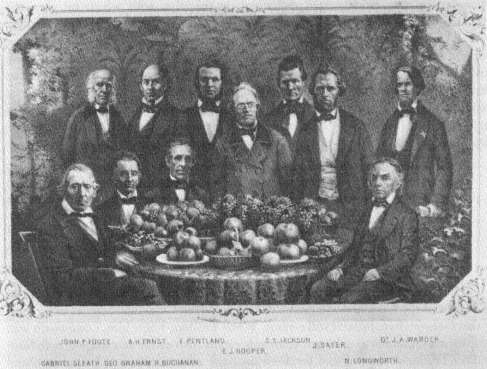

PART 2

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AN INDUSTRY

5

From the Revolution to the Beginnings of a Native Industry

A After independence much of the winegrowing in this country in many ways resembled what had been done before the Revolution: companies for developing vineyards were founded, as they had been earlier in Virginia in the seventies; communities of foreign viticulturists were subsidized, as they had been before in the Carolinas and elsewhere; religious communities tried to make winegrowing a part of their economy, as they had tried before in Pennsylvania and New England. In general, the typical American winegrower was likely to be a German or a Frenchman, as he had been before the Revolution. Yet the long-sought success was at last a native affair, brought about by a Pennsylvanian growing a North Carolinian grape in, with symbolic fitness, the nation's new capital, Washington, D.C.

Peter Legaux and the Pennsylvania Vine Company

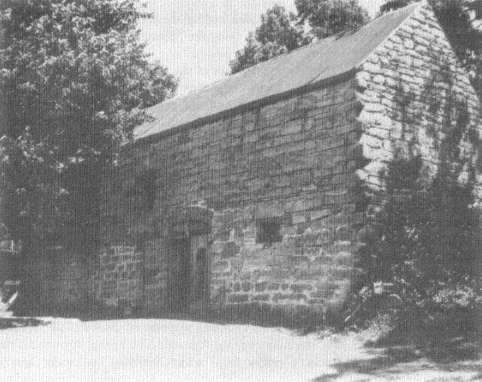

The first notable postrevolutionary attempt to establish a successful viticulture was carried out near Philadelphia, where Penn had planted his vines a hundred years before. In 1786 a Frenchman of an adventurous, but rather dubious, past named Peter Legaux (1748-1827) bought an estate of 206 acres at Spring Mill, on

26

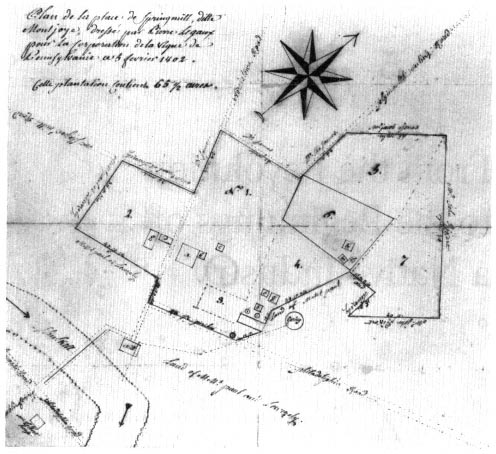

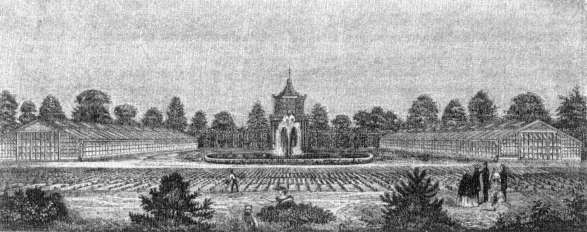

"Plan de la place de Springmill, ditte Montjoye, dressé par Pierre Legaux pour La Corporation de

la Vigne de Pennsylvania le 5 fevrier 1802" ("Plan of the site of Springmill, called Mountjoy, prepared

by Pierre Legaux for the Pennsylvania Vine Company, 5 February 1802"). This plan of Legaux's

vineyards was made immediately after the Pennsylvania Vine Company had at last succeeded in

achieving legal incorporation—nine years after the project had been begun—and no doubt expresses

the renewed hopes to which the event gave rise. They were doomed to disappointment.

(Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

the east bank of the Schuylkill, two miles below Conshohocken in Montgomery' County;[1] there he began planting European vines on the slopes of his property and building vaults for wine storage. Legaux's farm has been described for us in unusual detail at an early stage of its development by the French publicist and politician Jacques Pierre Brissot de Warville, who devoted several pages of his New Travels in the United States of America (1788) to Legaux as a bright instance of what Frenchmen might hope to achieve in America. Brissot found Legaux in a well-built, solid stone house, enjoying a superb view, and surrounded by all the emblems of plenty: six servants, horses and cattle, fields of grain and meadows of grass, beehives

and gardens, and a new vineyard, standing on a southeastern slope and planted with vines from the Médoc.[2] Despite this idyllic presentation, not all was smooth going for Legaux. He lived without his family, who had remained in France; he did not know English well; his servants were often lazy and unruly; and there were quarrels with his neighbors, even though they were all peaceable Quakers.[3]

Legaux, who began life as a lawyer in Metz, was in fact a remarkably difficult and litigious neighbor. When another and later French traveller, the duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, was directed to Legaux's vineyard as one of the sights of the Philadelphia region in 1795, he took an instant dislike to Legaux—a man, he wrote, whose "whole physiognomy indicates cunning rather than goodness of heart." The duc was scandalized to learn that Legaux, in the nine years of his residence in Pennsylvania, had engaged in two hundred lawsuits, all of them unsuccessful![4] Despite this, or in part because of it, Legaux was widely known and well thought of in Pennsylvania. He seems, in fact, to have had a genius for self-promotion. In 1789, only two years after he set out his first vines, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society, a badge of unquestioned acceptance in the City of Brotherly Love. As so many others before it had done, the experiment that he was making in vine growing at once aroused hopeful curiosity, and, no doubt, as much or more amused skepticism. It was, at any rate, the object of much attention. When, for example, the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia in 1792, Washington and other notables journeyed the thirteen miles from town to see the promising new vineyard.[5] There was even an absurd rumor that the republican French, alerted by the favorable description given by Brissot, and anxious as always for the security of their wine trade, had secretly instructed their American minister to pay Legaux to pull up his vines.[6]

After he had had some experience with growing vines and had learned how hard it is to keep an experiment going without financial backing, Legaux decided to obtain public support. To do this he secured an act of the legislature forming a "company for the purpose of promoting the cultivation of vines," usually called the Pennsylvania Vine Company. The enabling legislation was passed in March 1793, when commissioners were appointed to receive subscriptions for the company's stock of 1,000 shares at $20 each.[7] Despite the respectable auspices of the enterprise, money came in slowly. Only 139 shares were sold in a year, and Legaux soon found himself in difficulties. He wrote to General Washington offering to sell his house as a country residence for the president during congressional sessions (then still held in Philadelphia) on condition that he be allowed to continue his "improvements in the cultivation of the vine"—a work that would be lost were Legaux to be, as he feared, sold up for debt.[8] Though his property was, nominally at least, seized in execution of a writ of sale in 1792, by one means or another Legaux yet managed to hang on to it. On 16 August 1793 the Philadelphia Daily Advertiser proclaimed that

the first vintage ever held in America would begin at the vineyard, near Spring Mill, and in a few weeks Mr. Legaux will begin to produce American wine, made upon prin-

ciples hitherto unknown, or at least unpracticed here. This will form a new era in the history of American agriculture. . . . succeeding generations will bless the memory of the man who first taught the Americans the culture of this generous plant.[9]

The style of the notice tells us something about Legaux's promotional talents—"the first vintage ever held in America" was a fairly audacious claim to be making three hundred years after Columbus. It tells us something, too, about the reasons for his unpopularity with his neighbors, who were probably a bit sour at the thought of blessing Legaux's memory. The vintage yielded, so we learn from a later document, six barrels of wine plus a small quantity of "Tokay"; all were "preserved in perfection without the addition of another [sic ] single drop of alcohol."[10]

Such publicity did little to relieve Legaux's money troubles. In 1794 he petitioned the U.S. Senate for support of his vineyard, without success.[11] An English traveller visiting Legaux that year was much disappointed by what he saw: the vineyard, he wrote, "does not succeed at all." When La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt called the next year, he found Legaux in desperate straits. Because Legaux could not meet the payments, his farm had been sold and he was reduced to living on fifteen rented acres, including the deteriorating house and the vineyard. There, wearing "stockings full of holes and a dirty night-cap," Legaux lived in penury, hiding from suspicious visitors, but still persisting in the care of his vines.[12] And by one means or another he clung to the Spring Mill estate. Whatever one might think of Legaux's behavior as a neighbor and of his unabashedness as a promoter, it is only fair to admit that his determination to succeed at winegrowing was deep and genuine.

