PART 3

THE DEVELOPMENT OF CALIFORNIA

9

The Southwest and California

Early Winegrowing in New Mexico

The earliest winemaking in the continental United States is credited to the Spaniards of Santa Elena, South Carolina, around 1568. The earliest successful viticulture and the oldest continuous tradition of winemaking, however, was established in the seventeenth century by the Spanish in those vast and barely populated regions of the Southwest that remained parts of the Spanish empire into the nineteenth century. Here the Jesuits and Franciscans planted grapes as they founded missions, and long before the days of Dufour, Adlum, and Longworth, the Spaniards and Indians of the widely scattered settlements from El Paso to the Pacific were drinking the wine of the country, though, to be sure, not a great deal of it. Even more important, this was wine from vinifera grapes, authentic wine as it had been known in Europe since the first apparition of Dionysus. In the dry, hot, stony soils of the Southwest the vine recognized something like its Mediterranean home and readily grew without suffering those afflictions of weather, disease, and insects that invariably devastated it in the East. All of this, however, went on invisibly so far as the United States was concerned. The great Spanish province of New Mexico, stretching from modern Texas to the Gulf of California, was wholly isolated from the developing country to the east; there was no line of' communication whatever between them, and foreign trade was forbidden in the Spanish possessions.

The first wine grapes in New Mexico were planted at the mission of Socorro, on the Rio Grande, by Franciscan missionaries about 1626;[1] the mission, abandoned in 1680 on the great Indian uprising of that year, has now vanished without

trace, but the valley of the Rio Grande has remained the site of a permanent viticulture. There is no record of the grape selected by the Franciscans in the earliest days; it may have been the same one they used later, the so-called Mission grape, grown wherever the missions might arise in order to provide wine for the celebration of the mass. This grape, so important in the history of wine in the Southwest, remains something of a mystery. It is, or is like, the grape called the Criolla in Mexico and in South America—"Creole," as we would say, meaning a New World scion of an Old World parent, adapted to the new conditions. The Criolla is not identified with any grape now known in Spain, though it must ultimately trace its origins to Spain; it is most likely a seedling of some Spanish variety brought over in the early days.[2] Whatever its origin, it is not well suited for making table wine, being too low in acid and without distinctive varietal character, so that its dry wines are fiat and dull. It was a good choice—or a lucky accident—for the early days, though, because it likes hot country, is very productive, and yields quite good sweet wines, much easier to preserve in difficult conditions than low-alcohol dry wines. The Mission is and will remain a significant grape in California for the production of sweet wines. Though one rarely or never sees the Mission grape identified on wine labels today, there were 1,800 acres of Mission vines in California in 1986, linking the modern industry to its origins.

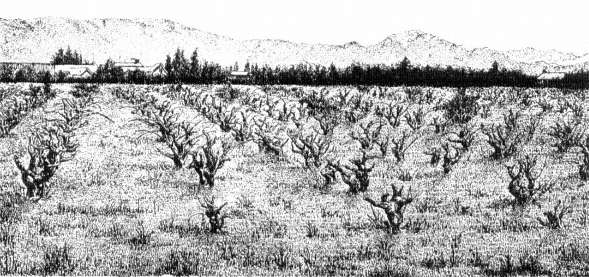

Colonial New Mexico (including much of present-day west Texas and all of Arizona) remained Spanish until Mexican independence in 1821; not until that time was there any communication or commerce between this remote northern outpost of Spain in the New World and the United States. After 1821 the opening of the Santa Fe Trail brought Americans into the valley of the Rio Grande—the Rio del Norte as it was then commonly called—and reports of its grapes and wines began to make their way back to the East. Small vineyards were scattered along the hundreds of miles of the river from Bernallilo southwards, but there was no trade in wine. The New Mexicans had no transport, few wooden vessels, and even fewer bottles, so that the wine they made was strictly for local consumption. The methods of New Mexican viticulture were described in 1844 by Josiah Gregg, the historian of the Santa Fe Trail. The grape vines grew unsupported, and by being pruned back heavily were made to grow as low bushes; this allowed the grower to dispense with any complicated apparatus of posts and wires and trellises, and it also made it possible to cover the vines with earth in winter to protect them against freezing. For, though New Mexico is hot in summer, it lies high and dry and is subject to some sharp winter weather. From these low shrubs the Mexicans obtained "heavy crops of improved and superiorily-flavored grapes," as Gregg rather confusedly put it—though clearly he found them good.[3]

After the annexation of the New Mexico territory in 1848, making it supply the nation with wine was at least conceivable. As the young U.S. attorney of the territory, William Davis, wrote in 1853: "No climate in the world is better adapted to the vine than the middle and southern portions of New Mexico, and if there was a convenient market to induce an extensive cultivation of the grape, wine would

67

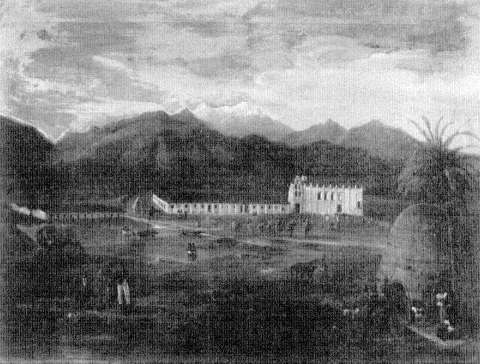

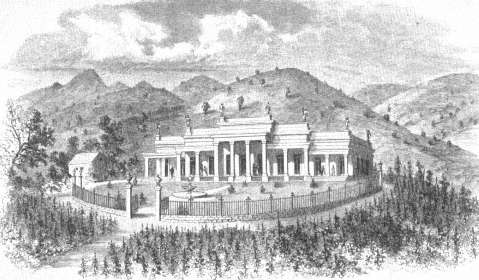

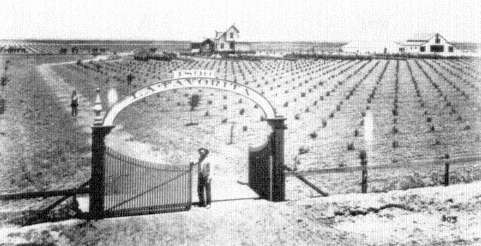

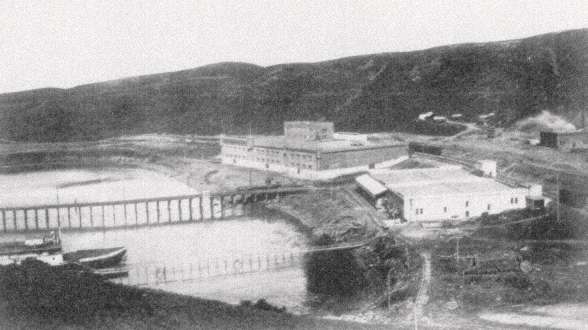

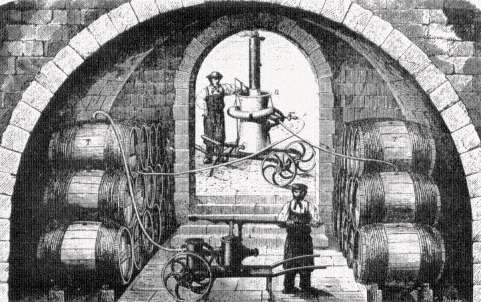

El Paso, Texas, whose "Pass wine" was known throughout the Southwest in the

ear of the Santa Fe Trail. This was the first region added to the United States in

which wine from vinifera grapes was produced. (From William H. Emory, Report

of the United States and Mexican Boundary Survey [1857])

soon become one of the staples of the country, which would be able to supply a large part of the demand in the United States."[4] The prospect was not necessarily illusory, but the history of New Mexico has not worked out that way. The production of wine in the state down to the most recent years cannot have been much greater than it was in colonial days. That is now changing, however, as New Mexico is currently the scene of large-scale investment—mostly of European money—in vineyards and wineries. It is far too early even to guess what the outcome of this sudden transformation of things will be, but it is particularly interesting as a renewal of winegrowing at one of its earliest sites in the United States.

Far to the south, at El Paso, where the Rio Grande comes out of the mountains to flow through a warm, low valley, winegrowing was extensive enough to support a trade and to acquire a reputation. The region—the American part of which is now in Texas—saw its first settlement in 1659, on the site of the present Mexican city of Juarez. Here orchards and vineyards flourished under irrigation; the vines, a Franciscan reported in 1744, "yield abundantly and produce fruit of good flavor and a rich wine in no way inferior to that of our Spain."[5] Early in the nineteenth century E1 Paso wine was the only revenue-producing crop in the whole province of Spanish New Mexico: "In no other country in America (so travelers declare) can wine be found with the taste and bouquet of the wine of New Mexico, especially

that produced in the large vineyards of E1 Paso del Norte. Its abundance is shown by its price, which is one real per pint, two hundred miles from the place where it is produced."[6] The reputation of El Paso wines was perpetuated by the Santa Fe traders, though one may doubt that they were very discriminating judges. "Pass Wine," they called it, and gave it preference over the wines produced closer to Santa Fe. E1 Paso brandy—aguardiente —was also famous, and perhaps even more in demand among the men of a trader's wagon train.

