassed all other areas (1,950% versus 41%).

The second summary, broken down by cargo, shows that in the period from 1816 to 1825 the average number of ships arriving with cereals per year was superior to the number of ships carrying any other single product, and it also shows that the rate of growth for cereals from the first to the second decade was one and a half times greater than that of all other products combined.

The difficulties involved in using commercial statistics drawn from different sources and measuring different things are obvious. Not only do these statistics often confuse ships arriving in the port with and without cargo and occasionally

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

fail to clearly distinguish war and merchant ships but they also do not take into account that ships of the same type can differ greatly in tonnage. Value, moreover, does not at all necessarily follow from volume: a small cargo of spices is worth much more than a large cargo of grain or salt. Finally, as we shall see, a more active commerce does not necessarily indicate a more prosperous one. Crude as they are, however, these statistics do provide at least a rough indication of relative growth. Some reasons for this growth will be examined shortly. At present, it is sufficient to reaffirm that in the first half of the nineteenth century cereals had become a

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

predominant, if not the predominant, branch of Livorno's commerce.

What factors enabled a deposit trade in cereals to flourish at a time when, as we have seen, commentators were predicting the end of Livorno's traditional role as a port of deposit? Probably the most important single factor was the basic inability of the states of Western Europe to provide their expanding populations with domestic grain at moderate, stable prices. This inability, coupled with the availability of relatively cheap, high-quality Russian cereals, led European governments to eventually adopt more flexible policies toward the admission of foreign grain into their internal markets. These policies, as we shall see, would prove especially advantageous for a deposit trade in cereals.

Government policy toward the admission of foreign grain, however, had not always been flexible. The famine years of 1815–1817 had witnessed a tremendous influx of foreign—particularly Russian—grain into the markets of Western Europe, and once the crisis had ended governments had moved to erect controls to protect their domestic producers from competition with this cheap, high-quality product. England set the trend with its Corn Law of 1815, under the

provisions of which the importation of foreign cereals was prohibited when the price of grain on the domestic market fell below 80 shillings a quarter and was entirely free and unrestricted when the price exceeded that figure.[43] France imposed similar controls in 1819, permitting entry of foreign grain only if domestic prices rose, according to region, above 20, 18, or 16 francs per hectoliter. Prussia, Switzerland, Holland, Spain, and Portugal followed suit, setting up virtually prohibitive tariffs on cereal imports and waiving them only during periods of famine. These protectionist policies held sway in the 1820s, a period when the grain trade in Livorno was for the most part stagnant or in decline.

By the late 1820s, however, under pressure from consumers to stabilize the price of grain in their domestic markets, governments began to take a more flexible approach to the introduction of foreign cereals. In 1828, England provided the model once again by introducing a sliding-scale tariff for grain imports. Under its provisions a tariff of 23 shillings per quarter was levied on foreign grain when domestic prices reached 64 shillings; 16 shillings, 8 pence when the price reached 69 shillings; and I shilling when the price rose above 73 shillings.[44] Similar graded tariff systems were later adopted by Sweden (1830), France (1832), Belgium (1834), Holland (1835), and Portugal (1837).

It was no accident that the introduction of sliding scales coincided with the resurgence of the grain trade in Livorno, for these tariffs especially favored a deposit trade in cereals. For the maximum profit to be made under the new system, large amounts of grain had to be stored in ports near the great markets so as to be available promptly for taking advantage of passing opportunities. Thus, in 1833, after the introduction of the sliding scale in France, the price of wheat on the domestic market rose sufficiently to permit the importation of foreign grain. The effect on Livorno was immediate. Massive shipments to France over a two-month period depleted Livorno's grain deposits. Ships from the Black Sea that would normally have deposited their grain in Livorno were hurrying on to Marseilles to unload their cargoes under the low tariffs. As a result of these massive imports, however, the price of

grain was falling. Speculators in Livorno were predicting that the French market for foreign grain would soon close and that cereals would again reenter Livorno for storage until a new opportunity for their profitable sale presented itself.[45]

