4

Other Colonies and Communities Before the Revolution

Maryland and Pennsylvania: the Discovery of the Alexander Grape

The sort of experimental winegrowing illustrated by the Virginia planters just before the Revolution may be taken as general throughout those parts of the colonies where there was any tradition at all of hopeful attempt. Nor were such trials limited to the familiar places. In the exotic territory of Louisiana an Englishman, Colonel Ball, who settled some miles north of New Orleans on the banks of the Mississippi, managed to produce enough wine to send a sample of Louisiana claret or burgundy to King George III in 1775. The Indians put an end to this enterprise by massacring the colonel and his family. [1]

Back in the more settled regions of tidewater, Governor Horatio Sharpe informed Lord Baltimore in 1767 that he was hoping to improve and soften the native grape by cultivation. [2] He evidently favored the European grape, though, and other Marylanders agreed: Charles Carroll of Annapolis planted a vineyard in Howard County in 1770 with four sorts of vines that he called "Rhenish, Virginia grape, Claret and Burgundy." [3] After his death the vineyard was kept up by his son, the famous Charles Carroll of Carrollton, and it was still extant in 1796, making it the longest-lived of recorded colonial vineyards. [4] By that time, however, all but the native vines were reported to be dead. Growers nevertheless continued to try vinifera, as is shown by the newspaper advertisements of Maryland nurserymen

22

The Alexander grape, a spontaneous hybrid of vinifera and labrusca vines from which the first

commercial wines in America were made, was discovered around 1740 by James Alexander in

the neighborhood of Springettsbury, just above the northwest corner of Philadelphia, as shown

in this map of 1777. This was where William Penn's gardener had planted cuttings of vinifera in

1683. It is probable, then, that Penn's imported European vines had entered into the formation

of America's first wine grape by pollinating a native vine. (Detail of William Faden's map of

Philadelphia and environs; Map Division, Library of Congress)

right down to the Revolution offering European vines to be sold and planted in Maryland. [5]

Some time before the experiments of Carroll and Sharpe, an event of crucial significance had already occurred in Maryland when, in 1755 or 1756 (the second date is the more likely), Colonel Benjamin Tasker, Jr., a famous horseman and secretary to the province of Maryland, planted a two-acre vineyard at his sister's estate of Belair, in Prince Georges County, about twelve miles from Annapolis. [6] What was of immense, if unrecognized, significance in the colonel's modest enterprise was the grape he planted, called the Alexander. This, a cross between an unidentified native and a vinifera vine, is the earliest named hybrid of which we have record. According to the account given by William Bartram, the vine was discov-

ered around 1740 by James Alexander, then gardener to Thomas Penn, a son of William Penn. Alexander found the vine growing in the woods along the Schuylkill near the old vineyard established in 1683 by Andrew Doz for William Penn. [7] It is thus almost certainly a hybrid of one of Penn's European vines, and so Penn's ideas about refining the native grape were in fact realized, though by pure accident and long after his death.

Colonel Tasker succeeded in making wine of his grape, wine that quickly acquired some celebrity. On his travels through the colonies, the Reverend Andrew Burnaby had it served to him at the table of the governor of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and approved it as "not bad." [8] A more damaging description than Burnaby's faint praise is given by Governor Horatio Sharpe of Maryland, who, in response to the contemporary Lord Baltimore's request for some Maryland "Burgundy" to be shipped to him, had to reply that

There hath been no Burgundy made in Maryland since my arrival except two or three hogsheads which Col. Tasker made in 1759; this was much admired by all that tasted it in the months of February and March following, but in a week or two afterwards it lost both its colour and flavour so that no person would touch it and the ensuing winter being a severe one destroyed almost all the vines. [9]

Sad to say, the death of Colonel Tasker's vines in 1760 was followed, in the same year, by the death of the colonel himself at the early age of forty; like every other hopeful beginning of the sort of which we know anything, Tasker's flickered out quickly. In this case, though, there was a crucial difference: the hybrid grape had appeared, though how it travelled from Philadelphia to Maryland remains a subject for pure guessing. [10] The Alexander itself would persist well after Tasker, and, more important, was but the first of a list of American hybrids now grown to thousands and thousands.

Across the newly surveyed Mason-Dixon line to the north of Maryland, the scene in Pennsylvania and New Jersey in the years just before the Revolution resembled that in Virginia. The persistence of indomitably optimistic men had begun to have its effect: there was growing interest in, growing discussion of, and growing experiment with the wine vine that would in all probability have led to substantial results but for the interruption made by the Revolution.

One reason to think so was the presence in Pennsylvania of a great number of Germans who sorely missed the vine they had left behind. As the traveller Gottlieb Mittelberger reported in the 1750s, the Germans in America, especially the Würt-tembergers and the Rhinelanders, missed "the noble juice of the grape." Mittelberger saw that the conditions of sparse settlement, difficult transportation, and undeveloped markets would not soon be overcome; successful cultivation of the grape would not come all at once or soon, but, he wrote, "I have no doubt that in time, this too will come." [11]

In Pennsylvania it is, predictably, Ben Franklin who stands out among the proponents of winegrowing. No man has expressed the beneficent character of wine

better than Franklin did in his well-known affirmation that "God loves to see us happy, and therefore He gave us wine." [12] From the earliest moment at which he had access to the public ear, Franklin began giving instruction to his fellow-colonists about winemaking. Poor Richard's Almanack for 1743 contains directions for making wine offered to the "Friendly Reader" because, Poor Richard says, "I would have every Man take Advantage of the Blessings of Providence and few are acquainted with the Method of making Wine of the Grapes which grow wild in our Woods." Franklin's methods required the grapes to be trodden by foot—"get into the Hogshead bare-leg'd"—and specify a long cool fermentation lasting until Christmas. The casual freedom of those unregulated days appears strikingly in this word of advice: "If you make Wine for Sale, or to go beyond Sea, one quarter part must be distill'd, and the Brandy put into the three Quarters remaining." But of course where no industry existed, the tax-gatherer was not interested; and so one might distill and sell at retail without licenses, fears, or fees. As his last word, Franklin adds a modest disclaimer: "These Directions are not design'd for those who are skill'd in making Wine, but for those who have hitherto had no Acquaintance with that Art." [13]