Early in 1800 the Pennsylvania legislature passed an act to stimulate the lagging sale of Vine Company stock by making the terms of purchase easier. Thereupon an elegant prospectus—not signed, but doubtless written by Legaux—was put before the public. In this document the history of the vineyard since planting began at Spring Mill in 1787 is recapitulated.[13] Legaux is said to have begun with 300 plants from Burgundy, Champagne, and Bordeaux. Then follows an assertion that later, as we shall see, became the focus of a controversy not yet fully decided. After the first plants were obtained, the prospectus says, Legaux then "procured plants of the Constantia vine from the Cape of Good Hope." This was the vine for which, so Legaux told La Rochefoucauld in 1795, he had paid the remarkable sum of forty guineas,[14] and of which he did considerable advertising. It was not, however, the Constantia grape at all, or anything like it, being in fact the native hybrid best known as the Alexander. Legaux never gave up his insistence that the grape was what he said it was. Since he sold large quantities of it at premium prices under its attractive foreign name, the question has naturally arisen: Was he lying? Or was he honestly deceived? There is presumptive evidence both ways, but not of a kind to settle the matter.

Whatever the truth, the rest of the prospectus is straightforward. It declares that Legaux now had 18,000 vines set out in his vineyard and a nursery of several

27

Entry for 15 April 1805 in Peter Legaux's journal, recording the receipt of vines from France

for planting in the vineyards of the Pennsylvania Vine Company. The entry reads: "This

day at ½ pass 10, o'clock at Night, I received a letter from Mr. McMahon with 3 Boxes of

Grapevines, sended by Mr. Lee Consul Americain from Bordeaux, all in very good order

and good plantes of Chateaux Margeaux, Lafitte, and haut Brion. 4500 plantes for 230

# . . . and order to send in Town for more etc." (American Philosophical Society)

hundred thousand more, all ready to help produce the long-desired American wine. The scope of the company's proposed activity is set forth in detail, its main purposes being "the cultivation of the vine and the supply of wines, brandy, tartar and vinegar from the American soil, and the extension of vineyards and nurseries of plants of the Burgundy, Champagne, Bordeaux and Tokay wines, and to procure vine-dressers for America."[15] The last object was to be achieved by accepting apprentices at Legaux's vineyard for terms of three to five years, on conditions varying with the size of a shareholder's interest.

Legaux left no opportunity untried. He wrote to Jefferson in March 1801, just after Jefferson's first inauguration, to congratulate him on his election and offering to send him some thousands of vines from Legaux's nursery so that they might be tried in Virginia. When Jefferson politely declined, Legaux responded more boldly, sending him an account of his struggles to found the company and inviting the president to join the subscribers. His enemies were many, Legaux wrote in his charmingly Frenchified English, and especially "the medium classe of the people opposed more phase of this improvement than the richer."[16] Jefferson was either too cautious or too busy or both, for Legaux did not manage to add the dignity of the presidential name to his subscription list. He did, however, send vines to Jefferson the next year, and these were planted at Monticello by one of the Italian vine dressers brought over years before by Philip Mazzei.[17]

At last, in January 1802, the required minimum number of subscriptions to establish the Pennsylvania Vine Company was obtained, the company's incorporation was officially sealed, and Legaux was made superintendent of the company's vineyard at a good salary.[18] It had taken him nearly ten years to reach this official starting point, yet the names of his shareholders make a roster of the federal aristocracy—Citizen Genet, Stephen Girard, Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and Benjamin Rush, to name a few, were all investors in the Pennsylvania Vine Company.[19] Legaux was right when he told Jefferson that the "richer" rather than the "medium" class were his main support. It is comforting to think that these were, all of them, men of substance already, for they never made a penny from their investment in the Vine Company. The struggle to maintain the company's finances was

28

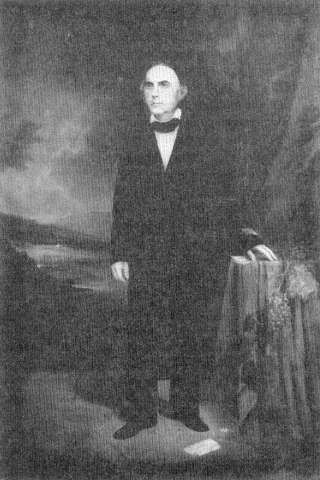

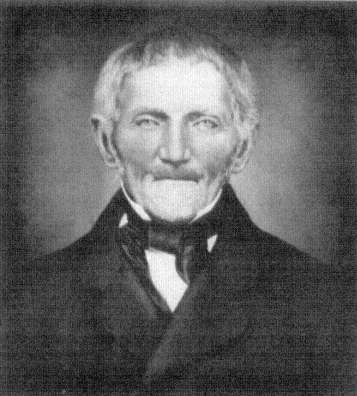

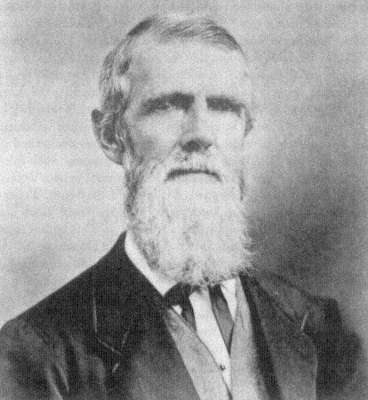

William Lee (1772-1840), in uniform as American consul at

Bordeaux. Lee had a hand in two notable, if unsuccessful,

winegrowing enterprises in the early Republic. He sent

vines from the great châteaux of Bordeaux to Legaux's

Pennsylvania Vineyard Company in 1805; and in 1816 he

was instrumental in forming the plans for the Alabama

Vine and Olive Company. He also projected a book

on winegrowing in the 1820s but did not publish it. (From

Mary Lee Mann, ed., A Yankee Jeffersonian [1958])

always uphill, and the enthusiasm of the stockholders grew feebler as the struggle grew harder.

We can learn something about that struggle in detail because the journal that Legaux kept as a record of the Vine Company's work from 1803 onwards has survived in part.[20] It tells a story of such wasted labor and frustration that one wonders at the strength of Legaux's persistence—he seems never to have acknowledged to himself that the odds against him were hopeless. The record for the year 1803 will do as a representative instance. In the spring Legaux planted 14,000 vinifera vines at Spring Mill, or Montjoy, as his estate was called. The finances of the company were then relatively vigorous, after the recent completion of the incorporation proceedings, and Legaux was able to hire regular help for the company's vineyards, of which there appear to have been two, and for his own vineyard, which he maintained separately from the company enterprise. Some of the hands were of English stock—Joseph Nobbett and Abel Pond, for example; others were French, such as André Dupalais and Eustache Pailliase. From time to time the journal records the visits to Spring Mill of the managers and stockholders of the company, often accompanied by their wives and daughters, or by distinguished visitors come to see the interesting sight of a commercial American vineyard. But they saw no very cheerful sight in 1803. Heavy frosts in May and a severe hail storm in June blasted the new plantings, and by the end of the season only 582 vines out of 14,000 still grimly survived: "I am unable to make wine this year," Legaux sadly concluded,[21] and that failure made the end almost certain. The next year Legaux managed to make a few bottles of wine from his own vineyard, but the society's property was

in bad shape "by want of supply and money."[22] A fresh start was made in 1805; William Lee, the American consul in Bordeaux, sent 4,500 cuttings from Chateau Margaux, Chateau Lafite, and Chateau Haut-Brion to guarantee the most aristocratic of all pedigrees to Legaux's republican vineyard.[23] These noble vines were supplemented by another 1,500 from Malaga. All shared a common fate. The heat and drought of the summer afflicted them, and though enough survived to be shown to the governor of Pennsylvania when he paid a visit the next year, Legaux was compelled to write in 1807 that all were neglected and overrun.[24]

