Arkansas, Texas, and Oklahoma

South of Missouri, in Arkansas, the first winegrowing began as almost a repetition of the Missouri development: as Missouri had begun with Germans along the Missouri River, so Arkansas began with Germans (and Swiss) along the Arkansas River. The place chosen, around 1880, was at the high point of the territory along the river's course between Fort Smith, on the western border, and Little Rock, in the center of the state. This high point, logically named Altus, was planted in native varieties such as Catawba, Ives, and Cynthiana (a variety often claimed as native to Arkansas, and just as often asserted to be identical with Norton).[1] The beginning thus made has continued to the present day, and the firms of Wiederkehr and Post may now claim more than a hundred years of operation. The Cynthiana, by the way, is a variety of which we perhaps ought to hear more. According to Hedrick, it is not only a variety distinct from the Norton (so he settles that argument), it is "the best American grape for red wine."[2] This judgment was confirmed in the nineteenth century by the French in their experiments with native American grapes suited to the direct production of wine in Europe. Only a handful of producers now offer a varietal Cynthiana, three in Arkansas and three in Missouri.[3]

A distinctive note in Arkansas winegrowing is provided by the Italians of Tontitown, who varied the otherwise overwhelmingly German character of the industry throughout the Midwest and Southwest. Tontitown, in the far northwestern corner of Arkansas on the Ozark plateau, began as a refuge from a disastrous experiment. About 1895 the New York financier Austin Corbin conceived the idea that his vast

cotton-growing properties in the swampy flatlands along the Mississippi in southeastern Arkansas could be better worked by Italian immigrants than by the freed slaves who had been the only labor employed before. Accordingly he arranged to have Italians shipped out directly from Italy to the cottonfields of Arkansas.[4] Corbin's plantation was an island in the river, and, ominously, had been a penal colony, though now it was renamed Sunnyside.[5] There the Italians, despite their ignorance of cotton-chopping, met and surpassed all expectations as field laborers. They also met malaria, with fatal consequences: in one year at Sunnyside 130 died out of about a thousand.[6] By 1898 there was almost a panic feeling of desperation; they knew that they had to get out, but did not know how or where. At this juncture the priest of the Sunnyside church, Pietro Bandini, took charge. He entered into negotiations with the Frisco Railroad, whose lines ran through Arkansas and whose officers were eager to encourage agricultural development along their route. One of the properties proposed by the railroad was almost symmetrically opposite from the Sunnyside plantation: it lay in the northwest corner of Arkansas, at the other end of the state from Sunnyside, and it stood high in the Ozarks instead of at water level. The land was poor, but at least it would be free from malaria.

In 1898, under Bandini's leadership, some forty families of Sunnyside Italians made the exodus to the new lands; the men went to work at once in the zinc and coal mines of the region in order to pay the mortgage on the land, and in the intervals of their breadwinning began to plant vineyards. They were, most of them, from the Romagna and the Marches, and so at least by association of birth they were familiar with an immemorial winegrowing tradition. They named their settlement for Enrico de Tonti, the Italian who served as La Salle's lieutenant in the exploration of the Mississippi region, including Arkansas.[7] By degrees, through very hard work, and against much sullen and ugly local opposition,[8] the Italians made their way as farmers and winemakers. The town was not a communal experiment: each householder had his property to himself. But the experience of common origins, common suffering, and common achievement gave the Italians a powerful sense of community. Father Bandini, who had remained with his flock, was rewarded by seeing the growth of a small, but flourishing, town, which to a remarkable degree retained its original Italian character. By 1909 there were seventy families, all Italian, living in Tontitown. They were making wine from their vineyards of Cynthiana and Concord (a trial of vinifera varieties had quickly failed and was not persisted in); and they were soon to form a cooperative association for the marketing of their grapes.[9] In common with almost all the other grape-growing regions of the Midwest and East, the Tontitown vineyards were more and more given over to the production of table grapes, and then of grape juice. Prohibition, which put an end to winegrowing, nevertheless swelled the vineyards—now exclusively Concord—to record size, enabling the growers to survive and prosper but putting an end to the interest of the region from the point of view of this history.[10]

