2

The Georgia Experiment

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the prospect of winegrowing in America was hardly any clearer than it had been a century earlier. The Virginians had tried, through many years of the century preceding, to lay the basis of an industry. The secret eluded them as it did the colonists of the Carolinas, who also made an officially sponsored effort, less prolonged and less intense than in Virginia. Alongside of these publicly encouraged trials, dozens, scores, no doubt hundreds of local, individual, and amateur experiments in vinegrowing and in winemaking had been attempted from the beginning to the end of the century up and down the entire length of the Atlantic coast. The scale of all this, however, was so small as to be hardly visible even on the narrow strip of early colonial America. The work, frustrated after a few years wherever it began, established no tradition; nor was there any possible coordination of effort and experience among the small, isolated, and widely separated colonial communities. For practical purposes, each hopeful projector of winegrowing in 1700 was just where his fellow-spirit of 1600 had been., except that the lapse of a century without effective good results in this business was bound to suggest doubts and difficulties to him such as the first settlers could not at once suspect.

Nevertheless, the prevailing ignorance meant that hope remained alive. For who could say that the next optimist might not succeed? True, European grapes. had not grown well; but since no one knew any reason why, no one could say that the wine grape could not flourish here. And, indeed, on this question, perhaps the most interesting one still for the future of American viticulture, the answers, four centuries after the beginnings of settlement, are not yet in. Whatever the truth may

finally appear to be as to Vitis vinifera in the eastern United States, the colonist at the beginning of the 1700s knew simply that the wild vine, as it always had, still flourished powerfully, that it must therefore be possible to grow some sort of grape for making wine, and that the enterprise was worth a try. Hope could thus persist, and the persistence, at the level of official policy, is best shown in the eighteenth century by the early history of Georgia, last of the original thirteen colonies.

Georgia, as every schoolboy knows, was to be a place where the potential of a virgin land was to be put at the service of philanthropy. In the idea of Georgia's chief founder, General James Oglethorpe, men who had no place and no hope under the system of the Old World might become prosperous and upright in the spacious system of the New. This was very unlike Massachusetts, a colony founded by stern sectarians who sought a place apart for the exercise of their exclusive religion; or Virginia, where the simple prospect of gain was a sufficient motive. There were, to be sure, other considerations in the founding of Georgia. Providing a bulwark for the English colonies against the Spanish to the south and the French to the west was one. Another was the familiar commercial policy of providing Britain with those commodities for which it depended on foreign sup-pliers—notably that familiar trio, silk, oil, and wine. But the philanthropic motive was the strongest in the public imagination.

To make sure that the refugees from old England should not be corrupted in their new Eden, there were to be no slaves and no rum in Georgia. The economic basis of the colony, so its philanthropic projectors imagined, was to be those two commodities whose charm, a hundred and fifty years after Hakluyt, was still irresistible—silk and wine. By producing these from land "at present waste and desolate" the paupers of England might—so the royal charter ran—"not only gain a comfortable subsistence for themselves and families, but also strengthen our colonies and increase the trade, navigation, and wealth of these our realms." [1] Silk was the principal object, but wine came right after it. An early propagandist for the colony, appealing to the ideal "Man of Benevolence" whose pleasure was to relieve the distressed, exhorted him to imagine what Georgia might quickly become:

Let him see those, who are now a Prey to all the Calamities of Want, who are starving with Hunger, and seeing their Wives and Children in the same Distress; expecting likewise every Moment to be thrown into a Dungeon, with the cutting Anguish that they leave their Families exposed to the utmost Necessity and Despair: Let him, I say, see these living under a sober and orderly Government, settled in Towns, which are rising at Distances along navigable rivers: Flocks and Herds in the neighbouring Pastures, and adjoining to them Plantations of regular Rows of Mulberry-Trees, entwined with Vines, the Branches of which are loaded with Grapes. [2]

The effort to realize this animating vision (the vine wedded to the mulberry suggests a specifically Italian model) began in February 1733, when the first settlers landed at the site of Savannah and set about laying out the town. One of

12

General James Edward Oglethorpe (1696-1785) founded Georgia as a place

where neither slavery nor strong drink was to be allowed, but where wine

growing was to be a basic economic activity. "We shall certainly succeed,"

he affirmed; but the best intentions were not good enough. (Artist unknown;

