10

The Haraszthy Legend

The United States, though rather an old country now as standards of national identity go, still feels itself to be young and therefore takes an anxious interest in its founders and fathers. The California wine industry has had, according to the stories repeated over and over in the press at every level since the late nineteenth century, a "father" named Agoston Haraszthy.[1] In 1946 the title was officially sanctioned by the state of California at ceremonies dedicating a memorial in Sonoma to Haraszthy as the "Father of California Viticulture": one may still contemplate the bronze assertion on the north side of the old plaza in Sonoma. The same formula identifies a vine planted in Haraszthy's memory in 1961 by Governor Edmund Brown in Capitol Park, Sacramento.

How good is Haraszthy's claim? Is it only the result of effective publicity? Does it mean something solid? Or is it just a mistake? On a simple documentary level the answer is clear. As the preceding chapter has shown at some length, viticulture and winemaking in California were thoroughly established long before Haraszthy made his way to the state in 1849. By that time there was a history of nearly three-quarters of a century of practical winegrowing, and a strong effort towards improving the selection of grape varieties was already well under way. But if one tries to answer the question in a more critical way, the case grows a little complicated. "Father," after all, is not a very useful metaphor: a literal father must have an exclusive claim, but a man who pioneers in a decisive way may share credit with a good many predecessors. The best thing to do, then, seems to be to tell Haraszthy's story as well as it can be reconstructed (many important questions have never been answered), and to let that stand as an argument for or against the alleged paternity connected with his name.

74

Agoston Haraszthy (1812-69), the Hungarian who developed the Buena

Vista Vineyard in the late 1850s, He has since been given credit as a

pioneer of California winegrowing out of all proportion to his actual

contributions. (Wine Institute)

Both the beginning of Haraszthy's life in the old Austro-Hungarian empire and its ending in the forests of Nicaragua are quite indistinct so far as the record goes. What were his activities before he came to the United States? And was he, at the end, devoured by an alligator? No one seems to know. But between those two points, the busy, confident, multifarious, and striking activities of Haraszthy left a strong impression that remains clear enough today.[2] The son of a landed proprietor, Agoston Haraszthy was born in 1812. at Futak, on the east bank of the Danube at the end of its long run from north to south across the great Hungarian plain. The place was then in southern Hungary but is now a part of Yugoslavia. Young Haraszthy is said to have studied law, to have been a member of Empero-

Ferdinand's bodyguard, and to have served as private secretary to Archduke Joseph, palatine of Hungary. At some point—indistinct like all of the details of the early years—Haraszthy retired to his estates and pursued the life of an enlightened agriculturist; winegrowing and silk culture were among his interests. In this period, Haraszthy served in the Hungarian Diet; he also married a Polish lady, by whom he had six children: four sons named after the heroes of Hungarian history—Geza, Attila, Arpad, and Bela—and two daughters.

In 1840, together with a cousin, a boy of eighteen, Haraszthy left Hungary for the United States; the reason, according to Haraszthy's statements afterwards, was political. The failure of Louis Kossuth's liberal movement, with which he was in some way associated (indistinct again), is supposed to have forced him to flee[3] Haraszthy has, in consequence, traditionally been represented as a hero of the liberal cause in Europe. But the claim is not clearly made out, to say the least. For one thing, Kossuth had just been released from jail when Haraszthy first left Hungary. For another, Haraszthy's cousin and travelling companion on that first visit to the United States later affirmed that he and Haraszthy had left Hungary "for no reason, except to wander."[4] Whatever the truth of that matter, Haraszthy was able to return to Hungary in 1842 to sell his estate there and to bring his whole family, father and mother included, back to the United States. If he was a political exile, he was evidently under no very severe persecution.[5]

Haraszthy had, on his first visit to America, bought land on the prairie bordering the Wisconsin River where the town of Sauk City now stands. From 1842, when he settled there with his family, until 1848, when he left for California, Haraszthy was the prince of this Wisconsin property. With a partner he set about developing a town—at one point it was called Haraszthy—and he took a hand in all sorts of pioneer enterprises: a brickyard, a sawmill, a general store, a hotel. He sold lots; he operated a ferry across the Wisconsin River and a steamboat on it; he held a contract for supplying corn to the soldiers at Fort Winnebago, and raised large numbers of pigs and sheep; he planted the state's first hop yard (prophetic of Wisconsin beer). He also published Travels in America , a two-volume account of his American impressions, in Hungary in 1844, partly in order to stimulate immigration to his Wisconsin lands (the publication is further evidence that Haraszthy was not a political exile). Despite the pressure of these affairs, Haraszthy seems to have spent much of his time as an enthusiastic outdoorsman, riding and hunting with a flamboyance that amazed the simple Wisconsin settlers: one anecdote tells of his killing a wolf with his bare hands.[6] He was tall, dark, fiercely mustached, and given to wearing aristocratic boots and a green silk shirt with a red sash. It is no wonder that the natives always called him "Count," though he was not a member of the Austro-Hungarian nobility.

