Marketing Problems in the Late Nineteenth Century: The California Wine Association

The problems of viticulture and winemaking such as the university and the state board devoted themselves to were mostly manageable problems. Given time, they could be, and were, successfully worked out. Another, and more difficult, problem was how to sell the wine once it was made, a problem that became acute in the season of 1886. The decade had opened with the prospect of California's taking over the first position in supplying the world's wine, with the result that planting and production leaped up: the ten million gallons that California had produced in 1880 had soared to eighteen million in 1886. Yet, after all, European winemaking had not died. The heroic labor of the French scientists and officials had first checked, then reversed the decline of the vineyards, so that the vast export markets that Californians imagined were only briefly opened to them. Some expansion of markets had taken place in South America and the Pacific, and a beginning had been made in England.[48] The export of condensed juice as an expedient to evade the taxes on wine was also tried; we have already noted Shorb's experiments. These things were at best only palliatives, however, and could not avert a long depression of prices and sales.

Part of the problem, at least, lay in the failure of the California industry to impose itself upon the eastern trade. California wine lacked prestige as compared to anything imported, and the New York merchants wanted it only to supply the cheap market. Charles Wetmore charged that the New Yorkers in fact knew nothing about the possibilities of California wines, and that, since they never visited the state, they missed their opportunities to buy good wines before they disappeared into undistinguished blends for the standard market. On the other hand, Wetmore conceded, the Californians handled their own wines badly: uncontrolled secondary fermentations, storage under conditions of damaging heat, aging too long in wood, and other bad practices meant that the wines they shipped east would be heavy and dull at best and, at worst, simply spoiled.[49]

The failure to develop a market for wines of quality from California was particularly damaging to the industry, for it destroyed all incentive to take the trouble and run the risks required to grow the best varieties and to make the highest standard of wine. "The man who gets ten tons of grapes to the acre gets 10 cents for wine; the man who, on a steep hillside, gets two tons and a half, gets 12 cents; and the 12-cent wine is mixed with the 10-cent," said Charles Wetmore in 1894.[50] He went on to describe the languishing of the industry: growers were allowing diseases to run unchecked through their vineyards; some were grafting over their su-

perior varieties to high-yielding, low-quality kinds; and some 30,000 acres of grapes had been withdrawn from the state's total in the past six years.[51]

By 1892, for example, Zinfandel grapes sold for $10 a ton—not enough to pay the costs of picking. Wine at wholesale fetched 10 cents a gallon.[52] In such circumstances, the wish to eliminate competition in favor of some sort of cooperation, legal or otherwise, grew irresistible. At the lowest point of the industry's fortunes, in 1894, the decisive step was taken when seven of the state's largest and most powerful merchants, all based in San Francisco, joined together to form the California Wine Association (CWA). Together they represented much of the wine-growing history of California, and so large a part of the state's wine traffic that they at once dominated the market and continued to do so until Prohibition.[53]

The distinction between winegrower and wine merchant was not sharply drawn at this time in California. Most of the members of the CWA were vineyard owners, and all of them operated wineries that produced at least a part of what they sold. The association was thus in a position to operate a fully integrated enterprise, beginning with the grape and ending at the retail shelf, and this on a scale without precedent. Among the association's many and various properties from the beginning were such items as the Greystone Cellars at St. Helena, biggest in the state, the Glen Ellen Vineyards in Sonoma County, the Orleans Hill Vineyards in Yolo County, and the Cucamonga Vineyards in San Bernardino County. Other properties were absorbed into the system in ensuing years. By 1902 the CWA controlled the output of over fifty wineries, producing some thirty million of the state's forty-four million gallons of wine in that year. By 1910 a company brochure could boast that the association "cultivates more vineyard acreage, crushes more grapes annually, operates more wineries, makes more wine, has a greater wine storage capacity than any other wine concern in the world."[54] The company's wineries were scattered throughout every winegrowing region of the state: they included, to name but a few, the Uncle Sam Winery in Napa, the Tokay Winery in Glen Ellen, the Pacific Winery in San Jose, and the Calwa and Wahtoke wineries in Fresno County.

