Nicholas Longworth and the Cincinnati Region

The defrauded settlers at Gallipolis, the nameless Frenchman making wine at Marietta, Rapp's Germans at Economy, Dufour's Swiss at Vevay, and all the other earliest winemaking settlers along the banks of the Ohio, from Pittsburgh almost to the junction with the Mississippi, were vindicated at last by the success of Nicholas Longworth at Cincinnati. As the main highway from east to west during the period of early settlement, the Ohio had inevitably seen repeated trials of viticulture, suggested by the combination of southward-facing slopes and broad waters. Dufour, as early as 1801, had assured Congress that the Ohio would rival the Rhine; it has never done so, but it was the scene of the first considerable wine production in this country, flourishing around Cincinnati from the early 1830s till after the Civil War, and unashamedly flaunting the naive slogan "The Rhineland of America."[1] An account of what lay behind this too-ready formula is instructive as to the chances and changes of commercial winegrowing in the era when useful native varieties had been found but before effective controls against diseases had been discovered.

The first person to plant a vineyard on the site now occupied by Cincinnati, on the great double curve of the Ohio, was a Frenchman named Francis Menissier, a political refugee who had once sat in the French parlement . At the end of the eighteenth century he laid out a small vineyard of vinifera on a slope of the new town (now the corner of Main and Third).[2] There he had success enough—or claimed that he had—to petition Congress in 1806 for a grant of land for vine growing on

the strength of his experiments.[3] The petition was denied, but Menissier's example was not lost.

In 1804 a young man named Nicholas Longworth (1782-1863) arrived in Cincinnati from Newark, New Jersey, to make his fortune in this new and burgeoning town, soon to be a city.[4] Longworth had already discovered a consuming interest in horticulture, but he put that aside while he studied law and began a successful practice. He soon found himself doing even better in land than in the law, and in no very long time he was recognized as having the true Midas touch: property that he bought for a song became worth millions, and Longworth joined John Jacob Astor as one of the two largest taxpayers in the United States. Longworth was a little man, and eccentric in dress, speech, and manner. But he was also strong-willed and successful, so that he could afford to do as he wished. By 1828 he was able to quit a regular business life and devote himself to his horticultural interests. These were fairly wide—he helped to establish the scientific culture of the strawberry, for ex-ample-but his first and most enduring love was the grape.

His attention was caught by the work of the Swiss at Vevay, and as early as 1813 Longworth had begun to experiment with grape growing in a backyard way—this was even before the return of Dufour from his long European sojourn.[5] His first commercial beginnings, in 1823,[6] were with the grape grown at Vevay, that is, the Cape or Alexander, which Longworth set out on a four-acre vineyard in Delhi township under the care of a German named Amen or Ammen. Longworth had the idea—a good one—that by making a white rather than a red wine from the Alexander he might get an article superior to that which the Swiss were selling along the Ohio. What he got, according to his own recollection, was a tolerable imitation of madeira, a white wine that required amelioration with added sugar and fortification with brandy.[7]

That was not what he wanted. The next step—again, as in the case of so many other pioneers, we recapitulate in miniature the general history of vine growing in America—was to try European varieties. He planted these by the thousands, from all sources, over a period of thirty years, and did not publicly repudiate the possibility of using vinifera until 1849.[8] He saw, however, that the development of good native varieties was the most important job to be done. He never faltered in that conviction, and even after his success with the wines of the Catawba, he continued to offer a $500 reward for a variety that would surpass that grape for winemaking.[9] He received and made trial of native vines from all over the United States, but did not succeed in finding a new variety to eclipse the Catawba.

