6

The Early Republic, Continued

George Rapp and New Harmony

A kind of appendix to the chapter of winegrowing history at Vevay is that of the German religionists at New Harmony in western Indiana on the Wabash River, some twenty-five miles from its junction with the Ohio. The Harmonists, as they were called, combine two familiar elements in the history of early American winegrowing, being both an organized migration of non-English peoples traditionally skilled in viticulture (most of them came from Württemberg, in the Neckar valley), and a religious community. Led by the German prophet George Rapp, who preached that baptism and communion were of the devil, that going to school was an evil practice, and that Napoleon was the ambassador of God, the Harmonists, whose main social principles were communism and celibacy, left Germany for the United States in 1803.

George Rapp himself had been trained as a vine dresser in Germany, and the main economic purpose of his community was to grow wine. Following the example of Dufour, they tried to secure an act of Congress that would allow them to take up lands along the Ohio for this purpose on favorable terms. Difficulties arose, however, and they were at first compelled to settle in western Pennsylvania, where they were unhappy to find the land "too broken and too cold for to raise vine."[1] They turned instead to distilling Pennsylvania rye whiskey in substantial quantities, but did not quite give up the plan of carrying on the culture of the vine. In 1807 they laid out a hillside vineyard in neat stone-walled terraces, the standard practice of their native German vineyards but a novelty in the United States.[2]

There they planted at least ten different varieties of vine, probably all native Americans: the Cape and the Madeira as grown by the Swiss at Vevay were certainly among them.[3] In 1809 the Harmonists put up a new brick building with a cellar designed for wine storage, and by 1810 they were expecting about a hundred gallons of wine from their vineyard, now grown to ten acres.[4] The carefully kept records of the society show $1,806.05 received in 1811 for the sale of wine, a remarkable—indeed highly questionable—figure, since we are told that their total production two years later was still only twelve barrels.[5] What were the Rappites selling in 1811? In any case, they thought well enough of their 1813 vintage to send some bottles of it to the governor of Pennsylvania, who shared it with some friends and reported that one of them, "an expert," had found that it "resembled very closely the Old Hock ."[6]

The Pennsylvania settlement, sustained by the well-directed combination of agriculture and manufacture, quickly grew prosperous; but it was not what they wanted. In 1814 Rapp made a foray into the western lands, found an admirable site with a "hill . . . well-suited for a vineyard," and determined to lead the community there to resettle.[7] The whole establishment of Harmony—buildings and lands, lock, stock, and barrel—was put up for sale, the vineyards being thus described in the advertisements:

Two vineyards, one of 10, the other of 5 acres, have given sufficient proof of the successes in the cultivation of vines; they are made after the European manner, at a vast expence of labor, with parapet walls and stone steps conducting to an eminence overlooking the town of Harmony and its surrounding improvements.[8]

In 1814 the move began to the thousands of acres that their disciplined labors had enabled them to buy along the banks of the Wabash. They brought cuttings with them from their Pennsylvania vineyards, some of which Rapp gave to the Swiss at Vevay, where he was well received on his way to his new domain.[9] Early in 1815 Rapp's community had planted their New Harmony vineyard; by 1819 they had gathered their second vintage, and by 1824, at the end of their stay on the Wabash, the Harmonists had about fifteen acres in vines producing a red wine of considerable local favor.[10] For the decade of their flourishing, roughly 1815-25, the two centers of wine production at New Harmony and at Vevay made Indiana the unchallenged leader in the first period of commercial wine production in the United States. The scale of production was minute, but, such as it was, Indiana was its fount. At New Harmony, as at Vevay, the successful grape was the Cape, or Alexander; they had also a native vine they called the "red juice grape."[11] The Harmonists naturally yearned after the wine that they had grown and drunk in Germany, and in the first hopefulness inspired by the hillsides of the Wabash, so obviously better suited to the grape than their old Allegheny knobs, they ordered nearly 8,000 cuttings of a whole range of German vines, including Riesling, Sylvaner, Gutedel, and Veltliner.[12] That was in 1816; more European vines were no doubt tried—another shipment was sent out in 1823, for example[13] —but of course

all were doomed to die. The only thing German about the wine actually produced at New Harmony was Rapp's name for it, Wabaschwein .[14]

The Harmonists knew that it would not be easy to establish a successful viticulture, since, as hereditary vineyardists, they understood the importance of long tradition. When, in 1820, the commissioner of the General Land Office made an official request for a report on their progress in viniculture, they answered that they had yet to find "the proper mode of managing in the Climat and soil," something that "can only be discovered by a well experienced Person, by making many and often fruitless experiments for several years." It was all quite unlike Germany, "where the proper cultivation, soil, and climat has been found out to perfection for every kind of vine."[15] On the whole, their experience in Indiana was a disappointment, a disappointment reflected in these interesting observations, written about 1822, by an unidentified diarist who had just paid a visit to New Harmony:

They have sent almost everywhere for grapes, for the purpose of ascertaining which are the best kinds. They have eight or ten different kinds of wine, of different colors and flavors. That from the fall grape, after a few frosts, promised to be good, as at the Peoria Lake, on the Illinois, where, it is said, the French have made 100 hogsheads of wine in a year.[16] But none has done so well as the Madeira, Lisbon, and Cape of Good Hope grapes. Here the best product is 3 to 400 gallons per acre, when in Germany it is 2 to 1500. They sell it by the barrel, (not bottled) at 1 dollar a gallon. Its flavor is not very good, nor has it much body, but is rather insipid . . . .

The culture of it is attended with so much expense and difficulty, while it is so much subject to injury, that it results rather in a loss than a profit . . . .

From all the experience they have had of it, they are only induced to continue it for the sake of giving employment to their people; and, although it does better than at Vevay and New Glasgow,[17] where it is declining, it will, they say, eventually fail, as it did in Harmony in Pennsylvania.[18]

Though they could not make German vines grow on Indiana hillsides, whatever else the Harmonists touched seemed to prosper—at least to the views of outsiders. The numerous travellers, American and foreign, who passed up and down the Ohio Valley in the decade of New Harmony all testify to the neat, busy, and flourishing air of the scene there: "They have a fine vineyard in the vale, and on the hills around, which are so beautiful as if formed by art to adorn the town," an Englishman wrote in 1823, "Not a spot but bears the most luxuriant vines, from which they make excellent wine."[19] How good the wine was in fact can hardly be known now, but one may doubt. One German traveller in 1819, though much impressed by the excellence of the New Harmony beer—"a genuine, real Bamberg beer"—was less pleased by the wine: "a good wine," he called it, "which, however, seems to be mixed with sugar and spirits."[20] The observation is one that could probably have been made of almost all early American vintages that aspired to any degree of palatability and stability: without the spirits the alcohol content would have been too low; and without the sugar the flavors would have been too marked

and the acid too high. Jefferson, too, complained about the difficulty of getting wine free of such sweetening and fortification.