Their produce was sent to central cellars in San Francisco where the wines were stored, blended to a uniform standard, bottled, and then shipped for sale under the Calwa brand, with its trademark of a young Bacchus, accompanied by the California bear, standing at the prow of a ship whose sail bore the seal of California. Thus the idea of a standard, unvarying product bearing a brand identity was introduced into the California wine trade. The care of the cellars and the crucial work of blending was under the exclusive charge of Henry Lachman, famous as one of the two best tasters in the state (the other was Charles Carpy, also an official of the CWA).[55]

Retirement, death, business vicissitude, and the consequent sale of stock greatly altered the original ownership of the CWA, and after about a decade of operation, when it had proven its profitability, control passed into the hands of certain California bankers, notably those of Isaias W. Hellman.[56] Since Hellman, through his

100

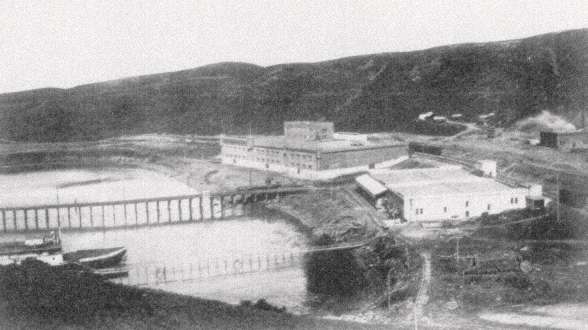

The imposing scale of the operations of the California Wine Association appears in its

headquarters building in San Francisco. The building was destroyed in the earthquake

and fire of 1906. (From a California Wine Association brochure, c. 1910; Huntington Library)

Farmers' and Merchants' Bank of Los Angeles, had been instrumental in financing such pioneer wineries as B. D. Wilson's and the Cucamonga Vineyards, his investment in the CWA made a link between the old phase of the industry, centered in Los Angeles, and the new, centered in San Francisco.

Well provided with capital, and strongly entrenched in the wine markets of the country, the CWA was able to withstand the catastrophe of the San Francisco earthquake, when the ten million gallons of wine in its cellars were lost to shock and fire.[57] A year later, the resilient company was building its final monument, a huge red-brick bastion on the shores of San Pablo Bay near Richmond. With its satellite buildings, it covered forty-seven acres and combined a winery, distillery, and warehouses. An electric railway threaded the premises, linking the docks where ocean steamers loaded, with the transcontinental railroad tracks on the land-ward side of the plant. The storage capacity of Winehaven, as this little commercial city-state was named, was originally ten million gallons, later raised to twelve million; besides the wine produced on the spot, Winehaven also handled the flow of wine that came in from all of the many outlying properties of the CWA.[58] From the turn of the century to the coming of national Prohibition, the CWA was the most prosperous establishment in the most prosperous period that the California wine industry had yet known. As a monopoly, or rather, near-monopoly, it belonged to

101

Winehaven, the central facility of the California Wine Association on the shore of San Francisco

Bay at Richmond, photographed in 1910. Winehaven was the phoenix which rose from the ashes

of the fire in 1906 that consumed the association's San Francisco headquarters. From its ten million

gallons of storage, wine was shipped by direct ship and train connection all over the country.

(Huntington Library)

the rapacious business style of the late nineteenth century, and, no doubt, if the full record could be known it would show a long tale of sharp practices and dubious moves. Whether the combination represented by the CWA was a necessary or even a particularly effective way to restore the California wine trade to health no one can say now. But its flourishing did coincide with a span of years in which prices remained fairly stable while production gradually gained.

The leading antagonist of the CWA was a rival organization dominated by winegrowers, as the CWA was dominated by wine merchants. In 1894, foreseeing that growers would be entirely at the mercy of the CWA unless some alternative home for their grapes could be found, a combine of growers and wineries formed the California Wine Makers' Corporation (CWMC).[59] The manager was the former secretary of the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, John H. Wheeler, and the main promoters were Andrea Sbarboro and Pietro Rossi, the leaders of the Italian Swiss Colony. Their plan was to contract for a large part of the California crop, have it made into wine by wineries outside the CWA network, and stored until such time as a favorable sale could be made. (It was to assist in carrying out

this plan that the famous giant cistern was built on the Italian Swiss Colony grounds at Asti.) In this way the CWMC could reasonably hope to negotiate with the CWA instead of helplessly accepting whatever terms the merchants cared to dictate. The CWA chose not to fight at first; it bought the corporation's wines at the corporation's prices in the first year of their dealings, 1895. Thereafter they began to draw apart, and by 1897 were engaged in full-scale war in the major markets of the country. The CWMC undertook to sell its own wines direct instead of through the CWA; the CWA responded by ruthlessly cutting prices. By 1899, when a short crop drove prices up for the whole industry, the CWMC was glad to take the opportunity to retreat. It was quietly dissolved in that year, and the field left open to the victorious CWA.[60]