Longworth's primary object was the production of an attractive dry table wine from the native grape, both in the name of "temperance" (already a rallying-cry among the moralists of the United States) and because such wine is the necessary basis of any sound winemaking industry in any country. The American idea of wine was, in Longworth's judgment, thoroughly corrupt: the wine favored by a public without a native winegrowing tradition, and long accustomed to rum and

38

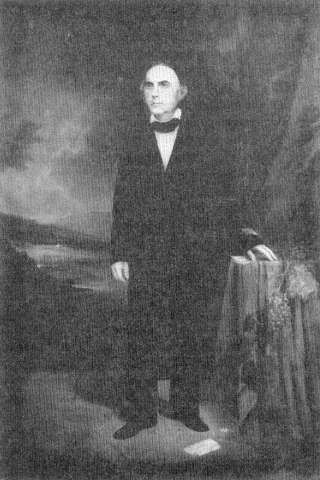

Nicholas Longworth (1782-1863), the man who made Cincinnati and the

banks of the Ohio the "Rhineland of America," at the height of his

reputation as the leading American winemaker. The Catawba grapes on

the table and the vineyards in the background are the emblems of

Longworth's achievement. (Portrait by Robert S. Duncanson, 1858;

Cincinnati Art Museum)

whiskey, generally contained 25 percent alcohol, and, Longworth added, "I have seen it contain forty percent."[10] After his unsatisfactory trials with the Alexander and with imported vinifera, Longworth got his chance when Major Adlum provided him with cuttings of the Catawba in 1825. Why Longworth should have been so slow to respond to this possibility I do not know: he must have known of the new grape as early as 1823, when Adlum began to publicize it. In any case, 1825 is the date of record.[11] Precisely when he got his first wines from the Catawba, is not clear. But by 1828, the year in which he retired to devote himself to wine-

growing, he was already well embarked on the plan with which he persisted through the rest of his life. Young Thomas Trollope, the brother of the novelist, who had accompanied his family to Cincinnati in 1828 on its hare-brained scheme for a frontier emporium selling exotic bijoux, made Longworth's acquaintance then and remembered him as "extremely willing to talk exclusively on schemes for the introduction of the vine into the Western States."[12] Young Trollope's mother, the redoubtable Frances, was quite unflattering about the wine of Cincinnati. A note to her Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832) provides what may be the first published judgment on Longworth's wines. It is not encouraging:

During my residence in America, I repeatedly tasted native wine from vineyards carefully cultivated, and on the fabrication of which a considerable degree of imported science had been bestowed; but the very best of it was miserable stuff. It should seem that Nature herself requires some centuries of schooling before she becomes perfectly accomplished in ministering to the luxuries of man, and, perhaps as there is no lack of sunshine, the champagne and Bordeaux of the Union may appear simultaneously with a Shakspeare, a Raphael, and a Mozart.[13]

The basis of Longworth's plan for viticulture was to make use of—or exploit—the labor of the German immigrants flowing into the Cincinnati region and giving it that German flavor that it still retains. When Trollope knew him, Longworth was employing Germans to cultivate vineyards on his own estate at a wage of a shilling a day (Trollope's figure) and food—a peonage advantageous to Longworth and perhaps tolerable to the new immigrants.[14] The Germans were in fact doubly necessary: they not only grew and made the wine, they drank it as well. The dry white catawba that Longworth succeeded in making was unappreciated by Americans used to sweeter and more potent confections; Longworth used to tell about how even the choicest Rheingaus were mistaken by American tasters for cider or even vinegar. The Germans, however, were better instructed, and for many years, Longworth wrote, "all the wine made at my vineyards, has been sold at our German coffee-houses, and drank in our city."[15]

Like all American winegrowers before him and afterwards, Longworth was troubled by the tendency of Americans to prefer wines with European names to those that were honestly, but too adventurously, given names that meant nothing to an uninstructed consumer: "catawba" was dubious at best; "hock" meant familiarity and security. So, at some time in the 1830s, he wickedly put counterfeit labels on his bottles of catawba: Ganz Vorzuglicher (Entirely Superior); Berg Tusculum (Mount Tusculum, after the actual name of one of his vineyard sites); and Versichert (Guaranteed).[16] He did not actually put these labels on the market, but they helped to make his point—still a familiar one—that there were many who could not abide native wine under its own label but who acclaimed it under a foreign one.

