The Rise and Fall of Anaheim

A bout the time that Haraszthy migrated to Sonoma an other enterprise began in the south of the state that, in its unlikely origins, its rapid prosperity, and its even more rapid demise, presents a number of points of interest. This was the invention and development of the Anaheim colony, now celebrated as the site of Disneyland but originally a well-planned, well-executed agricultural experiment devoted to the production of grapes and wine.[1]

Its remotest origins were in the operations of the firm of Kohler & Frohling. As soon as the two German musicians began to sell their wine successfully, they saw that they needed a larger supply of grapes than Los Angeles yet afforded; they also saw that the empty spaces of Los Angeles County might be quickly and cheaply developed into vineyards. The catch was to find people willing to do the work; the answer was the German population of San Francisco, a population that Kohler and Frohling, of course, already knew and understood. There was a considerable colony there by 1857, all of them drawn by the Gold Rush. Many of them were now both disenchanted with golden prospects and dissatisfied with crude and violent San Francisco as a place in which to raise families and pursue the life of Gemütlichkeit .

The work of forming an agricultural colony out of these San Francisco Germans was assigned to another German, George Hansen (an Austrian, actually), who had served as deputy surveyor to the county of Los Angeles for six years, knew the region well, and had been in consultation with Kohler and Frohling

77

The seal of the Los Angeles Vineyard Society, formed in 1857 by Germans in

San Francisco to grow grapes and make wine in Anaheim (then still a part of

Los Angeles County). They prospered for the next thirty years, until their

vineyards were destroyed by a mysterious disease. (From Mildred McArthur,

Anaheim: "The Mother Colony " [1959])

about the practicability of their plan from the beginning. In February 1857 Hansen held a meeting with the San Francisco Germans at which the plan was unfolded and the Los Angeles Vineyard Society was formed.[2] The scheme was simple. The society would issue fifty shares at $1,400 each (originally the figure was lower, but this was the sum eventually arrived at); with the capital thus raised, the society would buy land, divide it into twenty-acre parcels, of which eight were to be in vineyard, and assign one to each shareholder. But—and this was the distinctive idea of the whole scheme—before anyone moved onto his property, everything was to be put in readiness. By this arrangement, the participants would avoid the rigors of the first pioneering years and—more important—they could remain at their jobs in San Francisco while they earned the money to pay for their shares. This was capitalism on the installment plan. A down payment would secure a share; with the capital thus generated the work could begin; and the shareholder could stay gainfully employed right where he was until he had paid up his share and the new land was ready for him.[3]

The scheme worked quite well. Hansen was made the general manager for the Vineyard Society and set to work scouting for a property to buy in the southland. His first intention, to buy land along the Los Angeles River, did not work out. Under pressure of the impatience of the society's members, he fell back on the knowledge he had acquired as a county surveyor: in 1855 he had surveyed the Rancho San Juan Cajon de Santa Ana, owned by Juan Ontiveros, lying along the Santa Ana River some twenty miles south of Los Angeles. The grapes of the Santa Ana region had a reputation as the "sweetest and best grapes in the state";[4] whether they deserved that or not (and there cannot have been many vines in the Santa Ana Valley then), the important fact was that Ontiveros was willing to sell to the society. In September 1857 Hansen completed the purchase from Ontiveros of a 1,165 acre tract, with water rights providing for an irrigation canal from the river, some six

78

George Hansen, the Austrian surveyor who purchased the Anaheim property,

built the irrigation works, laid out the site, and planted the vines in readiness for

the arrival of the colonists. (Anaheim Public Library)

miles away. Hansen's first order of business then was to lay out the irrigation sys-tem-the gravity flow from northeast to southwest determined the disposition of the Anaheim streets as they exist today—and to arrange the site for occupation.[5] Within two years, working with a motley crew of Indians and Mexican irregular labor, he had done it: the irrigation channels had been dug, the vines—400,000 Mission cuttings[6] mostly from the vineyards of William Wolfskill in Los Angeles—had been planted, and the whole property surrounded by a fence of 40,000 six-foot willow, alder, and sycamore poles, later to grow into a living hedge as a protection against wild animals and range animals alike. The whole expense of two years' labor of preparation was $60,000.[7] Inevitably, Hansen had to encounter

grumblings from his impatient stockholders, but he seems to have done a remarkably capable job of laying the foundations of a successful agricultural community from scratch on land that was nothing but rough, dry, lonely range in every direction. The little house that Hansen built in 1857 as a place to live and from which to direct the operations of his Indians still stands in Anaheim, now a museum called the Mother Colony House.

