Early Winegrowing in New Mexico

The earliest winemaking in the continental United States is credited to the Spaniards of Santa Elena, South Carolina, around 1568. The earliest successful viticulture and the oldest continuous tradition of winemaking, however, was established in the seventeenth century by the Spanish in those vast and barely populated regions of the Southwest that remained parts of the Spanish empire into the nineteenth century. Here the Jesuits and Franciscans planted grapes as they founded missions, and long before the days of Dufour, Adlum, and Longworth, the Spaniards and Indians of the widely scattered settlements from El Paso to the Pacific were drinking the wine of the country, though, to be sure, not a great deal of it. Even more important, this was wine from vinifera grapes, authentic wine as it had been known in Europe since the first apparition of Dionysus. In the dry, hot, stony soils of the Southwest the vine recognized something like its Mediterranean home and readily grew without suffering those afflictions of weather, disease, and insects that invariably devastated it in the East. All of this, however, went on invisibly so far as the United States was concerned. The great Spanish province of New Mexico, stretching from modern Texas to the Gulf of California, was wholly isolated from the developing country to the east; there was no line of' communication whatever between them, and foreign trade was forbidden in the Spanish possessions.

The first wine grapes in New Mexico were planted at the mission of Socorro, on the Rio Grande, by Franciscan missionaries about 1626;[1] the mission, abandoned in 1680 on the great Indian uprising of that year, has now vanished without

trace, but the valley of the Rio Grande has remained the site of a permanent viticulture. There is no record of the grape selected by the Franciscans in the earliest days; it may have been the same one they used later, the so-called Mission grape, grown wherever the missions might arise in order to provide wine for the celebration of the mass. This grape, so important in the history of wine in the Southwest, remains something of a mystery. It is, or is like, the grape called the Criolla in Mexico and in South America—"Creole," as we would say, meaning a New World scion of an Old World parent, adapted to the new conditions. The Criolla is not identified with any grape now known in Spain, though it must ultimately trace its origins to Spain; it is most likely a seedling of some Spanish variety brought over in the early days.[2] Whatever its origin, it is not well suited for making table wine, being too low in acid and without distinctive varietal character, so that its dry wines are fiat and dull. It was a good choice—or a lucky accident—for the early days, though, because it likes hot country, is very productive, and yields quite good sweet wines, much easier to preserve in difficult conditions than low-alcohol dry wines. The Mission is and will remain a significant grape in California for the production of sweet wines. Though one rarely or never sees the Mission grape identified on wine labels today, there were 1,800 acres of Mission vines in California in 1986, linking the modern industry to its origins.

Colonial New Mexico (including much of present-day west Texas and all of Arizona) remained Spanish until Mexican independence in 1821; not until that time was there any communication or commerce between this remote northern outpost of Spain in the New World and the United States. After 1821 the opening of the Santa Fe Trail brought Americans into the valley of the Rio Grande—the Rio del Norte as it was then commonly called—and reports of its grapes and wines began to make their way back to the East. Small vineyards were scattered along the hundreds of miles of the river from Bernallilo southwards, but there was no trade in wine. The New Mexicans had no transport, few wooden vessels, and even fewer bottles, so that the wine they made was strictly for local consumption. The methods of New Mexican viticulture were described in 1844 by Josiah Gregg, the historian of the Santa Fe Trail. The grape vines grew unsupported, and by being pruned back heavily were made to grow as low bushes; this allowed the grower to dispense with any complicated apparatus of posts and wires and trellises, and it also made it possible to cover the vines with earth in winter to protect them against freezing. For, though New Mexico is hot in summer, it lies high and dry and is subject to some sharp winter weather. From these low shrubs the Mexicans obtained "heavy crops of improved and superiorily-flavored grapes," as Gregg rather confusedly put it—though clearly he found them good.[3]

After the annexation of the New Mexico territory in 1848, making it supply the nation with wine was at least conceivable. As the young U.S. attorney of the territory, William Davis, wrote in 1853: "No climate in the world is better adapted to the vine than the middle and southern portions of New Mexico, and if there was a convenient market to induce an extensive cultivation of the grape, wine would

67

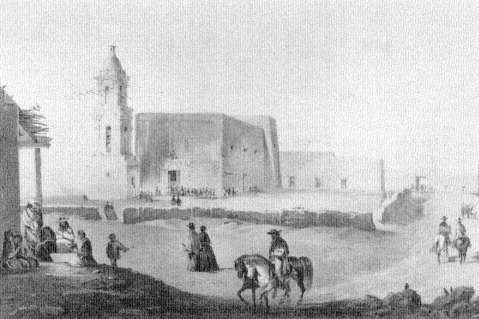

El Paso, Texas, whose "Pass wine" was known throughout the Southwest in the

ear of the Santa Fe Trail. This was the first region added to the United States in

which wine from vinifera grapes was produced. (From William H. Emory, Report

of the United States and Mexican Boundary Survey [1857])

soon become one of the staples of the country, which would be able to supply a large part of the demand in the United States."[4] The prospect was not necessarily illusory, but the history of New Mexico has not worked out that way. The production of wine in the state down to the most recent years cannot have been much greater than it was in colonial days. That is now changing, however, as New Mexico is currently the scene of large-scale investment—mostly of European money—in vineyards and wineries. It is far too early even to guess what the outcome of this sudden transformation of things will be, but it is particularly interesting as a renewal of winegrowing at one of its earliest sites in the United States.