Most enthusiastic of all about E1 Paso wine was a young Missourian named John T. Hughes, a private in Colonel Alexander Doniphan's military expedition to New Mexico in 1846 who afterwards wrote a history of the affair. In that book, Hughes prints a copy of a letter that he was moved to send to the War Department after he had had a chance to look around him in the "fruitful valley of E1 Paso," where Doniphan's troops had arrived in December 1846:

The most important production of the valley is the Grape, from which are annually manufactured not less than two hundred thousand gallons of perhaps the richest and best wines in the world. This wine is worth two dollars per gallon, and constitutes the principal revenue of the city. Thus the wines of El Paso alone yield four hundred thousand dollars per annum. The El Paso wines are superior, in richness of flavor and pleasantness of taste, to anything of the kind I ever met with in the United States, and I doubt not that they are far superior to the best wines ever produced in the valley of the Rhine, or on the sunny hills of France.[7]

It was obvious to Hughes, and so he advised the War Department, that an energetic American population should displace the languid Mexicans; production of wine would then increase tenfold, and a link—road, railroad, or canal—between the valley and the United States would take the wine to a ready market. Hughes favored the plan of canalizing the Rio Grande from the Gulf to the falls at E1 Paso.[8] What answer the War Department made we do not know. No canal was dug, and the vineyards of E1 Paso seem to have declined through the rest of the nineteenth century under gringo auspices. When the Patent Office's viticultural explorer H. C. Williams arrived in the valley in 1858, he found that very few vineyards had been established on the American side of the river, and that the production of the whole region was declining.[9] There were then three qualities of wine produced by the El Paso vintners: a first-quality light red wine; a second-quality darker wine, the one properly called "Pass Wine"; and a third-quality wine left to the poor.[10] Here is how Williams described the methods of production he found in E1 Paso:

An ox hide is formed into a pouch, which is attached to two pieces of timber and laid on two poles supported by forks planted in the ground-floor of the room in which the vintage takes place. The grapes are gathered in a very careless manner, and placed in the pouch until it is filled. They are then mashed by trampling with the feet. In this condition the mashed fruit, stems, and some leaves remain until fermentation takes place, which requires from fifteen to twenty days. An incision is made in the lower part of the pouch, through which the wine drips; it is transferred to barrels. The wine now

has a flat, sourish taste. Should it be desired to make sweet wine, grape syrup, made by evaporating fresh juice, is added until the wine has the desired sweetness. It is not afterwards fined, or racked off, but remains in the cask until used.[11]

It was just this pastoral simplicity that so annoyed the Americans who observed winemaking in E1 Paso. Colonel William Emory, who conducted the official survey of the Mexican-American border, saw the neglected potential with exasperation. He had, he wrote in his official Report , drunk wine in El Paso "which compared favorably with the richest Burgundy." But there was no control and so no consistency—the next wine might well be "scarcely fit to drink." The promise was great, for, he wrote, "in no part of the world does this luscious fruit flourish with greater luxuriance than in these regions, when properly cultivated." The reason that nothing adequate to develop the promise had been done was, in the colonel's judgment, quite simple:

No one of sufficient intelligence and capital, to do justice to the magnificent fruit of the country, has yet undertaken its manufacture. As at present made, there is no system followed, no ingenuity in mechanical contrivance practised, and none of those facilities exist which are usual and necessary in the manufacture of wine on a large scale.[12]

Despite the optimistic views of writers like Hughes, Williams, and Emory, the Americans never took hold of the chance to develop the winegrowing of the Rio Grande Valley. There were reasons enough for this state of affairs: the isolated, underpopulated character of the region, the imperfect harmony between the Mexican-Indian cuisine and wine (compare the relative unimportance of wine in Mexico itself); and most of all, no doubt, the quick growth of California and its wine industry within a few years of the transfer of New Mexico to the United States. The situation is now undergoing a rapid and dramatic change, and the development of winegrowing in Texas and New Mexico will be one of the most interesting ventures in the history of American wine in this decade.

Winegrowing in the California Mission Period

Hundreds of miles to the west of the Rio Grande, along the Pacific coast, the widely scattered small mission communities and the great, isolated ranchos of Mexican California were beginning to be infiltrated by Yankee adventurers and traders at just about the same time as such people began to appear in New Mexico. Grapes and wine were among the first things to interest them there, as they had done in New Mexico, for there was in California, as in New Mexico, an already established tradition of winegrowing. Though of much younger date, it was, like that of New Mexico, developed in connection with the missions, was directed by the Franciscans, and was based on the Mission grape. Unlike that in New Mexico, it survived Americanizing and secularizing, flourished under alien hands, and grew rapidly

into a major economic force. Since the years just after the Civil War, the story of American wine has been dominated by California, and by an industry inherited directly from the Franciscan founders.

The first mission in Alta California—the region that became the American state—was founded by Fray Junípero Serra at San Diego in 1769, where, accompanied by soldiers and priests, he took the first step in the spiritual conquest of the Indians and towards the secular control of the coast, so long neglected by European powers, against all rivals. It is convenient to date viticulture in the state from this event; it was, indeed, so dated when the state celebrated the bicentennial of the wine industry in 1969. But that was a mistake. True, General Mariano Vallejo late in the nineteenth century affirmed that his father, who was among the first contingents of soldiers sent to Alta California, told him that Padre Serra brought the first vines and planted them at San Diego; another source (Arpad, son of the famous Count Agoston Haraszthy) says that this was done in 1769 or 1770.[13] These are both impressive witnesses. Yet such documentary evidence as exists for the earliest mission years plainly contradicts their testimony. As Father Serra moved back and forth along the coast, founding mission after mission in the chain that ultimately stretched north of San Francisco Bay to Sonoma, he regularly complained of the difficulty of obtaining a supply of wine for the celebration of the mass; such wine as he did get was clearly imported from Mexico or Spain, not the produce of local missions.[14] In the early part of the nineteenth century, for example, Mission San Gabriel was recognized as the largest producer of wines in California, yet as late as 1783, fourteen years after the first mission had been founded and twelve years after the founding of San Gabriel, Serra wrote that San Gabriel had no wine at all, the barrel sent to it on muleback from the coast having slipped and broken so that all the wine was lost.[15]

The first clear reference to the planting of grapes at a California mission comes from San Juan Capistrano in 1779, ten years after the arrival of the Franciscans in California.[16] These vines might have produced a small crop as early as 1781, but the evidence points to 1782 as the likeliest date for California's first vintage. In an original and important essay Boy Brady has not only established this chronology for the first California wine but has also plausibly identified the means whereby the vines were first brought to the state; they came, he suggests, in May 1778 on board the supply ship San Antonio under the command of Don José Camacho.[17] If so, the state has a neglected benefactor long overdue for public recognition.

The beginning made at San Juan Capistrano (and perhaps at San Diego in the same season) grew, in time, to include the entire system of missions, with uneven but substantial success. Santa Cruz, at the north end of Monterey Bay, was not successful in growing grapes. Neither was Mission Dolores in San Francisco, being too cool and foggy; yet the California pioneer William Heath Davis reported that in 1833 he had frequently drunk the wine of Mission Dolores, as fine a California red as he ever had, "manufactured at the mission from grapes brought from the missions of Santa Clara and San Jose."[18] Mission San Gabriel, a few miles east of

68

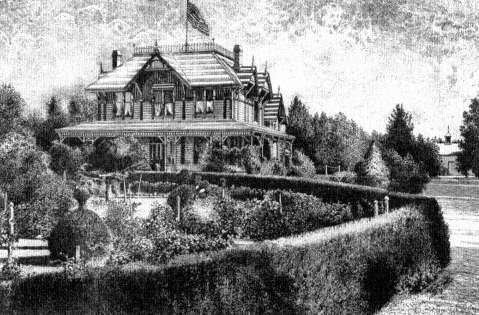

Mission San Gabriel, painted in 1832 at the height of its prosperity by the German

Ferdinand Deppe—the only known painting of a California mission from so early

a date. Its wine, for the celebration of the mass, for the occasional use of the fathers,

and for the entertainment of visitors, was highly regarded in Spanish California. From

the vines of San Gabriel developed the vineyards of Los Angeles, from which, in turn,

the winegrowing industry of California grew. (Santa Barbara Mission Library-Archive)

Los Angeles, eventually developed into the largest and most prosperous of all the mission establishments; it stood first in the size of its winemaking operations, too, and for some judges at least, in the quality of the wine it produced. The original vineyard at San Gabriel was called the Viña Madre—"Mother Vineyard"—a name that has created some confusion by its implication that this was the original of all the mission vineyards. It was not that, but was, instead, the first of the several vineyard properties that the mission developed in the large surrounding valley it presided over.[19] Father José Zalvidea, a tough, capable Biscayan, is credited with developing viticulture at San Gabriel, over which he ruled from 1806 to 1827.[20] By 1829 the American merchant Alfred Robinson wrote that the San Gabriel grapes annually yielded from four to six hundred barrels of wine and two hundred of brandy, from which the mission received an income of more than twelve thousand dollars.[21] Robinson's figures are unquestionably exaggerated, but they tell us clearly that observers were impressed by what they saw being done under Father Zalvidea and his successors.