In 1765, long after he had ceased to edit Poor Richard , and while he was acting as Pennsylvania's agent in London, Franklin took the trouble to adapt and publish for American readers of Poor Richard the directions drawn up by Aaron Hill for producing native wine; [14] not very authentic directions, perhaps, but who could know that? The immediate impulse behind Franklin's instructing the Americans in winemaking was probably the Sugar Act of 1764; this laid a duty for the first time on the Portuguese wines—Madeira included—that the colonists by long habit had regarded as immune from all duties. As one of Franklin's friends said on that melancholy occasion, "We must then drink wine of our own making or none at all." [15]

But Franklin did not need so drastic a reason to be active in favor of American wine. In the years before and after 1765 he had been busily encouraging the development of native wines. One anecdote told by the Boston merchant and judge Edmund Quincy is illustrative. Sometime—perhaps in the 1750s—Quincy met Franklin when the latter was on a visit to Boston, and heard Franklin say that the "Rhenish grape Vines" had lately been planted in Philadelphia with good success. Quincy remarked that he would like to have some for his Massachusetts garden, and thought nothing more of the matter until, some weeks later, he received cuttings of such vines in two parcels, one sent by water and one by land. On later meeting Franklin, Quincy learned that Franklin had not only taken the unasked trouble and expense of sending the vines but had had to obtain them some seventy miles from Philadelphia, his information about their growing in the city being mistaken. The young John Adams, who records the story, sums it up as an instance of Franklin's benevolence: all his trouble was "purely for the sake of doing good in the world by propagating the Rhenish wines thro these provinces. And Mr. Quincy has some of them now growing in his garden." [16] In 1761 Franklin wrote to Quincy wishing him "success in your attempts to make wine from American grapes," but

whether "American grapes" means simply any grapes grown in America, or that Quincy had abandoned his Rhenish grapes for natives we cannot know. [17] Terminology was so loose in those days that one can never be sure.

A rising expectation that wine could be grown in America characterized the last few years before the Revolution; it has an interesting echo in a proposal made to Franklin in 1772. He was then in London, representing not only Pennsylvania but Georgia, New Jersey, and Massachusetts as well; he was thus the man of preeminent authority and influence in all matters affecting the political and economic life of the colonies. If a projector or speculator had a notion for getting rich in the colonies, Franklin was obviously the man he would want to make sure of. One such ambitious person was the flamboyant Thomas O'Gorman, an Irish adventurer turned respectable Burgundian winegrower (as the fortunes of the Hennessys, Bartons, Lynches, and others suggest, there seems to be some secret affinity between the Irish and the French wine trade—some maintain that even Haut Brion is really O'Brien frenchified). O'Gorman, after serving with the French armies against the English, was made a chevalier, and, thanks to his Irish good looks, married a sister of that strange Chevalier D'Eon who lived sometimes as a man and sometimes as a woman. The marriage brought O'Gorman a large dowry in the form of Burgundian vineyards, which supported him until the French Revolution at last sent him back to Ireland. Long before that, however, in 1772, the rumors of the prospects of winegrowing in the colonies had somehow reached the chevalier, and he came forward with the plan of a winegrowing scheme in the colonies for which he tried to get Franklin's support. The key question was obtaining a parliamentary subsidy; in the vexed state of relations between England and her colonies that, however, was out of the question. Franklin recommended the chevalier to apply to the promoters of a new American colony in the Ohio lands, but their scheme soon collapsed, though not before Franklin had received a gift of wine from O'Gorman's Burgundian estate, vintage 1772: "a Hogshead of the right sort for you," as the chevalier described it. [18]

An even more interesting gift of wine was received by Franklin from a Pennsylvania Quaker named Thomas Livezey, who operated a mill on the Wissahickon near Philadelphia. In June 1767 Livezey sent to England a dozen bottles of American wine that he had made "from our small wild grape, which grows in great plenty in our woodland"; another dozen followed later in the year. "I heartily wish it may arrive safe," Livezey wrote, "and warm the hearts of everyone who tastes it, with a love for America." [19] It may only have been Franklin's diplomatic tact, but in thanking Livezey he affirmed that the wine "has been found excellent by many good judges," and in particular by Franklin's London wine merchant, who was "very desirous of knowing what quantity of it might be had and at what price." [20] One wonders whether Philip Mazzei was one of the judges to whom this American wine was submitted, and whether it had anything to do with his decision to try winegrowing in America? Livezey continued to make wine along the banks of the Wissahickon; tradition says that he sank several barrels of it in the stream to keep

23

Lottery tickets for John Leacock's scheme of a "public vineyard" in Philadelphia, 1773.

The lottery did not succeed, but a "public vineyard" was at last established by the federal

government at Washington, D.C., in 1858. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

it safe during the Revolution, and that one or two bottles of the wine thus preserved were still extant in the twentieth century. [21]

Another Philadelphian, the naturalist and traveller John Bartram, was thinking about winemaking in this decade. After his journey of botanical exploration through the South in 1765, Bartram wrote to the Reverend Jared Eliot, the pioneer American agricultural writer, that he had found a promising grape (probably a muscadine) in Carolina and hoped to be able to propagate it and others in sufficient quantity to furnish a winemaking industry. Bartram's motive was the cause of temperance: most Americans being "eager after strong liquors and spirits," wine was a highly desirable alternative. [22] The argument is so familiar in the history of this subject that one is compelled to accept the conclusion that Americans, especially in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, were formidable drinkers. What success Bartram had we do not know. About twenty years later, Johann Schoepf wrote that many sorts of American vines, collected by the elder Bartram, could be seen in Bartram's Gardens in Philadelphia, then conducted by William, the son. Schoepf reported that the grapes improved under cultivation, a frequently met assertion much easier to make than to prove. [23]

