Changing Patterns and the Development of New Regions

The simplest way to show what happened in California between, say, 1869, when Haraszthy left the state, and 1900, after a full generation of development had taken place, is by some statistics, graphically presented. A few details of graph 1 may be noted. The plateau from 1874 through 1877 conceals the fact that plantings increased mightily through those years—by an estimated 13,000 acres—so that the consequent overproduction destroyed prices. In 1876 grapes did not pay the cost of their picking, and many acres were uprooted or turned over to foraging animals. Through such drastic means, the industry had come back to a reasonably stable situation by 1880. The relatively small decline from 1886 to 1887 conceals another disastrous break in prices that year, which plunged the industry into a prolonged depression.

Accompanying the rising curve of production was another change, the rapid shift of dominance from south to north. Graph 2 comparing the San Francisco Bay counties to Los Angeles County will make this plain. The redistribution would be even more obvious if one took into account the continuing production of the Sierra foothill counties and the new production coming from the Central Valley counties. The reversal is clear enough, however; in the thirty years from 1860 to 1890, Los Angeles's share of the state's total sank from near two-thirds to less than a tenth; in the same span the Bay Area counties saw their share rise from little more than a tenth to near two-thirds, an almost symmetrical exchange.

The decline of the Southern Vineyard (as Los Angeles was called and as its

newspaper styled itself) was relatively sharp and quick. But that does not mean that winegrowing there disappeared, or was even much diminished to a casual eye. The news of phylloxera in Europe stimulated ambitious new planting, as we have seen in the case of Shorb and the San Gabriel Winery. Shorb's neighbor at the Santa Anita ranch, the Comstock millionaire E. J. "Lucky" Baldwin, built expansively in the late 1870s and early 1880s. He had 1,200 acres in vines in 1889, and promoted his Santa Anita Vineyard wines and brandies far and wide.[1] Another neighbor, L. J. Rose of the Sunny Slope Winery, tried, like Shorb, to exploit the opening created by phylloxera in European vineyards. Rose had been growing grapes and making wine for a decade when, in 1879, he determined on a great expansion. In that year he built what was called the largest and most modern winery in the state, with a capacity of 500,000 gallons to accommodate the yield of his 1,000 acres of vineyard. But the moment of the San Gabriel Valley's prosperity had passed for Rose as for Shorb. In 1887 Rose managed to sell the Sunny Slope Winery to a syndicate of English investors, who never recovered their money and whose experience considerably tarnished whatever appeal Los Angeles County winegrowing had as an investment.[2]

The onset of the Anaheim disease, which put an end to viticulture in Orange County, also helped to discourage the farmers of the San Gabriel Valley about the future of grapes and to turn them more and more to the all-conquering orange. Winegrowing in the south of the state therefore tended to shift eastwards to the region of Cucamonga, where viticulture was long established and the soil, a deep deposit of almost pure sand, was hardly suitable for anything else. When phylloxera appeared in California, this sandy soil protected the vines from the pest and so invited further plantings. Thus, the district, which had produced 48,000 gallons of wine in 1870, was producing 279,000 gallons in 1890.[3] It was here that Secondo Guasti, beginning in 1900, developed the "world's largest vineyard" (it ran to some 5,000 acres at its peak) and created a strong market for Cucamonga wine among the Italian communities of the East Coast..[4] The vineyards of the region persisted through Prohibition, depression, and war in the twentieth century, but fell victim at last to tract homes, freeways, airports, and industrial parks. Only rapidly diminishing vestiges survive in the 1980s.

Santa Barbara, Ventura, and San Diego counties all produced wine, but never very much—the total was 45,000 gallons in 1890, for example, and this was the work of scattered small producers. Nothing resembling an economically important industry ever arose in those counties, though there were some interesting enterprises. One of these was the Caire ranch on Santa Cruz Island, off Santa Barbara. The Frenchman Justinian Caire, a successful merchant in San Francisco, acquired the island around 1880; there, in addition to running sheep and cattle over the island's hills and valleys, he planted extensive vineyards and built a substantial winery of brick baked on the island. The island community was a varied mix of French, Indian, Mexican, Anglo, and Italian ranch hands and field workers. Wine-making was in the hands of French experts and the vineyards were tended by Ital-

