The Royal Society of Arts Competition

Across the river from Philadelphia, in the province of New Jersey, two other notable efforts at winegrowing were also begun before the Revolution. In 1758 the then newly founded London Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce offered a premium of £ 100 to the first colonist to produce five tuns of red or white wine of acceptable quality from grapes grown in the colonies (a tun equals 252 gallons). The prize offer was renewed until 1765, but no winner appeared, and it was then dropped.[29] Meantime, the gentlemen of the society had reconsidered the question and had sensibly concluded that good vineyards must precede good wine. It is possible that Franklin had something to do with this commonsense conclusion: he had become a member of the society in 1759, shortly after his arrival in London, and he was active in it thereafter.[30] He presided, for example, over the meeting of the society in 1761 at which it was resolved to commission the famous Philip Miller, of the Chelsea Botanical Garden, to write a treatise on viticulture expressly for the American colonies (just the sort of thing that Franklin would encourage), though Miller did not in fact produce one.[31]

In any case, in 1762 the society offered a premium of £ 200 for the largest vineyard of wine grapes, of no fewer than 500 vines, to be planted by 1767 in the colonies north of the Delaware, and another of equal value for one in the colonies south of the river. Second prizes of £ 50 each were also assigned to each region. This challenge called forth a successful response, the first prize being awarded to Edward Antill (1701-70), a country gentleman then living at Raritan Landing, near New Brunswick, New Jersey.[32] Like other experimental vineyardists in America, then and now, Antill was animated not merely by the hope of financial gain but by the enthusiast's wish to make the country abound in vines and wine. People laughed at

24

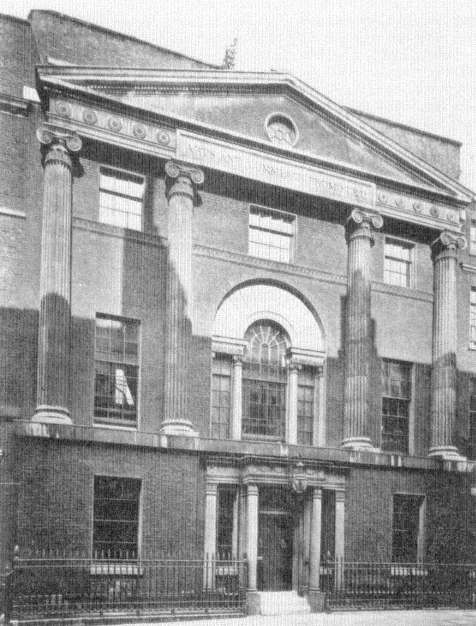

The Adam brothers' building for the Royal Society of Arts, John Street, London. Through its

competitions for colonial American vineyards from 1758 to the Revolution, the society did much

to establish the idea that American viticulture would be based on native American grapes.

(From London County Council, Survey of London , vol. 18 [1937])

his vineyard, Antill wrote in 1765 ("I have been thought by some Gentlemen as well as by Farmers, very whimsical in attempting a Vineyard"),[33] but he could not believe that nature could be opposed to it—"as if America alone was to be denied those cheering comforts which Nature with bountiful hand stretches forth to the rest of the world."[34]

The records of the society (now the Royal Society of Arts) preserve Antill's correspondence and allow us to see his vineyard in greater detail than any other in early America. He began planting French and Italian vines in 1764, on the south side of a hill facing a public road so that his experiment could be advertised to the skeptics. He also offered cuttings and instruction to those who showed an interest; it was the same missionary zeal that led him to compose what is now identified as the first specifically American treatise on viticulture. This work entitled "An Essay on the Cultivation of the Vine, and the Making of Wine, Suited to the Different Climates in North-America," was submitted to the American Philosophical Society in June of 1769 but not published until 1771, the year after Antill's death, when it was published in the Transactions of the society, whose original purpose, as expressed by Ben Franklin in 1743, included the "improvements of vegetable juices, as ciders, wines, etc."[35] The American spirit of improvement with which Antill wrote is nicely expressed at the beginning of his "Essay":

I know full well that this undertaking being new to my countrymen, the people of America, will meet many discouraging fears and apprehensions, lest it may not succeed. The fear of being pointed at or ridiculed, will hinder many: The apprehension of being at a certain expence, without the experience of a certain return, will hinder more from making the attempt; but let not these thoughts trouble you, nor make you afraid.[36]

Antill's knowledge that anyone trying to grow European grapes would be laughed at—we recall that Bolling in Virginia complained of the "little Heroes" who ridiculed his activity—shows that by this time in colonial history the question was firmly settled in the popular mind: European grapes would not grow here.