In September 1859 the first shareholders arrived to claim their twenty-acre homesteads in the colony that now had a name: Annaheim. The name—soon altered from the German Anna to the Spanish Ana —signifies "home on the Santa Ana River"; it had narrowly beaten out the rival name of "Annagau" by vote of the shareholders in 1858.[8] It is a curious circumstance in the history of a successful winemaking colony that most of the Anaheim colonists—there was but one exception—had not only no experience of winemaking but no farming experience at all. They were small tradesmen, craftsmen, and mechanics. They had only their Germanness in common, and so they present a very different case from the earlier German agricultural colonies—Germantown, Pennsylvania; New Harmony, Indiana; and Hermann, Missouri, are instances—so important in the history of wine in this country. The Anaheimers were of diverse origin: they came from Saxony, Hanover, Schleswig-Holstein, Baden, and elsewhere; they were not co-religionists; and, after the colony's land had been bought, laid out, irrigated, planted, and distributed, they ceased to have any further cooperative arrangement.[9] Each shareholder was an individual proprietor, competing with his neighbors just as much as if he still lived in San Francisco, Los Angeles, or Frankfurt. But there was, nevertheless, an intense spirit of community in Anaheim, given the common nationality, the common enterprise of winegrowing, and the common isolation of life on a raw, remote site.

The reality of life in early Anaheim must have been hard, without much margin or amenity. The site was unattractive, a sandy alluvial fan watered by a thin stream flowing through a shallow ditch; it lay, too, in the path of the dessicating Santa Ana wind of winter, booming down off the high desert through the mountain passes to the ocean and leaving a wake of blown sand and jangled nerves behind it. And it would be years before the work of man could do much to ameliorate the scene. A writer in 1863, one of the shareholders, noted that nearly 600 acres—half of the entire tract—still lay vacant, and yet "the welfare of the vineyards requires that this land should be cultivated, for it is now covered with weeds and brush and is the home of innumerable hares, squirrels, and gophers, which eat the vines, young trees, and grapes."[10]

Even from the very earliest years, however, the accounts of the place tend almost invariably to stress the tranquil, harmonious, pastoral simplicity and fruitfulness of the colonists' life. No doubt the idea of a frontier settlement that combined a real community of language and habits of feeling with the poetic labor of winegrowing made this inevitable. And certainly Anaheim was different from the western model of town life. In any case, to conclude from the language of the many

79

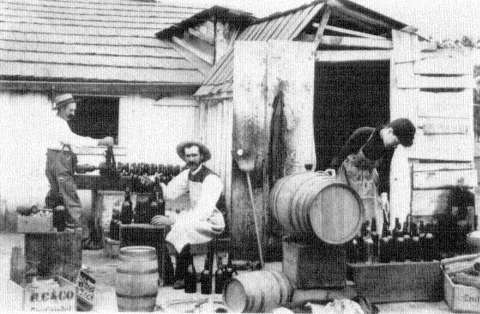

James Bullard, M.D., bottling wine behind his office on Los Angeles Street, Anaheim, c.

1885. Wine was a familiar object throughout Anaheim. (Anaheim Public Library)

newspaper articles generated by curiosity about the Anaheim experiment, all was peaceful and prosperous in the colony: "Their soil is good, their climate, also, their wine is fine, and their tables well supplied" as an envious reporter for the Alta California put it in 1865.[11] Whatever the fantasies about Anaheim, though, the plain fact is that the wine business did succeed, for reasons having perhaps less to do with the quality of the wine or the efficiency of the organization than with the demand for wine on the coast. The wine was made by the various proprietors separately, with the result that Anaheim wine was not a uniform but a highly unpredictable product, at least at first.[12] Later, consolidation and cooperation did come about, but a high level of individualism seems to have persisted to the end.

The wine was not long in acquiring a reputation. The eastern traveller Charles Brace, who did not flatter California wine in general, found Anaheim wine "unusually pleasant and light .... It cannot be stronger than ordinary Rhine wine." He also observed that it was the only wine that could be found throughout the state in 1867: "I found it even in the Sierras, where it was sold at $1.00 a bottle."[13] Much of the crop, too, went to Kohler & Frohling in the early years, as had been the original intention, and their standards certainly helped to establish the reputation of the wine of Anaheim.