Oglethorpe University)

their immediate undertakings was to establish a public garden, or nursery, where they could grow and propagate the mulberries, vines, olives, oranges, and other plants upon which the Mediterranean culture that they dreamed of was to be founded. This public garden, or Trustees' Garden, as it was called, was planted on ten acres of land between the town site and the river, to the east of the town in a spot still known in Savannah as Trustees' Garden. [3] Less than a year after its establishment, one traveller described it as a "beautiful garden . . . where are a great many white mulberry trees, vines, and orange trees raised." [4] But the repeated assertions made through the troubled years of the garden's life that it was badly sited on barren ground seem closer to the mark: it stood, said one critic, on "a large hill of dry sand." [5]

Even before any colonists had arrived in Georgia, the trustees of the colony,

13

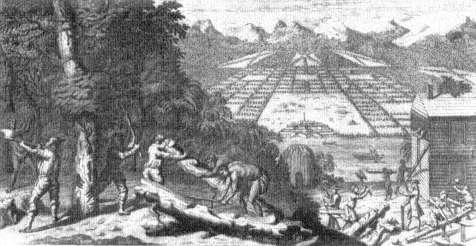

The Trustees' Garden, Savannah, Georgia, from a print published in London in 1733. Called

"the first agricultural experiment station in America," the garden was intended as a source

of grapes, mulberry trees, oranges, olives, and other plants for the new colony. (University

of Georgia Library)

eager to promote their plans for agriculture, had hired Dr. William Houston, a botanist of some distinction, one of the many correspondents of the great Linnaeus, to collect plants for trial in Georgia. Houston at once began his explorations by way of Madeira in 1732; from there he sent on "two tubs of the cuttings of Malmsey and other vines" to Charleston, to await the arrival of Oglethorpe's first band of settlers. [6] An agent was already in Charleston to supervise a nursery from which, in turn, the Savannah garden was to be supplied. The choice of Madeira as the source of vines for Georgia makes clear that the familiar logic of the argument from latitude was being applied. Savannah and the Western Islands lie within a degree of each other, and what more reasonable in theory—though false in fact—than that regions in the same latitude should yield the same produce? Dr. Houston intended to study the methods of vine cultivation and winemaking at Madeira too, in preparation for his arrival in Georgia. Unluckily, he fell ill at Jamaica and died there in 1733 without ever reaching the new colony to whose future he had hoped to contribute. [7]

Friends of the colony in England also helped: the famous gardener Philip Miller, in charge of the Botanical Gardens at Chelsea, sent a tub of "burgundy vines" late in 1733[8] (what the measure of a "tub" was I have not found, for it varied with the thing to be packed). A Mr. Charles King, of Brompton, who owned a vineyard there, sent not only three tubs of vines but ten dozen bottles of "Burgundy Wine" of his own manufacture—probably no Burgundian éleveur was aware of this suburban London rival—as a present to Tomochichi, chief of the local

Yamacraw Indians at Savannah. [9] King seems to have been the most persistent of the sponsors of winegrowing among the English friends of Georgia; from the trustees' records we learn that he sent another two tubs of vines in 1737 and, in the next year, a thousand vine plants. And there were other such gifts from other sources.

Such of them as survived the Atlantic voyage were set out in the Trustees' Garden, which seemed at first to flourish. The trustees were told in 1737 that the vines in the garden had succeeded extremely well, so that people "did not doubt of making good wines." [10] Two years later Oglethorpe reported that there was a half acre of vines in the garden, where they "have begun to shoot and promise well." [11] But that is the last hopeful note inspired by the garden: shortly afterwards a severe frost did grave damage, and that setback seems to have confirmed latent doubts about the garden's future. [12]

The garden was unlucky, in the way that the colony as a whole was unlucky. We have already seen that the first botanist appointed to advance the horticulture of the colony, Dr. Houston, died in Jamaica without ever reaching Georgia. His successor, Robert Millar, while collecting specimens of tropical flora in Mexico, was imprisoned by the Spanish on two successive voyages, his materials were confiscated, and he himself was finally returned to England empty-handed and without contributing anything directly to Georgia. [13] The first gardener actually to work in the garden, Joseph Fitzwalter, began enthusiastically, but then fell out with Paul Amatis, a Savoyard brought over by the trustees to develop the culture of silk. Amatis and Fitzwalter clashed over who was to be master of the garden. Amatis seems to have been a quarrelsome man, and at one time he grew so angry that he threatened to shoot Fitzwalter should he ever enter the garden again. [14] Early in 1735 Amatis had sent some 2,000 vines to the Savannah garden from the stock accumulated at Charleston. By July, he claimed, Fitzwalter had given some away as presents, to "I know not who," and had let the rest die. [15] Furthermore, the public character of the garden made things difficult: people stole the plants and stripped the fruit, to the despair of the gardener. "Fruits, grapes and whatever else grows is pulled and destroyed before maturity." [16] Amatis finally succeeded in establishing his authority over Fitzwalter, who left the colony for Carolina. Amatis himself died late in 1736, and in the decade or so of its remaining life, the garden saw several different gardeners come and go.