Far to the south, at El Paso, where the Rio Grande comes out of the mountains to flow through a warm, low valley, winegrowing was extensive enough to support a trade and to acquire a reputation. The region—the American part of which is now in Texas—saw its first settlement in 1659, on the site of the present Mexican city of Juarez. Here orchards and vineyards flourished under irrigation; the vines, a Franciscan reported in 1744, "yield abundantly and produce fruit of good flavor and a rich wine in no way inferior to that of our Spain."[5] Early in the nineteenth century E1 Paso wine was the only revenue-producing crop in the whole province of Spanish New Mexico: "In no other country in America (so travelers declare) can wine be found with the taste and bouquet of the wine of New Mexico, especially

that produced in the large vineyards of E1 Paso del Norte. Its abundance is shown by its price, which is one real per pint, two hundred miles from the place where it is produced."[6] The reputation of El Paso wines was perpetuated by the Santa Fe traders, though one may doubt that they were very discriminating judges. "Pass Wine," they called it, and gave it preference over the wines produced closer to Santa Fe. E1 Paso brandy—aguardiente —was also famous, and perhaps even more in demand among the men of a trader's wagon train.

Most enthusiastic of all about E1 Paso wine was a young Missourian named John T. Hughes, a private in Colonel Alexander Doniphan's military expedition to New Mexico in 1846 who afterwards wrote a history of the affair. In that book, Hughes prints a copy of a letter that he was moved to send to the War Department after he had had a chance to look around him in the "fruitful valley of E1 Paso," where Doniphan's troops had arrived in December 1846:

The most important production of the valley is the Grape, from which are annually manufactured not less than two hundred thousand gallons of perhaps the richest and best wines in the world. This wine is worth two dollars per gallon, and constitutes the principal revenue of the city. Thus the wines of El Paso alone yield four hundred thousand dollars per annum. The El Paso wines are superior, in richness of flavor and pleasantness of taste, to anything of the kind I ever met with in the United States, and I doubt not that they are far superior to the best wines ever produced in the valley of the Rhine, or on the sunny hills of France.[7]

It was obvious to Hughes, and so he advised the War Department, that an energetic American population should displace the languid Mexicans; production of wine would then increase tenfold, and a link—road, railroad, or canal—between the valley and the United States would take the wine to a ready market. Hughes favored the plan of canalizing the Rio Grande from the Gulf to the falls at E1 Paso.[8] What answer the War Department made we do not know. No canal was dug, and the vineyards of E1 Paso seem to have declined through the rest of the nineteenth century under gringo auspices. When the Patent Office's viticultural explorer H. C. Williams arrived in the valley in 1858, he found that very few vineyards had been established on the American side of the river, and that the production of the whole region was declining.[9] There were then three qualities of wine produced by the El Paso vintners: a first-quality light red wine; a second-quality darker wine, the one properly called "Pass Wine"; and a third-quality wine left to the poor.[10] Here is how Williams described the methods of production he found in E1 Paso:

An ox hide is formed into a pouch, which is attached to two pieces of timber and laid on two poles supported by forks planted in the ground-floor of the room in which the vintage takes place. The grapes are gathered in a very careless manner, and placed in the pouch until it is filled. They are then mashed by trampling with the feet. In this condition the mashed fruit, stems, and some leaves remain until fermentation takes place, which requires from fifteen to twenty days. An incision is made in the lower part of the pouch, through which the wine drips; it is transferred to barrels. The wine now

has a flat, sourish taste. Should it be desired to make sweet wine, grape syrup, made by evaporating fresh juice, is added until the wine has the desired sweetness. It is not afterwards fined, or racked off, but remains in the cask until used.[11]

It was just this pastoral simplicity that so annoyed the Americans who observed winemaking in E1 Paso. Colonel William Emory, who conducted the official survey of the Mexican-American border, saw the neglected potential with exasperation. He had, he wrote in his official Report , drunk wine in El Paso "which compared favorably with the richest Burgundy." But there was no control and so no consistency—the next wine might well be "scarcely fit to drink." The promise was great, for, he wrote, "in no part of the world does this luscious fruit flourish with greater luxuriance than in these regions, when properly cultivated." The reason that nothing adequate to develop the promise had been done was, in the colonel's judgment, quite simple:

No one of sufficient intelligence and capital, to do justice to the magnificent fruit of the country, has yet undertaken its manufacture. As at present made, there is no system followed, no ingenuity in mechanical contrivance practised, and none of those facilities exist which are usual and necessary in the manufacture of wine on a large scale.[12]

Despite the optimistic views of writers like Hughes, Williams, and Emory, the Americans never took hold of the chance to develop the winegrowing of the Rio Grande Valley. There were reasons enough for this state of affairs: the isolated, underpopulated character of the region, the imperfect harmony between the Mexican-Indian cuisine and wine (compare the relative unimportance of wine in Mexico itself); and most of all, no doubt, the quick growth of California and its wine industry within a few years of the transfer of New Mexico to the United States. The situation is now undergoing a rapid and dramatic change, and the development of winegrowing in Texas and New Mexico will be one of the most interesting ventures in the history of American wine in this decade.