From the point of view of his later work in California, Haraszthy's most interesting project in Wisconsin was his attempt to grow wine there, high up above the forty-third parallel, in the middle of a continent. He set out vines in 1847 and in 1848, and built a forty-foot cellar to receive the fruit of his vines. But winter frosts

killed the vines and there is no evidence that Haraszthy succeeded in producing a Wisconsin wine before he left the state.[7]

At the end of 1848 Haraszthy turned his back on all this—probably he was dissatisfied with the financial results of all his speculations—and prepared to travel overland to California with his family. They left St. Joseph via the Santa Fe Trail in the spring of 1849, ahead of the main wave of forty-niners and apparently without any intention of literal gold-seeking. The news of gold in California had reached the East at about the time that Haraszthy left the village he had founded in Wisconsin, but instead of heading for the Mother Lode, Haraszthy made his way to the unprepossessing hamlet of San Diego, hundreds of miles to the south. There he was at once energetically busy in his old omnicompetent way. He and his sons briefly experimented with a plan to take over the derelict mission gardens at San Luis Rey, but soon returned to San Diego, where Haraszthy and others had established a market garden in Mission Valley; there, in March 1850, Haraszthy began to plant the first of his Californian vineyards, with cuttings taken from the Mission San Luis Rey's surviving vines. Haraszthy is also said to have ordered roots and cuttings of vinifera vines from Europe and planted them in 1851, the first of the many importations that he was to bring into the state. The evidence for this, however, is not reliable.[8] Haraszthy diversified his time in San Diego by Indian fighting, land speculation, and politics: he was elected the county's first sheriff in 1851, and city marshal in the same year, when he also built the town's new jail on a speculative contract (the jail proved incapable of holding prisoners). Haraszthy's brief episode in San Diego came to an end late in 1851, when he was elected state assemblyman for San Diego County and went off to his legislative duties far to the north in Sacramento. He never returned to live in San Diego, and his vineyard there was abandoned.

Haraszthy must have had his mind on growing things as well as on making laws when he left the south of the state for the north; within two months after the legislature had convened in Sacramento he had bought an extensive property near Mission Dolores, south of the city of San Francisco as it then was. At this place, which he called "Los Flores," he began to develop a nursery, including grapevines. But this was no better a place to grow grapes then than it had been in mission days, when the Franciscans found that they could not succeed with grapes there. Haraszthy sold part of the property in 1853 and began buying land farther south on the peninsula in the hills near San Mateo (the land now lies under the waters of the Crystal Springs Lakes reservoir); by 1854 he had planted thirty acres of grapes there.[9]

He had also begun to operate as an assayer and refiner of gold in San Francisco in partnership with two fellow Hungarians. In 1855 he was made official smelter and refiner at the branch mint in San Francisco, and, despite his public appointment, joined in a private gold and silver refinery as well. Haraszthy came to serious grief in this activity, for in 1857 a grand jury brought in a charge against him for the "embezzlement" of $150,000, the value of the gold for which he was unable to

account after a tally of the mint's gold had been made. Haraszthy was forced to mortgage or sell the larger part of his properties and to hand over his assets to the government in pledge, while a complicated inquiry and trial took place. What was finally determined was that, under the strain of extraordinary operation night and day, the furnaces of the mint had allowed gold to escape up the chimneys in quantities beyond the officially permitted measure of waste. Haraszthy—who by this time had made enemies as well as friends—was cleared, but not until 1861.[10] In the meantime, he had begun the work for which he is now remembered in California.

Haraszthy had already learned that the cool wet fogs of the peninsula made his Crystal Springs property unsuitable for successful grape growing, and so he began to cast about for another place—his fourth in California and fifth in the United States, if we count the Wisconsin venture—where grapes might do well. He found it across the bay to the north, ouside the town of Sonoma, where Vallejo, who had already been growing grapes for a generation, had since the Gold Rush built a new house, laid out a larger vineyard, and begun taking prizes for his wines at the newly founded state fair. On a property nearby were some sixteen acres of vines called the Sonoma Vineyard, said to have been planted by an Indian as early as 1832.[11] The wine from it was good enough to convince Haraszthy that he could do even better there. Accordingly, in 1856, in the very midst of his troubles with the Mint, Haraszthy bought about 560 acres of Sonoma property, lying northeast of the town, including the Sonoma Vineyard, and extending up the slopes of the Mayacamas Mountains. Work began at once in transferring vines from the San Mateo vineyards to the new property in Sonoma; Haraszthy himself moved there in May 1857 and made it his home until he left California some ten years later.