One of them, an educated Scotsman named Hugh Anderson, left a good description of the state and character of the garden and a plan for improving it. The soil was poor, he wrote to the trustees, and the site exposed to wind and sun. It would do very well as a nursery for mulberry trees, but if the trustees seriously wished to encourage "vines, olive trees, plant [sic ], drugs, etc.," they must create windbreaks, raise hedges to divide and protect the garden, drain the swampy land, build a greenhouse, dig a well, and set up a laboratory and a library. [17] The trustees must have wondered at what so simple an idea as a garden required in a strange new land.

By 1740 the garden was productive only as a nursery of mulberry trees, and it was clear that the main part of the tract was too sterile to suit horticulture. A rich, swampy section of the grounds was cleared and drained in 1742 to serve as a nursery for the vine cuttings that the trustees continued to send over to the colony, [18] and some rooted vines were distributed from this source in the years following. But the garden—"that barren place, where all labour was ill bestowed," as it was described in 1745—did not prosper. [19] Later in that year the gardener was fired for neglecting his charge, though he must have had a thankless task of it even had he been irreproachably conscientious. In 1755 the land, which had apparently long ceased to be employed as a garden, was, on his petition, granted to the first royal governor, John Reynolds. [20] Nearly two hundred years later an effort was made to reestablish a part of the original site as a museum and memorial garden, but its bad luck seems to have continued to pursue the spot, and the effort failed. [21]

The Trustees' Garden has been called "the first organized experiment station ever," [22] and is thus the prototype of an excellent institution. As a practical encouragement to winegrowing, however, it was no more successful than the Georgia trustees' hopeful prohibitions against slaves and spirits, both of which hopes expired in the same decade as the garden.

"All the vine kinds seem natural to the country" wrote one Georgia traveller in 1736; [23] it is the familiar observation of all early American travellers. There is a special pathos in this instance, though, since the writer, Francis Moore, is describing the vines of St. Simon's Island, only a few miles north of the Huguenot outpost in Florida where, it was alleged, the earliest American wine on record had been made in 1564. Now, nearly two centuries later, not much had changed: the Spaniards were still a threat, the vines still flourished mockingly, and the production of wine remained a dream.

At the same time that Moore was remarking the abundance of vines along the coastal islands, a more celebrated observer was taking notes on the grapes of Georgia: "The common Wild-Grapes are of two sorts, both red: the fox-grape grows two or three only on a stalk, is thick-skinn'd, large-ston'd, of a harsh taste, and of the size of a small Kentish Cherry. The cluster-grape is of a harsh taste too, and about the size of a white currant." [24] This is from the journal of John Wesley, whose labors at soul-saving in Georgia, where he had gone in the earliest days of that colony, were as troubled and unsatisfactory as the struggles of any Georgia vineyardist to grow wine. Back in England, John Wesley's brother Samuel had hailed the Georgia enterprise in a poem entitled "Georgia, and Verses upon Mr. Oglethorpe's Second Voyage to Georgia" (1736), in which the imagined vintages of Georgia are presented in glowing terms:

With nobler Products see thy GEORGIS teems,

Chear'd with the genial Sun's director Beams

There the wild Vine to Culture learns to yield,

And purple Clusters ripen through the Field.

Now bid thy Merchants bring thee Wine no more

Or from the Iberian or the Tuscan Shore;

No more they need th' Hungarian Vineyards drain,

And France herself may drink her best Champain

Behold! at last, and in a subject Land,

Nectar sufficient for thy large Demand:

Delicious Nectar, powerful to improve

Our hospitable Mirth and social Love. [25]

This outburst is a valuable expression of the attractive power that the vision of what may be called imperial winemaking had upon the sober English imagination, but it was a vision evidently much easier to sustain in the fields of Devonshire than in the woods of Georgia, where John Wesley encountered the "thick-skinn'd, large-ston'd" grape of "harsh taste" (evidently rotundifolia).

The hopes of Oglethorpe, the founder of Georgia, were not easy to defeat. He had supervised the laying out of the Trustees' Garden, and, despite the evidence to the contrary, persisted in his optimism. "We shall certainly succeed in Silk and Wine," he wrote to the trustees in 1738, and again, "there is great hope, nay, I may say, no doubt, that both Silk and Wine will in a very short time come to perfection." He was repeating the same confident assurances as late as 1743. [26] What reason did he have to make them? Probably none. But it is at least understandable that the founder of a colony in desperate straits, as Georgia was then, might feel himself bound to take a view opposed to all the plain evidence before him.