Reliable statistics for the mission period do not exist. San Gabriel is said to have had 170 acres in vines and to have produced 35,000 gallons a year[22] —a modest figure if the acreage is accurately given: but then a good deal of wine was turned into brandy. Father Duran, a Franciscan who enjoyed a good reputation for the wines and brandy that he produced at his mission of San Jose, thought that the best wines of the whole mission system were those of San Gabriel.[23] But it was not without competition. General Vallejo is reported by Haraszthy as saying that the wine of Sonoma, last and most northern of the missions, "was considered by the Padres the best wine raised in California."[24] But then Vallejo had taken over those Sonoma vineyards and had an interest in promoting their reputation (so, too, did Haraszthy for that matter). The Sonoma Mission vineyard was tiny, so that not many can have known its wines, whatever their reputation may have been. Another judgment on mission wines was delivered by an observant Frenchman, Captain Auguste Duhaut-Cilly, who in 1827 decided that it was at San Luis Rey, between Los Angeles and San Diego, that there were "the best olives and the best wine in all California." He acted on his judgment by taking some of the mission's wine back with him to France: "I have some of it still," he wrote in 1834. "After seven years, it has the taste of Paxaret, and the color of porto depouillé."[25] This makes it clear that the wine was of the sweet fortified kind, on the model of angelica. Paxeret or Pajarete is an intensely sweet Spanish wine of the Pedro Ximénes grape grown in the town of Paxarete. Porto depouillé means literally a well-fined port, perhaps suggesting one that through age has begun to lose color. It is not clear to me whether Duhaut-Cilly's description indicates a red wine grown pale with age, or a white one grown brown—the latter, I suspect, for that would agree with the report described below of the mission wine drunk by a curious gourmet in the twentieth century.

After San Gabriel, the next largest of the mission vineyards was at San Fernando, also in the region of Los Angeles. San Fernando had only about a fifth of the winemaking capacity of San Gabriel, yet it was considerably larger than those next in line, the missions at Ventura and San Jose.[26] Many of the figures on the missions are more than ordinarily untrustworthy, being taken from inventories made after the secularization of the missions, when the vineyards, along with the other temporal interests of the Franciscans, had long been neglected or even abandoned. It is enough to say that at one time or another almost all of the missions made wine both for the table and for religious purposes, and that at a few the production of wine and brandy was a business of modest significance.

At San Gabriel, about which more seems to be known than any other of the missions, there were four sorts of wine produced, described in a letter from Father Duran to Governor José Figueroa in 1833. Two were red—one dry, "very good for the table," the other sweet. Two were white, one unfortified and the other strengthened with a quantity of grape brandy.[27] In all probability, though the description is not as clear as one would like, the fortified white wine of San Gabriel is the original of the wine called angelica, once the most famous produce of the Los

Angeles county vineyards. Angelica, as it used to be made (and apparently is no longer), was not so much a wine as a fortified grape juice, such as the French call mistelle and the Spanish mistela: this is a drink that properly belongs to the class of cordials rather than of wine (compare the Scuppernong wines of North Carolina). To a must that has not yet begun to ferment, or has only partially fermented, brandy is added in such quantity as to arrest the action of the yeast. This was an effective way to handle the Mission grape, which under the hot skies of southern California gave a fruit almost raisined, rich in sugar but low in acid, so that its dry wines were flat and unpalatable. With the sweetness retained, and the preserving alcohol supplied by the addition of brandy, the juice, christened angelica after the City of the Angels, became a popular wine—some will say deservedly, others not.

The methods used in the missions were of the simplest, though such descriptions as exist do not always agree and are not always very clear. As in New Mexico, the ready availability of cowhides and the relative scarcity of wood determined the choice of materials. The standard method of crushing seems to have been by pouring grapes onto a cowhide, perhaps suspended over a receptacle, and then setting an Indian to treading the grapes with his feet. The juice expressed by this means was caught in leathern bags, in barrels, or in brickwork cisterns (some of these remain at San Gabriel), where it fermented; red wine, of course, fermented on the skins and stems of the crushed grapes; for white wine, the juice was drawn off to ferment separately. The skins might then go into a primitive still for brandy.[28] Most of the Franciscan fathers were natives of Spain and may be supposed to have had at least a general notion of how wine was made. We know that at one mission there was a copy of a winemaking guide, the second part of Alonso de Herrara's Agricultura general , in an edition published at Madrid in 1777.[29] The work was originally published in 1513, a fact that sufficiently indicates the conservative instincts of the Spanish, whether in the Old World or the New.

Whether the missions had wine in sufficient quantity to make it an item of commerce, how extensive that commerce was, with whom it was carried on, and how long it lasted, are all questions without distinct answers.[30] Until the overthrow of Spanish rule, all foreign commerce was forbidden, so at best the trade in mission wine was restricted to the brief span from the beginning of Mexican rule in 1821 to the secularization of the mission properties in 1833. The reports of travellers from the 1820s and afterwards make it sufficiently clear that mission wine then was at least available for the priestly table as well as for the altar—"plenty of good wine during supper" is the remark of one of Jedediah Smith's party at San Gabriel in 1826;[31] and we have seen how in the next year Duhaut-Cilly was able to take wine from San Luis Rey to France, and how, in 1829, Robinson could speculate on the large income brought to Mission San Gabriel by its wines. There is nothing coherent or distinct in all this, however. Father Payeras, president of the missions, made a contract in 1823 with an English firm trading to Lima to supply mission produce for a term of three years.[32] Among the goods listed as items of trade, wine and brandy are named; but no price is attached to them, and it is not likely that

69

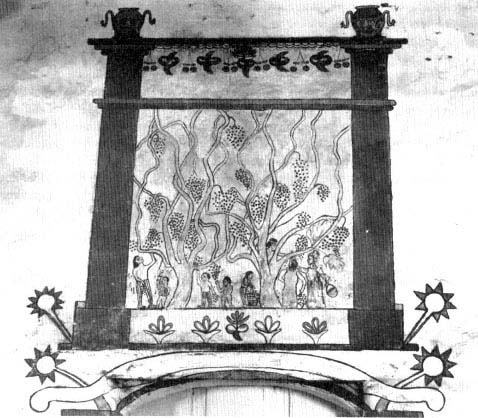

Wall painting in the sala of the fathers' dwelling, c. 1825, Mission San Fernando, California,

showing the Indian "neophytes" harvesting grapes—a unique combination of native American

art and the Mediterranean tradition of winegrowing. The painting was destroyed in the earthquake

of 1971. (Courtesy Dr. Norman Neuerberg)

much can have been shipped to Peru. At best one may cautiously suppose that during the 1820s a few of the missions could afford to manage an intermittent trade in wine, largely with and through the ships that coasted the shores of California.

Whatever trade the missions may have had in their hands came to an end beginning with the decrees of secularization passed by the Mexican government in 1833. By this act the Franciscans were stripped of their temporalities and restricted to the spiritual care of the missions, presidios , and pueblos of Alta California. The decree did not take effect at once or uniformly: the work of expropriation proceeded unevenly; some missions held out longer than others; and California was in any case far distant from the central authority in Mexico. Thus we find that years after the decree some missions were still cultivating their vineyards.[33] But the back of the enterprise had been broken. At San Gabriel, to take that place again as an

image of the whole, the father superintendent ordered the large vineyards of the mission to be destroyed in the face of the decree of secularization. His order, so the tradition goes, was refused by the Indians, who, one supposes, were not about to destroy the source from which their aguardiente flowed.[34] Nevertheless, the good days were over. By 1844, so a modern historian of the Franciscans in California writes, "the mission had nothing left but some badly deteriorated vineyards cared for by about thirty neophytes" (Indians attached to the missions).[35] And at San Diego, a couple of years earlier, a French traveller had sadly observed vineyards stretching around the ruined mission that were "capable of furnishing the best wine in California" but that now lay uncared for and idle.[36]

Mission wine, which thus became practically extinct in the second quarter of the century, nevertheless had a curious survival in an unlooked-for part of the world. In the 1920s, in Paris, an English wine lover encountered an expatriate Pole who told him that, at the turn of the century, at Fukier's, the best restaurant in Warsaw, "the choicest and most expensive dessert wine" came from California. The Englishman, finding himself not long after in Warsaw, remembered what he had been told, went to the famous restaurant Fukier and asked for its California wine. He naturally supposed that it must be California wine such as other restaurants had, and was curious to know how it could be both the most expensive and the best available in a distinguished restaurant. The waiter told him that, fortunately, there were a few bottles still left, some of which were brought to the curious diner: "Imagine my surprise when I found that they were of wine from the Franciscan missions of California grown during the Spanish period, a century and a half or so ago. The wine was light brown in colour, rather syrupy, resembling a good sweet Malaga in taste, and in good condition."[37] The age is a bit exaggerated—in all likelihood the wine was from the 1820s and therefore just a hundred years old—but the recrudescence of such a wine in so unexpected a place is sufficiently surprising and pleasing. The description is pretty much what one would expect if the wine were an angelica type such as described earlier. And it is curious to note that this latter-day description agrees with one of the earliest accounts of mission wine: the German traveller Langsdorff, calling at Mission San Jose in 1806, noted that the wine of the place is "sweet, and resembles Malaga."[38] It is not likely now that anyone will ever have a chance again to taste the Franciscan wine of Old California.