Another German traveller, the aristocratic and inquisitive Duke Karl Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, called at New Harmony during the course of his extensive travels in 1826, just after the Harmonists had sold their community and moved back to Pennsylvania. They had left some wine of their produce behind them, which the duke described as having a "strange taste, which reminds one of the common Spanish wine." An old Frenchman whom the duke met at New Harmony told him that the Harmonists did not understand winemaking, and that their departure would allow better stuff to be produced. The remark probably says more about the relations between Germans and French than about actual winemaking practices. The duke carried his researches further, however, by visiting the newest and last of the Harmonist settlements; this was at Economy, Pennsylvania, where Rapp had taken his community to escape the unhealthy climate and the ill-will and harassment they faced on the remote frontier from the early, uncivilized Hoosiers. There, at Economy, the duke was served by Rapp himself with "excellent wine, which had been grown on the Wabash and brought from there; the worst, as I noticed, they had left in Harmony."[21] The morality of this conduct is a nice point, but however it might be settled, we know from it that the Harmonists took the trouble to select and specially care for their superior vintages.

Economy, a part of which is now preserved as a state park, lay on the Ohio just below Pittsburgh. As the first two Harmonist settlements had done, this third one quickly prospered; and as in the first two, this one also was furnished with a vineyard, and every home had vines thriftily trained along the walls on trellises of unique design. Within a year of the migration from Indiana, there were four acres of vineyards at Economy,[22] and they continued to be developed in succeeding years. A striking piece of information is that, after all the years of struggle at the two earlier sites, the Harmonists, on this their third and last site, were still persisting in trying to grow vinifera. A visitor in 1831, after noting the hillside vineyard at Economy, laid out in stone-walled terraces after the fashion of Württemberg, added that the vines had come from France and from Hungary.[23] If this were the case, and if they did not also plant some of the old, unsatisfactory natives, the Harmonists cannot have produced much wine at Economy.

Nevertheless, Economy itself did not merely continue to prosper after the death of Rapp in 1847; it was propelled into vast wealth through investments in oil and in railroads. In 1874 the historian of American communistic life, Charles Nordhoff, found the place in high good order, including "two great cellars full of fine wine casks, which would make a Californian envious, so well-built are they."[24] In 1889 the young Rudyard Kipling, on his way from India to England, looked in briefly on Economy and noted the contrast between its accumulating wealth and its declining vigor.[25] By that time, if the Harmonists still paid regard to winemaking, their pioneering work had long since been eclipsed by newer and more commercial efforts.

32

A rare item testifying to the interest in winegrowing among the Germans of Pennsylvania in the 1820s.

This reprinting at Reading, Pennsylvania, of a standard German treatise on winegrowing was published

by Heinrich Sage, who tells us that he went to Germany expressly to acquire information on the subject.

The title translated is Improved practical winegrowing in Gardens and especially in vineyards, with

instructions for pressing wine without a press . . . dedicated to American winegrowers by Heinrich B.

Sage . (California State University, Fresno, Library)

As for New Harmony on the Wabash, that had been sold in 1825 to the Welsh mill-owner and socialist Robert Owen, who intended to establish a revolutionary model community as an example to the world.[26] Too many theorists and too few organized working hands quickly put the experiment out of order, and the communitarian days of New Harmony ended two years after the shrewd and practical Rapp had peddled the place to the doctrinaire Owen. New Harmony today is notable among midwestern towns for its lively interest in its own past, but it has long since forgotten the "red juice grape" and its Wabaschwein .

Before the Harmonists had retraced their steps from Indiana, other significant ventures had been made in Pennsylvania in the new viticulture based on the Alexander grape. The pioneer in these was a Pennsylvania Dutchman named

Thomas Eichelberger, of York County, who, in an effort to put barren land to profitable use, engaged a German vine dresser and planted four acres of a slate ridge in 1818. By 1821 Eichelberger had a small vintage; by 1823 his four acres yielded thirty-one barrels and he had added six more acres. He planned to reach twenty. When the word got round that Eichelberger had been offered an annual rent of $200 an acre for the produce of his vines, there was a scramble to plant vineyards in the Dutch country. "There is land of a suitable soil enough in York county," one writer declared, "to raise wine for the consumption of all the United States."[27] The rural papers of the day are filled with calculations exhibiting the absolutely certain profits to be made from Pennsylvania grapes, and by 1830 there were, according to contemporary report, some thirty or forty vineyards around York and Lancaster.[28] Many amateurs throughout the middle states had also been inspired by the example of York County to attempt a small vineyard.

The grapes most commonly grown were called the York Madeira, the York Claret, and the York Lisbon—all, apparently, variations on the Alexander, though the York Madeira may be a different variety. Later, some of the new hybrid introductions that began to proliferate in the second quarter of the century were used, but these eventually succumbed to diseases and so put an end to the industry. Not before it had made a lasting contribution, however: as U. P. Hedrick writes in his magisterial survey of native American grape varieties, "a surprisingly large number have been traced back to this early center of the industry, so many that York and Lancaster Counties, Pennsylvania, must be counted among the starting places of American viticulture."[29]

Bonapartists in the Mississippi Territory

An unlikely agricultural colony, very different from the religious communities like Rapp's Harmonists, or refugees from religious persecution, like the South Carolina Huguenots, was formed in 1816 out of the refugee Bonapartists, mostly army officers, who had then congregated in considerable numbers in and around Philadelphia. On his second restoration, after the nightmare of the Hundred Days had been dispelled at Waterloo in 1815, Louis XVIII prudently determined to get rid of the more ardent partisans of the emperor, most of them officers of the Grande Armée or political functionaries under Napoleon. Decrees of exile were issued against some, and the fear of official vengeance determined others to leave. Most of them chose to go to the United States, and of these, many chose Philadelphia, not far from where Joseph Bonaparte was spending his exile at Borden-town, New Jersey. How the idea arose and by whom it was directed we do not know, but by late 1816 the French officers in Philadelphia, with various French merchants and politicians, had organized an association with the vague purpose of "forming a large settlement somewhere on the Ohio or Mississippi . . . to cultivate the vine."[30] They called themselves the French Agricultural and Manufacturing So-

ciety and included among their members Joseph Lakanal, one of the regicides of Louis XVI and the reformer of French education under the Revolution. He was sent out to explore the country for suitable sites, and ventured as far as southwestern Missouri on his quest.[31]

The plan soon grew more distinct. The Mississippi Territory was then being highly promoted and rapidly settled. It had, besides, the attraction of lying within the old French territory; Mobile was a French city, and New Orleans was not too remote. They would go, then, to what is now Alabama, where they had been assured that they would find a climate like that of France and a land adapted to the vine and the olive. An agent was sent to Washington to secure a grant of public lands, and in March 1817 Congress obliged by voting them four townships to be paid for at two dollars an acre on fourteen years' credit.[32] The financial arrangement was the same as that made with Dufour in 1802, and no doubt that precedent was consulted. But the scale of all this was much bigger than that of Dufour's project; this was not a family, but a whole community that was to undertake a new enterprise of large-scale winegrowing.