We learn hardly anything distinct from contemporary reports about the fate of the European vines that were actually planted in Georgia. Some say that those planted in the Trustees' Garden did well; others affirm that the vines were neglected or abused. Whether any were actually tended long enough to make it clear how they would do does not appear, but such information as exists makes that seem doubtful. As for winemaking in the colony, the few accounts make it plain that native grapes were always the source. Early in 1739, for example, a Mr. Cooksey told the trustees, who were naturally anxious to know something about the Georgia wines and vines that they hoped to promote, that he had himself "made wine of the wild grape of the country . . . but it grew sour, and would not keep, tho' very pleasant to drink when new, and of a fine colour." [27] Later in that year the trustees heard from Mr. Auspurger, their engineer and surveyor, just returned from the colony, that "he eat some grapes at Savannah in July as fine as can be seen, and he believed they would make the best Vidonia wine"[28] (Vidonia wine was the most highly regarded wine of the Canary Islands, a dry white wine exported to the English colonies as a minor competitor to Madeira).

Many miles to the south of Savannah, on St. Simon's Island, Colonel William Cooke, who had sent out sixteen different sorts of vine cuttings from France in 1737, had begun to make wine from native grapes (his French grapes would no' yet have been bearing—or, more likely, they had died). The result of Cooke's experiments was described to the trustees in 1740 by a Lieutenant Horton, one of Cooke's neighbors, as having "a pleasant sweet flavour and taste, and he believed

would keep near a year." Cooke's experiments, Horton added, made many in the southern part of the colony "determined to push on the plantation of vines." [29] Only a year later the trustees heard from a different witness that the impulse had come to nothing, "that some had planted grapes but left off, finding the grape small and unprofitable." [30] Still, where all was yet uncertain, one might hope to hear a very different story. Horton, for one, was still optimistic, for he was, in 1744, among those who received the 3,000 cuttings sent to the settlement of Frederica by William Stephens (of whom more in a moment). [31] Yet another colonist in 1741 told Lord Egmont, one of the trustees most interested in the fortunes of Georgia winemaking:

That the wine for export will certainly succeed in Georgia: that himself had made some even of the Wild grape cut down, which had as strong a body as Burgundy, and as fine a flavour: that by cutting the thick coat of the grape grew thinner, and if the cuttings were transplanted into vinyards or gardens, the Vine will every way answer still better. [32]

If the growing of good wine had any real chance in the conditions of early colonial Georgia, it would certainly have been found out by a gentleman sent over by the trustees as secretary to the colony in 1737. This was Colonel William Stephens (colonel of the militia, like so many colonels, English and American), a man already of advanced age for pioneering enterprise (he was sixty-six when he went to Georgia) and of rather tarnished fame. [33] Though he had represented the Isle of Wight in Parliament for twenty years, he was unlucky in business and had twice had to abandon home and position in order to flee from his creditors. Sent to Georgia by the trustees primarily to provide full reports on the colony, he became there an enthusiast of pure and holy fervor in the cause of the grape. He was always disappointed, but he deserves some memorial as the first official residing in the colonies to make a sustained attempt to realize the vision of winemaking so easily indulged at home in England but so heartbreaking to pursue in the wilderness.

Stephens also had the merit of keeping a journal—it was this habit that decided the trustees that he was the man to write the full and current reports they badly wanted—and from this journal we can learn in some detail of the hopes raised and the disappointments suffered in the struggle to make Georgian wine.

When Stephens arrived in November of 1737, he found both good news and bad news. The bad was that the vines in the Trustees' Garden were not doing well, and nobody could tell whether that was because the conditions in Georgia were wrong, or, as Stephens himself suspected, because of the "unskillfulness or negligence" of the gardeners. [34] The good news was that one grape grower, at least, was doing well. Stephens' journal for 6 December 1737 records the hopeful evidence:

After dinner walked out to see what improvements of vines were made by one Mr. Lyon, a Portuguese Jew, which I had heard some talk of; and indeed nothing had given me so much pleasure since my arrival, as what I found here; though it was yet (if I say it properly) only in Miniature, for he had cultivated only for two or three years past about half a score of them which he received from Portugal for an experiment; and by his skill and management in pruning, etc. they all bore this year very plentifully. [35]

The man Stephens calls Mr. Lyon was Abraham De Lyon, one of a number of Portuguese Jews, who, somewhat to the annoyance of the trustees, had been among the very first settlers in the colony. [36] Another member of this group, Senhor Dias, is said to have imported some vines in 1735, and when Dias died these vines came into the hands of De Lyon, with others that De Lyon had provided for himself. [37] By 1737 to judge from Stephens' enthusiastic report, the vineyard was flourishing and De Lyon committed to a serious effort at winegrowing.