Longworth continued, as he had begun, with his system of using German labor, though the terms became more liberal than those described by Trollope in 1828. Typically, Longworth sought to settle a German Weinbauer on a small

39

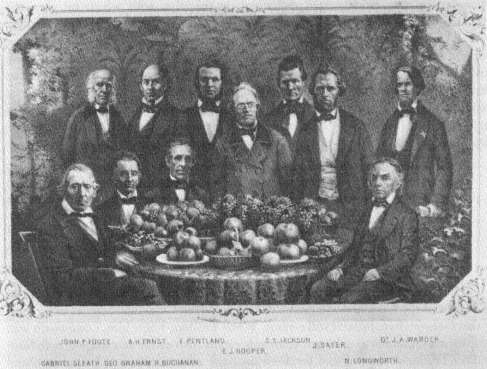

Members of the Cincinnati Horticultural Society, founded in 1843. At least three of these men—

Dr. J. A. Warder, Robert Buchanan, and Nicholas Longworth—were leading wine-growers in

Cincinnati. Note the grapes prominent among the fruits displayed on the table. (Cincinnati

Historical Society)

patch—four acres at most—and to leave him to himself to plant and cultivate. When a crop came in, Longworth would buy the grapes or the must or the vane, and split the profits with his tenant.[17] As the business developed, more and more of the processing went on under Longworth's own control, but the growing continued to be the business of the Germans, who had, as he said, been "bred from their infancy to the cultivation of the vine."

Longworth's earliest public account of his work in winegrowing appears to be an essay he contributed to a local compendium of agricultural advice published in Cincinnati in 1830, in which he urged that silk culture, the perennial rival of viticulture in the American dream, ought to be postponed in favor of the grape, and gave his own experience as his reason for thinking so.[18] In succeeding years the increasing number, frequency, and prominence of his contributions to the press on winegrowing provide an approximate measure of his growing success and recognition. His writings remained irregular and scattered, usually taking the form of letters addressed to particular topics, but they helped to make him the best-known and most frequently consulted expert on the subject of wine in his generation.

Longworth's scale of operations remained small through the 1830s; in 1833, for example, when he took the County Fair prize for his "pure Catawba," the produce of the nine scattered vineyards on which he had tenants was only fifty barrels, or about 3,000 gallons.[19] The development of viticulture in the ensuing ten years is witnessed by the establishment of the Cincinnati Horticultural Society in 1843; it at once took an interest in winegrowing, and made its first report on the subject in the year of its founding.[20]

The explosive expansion of the industry occurred after 1842, when Longworth, quite by accident, produced a sparkling catawba (as it was always called: never "champagne").[21] Even if he did not know how to make one, Longworth decided that a sparkling wine would be his means of opening a market beyond the Weinstuben of Cincinnati. After trying and failing to duplicate his first accidental success, he sent for a Frenchman in 1845. Unluckily, the poor man drowned in the Ohio before he could apply the secrets of his knowledge. Longworth found a successor, who commenced his work in 1847. Though the winemaker was French, Longworth was quite firm about his intent to develop a native wine. "I shall not attempt to imitate any of the sparkling wines of Europe," he wrote in 1849; instead, he aimed to provide "a pure article having the peculiar flavor of our native grape."[22]

By 1848 Longworth had built a 40' x 50' cellar expressly for the production and storage of sparkling catawba; by 1850 he was turning out 60,000 bottles a year and had plans for national distribution of his wine. This he began in 1852, by which year he had two cellars devoted to his sparkling wine, and a production of around 75,000 bottles.[23] The wine was made by the traditional méthode champenoise , in which, after a dose of sugar was added to the wine following its first fermentation, a second fermentation was carried out in the bottles, and the resulting sediment cleared by the tedious process of hand riddling. Losses from bottles bursting under the intense pressure of fermentation were sometimes catastrophically high: when 42,000 of 50,000 bottles were thus lost in a season, Longworth naturally wondered whether it was worth continuing.[24] Something, however, was saved from these losses by distilling the spilled wine into catawba brandy, as a brochure put out by Longworth's firm innocently admits.[25]

A third cellar manager, one Fournier, from Rheims, arrived in 1851 and did better.[26] The troubles and losses of the first years were rewarded; if Americans had been put off by the tart, dry taste of still catawba, they knew without instruction how to be pleased by bubbles. Suddenly, Cincinnati's winegrowers, and Longworth in particular, had a national winner, a widely advertised and widely enjoyed proof that the United States could produce an acceptable wine.

