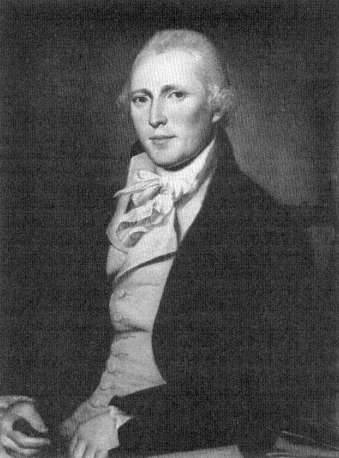

John Adlum, "Father of American Viticulture"

It is now time to take up a story of success, the episode that is traditionally identified as the true beginning of commercial winegrowing as it developed in the eastern United States. The man who is familiarly called the "Father of American Viticulture"—how well-deserved that title is will appear from this sketch of his work—was Major John Adlum (1759-1836), of The Vineyard, Georgetown, District of Columbia.[48] Adlum was born in York, Pennsylvania, and as a boy of seventeen marched off with a company of Pennsylvania volunteers to join the Revolution, but was captured by the British at New York and sent back home. Though he later held commissions in the provisional army raised in 1799, from which he derived his title of major, and in the emergency forces raised in the War of 1812, Adlum, after his brief experience of war, took up surveying as a profession. He chose a good time, for after the Revolution the western lands of Pennsylvania and New York filled up rapidly, allowing Adlum to make a modest fortune through the ready combination of surveying and land speculation. By 1798 he was able to retire, and he settled then on a farm near Havre de Grace, Maryland, at the mouth of the Susquehanna River, along whose course he had often travelled in his surveying work. He probably planted a vineyard at once at Havre de Grace, for he seems to have been interested in grapes even before his retirement; while carrying out his surveys he took notes on the native grapes growing wild in the woods and along the streams of Pennsylvania—red and white grapes growing on an island of the Allegheny, black grapes at Presque Isle, where the French were said to have made wine from them, and black grapes along the Susquehanna all came under his notice and suggested that, from such fruit, "excellent wines may be made in a great many parts of our Country."[49]

Nevertheless, his first plantings were of European vines, evidence of the strength of the grip that, at this late date in American experience, the foreign vine still had upon the minds of American growers. It did not take Adlum long, however, to decide that he had made a mistake. When insects and diseases overwhelmed his vinifera vines, he had them grubbed up and planted native vines instead.[50]

One of these was the Alexander, and from it Adlum succeeded in making a wine that had a significant success—he later admitted that his method with that batch was an accident that he could never afterwards duplicate.[51] Nevertheless, he made the most of what he had, which was, in the first place, an astute sense of publicity; he sent samples of his wine to the places and persons where they might have their most effective result. One went to President Jefferson, and with him the

34

John Adlum (1759-1836), whose Georgetown vineyard produced the first commercial

wine in the settled regions of the country. Adlum gave a tremendous boost to the

development of winegrowing by his introduction of the Catawba grape and by his

publications on grape growing and winemaking in the 1820s. (Portrait attributed to

Charles Willson Peale, c. 1794; State Museum of Pennsylvania / Pennsylvania

Historical and Museum Commission)

wine made a home shot. It was, the president wrote, a fine wine, comparable to a Chambertin, and he advised that Adlum look no farther for a suitable wine grape but press on with the cultivation of the Alexander. He should forget about foreign vines, "which it will take centuries to adapt to our soil and climate."[52] Adlum agreed, but observed with the doubtfulness of experience that Americans were not yet quite ready for wine from American grapes—as soon as they knew what they were drinking, they objected to it, though they might have been praising it a moment before.[53] The remark is one the truth of which most eastern winemakers even today will regretfully assent to. But Adlum was determined to persist, even though

he knew that, as a prophet of American wine, his own country would likely be the last to honor him.

In 1816 Jefferson wrote again to Adlum, having been stirred by a fresh prospect of planting wine vines, and learned that great changes had occurred in his correspondent's circumstances. Adlum was now living in Georgetown, on property near Rock Creek, above the Potomac, where he had settled after leaving Havre de Grace in 1814.[54] At the time of Jefferson's letter, Adlum had not yet set out a Georgetown vineyard. It may have been Jefferson's inquiry that aroused Adlum again; it may have been that Adlum had the thought in mind himself; in any case, he was soon back at planting vines, this time on a different basis and with a wholly different success.