The company had been authorized to conduct a lottery to raise funds in 1806, but the plan did not work out, and another lottery in 1811 also failed.[25] By this time the company seemed dead: such labor as was performed was performed by Legaux himself, who confided to his journal that in his lonely and unrewarding work "Nobody is my faithful Companion!!!"[26] Nevertheless, Legaux kept something going. He came to a definite—and correct—conclusion in 1809 when he observed that, of all his grapes, only the one that he called the Cape managed to grow: "all other sorte may be abandoned," he wrote then, and a year later he advised his journal that, in order to redeem the company's purposes, "the best will be to pull out all the plants, and planted again with the Cape of Good Hope."[27]

If Legaux's advice—dearly earned advice it was—had been acted on, the company might have succeeded in making wine, as Dufour was already doing from the Cape grape in Indiana, originally obtained from Legaux's own vineyard.[28] But protracted failures had destroyed Legaux's credit with the managers of the company. He had, indeed, made a first vintage from the company's vineyard with Cape grapes in September 1809,[29] but it was both too little and too late. The secretary of the company was a man who had notions of his own about how things should be done. He was Bernard McMahon, an Irishman who settled in Philadelphia as a nurseryman and seedsman and became the city's oracle on horticulture. His American Gardener's Calendar (1806) was the first thorough guide to the subject published in this country and remained a standard for half a century. McMahon, who took a special interest in the viticultural work of the company, now decided that a change was required. A new superintendent was appointed to oversee the company's vineyard in place of Legaux, but after a year Legaux had the bitter satisfaction of reporting that the man had bungled the job, the vines being pruned so badly that they would produce no grapes at all that season.[30] The dispirited stockholders were now ready to relinquish the entire thing back into Legaux's hands, while retaining title to the land and requiring that Legaux continue to keep up the vineyards. This Legaux was eager to do, but his eagerness had no reward. In the year after his restoration, the vines were devastated by a plague of caterpillars, and at the end of 1813 Legaux made this desolate entry in his journal: "No horses nobody no money and any assistance whatever to expect; what I shall do??"[31]

It is perhaps just as well that the journal for 1814-22 is missing; it could only repeat the tale of hapless vicissitude already clear enough. When the journal resumes in 1822 we hear no more of winegrowing. Legaux is old and ill, more inter-

ested in recording the details of the weather (a lifelong obsession with him) and in collecting information on the diseases that went round the neighborhood than in the state of his vines and the hope for a good American wine. His property at Spring Mill, though it had several times been put up for sale by the sheriff for debt, had at last been rescued by Legaux's son-in-law,[32] and there, in 1827, Legaux died, his dream of the Vineyard Company long since vanished. The forty years of vine growing at Spring Mill seemed to have led to nothing.

Other Pioneers in the Early Republic

Nevertheless, Legaux's name figures prominently in the efforts around the turn of the century that helped to determine what the actual course of successful American viticulture would be. The news of his vigorous, well-advertised, confident activity in its early years had the effect of stimulating others to a renewed attack on the great and still baffling puzzle of how to make an American wine. Legaux's nursery thus became the starting point from which a number of other vineyards grew and the source from which the historically important Constantia or Cape grape was distributed throughout the East. A contemporary eulogist of Legaux's states that the nursery at Spring Mill had furnished the vines for other vineyards not only in Pennsylvania but in New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky.[33] Some of these can be identified: Johnson's in New Jersey has already been mentioned; Dufour's in Kentucky will be taken up shortly; and one, at least, in Pennsylvania has left a name. This was the vineyard of Colonel George Morgan, whose claim was to have planted the first cultivated vines west of the Alleghenies at his property Morganza in Washington County, Pennsylvania, on the western edge of the state. One authority dates this modest undertaking in 1796;[34] more likely, it did not begin until early 1802, for on 11 December 1801 Morgan wrote to Legaux requesting a shipment of 2,200 cuttings of "Champaign," "Burgundy," and "Bordeaux" vines.[35] Morgan called his work "an adventurous and expensive experiment," and he hoped by it to "render to my country more service than by a thousand prayers for its peace and prosperity, which I daily offer."[36] But he had the pioneer's inevitable result: only 84 of the vines sent by Legaux survived into 1803, and the vineyard was given up in 1806.[37]

The influence of Legaux's example extended even into Maine, where trials with grapes were made by the Englishman Benjamin Vaughan. Vaughan, a prominent sympathizer with the colonial cause in England before the Revolution, had helped with the peace negotiations between the Americans and the English; later he had had to flee England to revolutionary France, where he was imprisoned. After his release he had migrated to Hallowell, Maine. There, though he became a correspondent of, and adviser to, American presidents, he took no active part in politics but devoted himself to literature and to agriculture. Vaughan obtained grape vines from Legaux in 1807, and in that year wrote to his brother in Philadelphia asking

for more cuttings, adding, "I can dispose of hundreds of cuttings for you, and make you a nice vineyard."[38] Vaughan persisted long and hopefully, for in 1819 he took the trouble to compile notes on wines and vines;[39] these are disappointing in their failure to comment on his experience, but something of what that had been is clearly implied by Vaughan's recommendation of native rather than imported vines.

Another positive result of Legaux's activity was to secure the interest of Dr. James Mease (1771-1846), a prominent Philadelphia physician and writer. When the Vine Company was promoted, Dr. Mease became one of the managers. A man of science, he had a technical as well as a commercial interest in the possibilities of grape growing and did what he could to advance the understanding of the subject. In 1802, when he was preparing a revision for American publication of an English work called the Domestic Encyclopaedia , he invited the Philadelphia botanist William Bartram to contribute an article on the native grapes of the United States. Bartram's article describes four species and three varieties of American origin. It was, of course, seriously incomplete, and did not clear up the confusions of nomenclature created by the great Linnaeus himself in naming the American vines, but it was the first published attempt to bring some order to the subject in this country.[40]

Mease himself extended Bartram's article by summarizing various authorities on viticulture and winemaking; he made a genuine attempt to consult local experience, citing Legaux, Antill, and Bartram as well as the more usual eighteenth-century French and English writers. Mease had the missionary zeal so common among the early propagandists: though he thought that the luxurious dwellers in the American seaports were probably too far gone in corruption to be able to leave their foreign wines, he hoped that the pioneers beyond the mountains would turn to making their own wine from native grapes. Mease recommended the Alexander (did he know that it was the same as the grape his associate Legaux called the Cape?), the Bland (another early native hybrid, from Virginia), and the southern bull grape (the muscadine).[41] By taking this position, Mease has been credited with "the first public utterance condemning the culture of the Old World grape and recommending the cultivation of native grapes."[42] This is not strictly true—we have seen that Estave in Virginia and the Society of Arts in London were both on public record in favor of the native grape before the Revolution, not to mention the many individuals from the earliest days who thought, either by logic or experience, along the same lines.[43] Mease's recommendations have, at any rate, the merit of being particular and had behind them more weight of authority than belonged to any earlier writer. His essay deserves Hedrick's compliment as "the first rational discussion of the culture of the grape in America."[44] Mease evidently hoped to expand his Domestic Encyclopaedia essay into a comprehensive treatise, for in 1811 he was at work on a "Natural History of the Vines of the United States," to be published with colored engravings.[45] There is no record of the publication of any such work, however.

The opening of the regions to the west of the original colonial settlements,

which proceeded apace after the Revolution, certainly helped to stimulate fresh experiment, as in the instance of Colonel Morgan. Another, earlier, one had been made by Frenchmen along the Ohio, though Morgan evidently did not know it—his own experiment, he thought, was the first trans-Allegheny trial of grape growing. But before him, in about 1792, the unlucky Frenchmen who had been tempted by the blandishments of the Scioto Company—a land speculation that was for a time the rage of republican Paris—had taken up the cultivation of the native vines they found growing on the islands of the Ohio River near their settlement of Gallipolis. These vines, so they imagined, were the offspring of vines planted by the French at Fort Duquesne (built in 1754 on the site of Pittsburgh and burned in 1758); they thought that bears, who are fond of grapes, might have dropped the seeds and so have spread them along the banks of the Ohio.[46] Another fanciful explanation held that the French soldiers of Fort Duquesne, in order to deprive the British of the luxury of their vines, rooted them out when the fort fell to the enemy and threw them into the river; in this way they were washed down to the islands off Gallipolis.[47]

The writer who skeptically recorded this story did so as an instance of the unreliability of tradition among illiterate men; but there is something touching about this wish to see a French element in the utterly un-Gallic environment of Gallipolis. Visiting the damp, shabby, struggling settlement in 1795, the French historian Constantine Volney found that the round red grapes being cultivated for wine there produced a drink very little different from that yielded by the huge and undoubtedly native vines of the woods. The settlers, whatever their ideas about the origins of their vines, were under no delusions as to the quality of the wine they made, calling it, Volney tells us, "méchant Surêne ."[48] The wines of Suresnes, near Paris, were a byword for sourness; a méchant Suresnes would thus be a superlatively thin and sour wine. It was, incidentally, probably a straggler from the colony at Gallipolis who was reported in 1796 to be making wine from the sand grapes (Vitis rupestris ) at Marietta, further down the Ohio.[49]

There were other Frenchmen who, despite such discouraging results as those at Gallipolis, continued to think well of the winegrowing prospects in this country. One of the earliest publications on viticulture in the new republic appeared at Georgetown about 1795 as A Short and Practical Treatise on the Culture of the Wine-Grapes in the United States of America, Adapted to those States situated to the Southward of 41 degrees of North latitude . This rare treatise, a single oversize leaf printed on both sides, was the work of a Frenchman named Amoureux, who was employed in an American merchant house but was hoping to take up viticulture in the developing settlements to the west—Kentucky, for example.[50] Amoureux's discussion, based wholly on European conditions, could not have led to practical results, but it is symptomatic of the interest that arose when the United States was new and hopes for all sorts of enterprise were high.