The Beginning of Commercial Winegrowing in Southern California

Even before the expropriation of the mission lands, a small, very small, beginning of a secular viticulture, parallel to that of the missions, had been made. There is indirect evidence of vineyard planting in the pueblo of Los Angeles in the first decade of the nineteenth century or even earlier.[39] After Spanish rule, with its jealous exclusion of all foreigners, had been replaced by the loose, inefficient, and

more hospitable Mexican rule, outlanders began to arrive in small numbers in California, some of them planting vines and making wine along with their Mexican neighbors. Los Angeles, in the brief interval between California's Spanish and American phases, became a quite cosmopolitan village, including miscellaneous Yankees and a sprinkling of Irishmen, Englishmen, Frenchmen, Italians, and Germans, not to mention Hawaiians, who were the most sought-after crewmen for ships in the Pacific trade.

In writing about early California—that is, California at any time before the Gold Rush—one must be careful to emphasize how tiny the extent of settlement throughout the state was. At the beginning of the century there were, through all the hundreds of miles of the state's length, only the missions, plus four presidios (army posts) at San Diego, Santa Barbara, Monterey, and San Francisco, and three pueblos (civilian communities)—Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, and San Jose. A few families would also have lived on the great ranchos belonging to the missions. The total number of inhabitants, exclusive of the Indians (fast dying out under the fatal impact of the West), could be counted in the hundreds.[40] After the end of Spanish rule, this number of course grew, but not by much. If we keep this circumstance in mind, it is clear that to talk about the development of a wine industry before the 1950s is a bit comic, the term industry having an absurd grandiloquence when measured against the actual scale of things. Nevertheless, there were interesting beginnings, some quite distinct phases of development, and a good many names that deserve to be perpetuated.

Since the situation is very different now, it is worth stressing the fact that commercial winegrowing in California after the mission era began around Los Angeles, and that southern California continued to dominate the scene for the next fifty years. The dusty pueblo of Los Angeles, founded in 1781 on the bank of the Los Angeles River, lived, like the missions, mainly on the trade in hides and tallow. The town stood at the foot of bluffs, but on three other sides the land was a flat plain, easy to irrigate, so that fruit trees, olives, and vines did well. To travellers coming up over the flatlands leading from the landing place at San Pedro on the south, or from the east through the mountain passes, Los Angeles was a green oasis, its low-roofed adobes embowered in willows, vines, and fruit trees. The vines were from the missions, and those who grew them had probably learned what they knew of viticulture from the missions too, so that California winegrowing is continuous with the mission tradition; there was no hiatus between the end of the one and the beginning of the other, for they had overlapped for a long time before the missions came to an end.

When the men of Gaspar Portola's expedition came, in 1769, to the site along the river where, later, Los Angeles was to be settled, they found growing there "a large vineyard of wild grapes and an infinity of rosebushes in full bloom,"[41] so the indications for grape growing were excellent from the start. We do not know who it was who planted the first vineyard in or around Los Angeles not belonging to a mission. He would certainly have had a Spanish name, though, and he must have

planted before the end of the eighteenth century. A possible candidate is José Maria Verdugo, who planted a vineyard before 1799 on the Rancho San Rafael north of the pueblo .[42] Antonio Lugo, who planted a vineyard not long after 1809, is the earliest vineyardist in Los Angeles itself whose name we know.[43] By 1818 the town was reported to have 53,000 vines, and ten years later an official report noted that a succession of good vintages had given encouragement to winegrowing there.[44]

The name of the first American grower in Los Angeles, and therefore in California, is on record. He was Joseph Chapman, from Massachusetts, who came to California on a buccaneering expedition to Monterey in 1818, was captured and jailed by the Spanish, and, on his release, drifted to the southern part of the state. At San Gabriel he became a general handyman, functioning as carpenter, blacksmith, and apothecary at the mission.[45] In return, Chapman—called José Huero, "Blond Joe," by the Californios[46] —learned at the mission whatever he knew of grape growing and winemaking. By 1822 Chapman had moved to Los Angeles; in 1826 he bought a house there and set out 4,000 vines.[47] Here, for the next decade or so, Chapman grew grapes and, presumably, made wine, for there was no other economical use for his harvest. After the secularization of the missions, Chapman moved on to Santa Barbara, and then to property in Ventura County; he died at Santa Barbara in 1849. A vineyard in Los Angeles remained in the hands of Chapman's son Charles as late as 1860, however, so that this first American vineyard had a reasonable longevity.[48]

As California began to draw Americans both by sea and overland, others took up vine growing: Richard Laughlin, who had arrived overland as early as 1828 in Los Angeles, at some time unrecorded set out a vineyard; so did William Logan in 1831 and, later in the decade, William Chard and Lemuel Carpenter.[49] But in polyglot Los Angeles the Americans were merely one element among several in the general activity of vine growing. Besides, most Americans moved on to other parts of the province after only brief stays, and most tried their hands at all sorts of enterprises, among which viticulture had no very important place. At least one grower in Los Angeles was a Dutchman, going under the name of Juan Domingo (John Sunday). His real name was Johann Groningen; he was a sailor, whose ship had been wrecked in San Pedro Bay on Christmas Day, 1828, a Sunday. When he reached the shore in safety, he sensibly resolved to abandon the sea and to settle where he found himself. The locals gave him his name as a symbol of his experience. So the story goes; but since Christmas fell on a Thursday in 1828 it must need adjusting in some details.[50] Juan Domingo worked as a carpenter, planted a vineyard, married, raised a family, and spent the rest of his days in Los Angeles. Several growers were French: Louis Bouchet (or Bouchette or Bauchet—the spelling varies), a cooper by trade and a veteran of the Napoleonic wars, came to California in 1828 and must have been among the earliest of the newcomers to plant a vineyard. On his death in 1852 the inventory of his property included two vineyards and such winery equipment as a still, some casks, and earthen jars.[51] Victor Prudhomme and Jean Louis Vignes were other Frenchmen established among the

vine growers of Los Angeles in the 1830s.[52] Most were of course Mexican: Manuel Requena, Tiburcio Tapia, Ricardo Vejar, and Tomas Yorba are among the names of notable early vineyardists in the Los Angeles region.[53]

Theirs was strictly a cottage—or backyard—industry. One estimate gives Los Angeles 100,000 vines so early as 1831, but this is almost certainly too high.[54] By an exceedingly moderate computation, such a quantity of vines would have yielded 30,000 gallons of wine a year, and it is hard to see how the local market of a few hundred men, women, and children could have blotted up all that liquid, even supposing that much of the vintage was converted into brandy, as it must have been. There is no reason to think that the wine and brandy produced in early Los Angeles was destined for any but a purely local trade, including the ships that put in at San Pedro at not very frequent intervals. The wine, coming as it did from the Mission grape, and handled under conditions of primitive simplicity, could not have been good. One judgment, expressed in 1827, was probably fair enough: the grapes of Los Angeles, Captain Duhaut-Cilly wrote, were quite good, but the wine and brandy made from them were "very inferior . . . and I think this inferiority is to be attributed to the making rather than to the growth."[55] Yet even had the making been better, the result would still have been limited by the inherent defects of the Mission grape.

Winemaking in Los Angeles was raised from a domestic craft to a commercial enterprise by a Frenchman with a name too good to be true, Jean Louis Vignes—because of his name, a French compatriot has written of him, "he seemed predestined to become the Noah of California."[56] Given his destiny, Vignes was not only well named but well born, for his native place was Cadillac, a winemaking community in the Premieres Côtes de Bordeaux, where his father was a cooper. Jean Louis learned the cooper's trade, married, and lived quietly until 1826, when, at the age of forty-seven, and for reasons still quite obscure, he left home, wife, family, and trade to go to Hawaii. He could not get satisfactory work in the islands, however, and he had to live from hand to mouth for a time. At last, in 1831, he left for Monterey. The precise date of his arrival in Los Angeles is not known, but he was established in that town by 1833, perhaps drawn there by the reputation of its vineyards and the presence of a Frenchman or two.