Winegrowing was evidently much in the air around Philadelphia at the end of the 1760s. Samples of wine from native grapes, produced by R. S. Jones, by Dr. Francis Alison, and by Dr. Philip Syng, were exhibited at the American Philosophical Society in 1768. [24] In the same year John Leacock, a retired Philadelphia

silversmith, and later the author of patriotic dramas, began planting for himself and other interested experimenters at his farm in Lower Merion Township "white, blue, and purple grapes, as well as Lisbon and Muscadine vines."[25] Some of these Leacock received from other local growers, some were from foreign sources. At the end of 1772 he was encouraged enough to inform the American Philosophical Society that he meant to undertake a public vineyard "for the good of all the Provinces, from which might be drawn such vines or cuttings free of all expence, as might best suit each province."[26] To finance this philanthropic project, Leacock proposed a public lottery—then a popular and legal form of money-raising in Pennsylvania—and actually issued tickets in 1773 for his "Public Vineyard Cash Lottery." By 1775 Leacock had experience enough of the afflictions that ravaged his vinifera vines—rot, insects, and weather—to wonder whether native vines might not be the answer.[27] But, as with so many other efforts at this time, the Revolution put an end to Leacock's work. He left his farm in 1777 in advance of the British occupation of Philadelphia, and does not seem ever to have returned to it.[28]

The Royal Society of Arts Competition

Across the river from Philadelphia, in the province of New Jersey, two other notable efforts at winegrowing were also begun before the Revolution. In 1758 the then newly founded London Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce offered a premium of £ 100 to the first colonist to produce five tuns of red or white wine of acceptable quality from grapes grown in the colonies (a tun equals 252 gallons). The prize offer was renewed until 1765, but no winner appeared, and it was then dropped.[29] Meantime, the gentlemen of the society had reconsidered the question and had sensibly concluded that good vineyards must precede good wine. It is possible that Franklin had something to do with this commonsense conclusion: he had become a member of the society in 1759, shortly after his arrival in London, and he was active in it thereafter.[30] He presided, for example, over the meeting of the society in 1761 at which it was resolved to commission the famous Philip Miller, of the Chelsea Botanical Garden, to write a treatise on viticulture expressly for the American colonies (just the sort of thing that Franklin would encourage), though Miller did not in fact produce one.[31]

In any case, in 1762 the society offered a premium of £ 200 for the largest vineyard of wine grapes, of no fewer than 500 vines, to be planted by 1767 in the colonies north of the Delaware, and another of equal value for one in the colonies south of the river. Second prizes of £ 50 each were also assigned to each region. This challenge called forth a successful response, the first prize being awarded to Edward Antill (1701-70), a country gentleman then living at Raritan Landing, near New Brunswick, New Jersey.[32] Like other experimental vineyardists in America, then and now, Antill was animated not merely by the hope of financial gain but by the enthusiast's wish to make the country abound in vines and wine. People laughed at

24

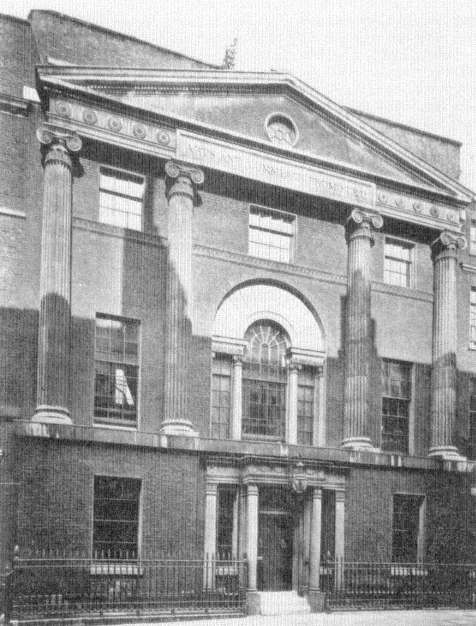

The Adam brothers' building for the Royal Society of Arts, John Street, London. Through its

competitions for colonial American vineyards from 1758 to the Revolution, the society did much

to establish the idea that American viticulture would be based on native American grapes.

(From London County Council, Survey of London , vol. 18 [1937])

his vineyard, Antill wrote in 1765 ("I have been thought by some Gentlemen as well as by Farmers, very whimsical in attempting a Vineyard"),[33] but he could not believe that nature could be opposed to it—"as if America alone was to be denied those cheering comforts which Nature with bountiful hand stretches forth to the rest of the world."[34]

The records of the society (now the Royal Society of Arts) preserve Antill's correspondence and allow us to see his vineyard in greater detail than any other in early America. He began planting French and Italian vines in 1764, on the south side of a hill facing a public road so that his experiment could be advertised to the skeptics. He also offered cuttings and instruction to those who showed an interest; it was the same missionary zeal that led him to compose what is now identified as the first specifically American treatise on viticulture. This work entitled "An Essay on the Cultivation of the Vine, and the Making of Wine, Suited to the Different Climates in North-America," was submitted to the American Philosophical Society in June of 1769 but not published until 1771, the year after Antill's death, when it was published in the Transactions of the society, whose original purpose, as expressed by Ben Franklin in 1743, included the "improvements of vegetable juices, as ciders, wines, etc."[35] The American spirit of improvement with which Antill wrote is nicely expressed at the beginning of his "Essay":

I know full well that this undertaking being new to my countrymen, the people of America, will meet many discouraging fears and apprehensions, lest it may not succeed. The fear of being pointed at or ridiculed, will hinder many: The apprehension of being at a certain expence, without the experience of a certain return, will hinder more from making the attempt; but let not these thoughts trouble you, nor make you afraid.[36]

Antill's knowledge that anyone trying to grow European grapes would be laughed at—we recall that Bolling in Virginia complained of the "little Heroes" who ridiculed his activity—shows that by this time in colonial history the question was firmly settled in the popular mind: European grapes would not grow here.

Antill heavily favored the European vine, and though he was keenly aware of the ignorance that hedged in all his experiments, he writes as though he already had a clear idea of the qualities of the available European varieties in this country. For a "fine rhenish," he wrote a correspondent in 1768, there were the white muscadine and others; some of the "best white wine" came from the Melie blanc; the "black Orleans" and the "blue Cluster" were the "best and true burgundy," and so on.[37] Despite the very positive recommendations, these were necessarily the expressions of hope rather than the record of experience. Antill did not wholly disregard the native grape: indeed, he said that he had collected "the best sort of native vines of America by way of trial."[38] But he did not live long enough to carry out extended trials of his native grapes, and he expressed doubt about them in his "Essay on the Cultivation of the Vine": "They will," he thought, "undergo a hard struggle indeed, before they will submit to a low and humble state."[39]

By 1765 Antill had 800 vines and a nursery. According to the certificate attesting his claim to the Society of Arts' £ 200 premium, the vines were planted six feet apart in the rows and the rows separated by five feet; the whole was fenced and well cultivated.[40] No one knew better than Antill how much had yet to be learned, and he clearly saw the need for systematic and cooperative work if the colonies were to achieve a successful viticulture; he wrote his "Essay" partly to stimulate such response. He urged the Society of Arts to publish a cheap guide to viticulture for use in America, where experience was lacking and where books were few and expensive.[41] He also proposed in 1768 that the colonies establish a public vineyard by subscription[42] —indeed, Leacock's plan for such a vineyard in 1773 was in acknowledged imitation of Antill's earlier plan: neither came to anything, though in the middle of the nineteenth century there was a public vineyard in Washington, D.C., a belated realization of an early idea.