The astonishing confidence and energy of the man is abundantly illustrated in his operations now. He was now always known as the Colonel, for "Count" would not have sat well on the freely elected member of a representative assembly, such as Haraszthy had been in California: the claim to "Colonel" presumably was based on Haraszthy's service in the imperial bodyguard—or perhaps it was based on nothing but personal style. In any case, the Count-Colonel christened his new estate Buena Vista, and at once proceeded to transform it. Within a year he had 14,000 imported vines growing and another 12,000 in his nursery, the whole consisting of some 165 varieties.[12] He also planted extensively for other landowners, among them such names later famous in California winemaking as Krug, Gundlach, and Bundschu: by the end of 1857 Haraszthy and others had more than tripled the total grape acreage of Sonoma County.[13]

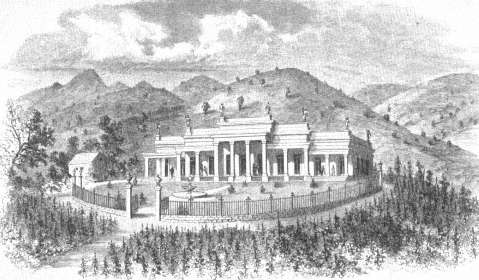

In preparation for the abundant harvests that were soon to come, he set his Chinese coolies to digging tunnels back into the hillside to serve as wine cellars: one was 13 feet wide and 100 feet long; the other, 20 feet wide, was driven back 240 feet into the hill.[14] To crown his vineyards he built a large white villa in Pompeian style, boasting a pillared porch and a parapet surmounted by statues of classical figures (so at any rate the pictures show it). From this vantage he could look south and west over the vines and grain fields of the valley all the way to San Pablo

75

The villa in "Pompeian" style built by Agoston Haraszthy on his Buena Vista ranch property,

Sonoma County, This was the final touch to Haraszthy's flamboyant development of Buena

Vista. No trace of the house remains today. (From Haraszthy. Grape Culture. Wines. and

Wine-Making [1862]; Huntington Library)

Bay. When Haraszthy was entertained at Schloss Johannisberg in 1861, he politely admired the splendid view that Prince Metternich, the owner, enjoyed of the Rhine, but he thought to himself that his own Buena Vista did quite as well: "The Prince may boast of the view from his palace, as I can from my ranch in Sonoma; or, rather, I may boast of having scenery equal to that of the Prince Metternich. It is true that I have no River Rhine, but in its place there lies the St. Pablo Bay."[15]

The rapidity with which Haraszthy established himself once he had settled in Sonoma may be documented by various details: he set out 300 acres of vineyard between 1858 and 1862, and in 1859 he was able to claim first prize for the best exhibit of wines at the state fair, "with reference to the number of varieties, vintages, and quality"; among the items of his exhibit were a tokay and a wine obscurely called "Menise" or "Monise" (the name is spelled both ways in the record).[16] Two of Haraszthy's sons, Geza and Attila, soon had vineyards of their own in Sonoma, and Arpad had been sent to France in order to study, among other things, the manufacture of champagne at Epernay. Haraszthy continued to import grape varieties from Europe to augment his collection: the 165 varieties in it early in 1858 had grown to 280 later in that year. By the beginning of the 1860s he claimed to have the largest vineyard in the state, or, sometimes, "the largest vineyard in the world."[17] For a man who had just been compelled to resign his official appointment, to mortgage his properties, and to face a criminal trial, all of this was evidence, not merely of a remarkable insouciance, but of a powerful determination

to do just what he chose to do. He must have outraged his enemies, and he must have had great pleasure in so doing.

The remarkable improvements that Haraszthy had made at Buena Vista attracted attention at once; in the first year of his settlement there, the gentlemen of the California State Agricultural Society asked him to write a treatise on the science and mystery of winegrowing in the state. The difficulty of such a task was nothing to Haraszthy, who, by February 1858 had dashed off a "Report on Grapes and Wine of California"; it may be regarded as the first native Californian treatise on the subject, and though, like all first words, it could hardly have the authority of a last word, California was lucky to have anything so intelligent. The "Report" was published in the Transactions of the society for 1858, and was, as well, separately reprinted for extensive distribution throughout the state.[18] There is nothing particularly notable or original in this essay, unless perhaps we except Haraszthy's instructions for making a tokay wine; these called for raisined grapes pressed by their own weight, the classic method of Hungarian tokay Eszencia .[19] Perhaps that was the method that produced Haraszthy's prize-winning tokay of 1859; if so, it was not likely to be imitated widely in California.