There were 350 members of the group, officially the "French Agricultural and Manufacturing Society," but more often referred to as the "Vine and Olive Association" or the "Tombigbee Association," after the river along whose banks they meant to settle.[33] Their grant extended over 92,000 acres. It was evidently the intention of Congress to make the experiment large-scale and coherent: no individual property titles would be granted until all the property had been paid for, and so, it was hoped, since the colonists thus could not sell their holdings, they would keep at their work. The whole vast tract was meant to remain exclusively French and was to be devoted mainly to vines and secondarily to olives, all tended by "persons understanding the culture of those plants." By the terms of the contract made between the association and the secretary of the Treasury, they were, within seven years of settlement, to plant an acre of vines for each section of land (that is, a total of about 140 acres at a minimum).[34]

Very shortly after receiving their grant, whose exact location was not yet determined, the first contingent of settlers, about 150 in number, sailed for Mobile, from there went up the Tombigbee to its junction with the Black Warrior River, staked their claim, and laid out the town of Demopolis.[35] The affair attracted much attention, and even the English were impressed: a London paper was moved to call the project "one of the most extraordinary speculations ever known even in America."[36] But the whole thing was grandiose, impetuous, and vague—grandiose because it was seriously maintained that the French would supply the nation's wants in wine;[37] impetuous because the would-be planters began settling even before they knew where they were to settle, with disastrous consequences, as will be seen; vague because no one knew anything about the actual work proposed or had any notion of ways and means. The idea that the veterans of the greatest army ever known, men who had been officers at Marengo, Austerlitz, Moscow, and Waterloo. would turn quietly to the American wilderness to cultivate the vine and the olive.

emblems of peace, has a kind of Chateaubriandesque poetry about it, but little to recommend it to practice. There is a certain charm in the splendid incompetence displayed, but the charm is hardly sufficient to offset the fact that the emigrants paid a heavy cost in disease, death, and wasted struggle. They do not seem even to have heard, for example, of the work with native vines done by Dufour, and had no thought of attempting to grow anything but vinifera.

The first step in the debacle was the discovery, when the surveyors arrived, that Demopolis was laid out on land that did not belong to the French grant.[38] The settlers had to abandon their clearings and cabins and to found another settlement, which they called Aigleville after the ensign of the Grande Armée. Meantime, the distribution of lands within the grant was being drawn up on paper in Philadelphia after the first settlers had already made their choice on the spot, and of course the two divisions did not coincide. Once again the beleaguered French had to reshuffle their arrangements. Their lands, in the rich Black Belt of Alabama, were then a difficult mixture of canebrake, prairie, and forest, and were not even hospitable to the native grape, much less to the imported; as for the olives, the winters destroyed them at once. Fevers killed some of the settlers; discouragement sent even more to look for their fortunes elsewhere, a circumstance that at once made the original contract impossible of fulfillment. That had stipulated that no title would be given until all the contracting parties had met their terms, and if some of them simply abandoned the work, then the remnant were left with no means of satisfying the requirements. The provision was altered in 1822 when it was clear that the original plan was not going to work out.[39] Stories, apocryphal no doubt, but expressive, were told of the French officers at work felling trees in their dress uniforms and of their ladies milking or sowing in velvet gowns and satin slippers.[40]Toujours gai was the watchword; no matter how desperate the circumstances, in the evenings the French gathered for parties, dancing, and the exchange of ceremony. Such stories sound like Anglo-Saxon parodies of French manners, and probably are. But they testify to the fact that the French of Alabama struck their neighbors as very curious beings, almost of a different order.

It is sometimes suggested that these French soldiers were merely trifling—that they never seriously intended to labor at agriculture but were simply biding their time before Napoleon should return, or some other opportunity for adventure turn up.[41] That was certainly true of some. But others seem to have worked in good faith. Some vines were reported to be planted in 1818; by the end of 1821 there were 10,000 growing, though the French complained that most of the cuttings that they persistently imported from France arrived dead or dying.[42] A few vines lived long enough to yield a little wine, but it was found to be miserable stuff, coming as it did from diseased vines picked during the intensest heats of summer and vinified under uncontrollably adverse conditions.[43] Nevertheless, the usual optimism of ignorance was still alive; on meeting several of the Frenchmen, one traveller through Alabama in 1821 reported that "they appear confident of the success of the Vine."[44]

Since the settlers were under contract with the Treasury to perform their

33

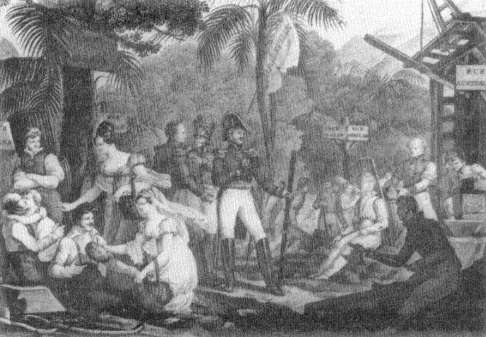

One of five panels of hand-painted French wallpaper showing idealized scenes from the

Alabama Vine and Olive Colony. This one presents the building of Aigleville. The street

signs—"Austerlitz," "Jena," "Wagram"—bear the names of Napoleon's victories. (Alabama

Department of Archives and History)

promise, the Congress made inquiry into their progress from time to time. From the report for 1827 we learn that there were 271 acres in vines, but that these were not set out in the form of ordinary vineyards; instead, they stood at intervals of 10' × 20' on stakes set in the midst of cotton fields! By this time, the spokesman for the association had acquired at least one item of wisdom, for he informed the secretary of the Treasury that "the great question seems to be the proper mode of cultivation, and, instead of seven, perhaps seventy years may be required correctly to ascertain this fact."[45] The last official report, dated January 1828, states that the drought of the preceding summer had killed their vines, but that the French were "now generally engaged in replanting."[46] On this note of stubbornness in the face of defeat, the French Vine and Olive Association died out; some members returned to the eastern cities, some to Europe; others went to Mobile or points west.

The net result of the French ordeal in Alabama was to make it clear that, if any grapes were to grow there, they must be natives. In 1829 an American who had managed to obtain lands within the French grant reported that he had observed the repeated failures of the French over several years and attributed the result to their using vinifera. The only grape that ever succeeded was one—unnamed—that had been sent to them from New Orleans by the agent there of the Swiss at Vevay, and

which the French vigneron who planted it called the Madeira.[47] Thus, circuitously and accidentally, was confirmed what they might have learned directly from Du-four's experience: with the natives there was a chance; without, none.

John Adlum, "Father of American Viticulture"

It is now time to take up a story of success, the episode that is traditionally identified as the true beginning of commercial winegrowing as it developed in the eastern United States. The man who is familiarly called the "Father of American Viticulture"—how well-deserved that title is will appear from this sketch of his work—was Major John Adlum (1759-1836), of The Vineyard, Georgetown, District of Columbia.[48] Adlum was born in York, Pennsylvania, and as a boy of seventeen marched off with a company of Pennsylvania volunteers to join the Revolution, but was captured by the British at New York and sent back home. Though he later held commissions in the provisional army raised in 1799, from which he derived his title of major, and in the emergency forces raised in the War of 1812, Adlum, after his brief experience of war, took up surveying as a profession. He chose a good time, for after the Revolution the western lands of Pennsylvania and New York filled up rapidly, allowing Adlum to make a modest fortune through the ready combination of surveying and land speculation. By 1798 he was able to retire, and he settled then on a farm near Havre de Grace, Maryland, at the mouth of the Susquehanna River, along whose course he had often travelled in his surveying work. He probably planted a vineyard at once at Havre de Grace, for he seems to have been interested in grapes even before his retirement; while carrying out his surveys he took notes on the native grapes growing wild in the woods and along the streams of Pennsylvania—red and white grapes growing on an island of the Allegheny, black grapes at Presque Isle, where the French were said to have made wine from them, and black grapes along the Susquehanna all came under his notice and suggested that, from such fruit, "excellent wines may be made in a great many parts of our Country."[49]