Antill heavily favored the European vine, and though he was keenly aware of the ignorance that hedged in all his experiments, he writes as though he already had a clear idea of the qualities of the available European varieties in this country. For a "fine rhenish," he wrote a correspondent in 1768, there were the white muscadine and others; some of the "best white wine" came from the Melie blanc; the "black Orleans" and the "blue Cluster" were the "best and true burgundy," and so on.[37] Despite the very positive recommendations, these were necessarily the expressions of hope rather than the record of experience. Antill did not wholly disregard the native grape: indeed, he said that he had collected "the best sort of native vines of America by way of trial."[38] But he did not live long enough to carry out extended trials of his native grapes, and he expressed doubt about them in his "Essay on the Cultivation of the Vine": "They will," he thought, "undergo a hard struggle indeed, before they will submit to a low and humble state."[39]

By 1765 Antill had 800 vines and a nursery. According to the certificate attesting his claim to the Society of Arts' £ 200 premium, the vines were planted six feet apart in the rows and the rows separated by five feet; the whole was fenced and well cultivated.[40] No one knew better than Antill how much had yet to be learned, and he clearly saw the need for systematic and cooperative work if the colonies were to achieve a successful viticulture; he wrote his "Essay" partly to stimulate such response. He urged the Society of Arts to publish a cheap guide to viticulture for use in America, where experience was lacking and where books were few and expensive.[41] He also proposed in 1768 that the colonies establish a public vineyard by subscription[42] —indeed, Leacock's plan for such a vineyard in 1773 was in acknowledged imitation of Antill's earlier plan: neither came to anything, though in the middle of the nineteenth century there was a public vineyard in Washington, D.C., a belated realization of an early idea.

Though Antill took the prize for a colonial vineyard, he had close competition from William Alexander (1726-83), commonly styled Lord Stirling on account of his claim (never officially allowed) to the lapsed earldom of Stirling. Alexander had imported vines and planted them in vineyards in New York and New Jersey as early as 1763;[43] he did so with a keen sense of the uncertainties of the enterprise: "Of all the vines of Europe, we do not yet know which of them will suit this climate; and until that is ascertained by experiment, our people will not plant vineyards; few of us are able, and a much less number willing, to make the experiment."[44] By 1767 Alexander had 2,100 vines planted at his estate of Basking Ridge, Somerset County, New Jersey, and claimed the society's premium of £ 200; according to the document presented to the society, the vines were "chiefly Burgundy, Orleans, Black, White and Red Frontiniac, Muscadine, Portugals and Tokays."[45] The rival claims of Alexander and of Antill evidently caused a quarrel within the society, for though the responsible committee adjudged the prize to Alexander, the society as a whole disagreed: the first prize went to Antill for his smaller vineyard; the second prize was not awarded; and a special gold medal went to Alexander.[46]

Antill's original vineyard cannot have survived very long, for Antill seems to have sold his place in 1768, a year after he had won his prize for his work. By 1783, according to the report of the German traveller Johann David Schoepf, Antill's negligent heirs had let the vineyard "fall into decay, because it demanded too much work";[47] it does not figure in the list of vineyards systematically visited in 1796 by John James Dufour. Yet Antill's experiments succeeded in stirring up some interest in viticulture among his neighbors. In 1806, long after Antill's death, S. W. Johnson of New Brunswick published a treatise on the cultivation of the vine in which he shows himself familiar with Antill's example. From it we learn that the vineyard planted by Antill had been restored by the current owner of the estate, Miles Smith, who cultivated there a number of vinifera varieties. Johnson named two or three other vineyardists in New Jersey, who "do honour to the state" and who may also be counted as heirs to Antill's work.[48]