So were other members of the Savannah Jewish colony; it was reported to the trustees in June 1737 that the Nunez family, to whom De Lyon was connected by marriage, wished to exchange their swampland holdings for dry land in order to plant vines (though one would suppose that they needed no special reason for wishing to make such a trade). One Isaac Nunez Henriques was most active in this business; "but all the family," the report went on, "are equally desirous with him to plant vineyards and each has made preparations for it, having vines ready to transplant and some in great forwardness." [38]

Perhaps it was the encouragement of Stephens that led De Lyon to petition the trustees for a loan of £ 200, claiming that he had already expended "the sum of four hundred Pounds in the Improvement of his Lot, and the cultivation of the Vines which he carried with him from Portugal, which he hath brought to great Perfection." [39] On 17 May 1738 the trustees ordered the money to be paid to De Lyon for repayment in six years' time. Less than a year later, in March 1739, Oglethorpe reported from Georgia that De Lyon had by then planted three-quarters of an acre of vineyard, "which thrives well," and that he had twenty acres cleared for fall planting. [40]

At this point something went wrong between De Lyon and Oglethorpe, and the encouraging beginning was stalled. In his letter to the trustees' accountant of 22 November 1738, Oglethorpe stated that he had, as directed, paid the £200 that had been authorized as a loan to De Lyon. [41] But evidently the transaction was not straightforward. A pamphlet published in Charleston in 1741 by a group of disgruntled Georgians alleged, among many other angry charges against Oglethorpe, that he had sabotaged the efforts of De Lyon. Just when De Lyon, they said, was ready to bring in both vines and vignerons from Portugal, Oglethorpe refused to hand over the money the trustees had authorized, and so the scheme failed. [42]

This cannot be the whole story, since De Lyon in fact gave his receipt for £ 100 of the money. [43] A more temperate explanation of what happened is given by Thomas Causton, the chief magistrate of Savannah, who informed the trustees that Oglethorpe had given directions for the loan to be paid, but that his agent had instead deducted from the sum a debt that De Lyon owed to the community store, and so De Lyon "was not able to perform his contract." [44]

Yet another, and anti-Semitic account, is given by the earl of Egmont, a trustee of the Georgia colony, who states that Oglethorpe determined to dole out the second £ 100 in small sums, "being desirous first to see how faithfully that jew would perform his covenants." [45] Whatever the reason, De Lyon literally wanted out. As

Stephens wrote in his Journal for April 1741, De Lyon had neglected his vines and had attempted to send some of his goods out of Georgia in preparation for leaving the colony. "I cannot," Stephens concluded, "any longer look on him as a person to be confided in."[46]

The Nunez family, one of whose daughters De Lyon had taken to wife, had all left Georgia for Carolina by September 1740 "for fear of the Spaniards" according to a contemporary chronicler, [47] and perhaps De Lyon, in wishing to follow them, had no more sinister motive than they had. The Portuguese and Spanish Jews in Georgia had known the persecution of the Inquisition in their native lands and had therefore a special reason to be frightened by a threat from Spanish forces. But another reason—one more ominous for the future of the colony—is given in the record kept by Lord Egmont of a conversation with a gentleman newly returned from Georgia in February 1741. His witness gave Egmont this sorry news:

That every one of the Jews were gone, and that industrious man Abrm. Delyon, on whom were founded all our expectations for cultivating vines and making wine.

I asked him the reason: he reply'd, want of Negroes, which cost but 6 pence a week to keep; whereas his white servants cost him more than he was able to afford.[48]

Since Stephens, writing two months after the date of Egmont's note, implies that De Lyon had not yet left Georgia, the statement that he had already done so is premature. But it was not long before De Lyon departed in fact, for we learn from the proceedings of the Savannah town council in October 1741 that De Lyon had by then been gone for several months, that he was not likely to return, and that his vines were "wholly neglected." The magistrates gave orders to "find out a proper person amongst the German servants to watch and look carefully after the said vines for the benefit of the Trust," but it is doubtful whether anything was actually done.[49] As for De Lyon, he took his family northwards and is afterwards heard of in Pennsylvania and in New York. A son of his returned to the South later, took a wife, and settled in Savannah, not as a vine grower but as a lawyer.[50]