The Vineyard, as he called his farm, was a property of some 200 acres; the vineyards themselves were on the south slope of a hill running down to Rock Creek, now part of Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C. A poetically inclined visitor in the early days found that they made a quiet, sequestered scene; rows of vines, ranged one above the other, rose from the base of a hill washed by a willow-fringed stream, beside which a black vine dresser gathered willow twigs for tying up the shoots of the vines that lined the hill above.[55] The picture is attractively idyllic, but perhaps a bit en beau . What Adlum had was in fact quite a modest establishment, with nothing of the grand château about it: from the vantage of another observer, the vineyard was seen as a "patch of wild and scraggy looking vines; the soil was artificially prepared, not with rich compost, but with pebbles and pounded oyster-shells."[56] The whole property was not large, and the vines occupied but a small part of the whole—some four acres by 1822.[57]

The first vintage at Georgetown of which we have report was made in 1822 and consisted of 400 gallons, in no way distinguishable from other vintages yielded by native vines before.[58] There was this difference, though: it was the produce of the nation's capital, and therefore noticeable and promotable in a way that, for example, the vintages of Dufour's Swiss on the remote banks of the Ohio were not. Here, for example, is how the editor of the American Farmer , a superior publication emanating from Baltimore, greeted Adlum's first offering:

Fourth of July Parties

Would manifest their patriotism by taking out a portion of American wine, manufactured by Major Adlum of the District of Columbia. It may be had in varieties of Messrs. Marple and Williams, and the Editor of the American Farmer will be thankful for the candid opinion of connoisseurs concerning its qualities.[59]

If any patriot-connoisseurs heeded the request, their responses do not appear in the American Farmer , but the publicity can have done Adlum no harm. Yet one wonders what Adlum could have been offering? July is too early by any stretch of the imagination for the vintage of 1822 to have been put on sale. And in any case, Adlum wrote to the American Farmer on 17 September 1822 that he had just then completed his winemaking.[60] The vintage of 1821, we know from Adlum's testi-

mony, had all turned to vinegar.[61] Possibly wine from 1820 was what was advertised in 1822, but there is no record of any production in 1820.

As Adlum himself explained in the American Farmer , in 1822, he had only just begun his work then: he had some vines of "Constantia" and some vines of what he called "Tokay"—not anything like real Tokay, as we shall see, but something portentous nonetheless. He had cuttings for sale, Adlum added, and he hoped himself to have some ten acres in vines soon.[62]

In the next year, Adlum's work was translated to a different plane. His "Tokay" had fruited for the first time in 1822, and the wine that he had made from it in that season developed into something better than any native grape had yielded before. Adlum lost no time in advertising his success, and, as others began to admire, he did not let any consideration of modesty restrain his high claims for the quality of the "Tokay" grape. Jefferson, of course, was one of the first to receive a bottle of Adlum's Tokay; James Madison was another.[63] Jefferson's reply, though polite, must have been a disappointment to Adlum, who may have hoped for something as extravagant as the great man's earlier comparison of Alexander wine to Chambertin. This time, Jefferson restricted himself to the observation that the Tokay was "truly a fine wine of high flavor."[64] That was good enough for promotional purposes; Adlum sent Jefferson's letter (and a bottle of Tokay) to the editor of the American Farmer , where a notice appeared in the next month. Later, Adlum reproduced Jefferson's letter in facsimile as the frontispiece of his book on winegrowing.

The history of the "Tokay" grape, which thus first came to public notice in 1823, is fairly circumstantial, though a number of questions remain as to its origin and early distribution. In sending a bottle to Jefferson, Adlum stated that the vine came from a Mrs. Scholl in Clarksburgh, Maryland, that a German priest had said the vine was "the true Tokay" of Hungary, but that Mr. Scholl (now dead) had always called it the Catawba.[65]

Adlum took cuttings from Mrs. Scholl's vine in the spring of 1819; by 1825 he had determined that "Tokay" was a misnomer, and reverted to the late Mr. Scholl's name, Catawba,[66] which belongs to a river rising in western North Carolina and flowing into South Carolina. Traditionally the grape was found first not far from present-day Asheville, in a region of poor, thinly timbered soil. Whether Scholl had any information to justify the name he gave the grape is not known. After the success of the grape had led to its wide distribution, a good many different stories about its origin were published, but none authoritative enough to settle the matter.[67]