Though Antill took the prize for a colonial vineyard, he had close competition from William Alexander (1726-83), commonly styled Lord Stirling on account of his claim (never officially allowed) to the lapsed earldom of Stirling. Alexander had imported vines and planted them in vineyards in New York and New Jersey as early as 1763;[43] he did so with a keen sense of the uncertainties of the enterprise: "Of all the vines of Europe, we do not yet know which of them will suit this climate; and until that is ascertained by experiment, our people will not plant vineyards; few of us are able, and a much less number willing, to make the experiment."[44] By 1767 Alexander had 2,100 vines planted at his estate of Basking Ridge, Somerset County, New Jersey, and claimed the society's premium of £ 200; according to the document presented to the society, the vines were "chiefly Burgundy, Orleans, Black, White and Red Frontiniac, Muscadine, Portugals and Tokays."[45] The rival claims of Alexander and of Antill evidently caused a quarrel within the society, for though the responsible committee adjudged the prize to Alexander, the society as a whole disagreed: the first prize went to Antill for his smaller vineyard; the second prize was not awarded; and a special gold medal went to Alexander.[46]

Antill's original vineyard cannot have survived very long, for Antill seems to have sold his place in 1768, a year after he had won his prize for his work. By 1783, according to the report of the German traveller Johann David Schoepf, Antill's negligent heirs had let the vineyard "fall into decay, because it demanded too much work";[47] it does not figure in the list of vineyards systematically visited in 1796 by John James Dufour. Yet Antill's experiments succeeded in stirring up some interest in viticulture among his neighbors. In 1806, long after Antill's death, S. W. Johnson of New Brunswick published a treatise on the cultivation of the vine in which he shows himself familiar with Antill's example. From it we learn that the vineyard planted by Antill had been restored by the current owner of the estate, Miles Smith, who cultivated there a number of vinifera varieties. Johnson named two or three other vineyardists in New Jersey, who "do honour to the state" and who may also be counted as heirs to Antill's work.[48]

As for Alexander's vineyard, it is not likely to have survived the death of its

proprietor in 1783. On the outbreak of the Revolution, Alexander went on active service in the patriot cause and served with distinction as a general officer until his death at Albany. Like Washington, he had no time to pursue the planter's activities that he preferred, and he did not again reside at Basking Ridge; within a few years of his death the estate was described as derelict.[49]

The London society did not score any obvious triumph in the colonies, but it did contribute to a development of lasting importance to American winegrowing by helping to turn attention to the native grape varieties. Taking a retrospective view of the New Jersey experiments of Alexander and Antill, the secretary of the society concluded that the chances of vinifera were doubtful: "but the society's measures," he added, "have occasioned trials of the native vines of America, which were before only considered as wild useless plants, that promise much better success."[50] In consequence, the society offered a new gold medal in 1768, this time for a vineyard of no fewer than 2,000 plants of the "indiginous native vines."[51] The medal was still among the society's list of awards in 1775, and, although in the next year the Revolution put an end to such encouragements from mother country to colony, the public announcement in favor of native vines perhaps had some effect—the society's offers and the policy behind them were evidently carefully watched by influential colonists. By this point in the baffling search for an American wine, the conviction at last seemed to be growing that a practical basis could be found only in the native plant.

The observation that American viticulture would be based on American varieties was, of course, as old as the attempt to grow grapes in the New World, or, more precisely, as old as the discovery that native grapes grew in North America. Thomas Harriot's Briefe and True Report of 1588 had prophesied that when the native grapes were "planted and husbanded as they should be, an important commodity in wines can be established."[52] Robert Johnson, in his Nova Britannia of 1609, affirmed that the colonists of Virginia, "by replanting and making tame the vines that naturally grow there" would soon make good wine;[53] Lord De La Warr in 1610 was confident that the "naturall vines" would, once they had been tamed and trained, yield "a perfect grape and fruitfull vintage."[54] The same vision had appeared to many another speculative pioneer on looking at the abundant and rudely flourishing vines of the uncleared woods. Sir William Berkeley is reported to have successfully cultivated the wild grapes of Virginia for winemaking before his death in 1677. William Penn, in 1683, had thoughts of domesticating the native grape; Sir Nathaniel Johnson had evidently made the effort in South Carolina in the first decade of the eighteenth century, as did Robert Beverley in Virginia.[55] Other instances of such early interest in sticking to the native varieties might be named, and I dwell on the point at such length because it is often said in print that nobody gave any thought to the native varieties until many, many years after the original settlements had been made. That is clearly not true. Yet it/s true that nobody had the patience, or the good luck, or the faith, to carry out the necessary labor, or to hit the right conditions, or to endure the uncertain waiting. More to the point, no one

knew what to do. The science of controlled plant hybridizing was still in the future, and though hybrids were no doubt naturally generated, they were random and unnoticed. It was only a stroke of luck that, at last, brought the Alexander to notice and pointed a way to the future; for many years to come all hybrids introduced for winegrowing were to be equally accidental and equally misunderstood, more often than not being identified as vinifera.