Longworth thoroughly understood the value of advertising. His letters to the press were progress reports on the promising development of his enterprise. He sent his wine to editors and to the competitions of horticultural and state agricultural societies: as early as 1846 he was exhibiting samples of catawba at the annual fair of the American Institute in New York City.[27] In common with a number of other Cincinnati producers, he sent samples of his wine to the Great Exhibition of

1851 in London, the original ancestor of and the model for all subsequent international exhibitions and fairs. The produce of native American grapes was, of course, powerfully strange to British palates; as the official Catalogue of the Exhibition politely remarked, "With many persons the taste for [catawba] is very soon acquired, with others it requires considerable time."[28] The publicity was bound to be helpful back in the United States. One of the great sensations of the Exhibition, the demurely naked Greek Slave of the American sculptor Hiram Powers, was the source of immense national pride in the United States when it was known that the British admired the piece. Powers, as it happened, was a Cincinnati boy whose first patron had been Longworth, another well-publicized fact that helped put Longworth in an attractive light—was he not domesticating both Bacchus and the Muses?[29]

Longworth also sent samples of his wine to eminent men as a way of promoting it. Powers, in Italy, was a useful agent in presenting catawba to politely interested Italians. Perhaps it was during his years in Italy that the poet Robert Browning heard of catawba wine. He knew of it, at any rate, for it is referred to in his curious poem "Mr. Sludge, the Medium" (1864).[30] Longworth made a lucky hit with the poet Longfellow, who responded to a gift of sparkling catawba with some hasty verses (injudiciously included in his collected poems) that have often been reprinted since. A very few lines are enough to show such merit as the poem possesses:

Very good in its way

Is the Verzenay

Or the Sillery soft and creamy;

But Catawba wine

Has a taste more divine,

More dulcet, delicious, and dreamy.

There grows no vine

By the haunted Rhine

By Danube or Guadalquivir,

Nor on island or cape

That bears such a grape

As grows by the Beautiful River.[31]

In 1855 Longworth was able to boast that he had sent a few cases of his wine to London, where it had been successfully sold in the regular way of trade.[32] By this time, Longworth, his large house called Belmont, on Pike Street, adorned with the work of Powers, and his vineyards on a hill (now part of Eden Park) had long beer established as premier attractions among the sights of Cincinnati, to be exhibited to all the many interested travellers who made their way to the Queen City of the Ohio before the Civil War.[33] Longworth was a national figure, celebrated for his wealth, his wine, and, most of all, for being a "character," shabbily dressed, la—conic, unpredictable, and—according to the press at any rate—prodigal of charity. The English journalist Charles Mackay, travelling through the United States as the correspondent of the Illustrated London News in 1858, will do to represent many

40

Longworth's vineyards recorded in 1858, perhaps more after the fashion of European models than as

unadorned documentary truth. The steamboat and the train represent American progress, but the style

of the vendangeurs and vendangeuses is distinctly Old World, as is the single-stake training of the vines,

like that practiced on the Moselle and the Rhine. (From Harper's Weekly . 24 July 1858)

others. Cincinnati did not impress him as quite so enlightened a place as its inhabitants liked to think; as they had been to Mrs. Trollope thirty years earlier, pigs were too much in evidence for Mackay's taste, those pigs that, barreled as pickled pork and shipped up and down the river, gave Cincinnati the name of Porkopolis and made it wealthy. Longworth and his wine moved Mackay's unreserved admiration, however; dry catawba, he reported to the English, was better than any hock, and sparkling catawba better than anything coming from Rheims. When prose seemed inadequate to his rapture, Mackay (a facile song writer) broke forth into verse:

Ohio's green hilltops

Grow bright in the sun

And yield us more treasure

Than Rhine or Garonne;

They give us Catawba,

The pure and the true,

As radiant as sunlight,

As soft as the dew.[34]

Not everyone was so well pleased by Cincinnati's wines: the native character of the Catawba, its labrusca foxiness, was a shock to any uninitiated taste, and some visitors were candid enough to say so. When the Englishwoman Isabella

41

A menu from the Gibson House, Cincinnati, dated 15 November 1856.