Nevertheless, his first plantings were of European vines, evidence of the strength of the grip that, at this late date in American experience, the foreign vine still had upon the minds of American growers. It did not take Adlum long, however, to decide that he had made a mistake. When insects and diseases overwhelmed his vinifera vines, he had them grubbed up and planted native vines instead.[50]

One of these was the Alexander, and from it Adlum succeeded in making a wine that had a significant success—he later admitted that his method with that batch was an accident that he could never afterwards duplicate.[51] Nevertheless, he made the most of what he had, which was, in the first place, an astute sense of publicity; he sent samples of his wine to the places and persons where they might have their most effective result. One went to President Jefferson, and with him the

34

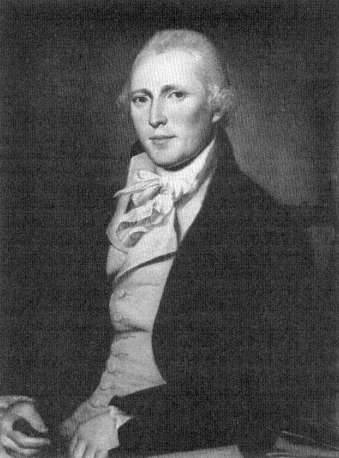

John Adlum (1759-1836), whose Georgetown vineyard produced the first commercial

wine in the settled regions of the country. Adlum gave a tremendous boost to the

development of winegrowing by his introduction of the Catawba grape and by his

publications on grape growing and winemaking in the 1820s. (Portrait attributed to

Charles Willson Peale, c. 1794; State Museum of Pennsylvania / Pennsylvania

Historical and Museum Commission)

wine made a home shot. It was, the president wrote, a fine wine, comparable to a Chambertin, and he advised that Adlum look no farther for a suitable wine grape but press on with the cultivation of the Alexander. He should forget about foreign vines, "which it will take centuries to adapt to our soil and climate."[52] Adlum agreed, but observed with the doubtfulness of experience that Americans were not yet quite ready for wine from American grapes—as soon as they knew what they were drinking, they objected to it, though they might have been praising it a moment before.[53] The remark is one the truth of which most eastern winemakers even today will regretfully assent to. But Adlum was determined to persist, even though

he knew that, as a prophet of American wine, his own country would likely be the last to honor him.

In 1816 Jefferson wrote again to Adlum, having been stirred by a fresh prospect of planting wine vines, and learned that great changes had occurred in his correspondent's circumstances. Adlum was now living in Georgetown, on property near Rock Creek, above the Potomac, where he had settled after leaving Havre de Grace in 1814.[54] At the time of Jefferson's letter, Adlum had not yet set out a Georgetown vineyard. It may have been Jefferson's inquiry that aroused Adlum again; it may have been that Adlum had the thought in mind himself; in any case, he was soon back at planting vines, this time on a different basis and with a wholly different success.

The Vineyard, as he called his farm, was a property of some 200 acres; the vineyards themselves were on the south slope of a hill running down to Rock Creek, now part of Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C. A poetically inclined visitor in the early days found that they made a quiet, sequestered scene; rows of vines, ranged one above the other, rose from the base of a hill washed by a willow-fringed stream, beside which a black vine dresser gathered willow twigs for tying up the shoots of the vines that lined the hill above.[55] The picture is attractively idyllic, but perhaps a bit en beau . What Adlum had was in fact quite a modest establishment, with nothing of the grand château about it: from the vantage of another observer, the vineyard was seen as a "patch of wild and scraggy looking vines; the soil was artificially prepared, not with rich compost, but with pebbles and pounded oyster-shells."[56] The whole property was not large, and the vines occupied but a small part of the whole—some four acres by 1822.[57]

The first vintage at Georgetown of which we have report was made in 1822 and consisted of 400 gallons, in no way distinguishable from other vintages yielded by native vines before.[58] There was this difference, though: it was the produce of the nation's capital, and therefore noticeable and promotable in a way that, for example, the vintages of Dufour's Swiss on the remote banks of the Ohio were not. Here, for example, is how the editor of the American Farmer , a superior publication emanating from Baltimore, greeted Adlum's first offering:

Fourth of July Parties

Would manifest their patriotism by taking out a portion of American wine, manufactured by Major Adlum of the District of Columbia. It may be had in varieties of Messrs. Marple and Williams, and the Editor of the American Farmer will be thankful for the candid opinion of connoisseurs concerning its qualities.[59]

If any patriot-connoisseurs heeded the request, their responses do not appear in the American Farmer , but the publicity can have done Adlum no harm. Yet one wonders what Adlum could have been offering? July is too early by any stretch of the imagination for the vintage of 1822 to have been put on sale. And in any case, Adlum wrote to the American Farmer on 17 September 1822 that he had just then completed his winemaking.[60] The vintage of 1821, we know from Adlum's testi-

mony, had all turned to vinegar.[61] Possibly wine from 1820 was what was advertised in 1822, but there is no record of any production in 1820.

As Adlum himself explained in the American Farmer , in 1822, he had only just begun his work then: he had some vines of "Constantia" and some vines of what he called "Tokay"—not anything like real Tokay, as we shall see, but something portentous nonetheless. He had cuttings for sale, Adlum added, and he hoped himself to have some ten acres in vines soon.[62]

In the next year, Adlum's work was translated to a different plane. His "Tokay" had fruited for the first time in 1822, and the wine that he had made from it in that season developed into something better than any native grape had yielded before. Adlum lost no time in advertising his success, and, as others began to admire, he did not let any consideration of modesty restrain his high claims for the quality of the "Tokay" grape. Jefferson, of course, was one of the first to receive a bottle of Adlum's Tokay; James Madison was another.[63] Jefferson's reply, though polite, must have been a disappointment to Adlum, who may have hoped for something as extravagant as the great man's earlier comparison of Alexander wine to Chambertin. This time, Jefferson restricted himself to the observation that the Tokay was "truly a fine wine of high flavor."[64] That was good enough for promotional purposes; Adlum sent Jefferson's letter (and a bottle of Tokay) to the editor of the American Farmer , where a notice appeared in the next month. Later, Adlum reproduced Jefferson's letter in facsimile as the frontispiece of his book on winegrowing.

The history of the "Tokay" grape, which thus first came to public notice in 1823, is fairly circumstantial, though a number of questions remain as to its origin and early distribution. In sending a bottle to Jefferson, Adlum stated that the vine came from a Mrs. Scholl in Clarksburgh, Maryland, that a German priest had said the vine was "the true Tokay" of Hungary, but that Mr. Scholl (now dead) had always called it the Catawba.[65]

Adlum took cuttings from Mrs. Scholl's vine in the spring of 1819; by 1825 he had determined that "Tokay" was a misnomer, and reverted to the late Mr. Scholl's name, Catawba,[66] which belongs to a river rising in western North Carolina and flowing into South Carolina. Traditionally the grape was found first not far from present-day Asheville, in a region of poor, thinly timbered soil. Whether Scholl had any information to justify the name he gave the grape is not known. After the success of the grape had led to its wide distribution, a good many different stories about its origin were published, but none authoritative enough to settle the matter.[67]

The same uncertainty attends the botanical classification of the Catawba. Early writers called it a labrusca; Hedrick agrees, but adds that it must have a strain of vinifera as well.[68] It has the self-fertile flowers of vinifera, a trait that combines with its improved fruit quality to confirm its vinifera inheritance. As to the character of the grape, that is well established. After more than a century and a half of cultivation, it still remains one of the important native eastern hybrids; for winemaking, it is one of the three or four most valuable of such grapes. The fruit of the Catawbâ is