Another, slightly earlier, French contribution to the subject of American wine-growing had been made to a very different purpose by Brissot de Warville, whose

visit to Legaux at Spring Mill has already been mentioned. Brissot, who had been in America on an antislavery mission, one of the earliest of such efforts, published an article in the American Museum in 1788 arguing against the development of a wine industry in the United States. Winegrowing only produced wretchedness, Brissot explained; for every man who was enriched by the trade, many more were reduced to poverty by its harsh necessities, which only the capitalist could cope with. Why not let the French bear the burden?[51] Since Brissot was manifestly French, this argument may have failed of its full force. It is, however, interesting to speculate about the reasons held to justify making such a statement in a country where after two full centuries of settlement no one had yet succeeded in making wine in any quantity.

Dufour and the Beginning of Commercial Production

With the appearance of Jean Jacques Dufour—or John James as he came to call himself in his American years—this history takes a new and positive turn. Dufour (1763-1827) was a Swiss, born in the canton of Vaud to a family long engaged in winegrowing. As a boy of fourteen, so he wrote years later in his history of his own work, he had been struck by reports of the scarcity of wine in the United States and had resolved some day to go there and do something about it.[52] The anecdote is revealing. Dufour was, it seems, one of those deliberate characters who can form a resolve and then stick to it, no matter what the obstacles and no matter how many years might intervene between the idea and the execution. It was just this power of perseverance in the service of a single idea that the cause of American winegrowing had to have. There had been any number of clamorous proclamations of assured certainties before; there had even been enthusiasts who persisted year after year, as Legaux had done. But no one yet had had quite the singleness of purpose and stubbornness of Dufour.

He began by studying viticulture in Switzerland in order to prepare for his call, and in 1796, at the age of thirty-three, he set out for the United States. It must have seemed an anxious gamble. Though not exactly impoverished, Dufour had very little money; as the eldest son, he was the hope of a large family; and he would not have impressed an observer as the ideal man for the hard labor of the pioneer, for, whether by accident or congenital deformation, Dufour's left arm ended at the elbow.[53] After his voyage in the steerage, Dufour, with characteristic thoroughness, at once set out on a survey of what had been done before him towards winegrowing in the new states and in the territories beyond. In the next two years he managed first to make personal inspection of all the vineyards around New York and Philadelphia; all, he found, were unworthy to be called vineyards, except for "about a dozen plants in the vineyard of Mr. Legaux."[54] Discouraged to find that things were even worse than he had imagined, Dufour then set off for the West to discover whether that region held any promise. Having heard someone in Phila-

29

Certificate of a share in the "First Vineyard" of John James Dufour's Kentucky Vineyard Society.

Though the act of incorporation is dated 21 November 1799, the society was organized earlier, and

Dufour had already planted vineyards. By 1801 they were already beginning to fail, and the stock

of the company was never fully subscribed. (From Edward Hyams, Dionysus: A Social History

of the Wine Vine [1965])

delphia say that the Jesuits had productive vineyards at the old French settlement of Kaskaskia, on the river below St. Louis, Dufour dutifully made his way to that spot. There he found the remnants of the Jesuit asparagus bed, but the forest had swallowed up the vines: such, more or less, was the condition of almost all of the sites that Dufour had been told to see. Turning back east from St. Louis, he was led to Lexington, Kentucky, then the largest settlement in western America, the "Philadelphia of Kentucky" and the "Athens of the West," where enough professional men and merchants were already gathered together to support interest in wine-growing. Dufour was able in a very short time to organize the Kentucky Vineyard Society, a stock company modeled on Legaux's Pennsylvania Vine Company, which Dufour must have studied with interested attention.[55] The young Henry Clay, newly arrived in the booming town of Lexington, was the society's attorney and one of its subscribers.[56]

With the expectation of $10,000 in capital from the sale of two hundred shares at $50 each, Dufour, without waiting for the subscription to be completed, went into action. First he arranged for the purchase of 633 acres (and five slave families) on the banks of the Kentucky River at Big Bend, twenty-five miles west of Lexington. Then, early in the next year, 1799, Dufour travelled back to the Atlantic coast to collect vines for planting on the society's land; some he obtained from Baltimore and New York, but the bulk of his purchases were from Peter Legaux at Spring Mill—10,000 vines of thirty-five different varieties at a cost of $388. With this precious freight loaded on a wagon, Dufour crossed Pennsylvania to Pittsburgh and so back down the river to Kentucky. The cuttings were planted on five acres of the new property, which was then given the hopeful name of "First Vineyard."[57]

The vines grew well in the first two seasons; in the third they began, most of them, to fail. Dufour, like those hapless vignerons imported into Virginia nearly two centuries earlier, must have wondered what sort of curse the country was under, where the flourishing of the vines was the prelude to their death. Meanwhile, the experiment was much talked of in an expansive and confident way by its backers and by the patriotic press, so much so that, in 1802, the French naturalist François André Michaux, in America on a mission of scientific inquiry for Napoleon's government, felt compelled to pay a visit to Dufour to see whether his vines really did pose a latent threat to the French wine trade. Michaux was relieved to discover that First Vineyard, even at so early a stage, was not a success: "When I saw them, the bunches were few and stinted, the grapes small, and everything appeared as though the vintage of the year 1802 would not be more abundant than those of the preceding years."[58]

The symptoms described suggest that the vines were afflicted by black rot. No doubt mildew and perhaps both Pierce's Disease and phylloxera were at work as well. But from the general wreckage of his hopes, Dufour managed to salvage something. He had observed that two, at least, of the thirty-five varieties he had planted showed superior vigor and promised to be productive.[59] These were the vines that Legaux called "Cape," a blue grape for red wine, and "Madeira," for white. What the second and less important of these grapes was it is now impossible to say. So many grapes have been identified with the vines of the Wine Islands and especially with those of the privileged Madeira that one can only guess at what grape is actually meant in any given instance. Since it survived, it was no doubt a native hybrid, and such scant evidence as there is suggests that it was the grape known elsewhere as Bland's Madeira. The blue grape was, on Legaux's say-so, a grape that he had received from South Africa, where it was the source of those legendary wines known as Constantia (the actual source of Constantia is the Muscadelle du Bordelais). Whether Legaux maintained this statement in good faith or not is, as we have already seen, a question whose answer we can never know now. Whatever Legaux may have thought, the "Cape" is in fact the native labrusca hybrid grape once called Tasker's grape, originating in the region of William Penn's old vineyard on the Schuylkill and better known after its discoverer, James

30

The Alexander grape, first of the American hybrids; it was

propagated and sold by Peter Legaux as the "Cape" grape,

and became the basis of John James Dufour's Indiana

vineyards. It spread to all eastern vineyards, acquiring

many synonyms (the name "Schuylkill" in this illustration

is an instance). The Alexander is now a historic memory.

(Painting by C. L. Fleischman, 1867; National Agricultural Library)

Alexander.[60] Legaux, to whom the Alexander owed its re-creation as a vinifera under the name of Cape grape, does not seem to have thought particularly highly of it at the time he sold quantities of it to Dufour. It was not even included in the vines listed in 1806 as under trial in the nurseries of the Pennsylvania Vine Company,[61] so that no importance seems then to have been attached to it. Within a few more years, however, as we have seen, Legaux recognized it as the only reliable variety of all the many varieties, foreign and native, that he had planted.