Sparkling Catawba from the local vineyards is listed on the same terms

as some distinguished grandes marques from Champagne; so, too,

among the "Hocks," one finds "Buchanan's Catawba" listed along

with Marcobrunner and Rudesheimer. (California State University,

Fresno, Library)

Trotter and her husband visited Cincinnati in 1858, almost at the same time as the well-disposed Mackay had been entertained there, they were regaled by their hosts with "most copious supplies of their beloved Catawba champagne, which we do not love, for it tastes, to our uninitiated palates, little better than cider. It was served in a large red punch-bowl of Bohemian glass in the form of Catawba cobbler, which I thought improved it."[35] To balance the record, one may quote a more enthusiastic description of catawba cobbler, provided by the Cincinnati wine-grower W. J. Flagg. The wine, he says, should be young, and sugar and ice added

to it help to temper the heat of an Ohio valley summer: "A cobbler of new wine, grown in the valley of the Ohio, or Missouri, where the Catawba ripens almost to blackness, drunk when the dog-star rages, lingers in memory for life."[36]

Longworth was always the leading name in Cincinnati winemaking, and sparkling catawba was always the glamorous item. But they could not have long stood alone, and in fact a supporting industry developed quickly. Longworth's part of the whole diminished in proportion as others set up and began to develop their vineyards and wineries. In 1848 there were 300 acres planted, of which 100 were Longworth's; in 1852, there were 1,200, distributed among nearly 300 proprietors and tenants. In 1859, perhaps the peak year in the history of Cincinnati wine-growing, some 2,000 acres produced 568,000 gallons of wine, putting Ohio at the head of the nation's wine production.[37] Almost all of this was white, and almost all from the Catawba, which was now indisputably confirmed as the grape of the region. But it did not quite exclude all its rivals. In 1854, at the New York Exhibition of that year, it was Longworth's sparkling Isabella that took the highest award among American wines.[38]

Among the early growers who followed Longworth into viticulture were Robert Buchanan, John Mottier, William Pesor, C.W. Elliott, A. H. Ernst, and a string of doctors: Stephen Mosher, Louis Rehfuss, and John Aston Warder, the last-named becoming later one of the country's most distinguished horticulturists. Not all of them were actual Cincinnatians; at least, not all of them confined their activity to Cincinnati proper. Dr. Mosher, for example, lived and grew his grapes on the Kentucky side of the river, as did others, including the actor Edwin Forrest.[39] Other vineyards in Ohio lay outside Hamilton County, in which Cincinnati stands; vineyards flourished in Brown and Clermont counties, and extended down the river well into Indiana at least in a minor way, and sometimes in more than a minor way. Clark County, Indiana, across the river from Louisville, had 200 acres of Catawba by 1850, and the calculations of the production along the Ohio included the grapes of Kentucky and Indiana as significant additions to those of the immediate Cincinnati region.[40]

Like Longworth, most of the Ohio River proprietors seem to have relied upon tenants, German by choice, to perform the labor in the vineyards (and then it was usually the woman rather than the man who did the work, as Longworth was fond of pointing out).[41] At this uncertain stage, only a man who had other resources could sustain the vicissitudes of such a pioneering enterprise. The actual wine-making was carried out on the tenanted properties in the early days, with predictably uneven results. As production rose, and the reputation of the wine began to be established, winemaking came increasingly under the control of commercial houses whose business it was to perform the vinification, storage, and distribution of the wine. By 1854 Longworth had two such houses; over his main cellars he had built a sort of barracks, four stories high, where poor laborers and their families might live. They showed their gratitude by frequently breaking into the wine vaults below and stealing their landlord's choicest wine, or so it was reported.[42]

42

A winery on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River, in the region of Cincinnati. The vintage

scene in this picture is described thus: "The grapes, when fully ripe, are gathered in baskets

containing about a bushel, as well as in a sort of 'pannier' of wood, made very light and strong,

and which is supported by straps or thongs of willow, on the back of the picker; . . . they are

brought from the vineyard in this manner and thrown upon the picking tables, where they are

carefully assorted." (Western Horticultural Review I [1850])