117

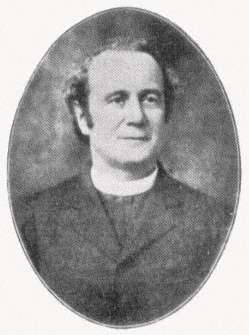

Father Pietro Bandini (1853-1917). the priest under whose leadership

Italian immigrants established Tontitown, Arkansas, and made it a

center of winegrowing. (From Giovanni Schiavo, Four Centuries of

Italian-American History [1952])

The ill-fated Sunnyside plantation was the source of two other small winegrowing colonies of Italians, both of these in Missouri. In Father Bandini's original negotiations with the Frisco Railroad, an offer had been made of land at Knobview, Missouri, along the route of the railroad as it ran southwest out of St. Louis. Bandini and that part of his flock who went with him to Tontitown rejected the offer, but a group of some thirty families closed with it and made the migration to Missouri in 1898.[11] Who the effective leader of the Knobview Italians was is not known—it would be interesting to identify who it was that took the initiative and made the crucial arrangements.[12] In any case, after hard days of struggle, the Knobview group, like that at Tontitown, began to prosper. At first many of them did track work for the Frisco in order to support their families while the slow work of agricultural development went on. Their town, which they later renamed Rosati, after the first bishop of St. Louis, did not flourish, most of its functions being absorbed by the neighboring town of St. James, so that Rosati lost its post office, its schools, and its stores. But the grape growing did well, so well that it managed to survive Prohibition and to serve as the basis for a newly revived winemaking industry around St. James in our day.

The third Sunnyside colony was the tiny town of Verdella, Missouri, consisting originally of only twelve families. They, too, devoted themselves to winegrowing, but beyond that their story remains obscure.[13]

In Texas, largest and among the most varied of the contiguous forty-eight states, the history of grape growing and winemaking was very much like what it

had been in the earliest days of colonization: full of unmistakable promise but hard to bring to success. Over much of the state, especially in the eastern half, wild grapes of many varieties abounded—indeed, one expert affirms that Texas has "the most diverse population of wild grapes in the world."[14] The explorer sent out by the U.S. government in 1857 to report on the grapes of the Southwest found that in parts of Texas the Mustang grape "is multiplied to an extent almost incredible."[15] The grapes and wines of El Paso, at the far southwestern tip of the state, went back to the first days of Spanish colonization, but, as we have seen, that start was not carried further after the annexation of Texas. Even before that annexation, German immigrants in eastern Texas made repeated trials of vinifera varieties, with the predictable result. Texas, like Missouri, was the scene of very early and considerable German settlement, otherwise rather unusual in the Southwest. Much of this settlement was organized by a group of wealthy men in Germany for speculative purposes, beginning in the early 1840s.[16] The colonists they sent out scattered over an area of southeastern Texas that now centers on San Antonio, and there they founded their towns, giving them such names as Fredericksburg, Weimar, and New Braunfels. At the same time, but under different sponsorship, a settlement combining Alsatians, Germans, and Frenchmen was made at Castroville, a little west of San Antonio.[17] The speculative hopes of the promoters of these places were not realized, but the Germans continued to come anyway. By 1860, it is said, there were some 20,000 of them in Texas.[18] Germans and Frenchmen alike hoped to make winegrowing one of their important businesses and almost at once set out vines brought from Europe. When these failed, they turned to the unimproved native grapes and made wine from them, sometimes in commercial quantities.[19]

The Mustang grape (V. candicans ) was the main variety used, and from all reports, it made a tolerable red wine, requiring added sugar but without the foxiness of labrusca.[20] Since it was so abundant a grape, it was natural to hope that it might also be a good wine grape. One Dr. Stewart, writing from Texas in 1847, reported that a "French wine maker and vineyardist" from Kentucky had come into Texas and pronounced the Mustang to be "the port wine grape, and of superior quality and yield." On this testimony, Dr. Stewart was moved to exclaim, "What resources our country possesses in this respect, if this be the fact, for the mustang grows every where in our fair land."[21] It is hard not to smile now, since the hope was so wide of the mark, but where little is known much may be hoped, and experts are not immune to the desire to please. It is probably also the fact that there are great opportunities for winegrowing in Texas that are only now beginning to be grasped.