In defense of Legaux's good faith in calling a native labrusca a vinifera, it is important to note that the Alexander, unlike most pure natives, has a perfect (that is, self-pollinating) flower; every variety of unhybridized native vine bears either pistillate or staminate flowers that are, by themselves, sterile. Dufour himself was persuaded by this observation that the Cape was a genuine vinifera, and so he thought to the end, not knowing that the perfect-flowered characteristic is the effect of a dominant gene from vinifera that can enter into genetic combination; for all this was long before Mendel had provided any understanding of hybrid patterns. But Dufour's insistence that his grape was not a native probably owed much to sheer stubbornness. His half-brother, John Francis Dufour, stated publicly that the Cape grape was unquestionably a native variety;[62] if the elder Dufour denied this, he must have been holding out against strong evidence.

Once he had seen that only two vines gave him any hope, Dufour, with the decision of a practical man, determined to abandon the culture of all other varieties to concentrate exclusively on those two. First Vineyard was begun over again on this basis, and was made to yield at least a little wine: In 1803 Dufour's brother was despatched to Washington, D.C., leading a horse loaded with two five-gallon

barrels of Kentucky wine consigned to President Jefferson.[63] We also hear of a toast, given by Henry Clay after the florid manner of the day and drunk in Kentucky wine at a banquet of the Vineyard Society. This was to "The Virtuous and Independent Sons of Switzerland, who have chosen our country as a retreat from the commotions of war" and who were assured that the wine of Kentucky would drive all painful memory of the Old World away.[64]

That moment may have been—probably was—the high point of the Vineyard Society's fortunes. Dufour had begun his work before all the subscriptions were paid in; the disappointing history of the vineyard provided a reason for not paying any more, and by 1804 the society was wound up, still in debt to Dufour for expenses.[65]

Even before the failure of First Vineyard was clear, Dufour had begun to set up another enterprise, one that became the first practical success in American wine-growing. Dufour seems from the first to have had the intention, once established, of bringing his family and others from his native place over to this country, where they could live secure from the disruptions and damage of the Napoleonic wars. In 1800, inspired by the first promising year in Kentucky, he sent word for his people to come. Seventeen of them, his brothers and sisters, their wives, husbands, children, and several neighbors, arrived in Kentucky in July 1801. There they found that Dufour had already begun to shape his plan for them. Congress had just created the Indiana Territory out of the old Northwest Territory, where settlers might obtain land at $2 an acre. Even at this rate, a purchase was beyond Dufour's means. But he was attracted to the shores of the Ohio, which looked like a region naturally appointed for the growing of grapes, and in 1801 he petitioned Congress for what he called "une petite exception" in his favor.[66] If Congress would grant him lands along the Ohio in Indiana Territory and allow him to defer payment for ten years, he, Dufour, would undertake, at a minimum, to settle his Swiss associates there, to plant ten acres of vines in two years, and to disseminate the knowledge of vine culture publicly. This was a minimum: but, as Dufour assured the gentlemen of the Congress, he foresaw a time when the Ohio would rival the Rhine and Rhone—when "l'Ohio disputera le Rhin ou le Rhône pour la quantité des vignes, et la qualité du vin."[67]

Congress was sufficiently swayed by the prospect to grant to Dufour the "petite exception" that he sought. In 1802, by a special act passed to "encourage the introduction, and to promote the culture of the vine within the territory of the United States, north-west of the river Ohio," Dufour was authorized to take up four sections of land along the north bank of the Ohio, just inside the present boundary of Indiana where it touches Ohio, and was allowed not ten but twelve years in which to pay.[68] Dufour himself did not leave Kentucky for the new grant; with two brothers and their families he stayed on at First Vineyard, evidently still determined to persist with it. The rest of the small Swiss colony went down the Kentucky River to the Ohio and their land grant, which they named New Switzerland (it is today in Switzerland County). There, in 1802, they began planting Sec-

ond Vineyard with the Cape and Madeira varieties already selected by Dufour as the best hope of American growers.

In 1806 Dufour returned to Europe, ten years after his coming to this country, leaving the care of the Kentucky vineyards to his brothers.[69] The purpose of his trip was to settle the financial affairs of his family in Switzerland, especially with a view to paying off the debt on their Indiana lands. The dislocation of things in those days of protracted war could hardly be better shown than by the fact that Dufour did not return for another ten years! First, the English captured the ship on which he was a passenger and he was taken to England. Released, he made his way to Switzerland, but evidently the confusion of his and his family's affairs made it impossible to act efficiently—perhaps, too, Dufour was not reluctant to linger. The wife that he had married before leaving Europe for America had remained behind in Switzerland. Then the War of 1812 intervened. After such delay, he was compelled to petition Congress in 1813 for an extension of the time allowed for payment on his land grant,[70] and it was not until 1817, after his return to the United States, that the sum was paid.

In Dufour's absence the settlement at New Switzerland began to prosper. A first vintage was harvested in 1806 or 1807—the date is not certain—and for a number of years thereafter production rose pretty steadily through good years and bad: 800 gallons in 1808, 2,400 gallons in 1810, 3,200 in 1812. The greatest extent of vineyard—45 to 50 acres—and the largest volume of production—12,000 gallons—seem to have been reached about 1820.[71] By that time the Swiss of Vevay, as the town laid out in 1813 had been named, had acquired a good name up and down the Ohio. A Vevay schoolmaster was inspired by local pride to compose a Latin ode on the "Empire of Bacchus" to celebrate the accomplishments of the Swiss. It opens (in the English version provided by another Vevay classicist) in this lofty strain:

Columbia rejoice! smiling Bacchus has heard

Your prayers of so fervent a tone

And crown'd with the grape, has kindly appear'd

In your land to establish his throne.[72]

More sober commentators agreed that Vevay was one of the most interesting and encouraging of western settlements. The veteran traveller Timothy Flint wrote that he had seen nothing to compare with the autumn richness of Vevay's vineyards: "When the clusters are in maturity. . . . The horn of plenty seems to have been emptied in the production of this rich fruit."[73]

As a condition of their land grant, the Swiss at Vevay undertook to promote viticulture generally, and they honored the obligation, giving advice and instruction to those who sought it and distributing cuttings free. There is evidence that at least a few others in the region were able to imitate the success of Vevay. A Swiss named J. F. Buchetti, who was connected with Dufour's community, had, in 1814, a vineyard of some 10,000 vines, mainly the Alexander, at Glasgow, in Barren

County, south-central Kentucky. This was still extant as late as 1846, and had earlier produced wine that Dufour, no doubt prejudiced in its favor, had pronounced to be very good.[74] Besides Buchetti, James Hicks planted Cape and Madeira vines at Glasgow in 1814.[75] Another early Kentucky vineyard, that of Colonel James Taylor at Newport, across the river from Cincinnati, was described in 1810 by an English traveller as "the finest that I have yet seen in America." Taylor, a cousin of President James Madison's, made at least some wine for domestic purposes.[76]

As to the quality of the wine of Vevay, opinions vary according to the experience and loyalties of the critic. It was advertised in Cincinnati in 1813, where it sold for $2 a gallon, as "superior to the common Bordeaux claret";[77] a western traveller in 1817, buying at $1 a gallon at the winery door, found the wine "as good as I could wish to drink."[78] The candor of Timothy Flint (he was a preacher as well as a traveller and writer) compelled him to confess that the wine made from the Cape grape at Vevay "was not pleasant to me, though connoisseurs assured me, that it only wanted age to be a rich wine."[79] Flint's judgment is supported by the German visitor Karl Postel, who came to Vevay in the late, degenerate days of the vineyards and found their wine "an indifferent beverage, resembling any thing but claret, as it had been represented."[80] Whatever the quality of Vevay red—and the red wine from native grapes has always been less pleasing than the white—the producers sold all that they could make. Dufour wrote that people were at first unfamiliar with the flavor of native wine, but that by and by all came to like it, so that "consumption having pretty well kept pace with the product, old American wine has always been scarce."[81] What he might have said more to the purpose is that American wine of any age at all had always been scarce. But why they made red wine rather than white remains curious. The foxiness of such labrusca hybrids as the Alexander is intensified if the juice is fermented on the skins, and reduced if the skins are separated. White wine would be both better suited to the Swiss tradition and less strongly flavored.