Other négociants , as the French would call them, were G. and P. Bogen, Zimmerman and Co. (associated with Longworth), Dr. Louis Rehfuss, and, in Latonia, Ken—tucky, the firm of Messrs. Corneau and Son at their Cornucopia Vineyard, some four miles south of Covington, across the river from Cincinnati. The figures for 1853, a good year, give some idea of the scale of production. The commercia! houses bottled 245,000 bottles of sparkling wine in that year, and 205,000 of stil wine, the value of the whole being estimated at $400,000 at prices ranging from $1.50 a bottle for the finest sparkling wine to 40 cents a gallon for the lowest quality table wine.[43]

The accounts of winemaking methods in Cincinnati show that the general practice in the 1850s was excellent. Longworth himself was emphatic about the necessity of making "natural" wines and confident of his ability to do so. He set a good example. Grapes were picked at full maturity, and all green or unsound berries were removed from the bunches by hand. The grapes were then stemmed

43

Michael Werk, an Alsatian who prospered by making soap and candles in Cincinnati,

joined the growing number of Cincinnati vineyardists in 1847. In less than a decade he

was taking prizes for his wines. Later, when disease threatened to extinguish the Cincinnati

vineyards, Werk developed large vineyards on the Lake Erie shore and then on Middle

Bass Island in Lake Erie. (Cozzens ' Wine Press , 20 August 1856; California State University,

Fresno, Library)

and crushed, and the juice fermented without the addition of sugar whenever possible. The French technique of rubbing the bunches over wooden grids in order to remove the stems was introduced by 1850.[44] The hydrometer was a standard tool, so that the winemaker knew whether he had sufficient sugar to insure a sound fermentation; if not, then the addition of sugar before fermentation was allowed. "allowed" by local agreement as to its utility, that is; we are talking about an in-

dustry in its Innocent Age, wholly unregulated and subject only to its own sweet will. Modern producers and dealers may try to imagine what that condition is like. The juice was fermented at low temperatures, under water seal, and quickly racked from its lees, without undue oxidation, and then stored in clean casks in cool cellars.[45] Modern technology could not prescribe better methods, so far as they went. One irregularity Longworth did, it was whispered, allow himself. He was convinced that Americans were partial to the "muscadine" flavor of rotundifolia grapes. In order to get it he bought large quantities of Scuppernong juice in the Pamlico and Albemarle regions of North Carolina and added that to flavor his Ohio catawba.[46] In the spring the wine may have undergone a malo-lactic fermentation, and then was ready for bottling. There was then, as there is now, some disagreement as to the proper length of aging for white wine. Longworth favored a long time in the wood, keeping his superior wines for four or five years. Others thought that a year in cask was enough: "There are many who think the Catawba wine is better at this period than ever afterwards" is how the writer in the U.S. Patent Office Report for 1850 puts it.[47]

Cincinnati wine may be said to have come of age at the beginning of the 1850s. The commercial wine houses, insuring the stability and distribution of the region's produce, were founded then. In 1851 the growers met in Cincinnati and organized the grandly named American Wine Growers' Association of Cincinnati. Its objects were to publish information useful to growers through its journal, the Western Horticultural Review , and to promote the interest of the industry generally, especially by insuring that only pure, natural wine was sent to the market.[48] The association sponsored a "Longworth Cup," awarded annually to the producer of that year's best catawba,[49] and was the first such organization concerned with wines and vines in this country that is entitled to be called an industry organization.[50]

At the Great Exhibition in London, to which, as has already been mentioned, the growers of Cincinnati made a respectable contribution, the official Catalogue explained that Cincinnati was now the "chief seat of wine manufacture in the United States" and that though yet in its infancy, the trade was "attracting much attention, and growing in importance in America."[51] In vindication of the claim, five producers besides Longworth exhibited specimens of catawba wine: Buchanan, Corneau and Son, Thomas H. Yeatman, C. A. Schumann, and H. Duhme. Yeatman, who took a prize for his wine in London, made visits to the vineyards and wine estates of France, Germany, and Switzerland in 1851 and 1852 in order to study European methods.[52] Longworth sent both catawba and unspecified "other wines" to the Exhibition—a reminder that he never ceased experimenting with alternatives to the Catawba grape in hopes of finding a variety without its defects. In the year following the Exhibition, Longworth began the promotion of his wine on a countrywide basis,[53] and with that event the wine of the Rhineland of America may be said to have arrived.