However, cereals deposited in Livorno not only supplied the demands of foreign states but also responded to the needs of the Grand Duchy itself. These needs were especially great in years of famine. Of the 702,565 sacks extracted from Livorno in 1815, for example, 507,059 passed into the Tuscan hinterland.[46] Of the 2,382,784 extracted in 1847, 1,914,028 passed into the hinterland.[47] Even normal years witnessed massive shipments from Livorno into Tuscany. O. Forni, a high-ranking member of the Tuscan customs administration, estimated that an average of 1,049,000 sacks of cereals were unloaded each year in Livorno and that of this total, 800,000 (roughly 80%) passed into the hinterland.[48] Luigi Serristori estimated that imports equaled about 13.3 percent of Tuscany's annual consumption of six million sacks, enough to feed its population for seven weeks and three days.[49] According to the administrator of the Royal Revenues, these imports were on the increase, reaching an annual average of 1,157,793 sacks in the five-year period from 1835 to 1839.[50]

Tuscany clearly was unable to feed itself. This had not always been the case. In the eighteenth century Tuscany had imported wheat only in times of famine, and in good years it had been able to export some of it.[51] The situation changed after the Napoleonic Wars. The disruption caused by war and the protracted fall in wheat prices in the 1820s coupled with the general unsuitability of the Tuscan terrain for intensive grain cultivation forced the state to rely increasingly on foreign grain to feed its expanding population.[52]

In this situation Russian cereals possessed distinct advantages on the free Tuscan market. As we shall see in more detail later, Russian grains were far less expensive than comparable products grown in Tuscany or the rest of Italy. Only Egypt could provide cheaper grain, but Egyptian wheat, subject to weevils and deterioration if exposed to dampness, traveled poorly and was more difficult to maintain in storage than its Russian counterpart. In addition, Egyptian

wheat was lighter in character (i.e., weight per volume) and was subject to sporadic export restrictions by the Egyptian government.[53]

Russian grain, moreover, was rich in gluten. This was especially important for hard wheat and indispensable for the manufacture of pasta, an important item in the Tuscan diet. Hard wheat could not be grown in Tuscany, and millers previously had imported it from Sicily. But Sicily could not supply the demand, and its commerce was periodically subject to vexing restrictions on grain exports. For these reasons, pasta makers in Tuscany increasingly came to rely on imported Russian grain, much of which was ground into flour at mills near Livorno.

Russian soft wheat also found great favor on the Tuscan market. Although some Tuscan soft wheat was better than the Russian, it was in short supply, was more expensive than Russian wheat, and was much demanded abroad—especially in England—for seed. Unknown to the Tuscan consumer, perhaps, Russian soft wheat was employed in the manufacture of even the finest bread. In December 1845 the British consul in Livorno reported to the Foreign Office that contrary to the reports of bakers, Tuscan soft wheat was probably not being used in the manufacture of prime-quality bread. "At the present prices," the consul said, "it could never suit the bakers to use it, as they profess to do, and the consumption in Livorno is known to be very limited." More likely, he felt, Russian and Polish were the types chiefly used, "the former because it is a wheat which yields an excellent result and the latter to impart whiteness."[54] Price, availability, and quality, then, served to give Russian grains a distinct advantage in the Tuscan market.

Periodically, tension was generated between the Tuscan government—which was concerned with maintaining its tax base and with protecting producers and consumers in the hinterland—and grain merchants in Livorno who were speculating on the Tuscan market. Grain speculators in Livorno, the secretary of finance remarked sarcastically in 1818, were quick to celebrate the outbreak of famine in the interior of Tuscany and correspondingly quick to lament the prosperity

of the local harvest and a drop in the price of grain, demanding in compensation that the government sacrifice the income it gained from its modest charge on the import of this product.[55] Save in periods of famine, the Tuscan government refused to modify its charges on grain imports and resolutely opposed attempts by the merchant community to transfer fiscal burdens from itself to consumers in the hinterland.[56]