On the matter of the choice of varieties, Haraszthy agreed with what many others were already saying: the quality of California wine, he wrote, would never be what it might be so long as the Mission grape was the standard. He also thought that California should study the art of blending:

To illustrate this more to every man's mind, I will compare the wine-making with the cooking of a vegetable soup. You can make from turnips a vegetable soup, but it will be a poor one; but add to it also potatoes, carrots, onions, cabbage, etc., and you will have a fine soup, delicately flavored. So it will be with your wine; one kind of grapes has but one eminent quality in taste or aroma, but put a judicious assortment of various flavored grapes in your crushing-machine, and the different aromas will be blended together and will make a far superior wine to that manufactured from a single sort, however good that one kind may be.[20]

Haraszthy's prosperity crested in 1861. In that year production at Buena Vista was large enough to allow him to open a branch office in San Francisco.[21] Even better, the long court case against him growing out of his work at the Mint was decided in his favor in March, and the property that he had had to place in trust was then returned to him:[22] one must remember that all of Haraszthy's enthusiastic labor at Buena Vista up to this point had been carried out under the cloud of his protracted trial. In April, very shortly after his release from the Mint charges, Haraszthy was appointed by Governor John Downey one of the state commissioners to report "upon the Ways and Means best adapted to promote the Improvement and Growth of the Grapevine in California." The commission, created by joint resolution of the assembly upon the urging of the California State Agricultural Society, had three members: one was to report on California; one was assigned to South America; and one—Haraszthy—to Europe.[23] A month later he

was on his way, at the beginning of a trip whose consequences, though not easy to specify or to assess, have long been regarded as having profoundly affected wine-making in this country, so profoundly indeed that in the popular version the whole history of winemaking is divided into two parts, before and after Haraszthy's European tour. Let us see what that was.

Armed with his commission from governor and assembly, and accompanied by his wife and by their daughter Ida, Haraszthy set out at his own expense, for the commissioners were not to be paid for their work. On reaching the East Coast, he first stopped at Washington to get a circular letter of introduction to the American consular corps from Secretary William Henry Seward. He then went to New York, arranged there with the publishers Harper & Brothers to produce a book on his mission, and, on 13 July, sailed for Europe. The purpose of his trip, according to the terms of his commission, was simply to make observations upon European practices in viticulture and winemaking and to report on these to the state. But in his own mind Haraszthy seems to have had the collection of grape varieties as his first and most important business. At any rate, he talked in that way before his departure, and he spent a good deal of energy that way during his tour.

It was not a very extensive tour, compared to the possibilities that might easily be imagined. Making his first headquarters at Paris, he visited Dijon and several great Burgundian sites—Gevrey, Chambertin, Clos Vougeot. Then he moved on into Germany to visit such wine towns and noble estates as Hochheim, Steinberg, Kloster Eberbach, and Schloss Johannisberg. In Germany he made his first purchase of vines, a hundred varieties from a nursery in Wiesloch. Haraszthy now went into Italy, to Turin and to Asti, where he bought a second collection of vines, including the Nebbiolo, the preeminent grape of the region. He had originally thought of taking in Rome and Naples, but he now abandoned the idea, since, as he explained, he had friends through whom he could order cuttings there. At the same time he abandoned any thought of travelling farther east—not even to his native Hungary. "It is true that my original intention was to visit Greece and Egypt," he wrote in the published account of his travels; but, he added as a sufficient reason, he learned that the plague had broken out in Syria, so that "I, of course, decided not to go."[24]

Instead, he turned back to the west, travelling to Bordeaux via Marseilles and Cette—a town then infamous for its trade in adulterating wines and the source, Haraszthy asserts, of most of the wines that Americans drank as Château Margaux, Château Lafite, and Chambertin. For some reason, the Bordeaux region did not especially interest Haraszthy. He paid brief visits to Château Margaux and to Château Rauzan (then still undivided) but did not, according to his report, pursue his inquiries any further. On the nineteenth of September he set out for Spain, where the conditions of travel were much the most difficult of his entire tour. Railroads were being built, but the system was not linked up yet, and travellers had to fill in the gaps by taking passage in huge diligences pulled over the breakneck mountain roads by teams of mules. After four days of such travel Haraszthy reached

Madrid, and then pushed on to Malaga. The wines of Spain he did not care for, since he found that they were all invariably fortified. He bought vines at Malaga, however, and again at Alicante, where he had gone from Malaga by steamer. That marked the end of Haraszthy's inspection of European viticulture, for from Alicante he returned to Paris, and shortly thereafter set out on a stormy crossing of the Atlantic to New York. By the fifth of December he was back in California, having completed his travels from San Francisco to the Mediterranean and back in just six months.