Under the circumstances, one need not wonder at the long time it took for the Americans to give up on vinifera after repeated, unvarying failure, decade after decade, in place after place. They had nothing else to turn to, really. Hardly any unameliorated variety of the native grape makes a tolerable, let alone satisfactory, wine by itself; the causes of the failure of vinifera were not understood and so could be denied by wishful thinking; and the qualities of the European vine were known. The wine from its grapes was familiar and good. For all these reasons it was inevitable that the fruitless experiment of growing vinifera should be stubbornly persisted in. By the end of the eighteenth century, however, the wish to have such wine as one gets from vinifera seems finally to have been yielding to the perception that Americans, if they were to make any wine of their own at all, would perforce have to invent their own grapes. That was the turning point, going back to the accidental discovery of the Alexander. One authority has observed that the eighteenth century in America was, in agricultural matters, a period of "singular lethargy," so that the "agricultural legacy of the colonies to the states was scant and of little worth."[56] But the introduction of the native hybrid grape makes a significant exception to that general proposition. After the Revolution, the important history of American wine in the eastern settlements is the history of experiment with native grapes.

The Contribution of Continental Emigrants: the Huguenots and St. Pierre

Many individuals of all European nations made their way to the English colonies of North America from the earliest days. In addition, there were many organized efforts—often for speculative rather than philanthropic purposes—to settle whole groups of non-English Protestant peoples to help develop the colonial economy. France, Switzerland, and the German-speaking territories were the prime sources, and more often than not it was winemaking, a work no Englishman was born to, that furnished the main object of such settlements. In this history, the French Huguenots come first.

The earliest group of Huguenot emigrés has already been mentioned, the group that was sent at the expense of King Charles II to South Carolina in 1680 to undertake "ye manufacture of silkes, oyles, wines, etc."[57] The forty-five persons. who came for that purpose seem to have been diverted to other work very quickly, and, as we know, no winegrowing tradition was ever established in Carolina. The

idea always persisted, though, and in the promotional literature attending any effort to bring over continental emigrés, the prospect of a flourishing viticulture was inevitably made one of the leading attractions. The settlement arranged by the Swiss promoter Jean Pierre Purry at Purrysburgh in South Carolina is an example. Beginning in 1724 Purry proposed various schemes to the British authorities to bring over large numbers of Swiss, including exiled Huguenots living in Switzerland. After some false starts, he succeeded in 1731 in bringing over a contingent of mixed French and Swiss Protestants, who were settled on land granted to Purry on the banks of the Savannah, not very many miles up the river from the spot that was to be the site of Oglethorpe's Savannah in 1733. The kind of blandishment by which Purry attracted his colonists appears in his tract entitled Proposals of Mr. Peter Purry, of Newfchatel, For Encouragement of Such Swiss Protestants as Should Agree to Accompany him to Carolina , published in 1731. "The woods are full of wild vines, bearing 5 or 6 sorts of grapes naturally," Purry wrote; for want of vine dressers, no wine but Madeira was drunk in South Carolina, and there, he suggested, lay the opportunity for the French and Swiss. They could take over from the Portuguese the lucrative task of supplying wine to the colony.[58] Purry's project was assisted by Governor Robert Johnson, who was interested in winegrowing for South Carolina (see above, p. 55). The contemporary reports of Purrysburgh make no mention of viticulture, however, and it seems safe to conclude that it was not even seriously begun, despite the expectations and the traditions of the Huguenots.

A third organized migration of Huguenots to South Carolina did make a determined effort to establish vineyards there. This was the community called New Bordeaux, whose origins may be traced to 1763, when some of the many Huguenots still living in London petitioned the Board of Trade for lands along the Savannah River, where they proposed "to apply themselves principally to the cultivation of vines and of silk."[59] The petition was favorably received, and in 1764 some 132 French Protestants were sent to land lying near the Savannah River on Long Cane Creek, many miles above the Purrysburgh settlement. There, amidst the 26,000 acres of their grant, the French laid out their town of New Bordeaux; as the still-surviving map of the original survey shows, of the 800 acres of the town tract, 175 acres were reserved, "to be divided into 4-acre lots for vineyards and olive gardens."[60] It may have been of these settlers' early efforts at winemaking that William Stork spoke in his Description of East Florida (1769), saying: "I have drank a red of the growth of that province [South Carolina] little inferior to Burgundy."[61]

Whatever effort they made towards developing their vineyards was powerfully reinforced in 1768, when the community was joined by another migration of French Protestants under the leadership of Louis de Mesnil de St. Pierre.[62] St. Pierre's original intention had been to take his people to Nova Scotia, but accident brought them to South Carolina instead. They could not have had viticulture in mind from the beginning: Nova Scotia was no place for the vine (though there are now vineyards and several small wineries there), and St. Pierre, a Norman, did not belong to the wine regions of France. Once in New Bordeaux, however, he devoted himself

to viticulture with a determined zeal. The land, he wrote enthusiastically, "rose into gentle declivities, interspersed with delightful vales of small extent": soil, water, climate, all were perfect for growing wine grapes, so that—the conclusion is painfully familiar—"we may venture to pronounce the success infallible."[63]

The immediate effect of St. Pierre's work was evident in the next year, when the colonists of New Bordeaux petitioned the colonial assembly for new vines and were granted ~700 for their purchase.[64] By 1771 St. Pierre had formed a plan to promote the cultivation of vines at New Bordeaux through an ambitious scheme of importing both cuttings and professional vignerons from Europe. St. Pierre first took his proposals to the governor and assembly of South Carolina for the necessary appropriation, and though a committee reported favorably and the assembly was sympathetic, he did not get his money. Nevertheless, he was already importing vines from Europe and planting them at New Bordeaux.[65]

His next step was to go to England to press his ideas upon the home authorities. According to his own report, St. Pierre took wine from South Carolina with him to London and submitted it to Lord Hillsborough, then secretary for the American colonies, but received no encouragement.[66] It was later said that Hillsborough was paid £ 250,000 by the French to dampen the enterprise, since the French were terrified lest South Carolina take away the American wine trade! How likely a story this is need not be argued.[67] St. Pierre had better success with the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, for those gentlemen in January 1772 awarded him a gold medal in recognition of his samples of wines, indigo, and silk.[68]

Though disappointed in his first effort to gain official support, St. Pierre was not a man to give up without a struggle; from the offices of the minister he appealed directly to the public by attempting to float a public subscription of £ 4,000 for the "Society for the Encouragement of the Culture of Vine Yards at New Bordeaux," which would undertake to plant not less than fifty acres of vines within three years.[69] A fellow South Carolinian, the retired merchant and statesman Henry Laurens, was then in London and had at first acted as St. Pierre's patron. When St. Pierre determined on his scheme of a public subscription, however, he and Laurens differed: Laurens refused to "subscribe Money in order to induce and lead on other People," and St. Pierre turned from him in anger.[70] Since Laurens, as we have seen, dreamed of a time when South Carolina's wines would float down its rivers to the markets of the world, his refusal to assist St. Pierre's speculation was obviously not that of a man ill-disposed to winegrowing. St. Pierre's enthusiasm evidently could not persuade the more experienced Laurens.