One of the most frequently complained about difficulties in Georgia was that of getting good cuttings for planting. As early as February 1735 one colonist was begging the trustees that a "sufficient quantity of slips, etc. of vines may be delivered as against the next season. Had I enough ready I would plant now at least two acres." Two years later, the same writer repeated his request.[51] In December 1738, the trustees' records report, a parcel of vine cuttings, "mostly of the Burgundy kind," went out to Georgia by the ship America .[52] Stephens' journal tells us how they looked when they got there:

Among other things sent from the Trust by the ship America, lately arrived, was a parcel of vine-cuttings, which with proper care in packing would have been extreamly valuable, and are much coveted. But unhappily they came naked, without any covering, and only bound up like a common faggot; so that being in that manner exposed, and possibly thrown carelessly up and down in the voyage, they had the appearance of no other than a bundle of dry sticks.[53]

Despite this and other setbacks—successive shipments of cuttings from England all seemed to arrive dead or dying—Stephens remained sanguine. Early in 1740 his journal describes some very hopeful signs appropriate to the spring season: "One thing here I cannot but take notice of with some pleasure, which is, that I find an uncommon tendency lately sprung up among our people of all ranks, towards planting vines; wherein they shew an emulation, if they get but a few, of outdoing one another."[54]

By the end of the year, Stephens is even more emphatic. In his vindication of the colony, "attested upon oath in the court of Savannah, November 10, 1740," and intended to silence the critics of the government, he declared: "The staple of the country of Georgia being presumed, and intended to be principally silk and wine, every year confirms more our hopes of succeeding in those two, from the great increase (as has been before observed) of the vines and mulberry-trees, wherein perseverance only can bring it to perfection."[55] Still, seven years after the first settlement, hardly any wine seems to have been made, and the critics were growing loud. In a debate on supply in the House of Commons in February 1740, John Mordaunt, member for Whitechurch, sarcastically opposed a grant to the Georgia trustees on the grounds that their promises generally, and that about wine in particular, had not been made good: "As to wine, he believed it would be well to give it to the inhabitants for their own drinking, and wished them good luck with it, for it would be all would ever be seen of their wine, and if the people of the place drank no other, they would be the soberest subjects in the world."[56] Since the mercantilist argument of making England self-sufficient in wine was one of the most powerful appeals that the trustees had for coaxing money from Parliament, the inability to perform the promise was a serious matter.

A petition of December 1740, addressed to the king by a group of Georgians hoping to get slaves admitted to the colony, argues that the projected commodities of wine and silk would never be produced without slave labor. In all the history of the colony hardly any silk had been made, the petitioners affirm, and of wine, "not ten gallons."[57] Perhaps there had been a good deal more than that made, but not enough, certainly, to be anything more than a promising curiosity. We have already mentioned the vintages of Mr. Cooksey and of Colonel Cooke. In 1740, when Stephens was repeatedly assuring London that things were beginning to flourish, he was actually able to produce a bottle of wine for official tasting. In September of that year, Stephens left Savannah for Frederica, where Oglethorpe, whose time was more absorbed in fighting the Spanish of St. Augustine than in presiding over his colony, lay ill of fever. In his baggage, Stephens writes, "I had a bottle of Savannah wine at his service, made there, which I had brought with me, to present it with my own hand from the maker."[58] Next day the bottle—"a large stone bottle"—was presented to the ailing general for his judgment. He tasted it before the anxious Stephens and pronounced it to be "something of the nature of a small French white wine, with an agreeable flavor." Stephens adds, for our further assurance, that "all young vines produce small wines at first, and the strength and

goodness of it increases as the vines grow older."[59] Not everyone was so hopeful as Stephens, or so tactful as Oglethorpe. Major James Carteret, who was also at Frederica when Stephens presented his Savannah wine, later told the trustees that "he had tasted the wine made at Savannah which Col. Stephens carry'd from thence to Col. Oglethorpe, which was sad stuff, and bitter, rather the juice of the stalk than of the grape."[60]