The same uncertainty attends the botanical classification of the Catawba. Early writers called it a labrusca; Hedrick agrees, but adds that it must have a strain of vinifera as well.[68] It has the self-fertile flowers of vinifera, a trait that combines with its improved fruit quality to confirm its vinifera inheritance. As to the character of the grape, that is well established. After more than a century and a half of cultivation, it still remains one of the important native eastern hybrids; for winemaking, it is one of the three or four most valuable of such grapes. The fruit of the Catawbâ is

35

The Catawba grape, introduced by John Adlum in the early 1820s, the first

native hybrid to make a wine of attractive quality. Its origins are uncertain,

but after more than a century and a half of cultivation, it still retains a place

in eastern viticulture. (Painting by C. L. Fleischman, 1867; National Agricultural

Library)

a most attractive lilac, a light purplish-red, yielding a white juice which is definitely foxy, after the nature of its labrusca parent, but which may be transformed into a still white wine that Philip Wagner describes as "dry to the point of austerity" and having "a very clean flavor and a curious, special, spicy aroma."[69] Its superiority to the other grapes available in its day quickly led to its trial all over the inhabited sections of the United States; growers then learned that it presented some severe problems, being susceptible to fungus diseases and, in northern regions, failing to ripen except in special locations. It found a home in Ohio, first along the Ohio

36

John Adlum's was the first book on winegrowing to be published in the United

States as opposed to the British North American colonies. It was also the first

book to assume that American winegrowing would have to be based on native

American varieties. Both facts give the Memoir a special status in the early literature

of American winegrowing. (Huntington Library)

River and later in the Lake Erie district, and in New York in the Finger Lakes country. It remains, in both states, a staple grape for winemaking, particularly in the production of sparkling wine.

From the evidence of his own descriptions of his winemaking methods, and from the remarks of some critics, it appears that Adlum himself did not make very good wine from his Catawba. Though he disapproved of the established American practice of adding brandy (most often fruit brandy of local production) to wine in order to strengthen and preserve it, he did not hesitate to add large quantities of sugar to the must, so much that the juice would not ferment to dryness. The horticultural and architectural writer Andrew Jackson Downing, a good judge, remembered Adlum's wine as "only tolerable";[70] Nicholas Longworth, who may be said to have succeeded to Adlum's work with Catawba, agreed that Adlum's wine was poor, not only for its artificial sweetness but because, he reported, Adlum was not above eking out his superior juice in lean years with the juice from the wild grapes growing in the woods that surrounded his vineyard.[71] This practice Longworth politely attributed to Adlum's "poverty" (whatever the size of Adlum's fortune when he retired in 1798, it does not seem to have been adequate to carry him easily to the end in 1836). After all these qualifications and reservations have been made, the main point remains: Adlum had found a grape from which good wine might be made; he had been quick to recognize the fact; and he had been able to publicize it effectively. At the time, and given the circumstances, he had done precisely what the long struggle to create an American winegrowing industry needed.

By some providence, the introduction of Adlum's Catawba wine coincided with the publication of Adlum's book on grape growing and winemaking: his Memoir on the Cultivation of the Fine in America, and the Best Mode of Making Wine , published in Washington early in 1823,[72] appeared almost together with the first distribution of Catawba. Perhaps he planned it that way. In any event, the two strokes, the new book and the new wine together, have made Adlum's mark on the record of American winegrowing permanent and visible to a degree hardly matched by any other individual's. His book is interesting, and original to the extent that it chronicles his own experience with vine growing and winemaking, going back to his residence at Havre de Grace at the end of the eighteenth century. As a treatise on viticulture, it is derivative; Adlum did not pretend otherwise, and freely acknowledged the fact that he was following the lines laid down by established European writers. He thus has little or nothing to say on such crucial subjects as the diseases that had to be faced by any American viticulturist. He spends more time on winemaking, but here, too, his achievement is not remarkable. His disposition to use too much sugar in his wine has already been noticed. Moreover, he recommended such practices as fermentation at high temperatures—up to 115° Fahrenheit!—which would horrify winemakers today.[73] But one may make many allowances for Adlum. He wrote with as much independence as could be expected in his circumstances, he clearly understood the importance of native vines, he

firmly opposed the bad practice of drowning wines in brandy, and, in company with all of his notable predecessors, he acted with a conscious sense of patriotic selflessness: "a desire to be useful to my countrymen, has animated all my efforts," he declared in the preface to his Memoir . As he wrote to Nicholas Longworth not long after the triumphant introduction of the Catawba, "in introducing this grape to public notice, I have done my country a greater service than I should have done, had I paid the national debt."[74] And his confidence was infectious. James Madison, in sending two copies of Adlum's book to the Agricultural Society of Albemarle, wrote that now "nothing seems wanting to the addition of the grape to our valuable productions, but decisive efforts."[75]