35

The Catawba grape, introduced by John Adlum in the early 1820s, the first

native hybrid to make a wine of attractive quality. Its origins are uncertain,

but after more than a century and a half of cultivation, it still retains a place

in eastern viticulture. (Painting by C. L. Fleischman, 1867; National Agricultural

Library)

a most attractive lilac, a light purplish-red, yielding a white juice which is definitely foxy, after the nature of its labrusca parent, but which may be transformed into a still white wine that Philip Wagner describes as "dry to the point of austerity" and having "a very clean flavor and a curious, special, spicy aroma."[69] Its superiority to the other grapes available in its day quickly led to its trial all over the inhabited sections of the United States; growers then learned that it presented some severe problems, being susceptible to fungus diseases and, in northern regions, failing to ripen except in special locations. It found a home in Ohio, first along the Ohio

36

John Adlum's was the first book on winegrowing to be published in the United

States as opposed to the British North American colonies. It was also the first

book to assume that American winegrowing would have to be based on native

American varieties. Both facts give the Memoir a special status in the early literature

of American winegrowing. (Huntington Library)

River and later in the Lake Erie district, and in New York in the Finger Lakes country. It remains, in both states, a staple grape for winemaking, particularly in the production of sparkling wine.

From the evidence of his own descriptions of his winemaking methods, and from the remarks of some critics, it appears that Adlum himself did not make very good wine from his Catawba. Though he disapproved of the established American practice of adding brandy (most often fruit brandy of local production) to wine in order to strengthen and preserve it, he did not hesitate to add large quantities of sugar to the must, so much that the juice would not ferment to dryness. The horticultural and architectural writer Andrew Jackson Downing, a good judge, remembered Adlum's wine as "only tolerable";[70] Nicholas Longworth, who may be said to have succeeded to Adlum's work with Catawba, agreed that Adlum's wine was poor, not only for its artificial sweetness but because, he reported, Adlum was not above eking out his superior juice in lean years with the juice from the wild grapes growing in the woods that surrounded his vineyard.[71] This practice Longworth politely attributed to Adlum's "poverty" (whatever the size of Adlum's fortune when he retired in 1798, it does not seem to have been adequate to carry him easily to the end in 1836). After all these qualifications and reservations have been made, the main point remains: Adlum had found a grape from which good wine might be made; he had been quick to recognize the fact; and he had been able to publicize it effectively. At the time, and given the circumstances, he had done precisely what the long struggle to create an American winegrowing industry needed.

By some providence, the introduction of Adlum's Catawba wine coincided with the publication of Adlum's book on grape growing and winemaking: his Memoir on the Cultivation of the Fine in America, and the Best Mode of Making Wine , published in Washington early in 1823,[72] appeared almost together with the first distribution of Catawba. Perhaps he planned it that way. In any event, the two strokes, the new book and the new wine together, have made Adlum's mark on the record of American winegrowing permanent and visible to a degree hardly matched by any other individual's. His book is interesting, and original to the extent that it chronicles his own experience with vine growing and winemaking, going back to his residence at Havre de Grace at the end of the eighteenth century. As a treatise on viticulture, it is derivative; Adlum did not pretend otherwise, and freely acknowledged the fact that he was following the lines laid down by established European writers. He thus has little or nothing to say on such crucial subjects as the diseases that had to be faced by any American viticulturist. He spends more time on winemaking, but here, too, his achievement is not remarkable. His disposition to use too much sugar in his wine has already been noticed. Moreover, he recommended such practices as fermentation at high temperatures—up to 115° Fahrenheit!—which would horrify winemakers today.[73] But one may make many allowances for Adlum. He wrote with as much independence as could be expected in his circumstances, he clearly understood the importance of native vines, he

firmly opposed the bad practice of drowning wines in brandy, and, in company with all of his notable predecessors, he acted with a conscious sense of patriotic selflessness: "a desire to be useful to my countrymen, has animated all my efforts," he declared in the preface to his Memoir . As he wrote to Nicholas Longworth not long after the triumphant introduction of the Catawba, "in introducing this grape to public notice, I have done my country a greater service than I should have done, had I paid the national debt."[74] And his confidence was infectious. James Madison, in sending two copies of Adlum's book to the Agricultural Society of Albemarle, wrote that now "nothing seems wanting to the addition of the grape to our valuable productions, but decisive efforts."[75]

For the next half-dozen years after he had brought Catawba wine to the public for the first time, Adlum was the recognized oracle on the subject of wines and vines in America. He wrote frequently to the agricultural press—a significantly larger and more influential part of the national press in those rural days than now—describing his practices and setting forth his prescriptions for others. He circularized the great men of the day to attract their attention to the cause of wine-growing, usually sending a bottle of his produce to help make the point; he lobbied the agricultural societies to get them to recognize viticulture and winemaking as activities worthy of official encouragement; he tried to get the federal government to establish a national vineyard in the District of Columbia in which the many varieties of native vines might be planted "to ascertain their growth, soil, and produce, and to exhibit to the Nation, a new source of wealth, which had been too long neglected."[76] Since the intensity of his enthusiasm far exceeded that of the institutions to which he appealed, he did not get very far immediately. But probably much of what we now have is owed to the example he set.

Certainly Adlum's activities had something to do with the noticeable growth of interest in winegrowing that spread over the United States in the 1820s. Adlum himself published exciting figures on the profits to be made from small vineyards, such as almost every American might reasonably plant. In 1824 he notified the public that the demand for cuttings from his vineyard was already growing beyond his ability to supply.[77] In 1825 he was able to boast that he had aroused national interest: "I have correspondents from Maine to East Florida, on the sea-board, and in the states of Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee, to the north and west, on the subject of planting vineyards and making wine."[78] It was in this year, probably, that the wealthy Ohio lawyer and landowner Nicholas Longworth visited Adlum and obtained from him cuttings of the Catawba vine:[79] the results of that encounter form part of another chapter. In 1827 Adlum had the dubious pleasure of inspiring a new contribution to the literature of American winegrowing. The work was a treatise in verse called The Vigneron , published in Washington, D.C., by one Isaac G. Hutton.[80] This strange performance, touching on temperance, soils, planting, cultivation, and other subjects, prints an essay by Adlum "On Propagating Grape Vines in a Vineyard" as an appendix, and also makes such familiar allusion to Adlum as to show that, if he did not beget the poem, he must at least have known that it was being perpetrated.[81]

All over the country waves were felt and echoes heard from the stir that Adlum had made. From South Carolina to New York, farmers, nurserymen, and journalists paid a new attention to the grape, not wholly because of Adlum, but in large part because of the fact that he had done well with a native grape at last and was equipped to publicize what he had done. In Maryland, for example, Adlum had been particularly aggressive in advertising his work, but met a disappointing reluctance on the part of the state agricultural society to do anything about viticulture.[82] Then, in 1828, a company of private gentlemen received a charter from the state to form the "Maryland Society for Promoting the Culture of the Vine," capitalized at $3,000, and furnished with many respectable names among its officers.[83] The intention of the society was to show the way towards scientific advance in vine growing and winemaking. Its plan, evidently inspired by Adlum's notion of a national vineyard, was to establish a small vineyard in which trials could be made of both European and native grapes, and, by its example, encourage the formation of other such societies. After a good deal of early publicity, however, not much seems to have been done. The society still had not managed to find land for a vineyard a year after its founding, and hence could do nothing towards hiring apprentices, selling cuttings, holding exhibitions, and diffusing information as it proposed to do. Perhaps the most interesting thing about the society is the fact that, even though it was called forth by Adlum's success with the Catawba, it still proposed to experiment with vinifera; it marked, as Hedrick has noted, the last organized effort to grow European grapes in eastern America—or rather, the last before the renewed trials of the late twentieth century.[84] Of course, the untried assumption that vinifera would grow here continued to be widespread among individuals. S. I. Fisher, for example, in his Observations on the Character and Culture of the European Vine (Philadelphia, 1834), argued that if we would only imitate the vine growing practices of the Swiss, we would succeed in acclimating the foreign vine. Fisher recommends, too, that Legaux's old Pennsylvania Vine Company should be revived for the purpose.