By the next year Stephens saw even more reason for encouragement. People were actually competing with each other in establishing vineyards, he told the trustees in January 1741.[61] By May he was exulting in the flourishing condition of his own vineyard, in which "many of my vines, that had been of one or two years standing at most, made an agreeable prospect, by putting forth clusters of grapes in pretty good plenty, that had the appearance of coming to perfection."[62] The yield from the new vineyards was not yet enough to produce any substantial measure of wine, so Stephens suggested that three or four growers might pool their grapes, "whereby they might probably attain to a cask of wine, more or less sufficient to make some judgment of what they might expect in time coming."[63] By July, Stephens' eyes were gladdened by the sight of an actual vintage. James Balleu, a Frenchman from near Bordeaux, had had vines growing for the past three years at Savannah and was about to make wine from the crop. Stephens attended the occasion as an observer, and, he tells us, "had the satisfaction of seeing upwards of thirteen gallons press'd, and put into a cask for working; which from the richness of the juice, I should expect will become a wine of a good body, at a due age."[64]

That there really was visible activity in Savannah winegrowing, not just a fantasy of Stephens' hopefulness, is confirmed by Thomas Causton, whose survey of the "products of the colony of Georgia" made at the end of 1741, after noting the dereliction of De Lyon and the general difficulty of obtaining suitable cuttings, says that nevertheless "great progress has been made within this 3 years past." Winegrowing only needed "encouragement" in order to be established, and to this end he suggested a bounty of £100 "for the first pipe of wine which should be made in Georgia."[65] At the same time, Stephens was writing to the trustees' accountant in London that he would soon send a full statistical survey of the wine industry in Georgia, which would show how reasonable it was to expect success in winegrowing and would "convince every body, that all we have said, is not an empty Chimera."[66] The emphasis of the assertion suggests that Stephens had had to listen to loud and frequent doubts; and the skeptics were of course right. If Stephens ever prepared his promised statistical account, I have not found it. It could not have communicated much optimism to the trustees, for in the official defense of the colony prepared by their secretary in 1741, though it is said that the venture in winegrowing "shows a great probability of succeeding," it is prudently added that "this produce must be a work of time, and must depend upon an increase of the people."[67]

We know something of Stephens' own efforts as a viticulturist at this time; he,

at any rate, was working in good faith and with good hope. As part of his compensation from the trustees, Stephens had been granted a plantation of 500 acres (the maximum allowable under the rule for Georgia), some thirteen miles south of Savannah at the mouth of the Vernon River, which he named Bewlie, after an estate in England to which he fancied he saw a resemblance.[68] He seems to have planted grapes as soon as ground could be cleared, and his pleasures and troubles growing out of his vineyard at Bewlie make a major theme running through Stephens' journal. Early in 1742 Stephens, using cuttings taken from the Trustees' Garden in Savannah, made an extensive planting of vines under the direction of a man from the Swiss settlement at Purrysburgh (perhaps he was the Monsieur Rinck whom Stephens later called the most skillful vigneron in the colony).[69]

In April of 1742 Stephens was pleased to see that of the 900 vines he had planted that spring only a few had failed to grow. By 1743 he had 2,000 vines growing at Bewlie.[70] Despite the chronic difficulty of getting labor sufficient to keep up the plantation, let alone expand it, Stephens was able to look forward to a vintage in but a short time. The vines bore in their second year, but, on the advice of the unnamed vigneron whom he employed, the fruit was thinned so that the vines themselves would make better growth. James Balleu, of whom we have already heard, expected to make thirty gallons in 1743, and Stephens himself ordered a small experimental batch of wine made from his own grapes so that he might have some of the 1743 vintage to compare against the next year's promised production. "I found it of a stronger body than any I had yet met with," Stephens writes of his first wine, "a little rough upon the palate, and with a bitterish flavour, somewhat like the taste of an almond. The colour was of a pale red."[71]

By this time, the encouraging state of vine growing in Georgia began to attract the attention of neighboring South Carolina, where the thought of producing wine had never been entirely forgotten since the founding of the colony. In April 1743 Stephens reported a conversation that he had had with two Carolina men, who had told him that, if Georgia succeeded in growing vines, they would plant vines and encourage the industry in Carolina. Stephens was pleased by their interest, but then reflected sadly that Georgia, despite its head start, might be quickly overtaken since labor was so hard to get—Carolina, of course, had plenty of slaves for its rice and indigo plantations, and they might easily be made vine dressers as well.[72]

In January 1745, at a time when Carolina rice was glutting the market, Stephens heard rumors that the Carolinians were planning to go ahead with vineyard planting. Worse still, they had "seduced one of the most skilfull vignerons among the foreign settlers in Georgia to go and instruct them in their first planting."[73] Worst of all, certain Georgians, Stephens was told, had agreed to furnish vine cuttings from the stock available in Georgia. The stories were only too true. James Habersham and William Grant, prominent settlers both, sailed in February with 15,000 Cuttings and an unnamed vigneron for South Carolina, where they were to deliver their goods to a Port Royal planter. "But can such be looked on as good Georgian men?" Stephens asked his journal.[74] For himself, he was certain that he

would never raise up competition against Georgia. The fate of the Carolina vines does not appear, but Stephens probably need not have worried about them to judge from his own experience.