While Dufour was absent in Europe, his brothers, in 1809, had finally abandoned First Vineyard, and gone to join the rest of the community on the Ohio.[82] When Dufour returned, then, he found the whole number of his family and friends around the new town of Vevay, where he himself built a house and spent the rest of his days. While he lived, he continued to work and the vineyards of the community continued to produce, though signs of decline were probably appearing among the vines before his death in 1827.

In the year before his death, Dufour published a book at Cincinnati briefly sketching his career as a pioneer of vine growing and embodying the fruit of his experience in this country. Called a Vine-Dresser's Guide , it may fairly claim to be the first truly American book on the subject. The works of Bonoeil, of Antill, of Bolling, and of St. Pierre are of course much earlier, but none of them has anything to say about an extensive experience of actual vine culture in this country. Adlum's book (see p. 145 below), though in some important ways genuinely American, and earlier than Dufour's by three years, is far more derivative. Dufour had earned his

31

John James Dufour was the first American winegrower to succeed in producing

wine in commercial quantities. This book, the fruit of his long experience of

winegrowing in the remote American frontier states of Kentucky and Indiana,

was published only a year before his death. (California State University, Fresno, Library)

authority; his readers, he wrote, might doubt some of his ideas, but that was because, as he wrote in his own special syntax, he had followed "the great book of nature, from which most all I have to say has been taken, for want of other books, and even, if I had them, among the many I have read on the culture of the vine, but few could be quoted, for none had the least idea of what a new country is."[83]

"For none had the least idea of what a new country is"—the observation, logically so obvious, nevertheless took generations of experience before its truth was fully realized.

Like all those who had earlier addressed the American public on this subject, Dufour urges the great blessing of viticulture—but with a difference, for he is more concerned with personal satisfaction than with transforming the economy and enriching the nation. He wishes specially "to enable the people of this vast continent, to procure for themselves and their children, the blessing intended by the Almighty; that they should enjoy, and not by trade from foreign countries, but by the produce of their own labor, out of the very ground they tread from a corner of each one's farm, wine thus obtained."[84] Such eloquence on the virtues of doing it oneself is very attractive, and suggests that the legion of home vineyardists and winemakers in America today might well choose Dufour for their patron.

Dufour also hoped that the grapes available to American winemakers could be improved. He was by no means satisfied with those that he had to work with. A letter from him in 1819 notes that neither the Cape nor the Madeira ever ripened properly at Vevay. They also suffered from exotic afflictions, including crickets; these, Dufour says, had to be picked off the vines at night by lamplight.[85] The poor Swiss must have felt themselves to be in a strange land indeed on those nights. In his efforts to get a better grape, Dufour himself, he tells us, had made many experiments in grafting vinifera to native roots, but without any success in producing a combination that could resist the endemic diseases.[86] He did not doubt that success could be had, however, and he urged that others with better means should continue trying. So, too, with hybridizing; that would have to be the work of others, but a work absolutely necessary if better wine were ever to be made here.[87]

It was, perhaps, a good thing that Dufour died the year after his book was published, for the wine industry at Vevay had not much longer to live. The immediate trouble was disease, especially the fungus diseases, of which black rot is the chief in importance, and against which today a program of spraying must be maintained. At that time, no one knew what to do. A less immediate, but still important, problem was the indifference of the second generation. To the pioneers—to Dufour and his brothers, and their friends the Mererods and the Siebenthals—who had come from Switzerland expressly to grow wine in a new country, that work was of central importance. The second generation easily lost interest; there were many other, and more secure, opportunities than winegrowing, with its heavy risks and cruel disappointments, and who can blame them if they took them?[88]

There was also the important fact that the wine was not very good, so that, when transport and commerce developed, the wine of Vevay lost the advantage

that it had when it was without competition. Nicholas Longworth wrote that when the Hoosiers and Buckeyes of the Ohio River country were at last able to get better wines, those of Vevay "became unsaleable and were chiefly used for making sangaree, for the manufacture of which they were preferred to any other."[89] Sangaree, incidentally, is one of those undisciplined concoctions that take many forms according to the inspiration of their compounder; we are familiar with it now in its Spanish form as sangria. In earlier times in America, however, the compound was any red wine, diluted with water or fruit juices, and invariably flavored with nutmeg. It is, clearly, no compliment to a wine to say that it was a favorite for sangaree. A frequently printed anecdote says that Dufour himself, on his deathbed, confessed that the wine of his Cape grapes was inferior to the wine from Longworth's Catawba grapes, a conclusion that he is supposed to have stubbornly resisted in his lifetime.[90] The anecdote, however, comes to us from a Cincinnati source and is therefore dubious. In any event, the wine industry of Vevay may be said to have died with its founder. The year after Dufour's death, the vineyards were described as "degenerated," and by 1835 they had effectively ceased to exist.[91]

Given all the confusions, misunderstandings, and wrong directions that had made the history of American winegrowing from the outset, it is appropriate that the basis of the first commercial wine production in the country should have been such a confused quantity as the Cape, or Alexander, grape, whose true name and nature nobody knew. The Alexander could not have made a good wine; not a great deal of that wine was ever produced at Vevay; and the winemaking enterprise there did not last beyond a generation. Nevertheless, it was with the Alexander grape, and at Vevay, that successful commercial viticulture and winemaking began in the United States. The time, place, and people deserve to be strongly marked and specially reverenced by everyone who takes a friendly interest in the subject.

The Spirit of Jefferson and Early American Winegrowing

The first decade of the nineteenth century was the period of Thomas Jefferson's administration; it is especially fitting that the early, tentative successes in American winegrowing should have occurred then, for Jefferson was, both in private and public, the great patron and promoter of American wine for Americans: in private, as both an experimental viticulturist and a notable connoisseur; in public, as the spokesman for the national importance of establishing wine as the drink of temperate yeomen and as the sponsor of enterprise in American agriculture generally. Agriculture was in his words "the employment of our first parents in Eden, the happiest we can follow, and the most important to our country."[92] As for wine, "no nation is drunken where wine is cheap," he had written in 1818.[93] America, he firmly believed, had the potential to yield wine both cheap and good: all that was wanted was "skilful labourers." No account of the history of wine in America is complete without at least a bare summary of "Jefferson and wine."[94]

We have already touched briefly on Jefferson's part in Philip Mazzei's Vineyard Society just before the outbreak of the Revolution. Soon after, Jefferson had been transformed from country gentleman and provincial lawyer into a world-famous statesman, but he had never lost contact with the soil of his own Monticello. Nor had he ever ceased to look for ways and means by which wine could be produced by American farmers. His extended residence in France as American minister from 1784 to 1789 greatly increased his knowledge of wine. An impressive number of pages in the edition of his Papers now appearing in slow and stately procession from Princeton is given over to his correspondence with French wine merchants and with friends for whom he acted as agent and counselor in their wine buying. He also had a collection of the finest French wines made for him by an expert, though whether they were shipped to Virginia does not appear. "Good wine is a daily necessity for me," he said,[95] and the documentary evidence of the trouble he took to secure the best and widest variety is ample proof of the assertion. He also made tours to the wine regions of France and Germany, where, with his habitual energy and curiosity, he questioned the experts and made copious notes, descriptions, and memoranda on the technicalities of viticulture and winemaking.

Jefferson was always ready to welcome a new enthusiasm, and his many remarks on wine show that he frequently changed his preferences: one year it was pale sherry that pleased him most and that he insisted on drinking exclusively; another year it was a light Montepulciano; another, a Bellet from the region of Nice; and yet another, white Hermitage. All of these loves were no doubt genuine, but as a connoisseur Jefferson was evidently as eager to be amused by a novelty as to be faithful to old loves. This propensity may help to explain some of the remarkable things that he had to say about American wines, remarks that will be noticed a little later.[96]

One of the first things that Jefferson did on his retirement from public life was to make a fresh attempt at vine growing: the thirty-five years of public activity that intervened between his part in Mazzei's experiments and his return to private life were only an interruption, not a change, in his purposes. By this time, however, Jefferson had had some experience of the wines that were beginning to be produced from improved varieties of the native grape. Dufour, it will be remembered, sent wine from his Kentucky vineyard to Jefferson. What he may have thought of that we do not know, but he has left a notable response to a sample of the wine produced by Major John Adlum in 1809 from the Alexander grape growing in Adlum's Maryland vineyard. This Jefferson praised in extravagant terms; he had served the Alexander wine to his friends together with a bottle of very good Chambertin of his own importing, and the company, so Jefferson told Adlum, "could not distinguish the one from the other."