1

Wine Production in California in Millions of Gallons, 1870-1900

Source: Report of the California State Board of Agriculture, 1911 (Sacramento, 1912)

ian workers, some of whom "spent their lives on the island and spoke no English." Among the hazards to viticulture on Santa Cruz were the wild pigs with which the island abounds. The vineyards included such varieties as Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Petite Sirah, and Zinfandel, and the wines acquired a good reputation, only to disappear, with so many others, under Prohibition..[5]

In San Diego County in 1883, through their El Cajon Land Company, a group of northern California wine men, including Charles Wetmore, Arpad Haraszthy, and George West, promoted the prospects of "viticulture and horticulture" on the

2

California Wine Production, North and South, 1860-90

Source: Report of the California State Board of Agriculture, 1911 (Sacramento, 1912)

27,000 acres of land they held for speculation..[6] Despite the high qualities claimed for Zinfandel wine grown in the county, winemaking was at best a sideline on San Diego ranches. There was, however, a considerable flurry of planting in San Diego following the collapse of the Anaheim region; the Italian investigator Guido Rossati reported that there were 6,000 acres in production in San Diego County in 1889, and 7,500 acres of vines not yet bearing..[7]

87

The Sunny Slope vineyard and winery of L. J. Rose in the San Gabriel Valley. With its thousand

acres of vines and half-million-gallon winery, this was one of the giants of the valley. It shared in

the general decline of the southern California vineyards, however, and after its sale to an English

syndicate in 1887 did not prosper. (Huntington Library)

88

A label of Justinian Caire's Santa Cruz Island Company, the only

wine producer on California's Channel Islands. (Author's collection)

A new development in the southern region was the growing of grapes for raisins rather than wine. Commercially successful trials with raisin grapes were made in Yolo County in 8867, but the great bulk of the trade soon shifted southwards. In 1873 raisin vineyards were set out in Riverside, in the El Cajon Valley of San Diego County, and along the Santa Ana River in Orange County, and these places soon became centers of raisin production..[8] The future lay with the region around Fresno, however, where planting also began in 1873 and where success was so rapid and complete that in barely more than a decade raisins were Fresno County's major crop. The raisin growers belong to the history of California winemaking because the grapes they grow have traditionally formed a part of the supply for the state's winemaking—rightly or wrongly. The mainstay of California raisin growing is the Thompson Seedless grape, introduced in 1872, which makes raisins of quality but at best a wine of entirely neutral flavor. Nevertheless, substantial tonnages of this grape in California have long been made into wine for blending or distilled into brandy for fortifying.

By 1870 the credibility of the idea that California was destined to be a great winegrowing country had been well established; it was also becoming clear that the southern part of the state had not succeeded in the essential matter of producing an attractive table wine: the combination of semidesert heat and the Mission grape stood in the way. A straw in the wind showing the new direction appeared in 1865, when the astute Charles Kohler of Los Angeles and Anaheim bought vineyards in Sonoma County. By 1870 he had "discovered" the Zinfandel, and from that time he planted his northern vineyards to it.[9] What Kohler was doing, and what Haraszthy and others had done before him, showed their opportunity to the smallholders and ranchers of the north. They had a reasonable selection of varieties, especially the Zinfandel, to replace the Mission grape, and these would yield acceptable dry wines from their more temperate valleys and hillsides. Anyone who possessed land not suited for irrigation or too rough for standard farming could put it into vines, as the newspapers, promotional agencies, and agricultural experts of the state were all urging everyone to do. The spirit of this time is expressed by Arpad Haraszthy, who had inherited his father's flair for publicity as well as his optimism, writing on "Wine-Making in California" in the Overland Monthly in 1872. The early winegrowers, he wrote, had not understood the importance of good varieties and proper soils, but that had now changed: "Every season brings us better wines, the product of some newly discovered locality, planted with choicer varieties of the grape, and entirely different from anything previously produced." Ultimately, he prophesied, California would produce a wine fit to take its place among the handful of the world's very finest..[10] All sorts of individuals and organizations were drawn into the work, and one can see several distinctive and clearly marked patterns taking shape in the 1870s.