The crisis of Stephens' expectations came in 1744. He was able to distribute 9,000 cuttings from the pruning of his vineyard that spring, and had good reason to tell the trustees that "the propagation of vines seems to promise as one would wish." In the same letter he revealed his hopes, at the time of the vintage, "to press such plenty of grapes, as will give some specimen of what we may expect hereafter, both in quantity and quality."[75] The grapes ripened rapidly under the Georgia sun, and by the end of June Stephens was happy in the contemplation of a heavily laden vineyard. Called away to Savannah and kept there by his official business, he was thunderstruck to learn, just when he expected to hear news of a prosperous vintage, that his crop was ruined. His son and plantation manager, Newdigate Stephens, rode in to Savannah to give him the incredible news: "that plenty of clusters which hung so delightfully within a week past . . . now lay dropt off, and almost covered the face of the whole vineyard, half buried in dirt, and utterly lost."[76] There had been a storm of wind and rain in the week, though whether that would account for so catastrophic a destruction I do not know. Stephens responded with his indomitable optimism—he certainly had the true pioneer spirit and it is impossible not to wish that he had had better success: "If I live I'll persever and leave nothing in my power undone, that I think will conduce to the produce of wine in good perfection. The trifling quantity that is now fermenting, convinces me twill not want a reasonable share of those qualities most likely to recommend it."[77]

Some modest success was had by others that year, since Patrick Houston, early in 1745, was able to send to Oglethorpe a cask of what Houston described as "a pretty good Rhenish" made from vines growing at Frederica.[78] Probably they were native vines, though we are not told.

The next year, 1745, produced the same cycle of high expectation and crushing failure for Stephens. Once again the grapes at Bewlie grew promisingly. From the "pleasant show of plenty we now see on the vines," Stephens wrote, "I can do no less than entertain once more good hopes of what's to come."[79] But what came was utter failure, this time owing to the intense heats that scorched the grapes ripening in a Georgia midsummer; some, says Stephens, were "coddled" by the sun, while other parts of the bunch remained green and stopped growing. The affliction was general throughout the young vineyards of the colony, so that the year produced no vintage at all.[80]

Stephens' extant journal ends in 1745, though he remained as governor until 1751 and did not die until 1753. We do not know in detail what success he may have had in those later years, but it is not hard to guess. It does not appear that any wine worth sending to the trustees ever materialized, for their records mention no such thing. Wine was always something about to be, and all hope that the trustees entertained for a Georgian wine ended with the passage of the colony from their

hands to the royal government at the end of 1751. By that time there were slaves and rum in Georgia too, so that the original plans for a free, temperate, winegrowing plantation in the New World seemed to have been negated entirely. In the same year, 1751, the leader of the German colonists settled at Ebenezer, above Savannah on the Savannah River, wrote in response to a European gentleman's query "whether there are vineyards, or if there are none, whether it is considered possible to start any there?" that there were in Georgia "no vineyards": "The attempt has been made in Carolina and Georgia (I, too, tried in a ditch) to start wine gardens, and they did bear plenty of white wine after two or three years (the red wine was less successful) but died again [sic ] by and by. I assume that we do not know the way to plant and prune."[81]

The repeated failures between the establishment of the Trustees' Garden in 1733 and the disaster to Stephens' vineyard in 1745 had their inevitable effect. The hope of successful viticulture did not absolutely perish—it never did anywhere in the United States—and we hear, for example, in 1766, of two gentlemen named Wright who had begun a vineyard of twenty acres on the St. Mary's River.[82] But by 1771, John William De Brahm, who had earlier brought over a group of Germans to Georgia, reported that no one there, not even the Germans, showed any interest in working with the native vines that grew so vigorously all around them.[83] A final glimpse of the scene in Georgia is provided by the naturalist William Bartram, who, riding from Augusta to Savannah in January 1776, met an Irishman "lately arrived" on his way to cultivate wine grapes, grapes for currants and for raisins, and such items as olives, figs, and silk in the backwoods of the colony.[84] Whether this poor Irishman ever began his experiment, and if he did, how long he may have persisted, we do not know. The Irish are a hopeful race, but it was clear by 1776 to those not "lately arrived" that something more than hope was required.