Haraszthy's first business was to make his report to the state legislature, which he did, briefly, under date of January 1862. In this he reaffirmed his belief that California had more natural advantages as a wine region than any European district; he also urged the creation of a state agricultural experiment station, state support of plant exploration, and the appointment of a state agency to handle the commerce of wine in California in order to eliminate frauds.[25] The book that Haraszthy had contracted for on his way to Europe followed soon after as Grape Culture, Wines and Wine-Making, with Notes upon Agriculture and Horticulture , published by Harpers in New York. This was a very hasty production, and, for that reason, very disappointing: though it touches on a number of matters incidentally, it quite fails to give a clear picture of Haraszthy at work on his mission. He does not tell us what questions he had to ask, or how he went about getting them answered, nor has he much to say about the wines he encountered, or the problems faced by European wine-growers—just the things, one would suppose, that would occupy him most. He gives instead a sort of journal narrative of his travels, noting down as many miscellaneous items about architecture, topography, general agriculture, and the like as about the vines and wines of those European parts that he succeeded in visiting. Many another traveller might have done as much—and have done it better.

The narrative occupies a good deal less than half of the volume; the rest is bulked out by a melange of pamphlets and treatises picked up in Europe—for example, Professor Johann Karl Leuchs's Wines and Their Varieties ; Dr. Ludwig Gall's Improvements in Wine-Making ; and even The Sorgho and the Impee , an American pamphlet on those newly introduced crops. Haraszthy also included his treatise on wines and vines in California written in 1858 for the state agricultural society, now slightly modified in the light of his subsequent observations on pruning practices and the spacing of plantings. He adds the interesting information that his Buena Vista vineyard now extended over 400 acres and was, he thought, "the largest in the United States."[26] And that is all that there is to the book. It may rightfully claim to be the first book by a California winemaker to be given national circulation, but it has only very incidental remarks to make about California, and then mostly about Haraszthy's affairs, and pitifully little about European practices. The writers-and they are many—who refer to it as a monument in the literature of American winemaking have not, perhaps, looked at it very critically, or have not been able to put it in an adequate historical context.

Haraszthy's Buena Vista vineyards, already the largest in the country, were

76

Title page of Agoston Haraszthy's record of his European tour in the interest of the

California winegrowers. Though largely about European vineyards, its last chapter

is devoted to California. The first discussion in book form of California as a winegrowing

region, it inaugurated a still-vigorous tradition of unrestrained boasting: "No European

locality can equal within two hundred per cent. [California's] productiveness." (Huntington Library)

soon to be even larger, for the vines that he had amassed in Europe were on their way to California—100,000 of them. Haraszthy first reported that his collection included 1,400 varieties[27] —an unreal number—but even after inspection and comparison had reduced this figure, he still had some 300 varieties in his newly imported collection. On the arrival of the vines in late January 1862, Haraszthy reported to the governor that he had prepared the vines for propagation, and that there would be "300,000 rooted vines ready for distribution next fall."[28]

Though Haraszthy wrote as though he expected the state to take responsibility for the distribution of his vines and pay his expenses, he had not been authorized to buy vines or to incur any expenses of any description whatever to be charged to the state. The terms of his commission instructed him only to observe European practices, not to buy large quantities of nursery stock for a state already abounding in vines of every description. Haraszthy knew, of course, that this was the case, just as he knew that the commissioners were not to be paid: the resolution of the assembly authorizing the commission contained this explicit proviso: "Such commissioners who may accept the office shall not ask, or receive, any pay or other compensation for the performance of the duties of their offices." Nevertheless, Haraszthy did ask for compensation—he estimated his expenses at $12,000—and a bill to indemnify him was introduced in the state senate. The senate committee appointed to report on it recommended against it in April 1862, and the bill was stifled.[29]