There were forty-seven wineries—that is, individual winemaking proprie-

80

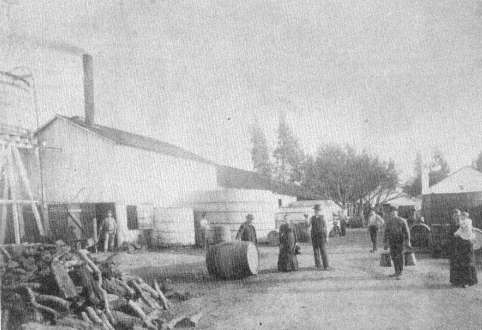

The Dreyfus Winery, Center and East streets, Anaheim, c, 1880. This establishment was

later replaced by a larger winery that never functioned, owing to the death of the vineyards

from the Anaheim disease, (Anaheim Public Library)

tors—in the first decade; two decades later there were fifty, though some of them were by no means small. From a token 2,000 gallons in 1860, the year of the first vintage, production had reached 300,000 gallons in 1864.[14] Twenty years later, at the moment when the Anaheim wine industry was just about to come to its sudden and unforeseen end, production had reached its highest point. Some 1,250,000 gallons of wine were produced by the town in that year, along with 100,000 gallons of Anaheim brandy.[15] In the roster of winery names, German still predominated—Kroeger, Koenig, Langenberger, Zeyn, Lorenz, Reiser, Dreyfus, Korn, Werder—though there were also by that time a Browning Brothers and a Golden Belt Wine Company. Anaheim had also attracted two most unlikely characters, the famous Helena Modjeska, the Polish actress, and a young Polish gentleman later to be quite as famous as the Modjeska, Henryk Sienkiewicz, the author of Quo Vadis . They had come to join a Utopian colony in Anaheim that had only a very brief life, and neither stayed long. Modjeska later bought a summer home in the Santa Ana mountains not far from Anaheim, and Sienkiewicz makes a few references to Anaheim in some of his American sketches, but neither was much taken by the place.[16]

The king of Anaheim winemakers was unquestionably Benjamin Dreyfus, a Bavarian Jew.[17] He was not a member of the San Francisco group that formed the

81

The letterhead of B. Dreyfus & Co., in the year that the vines were being

devastated. Note that the letter is in German. (Anaheim Public Library)

Los Angeles Vineyard Society, but he was a resident of the Anaheim site even before the first shareholders arrived. Dreyfus had opened a store there in 1858 in anticipation of the new community, had welcomed the first settlers to the place, and soon showed that he had gifts as a salesman that were just what was needed by the growers. In 1863 Dreyfus went to San Francisco to manage the depot of the Anaheim Wine Growers' Association (there, incidentally, he made Kosher wine in 1864—perhaps a first for California).[18] Shortly thereafter he opened the firm of B. Dreyfus and Company in New York and San Francisco, through which he sold Anaheim wines. Among his clients was his own winery in Anaheim, supposed at that time to be the largest in the state and using the produce of some 235 acres by 1876.[19] Dreyfus eventually owned properties in Cucamonga, San Gabriel, and the Napa Valley as well as in Anaheim. By the end of the sixties, through Dreyfus and other agents, the city of New York had a wide variety of Anaheim wines available to it: Anaheim hock, claret, port, angelica, sherry, muscatel, sparkling angelica, and brandy are all listed in a promotional pamphlet of the time.[20] The array is striking evidence that the California practice of producing a whole "line" of wine types from one site and from a limited number of grape varieties is no new thing)[21] Dreyfus is said to have made genuine riesling and zinfandel, but the Mission was always the staple grape of Anaheim so long as grapes grew there.[22]

As in the design of a well-made tragic drama, the high point and the collapse of Anaheim winegrowing occurred at the same moment. That was in 1883, when the fifty wineries of Anaheim were yielding their more than a million gallons and when the acreage of vines in the Santa Ana Valley was estimated at 10,000, including substantial plantings for raisins and for table use. In the growing season that year the vineyard workers noticed a new disease among the Mission vines. The leaves looked scalded, in a pattern that moved in waves from the outer edge inwards; the fruit withered without ripening, or, sometimes, it colored prematurely, then turned soft before withering. When a year had passed and the next season had begun, the vines were observed to be late in starting their new growth; when the shoots did appear, they grew slowly and irregularly; then the scalding of the leaves reappeared, the shoots began to die back, and the fruit withered. Without the support of healthy leaves, the root system, too, declined, and in no long time the vine was dead.[23] No one knew what the disease might be, and so no one knew what to do. It seemed to have no relation to soils, or to methods of cultivation, and it was not evidently the work of insects. Not all varieties were equally afflicted, but the disease particularly devastated the Mission, far and away the most extensively planted variety in the vineyards of Anaheim. By 1885, according to one doubtless exaggerated report, half the vines of Anaheim were gone; in the next year, "there was not a vine to be seen."[24] In fact, some vineyards persisted long after this, but the assertion, made by a longtime resident, expresses the sense of sudden, unsparing destruction that the disease created in the Anaheimers as they looked over their blighted vineyards. The official government report estimated the loss to the disease at Anaheim and elsewhere in the Los Angeles region at $10,000,000.[25]