He was somehow able to buy a hundred acres of land.[57] The property lay on the east side of the pueblo , along the river, and was marked by a great sycamore tree of venerable age called E1 Aliso, to give it the capital letters that all observers agreed that it deserved. Vignes himself came to be called Don Luis del Aliso in honor of his splendid tree. Here Vignes laid out a vineyard that ultimately occupied thirty-five acres and began the manufacture of wine and brandy.

It did not take him long to recognize the inadequacy of the Mission grape, for in 1833 Vignes imported European varieties from France, sent to him by way of Boston and then around the Horn.[58] Vignes thus lays claim to be the first to take the crucial step of obtaining better varieties. We do not know what varieties he imported, however, nor what success he may have had with them, nor whether they

70

Edward Ord's map of Los Angeles, 1849, from the copy in the Huntington Library. This is

the earliest map of the town after the American annexation. The fields between the town

and the river shown closely dotted are planted in vines. Just above and to the right of the

island in the river are the vineyards of Jean Louis Vignes.

entered importantly into the wine he made. The high reputation that his wines established in competition with others from Los Angeles suggests that perhaps they did, but it is also clear that the Mission continued as the overwhelmingly dominant variety in Los Angeles vineyards. If Vignes did actually show a better way, no one yet troubled to follow him. For many years in California it was the custom to call all grapes other than the Mission "foreign." The Mission is an unquestioned vinifera, and so just as "foreign" as any other European grape: but the distinction made by the locals is an interesting reflection of their experience.

By making acceptable wine in considerable quantity, Vignes was able to take

another step forward in 1840, when, through the agency of his nephew Pierre Sainsevain, newly arrived from France, he made the first recorded shipment of Los Angeles wines. Sainsevain loaded a ship at San Pedro with white wine and brandy and took it to Santa Barbara, Monterey, and San Francisco; at each of these places he was able to get good prices for his cargo.[59] This venture does not seem to have been regularly followed up, but it at least showed the way to an important -later trade.

One of Vignes's most enthusiastic admirers was the pioneer California merchant William Heath Davis, whose classic Seventy-Five Years in California is the source of much detail about Vignes and his E1 Aliso vineyard. Davis regarded Vignes as "one of the most valuable men who ever came to California [he and Davis had arrived on the same ship in 1831], and the father of the wine industry here." Davis, who dealt in wines among other commodities, gave a present of "fine California wine" from Vignes's cellar to the American Commodore Thomas Ap Catesby Jones when the latter was at Monterey after his premature capture of the city.[60] Later (1843), when Jones was in Los Angeles, he and his officers called on Vignes at E1 Aliso: they inspected his cellars, sampled his wines, and accepted a gift of several barrels of "choice wine." Vignes asked them to save some of their gift wine to present to the president of the United States, "that he might know what excellent wine was produced in California."[61] On an earlier visit to Vignes in 1842, Davis, too, had been impressed by the cellars and the old vintages they contained. Vignes himself was full of prophetic enthusiasm about California as a wineland. It would, he said, rival "la belle France," and he had urged a number of his relatives and of "his more intelligent countrymen" to come to California and enter the business of winegrowing.[62]

How many Frenchmen Vignes may have enticed to California is not known (estimates vary widely as to the French population of those days), but when Captain Duflot de Mofras called at Los Angeles in 1842, Vignes, "on behalf of the French colony," presented the captain with a barrel of California wine to be offered to Louis Philippe. Unluckily, as we learn, the wine, having survived the hazards of shipment from California, was destroyed by fire in Hamburg before it could be presented to the king for his royal judgment.[63]

Vignes, who was born in 1779, continued to cultivate his vineyard and make wine until 1855, when he sold his property to his Sainsevain nephews for $42,000, one of the greatest commercial transactions that Los Angeles had ever seen.[64] Seven years later, Vignes died. The huge sycamore, E1 Aliso, that stood at the gate of his property, lasted some years longer, but was cut down before the end of the century; the remarkable grape arbor that ran from Vignes's house down to the river, perhaps ten feet wide and a quarter of a mile long, has long since been displaced by industrial building. It was, while it stood, one of the public places of Los Angeles, where receptions could be held and parties given under the grateful shade. Vignes himself is still remembered for his effective pioneering, a fact that would have pleased his friend Davis, who wrote in affectionate memory of Vignes

that "it is to be hoped that historians will do justice to his character, his labors and foresight."[65]

Almost as prominent as Vignes in the same generation was a winegrower of very different origin and background. William Wolfskill was a frontiersman, born in Kentucky but growing up in Missouri at a time when the territory was still Indian country.[66] In 1822 he accompanied the first American trading expedition to Santa Fe, and for some years afterwards he lived and traded in New Mexico. At one point he travelled to E1 Paso to buy "Pass Wines" and "Pass Brandy" for trade, and so established the only link I know of between the winemaking history of Mexican New Mexico and Mexican California. In 1830 Wolfskill led an expedition for the purposes of fur trapping from New Mexico to California, along what later became known as the Old Spanish Trail, through Colorado, Utah, and Nevada, and into California across the Mojave to the Los Angeles basin, where the party arrived in 1831. Fur trapping was no longer particularly rewarding—around Los Angeles the prey was the sea otter—and after an unremunerative effort in the first ship known to have been built in Los Angeles, Wolfskill decided to try another line. He bought land already planted with vines by an anonymous Mexican and settled down in Los Angeles in 1833. Three years later he added more land, and then, in 1838, traded for a hundred-acre tract on the southeast outskirts of the town, where he developed a substantial vineyard and produced wine steadily until his death in 1866[67]

By that time his vineyards and orchards covered 145 acres; the vineyards had been recognized as "best in the state" at the California State Fair in 1856 and again in 1859, and his wine production was up to 50,000 gallons.[68] Besides that, much of his produce went to market as fresh grapes, some he sold to other winemakers, and another part went into brandy. Wolfskill and Vignes were neighbors—everyone was in the Los Angeles of those days—and presumably friendly rivals for the lead in Los Angeles winemaking. Wolfskill had his partisans. Edwin Bryant, whose visit to California in 1846 resulted in one of the first in the long string of books boosting the Golden State, paid a call on Wolfskill at his rancho, by then one of the small town's showplaces. Wolfskill, Bryant wrote, "set out for our refreshment three or four specimens of his wines, some of which would compare favorably with the best French and Madeira wines."[69] And as Vignes had sent wine to President John Tyler, so Wolfskill sent wine, including the sweet red wine called "Port" for which Los Angeles was then gaining a reputation, to President James Buchanan in 1857.[70] There is no evidence that Wolfskill made any effort to introduce new and better varieties into California, as Vignes is said to have done.

When, as an episode in the Mexican War, American forces occupied California, the wines of Los Angeles found a new clientele. The Americans entered the town in January 1847, having among them the Lieutenant (later Colonel) Emory whose remarks on New Mexico viticulture we have already met with. "We drank today," Emory wrote on 14 January, "the wine of the country, manufactured by Don Luis Vignes, a Frenchman. It was truly delicious, resembling more the best description of Hock than any other wine."[71] Another American who took an interest in the

local product was John Griffin, a surgeon with General Stephen Watts Kearny's army, who kept a diary. The entry for I 2 January 1847 tells us that a large quantity of wine and brandy had been seized and secured in order to keep it out of the hands of the sailors of Commodore Robert Stockton's squadron; Griffin added that the wine was "of fine flavour, as good I think as I ever tasted."[72] Griffin gave practical meaning to his praise of Los Angeles wines by returning to the city in 1854 and spending the rest of his days there. He is remembered as often talking of a marvelous wine that he had had in his army days—surely it was the wine of Jean Louis Vignes? Perhaps from a barrel looted by the soldiers, and without any identity beyond that?[73]

Vignes and Wolfskill, by virtue of their early start and the large production to which they eventually attained, stand out among the first generation of commercial winegrowers in Los Angeles. A good many other men joined them in no very long time, however, and by the 1850s it is possible to speak without exaggeration of a real industry in and around the city. William Workman, an Englishman, and his associate John Rowland, planted vineyards at their La Puente Ranch in the 1840s.[74] Hugo Reid, a Scotsman, put in a vineyard in 1839 at his Rancho Santa Anita, northeast of the town, and made wine there until he sold the property in 1846;[75] Matthew Keller, an Irishman who had once studied for the priesthood, arriving in Los Angeles in, 1851, soon developed vineyards third only to those belonging to Vignes and Wolfskill. Keller also deserves mention as one of the pioneers in importing new varieties to supplant the unsatisfactory Mission, and as the author of a report describing Los Angeles winegrowing in 1858, published in the U.S. Patent Office's annual report; this was the earliest authoritative description published for a national audience.[76]