Whatever else the CWA may have accomplished, it permanently transformed the idea of how California wine was to be sold. The trade in the early days had come to be dominated by the San Francisco merchants, whose practice was to buy the entire annual output of producers at a fixed price and then to blend it according to their own notions of what was suitable. On this system there was obviously no incentive for winegrowers to aim at making wines of special quality, since all went at a single price and all was blended so as to smooth out whatever peaks and valleys occurred in the produce of a given vintage. Later, as some individual growers grew large enough to handle their own production—including aging, blending, and shipping—they could set their own standards. Even then, however, most wine in California left the winery in bulk—in barrel, puncheon, or cask. And most such wine went from producer to large wholesalers in distant parts of the country, who might or might not know how to handle the wine properly, supposing, as must rarely have been the case, that they even had the facilities to do so. The wholesalers would label the wine as their own taste and experience dictated, or they could sell to a retailer who might then label the wine according to his own notions. The succession of intermediaries meant that the wine ran all sorts of risks in the handling, especially the risk of spoiling.

Even more prevalent, according to the dark imaginings of the California producers, was the risk of the wine's being adulterated. The claim that unscrupulous easterners adulterated California wine before selling it is a constant theme of the California winemakers, and an explanation for all the ills of the trade. No doubt much wine was injured in handling, but it does not follow that deliberate adulteration was a very frequent practice. George Husmann, writing from California in 1888, doubted that adulteration took place to the extent that his fellow winemakers claimed. Bad handling and bad methods were the real cause of trouble for California wine; so, too, was the "prevailing custom of selling whole cellars of wine, good, bad, and indifferent, to the merchant, and compelling him, so to say, to take a lot of trash, if he also wanted the really good wines a cellar contained."[61] This is interesting evidence that the merchant was not always the villain and the grower the innocent victim.

Growers also ran the risk of having their wines given French, German, or Ital-

ian labels. Robert Louis Stevenson tells in The Silverado Squatters of a San Francisco merchant showing him a cupboard filled with a profusion of "gorgeously tinted labels, blue, red, or yellow, stamped with crown or coronet, and hailing from such a profusion of clos and châteaux , that a single department could scarce have furnished forth the names"—and all to be used on innocent bottles of California wine.[62] There might be some French wine in the bottles so labelled. Henry Lachman, the pioneer San Francisco wine merchant and director of the CWA, recalled that for many years it was standard practice in San Francisco to blend California wine with French wine that had arrived as ballast in ships calling to load California grain for Europe.[63] Given the anarchic methods for distributing and identifying wine that prevailed through the nineteenth century, even the largest California producers had little chance to control the condition of their wines or to establish any kind of market identity and customer loyalty.

The system was not all bad, by any means. Since the small producer did not have to worry about marketing his wine, he did not have to develop a "line" and could therefore concentrate on producing what he did best. If he had a stable arrangement with a wine merchant, a sound and enduring reputation might be built up. But in general, the received pattern in California did not encourage the ordinary winegrower, or do much to make a reputation for the integrity of California wines.

The sheer size of the CWA's operations made it possible to change the prevailing system. The company could afford to store vast quantities of wine, to keep it on hand to insure uniform blending, and to advertise and distribute its own brand throughout the country. Calwa brand wines were bottled at the winery and sold only in glass;[64] if there was anything to object to in a bottle, at least the company stood behind it. Another forward-looking practice of the CWA was to avoid using European names for its wines. They might be described as "table claret" or "burgundy type" or "good old sherry type," but they were called by their own names—Winehaven, La Loma, Hill Crest, Vine Cliff. Not very imaginative, perhaps, but at least distinctive, and impossible to confuse with the wines of some other country. A few CWA wines were what we should now call varietals, and were identified as such: Vine Cliff, for example, was riesling; Hill Crest, a "finest old cabernet claret," selling, in 1910, for $8 a case.[65]