For the next half-dozen years after he had brought Catawba wine to the public for the first time, Adlum was the recognized oracle on the subject of wines and vines in America. He wrote frequently to the agricultural press—a significantly larger and more influential part of the national press in those rural days than now—describing his practices and setting forth his prescriptions for others. He circularized the great men of the day to attract their attention to the cause of wine-growing, usually sending a bottle of his produce to help make the point; he lobbied the agricultural societies to get them to recognize viticulture and winemaking as activities worthy of official encouragement; he tried to get the federal government to establish a national vineyard in the District of Columbia in which the many varieties of native vines might be planted "to ascertain their growth, soil, and produce, and to exhibit to the Nation, a new source of wealth, which had been too long neglected."[76] Since the intensity of his enthusiasm far exceeded that of the institutions to which he appealed, he did not get very far immediately. But probably much of what we now have is owed to the example he set.

Certainly Adlum's activities had something to do with the noticeable growth of interest in winegrowing that spread over the United States in the 1820s. Adlum himself published exciting figures on the profits to be made from small vineyards, such as almost every American might reasonably plant. In 1824 he notified the public that the demand for cuttings from his vineyard was already growing beyond his ability to supply.[77] In 1825 he was able to boast that he had aroused national interest: "I have correspondents from Maine to East Florida, on the sea-board, and in the states of Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee, to the north and west, on the subject of planting vineyards and making wine."[78] It was in this year, probably, that the wealthy Ohio lawyer and landowner Nicholas Longworth visited Adlum and obtained from him cuttings of the Catawba vine:[79] the results of that encounter form part of another chapter. In 1827 Adlum had the dubious pleasure of inspiring a new contribution to the literature of American winegrowing. The work was a treatise in verse called The Vigneron , published in Washington, D.C., by one Isaac G. Hutton.[80] This strange performance, touching on temperance, soils, planting, cultivation, and other subjects, prints an essay by Adlum "On Propagating Grape Vines in a Vineyard" as an appendix, and also makes such familiar allusion to Adlum as to show that, if he did not beget the poem, he must at least have known that it was being perpetrated.[81]

All over the country waves were felt and echoes heard from the stir that Adlum had made. From South Carolina to New York, farmers, nurserymen, and journalists paid a new attention to the grape, not wholly because of Adlum, but in large part because of the fact that he had done well with a native grape at last and was equipped to publicize what he had done. In Maryland, for example, Adlum had been particularly aggressive in advertising his work, but met a disappointing reluctance on the part of the state agricultural society to do anything about viticulture.[82] Then, in 1828, a company of private gentlemen received a charter from the state to form the "Maryland Society for Promoting the Culture of the Vine," capitalized at $3,000, and furnished with many respectable names among its officers.[83] The intention of the society was to show the way towards scientific advance in vine growing and winemaking. Its plan, evidently inspired by Adlum's notion of a national vineyard, was to establish a small vineyard in which trials could be made of both European and native grapes, and, by its example, encourage the formation of other such societies. After a good deal of early publicity, however, not much seems to have been done. The society still had not managed to find land for a vineyard a year after its founding, and hence could do nothing towards hiring apprentices, selling cuttings, holding exhibitions, and diffusing information as it proposed to do. Perhaps the most interesting thing about the society is the fact that, even though it was called forth by Adlum's success with the Catawba, it still proposed to experiment with vinifera; it marked, as Hedrick has noted, the last organized effort to grow European grapes in eastern America—or rather, the last before the renewed trials of the late twentieth century.[84] Of course, the untried assumption that vinifera would grow here continued to be widespread among individuals. S. I. Fisher, for example, in his Observations on the Character and Culture of the European Vine (Philadelphia, 1834), argued that if we would only imitate the vine growing practices of the Swiss, we would succeed in acclimating the foreign vine. Fisher recommends, too, that Legaux's old Pennsylvania Vine Company should be revived for the purpose.