In 1826 Adlum published another treatise—a pamphlet, really—under the title of Adlum on Making Wine ,[85] but his importance now was less as a winemaker than as a nurseryman promoting the wide distribution of native grapes in a country now at last prepared to believe in them. Adlum used a part of his Memoir as a catalog of his nursery, offering cuttings for sale: the list of the varieties he had available is an instructive record of the state of varietal development then. He includes a number of vinifera grapes, but the heart of the list lay in the native vines: "Tokay" (as he then called the Catawba), Schuylkill Muscadel (Alexander), Bland's Madeira, Clifton's Constantia (a variant of the Alexander), Muncy (later affirmed to be Catawba), Worthington, Red Juice, Carolina Purple Muscadine, and Orwigsburgh. The Red Juice grape is presumably that which the Harmonists are reported to have grown along with the Alexander; the Worthington is probably the variety better known as Clinton, a hybrid of riparia, labrusca, and some vinifera; it was later much used for red wine, but without giving much satisfaction—the fruit, Hedrick says, is "small and sour," the wine "too raucous."[86] Bland's Madeira is a labrusca-

vinifera hybrid like the Alexander, and of almost as early discovery as the Alexander. Colonel Theodorick Bland, of Virginia, brought it to notice just before the Revolution, and there are reports of it under various names—Powel or Powell is the most common—in vineyards in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere in the early nineteenth century. Bland's Madeira was probably the "Madeira" that Dufour obtained from Legaux and grew in Kentucky and Indiana, but we cannot be sure.

In 1828 Adlum brought out a second edition of the Memoir , in which the list has been increased by the addition of four more grapes: an unnamed variety from North Carolina, two labruscas called Luffborough and Elkton, and Isabella. The last is a superior chance hybrid of vinifera and labrusca, introduced and promoted by the Long Island nurseryman and viticulturist William Prince as early as 1816. Originating, probably, in South Carolina, it was the chief alternative to Catawba for many years, for it ripens earlier than Catawba and is therefore preferred by growers in the middle Atlantic and New England states. Had Prince made wine in commercial quantities from the Isabella and publicized it, he might well have challenged Adlum for the position as the first to sponsor a good native grape. Adlum's list is a reasonably complete enumeration of what an American winegrower had to work with at the end of the first quarter of the nineteenth century. All of these varieties were accidents, the result of spontaneous seedlings; both the Isabella and the Catawba, the best two of the lot, have serious cultural defects and are susceptible to diseases that could not then be controlled; none was fit for the production of red wine, a severe limitation if one agrees that it is the first duty of a wine to be red. It was not, in short, much of a basis to work on, but it was all that was available up to the decade before the Civil War. Then there was a great and sudden increase in the number of varieties available, thanks to a belated but enthusiastic outburst of interest in grape breeding.

One of the last episodes in Adlum's career as a propagandist of winegrowing was his petition addressed to the U.S. Senate in April 1828 stating his claim to recognition for his work as a vineyardist and winemaker and requesting that the Senate take steps to make the newly published second edition of his Memoir "useful to the United States, and of some advantage to your petitioner ."[87] The Senate committee on agriculture, to which the petition was referred, proposed that the Treasury buy 3,000 copies of Adlum's book for distribution by members of the Senate, but the proposal struck the senators as unorthodox and was defeated.[88] It seems reasonable to suppose that Adlum needed the money; Longworth, as we have already seen, noted Adlum's "poverty," and there is further evidence of his neediness in 1831, when Adlum laid claim to a tiny pension for which he was eligible as a soldier in the Revolution.[89] From 1830 until his death in 1836 he does not figure in the public discussion of grapes and wine, though that went on in full flow. Adlum's name fell into obscurity after his death; his modest home in Georgetown stood until, derelict, it was demolished early in this century; the knowledge of his burial place was, for a long time, lost; and the record of his work was forgotten

until brought back to light by the researches of the great botanical scholar and writer Liberty Hyde Bailey at the end of the nineteenth century.

As with most "Fathers" of institutions or of complex inventions, like the airplane or the automobile, Adlum can hardly be claimed to have been sole father to American viticulture. His establishment was at no time anything but a very small affair; he was not the first to introduce a usable hybrid native grape; he was certainly not the first to produce a tolerable wine; nor was his Memoir the first American treatise on the subject. It would be more sensible to say that he came at the right time in the right place, and that he is fully entitled to the credit of introducing the Catawba and of knowing how to promote it. After Adlum, the history of wine in eastern America is a different story.

The South in the Early Republic

A brief look at the South will close this chapter. The South was not merely the source of usable native hybrids—the Isabella and Catawba from the Carolinas; Bland's grape and the Norton from Virginia. It also had a part in the many winemaking trials made after the Revolution.

Despite the presence of such distinguished amateurs as Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe, Virginia was not one of the leaders in the development of viticulture and winemaking in the early days of the Republic. No doubt many private gentlemen kept up their interest in the subject: Adlum reported that the Virginians were more eager for cuttings from him than any others.[90] Josiah Lockhart, for instance, of Frederick County, bought 2,000 vines of Catawba from Adlum and was producing a few gallons of wine by 1827.[91] One notable event, of considerable importance for the future, was the introduction of the Norton grape by Dr. D. N. Norton of Richmond, Virginia. Sometime around 1820 Dr. Norton planted seed from a vine of the native grape called "Bland" that had fruited near a vinifera grape; one of the resultant seedlings he selected for its superior qualities, which would later be recognized by commercial plantings in Virginia, Missouri, and elsewhere.[92]

Something has already been said about the Scuppernong wine of North Carolina, which had reputation enough to attract Jefferson's interest. "Scuppernong" properly refers to a white variety of the species rotundifolia, the muscadine grape, a variety first brought to notice in North Carolina and much cultivated there from the early nineteenth century on. The popularity of the variety has led to the name Scuppernong being used for muscadines generally, but I restrict it to its original reference. The wine that Jefferson drank and liked was the produce of well-to-do planters around Edenton and Plymouth in the low country on Albemarle Sound; some of this, at least, came from cultivated vineyards. Whether grapes from wild vines were also used is unclear, but seems highly likely. Farther south, Scuppernong wine was almost a vin de pays for the poor; all along the Cape Fear River for a distance of seventy miles, we are told, farmers made wine from the wild grapes and

used it "as freely as cider is used in New England."[93] Observers from time to time noted the ease with which such wine was produced, prompting them to wonder whether it might not be promoted from a hobby or cottage industry to become a staple product for the enrichment of the state.[94] Certainly North Carolina needed such a thing, for its agricultural economy in the first part of the century was well-nigh desperate, the consequence of reckless farming and exhausted soils. More land lay abandoned than was actually in production, and the population declined with emigration.[95] The State Board of Agriculture recognized the possibility of grape culture by distributing vines in the state from 1823 to 1830; but, though the newspapers wrote of what might be done, little in fact came of the effort to turn the worn-out lands of the state into vineyards.[96]

The possibilities of the high ground in the western part of North Carolina, so different from the low and swampy coastal plain favored by the muscadine, were also explored. Around 1827 the state legislature made a grant of 500 acres in the Brushy Mountains of Wilkes County, in the Blue Ridge country, to a Frenchman who undertook to grow grapes experimentally there.[97] What he did, or whether he did anything, are questions for which, as so often happens, no record has been found to answer.