Cincinnati wine had only a very fragile tenure, however, more fragile than was yet recognized, though of course sensible men understood that the obstacles to be

44

The label of T. H. Yeatman, from he year in which his wine took a prize

at the Great Exhibition, London. (Western Horticultural Review 1 [1851])

surmounted were considerable. Robert Buchanan, for example, a successful Cincinnati merchant who began growing grapes in 1843, and who, with Longworth, was a founder of the Cincinnati Horticultural Society and a scientific student of viticulture and winemaking, took a modest view of what he and his fellows had accomplished. In his little Treatise on Grape Culture in Vineyards, in the Vicinity of Cincinnati (1850), the best practical handbook that had yet appeared on the subject in the United States, he wrote simply that "we have much to learn yet in the art of making wines."[54] But, as we have seen, the general principles of production at Cincinnati were in fact quite sound. The real—and soon fatal—weakness in the industry lay in the vine growing rather than in the winemaking. The Catawba did not always ripen well, and the average production was not very large; it seems to have run around one and a half tons per acre, though production as high as four tons was known, and ten was claimed.

Most ominous was the damage done by diseases, powdery mildew and black rot chief among them. In the first years of Catawba growing, these diseases were

45

Robert Buchanan's little book, first published anonymously, is one of the earliest and

best accounts of winegrowing around Cincinnati. Buchanan, a Cincinnati merchant,

had had a vineyard since 1843. His book, which went through seven editions in the

next ten years, was unlike any of its American predecessors in being based on the

practices of an established industry. No writer in this country before Buchanan had

had that advantage. (California State University, Fresno, Library)

only a minor problem in the Cincinnati region, so that the early confident assurances of the unchecked profits to be made by viticulture seemed perfectly justified. But the growth of planting and the passage of years saw mildew and black rot increasingly more frequent, as they had a homogeneous and extensive population of grapes to work upon. The record of each successive year's vintage, so far as this can be reconstructed, shows alarming ups and downs according to the lightness or the heaviness with which the infestations, especially black rot, struck the vineyards in a given year.[55] Even before 1850 black rot and mildew were evident, and the growers were unable to take any action against them. The fungous character of the rot was not generally understood—some attributed the disease to worms, some to cultivating methods, others to the atmosphere or to a wrongly chosen soil[56] —and so when the Catawba, a variety peculiarly susceptible, was touched by the blight, all that men could do was to resign themselves to their loss and speculate on the causes and cures.

Among the other diseases that attacked Ohio grapes, powdery mildew was the most important after black rot. This disease, native to the United States, first attracted serious attention not in its native place but after it had been exported to the Old World. In the 1850s Madeira saw its vines, upon which nearly the whole population depended, ravaged by powdery mildew (generally called oidium in Europe). The people of the island, driven to starvation, were forced to abandon their homes and to emigrate in large numbers. The island's wine trade has never fully recovered from the catastrophe—made more bitter still by the fact that it came from the country where Madeira's wines were held in esteem beyond all others. But Madeira was only the worst-afflicted among many: Portugal, Spain, France, and Italy suffered too. In Italy, the appearance of the disease coincided with that of the first railroads. Peasants, putting these things together, blocked new construction and tore up miles of rails already laid in order to fight the disease.[57]

The control of powdery mildew by sulfur dusting was now successfully tested and developed in Europe, but it did little for the growers of Cincinnati. Native vines, unlike vinifera, are sometimes injured by sulfur, so the cure in this case might not have been much preferable to the disease. Against black rot, even the most perfect application of sulfur would have had no effect. For that disease the effective treatment is a compound of copper sulphate and lime called bordeaux mixture, and that was not developed until 1885, much too late to be of use to the growers of Cincinnati.

