Peter Legaux and the Pennsylvania Vine Company

The first notable postrevolutionary attempt to establish a successful viticulture was carried out near Philadelphia, where Penn had planted his vines a hundred years before. In 1786 a Frenchman of an adventurous, but rather dubious, past named Peter Legaux (1748-1827) bought an estate of 206 acres at Spring Mill, on

26

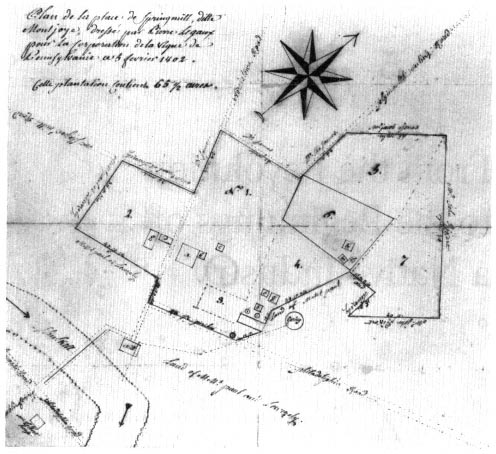

"Plan de la place de Springmill, ditte Montjoye, dressé par Pierre Legaux pour La Corporation de

la Vigne de Pennsylvania le 5 fevrier 1802" ("Plan of the site of Springmill, called Mountjoy, prepared

by Pierre Legaux for the Pennsylvania Vine Company, 5 February 1802"). This plan of Legaux's

vineyards was made immediately after the Pennsylvania Vine Company had at last succeeded in

achieving legal incorporation—nine years after the project had been begun—and no doubt expresses

the renewed hopes to which the event gave rise. They were doomed to disappointment.

(Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

the east bank of the Schuylkill, two miles below Conshohocken in Montgomery' County;[1] there he began planting European vines on the slopes of his property and building vaults for wine storage. Legaux's farm has been described for us in unusual detail at an early stage of its development by the French publicist and politician Jacques Pierre Brissot de Warville, who devoted several pages of his New Travels in the United States of America (1788) to Legaux as a bright instance of what Frenchmen might hope to achieve in America. Brissot found Legaux in a well-built, solid stone house, enjoying a superb view, and surrounded by all the emblems of plenty: six servants, horses and cattle, fields of grain and meadows of grass, beehives

and gardens, and a new vineyard, standing on a southeastern slope and planted with vines from the Médoc.[2] Despite this idyllic presentation, not all was smooth going for Legaux. He lived without his family, who had remained in France; he did not know English well; his servants were often lazy and unruly; and there were quarrels with his neighbors, even though they were all peaceable Quakers.[3]

Legaux, who began life as a lawyer in Metz, was in fact a remarkably difficult and litigious neighbor. When another and later French traveller, the duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, was directed to Legaux's vineyard as one of the sights of the Philadelphia region in 1795, he took an instant dislike to Legaux—a man, he wrote, whose "whole physiognomy indicates cunning rather than goodness of heart." The duc was scandalized to learn that Legaux, in the nine years of his residence in Pennsylvania, had engaged in two hundred lawsuits, all of them unsuccessful![4] Despite this, or in part because of it, Legaux was widely known and well thought of in Pennsylvania. He seems, in fact, to have had a genius for self-promotion. In 1789, only two years after he set out his first vines, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society, a badge of unquestioned acceptance in the City of Brotherly Love. As so many others before it had done, the experiment that he was making in vine growing at once aroused hopeful curiosity, and, no doubt, as much or more amused skepticism. It was, at any rate, the object of much attention. When, for example, the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in 1792, Washington and other notables journeyed the thirteen miles from town to see the promising new vineyard.[5] There was even an absurd rumor that the republican French, alerted by the favorable description given by Brissot, and anxious as always for the security of their wine trade, had secretly instructed their American minister to pay Legaux to pull up his vines.[6]