It is in South Carolina, with its intermittent but persistent history of grape growing, going back to the early Huguenot emigration, that much of the interesting work is to be found. Towards the end of the century, the South Carolina Society for Promoting Agriculture (later the Agricultural Society of South Carolina) attempted to assist winegrowing along the familiar lines of importing cuttings from Europe and distributing them for trial,[98] with the usual result: the members were "inexperienced in the peculiar culture of the vine, their labourers were hirelings who did but little, and finally their funds failed them."[99] The one essential thing omitted from such a recital is that the climate and diseases killed the vines quite independently of all the other failures. After this disappointment, the society tried another tack by subsidizing a self-proclaimed expert to cultivate vines near Columbia. A contemporary historian says laconically that "their liberality was misapplied."[100] It is not clear whether this person was the same as "one Magget" who obtained a grant from the legislature around 1800 for the purpose of developing viticulture.[101] Perhaps so; and perhaps it was the same person who in November 1798 gave the address to the Agricultural Society published anonymously as "A Memorial on the Practicability of Growing Vineyards in the State of South Carolina." This was filled with extravagant claims and unreal calculations, demonstrating that, unlike cotton, rice, tobacco, and indigo, the grape presented "an inexhaustible source of riches and opulence."[102]

More productive than the publicly supported efforts were those of individual vineyard owners, of whom there had always been many in South Carolina. The focus of activity after the Revolution shifted from the coast at Charleston, or along the Savannah River, to higher ground around the newly established capital at Columbia and beyond. Benjamin Waring raised grapes and made wine as early as

1802 at Columbia; he was evidently working with a superior selection of native grapes, for he was able to produce wine without added sugar, though with one gallon of brandy to every twelve of juice—a considerable dose to us but a modest measure then.[103] Another, later, Columbia grower was James S. Guignard, who for many years grew Catawba and Norton grapes, as well as one that he called "Guignard."[104] Samuel Maverick, best known for his pioneering work in establishing the cotton culture of the South, was an enthusiastic viticulturist too. At his estate of Montpelier, at Pendleton in the far western corner of the state, Maverick made trials of various grapes, both native and foreign, and of different methods of training, as well as experimenting with soils, fertilizers, and horticultural methods. By 1823 Maverick had nearly fifty varieties growing and with the typical optimism of the time predicted that wine would soon be as valuable to the South as cotton then was.[105] When Caroline Olivia Laurens, wife of Henry Laurens, Jr., visited Maverick in July 1825, she found him full of proselytizing zeal. First he presented the party with "wine of his own manufacturing, equal to Frontinac," and then "he conducted us to his vineyard, which covers an acre or more of land. . .. The old man seemed very desirous that his neighbors should try the cultivation of the vine; he said that he thought this as good a country for grapes as the South of France, and he had no doubt that in a few years wine will be as lucrative a commodity as cotton."[106]

The most active and effective grower was Nicholas Herbemont of Columbia, who began growing grapes about 1811 and who did much to advertise the possibilities of winemaking in South Carolina for the next twenty years. I have not been able to learn much about him. He was evidently French-born, rather than a descendant of the South Carolina Huguenots.[107] He is sometimes referred to as "Doctor," but, on his own authority, he had no claim to the title.[108] In any case, he was an articulate and literate man, writing often for the agricultural press. Like Adlum, he was interested in the technicalities of winemaking and in the search for better native varieties. It is no surprise that, as a Frenchman, he did not immediately concentrate upon the native grapes; it is said that he returned to France in order to bring back vinifera vines to his adopted country.[109] But experience made it clear that success lay with the natives.

Herbemont's best wines came from a grape that he called Madeira, and that others called Herbemont's Madeira; it is now known simply as Herbemont. A member of the subspecies of aestivalis called Bourquiniana, the Herbemont grape probably contains vinifera blood as well. It is eminently a southern grape, sensitive to cold and requiring a long season; given the right conditions, Herbemont is that rare thing among natives, a grape with a good balance of sugar and acid. The white wine that Herbemont made from this grape he called "Palmyra wine" after his farm at Columbia.[110] It is much to be regretted that this excellent practice of naming the wine after the place of its production did not set a clear precedent and so spare us the clarets, madeiras, champagnes, burgundies, and ports whose borrowed names have confused and obstructed the development of a distinctive range of

American types and terms. Herbemont's other favored grape was the Lenoir, another variety of Bourquiniana, also restricted to the South, and giving a red wine better than the average expected from other native grapes—a very guarded praise. Herbemont was not the discoverer or the exclusive promoter of these grapes, both of which had an earlier history quite independent of him. But he did bring them to public notice in connection with his own successful manufacture of wine and he deserves to have his name perpetuated by the first of them.

Like all native winegrowers, he had to overcome much prejudice. The South Carolinian lawyer and politician William John Grayson reported that he and other legislators once sampled the wine of the "urbane and kind hearted" Herbemont. Grayson thought the wine "very pleasant. But not so my more experienced colleagues, adepts in Old Madeira and Sherry; they held the home article in very slender estimation. They thought it, as they said, a good wine to keep, and were content that it should be kept accordingly."[111]

Unlike Adlum, Herbemont did not produce a book on winegrowing, though a series of his articles on grape culture contributed to the Southern Agriculturist (1828) was reprinted as a pamphlet in 1833.[112] Perhaps for this reason in part, and perhaps too because he worked in the relative obscurity of the new, raw town of Columbia, he did not achieve the same effect as Adlum; in every other respect he seems entitled to the same recognition as his better-known contemporary. One might fairly think of them as sharing a divided labor, the one appealing to the mid-Atlantic states and to the North, the other to the South.

The uncertainties of a cotton-based agriculture on exhausted soils and in competition with new lands to the west made the search for alternative crops a familiar business in the seaboard states of the South. Viticulture was a frequently suggested possibility, and, as we have seen, the legislatures of both Carolinas supported experiments that would, it was hoped, bring it into being. Herbemont had his own special ideas about the public usefulness of a winegrowing industry. He was frightened by the future of a South with a slave population whose occupation—cotton—was disappearing from the older regions. What would happen if the slave population continued to grow while the work for which it was destined continued to diminish? What was wanted was a new industry—winegrowing—and a new kind of labor—"suitable labourers from Europe."[113]

In 1827 Herbemont presented his ideas to the South Carolina senate in the form of a memorial urging that the state subsidize the emigration of "a number of vignerons from France, Italy, Germany and Switzerland" who could be established in small communities throughout the state to turn the unprofitable pine barrens and sand hills into rich vineyards. The idea is one familiar from the beginning of southern colonization, but this time, at least, Herbemont recognized that European practices could not be simply transferred unchanged to the United States: "Experience has shown, that the mode of cultivation must be very different here from what it is in Europe." Nevertheless, Europeans could be quickly taught, and would then form a source of labor fit to carry out the agricultural transformation of the state.