The Mustang was the dominant native grape of Texas winemaking but not the only one used. Judge J. Doan, in the Texas panhandle, made well-regarded wine from a species of wild grape in Texas and Oklahoma Territory named after him Vitis Doaniana .[22] But such local and limited successes with the indigenous vines were disappointing when the early hopes had been to discover the Eden of the grape in Texas. Individuals continued to experiment through the rest of the century, trying all the native hybrids developed in the older eastern and southern states and gradually determining that the traditional southern varieties of aestivalis,

118

Thomas Volney Munson (1843-1913), of Denison, Texas, nurseryman,

grape hybridizer, ampelographer. For nearly four decades Munson produced

a steady stream of native hybrid grapes and showed by his work the possibilities

latent in the grapes of the American Southwest. (From T. V. Uunson, Foundations

of American Grape Culture [1909])

like the Lenoir and the Herbemont, seemed best suited to large parts of the state.[23] Nor did people entirely resist the seductive attraction of trying to grow vinifera: after all, such grapes were already long proven around E1 Paso. By the end of the century we hear of large plantings—200 acres—of vinifera around Laredo, on irrigated lands bordering the Rio Grande, of a group of Italians attempting to grow vinifera around Gunnison, Texas, and of a group of forty-seven French winemakers brought over by the Texas and Pacific Railroad to grow grapes in the alkali desert around Pecos.[24]

The more discreet growers contented themselves with the safer native varieties from the South, however: the oldest commercial winery now operating in the state, at Val Verde on the Rio Grande, goes back to 1883, and is still making its wines

from vineyards of Lenoir and Herbemont grapes.[25] The success of these and other related varieties led one of the persistent German growers of the state to declare that they "make of nearly the entire state of Texas a natural wine-producing region of enormous capacity."[26] By now we know that no claim to "natural" status is worth very much, but the proposition is an interesting one once again now that very powerful interests in Texas, including the university in its character as a great landholder, are investigating anew the chances of winegrowing in Texas.[27] That those chances were never realized in the nineteenth century is clearly affirmed by the French viticulturist Pierre Viala, who found abundant native grapes on his visit of exploration to Texas in 1887, but who noted that "Texas is one of the least viticultural regions of the United States."[28]

Apart from its wide open spaces, its abundant native grapes, and its large promise, Texas's greatest claim to attention in this history is the work of a single man, Thomas Volney Munson, of Denison, on the far northern edge of the state. Munson (1843-1913), a native of Illinois, was educated at the University of Kentucky and worked in Kentucky as a nurseryman for some years.[29] He was thus familiar with the many native vines of the Midwest and upper South, and began to take a keen professional interest in their possibilities. In 1873 he migrated to Lincoln, Nebraska, to continue his business as a nurseryman. He experimented with grapes in the frigid blasts and searing droughts of that country of extremes for a few years, but was then glad to accept the invitation of a brother to transfer his business to the north Texas town of Denison, on the Red River. This he did in 1876, and for the next thirty-seven years, until his death, he operated the firm of T. V. Munson & Son and indulged his passion for collecting, describing, and hybridizing native American grapes.