First and most important was the individual farmer working on his own account and in his own style. More often than not the vine grower was also his own winemaker. Scores of the farm winery buildings put up at this time still stud the

towns and hillsides of the counties surrounding San Francisco Bay; typically they were simple, solid buildings, often of stone (or brick) or mixed stone and wood, providing a gravity-flow operation from upper to lower floor and a cool place of storage behind the stone walls of the lower stage.[11] A hand crusher and a hand press would suffice for the modest tonnage to be vinified, and the wines produced would perhaps go into vats and casks of native redwood—California's contribution to the medieval craft of the cooper, though not adopted as early as might be supposed.[12]

Many of the pioneering names of the 1850s continued to flourish: Jacob Gundlach in Sonoma, Charles Krug in Napa, and Charles Lefranc and Pierre Pellier in Santa Clara County, to name some of those whose wineries continue in operation to this day. To these pioneers, many new names were now added. Some of those still operating in California go back to this time, but very few indeed: Inglenook and Beringer in Napa County and Simi in Sonoma are notable; Cresta Blanca, Wente, and Concannon, all (originally) in the Livermore Valley, belong to the early 1880s, as do Geyser Peak and Italian Swiss Colony in Sonoma County and Chateau Montelena in Napa. The overwhelmingly greater number of the new establishments of this era were destined to briefer lives, and even the hardier of these could not survive Prohibition: Aguillon, Bolle, Cady, Chauvet, Cloverdale, Colson, Cralle, Delafield, Doma, Dry Creek, Eagle, Fischer, Glassell, Gobruegge, Green Oaks, Gunn, Hoist, Laurel Hill, Lehn, Live Oak, Meyer, Michaelson, Naud, Nouveau Médoc, Palmdale—such a list of vanished names might be extended into the hundreds.

There are no reliable statistics on the number of winemaking establishments in California in the nineteenth century. What is certain is that there was a rapid and unstable growth. The instability is well illustrated by the figures (perhaps approximately reliable) for the number of registered wineries in 1870 and 1880: in the first year there were 139 wineries; in the second, after the crash of 1876, only 45.[13] These figures must be for the more visible wineries only: the number of people actually making wine at any time was far greater. In the survey made by the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners in 1890, for example, 711 growers reported that they made wine, and even that figure is well below what must have been the case.[14] But whatever the actual number may have been, the point is that it kept going up and down.

The counties ringing San Francisco Bay, though they were clearly coming to dominate the industry, were not the only scenes of new development; the attraction to winegrowing was felt throughout the state wherever the chances seemed good. The expatriate Englishman (afterwards a prolific and exceedingly bad novelist) Horace Annesley Vachell put in a vineyard on the Coast Range in San Luis Obispo County in 1882, and viticulture on the Estrella Creek (or River) in that county went back a number of years earlier,[15] as it did in the town of San Luis Obispo itself, where, not long after 1859, Pierre Dallidet planted a vineyard and opened a winery.[16] In a few other counties that are now, in our time, coming to be

important in California winegrowing, only the barest of starts was made in the nineteenth century. In Mendocino County, for example, there were only two wine-makers listed in the state board's 1891 directory; the same source lists but two for Lake County, and for Monterey none at all, though there were some ten names listed as grape growers. The possibilities of the central coast of California, roughly between Monterey and Los Angeles, though not exactly unknown, lay unrecognized and undeveloped until very recent years. The fact is good evidence that the winegrowing map of California is far from its final form.

In an unsystematic way much was being learned about the possibilities of the vast number of soils, sites, and microclimates in California, but one can hardly say that the diverse regions of the state had been fully prospected. Nor have they been even today. It would not be anything like as soon as Arpad Haraszthy and others thought before the possibilities of the state's territories were sufficiently known to allow the right varieties of grape to be matched to the right soil and climate. That is a work that still has many years before it in California, to say nothing of the rest of the United States. But certainly much had been done in a rough-and-ready way by the end of the 1880s.

A new region, hitherto unattractive to settlement, begins to be heard from in the 1870s. The interior of the state, south of San Francisco and between Coast Range and Sierra, now the gigantic cotton, almond, tree fruit, and grape factory called the Central Valley, was then still pretty much what the Spaniards had called it, tierra incognita . Its main products for many years would be raisins and other fruit unfit to drink: the huge modern wine production of Kern, Tulare, Kings, Stanislaus, and Fresno counties lay in the future. But significant work had begun. And it was evident, from the beginning, that the growers of the Central Valley were going to make a lot of wine. Even if the bulk of the grapes they grew went to raisins, the scale of winemaking operations was much bigger here on an average than elsewhere.