In 1826 Adlum published another treatise—a pamphlet, really—under the title of Adlum on Making Wine ,[85] but his importance now was less as a winemaker than as a nurseryman promoting the wide distribution of native grapes in a country now at last prepared to believe in them. Adlum used a part of his Memoir as a catalog of his nursery, offering cuttings for sale: the list of the varieties he had available is an instructive record of the state of varietal development then. He includes a number of vinifera grapes, but the heart of the list lay in the native vines: "Tokay" (as he then called the Catawba), Schuylkill Muscadel (Alexander), Bland's Madeira, Clifton's Constantia (a variant of the Alexander), Muncy (later affirmed to be Catawba), Worthington, Red Juice, Carolina Purple Muscadine, and Orwigsburgh. The Red Juice grape is presumably that which the Harmonists are reported to have grown along with the Alexander; the Worthington is probably the variety better known as Clinton, a hybrid of riparia, labrusca, and some vinifera; it was later much used for red wine, but without giving much satisfaction—the fruit, Hedrick says, is "small and sour," the wine "too raucous."[86] Bland's Madeira is a labrusca-

vinifera hybrid like the Alexander, and of almost as early discovery as the Alexander. Colonel Theodorick Bland, of Virginia, brought it to notice just before the Revolution, and there are reports of it under various names—Powel or Powell is the most common—in vineyards in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere in the early nineteenth century. Bland's Madeira was probably the "Madeira" that Dufour obtained from Legaux and grew in Kentucky and Indiana, but we cannot be sure.

In 1828 Adlum brought out a second edition of the Memoir , in which the list has been increased by the addition of four more grapes: an unnamed variety from North Carolina, two labruscas called Luffborough and Elkton, and Isabella. The last is a superior chance hybrid of vinifera and labrusca, introduced and promoted by the Long Island nurseryman and viticulturist William Prince as early as 1816. Originating, probably, in South Carolina, it was the chief alternative to Catawba for many years, for it ripens earlier than Catawba and is therefore preferred by growers in the middle Atlantic and New England states. Had Prince made wine in commercial quantities from the Isabella and publicized it, he might well have challenged Adlum for the position as the first to sponsor a good native grape. Adlum's list is a reasonably complete enumeration of what an American winegrower had to work with at the end of the first quarter of the nineteenth century. All of these varieties were accidents, the result of spontaneous seedlings; both the Isabella and the Catawba, the best two of the lot, have serious cultural defects and are susceptible to diseases that could not then be controlled; none was fit for the production of red wine, a severe limitation if one agrees that it is the first duty of a wine to be red. It was not, in short, much of a basis to work on, but it was all that was available up to the decade before the Civil War. Then there was a great and sudden increase in the number of varieties available, thanks to a belated but enthusiastic outburst of interest in grape breeding.

One of the last episodes in Adlum's career as a propagandist of winegrowing was his petition addressed to the U.S. Senate in April 1828 stating his claim to recognition for his work as a vineyardist and winemaker and requesting that the Senate take steps to make the newly published second edition of his Memoir "useful to the United States, and of some advantage to your petitioner ."[87] The Senate committee on agriculture, to which the petition was referred, proposed that the Treasury buy 3,000 copies of Adlum's book for distribution by members of the Senate, but the proposal struck the senators as unorthodox and was defeated.[88] It seems reasonable to suppose that Adlum needed the money; Longworth, as we have already seen, noted Adlum's "poverty," and there is further evidence of his neediness in 1831, when Adlum laid claim to a tiny pension for which he was eligible as a soldier in the Revolution.[89] From 1830 until his death in 1836 he does not figure in the public discussion of grapes and wine, though that went on in full flow. Adlum's name fell into obscurity after his death; his modest home in Georgetown stood until, derelict, it was demolished early in this century; the knowledge of his burial place was, for a long time, lost; and the record of his work was forgotten

until brought back to light by the researches of the great botanical scholar and writer Liberty Hyde Bailey at the end of the nineteenth century.

As with most "Fathers" of institutions or of complex inventions, like the airplane or the automobile, Adlum can hardly be claimed to have been sole father to American viticulture. His establishment was at no time anything but a very small affair; he was not the first to introduce a usable hybrid native grape; he was certainly not the first to produce a tolerable wine; nor was his Memoir the first American treatise on the subject. It would be more sensible to say that he came at the right time in the right place, and that he is fully entitled to the credit of introducing the Catawba and of knowing how to promote it. After Adlum, the history of wine in eastern America is a different story.