One of the unnoted casualties of the great San Francisco earthquake and fire was the plan of the CWA to mature specially selected California wines in its cellars to demonstrate to the trade what such care could do for the state's wines. These special selections were among those millions of gallons of wine destroyed in the fire, and the loss, according to a rival eastern winemaker, was "one of the greatest calamities that ever visited the California wine business."[66] Such wines, if they had survived to be distributed, would have made the reputation of the state, according to one who had been privileged to taste, a decade later, a few of the bottles that had escaped the general destruction.[67]

The CWA carried on an export program under the "Big Tree" brand of Cali-

102

The list of Calwa wines around 1910; these wines, blended to standard and bottled

at the winery, were available for national distribution. Customers could, however,

order wine from the California Wine Association in five-gallon casks or larger

containers, freight prepaid to "the nearest main line railway depot." (From a

California Wine Association brochure; Huntington Library)

fornia red and white wines, familiar items of commerce in England by the end of the century. "Big Tree" wines, sold in fiat-sided flagons of brown glass with the image of a huge sequoia stump blown in relief on one side, were advertised in the catalogue of London's elegant Harrod's store in 1895 thus: "Zinfandel, good table wine . . . very soft and round and free from acidity, most wholesome and bloodmaking," at 18 shillings a dozen. One notes the typical English recommendation—"most wholesome and bloodmaking"—on grounds of health rather than of pleasure. The number of old "Big Tree" bottles still available for sale in antique shops and at jumble sales in England attests to the success of the approach.

With the establishment of the California Wine Association, the wine industry in California had acquired the shape that, with little essential change, would continue down to the advent of Prohibition. The dominance of the CWA was such that its old competitors were absorbed into the system—notably the Italian Swiss Colony, which had been instrumental in forming the rival California Wine Makers' Association in 1894. By 1901 it was ready to slip quietly into the fold of the CWA. It retained, to all external appearances, its old identity, but its policies were now those of the CWA.[68]

Though it controlled the market by the power of its size, the CWA did not prevent others from joining the trade; there were, for example, 187 winemaking establishments in California in 1900 (the figure does not take account of the many farm producers), a considerable increase over the 128 in 1890, and most of these new establishments would have been created after the formation of the CWA. The figure of 181 reported in the 1910 census shows only a marginal decline from the point reached in 1900. Almost all of the new establishments would have been small enterprises, exploiting local markets and thus almost invisible on the national scale of the CWA's operations. The extent to which winemaking was still a domestic occupation is suggested by the national census of 1910, which reported that wine and grape juice were manufactured on 2,163 farms in California in 1909. One quite, large firm did arise in this period, however, the Italian Vineyard Company of Secondo Guasti, on the sandy slopes of the Cucamonga district east of Los Angeles. Beginning in 1900, Guasti was able to develop a vineyard that ultimately grew to some 5,000 acres and was, inevitably in California, proclaimed "The World's Largest"; the winery he built to receive the tide of grapes from his sea of vines had a capacity of five million gallons.[69]

The decades from the nineties down to Prohibition were not notable for innovation in the wine industry. Its position as a distinctive and favored element in the general economic system of California was well established after several generations of promotion, experiment, legislation, and hard work. Technical work went on quietly at the university, as it had done since 1880, but the pioneering on such basic matters as varietal selection, the identification of the different viticultural regions in the state, and the discovery of winemaking techniques adapted to California conditions had already been well begun. Such work is never finally done, but no remarkable changes were made in the general scheme of things in these years.

The notable change was only in the slow growth of wine production. In 1895, one year after the formation of the CWA, the state of California produced a little less than 18 million gallons of wine. There were great fluctuations in the annual production thereafter—the 31 million gallons of 1898, for example, were followed by a mere 19 million the next year—but overall the graph of production kept moving steadily up. There were 23 million gallons in 1900, 31 million in 1905, and 45 million in 1910. Production thus doubled in a decade, and in a state whose population in 1910 was only a little more than two and a quarter million, winemaking was evidently a matter of great importance. In the early days much, perhaps most, California wine was sweet; and so it would be again, after the repeal of Prohibition and down to 1967, when dry table wine at last edged ahead of the sweet wines. But in these prosperous decades before Prohibition, the wine of California was dry table wine, both red and white. The proportion was two to one in favor of table wine in 1900, and though the share of the sweet wines crept up in following years, it did not overtake table wine; it was 13 million against 18 million in 1905; 18 million against 27 million in 1910.[70]