Like his good friend Hermann Jaeger, not far away in southwestern Missouri, Munson was an indefatigable field worker; for many years during grape season he rode on horseback through the woods and fields of Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma in quest of new varieties. Travelling by train, he carried his search into all but six of the United States and into Mexico, hunting, as he tells us, from train car windows, jumping off to collect specimens at every stop, scheduled or unscheduled.[30] Munson was active in assisting the French in their great struggle to understand and to exploit the characters of native American vines for their own ravaged vineyards. For his contribution he was made a chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1888. Munson also did notable work in the description and classification of native varieties and in publicizing the results of his work. He made an ambitious, comprehensive display of the native and foreign grape for the Columbian Exposition at Chicago, and he wrote several treatises on grape classification and grape varieties.[31] All this would have been work enough for a man who had his living to make as a practical nurseryman. But Munson's great passion was not for selling stock or for making classifications. It was for breeding native grapes. This is the work for which he is remembered today, work that he began soon after he removed to Texas and continued until his death. In that time he introduced about

three hundred new varieties, derived from crosses making use of a large number of native vines.

Munson's objects were several: for one thing, he tried to create a series of grapes ranging from early to late so that the whole of a growing season would be filled with successively ripe grapes. Like every American breeder, he dreamed of creating grapes that would defy the endemic national diseases—the rots and mildews that had oppressed American viticulture from the beginning. And he also aimed at creating a series of wine grapes suited to all the varying conditions of the country.[32] He accomplished none of these things, but the example of his energy and resourcefulness in the work was widely impressive. No hybridizer before him had provided so large and steady a stream of new varieties. There were so many, in fact, that Munson had difficulty in providing names for them; many are named for his family or friends, and others have singularly graceless names, suggesting exhaustion of the poetic power. Who would be tempted to drink the wine of "Headlight," "Lukfata," "XLNTA," "Armalaga," or "Delicatessen"? These and others are all recorded in Munson's Foundations of American Grape Culture , a retrospect of his work that he published in 1909.

One of Munson's distinctive additions to the repertoire of American grape hybridizing was his extensive use of native southwestern varieties, especially those of the species V. lincecumii (Post Oak grape), V. champini , and V. candicans (Mustang). It is fitting therefore that he should be especially honored in the South, as he has been in recent years. The eclipse of experimental grape growing during Prohibition meant that many Munson varieties almost disappeared from knowledge and were in some danger of disappearing for good. In the past decade, however, a small and enthusiastic group has devoted itself to rescuing Munson's work from oblivion. Led by W. E. Dancy, an Arkansas businessman and amateur grower, they have succeeded in discovering living instances of most of the Munson hybrids. They have also established a Munson Memorial Vineyard, where the Munson hybrids are grown and propagated, in his home town of Denison. Another tribute to him has been paid in South Carolina, where a "Munson Park" vineyard of thirty-three Munson varieties has been planted at the Truluck Vineyard of Lake City. It is even possible, still, to buy wine from Munson grapes: the Mount Pleasant Winery of Augusta, Missouri, offers red, white, and rosé wines made from the Munson variety Muench (named for the venerable Missouri German winemaker Friedrich Muench); and the St. James Winery of St. James, Missouri, makes (or did make) a dry wine from the variety called Neva Munson, after one of Munson's daughters. So Munson's name is still alive in the land, as are his grapes.

Oklahoma, or the Indian Territory, where Judge Doan found his supply of Vitis Doaniana for winemaking, was not without some production of its own. In 1890, only a year after the territory was opened to white settlement, Edward Fairchild, a transplanted winegrower from the Finger Lakes of New York, acquired land near Oklahoma City for a vineyard and orchard. In 1893 he constructed a substantial cellar of native sandstone, and there, for the next fourteen years, he

made wine for the local trade from Concord and Delaware grapes.[33] When Oklahoma Territory became the state of Oklahoma in 1907, it entered the Union as a Dry state. That put an immediate end to Fairchild's winemaking, and to any other such enterprises that had grown up in the brief history of Oklahoma settlement. It is a startling fact that, according to the census of 1910, Oklahoma had over 4,000 acres of vineyard, putting it eighth among all the states. Yet perhaps we ought not to be surprised. No less an authority than T. V. Munson pronounced Oklahoma to be a splendid grape-growing region.[34] In recent years the Fairchild Winery has been carefully restored and entered in the National Registry of Historic Places.[35] The restoration makes it possible to get an unusually distinct and accurate idea of the details of the actual operation.