Keller's enterprise outlasted those of Vignes and Wolfskill, and to the vineyard he established at the corner of Alameda and Aliso Streets in Los Angeles were later added hundreds of acres more at the Rising Sun Vineyard south of the city and at the Malaga Ranch, above Santa Monica. By 1875 Keller was described as a "wine making millionaire," and in that year one of the most splendid social occasions in Los Angeles was Keller's "First Annual Vintage Feast and Ball," at which the guests were offered "Claret, Eldorado, Madeira, Angelica, White Wine, Sherry, Port."[77] The financial crises of the 1870s brought Keller into trouble soon after. So did the much-complained-about practice of eastern dealers of adulterating and misrepresenting California wines. Keller went to New York in 1877 in order to act as his own agent, a move necessitated, as he sadly wrote, "to save my property and to get out of the wine business—and to do this I have risked my life in my old age in N.Y. in the depth of winter to try and accomplish it . . .. The wine business has been a millstone around my neck . . . It has swallowed up all I made on land sales and any other way."[78]

The troubles that Keller faced were shared generally: financial depression and overproduction in California combined to hurt most winegrowers. But the quality of at least some of his wines may have helped to injure Keller's business. In answer

to Keller's question about how a certain sherry had been made, for example, his winemaker and manager, Thomas Mahony, sent this astounding reply:

All I know about it now is that it was made of white wine, Spirits, Grape Syrup, Hickory nut infusion, Quassia, Walnut infusion and Bitter aloes, the proportions I could not tell to save my life. At the time I made it I noted down on cards the contents of each vat, so that I could continue to make it if it turned out well, but when I received your letter saying it was no account I tore up the cards.[79]

How, one wonders, would the eastern dealers manage to adulterate this compound? It was, perhaps, something more than business rivalry that led another Los Angeles winemaker to say of Keller in 1877 that "he has done more damage to the California wine trade than any other man in it."[80] Yet Keller is said to have been in correspondence with the great Pasteur on the problems of winemaking, and to have received an inscribed copy of Pasteur's Études sur le vin .[81] Keller was at last freed of his difficulties by his death in 1881, when the wines and vines of the Los Angeles and Rising Sun Vineyards with which he had made his name passed to the Los Angeles Vintage Company.

Other names among many that might be mentioned testify to the continuing international character of early Los Angeles: there were the Frenchman Michael Clement, the Swiss Jean Bernard, the Englishman Henry Dalton, and the Swiss father and son Leonce and Victor Hoover (originally Huber), all active among the viticulturists and winemakers of the pueblo . In a town with a population still fewer than 2,000, the grape growing and winemaking activity of Los Angeles must have been visible and dominating to a degree that few, if any, American towns have since known. When Harris Newmark arrived in Los Angeles from his native Germany in 1853, he found more than one hundred vineyards in the area, seventy-five or eighty within the precincts of the town itself; and, best evidence of all of the degree to which wine had established itself, he found that the Angelenos generally patronized the local product, which was so cheap that it sold for fifteen cents a gallon and was usually served free with meals.[82] Leonce Hoover patronized the local product to a remarkable degree: a committee of the State Agricultural Society, visiting Los Angeles in 1858, reported that he drank nothing but wine the whole day through, excepting one cup of coffee on rising: "At his meals, when at work, around the social board, on retiring at night—at any and all times, he drinks his pure juice of the grape with perfect freedom, and, as he assures us, without the least intoxicating effect."[83]

One should mention, too, the vineyards that had been established beyond the environs of Los Angeles, at Cucamonga and at Rancho Jurupa (now Riverside), many miles to the east. The Cucamonga Rancho, about forty miles from Los Angeles, had been granted to Tiburcio Tapia in 1839; he planted vines there in the spot now known as Red Hill.[84] Since Tapia's death in 1845 the property has passed through many hands and many vicissitudes, but a winery still stands there. It is no longer a producing facility, but serves as a retail outlet for another local wine

producer under the banner of "California's oldest winery." It may be. Cucamonga wines enjoyed a special reputation, apparently based on the high alcohol content generated in them by the hot sun in this interior valley. As one journalist wrote in 1861, "the wine made here is the most celebrated in the country, on account of its peculiar, rich flavor, being some twenty per cent above Los Angeles wine in saccharine matter."[85]

A few miles east and south of the Cucamonga vineyards is the Rancho Jurupa, where the city of Riverside now stands; the original grantee, Don Juan Bandini, built a home there in 1839, and probably began planting vines at the same time. He soon sold a part of his grant, and by the 1850s the new proprietor, Louis Robidoux, had 5,500 vines growing.[86] Both Cucamonga and Riverside continued to be wine regions after these beginnings, though urbanization has now, after nearly a hundred and fifty years, almost put an end to the vineyards that were planted in those early days. Other vineyards were scattered in various places at the eastern end of the Los Angeles basin—Dr. Benjamin Barton's ranch near San Bernardino, for ex-ample—but they did not compete in importance with the plantings around Riverside, and, especially, Cucamonga.

The main vineyard district of the city of Los Angeles itself was quite distinct and compact: it ran along both sides of the river, mostly on the west or city side, from Macy Street on the north to Washington Street on the south, and from Los Angeles Street to Boyle Heights going west to east. This section, in the heart of old Los Angeles, has long since been covered over by railway tracks, warehouses, the buildings of Little Tokyo, and freeways; even the banks of the Los Angeles River are now sheathed in concrete. But it is remarkable how the names that belong to its viticultural past persist. To the instructed eye the contemporary street map of Los Angeles reveals a generally unrecognized memorial to the early growers and wine-makers who lived there long ago. Aliso Street remembers Don Luis Vignes's great sycamore; the street itself, which was once the main route across the river, is now a mere remnant of its old self, functioning as a sort of high-speed alley giving access to the San Bernardino Freeway. In the same region, Keller Street, after Don Matteo Keller, and Bauchet Street, after Don Luis Bauchet, commemorate two of the vineyardists who once made the region green. A little to the south, Kohler Street preserves the name of the enterprising German who first brought Los Angeles wines into large-scale commerce. Just across the river, to the east, Boyle Heights reminds us of the Irishman Andrew Boyle, whose house on the heights looked down to his vineyards and cellars on the bottom lands along the river below.

A visitor to this section of the city today must use all the power of his imagination to reconstruct the vineyards that once fringed the river, making the dusty town appear a green haven to the weary traveller. The Hoover vineyards, the Keller vineyard, the Domingo vineyard, the Vignes vineyard, all on Aliso; the Wolfskill and Wilson vineyards on Alameda; and those of Antonio Lugo, John Moran, Julius Weyse, and John Philbin on San Pedro, to name no more, now seem as remote as the hanging gardens of Babylon. Only the names on the street signs attest that

here once grew the vines that made Los Angeles the fount and origin of wine in California.

Yet they did once grow there, and from them Los Angeles made its red and white wines, especially the whites for which it was most celebrated, including the sweet angelica. Brandy, too, was distilled, as it had been from the mission days. And fresh grapes formed a large and lucrative part of the traffic between Los Angeles and San Francisco, at least in the first few years after the rush of gold miners to the northern part of the state. Another continuity between commercial viticulture in Los Angeles and the mission days was the reliance upon Indian labor: as Matthew Keller wrote in 1858, "most of our vineyard labor is done by Indians, some of whom are the best pruners we have—an art they learned from the Mission Fathers."[87] Indians also did the hard labor of treading the grapes in those places where the simplicities of the mission style were still preserved. Harris Newmark, who arrived in Los Angeles in 1853, remembered how he was both fascinated and repelled by the sight of Indians in the vintage season, "stripped to the skin, and wearing only loin-cloths," trampling out the juice in large, elevated vats:

These Indians were employed in the early fall, the season of the year when wine is made and when the thermometer as a rule, in Southern California, reaches its highest point; and this temperature coupled with incessant toil caused the perspiration to drip from their swarthy bodies into the wine product, the sight of which in no wise increased my appetite for California wine.[88]

The Indians' reward was to be paid on Saturday evening. Then, as Newmark writes, they drank through Saturday night and all of Sunday; three or four were murdered each weekend, the invariable consequence of the general debauch, but such of them as survived were ready for work again on Monday: thus, at any rate, runs the account of an early settler.[89]