After he had had some experience with growing vines and had learned how hard it is to keep an experiment going without financial backing, Legaux decided to obtain public support. To do this he secured an act of the legislature forming a "company for the purpose of promoting the cultivation of vines," usually called the Pennsylvania Vine Company. The enabling legislation was passed in March 1793, when commissioners were appointed to receive subscriptions for the company's stock of 1,000 shares at $20 each.[7] Despite the respectable auspices of the enterprise, money came in slowly. Only 139 shares were sold in a year, and Legaux soon found himself in difficulties. He wrote to General Washington offering to sell his house as a country residence for the president during congressional sessions (then still held in Philadelphia) on condition that he be allowed to continue his "improvements in the cultivation of the vine"—a work that would be lost were Legaux to be, as he feared, sold up for debt.[8] Though his property was, nominally at least, seized in execution of a writ of sale in 1792, by one means or another Legaux yet managed to hang on to it. On 16 August 1793 the Philadelphia Daily Advertiser proclaimed that

the first vintage ever held in America would begin at the vineyard, near Spring Mill, and in a few weeks Mr. Legaux will begin to produce American wine, made upon prin-

ciples hitherto unknown, or at least unpracticed here. This will form a new era in the history of American agriculture. . . . succeeding generations will bless the memory of the man who first taught the Americans the culture of this generous plant.[9]

The style of the notice tells us something about Legaux's promotional talents—"the first vintage ever held in America" was a fairly audacious claim to be making three hundred years after Columbus. It tells us something, too, about the reasons for his unpopularity with his neighbors, who were probably a bit sour at the thought of blessing Legaux's memory. The vintage yielded, so we learn from a later document, six barrels of wine plus a small quantity of "Tokay"; all were "preserved in perfection without the addition of another [sic ] single drop of alcohol."[10]

Such publicity did little to relieve Legaux's money troubles. In 1794 he petitioned the U.S. Senate for support of his vineyard, without success.[11] An English traveller visiting Legaux that year was much disappointed by what he saw: the vineyard, he wrote, "does not succeed at all." When La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt called the next year, he found Legaux in desperate straits. Because Legaux could not meet the payments, his farm had been sold and he was reduced to living on fifteen rented acres, including the deteriorating house and the vineyard. There, wearing "stockings full of holes and a dirty night-cap," Legaux lived in penury, hiding from suspicious visitors, but still persisting in the care of his vines.[12] And by one means or another he clung to the Spring Mill estate. Whatever one might think of Legaux's behavior as a neighbor and of his unabashedness as a promoter, it is only fair to admit that his determination to succeed at winegrowing was deep and genuine.

Early in 1800 the Pennsylvania legislature passed an act to stimulate the lagging sale of Vine Company stock by making the terms of purchase easier. Thereupon an elegant prospectus—not signed, but doubtless written by Legaux—was put before the public. In this document the history of the vineyard since planting began at Spring Mill in 1787 is recapitulated.[13] Legaux is said to have begun with 300 plants from Burgundy, Champagne, and Bordeaux. Then follows an assertion that later, as we shall see, became the focus of a controversy not yet fully decided. After the first plants were obtained, the prospectus says, Legaux then "procured plants of the Constantia vine from the Cape of Good Hope." This was the vine for which, so Legaux told La Rochefoucauld in 1795, he had paid the remarkable sum of forty guineas,[14] and of which he did considerable advertising. It was not, however, the Constantia grape at all, or anything like it, being in fact the native hybrid best known as the Alexander. Legaux never gave up his insistence that the grape was what he said it was. Since he sold large quantities of it at premium prices under its attractive foreign name, the question has naturally arisen: Was he lying? Or was he honestly deceived? There is presumptive evidence both ways, but not of a kind to settle the matter.