Jefferson advised Adlum to "push the culture of that grape," and took his own advice by asking Adlum to send him cuttings to be planted at Monticello, calling himself a "brother-amateur in these things."[97] Adlum obliged, but the cuttings were long in travelling from Havre de Grace to Charlottesville; they arrived in bad

condition, and all subsequently died.[98] This failure ended Jefferson's hopes for some years, during which he made no more efforts of his own. But when, late in 1815, Jefferson was approached by a young Frenchman named Jean David, newly arrived with a scheme for viticulture in northern Virginia, the old enthusiasm flared up again.[99] Jefferson at first cautiously replied to David that he was now too old to work in the cause of American wine and advised him to approach other sympathetic gentlemen: Major Adlum, for example, or James Monroe, then secretary of state, Jefferson's friend and neighbor, who had "a fine collection of vines which he had selected and brought with him from France with a view to the making wine."[100] Jefferson also urged David to concentrate on the native grapes.

David's proposal had evidently set the old ambition to work again, despite Jefferson's protest that he was now too old to take up the work again. By January 1816 Jefferson had decided that he would like to try again for himself. He wrote to Adlum to ask for cuttings as he had done in 1810, saying that he had an opportunity for fresh assistance and reaffirming his faith in the native vine: "I am so convinced that our first success will be from a native grape, that I would try no other."[101] He hedged his bet a little, though, for a few days later he wrote to Monroe to ask for cuttings from Monroe's French vines.[102] Unluckily, after stirring up this old passion in Jefferson, David seems to have backed out. A strange letter from him to Jefferson in February 1816, just when Jefferson had hoped to plant vines, says that, as a loyal Frenchman, he had been struck by a "scrupule. " If he were to succeed in making America abound in native wine, as he had no doubt that he would, would he not be doing an injury to the French wine trade? What could ever compensate him for such a painful thought? Well, perhaps a premium from the state for his intended services to American viticulture would be an adequate reward? And so on.[103] The relation between David and Jefferson ended here, and the author of the Declaration of Independence, the governor of Virginia, the American minister to France, the president of the United States, and the founder of the University of Virginia was once again frustrated in the matter of making grape vines clothe the slopes of Monticello.

Yet he never ceased to believe that the thing might be done by others. On the founding of the Agricultural Society of Albemarle County in 1817, Jefferson drew up a list of its objects that singled out "the whole family of grapes" for the society's "attention and enquiry."[104] He was also heartened by the success of certain gentleman growers in North Carolina with the Scuppernong grape, a variety of muscadine. He had some of the wine from this source in early 1817, the gift of his son-in-law, who praised it as of "delicious flavor, resembling Frontinac"[105] (that is, the sweet wine of Muscat de Frontignan grapes produced in the south of France; it was a favorite of Jefferson's). Jefferson, who had the patriot's tendency to exaggerate the virtues of the native produce, went even further in praise than his son-in-law had ventured: Scuppernong wine, he said, would be "distinguished on the best tables of Europe, for its fine aroma, and chrystalline transparence."[106] Those not partial to Scuppernong wine will not be much impressed by this evidence of

Jefferson's taste. Probably, like his judgment of the Alexander wine sent to him by Adlum, the intent of the remark was to be encouraging rather than impartially judicial. But there is no question that he enjoyed Scuppernong wine. Five years later he was still praising it, describing it as "of remarkable merit" and repeating the conviction that it would earn a place at the "first tables of Europe."[107] He also took pains to learn the names of the best producers so that he could have access to a good supply.[108] For the problem was to get it unadulterated by brandy, Jefferson complained; most was so saturated in brandy as to be, he wrote, "unworthy of being called wine."[109] In fact, according to a description published in 1825, the product called Scuppernong wine was really not a wine at all but rather fresh juice fortified and preserved by apple brandy, in the proportion of three gallons of juice to one of brandy.[110] Another writer, in 1832, dismissed North Carolina Scuppernong as "a compound of grape juice, cider, honey, and apple brandy."[111] Nearly a hundred years later an investigator for the state of North Carolina found that this, or something very like it, was still the practice.[112] We should, therefore, call the Scuppernong wine of the old South not a wine but a mistelle or cordial. It is hard to see how Jefferson could ever have had it in a form worthy to be called wine, but perhaps he had something the secret of which is now gone. His liking for this wine was by no means unshared; according to one good source, Scuppernong wine was always served as a liqueur with the dessert at the White House on state occasions during the presidencies of Madison, Monroe, John Quincy Adams, and Jackson—"a never-forgotten piece of presidential etiquette."[113]

At one point during his years in France Jefferson had come to the conclusion that viticulture, at least as he observed it in prerevolutionary France, was not a good thing for the United States: the grower either had too much wine or too little in most years, and got little for his produce no matter what. The result was "much wretchedness among this class of cultivators." Only a country forced to take up marginal land in order to employ surplus population was properly engaged in winegrowing, and for the United States "that period is not yet arrived."[114]

This was not, however, a fixed conviction. After his return to the United States, he was always quickly responsive to any new trial of American winemaking in whatever quarter. Though he planted vines of every description—natives and vinifera both—at Monticello over a period of half a century (the earliest record in his garden book is in 1771, the last in 1822), there is no evidence that Jefferson ever succeeded in producing wine from them, and probably after a certain time he ceased even to hope very strongly in the possibility for himself. But he cared much that others should succeed, and, by virtue of his zeal and his eminence, can be called the greatest patron of wine and winegrowing that this country has yet had.

6

The Early Republic, Continued

George Rapp and New Harmony

A kind of appendix to the chapter of winegrowing history at Vevay is that of the German religionists at New Harmony in western Indiana on the Wabash River, some twenty-five miles from its junction with the Ohio. The Harmonists, as they were called, combine two familiar elements in the history of early American winegrowing, being both an organized migration of non-English peoples traditionally skilled in viticulture (most of them came from Württemberg, in the Neckar valley), and a religious community. Led by the German prophet George Rapp, who preached that baptism and communion were of the devil, that going to school was an evil practice, and that Napoleon was the ambassador of God, the Harmonists, whose main social principles were communism and celibacy, left Germany for the United States in 1803.

George Rapp himself had been trained as a vine dresser in Germany, and the main economic purpose of his community was to grow wine. Following the example of Dufour, they tried to secure an act of Congress that would allow them to take up lands along the Ohio for this purpose on favorable terms. Difficulties arose, however, and they were at first compelled to settle in western Pennsylvania, where they were unhappy to find the land "too broken and too cold for to raise vine."[1] They turned instead to distilling Pennsylvania rye whiskey in substantial quantities, but did not quite give up the plan of carrying on the culture of the vine. In 1807 they laid out a hillside vineyard in neat stone-walled terraces, the standard practice of their native German vineyards but a novelty in the United States.[2]

There they planted at least ten different varieties of vine, probably all native Americans: the Cape and the Madeira as grown by the Swiss at Vevay were certainly among them.[3] In 1809 the Harmonists put up a new brick building with a cellar designed for wine storage, and by 1810 they were expecting about a hundred gallons of wine from their vineyard, now grown to ten acres.[4] The carefully kept records of the society show $1,806.05 received in 1811 for the sale of wine, a remarkable—indeed highly questionable—figure, since we are told that their total production two years later was still only twelve barrels.[5] What were the Rappites selling in 1811? In any case, they thought well enough of their 1813 vintage to send some bottles of it to the governor of Pennsylvania, who shared it with some friends and reported that one of them, "an expert," had found that it "resembled very closely the Old Hock ."[6]

The Pennsylvania settlement, sustained by the well-directed combination of agriculture and manufacture, quickly grew prosperous; but it was not what they wanted. In 1814 Rapp made a foray into the western lands, found an admirable site with a "hill . . . well-suited for a vineyard," and determined to lead the community there to resettle.[7] The whole establishment of Harmony—buildings and lands, lock, stock, and barrel—was put up for sale, the vineyards being thus described in the advertisements:

Two vineyards, one of 10, the other of 5 acres, have given sufficient proof of the successes in the cultivation of vines; they are made after the European manner, at a vast expence of labor, with parapet walls and stone steps conducting to an eminence overlooking the town of Harmony and its surrounding improvements.[8]