The senate received the memorial with murmurs of praise for the "unwearied perserverance, untiring industry, and botanical research of the memorialist," but noted with regret that the state of the treasury would not allow the scheme to be acted on.[114]

A comparable scheme had been submitted to the South Carolina legislature a few years earlier by two promoters named Antonio Della Torre and James C. W. McDonnald. They proposed in 1825 to bring over Italian farmers—"a well conducted free white body of labourers"—to introduce the cultivation of that classic triad in the dream of American prosperity, wine, silk, and oil. Forty thousand dollars, they thought, would be enough to meet expenses through the necessary waiting time before profits started to roll in. Except that the language of their memorial is in a later idiom, one might be reading a prospectus of the sixteenth century—with the difference that the nineteenth-century visionaries were aware of earlier failures. These, however, were easily explained away, and appeal made to the unanswerable evidence of the native vine: "Your memorialists . . . feel assured also that the Great Author of nature would not have caused festoons of the wild grape to adorn many parts of this state, if He intended to declare—'this shall not be a wine country.'"[115] To this theological argument the legislature was politely respectful, but it did not see fit to support the faith with $40,000.

In Georgia, too, winemaking was thought of as a possible way out of agricultural depression. The committee on agriculture of the Georgia legislature reported in 1828 that the desirable commodities of which there was hope were—wine, silk, and oil! The persistence of the original vision, intact, after all the years since the colony's founding says much about the power of the wish over experience. But the committee had, it said, evidence that "very good wine was made in the state as early as 1740."[116] Is it possible that the evidence was that pathetic single bottle of Savannah wine presented to Oglethorpe by Stephens (see above, p. 51)?

Any genuine evidence in favor of the practicability of winegrowing in Georgia would have come from the examples of enthusiastic amateurs. The best known was General Thomas McCall, who, since 1816, had been tending a vineyard on piney land in Laurens County and making wine in small commercial quantities. His experience, which recapitulates the general American pattern, is interesting partly because it went back so far. McCall had known Andrew Estave, the Frenchman who directed the luckless public vineyard at Williamsburg in the early 1770s; McCall also read and made use of St. Pierre's Art of Planting and Cultivating the Vine .[117] He thus bridges the gap between the unbroken failures of prerevolutionary efforts and the tentative successes of the early nineteenth century. McCall, like everyone else, first planted vinifera grapes; when they failed, he fell back upon native vines, particularly one he called Warrenton, now identified as Herbemont. From a local fox grape he also made a wine with the delightful name of "Blue Favorite."[118] McCall had a technician's turn of mind: he kept careful notes on weather and on his wine-making procedures, and contributed an essential improvement to technique by making use, for the first time in the American record at any rate, of a hydrometer to

measure sugar content and so make possible accurate adjustment of the must.[119] This was a great and necessary development if well-balanced, light, dry table wines were ever to displace the over-sugared, brandy-bolstered confections that appear to have been the standard of such wine as Americans had contrived to make. The reputation of McCall's wines was such that the governor, in his message to the legislature in 1827, proposed that the state subsidize their production as a basis for a larger industry.[120] When he began his efforts, McCall said, he had for many years been unable to make "a single convert to the faith . . . they call me a visionary, and other names, as a reward for my endeavours."'[121] In time, he succeeded in interesting other amateurs to dabble in winemaking, and there was a period in the 1820s and early 1830s when Georgian connoisseurs were beginning to talk boastfully about the select vintages of their state. The impulse died with the individuals who imparted it, however; another generation would pass before anything resembling a continuing industry arose.

In 1830, at Philadelphia, the eccentric and unfortunate botanist and savant-of-all-trades, Constantine Rafinesque, born in Constantinople, but long resident in the United States, published the second volume of his Medical flora , a comprehensive treatise on the plants of North America having pharmaceutical value. Rafinesque, an original but undisciplined observer, who died in obscure poverty in the next decade, and whose classifications are the despair of later students, included in his work a long treatise on Vitis , with special reference to American vines and American conditions. He had, he tells us, worked in the vineyards of Adlum at Georgetown in preparation for his opus,[122] and he evidently thought highly enough of the sixty-odd pages that he devoted to the subject in his comprehensive treatise to republish them separately in the same year under the title of an American Manual of Grape Vines and the Method of Making Wine . Though his classifications are fanciful, and his advice on winemaking of no particular originality, Rafinesque obviously cared much about the possibilities of winegrowing in this country, and took the trouble to survey the state of the industry not once but twice, first in 1825 and again in 1830.[123] It is this information that still gives his curious treatise some authority after a century and a half have lapsed.

Dufour, we remember, had surveyed American grape growing at the end of the eighteenth century, and had found scarcely a single vineyard worthy of the name from New York to St. Louis. The changes made in the next quarter of a century are indicated by Rafinesque's summary. In 1825, he learned, there were not more than sixty vineyards to be found in the entire country, ranging from one to twenty acres, and aggregating not more than six hundred acres altogether. That was just after Adlum's introduction of the Catawba, the plantings of the Dutchmen around York, and the experiments of McCall, Herbemont, and others in the South; their contributions had not yet had their chance to take effect. Five years later, in 1830, Rafinesque found that the pace of things had accelerated in unmistakable fashion. There were then, he reported, two hundred vineyards of from three to forty acres, making a total of five thousand acres—a miniscule amount measured

37

Among his many interests, the unfortunate Constantine

Rafinesque (1783-1840) paid special attention to grapes

and wine. He worked in John Adlum's vineyard to gain

experience, published an American Manual of Grape

Vines and the Method of Making Wine , and made two

surveys of American winegrowing activity. Rafinesque was

an inveterate traveller and writer. His main work was in

botany and ichthyology, but he taught modern languages,

worked as a merchant, and wrote on banking, economics,

and the Bible before his death as a neglected pauper. (From

Rafinesque, "A Life of Travels," Chronica Botanica 8, no. 2 [1944])

against the undeveloped expanses of the United States, but still an impressive increase in a mere five years, testifying to a new confidence and a new sort of success in viticulture, so long attempted and so long frustrated in this country. Approximate and even doubtful as Rafinesque's figures are, they are at least symbolically valid as an expression of what was happening at last in the first part of the nineteenth century. As an act of piety towards the pioneers, Rafinesque set down the names of the vineyardists who had done the work: in New York, Gibbs, Prince, and Loubat; in Pennsylvania, Legaux, Eichelberger, Carr, Webb; in Maryland, Adlum; in Virginia, Lockhart, Weir, and Noel. The list goes on and does not bear quoting in full. But it marks the first time that such a thing could have been compiled, and for us it marks the point from which the growth of an industry can be measured. There have been many changes, diversions, obstructions, and failures since Rafinesque compiled his list, but there has not, since then, been any further doubt that the work of winegrowing in this country was a permanent fact rather than a prophecy—at least so far as nature's assent is concerned.