The public subscription failed, but St. Pierre kept up the fight. Some weeks afterwards he published a second proposal under the emphatic heading of The Great Utility of establishing the Culture of Vines . . . And the absolute Necessity of Supporting the Infant Colony of Wrench Protestants settled at New Bordeaux in South Carolina, who have brought the Culture of Vines, and the Art of raising Silk to Perfection .[71] This appeal assured the British public that it need not fear the same failure that had overtaken all other such ventures: the difference at New Bordeaux lay in the French—"At

25

Title page of Louis de Mesnil de St. Pierre's Art of Planting and Cultivating

the Vine (London, 1772). Published when St. Pierre was desperately working

to secure English support for the winegrowing colony of New Bordeaux, South

Carolina, the book assured the English that winegrowing was bound to succeed

in Carolina and that it could bring nothing but good to England. (California

State University, Fresno, Library)

New Bordeaux the Vine is taken care of, and properly cultivated, by Persons bred from their Cradles in Vineyards." He had sent 60,000 Burgundian vines to South Carolina since his first proposals were made, St. Pierre said, and had another 100,000 at his disposal, as well as a number of rigneron families ready to go.[72]

When the response to this offer was again unsatisfactory, St. Pierre turned back to the government, this time appealing to Parliament for a grant to pay for the expenses of shipping out his 100,000 plants and 150 new settlers, "all vignerons to a man." What he asked from Parliament was £ 4,200 at 5 percent interest for ten years, and that was but a part of the expense that he envisaged.[73] At the same time he addressed the Treasury, praying for "encouragement upon him and his infant colony." The Board of Trade endorsed St. Pierre's claim, saying that it "could not fail of being usefull to this kingdom," but these good words were all that St. Pierre got for his pains.[74] Or rather, almost all: he did receive a grant of 5,000 acres, an extraordinary grant to an individual at that time.

His energetic campaign against English pockets kept St. Pierre busy with his pen. Besides his two appeals to the public at large, his petition to Parliament, and various other supporting memorials and petitions to the Treasury and the Board of Trade, he produced for potential subscribers and emigrants alike an apology and a treatise combined, entitled The Art of Planting and Cultivating the Fine, as also of Making, Fining, and Preserving Wines, etc . (London, 1772). His strategy in the book is to stress the good that winegrowing in Carolina will create for England: it will divert the colonists away from competition with England's manufactures; it will improve the breed and increase the population—for "whence is France so fruitful in men, but by the use of the juice of the grape?"; by the trade in wine, British seamen and shipbuilders will gain employment, thereby improving the national defense as well; so, too, the employment created will prevent British workers from being lost to foreign parts. With all this to follow from planting vines at New Bordeaux, how could one hesitate? Especially when the flourishing of native vines gave "sure proof of the success of the present enterprise"?[75]

The part of St. Pierre's book given over to viticultural instruction follows European practices. Though St. Pierre says that he visited France for the purpose, and though he seems to have done a conscientious piece of homework, he is not aware of any inadequacy in stating, as he does, that "I have confined my researches to the three wine countries of Orleans, Champagne, and Burgundy."[76] The convergence of dates for the first three treatises by American winegrowers on viticulture—Antill's essay in 1771, St. Pierre's book in 1772, and Bolling's MS in 1774—is striking evidence of how interest in the subject was intensifying immediately before the Revolution. But it is also notable that all three of these take for granted that American viticulture will be founded on the European grape, and that no special reference to American conditions is therefore necessary. St. Pierre's book is now chiefly interesting for its expression of the author's entire confidence in what he is doing: winegrowing must succeed in America, St. Pierre insists, even though he cannot put much wine of his own making into evidence.

Neither the English government nor the English public came through for St.

Pierre, though it was said that King George requested him to carry on under the king's private patronage.[77] Somehow he managed to complete a part of his scheme. He returned to South Carolina at the end of 1772 with a group of vignerons recruited for his project. They had travelled by way of Madeira, where St. Pierre had acquired another large collection of vines. And at New Bordeaux they would have found things in flourishing condition, for we learn from a report written in June of 1772 that the vineyards already planted there were doing extremely well, so well that no one doubted of ultimate success. A shipment of European vines had also arrived in Charleston, the correspondent noted, where they had been set out to root and where, he added, people were stealing them, so popular was the idea of winegrowing.[78]

"My vineyard is thriving," St. Pierre wrote after his return to New Bordeaux: "Others beside mine are in perfect good order, and next year we shall have a good deal of wine as well as silk made here .... of all the vines planted last March, some of which I brought from Madeira, none have miscarried but are now in full growth."[79] Two, at least, of the "others" who were cultivating the vine at New Bordeaux may be identified. One was not a Frenchman but a neighboring German named Christopher Sherb, a native of the valley of the Neckar in Württemberg, who had planted a vineyard on his farm at Broad River, not far from New Bordeaux. Starting with a few cuttings of German vines obtained from settlers in Orangeburg, by 1770 he had a vineyard of 1,539 vines, including both vinifera and natives. The yield was tiny—25 gallons in 1768 and 80 gallons of "tolerable white wine" in 1769, good enough to be sold at a dollar a gallon and to win a £ 50 bounty from the always attentive London Society for the Encouragement of the Arts in 1770.[80] Sherb's example helped to confirm St. Pierre in his belief that South Carolina was a region destined for winemaking.