In 1814 the move began to the thousands of acres that their disciplined labors had enabled them to buy along the banks of the Wabash. They brought cuttings with them from their Pennsylvania vineyards, some of which Rapp gave to the Swiss at Vevay, where he was well received on his way to his new domain.[9] Early in 1815 Rapp's community had planted their New Harmony vineyard; by 1819 they had gathered their second vintage, and by 1824, at the end of their stay on the Wabash, the Harmonists had about fifteen acres in vines producing a red wine of considerable local favor.[10] For the decade of their flourishing, roughly 1815-25, the two centers of wine production at New Harmony and at Vevay made Indiana the unchallenged leader in the first period of commercial wine production in the United States. The scale of production was minute, but, such as it was, Indiana was its fount. At New Harmony, as at Vevay, the successful grape was the Cape, or Alexander; they had also a native vine they called the "red juice grape."[11] The Harmonists naturally yearned after the wine that they had grown and drunk in Germany, and in the first hopefulness inspired by the hillsides of the Wabash, so obviously better suited to the grape than their old Allegheny knobs, they ordered nearly 8,000 cuttings of a whole range of German vines, including Riesling, Sylvaner, Gutedel, and Veltliner.[12] That was in 1816; more European vines were no doubt tried—another shipment was sent out in 1823, for example[13] —but of course

all were doomed to die. The only thing German about the wine actually produced at New Harmony was Rapp's name for it, Wabaschwein .[14]

The Harmonists knew that it would not be easy to establish a successful viticulture, since, as hereditary vineyardists, they understood the importance of long tradition. When, in 1820, the commissioner of the General Land Office made an official request for a report on their progress in viniculture, they answered that they had yet to find "the proper mode of managing in the Climat and soil," something that "can only be discovered by a well experienced Person, by making many and often fruitless experiments for several years." It was all quite unlike Germany, "where the proper cultivation, soil, and climat has been found out to perfection for every kind of vine."[15] On the whole, their experience in Indiana was a disappointment, a disappointment reflected in these interesting observations, written about 1822, by an unidentified diarist who had just paid a visit to New Harmony:

They have sent almost everywhere for grapes, for the purpose of ascertaining which are the best kinds. They have eight or ten different kinds of wine, of different colors and flavors. That from the fall grape, after a few frosts, promised to be good, as at the Peoria Lake, on the Illinois, where, it is said, the French have made 100 hogsheads of wine in a year.[16] But none has done so well as the Madeira, Lisbon, and Cape of Good Hope grapes. Here the best product is 3 to 400 gallons per acre, when in Germany it is 2 to 1500. They sell it by the barrel, (not bottled) at 1 dollar a gallon. Its flavor is not very good, nor has it much body, but is rather insipid . . . .

The culture of it is attended with so much expense and difficulty, while it is so much subject to injury, that it results rather in a loss than a profit . . . .

From all the experience they have had of it, they are only induced to continue it for the sake of giving employment to their people; and, although it does better than at Vevay and New Glasgow,[17] where it is declining, it will, they say, eventually fail, as it did in Harmony in Pennsylvania.[18]

Though they could not make German vines grow on Indiana hillsides, whatever else the Harmonists touched seemed to prosper—at least to the views of outsiders. The numerous travellers, American and foreign, who passed up and down the Ohio Valley in the decade of New Harmony all testify to the neat, busy, and flourishing air of the scene there: "They have a fine vineyard in the vale, and on the hills around, which are so beautiful as if formed by art to adorn the town," an Englishman wrote in 1823, "Not a spot but bears the most luxuriant vines, from which they make excellent wine."[19] How good the wine was in fact can hardly be known now, but one may doubt. One German traveller in 1819, though much impressed by the excellence of the New Harmony beer—"a genuine, real Bamberg beer"—was less pleased by the wine: "a good wine," he called it, "which, however, seems to be mixed with sugar and spirits."[20] The observation is one that could probably have been made of almost all early American vintages that aspired to any degree of palatability and stability: without the spirits the alcohol content would have been too low; and without the sugar the flavors would have been too marked

and the acid too high. Jefferson, too, complained about the difficulty of getting wine free of such sweetening and fortification.

Another German traveller, the aristocratic and inquisitive Duke Karl Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, called at New Harmony during the course of his extensive travels in 1826, just after the Harmonists had sold their community and moved back to Pennsylvania. They had left some wine of their produce behind them, which the duke described as having a "strange taste, which reminds one of the common Spanish wine." An old Frenchman whom the duke met at New Harmony told him that the Harmonists did not understand winemaking, and that their departure would allow better stuff to be produced. The remark probably says more about the relations between Germans and French than about actual winemaking practices. The duke carried his researches further, however, by visiting the newest and last of the Harmonist settlements; this was at Economy, Pennsylvania, where Rapp had taken his community to escape the unhealthy climate and the ill-will and harassment they faced on the remote frontier from the early, uncivilized Hoosiers. There, at Economy, the duke was served by Rapp himself with "excellent wine, which had been grown on the Wabash and brought from there; the worst, as I noticed, they had left in Harmony."[21] The morality of this conduct is a nice point, but however it might be settled, we know from it that the Harmonists took the trouble to select and specially care for their superior vintages.

Economy, a part of which is now preserved as a state park, lay on the Ohio just below Pittsburgh. As the first two Harmonist settlements had done, this third one quickly prospered; and as in the first two, this one also was furnished with a vineyard, and every home had vines thriftily trained along the walls on trellises of unique design. Within a year of the migration from Indiana, there were four acres of vineyards at Economy,[22] and they continued to be developed in succeeding years. A striking piece of information is that, after all the years of struggle at the two earlier sites, the Harmonists, on this their third and last site, were still persisting in trying to grow vinifera. A visitor in 1831, after noting the hillside vineyard at Economy, laid out in stone-walled terraces after the fashion of Württemberg, added that the vines had come from France and from Hungary.[23] If this were the case, and if they did not also plant some of the old, unsatisfactory natives, the Harmonists cannot have produced much wine at Economy.

Nevertheless, Economy itself did not merely continue to prosper after the death of Rapp in 1847; it was propelled into vast wealth through investments in oil and in railroads. In 1874 the historian of American communistic life, Charles Nordhoff, found the place in high good order, including "two great cellars full of fine wine casks, which would make a Californian envious, so well-built are they."[24] In 1889 the young Rudyard Kipling, on his way from India to England, looked in briefly on Economy and noted the contrast between its accumulating wealth and its declining vigor.[25] By that time, if the Harmonists still paid regard to winemaking, their pioneering work had long since been eclipsed by newer and more commercial efforts.

32

A rare item testifying to the interest in winegrowing among the Germans of Pennsylvania in the 1820s.

This reprinting at Reading, Pennsylvania, of a standard German treatise on winegrowing was published

by Heinrich Sage, who tells us that he went to Germany expressly to acquire information on the subject.

The title translated is Improved practical winegrowing in Gardens and especially in vineyards, with

instructions for pressing wine without a press . . . dedicated to American winegrowers by Heinrich B.

Sage . (California State University, Fresno, Library)

As for New Harmony on the Wabash, that had been sold in 1825 to the Welsh mill-owner and socialist Robert Owen, who intended to establish a revolutionary model community as an example to the world.[26] Too many theorists and too few organized working hands quickly put the experiment out of order, and the communitarian days of New Harmony ended two years after the shrewd and practical Rapp had peddled the place to the doctrinaire Owen. New Harmony today is notable among midwestern towns for its lively interest in its own past, but it has long since forgotten the "red juice grape" and its Wabaschwein .

Before the Harmonists had retraced their steps from Indiana, other significant ventures had been made in Pennsylvania in the new viticulture based on the Alexander grape. The pioneer in these was a Pennsylvania Dutchman named

Thomas Eichelberger, of York County, who, in an effort to put barren land to profitable use, engaged a German vine dresser and planted four acres of a slate ridge in 1818. By 1821 Eichelberger had a small vintage; by 1823 his four acres yielded thirty-one barrels and he had added six more acres. He planned to reach twenty. When the word got round that Eichelberger had been offered an annual rent of $200 an acre for the produce of his vines, there was a scramble to plant vineyards in the Dutch country. "There is land of a suitable soil enough in York county," one writer declared, "to raise wine for the consumption of all the United States."[27] The rural papers of the day are filled with calculations exhibiting the absolutely certain profits to be made from Pennsylvania grapes, and by 1830 there were, according to contemporary report, some thirty or forty vineyards around York and Lancaster.[28] Many amateurs throughout the middle states had also been inspired by the example of York County to attempt a small vineyard.