This has for many years been described as an act of gross injustice and ingratitude to Haraszthy, who has been made to appear a martyr to political faction or to some even worse villainy. The tradition that Haraszthy was cheated is by now so well established in California that it has almost mythological status. Yet the facts, so far as they can be known now, tell a very different story. Haraszthy knew from the outset that he was not going to be paid, just as he knew that he had no official charge to buy vines for importation. Why then did he buy them? Evidently for the simple purpose of making money. Before he left for Europe he was advertising a scheme for buying vines and other plants in Europe for subscribers: $25 would buy twenty-five varieties of vine, $50, fifty varieties, and so on up to $500, in return for which the subscriber would receive "two cuttings of every variety of grape now in cultivation in the civilized world."[30] The coolness of that last offer tells us a great deal about the man. When Haraszthy returned from his European visit and announced that he was having a large quantity of vines sent after him, the Los Angeles Star wrote simply that Haraszthy "will make a handsome profit from their sale."[31] Probably he did. There is nothing wrong with that. But it was an astonishing piece of effrontery to pretend that he was owed compensation for his expenses, and to pretend to be aggrieved when it was denied.

What vines does California owe to Haraszthy's importations? Since it has long been taken as uncontested truth that Haraszthy greatly improved the standards of California through the introduction of superior varieties, it would be interesting to know what some, at least, of those varieties were. There is no clear, positive

evidence on the matter. Even at the time, there was much confusion as to what varieties Haraszthy had obtained: many of them had been collected not directly by Haraszthy but by the agency of friends and by members of the consular service; the chances of mislabelling in the process of shipping, transshipping, and planting were considerable; and there was no guarantee of authenticity at the source. Haraszthy himself, as we have seen, thought at first that he had some 1,400 varieties, suggesting that many vines of the same variety had been given different names.

After the vines had arrived and been put into his keeping in Sonoma, and after his bold attack on the public purse to pay for them had failed, Haraszthy prepared a catalogue of the varieties that he had for sale. This included both his recent importations and those that he had earlier imported into California, or had, perhaps, obtained from other California nurserymen. It makes a sufficiently exotic and interesting list, a total of 492 varieties.[32] Hungarian kinds figure notably: Bakator (both white and red), Boros, Csaszar szolo, Dinka, Furmint, Jajos, and Kadarka are among the many names. None of these is now commercially grown in California, if any of them ever was. Other striking exotics are a red Corinthe from the Crimea, the Kishmish from Smyrna, the Marocain Noir from Morocco, the Tautovina of Carinthia, and Torok Malozsla from Turkey. There are many, many more unfamiliar varietal names on the list, most of them probably familiar varieties masquerading under unfamiliar local names, but some of them at any rate varieties that did not "take" in California—the German Affenthaler, for example, and the French Calytor.

Of the varieties now either most prominent or most highly regarded in California, many are represented on the list: Cabernet Sauvignon, Carignane, Pinot Noir, Sauvignon Blanc, Semillon, Riesling, Sylvaner, Gewürztraminer, and perhaps the Chenin Blanc, if that is what is meant by the item identified as "Pineau blanc." Among the varieties one misses are the Chardonnay, the Grenache, and the Syrah. It is, perhaps, safe to say that many of the varieties named in Haraszthy's catalogue were first imported into California by Haraszthy, but that among them were very few, if any, of the varieties that have any importance now. Since the importation of superior varieties of vinifera into California goes back to the early 1830s, Haraszthy had long been anticipated with respect to the most highly regarded varieties.

By far the most sensational omission in Haraszthy's catalogue of his imported vines is the variety called Zinfandel. Haraszthy's association with this grape, almost the trademark variety of California winemaking, is just as hallowed a part of his legend as his claim to be the "father" of California winemaking. The received account of the connection goes like this. After Haraszthy had left San Diego and had bought his Las Flores property south of San Francisco, he received a shipment of vines from Europe, including the Zinfandel, a variety from his native Hungary. He planted his Zinfandel, the first ever known in California, in the spring of 1852. When he moved from Las Flores to Crystal Springs, and then from Crystal Springs to Sonoma, the Zinfandel went with him, and there, in Sonoma in 1862, ten

years after its importation into the state, Haraszthy produced California's first zinfandel wine.[33]