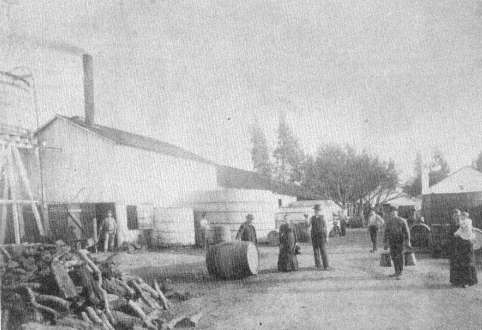

The wine trade of Los Angeles moved into its next phase in the middle of the 1850s, when two commercial wine houses, like those developed in Cincinnati at about the same time, were set up to consolidate the production, storage, and distribution of the region's wines. Second in order of founding, but older by virtue of continuing an already operating winery, was the firm of Sainsevain Brothers, Jean Louis and Pierre, the nephews of Jean Louis Vignes. When they bought out their uncle in 1855, they immediately proceeded to expand the scale of operations at the old El Aliso vineyard. They bought wine from other growers, as well as making it from their own grapes and those purchased from local vineyards. In 1857 they opened a store in San Francisco; by 1858 they led the state with a production of 125,000 gallons of wine and brandy.[90]

The fata morgana of the Sainsevain brothers was the wish to make champagne. Pierre, the younger, returned to France in 1856 to study the manufacture, and brought a French champagne maker back with him. In the season of 1857-58 sparkling wine was produced at the San Francisco cellars of the Sainsevain brothers.[91] They called it Sparkling California Champagne, and it was greeted with

much interest, shipments being made to New York and Philadelphia to give it the widest publicity. It was not, however, a success. The Mission grape was a poor basis for sparkling wine, which calls for a far more acid juice than the Mission can provide; besides, the Sainsevain methods were not good enough to prevent large losses from breaking bottles and from other causes. The brothers were soon in financial difficulties as a result of their investment in sparkling wine—they are reputed to have lost $50,000 in the venture.[92] Their partnership was dissolved some time early in the 1860s, and only Jean remained at the El Aliso property in 1865 when it was sold. Both Sainsevains, at different times and at different places, kept their hands in the California wine trade thereafter, but the firm was no longer a factor in Los Angeles.

More stable and successful was the enterprise of Kohler & Frohling, as it was also the earliest of the Los Angeles wine houses. It might in fact be said that the real commerce in California wines begins with the advent of Kohler & Frohling. Charles Kohler was a German violinist who emigrated to New York in 1850 and then went on to San Francisco in 1853, where he helped to found the Germania Concert Society and provided San Francisco with its introduction to classical music. Among the musicians in his orchestra was a flutist named John Frohling. Late in 1853, Kohler, Frohling, and a third musician, an operatic tenor named Beutler, inspired by some delicious Los Angeles grapes at a picnic lunch, resolved to go into the wine business. None of them knew anything about it; indeed, Kohler and Frohling had never even seen a vineyard. Beutler, however, was from Baden, and his enthusiasm for the vine apparently fired the others, who were certainly shrewd enough to see an opportunity and resolute enough to pursue it.[93]

They raised a capital of $12,000, and made their first step by purchasing a small vineyard of Mission vines in Los Angeles in May 1854; that autumn they crushed their first vintage with the help of some Rhinelanders they had been able to hire. Beutler, for personal reasons, soon dropped out of the partnership,[94] leaving its management to Kohler, the salesman, who remained in San Francisco to oversee the firm's marketing activity. Frohling was the production manager, operating out of Los Angeles, where the vineyards were. Whether this assignment of responsibilities was made for any special reason we do not know, but both men did their jobs well. They rented a cellar in the Montgomery Block of San Francisco to store the few hundred gallons of wine that they had made, and began to acquire a clientele among the French and Germans of the city. The example was not lost on the Americans, who also began to buy the wines of Kohler & Frohling; the business thereupon grew quickly. Not so quickly, though, that the partners could afford to give up their musical careers entirely. Until 1858 Kohler continued to depend upon his fiddle, and Frohling upon his flute, to make up by night the money that the firm may have lost by day. They were, evidently, musicians of ability, for they did not lack for work when they needed it.[95]

In that same year, 1858, Kohler & Frohling took the prize at the state fair for "best wine"; they had already garnered a "diploma" for their Los Angeles port in

71

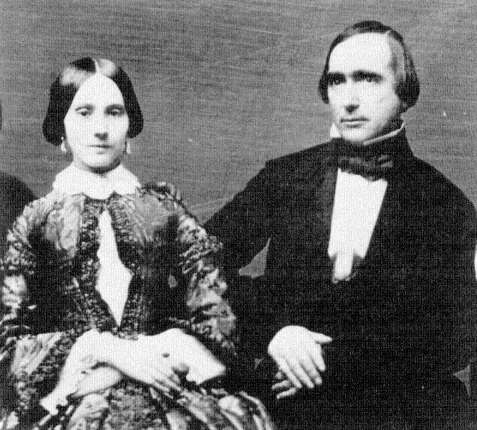

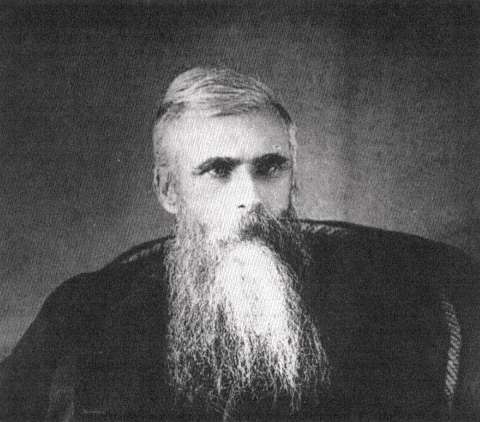

Charles Kohler, the German immigrant musician turned wine merchant who,

with his partner, John Frohling, first put the sale of California wine on a national

basis. The portrait is from about 1875, (Author's collection)

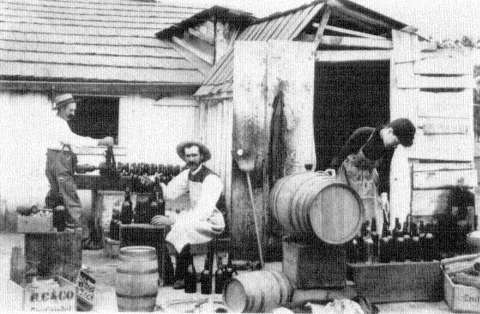

1856 from the United States Agricultural Society meeting in Philadelphia.[96] Their success was such that they almost at once dominated the Los Angeles wine trade, buying and crushing the produce of some 350 acres of vineyard each year. Their method was to send a crew from vineyard to vineyard, where some of the men would pick the grapes and others stem, crush, and press them. The whole wine-making process was thus entirely in the hands of the firm, even though they might be working on the property of other vintners—Wolfskill, or Keller, for example, with whom they had contracts. The Kohler & Frohling vintage crew, under the direct supervision of Frohling, is thus described in action at William Wolfskill's vineyard and winery in 1859:

He [Frohling] has in his employ four men who are cleaning off the stems; this they do by pushing the grapes through the sifter [a wire sieve] with their hands; two men turn the mill [of two grooved iron cylinders] by cranks; two feed the hopper; one weighs the

grapes; three or four attend to the wine as it comes from the mill and the presses; five or six do the pressing and carry off the pommace to the fermenting vats; one, two or three attend to washing, cleansing and sulphuring of grapes; and three teams are constantly employed in hauling the grapes. Every night all the presses and appliances used about them are all washed thoroughly to prevent acidity. Everything that comes in contact with the grape juice from the time the grape is bruised till it reaches the cask is kept as pure as abundance of water and hard scrubbing can make it.[97]

The year 1859 yielded a small vintage in Los Angeles, but even then Kohler & Frohling made more than 100,000 gallons. The next year was a poor one too, yet Frohling had to rent space from the city under the Los Angeles court house in order to accommodate all the wine he then had on hand. He advertised the place by first holding a harvest home celebration there; afterwards, he set up a bar to which thirsty Angelenos could go to buy a glassful of the young wine drawn from the 20,000 gallons reposing in the cool cellar.[98]

From the account of Frohling's winemaking methods in 1859, it is evident that he had an enlightened notion of how to do it at a time when others in Los Angeles were still using Indian foot-power. Frohling died in 1862, but the standards he set were maintained and the reputation of the firm made secure. Among other improvements, the firm of Kohler & Frohling brought in new varieties to the Los Angeles Valley, especially the varieties used for the production of port and sherry, and so helped to reduce the region's dependence on the unsatisfactory Mission.[99] In the history, not just of Los Angeles, but of the whole state of California with respect to winegrowing, Kohler and Frohling occupy a place of particular distinction. They showed the way the trade should go, and they deservedly prospered.

Los Angeles was where the grapes grew and the wine was made; San Francisco was, at first, the place where the wine was sold and drunk—130,000 gallons were shipped from south to north in 1861, for example, where it was Kohler's business to sell it.[100] The next and crucial step, as production grew, was to secure recognition outside of the state—no easy task when the Pacific Coast was still largely unpopulated and the western center of wine production was separated from the eastern centers of population by a continent uncrossed by road or railroad. Kohler & Frohling nevertheless began to make shipments to the east, and it is for that reason, especially, that the firm is important in the history of California wine. How soon it entered into out-of-state trade is not clear; it could not have been long after the beginnings, for by 1860 Kohler & Frohling had shipped over $70,000 worth out of California and had exclusive agencies in New York City and Boston, opened in that year.[101] In 1861 the Sainsevain brothers also opened a New York City branch,[102] and from this point the wines of California grew, more and more, to be the dominant element in the native wines that flowed through the country.