The other identifiable grower from the region of New Bordeaux was John Lewis Gervais (1741-95), a Frenchman of Huguenot origin who came to South Carolina in 1764. There he was befriended by Henry Laurens, always interested in viticulture in Carolina, who gave him land at New Bordeaux.[81] Gervais seems to have made vine plantings there for Laurens as well as for himself. When he was visited by the official surveyor to the English Board of Trade, John De Brahm, Gervais had his vines trained according to a method that De Brahm thought admirably adapted to the conditions of the South. The growers of New Bordeaux, De Brahm says, had discovered that

the grape vine needs no support, neither of sticks or frames, but prospers by being winded on the ground, and piled up in a manner, that the vine itself forms a kind of close bower, (or as the French call it a chapele) where, under it shades its own ground to retain all moisture, which also covers and preserves the blossom of the grapes against vernal Frost, and the grapes themselves against the violent scorching summer heat.[82]

Writing about 1771, De Brahm was not able to say anything about the wine of New Bordeaux. As usual in the colonial story, it was just around the corner: "As

for the goodness of the wine itself, its decovery [the discovery of its qualities?] may, without doubt be very shortly expected." So wrote De Brahm, who visited New Bordeaux and believed in its future; he thought that since South Carolina lay between 30 and 35 degrees of latitude, and since the Jesuit fathers were known to have produced wine in Mexico between 25 and 30 degrees of latitude for the refreshment of the Acapulco galleons, winegrowing must succeed in South Carolina.[83]

When William Bartram travelled through South Carolina in June 1775, he was entertained at St. Pierre's residence, Orange Hill, which stood on a hill looking out over the Savannah River and into Georgia, where winegrowing had been tried years before; Bartram found St. Pierre tending "a very thriving vineyard consisting of about five acres" at New Bordeaux.[84] Since St. Pierre had been there since 1768, he was one of the very few of colonial vineyardists who actually persisted long enough to have produced anything (Robert Beverley in Virginia and the Carrolls in Maryland were others). Whether he was as hopeful in 1775 as he had been at the beginning of the decade we do not know. Bartram says nothing about St. Pierre's wine, if there was any. In any case, the Revolution put an end to the enterprise. St. Pierre joined the South Carolinian patriots in the war and was, according to a contemporary note, made "Lieutenant to a Small Fort in the back Country where he lives upon his pay of £ 30-a year."[85] St. Pierre was killed on an expedition against the Indians, and that "untimely end," as a later memorialist wrote, "overturned the establishment in its infancy."[86] New Bordeaux itself, never very flourishing, dwindled to the crossroads that it now is, where a marker records the site of the old Huguenot church.

Other Huguenot Communities

To go back almost a hundred years, in 1685 a large migration of Protestants from France had taken place in response to the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, whereby Louis XIV suddenly withdrew from the Huguenots the legal protection that they had secured a century earlier. Though the French government tried to prevent a Huguenot emigration, thousands left the country. There was a general scramble among the proprietors and promoters of American colonies to attract these unlucky people, for they were intelligent, industrious, skilled, well-behaved, and right-thinking—the ideal colonists, in short, and very unlike the average of the marginal types who could be lured into the American backwoods. Landlords in Virginia, the Carolinas, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts all tried to put their attractions before various Huguenot communities. Virginia managed to secure some: as early as 1686 one Virginia promoter, with an eye upon the Huguenots, advertised his property in Stafford County as "naturally inclined to vines."[87] A Huguenot traveller, Durand de Dauphiné, visiting Stafford County the next year, was much struck by the promising terrain and by the wild vines there; he made, he says, some "good" wine from the grapes, and recommended them for cultivation.[88] His

account was published in Europe in 1687, but it apparently did not succeed in attracting any Huguenots and did not lead to any winegrowing development in Stafford County.

In 1700 a large body of Huguenots arrived in Virginia under the special auspices of King William and settled on a 10,000-acre tract along the James River donated by the colony. Here, at Manakin Town (near present-day Richmond) they had succeeded by 1702 in making a "claret" from native grapes that was reported to be "pleasant, strong, and full body'd wine."[89] The information, recorded by the historian and viticulturist Robert Beverley, was evidence to him that the native vines needed only to be properly cultivated to become the source of excellent wine and evidently had much to do in starting him on his own experiments. The opinion of Beverley is confirmed by the Swiss traveller Louis Michel, who visited Manakin Town in 1702 and was impressed by the incredibly large vines growing there, from which, he wrote, the French "make fairly good wine, a beginning has been made to graft them, the prospects are fine."[90] The prospects soon changed for the worse: according to the Carolina historian John Lawson, the French at Manakin Town found themselves hemmed in by other colonists, who took up all the land around them, and so most of them departed for Carolina, where their minister assured Lawson that "their intent was to propagate vines, as far as their present circumstances would permit, provided they could get any slips of vines, that would do."[91]

In Florida, at the same time that New Smyrna was being built in East Florida, the home government attempted to do something for unpopulated and unremunerative West Florida by sending over, in 1766, a band of forty-six French Protestants to pursue their arts of winemaking and silk producing. They were settled at a place called Campbell Town, east of Pensacola, but conditions there were so wild and unpromising that failure was quick and complete. The group was badly led, the incidence of disease was very high, and within four years all the French were either dead or had left the province.[92] This was, I think, the last instance in which London officials tried to create a colonial enterprise by the expedient of simply dumping a band of Huguenots upon the land, with most dire results for the poor Huguenots themselves.

Beyond the South, there were other, isolated Huguenot communities that attempted winegrowing. Those in Massachusetts and in Rhode Island have already' been mentioned. In Pennsylvania, the first winemaker whose name we know was the Huguenot Gabriel Rappel, whose "good claret" pleased William Penn in 1683; another of the earliest was Jacob Pellison, also a Huguenot, as was Andrew Doz, who planted and tended William Penn's vineyard of French vines at Lemon Hill on the Schuylkill.[93] Doz, naturalized in England in 1682, came over to Pennsylvania in that same year; Penn called him a "hot" man but honest.[94] The vineyard, which was begun in 1683, stood on 200 acres of land and was described in 1684 by the German Pastorius as a "fine vineyard of French vines." "Its growth," Pastorius added, "is a pleasure to behold and brought into my reflections, as I looked upon it, the fifteenth chapter of John."[95]

Two years later, another witness reported that "the Governours Vineyard goes on very well."[96] In 1690 the property was patented to Doz himself for a rental of 100 vine cuttings payable annually to Penn as proprietor.[97] From that arrangement it seems clear that the experiment of vine growing was still in process after its beginning seven years earlier. It would be interesting to know whether any of the European vines survived as late as that.