Token plantings of grapes had been made in scattered parts of the Central Valley in the 1850s and 1860s, but the region was almost wholly given over to cattle grazing until the opening of the railroad through it at the beginning of the 1870s. Then speculators began to try what the possibilities of this virtually untouched territory might be. The center of development was the new town of Fresno, laid out in the middle of the valley and named by the Central California Railroad in 1872. An experiment in irrigated farming in that year produced sensational results on the Easterby ranch ouside Fresno, and the agricultural exploitation of the region was off and running. [17] The valley was hot and arid, but the touch of water seemed to release a magic fertility.

The honor of introducing the grape belongs, by all testimony, to Francis Eisen, a Swedish-born San Francisco businessman who had just bought property in Fresno County, and who put in vines to see what they might do. That was in 1873. These grapes, as a writer put it in 1884, turned out to be "the key which has unlocked nature's richest stores."[18] Eisen went on to develop his property on a scale

that was to be a model for agricultural development generally in the Central Valley: by the end of the seventies he had 160 acres in vines; in 1883 he had 200 acres; by 1888 he had 400, and his winery had been built up to a capacity of 300,000 gallons.[19] Eisen's original vine plantings had included raisin varieties as well as wine varieties, and it was the raisin that was to dominate Fresno County viticulture in the early days, as it does still. But winegrowing was established at the same time, and grew only less rapidly than the raisin trade. It is interesting to note that Eisen, in the untried Central Valley, experimented with a wide range of varieties, including a number of the American hybrids such as Lenoir, Cynthiana, and Norton.[20] The great object of the early Fresno growers was to find a way to prove that they could grow something other than sweet wines in the blazing heat of their valley, and the native American varieties were tried for the sake of their higher acids in blends with such vinifera as Zinfandel. It is also notable that the Mission was not part of the varietal mix in Fresno; its defects were now too well known to be doubted, and there was, by this time, no need to depend on it.[21]

Agriculture in the Central Valley was never an affair for the small proprietor. Only irrigated farming was possible, and the costs of preparation for that were too great for most individuals: the main irrigation works had first to be provided; then the ground had to be levelled, ditches dug, dikes and levees built, hedges planted, roads made—all before any planting went on. In these circumstances two kinds of proprietorship grew up. Either the land was developed by wealthy individual capitalists or corporations, or it was developed by the "colony" system, something on the model of the Anaheim scheme twenty years earlier. A group would form for the purpose of pooling its resources, buying land, and then dividing the property, to be paid for on long terms. The first of these was the Central California Colony in 1875. That was followed by a string of others—the Washington Colony, the Scandinavian Colony, the Fresno Colony, and, ominously, the Temperance Colony. Several of these associations had winegrowing as an object: the original Central California Colony, for instance. The Scandinavian Colony, founded in 1879, developed a considerable winery; it had a capacity of 100,000 gallons in the nineties, when it was taken over by the California Wine Association.[22]

The large-scale example set by the pioneer firm of Eisen was followed by a number of other Fresno vineyards and wineries. Among the most notable of these were the Eggers Vineyard, the St. George Vineyard, the Barton Vineyard, and the Fresno Vineyard Company. They may be dealt with briefly. The Barton Vineyard, founded in 1879, was the showplace of the region, splendid on a level of display that put it high among California attractions. Robert Barton, a former mining engineer, spared no expense to make his new property elegant and handsome in every detail: his fences, his hedges, his pleasure grounds, his winery, his barns, his mansion, his vineyards—all moved the admiration of the journalists who wrote about it: "a princely domain," one called it; "a paradise," said another.[23] Barton had five hundred acres of bearing vineyard by 1884, from which he made both dry and sweet wines from standard varieties such as Zinfandel and Burger; he also had a

89

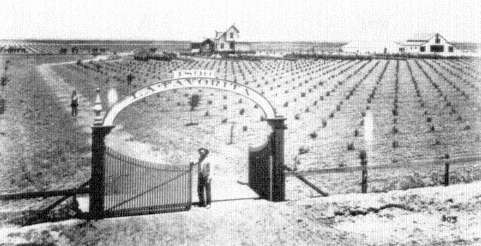

The bareness of the scene and the large scale of the operations that characterized Central Valley

winegrowing are both clearly evident here. (From Jerome D. Laval, As "Pop" Saw It [1975])