California wine—Los Angeles wine, really—was soberly examined and reported on by the gentlemen of the Farmer's Club, a section of the American Institute in New York City, in 1862, the earliest tasting notes on the state's wines made

outside California that I know of. The Sainsevains' white wines, under the Aliso label, received good marks. Their sparkling wine was highly praised too—"well fined, fermented in the bottle, is entirely clear and free from sediment, and is truly a good, sound, dry wine" at $13 a dozen; given the failure of the Sainsevain champagne to secure a market, the New Yorkers were evidently being more than kind in this judgment. The wines from Kohler & Frohling were not specifically identified in the published report, but perhaps they included the port, at $8 a dozen delivered in New York, and an angelica that did not please the taste of the New Yorkers—"it is too strong for a 'ladies' wine,' and a bottle full of it contains I don't know how many headaches," one judge concluded. But on the whole the examination was a success for the Californians: "I think the samples shown to-day," one taster declared, "prove that America is capable of producing its own wine, and that we are really independent of the wine countries of Europe."[103] This must have gratified Kohler, who, in 1857, had written to one of his Los Angeles correspondents complaining of competition and the difficulties of selling native wines, yet jauntily concluding that "on the long run we will beat Europe anyhow."[104]

When Mark Twain, newly famous as the author of the "Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," left California for New York in 1866, he took California wines with him to help promote them in the East.[105] He may have done some good, for by 1867 the shipments of California wine to New York for sale there and elsewhere in the East had reached impressive figures: 80,000 gallons of angelica, 150,000 gallons of Los Angeles port, and half a million gallons of white wine from Los Angeles and Sonoma (then the region second to Los Angeles in production) were said to have been shipped that year. These figures are, without doubt, on the inflated side, but even making a large allowance for hopeful exaggeration, they show that, as the writer who reports them put it, "the viniculturist of California has good prospects before him."[106] Ten years later Kohler & Frohling could boast that no town or city of middle size or more was without its wines, which included the following range of types (I follow Kohler's own enumeration): hock, riesling, muscat, tokay, gutedel, claret, zinfandel, malvoisie, burgundy, sherry, port, angelica. The firm, by that time, had permanent establishments in Sonoma and in St. Louis, in addition to its San Francisco and Los Angeles properties, and was crushing up to two and a half thousand tons of California grapes a year.[107]

California wines did not make an instant or uncontested capture of the eastern market for native wines; the producers in Ohio and New York had an interest to protect, and did not scruple to accuse the Californians of adulterating their wines and using fraudulent labels. The Cincinnati people were especially truculent, proclaiming that so-called California wine for sale in the East was in reality native eastern wine. According to Kohler's recollection, the president of the American Wine Growers' Association in Cincinnati "made himself prominent in circulating and reiterating this charge," but was at last compelled to recant.[108] Shipping costs, too, were an obvious disadvantage for the Californians, and so was the lack of bottles on the remote Pacific frontier. The last difficulty was much reduced by the

founding of the Pacific Glass Works in 1862; Kohler & Frohling had a one-sixth interest in this venture, and after it produced its first wine bottle in 1863 the firm had a secure source of supply.[109]

The later fortunes of Kohler & Frohling need not be recounted here. The firm survived, and even helped to direct, the shift of California's winemaking from south to north; as early as 1865 it had purchased a Sonoma County vineyard property. When Kohler, the immigrant violinist, died in 1887, he left to his sons an impressive estate: the largest wine merchant's firm in California and winegrowing properties in Los Angeles, Sonoma, Fresno, and Sacramento counties.[110] Kohler has been called "the Longworth of the west," and he may be allowed a clear claim to that modest title in virtue of his having been the first man to make a name for the wines of California outside the place of their origin, as Longworth had done for the wines of Cincinnati.

The Beginnings in Northern California

Winegrowing in northern California did not wait upon the Gold Rush, though of course that event transformed it. Like the southerners, the early settlers in the north had the winegrowing example of the missions before them—San Jose, Santa Clara, and Sonoma especially. The vineyards and wine production of these establishments were, however, much smaller than those of the missions to the south, and though their wines and brandy enjoyed a good reputation, they cannot have been in very great supply: the vineyard at Sonoma, for example, seems to have been less than an acre in extent, and of the two vineyards at Mission San Jose that survived secularization, the larger contained only 4,000 vines.[111]

The first layman to grow grapes in the north was, so far as the record goes, the original commandante of Alta California, and later the governor of the province, Pedro Fages, who planted a garden with vines at Monterey around 1783.[112] Despite this precocious beginning, however, winegrowing in the northern part of the state was very slow to spread and develop. There were vineyards here and there, of course, besides those of the missions. Kotzebue mentions the grapes of the pueblo of Santa Clara in 1824,[113] and later visitors to the place also remarked on the local vineyards. General Vallejo, who presided over the secularization of the mission at Sonoma in 1835, took over the mission's vineyard, located just off the plaza of the. tiny village he had founded there. In view of the later importance of Sonoma to the. California industry, much has been made of the importance of this beginning; it remained only a beginning, however, until after 1849. Sir George Simpson, the British administrator of the Hudson's Bay Company's territories and an intrepid explorer, visited Vallejo at Sonoma in 1841. The general had, Sir George wrote, a vineyard of only about three hundred square feet, inherited from the mission priests but replanted by Vallejo, yielding around 540 gallons of wine.[114]

Other growers in the north before 1849 were so few that almost all of them may be mentioned. George Yount, a mountain man who came to California with William Wolfskill and moved to the north, has the distinction of having planted the first grapes in the Napa Valley (where he had settled two years earlier, at what is now Yountville but was then the Caymus Rancho) in 1838. Yount's vines grew from cuttings taken from Vallejo's at the Sonoma Mission; Napa Valley wine, therefore, is originally derived from the Sonoma Valley, a fact that will give pleasure to the partisans of Sonoma in the rivalry between California's two best-known wine valleys.[115] Yount's beginning was followed by Dr. Edward Bale, an Englishman, who planted vines at his home north of St. Helena on a ranch he acquired in 1841 (he got it through Vallejo, whose niece he had married). Some time around 1846 Florentine Kellogg, a settler from Illinois, also planted grapes at St. Helena, as did Reason P. Tucker. To the north, in Tehama County, the county's pioneer settler, Peter Lassen, a Dane, set out a small vineyard in 1846 that was ultimately transformed into the huge Vina Vineyard of Leland Stanford later in the century.[116] To the east of Napa, in what is now Solano County, an outpost of southern California viticulture was established at the Rio de los Putos Rancho, the joint property of William Wolfskill and his brother John. John took up residence on the property in 1842 and set out a small vineyard of Mission grapes in the spring of 1843.[117]

In Contra Costa County, across Suisun Bay at the foot of Mount Diablo, Dr. John Marsh had a small vineyard in 1846, from which he made wine. Besides Mission vines he had Isabella and Catawba—a not uncommon circumstance in the early days. Easterners were familiar with their native grapes and were probably profoundly skeptical about vinifera's chances, even in a country where it was known to succeed. Marsh, a Yankee and a difficult man, was later murdered, so that his contribution to California's early winemaking history did not come to much.[118] A few more names make the list of early northern growers before the Gold Rush substantially complete: Nicholas Carriger, Jacob Leese, and Franklin Sears in Sonoma, Antonio Sunol and Juan Bernal in Santa Clara County.[119] Perhaps the most telling remark at this time is William Heath Davis's statement that, when in 1846 he gave an elaborate engagement party on board his merchant ship anchored in Monterey Bay, he served wine, but not local wine: "California wine was not in general use at that time as a beverage," he explains.[120] The southern part of the state was not yet exporting it with any regularity, and the north was not yet growing enough.

At the end of 1848 California is estimated to have had about 14,000 inhabitants, exclusive of Indians—probably the number was not really even that large. Four years later, after the crisis of gold at Sutter's Mill, the official state census recorded a population of 224,000.[121] The explosive rise in numbers is not exactly paralleled in viticulture, but it is certainly true that from 1849 onwards, winegrowing in California enters on a different order of magnitude from what it had known

72

The vines of the Coloma Vineyard went back to 1852, planted by the German Martin Allhoff

and the Scotsman Robert Chalmers. The winery was built by Allhoff, but on his death came

into the hands of Chalmers. This advertisement, from T. Hart Hyatt's Hand-Book of Grape

Culture (2d ed., 1876), is notable for the prominence still given to the old American hybrids

in California—Catawba, Isabella, and, perhaps, "Native (white and red)." (California State

University, Fresno, Library)