The disease was not confined to Anaheim; much of the San Gabriel Valley and the Los Angeles basin east through Pomona to Riverside and San Bernardino was seriously affected too; the flourishing trade of the San Gabriel region never fully recovered. Anaheim, and the neighboring vineyards of the Santa Ana Valley at Orange and Santa Ana, planted after the success of the Anaheim experiment, were the hardest hit in the midst of the general affliction. The Anaheimers appealed to the state university for expert opinion, and the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners hired a botanist to study the problem. But the disease baffled all inquiry, and meantime its effects were rapid and sure.

In response to repeated appeals, the U.S. Department of Agriculture belatedly sent an investigator to the Santa Ana Valley in 1887; he was puzzled by all that he saw, but reported hopefully that the trouble would "probably disappear as quietly and mysteriously as it came."[26] In 1891 the department sent another investigator, Newton Pierce, whose careful investigation showed that the disease was none of those currently known and that no remedies existed for it. Pierce's reward for his careful and thorough studies was to have the disease named after him. By the time his report was completed, in 1891, the region of Anaheim was reduced to fourteen acres of vines and its identity as a center of winegrowing utterly annihilated.[27] The fate of the bold new winery building that Benjamin Dreyfus, the Anaheim wine

82

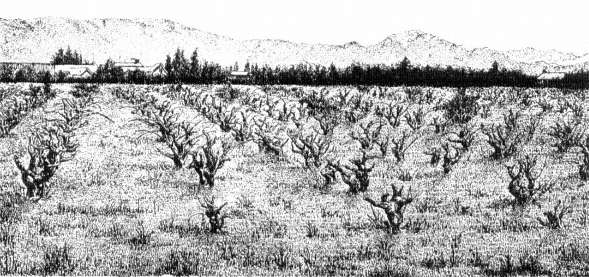

A vineyard of Mission grapes in LOS Angeles County killed by the Anaheim disease. The vines,

planted more than twenty-five years earlier, were dead by 1890, when the picture was made. Mission

vines were peculiarly susceptible to the disease, but all were vulnerable. (From Newton B. Pierce,

The California Vine Disease [1892])

king, had erected in 1884 is symbolic. This was an imposing stone building, far larger than anything else of the kind in the area, but when it was completed and ready to receive a vintage, there was no vintage to receive. The building thereafter passed through various humiliating roles as a warehouse, as a factory for chicken-feeding equipment, even as a winter quarters for a circus. When the freeway went through in the 1960s, part of the building was lopped off by the right of way, it was at last put out of its long agony by demolition in i973.[28]

Anaheim recovered from the disease by turning to the new crops that were just at that time rapidly developing in southern California, especially oranges and walnuts. The Germans of Anaheim had long since set up breweries, and these, of course, were unaffected by the grape disease. So the settlement, which became otherwise indistinguishable from its neighboring communities in making its living from tree crops, still managed to enjoy some notoriety for its beer, its beer gardens, and its beer drinkers. These gave a welcome scandal to their Orange County neighbors, who would otherwise have had little diversion in their rural lives.

What was the Anaheim disease? The plant pathologists have not yet arrived at satisfying answers, but they have continued to study the question because the disease still exists and still threatens California vineyards. In quite recent years, it has been established that the carrier of the disease is a leafhopper, and that the pathogen, as Pierce suspected, but could not prove, is a bacterium. It is also known that the incidence of the disease varies with the populations of its leafhopper carrier, so

that wet years favor it, and sites having abundant weedy and bushy growth surrounding them are vulnerable—both circumstances mean more leafhoppers and so more danger of infection. So far, the only known effective treatment is to pull the infected vines and to start with others, hoping to keep them free of infection.[29] The University of California at Davis is carrying on work to develop a vine specifically resistant to Pierce's Disease by modern means of genetic manipulation, but success has yet to be achieved.[30]

One other thing is known: that the home of the disease in this country (to which it seems so far confined) is in the states bordering on the Gulf of Mexico. The native grapes of that region are the only ones to show any power of resistance to it, and the presence of the disease there doubtless helps to explain why the repeated trials of grape growing in that region met with such poor success. There are abundant other reasons for that result, of course, but the potent destructiveness of Pierce's Disease was certainly a factor in the deaths of any vines brought in from the outside.[31]