90

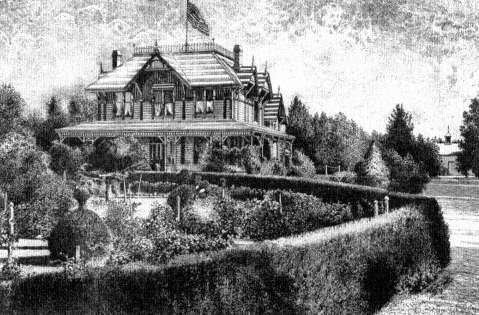

The Barton Estate Vineyard at Fresno, the unchallenged showplace of the Central Valley in

the pioneer days; founded in 1879, it was sold only eight years later to a syndicate of English

investors for $1 million. To contemporaries, the Barton Estate was "a princely domain" by contrast

to the bare flats of the valley around it. (From Frona Eunice Wait, Wines and Vines of California [1889])

mixture of other, more exotic varieties for trial, especially for sweet wines. In 1887, at the high point of English interest in California vineyard property, Barton sold his estate to a syndicate of English investors for a million dollars—a sensational transaction for Fresno, where winemaking was barely more than a decade old. Unlike the Sunny Slope Winery of L. J. Rose, which was sold to English investors at about the same time, the Barton Vineyard continued to grow; by 1896, as the Barton Estate Company Ltd., it had a capacity of half a million gallons, supplied by over 700 acres of vineyard. Its manager, installed by the English owners, was a Colonel Trevelyan, a survivor of the Charge of the Light Brigade.[24]

The other early wineries of Fresno had little notable about them apart from their tendency to grow to great size. The St. George Vineyard was the work of an immigrant Silesian named George Malter, who, like Robert Barton, had been a mining engineer before becoming a grape grower and winemaker, beginning in 1879. His vineyards covered 2,000 acres by the end of the century, and his winery was one of the largest in the state before Prohibition put an end to it.[25] The Eggers Vineyard and Winery, of 225,000-gallon capacity, was the property of a San Francisco land company that began vineyard development in 1882;[26] the Fresno Vineyard Company was also the work of a San Francisco corporation, in which the wine merchants Lachman & Jacobi had an original interest.[27] It was begun in 1880 and was soon developed to a capacity of 500,000 gallons. The Eggers Vineyard and the Fresno Vineyard Company were both essentially bulk wine producers, whose wines were shipped in volume to San Francisco and elsewhere to disappear into blends. All of these big Fresno district wineries were largely devoted to sweet wine production by the end of the century, though all had begun with a determination to make dry table wines. They failed to convince the skeptics that good dry wines could come from the heat of the Central Valley and were forced to turn to the production of vast quantities of anonymous sweet wine. This development was probably inevitable at the time: the production of good dry wines would not be possible until a much more scientific control, both of grape growing and of winemaking, had been worked out. Meantime, the growth of the Fresno vineyards went on. In 1908 there were 100,000 acres of grapes: 60 percent of this acreage was in raisin varieties, 38 percent in wine varieties, and 2 percent in table varieties. Acreage would go on increasing even after Prohibition.[28]

Perhaps the most highly regarded of the new regions exploited for vines around this time was the Livermore Valley in Alameda County, a pleasant region of oak-studded coastal hills a few miles inland from San Francisco Bay. Here an English sailor named Robert Livermore had made his way in 1844 and had set up as a rancher. He planted vines and made wine, but only, as most ranchers did, for his own needs.[29] The floor of the valley is a deep gravel bed, suited to the vine and not fit for much else; the valley, shut off from the Bay by the Berkeley hills, is hot, and yet, surprisingly, it has from the outset made good dry white wine, for many, many years a thing that the rest of California had trouble in producing. From a token 40 acres in the 1870s the valley's vineyards leaped to over 4,000 acres by

1884, a development largely owing to the promotional genius of Charles Wetmore, who invested in Livermore in 1882 and thereupon persuasively declaimed its virtues to a responsive state.[30] Livermore also profited from the fact that good varieties of the grape—notably the Semilion—were planted there in the first days of development. The region never had to pass through a phase of dependence on the Mission. It was, moreover, a region largely developed by wealthy men, as the glamorous names of their properties suggest: Chateau Bellevue, Olivina, Mont Rouge, Ravenswood, La Bocage. The small farmers did not lead here but followed.