Whatever the truth, the rest of the prospectus is straightforward. It declares that Legaux now had 18,000 vines set out in his vineyard and a nursery of several

27

Entry for 15 April 1805 in Peter Legaux's journal, recording the receipt of vines from France

for planting in the vineyards of the Pennsylvania Vine Company. The entry reads: "This

day at ½ pass 10, o'clock at Night, I received a letter from Mr. McMahon with 3 Boxes of

Grapevines, sended by Mr. Lee Consul Americain from Bordeaux, all in very good order

and good plantes of Chateaux Margeaux, Lafitte, and haut Brion. 4500 plantes for 230

# . . . and order to send in Town for more etc." (American Philosophical Society)

hundred thousand more, all ready to help produce the long-desired American wine. The scope of the company's proposed activity is set forth in detail, its main purposes being "the cultivation of the vine and the supply of wines, brandy, tartar and vinegar from the American soil, and the extension of vineyards and nurseries of plants of the Burgundy, Champagne, Bordeaux and Tokay wines, and to procure vine-dressers for America."[15] The last object was to be achieved by accepting apprentices at Legaux's vineyard for terms of three to five years, on conditions varying with the size of a shareholder's interest.

Legaux left no opportunity untried. He wrote to Jefferson in March 1801, just after Jefferson's first inauguration, to congratulate him on his election and offering to send him some thousands of vines from Legaux's nursery so that they might be tried in Virginia. When Jefferson politely declined, Legaux responded more boldly, sending him an account of his struggles to found the company and inviting the president to join the subscribers. His enemies were many, Legaux wrote in his charmingly Frenchified English, and especially "the medium classe of the people opposed more phase of this improvement than the richer."[16] Jefferson was either too cautious or too busy or both, for Legaux did not manage to add the dignity of the presidential name to his subscription list. He did, however, send vines to Jefferson the next year, and these were planted at Monticello by one of the Italian vine dressers brought over years before by Philip Mazzei.[17]

At last, in January 1802, the required minimum number of subscriptions to establish the Pennsylvania Vine Company was obtained, the company's incorporation was officially sealed, and Legaux was made superintendent of the company's vineyard at a good salary.[18] It had taken him nearly ten years to reach this official starting point, yet the names of his shareholders make a roster of the federal aristocracy—Citizen Genet, Stephen Girard, Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and Benjamin Rush, to name a few, were all investors in the Pennsylvania Vine Company.[19] Legaux was right when he told Jefferson that the "richer" rather than the "medium" class were his main support. It is comforting to think that these were, all of them, men of substance already, for they never made a penny from their investment in the Vine Company. The struggle to maintain the company's finances was

28

William Lee (1772-1840), in uniform as American consul at

Bordeaux. Lee had a hand in two notable, if unsuccessful,

winegrowing enterprises in the early Republic. He sent

vines from the great châteaux of Bordeaux to Legaux's

Pennsylvania Vineyard Company in 1805; and in 1816 he

was instrumental in forming the plans for the Alabama

Vine and Olive Company. He also projected a book

on winegrowing in the 1820s but did not publish it. (From

Mary Lee Mann, ed., A Yankee Jeffersonian [1958])

always uphill, and the enthusiasm of the stockholders grew feebler as the struggle grew harder.

We can learn something about that struggle in detail because the journal that Legaux kept as a record of the Vine Company's work from 1803 onwards has survived in part.[20] It tells a story of such wasted labor and frustration that one wonders at the strength of Legaux's persistence—he seems never to have acknowledged to himself that the odds against him were hopeless. The record for the year 1803 will do as a representative instance. In the spring Legaux planted 14,000 vinifera vines at Spring Mill, or Montjoy, as his estate was called. The finances of the company were then relatively vigorous, after the recent completion of the incorporation proceedings, and Legaux was able to hire regular help for the company's vineyards, of which there appear to have been two, and for his own vineyard, which he maintained separately from the company enterprise. Some of the hands were of English stock—Joseph Nobbett and Abel Pond, for example; others were French, such as André Dupalais and Eustache Pailliase. From time to time the journal records the visits to Spring Mill of the managers and stockholders of the company, often accompanied by their wives and daughters, or by distinguished visitors come to see the interesting sight of a commercial American vineyard. But they saw no very cheerful sight in 1803. Heavy frosts in May and a severe hail storm in June blasted the new plantings, and by the end of the season only 582 vines out of 14,000 still grimly survived: "I am unable to make wine this year," Legaux sadly concluded,[21] and that failure made the end almost certain. The next year Legaux managed to make a few bottles of wine from his own vineyard, but the society's property was