William Penn himself was particularly active in seeking to attract Huguenot emigrants to Pennsylvania, and used the prospect of viticulture as a recruiting inducement. His promotional tract of 1683, A Letter from William Penn . . . Containing a General Description of the Said Province , was translated into French and published at The Hague in order to reach the French Protestant community exiled in the Low Countries. In his new province, Penn wrote, were "grapes of diverse sorts" that "only want skilful Vinerons to make good use of them."[98] Penn's pamphlet, though written with an eye on prospective French colonists, is ostensibly addressed to the Free Society of Traders in Pennsylvania, incorporated by Penn in London; he concludes by telling this body that the great objects of the colony, the "Promotion of Wine" and the manufacture of linen, are likely to be best served by Frenchmen: "To that end, I would advise you to send for some thousands of plants out of France, with some Vinerons, and People of the other vocation."[99] Penn's efforts at recruiting had good results. Many religious refugees made their way to the colony, Huguenots among them; but the French were soon assimilated into the general community rather than maintaining a separate identity. They may have undertaken viticulture at first, but their dispersal through the community meant that those who persisted at it did so as individuals. As Penn told the Board of Trade in 1697, in Pennsylvania "both Germans and French make wine yearly, white and red, but not in quantity for export."[100]

The best known of Huguenot settlements in America are those of New York State, at New Paltz and New Rochelle, the one going back to the mid seventeenth century, the other founded towards the end of it. In neither does there seem to have been any attempt at winegrowing, despite the likelihood of their sites and the practice of the neighboring colonies in Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

The Contribution of Continental Emigrants: the Germans

After the Huguenots, the continental emigrants most often associated with experimental viticulture in America were German-speaking Protestants of the many varieties native to Switzerland, Austria, and the different German states. Some had been uprooted by the wars of Louis XIV, whose national aims were mixed with the cause of Catholicism against Protestantism. Others were put in motion simply by the attractions of the New World, often compounded by persecution at home Pietists, Palatines, Mennonites, Mystics, Moravians, Salzburgers, and others came to the English colonies in such numbers that by the Revolution, it has been esti-

mated, there were some quarter of a million inhabitants of German blood in the colonies.[101]

The first settlement of German Protestants, in this case the people then called Pietists, was made under the auspices of William Penn at Germantown in Pennsylvania in 1683. Winemaking was part of the original intention of the settlers; Francis Pastorius, the leader of the colony, brought vines with him, but they were accidentally spoiled by sea water after they had already arrived in Delaware Bay.[102] No doubt some experiments were made; as late as 1700 Pastorius wrote that the people of Germantown were "especially anxious to advance the cultivation of the vine."[103] But the promise of the town seal, showing a grapevine, a flax blossom, and a weaver's shuttle, was not fully realized: Germantown's weaving prospered, but its wine industry did not.

A second German community was established in 1709 by Protestant refugees from the Rhenish Palatinate (the Rheinpfalz as it is now called), devastated by the War of the Spanish Succession. Thousands of these Germans, from one of the most famous viticultural regions of Europe, had made their way to England, where the English were sympathetic but sorely perplexed to know what to do with them. One answer was to export them to the colonies, usually with the thought of putting to work their talents as winegrowers: had they not come from the very heart of the German wine country? So it was with the group sent over in 1709 under Pastor Joshua von Kocherthal. The gentlemen of the Board of Trade and Plantations proposed that the Palatines, as they were called, should be sent to Virginia or other regions of the continent (they were evidently not very particular) "where the air is clear and healthful" in order to make wine.[104] Kocherthal reported to the board from America that the country was certainly fit for winemaking and that the long history of failure was owing only to "inexperience and want of skill." He mentions Beverley's work in Virginia, which was attracting much notice, and he adds the interesting detail that the Pennsylvania Germans had devised methods for grape growing better suited to American conditions than those of the French.[105] The first contingent of Palatines—more than 2,000 of them—was, however, settled on the Hudson River at Newburgh rather than in Virginia or Pennsylvania. They had a hard struggle to get established, and the official instructions were for them to produce supplies for the English navy rather than wine. Under the circumstances viticulture does not seem to have been seriously tried, though the region is one that must have reminded many of the Palatines of their native Rhineland.[106]

A second contingent of Palatines was sent to the North Carolina coast in company with a number of Swiss emigrants under the charge of Baron Christopher de Graffenried of Bern and of the Swiss traveller Louis Michel: the interests of both men seem to have been largely speculative.[107] The possibility of growing wine was one of the inducements held out to the members of this group, who founded the settlement of New Bern in 1710. Probably some experiments were made, without enough promise to encourage sustained work. New Bern thus provides the model for two later German-speaking colonies in the South already noticed, that of the

Swiss and French at Purrysburgh in South Carolina in 1732 and that of the Salzburgers just across the Savannah River from Purrysburgh, at Ebenezer in Georgia. In both places the manufacture of silk and the production of wine had been part of the original intention, but in both winegrowing was quickly dropped.

One might conclude from this summary account of French and German contributions to early colonial winegrowing that they failed quite as emphatically as the English. Practically speaking, no doubt they did. No continuing, substantial production of wine developed out of any of the trials made by French, German, or Swiss—not to mention those of the Italian Mazzei or the Portuguese Jew De Lyon. But their participation in the early efforts to grow wine in this country helps to make it clear that the consistent failure was not owing to ignorance of established methods. The English may not have known what they were about, but the others brought with them a long tradition. Another, more positive point, is that despite the uniform failure of all who tried winegrowing in the American colonies, it was especially the continental immigrants rather than the English who kept on trying. Their matter-of-course relation to wine as a daily necessity of diet was of incalculable importance in finally establishing an industry. The best-known names in the winegrowing trade that did eventually develop in this country are the names of non-English families, who fulfilled a promise that their ancestors could not, but whose ancestors gave the example. The Germans seem to predominate—Kohler, Frohling, Muench, Husmann, Krug, Gundlach, and Dreyfus come to mind at once. But then, in this country, the Germans always outnumbered the French, who were never enthusiastic about emigration without the stimulus of religious persecution. However, the French are part of it too: Pellier, Lefranc, Vignes, and Champlin are only a few of the French names on the list of successful pioneers. The Italians now seem to be almost synonymous with winemaking in America, especially in California, but theirs is really a later story. Enough to say now that without the diffusive influence of Germans and French, the idea of winegrowing in America would not have persisted as it did, nor would the actual achievement have taken the form that it has now.