As for Alexander's vineyard, it is not likely to have survived the death of its

proprietor in 1783. On the outbreak of the Revolution, Alexander went on active service in the patriot cause and served with distinction as a general officer until his death at Albany. Like Washington, he had no time to pursue the planter's activities that he preferred, and he did not again reside at Basking Ridge; within a few years of his death the estate was described as derelict.[49]

The London society did not score any obvious triumph in the colonies, but it did contribute to a development of lasting importance to American winegrowing by helping to turn attention to the native grape varieties. Taking a retrospective view of the New Jersey experiments of Alexander and Antill, the secretary of the society concluded that the chances of vinifera were doubtful: "but the society's measures," he added, "have occasioned trials of the native vines of America, which were before only considered as wild useless plants, that promise much better success."[50] In consequence, the society offered a new gold medal in 1768, this time for a vineyard of no fewer than 2,000 plants of the "indiginous native vines."[51] The medal was still among the society's list of awards in 1775, and, although in the next year the Revolution put an end to such encouragements from mother country to colony, the public announcement in favor of native vines perhaps had some effect—the society's offers and the policy behind them were evidently carefully watched by influential colonists. By this point in the baffling search for an American wine, the conviction at last seemed to be growing that a practical basis could be found only in the native plant.

The observation that American viticulture would be based on American varieties was, of course, as old as the attempt to grow grapes in the New World, or, more precisely, as old as the discovery that native grapes grew in North America. Thomas Harriot's Briefe and True Report of 1588 had prophesied that when the native grapes were "planted and husbanded as they should be, an important commodity in wines can be established."[52] Robert Johnson, in his Nova Britannia of 1609, affirmed that the colonists of Virginia, "by replanting and making tame the vines that naturally grow there" would soon make good wine;[53] Lord De La Warr in 1610 was confident that the "naturall vines" would, once they had been tamed and trained, yield "a perfect grape and fruitfull vintage."[54] The same vision had appeared to many another speculative pioneer on looking at the abundant and rudely flourishing vines of the uncleared woods. Sir William Berkeley is reported to have successfully cultivated the wild grapes of Virginia for winemaking before his death in 1677. William Penn, in 1683, had thoughts of domesticating the native grape; Sir Nathaniel Johnson had evidently made the effort in South Carolina in the first decade of the eighteenth century, as did Robert Beverley in Virginia.[55] Other instances of such early interest in sticking to the native varieties might be named, and I dwell on the point at such length because it is often said in print that nobody gave any thought to the native varieties until many, many years after the original settlements had been made. That is clearly not true. Yet it/s true that nobody had the patience, or the good luck, or the faith, to carry out the necessary labor, or to hit the right conditions, or to endure the uncertain waiting. More to the point, no one

knew what to do. The science of controlled plant hybridizing was still in the future, and though hybrids were no doubt naturally generated, they were random and unnoticed. It was only a stroke of luck that, at last, brought the Alexander to notice and pointed a way to the future; for many years to come all hybrids introduced for winegrowing were to be equally accidental and equally misunderstood, more often than not being identified as vinifera.

Under the circumstances, one need not wonder at the long time it took for the Americans to give up on vinifera after repeated, unvarying failure, decade after decade, in place after place. They had nothing else to turn to, really. Hardly any unameliorated variety of the native grape makes a tolerable, let alone satisfactory, wine by itself; the causes of the failure of vinifera were not understood and so could be denied by wishful thinking; and the qualities of the European vine were known. The wine from its grapes was familiar and good. For all these reasons it was inevitable that the fruitless experiment of growing vinifera should be stubbornly persisted in. By the end of the eighteenth century, however, the wish to have such wine as one gets from vinifera seems finally to have been yielding to the perception that Americans, if they were to make any wine of their own at all, would perforce have to invent their own grapes. That was the turning point, going back to the accidental discovery of the Alexander. One authority has observed that the eighteenth century in America was, in agricultural matters, a period of "singular lethargy," so that the "agricultural legacy of the colonies to the states was scant and of little worth."[56] But the introduction of the native hybrid grape makes a significant exception to that general proposition. After the Revolution, the important history of American wine in the eastern settlements is the history of experiment with native grapes.