Throughout the 1850s rot and mildew were increasingly present in the vineyards of Cincinnati. In that decade, only three good years—1853, 1858, and 1859—were granted to the growers by weather conditions inhibiting the rot.[58] By the end of the decade it was clear that the very existence of the industry was now problematical, for who could endure such helplessness and such uncertainty? Some efforts were made to introduce different and more resistant varieties—the Delaware, for example, seemed at one time to promise a better basis for viticulture, but it did not fulfill the promise. Ives' Seedling, a local introduction that had gained the premium

offered by Longworth's Wine House for the "best wine grape for the United States," also had some vogue, but was not good enough for wine or resistant enough to disease to provide a new basis for the trade.[59] The outbreak of the Civil War reinforced and accelerated the process begun by diseases. Though shortages brought high prices for wine, the vineyards were neglected, and new plantings ceased. A visitor to Cincinnati in 1867 reported that "the wine culture" was "somewhat out of favor at present among the farmers of Ohio."[60] By 1870 the vineyards, though still occupying a substantial acreage, were largely moribund. In that year, the brief flourishing of the Rhineland of America came to a symbolic close when Longworth's wine-bottling warehouse was taken over by an oil refinery.[61]

Longworth himself lived long enough to see the end coming, but refused to admit its certainty. As W.J. Flagg, his son-in-law and the manager of his wine business, wrote of Longworth at the end: "It was well enough he should pass away without knowing how nearly had failed the great work of his life. Among his last words before losing consciousness was an inquiry if [Flagg] had arrived: he wanted to tell him, he said, of a new vine he had found which would neither mildew nor rot. He never found it in this world."[62] The extinction of viticulture around Cincinnati was complete, and so powerful was the effect of the failure that even when, later, it became possible to control the diseases that had overwhelmed the vineyards, no one came forward to take the opportunity. Only in very recent years have tentative efforts been made to revive the industry there: more than a century has been needlessly lost in the interval.

Yet there had , after all, been a flourishing winemaking industry in Cincinnati: to show the possibility of such a thing was the historical importance of Longworth and his fellow growers. After many years of loss, Longworth had, before the end, even made money from winegrowing, and the possibility of doing so again waited only upon better cultivars and effective fungicides.

Meantime, the Cincinnati region had generated a sort of colonial extension of itself upon the shores and islands of Lake Erie, two hundred miles to the north. As early as 1830 a gentleman named H. O. Coit was growing vines and making wine in Cleveland, and he prophesied then that the shores of Lake Erie would someday be famous for their vineyards.[63] The success of viticulture along the Ohio River stimulated experiment with Catawba and other varieties along the lake shore in the 1830s. But it was not until late in the 1840s that anything like a commercial scale of viticulture was approached in this region. Northern Ohio had two centers of grape growing, from Cleveland eastward to the Pennsylvania border on one side of the state, and around Sandusky and the Lake Erie Islands on the other. It was in the second of these that winemaking particularly flourished. Here it was discovered that an ideal matching of variety and site had been stumbled upon: the limestone soil of lake shore and islands is classic grape-growing soil; the delayed springs and protracted autumns that the moderating effect of the lake brings to the islands just suited the Catawba; there, too, the diseases that destroyed the Catawba along the Ohio River did not pursue it with the same destructive effects. There has been an

46

Not all Ohio winegrowing was confined to Cincinnati or to the Lake Erie shores; this undated

(c, 1850) trade circular offers altar wine from Martin's Ferry in far southeastern Ohio, just across

the river from Wheeling, West Virginia. Noah Zane, the founder of Wheeling, is credited with

having introduced grape culture to the region. (California State University, Fresno, Library)

uninterrupted history of Catawba growing on Kelley's Island and the Bass Islands since the first vineyards were set out, a record of continuity unmatched in the erratic history of American viticulture.[64]

So long as the Cincinnati region prospered, development along Lake Erie was not notably rapid. The boom commenced as the Cincinnati industry declined: large plantings began just before 1860, and the years 1860-70 were remembered as the era of "grape fever."[65] Seven thousand acres had been planted by 1867, and though growth inevitably slowed, there were 33,000 acres in Ohio by 1889, most of it in the Lake Erie counties. The growers, as at Cincinnati, were largely Germans; indeed, some of them were Cincinnati Germans looking for alternatives to the disease-ridden banks of the Ohio.[66]