in bad shape "by want of supply and money."[22] A fresh start was made in 1805; William Lee, the American consul in Bordeaux, sent 4,500 cuttings from Chateau Margaux, Chateau Lafite, and Chateau Haut-Brion to guarantee the most aristocratic of all pedigrees to Legaux's republican vineyard.[23] These noble vines were supplemented by another 1,500 from Malaga. All shared a common fate. The heat and drought of the summer afflicted them, and though enough survived to be shown to the governor of Pennsylvania when he paid a visit the next year, Legaux was compelled to write in 1807 that all were neglected and overrun.[24]

The company had been authorized to conduct a lottery to raise funds in 1806, but the plan did not work out, and another lottery in 1811 also failed.[25] By this time the company seemed dead: such labor as was performed was performed by Legaux himself, who confided to his journal that in his lonely and unrewarding work "Nobody is my faithful Companion!!!"[26] Nevertheless, Legaux kept something going. He came to a definite—and correct—conclusion in 1809 when he observed that, of all his grapes, only the one that he called the Cape managed to grow: "all other sorte may be abandoned," he wrote then, and a year later he advised his journal that, in order to redeem the company's purposes, "the best will be to pull out all the plants, and planted again with the Cape of Good Hope."[27]

If Legaux's advice—dearly earned advice it was—had been acted on, the company might have succeeded in making wine, as Dufour was already doing from the Cape grape in Indiana, originally obtained from Legaux's own vineyard.[28] But protracted failures had destroyed Legaux's credit with the managers of the company. He had, indeed, made a first vintage from the company's vineyard with Cape grapes in September 1809,[29] but it was both too little and too late. The secretary of the company was a man who had notions of his own about how things should be done. He was Bernard McMahon, an Irishman who settled in Philadelphia as a nurseryman and seedsman and became the city's oracle on horticulture. His American Gardener's Calendar (1806) was the first thorough guide to the subject published in this country and remained a standard for half a century. McMahon, who took a special interest in the viticultural work of the company, now decided that a change was required. A new superintendent was appointed to oversee the company's vineyard in place of Legaux, but after a year Legaux had the bitter satisfaction of reporting that the man had bungled the job, the vines being pruned so badly that they would produce no grapes at all that season.[30] The dispirited stockholders were now ready to relinquish the entire thing back into Legaux's hands, while retaining title to the land and requiring that Legaux continue to keep up the vineyards. This Legaux was eager to do, but his eagerness had no reward. In the year after his restoration, the vines were devastated by a plague of caterpillars, and at the end of 1813 Legaux made this desolate entry in his journal: "No horses nobody no money and any assistance whatever to expect; what I shall do??"[31]

It is perhaps just as well that the journal for 1814-22 is missing; it could only repeat the tale of hapless vicissitude already clear enough. When the journal resumes in 1822 we hear no more of winegrowing. Legaux is old and ill, more inter-

ested in recording the details of the weather (a lifelong obsession with him) and in collecting information on the diseases that went round the neighborhood than in the state of his vines and the hope for a good American wine. His property at Spring Mill, though it had several times been put up for sale by the sheriff for debt, had at last been rescued by Legaux's son-in-law,[32] and there, in 1827, Legaux died, his dream of the Vineyard Company long since vanished. The forty years of vine growing at Spring Mill seemed to have led to nothing.