Such is the story, but against it there is overwhelming evidence, both positive and negative. On the negative side, why is there no mention of the variety in Haraszthy's catalogue of 1862? Two years later, in an article that Haraszthy wrote for a national audience in Harper's , an article of unashamed advertising for his Buena Vista property and its wines, there is still no mention of Zinfandel, though every other possible boast and claim that he can make is duly made.[34] On the positive side there is indisputable evidence that the Zinfandel was known in California before Haraszthy came to the state. Even more to the point, the Zinfandel was a familiar variety on the East Coast when California was still a Mexican province. The Zinfandel (called "Zinfindal") was exhibited at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in 1834 and regularly thereafter; it became a favorite among the fashionable amateur gardeners who could afford to grow grapes under glass in eastern American cities. It is described by Andrew Downing in his Fruits and Fruit Trees of America in 1845, and is frequently mentioned in the agricultural press of the 1840s and 1850s. It may even have been known to William Prince earlier than this, for in his catalogue of varieties published in 1830 Prince includes a variety he calls the "Black Zinfardel of Hungary" among those propagated and for sale at his Linnaean Garden. Whether Prince's Zinfardel is merely a typographical error for Zinfandel or a wholly different variety no one can say now, but the contemporary descriptions of the East Coast's "Zinfindal" show that it is the grape called Zinfandel in California.[35]

The earliest published record of the variety in California is in 1858, when the Sacramento nurseryman A.P. Smith exhibited "Zeinfindall" at the state fair.[36] There is no proof for the supposition, but it seems simplest and likeliest to think that Smith got his "Zeinfindall" from eastern American sources of supply, perhaps as early as 1855. Many years later the San Jose grape grower and nurseryman Antoine Delmas claimed that he had imported the Zinfandel from France to California in 1852, but under the name of Black St. Peters.[37] If so, he would have to be awarded the claim of introducing the variety to the state; we do not have evidence to settle the question. But we do know that the grape was beginning to attract favorable notice before the end of the 1850s: examples were exhibited again at the state fair in 1859, and more than one grower was making wine from it by 1860. During the sixties it attracted more and more attention as the most promising among the many varieties that were competing to replace the Mission, and by the end of the 1870s it was established as the first choice for California's vineyards.

The presence of Zinfandel in eastern America in the 1830s and its importation into California before the end of the 1850s are beyond doubt; the European origin of the variety, however, has not yet been determined, though there is, of course, no doubt that it is wholly vinifera; the most promising claim that has yet been put forward is that it is identical with a grape known in Italy as the Primitivo di Gioia.[38] The mystery we have to do with here, though, is not that of the Zinfandel's Euro-

pean identity, but that of its association with Haraszthy: how did it happen that Agoston Haraszthy was identified as the man who introduced the Zinfandel to California?

The first statement to this effect that I know of was made in 1879 by the San Gabriel winegrower L.J. Rose, who wrote in the Transactions of the California State Agricultural Society of that year that the Zinfandel was "introduced by the late Colonel Haraszthy from Hungary."[39] Rose gives no authority for the statement, but the probability is that he heard it from Haraszthy's son Arpad, who was certainly the most zealous proponent of the claim. Arpad's friend and colleague on the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners, Charles Wetmore, was probably echoing the same source when he wrote in 1880 of "the princely gift to this State made by Col. Agoston Haraszthy in 1860 [i.e., 1862], who brought us hundreds of varieties of valuable grapes from Europe, including our now famous Zinfandel."[40] Later, Wetmore recognized that he had been misinformed; in 1884 he wrote that the Zinfandel "was in this State long before Colonel Haraszthy visited Europe as a State Viticultural Commissioner."[41] There were others who publicly denied the invented Haraszthy claim, but they did not succeed in persuading the public. For one reason or another, the notion that Haraszthy brought the Zinfandel to California has persisted, and now it seems to be so firmly fixed that no amount of historical bulldozing can dislodge it. Still, it is not true.

Even opportunists like Haraszthy, who care nothing for the obstacles and difficulties that other men see all too clearly, may at last find themselves overextended. By 1863 that was the case with him. He was immediately out of pocket for his European tour and the large purchases of vines he had made. The development of Buena Vista into the largest of American vineyards was expensive; the cost of establishing a vineyard then was estimated at $50 an acre, not counting the cost of the land, and though this seems a laughable sum to us, it was substantial enough then. Labor costs were notably high in California, so that Haraszthy was an eager advocate of cheap Chinese labor; he was hurt in the pocketbook when, in 1862, the legislature imposed a tax of $2.50 a month per head on Chinese labor.[42] There may have been other reasons, too, for his financial difficulties; in any event, Haraszthy was willing to listen when he was approached by San Francisco bankers interested in the future of wine who had a scheme to propose to him.

Haraszthy, an irrepressible "developer," had at one time thought of promoting small, independent wine farms by selling parcels of his Sonoma lands and supervising their development as vineyards.[43] Now, however, in 1863, he sold his lands, vineyards, and winery to an organization called the Buena Vista Vinicultural Society. The society, incorporated in April, announced in its prospectus that it had a variety of purposes: to develop land, to quarry stone, and in any other way to exploit its property; but its main aim was to become the biggest winemaker in California, and soon.[44] Haraszthy himself, who held 2,600 of the society's 6,000 shares, was a trustee and the superintendent of the firm; he was joined by such winegrowing Sonoma neighbors as Isidor Landsberger, Emil Dresel, and Major

Jacob Snyder. The crucial backing, though, was provided by the reckless banker and speculator William J. Ralston, lord of the Comstock Lode and builder of San Francisco's Palace Hotel. The prospects of the society looked unbeatable: good vineyard land in a proven area, planted to superior varieties (in part at least—there is evidence that Haraszthy was not so quick to give up the Mission as has been supposed);[45] a winemaking establishment superior to everything else in the state, complete with steam-powered grape crusher and press; and the experience, confidence, and energy of Haraszthy himself presiding over all. The society's declaration that it would, within ten years from 1863, produce more than two million gallons of wine and one million of brandy did not, at the time, seem extravagant.[46]

Scores of Chinese were fed and housed on the Buena Vista property and set to work in the fields and the winery, adding to the vineyard acreage and expanding the winery and its cellars. Wine began to be produced in large quantities, and the profits at the end of the first year surpassed even the optimistic expectations of the promoters. After that first year, however, things did not go well at all. Arpad Haraszthy, back from his studies in the cellars of Epernay, was entrusted with the production of champagne, with dubious results and substantial losses to the company.[47] Business did not grow at the rate so confidently predicted, and there were other sorts of difficulties too—new taxes, for one. The wines were not all they should be either. The Massachusetts editor Samuel Bowles visited Buena Vista in 1865 and was not impressed. It did not, he said, seem a "well managed" enterprise; "nor," he added, "do we find the wines very inviting .... I have drank, indeed, much better California wine in Springfield than out here."[48] In short, the Buena Vista venture was not paying dividends, and Haraszthy, the central figure, quickly came under fire. Stockholders accused him of extravagance and irresponsibility, and it is to be feared that he did not always keep to the windward side of the law: there was a scandal in 1864 about an attempt to defraud the revenue by a scheme for distilling "brandy" from molasses brought in from the Sandwich Islands.[49] At last, Haraszthy had to give way. In 1866 he resigned his position and left forever the property that he had developed so spectacularly in a brief decade.

Haraszthy took refuge at the vineyard and winery near Sonoma owned by his son Attila, but accident and bad luck dogged him there too. The upshot was that in 1868 he left California. The scene of the fourth and final phase of his life—after Hungary, Wisconsin, and California—was Nicaragua, where, somehow, he had managed to obtain a sugar plantation near Corinto, on the Pacific coast, and a permit from the government to produce rum for export.[50] A year later he met his death in circumstances that are not likely ever to be made clear. The sole authority is a letter from his younger daughter Otelia reporting that he disappeared on 6 July, and that his path had been traced to where a large tree grew with branches stretching across a stream:

About the middle of the stream, a large limb seemed to be broken [Otelia wrote], and at the same place, a few days before, an alligator had dragged a cow into the stream

from the bank. We must conclude that father tried to cross the river by the tree, and that losing his balance, he fell, grasping the broken limb, and then the alligator must have drawn him forever down.[51]

Perhaps this was a fitting end for a man who allegedly killed wolves with his bare hands; certainly it maintains the note of the unusual that Haraszthy so strikingly set.

Now that the outline of Haraszthy's activity in California has been sketched, what can we say of his role in the development of the state's winegrowing? He may claim to be the author of California's first treatise on grapes and wine. He was not the first to advertise California wine to the wider markets of the East Coast, but perhaps he did it better than anyone else had so far through his Grape Culture, Wines, and Wine-Making of 1862, and in the articles that he sent to the press throughout the 1860s. His work in bringing the Buena Vista winery to a high level of production was a notable exhibition of entrepreneurial skill. But the three main claims in the Haraszthy legend are all false: he was not the "father" of California winegrowing; he was not the man who first brought superior varieties of grapes to California; and he was not the man who introduced the Zinfandel. Incidentally, he was not a martyr to public ingratitude whose financial sacrifices for the good of the state went uncompensated. He certainly was an energetic and flamboyant promoter, combining the idealist and the self-regarding opportunist in proportions that we can now only guess at. He will remain an interesting and highly dubious figure, of the kind that always attracts historians; but we should no longer take seriously the legend that has grown up about him.