Domestic Winemaking in Virginia

In Virginia, after an even longer history of settlement, and a greater effort to encourage winegrowing, things were pretty much as they had been. The story there continues to be mostly one of failure, yet down to the Revolution public interest in winegrowing in Virginia not merely persisted but steadily gained in strength. There were even some moments of encouraging achievement, and one has the feeling that had it not been for the Revolution, the Virginians whose names now figure on the roll of Fathers of Their Country might have managed to be Fathers of Native American Wine as well.

In no colony in the years before the Revolution did the actual enterprise of systematically growing and harvesting grapes, and then of crushing them for wine, extend to more than a very few individuals, despite subsidies, premiums, special prerogatives, exhortations, legislation, and penalties. Doubtless thousands of small farmers and town-dwellers ventured to try how a few gallons of native grape juice might turn out after fermenting; of these, in the nature of things, no record exists. But it is possible to identify a considerable number of proprietors who grew grapes and made wine, with varied success, either on their own initiative, or with public encouragement, or both. Hardly anyone in those days undertook the experiment without a surge of patriotic enthusiasm and a hope that the glory of bringing sound, cheap, American wine to his countrymen might be his.

The Virginians are much the most prominent in the account of purely domestic

16

The engraved title of Robert Beverley's History and Present State of Virginia

(London, 1705). Beverley not only provided an account of the grapes of Virginia

and of hopes for winemaking but went on to make wine successfully at his estate,

Beverley Park. (Huntington Library)

winemaking, and most prominent among them in the early eighteenth century was Robert Beverley (c. 1673-1722), author, in 1705, of the first comprehensive history of Virginia, and a planter at his estate of Beverley Park. This lay in King and Queen County, at the headwaters of the Mattapony, about thirty miles north of modern Richmond, in what was then the wilderness of the Middle Neck. Beverley was an enthusiastic champion of Virginia and its resources. As one of the largest of Virginia landowners, he was interested in promoting settlement, especially Huguenot settlement, on his property, and he was therefore liable to exaggerate the winegrowing potential of his country. But even after allowing for the excesses of mingled commercial and patriotic interest, we find in Beverley's History what, in the authoritative opinion of U. P. Healrick, is the "best account of the grapes of Virginia . . . in the later colonial times."[23] There are six native sorts, Beverley writes: red and white sand grapes; a "Fox-grape," so called for its smell "resembling the smell of a fox"; an early-ripe black or blue grape; a late-ripe black or blue grape; and a grape growing on small vines along the headwaters of streams—"far more palatable than the rest."[24] Compare this list with that of Robert Lawson, written about the same time not very many miles farther to the south, and one sees why it is that such early accounts are the despair of later classifiers.

Beverley thought that good wine could be made from these natives, believing that earlier failures were all caused by the malignant influences of the pine lands and salt water that affected all the early, lowland vineyard sites. The grape, he correctly thought, wanted well-drained hillside slopes. Beverley complained that so long as the Virginians made no serious effort to domesticate their wild grapes, they could hardly attempt making wine and brandy; but he also seems to have thought that the European vine would flourish in Virginia—if suitably removed from the malignant influences already named.[25]

Within a few years of publishing his History , Beverley put his own recommendations into practice, planting a vineyard of native vines upon the side of a hill and producing from it a wine of more than local celebrity. News of it travelled even to London, where the Council of Trade and Plantations was informed in December 1709 that Beverley's vineyards and wines were the talk of all Virginia.[26] A visit to Beverley at Beverley Park in November 1715 is reported in some detail in the journal of John Fontaine, an Irish-born Huguenot then travelling in Virginia. Fontaine, who had been in Spain and had some knowledge of Spanish winemaking practice, observed that Beverley neither managed his vineyard nor made his wine correctly according to Spanish methods, though he does not explain what he means, or why he thought that Beverley should have known how to follow the Spanish way. Beverley could hardly be expected to duplicate, in his pioneering situation, the procedures of an ancient winemaking tradition. For the rest, Fontaine was pleased by Beverley's arrangements on the frontiers of settlement: he had three acres of vines, he had built caves for storage, and had installed a press; by these means he had produced 400 gallons in the year of Fontaine's visit (if all three of Beverley's acres were producing, that figure implies that his vines were yielding about one ton an

acre, an extremely low, but not surprising, yield considering that he was growing the unimproved natives). The origin of the vineyard, so Beverley told Fontaine, was in a bet that he made with his skeptical neighbors, who wagered ten to one that Beverley could not, within seven years, produce at one vintage seven hundred gallons of wine: "Mr. Beverley gave a hundred guineas upon the above mentioned terms and I do not in the least doubt but the next year he will make the seven hundred gallons and win the thousand guineas. We were very merry with the wine of his own making and drunk prosperity to his vineyard."[27] Fontaine seems to say that Beverley actually began his vineyard for a wager, but that cannot be so. As we have seen already, his experiment was the talk of all Virginia as early as 1709, six years before Fontaine's visit. And, as another witness reports, it was Beverley's constant bragging about the prospects of the small vineyard he had already planted that provoked his neighbors to make the bet.[28]

Fontaine, incidentally, has left us another reference to Virginian wine in the next year, in a well-known passage describing the luxurious style kept by the gentlemen of Governor Alexander Spotswood's expedition of exploration to the Shenandoah Valley. On 6 September 1716 the company celebrated its crossing of the Blue Ridge thus:

We had a good dinner. After dinner we got the men all together and loaded all their arms and we drunk the King's health in Champagne, and fired a volley; the Prince's health in Burgundy, and fired a volley; and all the rest of the Royal Family in Claret, and a volley. We drunk the Governor's health and fired another volley. We had several sorts of liquors, namely Virginia Red Wine and White Wine, Irish Usquebaugh, Brandy, Shrub, two sorts of Rum, Champagne, Canary, Cherry punch, Cider, Water etc.[29]

What can the "etc." after "water" possibly stand for? Fontaine does not describe the Virginia red and white wines, but it is highly interesting to know that Robert Beverley was one of this merry party; he might well have been the source of the wine. But so, too, could the expedition's leader, Governor Spotswood, for in 1714 he had sponsored a settlement of Germans at a place called Germanna. We know that this group was making wine a few years later, and it is possible that they had experimented with wild grapes before 1716.[30] If both Spotswood and Beverley had provided samples of their wine, the gentlemen of the expedition may have carried out what would have been a very early comparative tasting of native wines. One doubts that they were in a condition to make very discriminating judgments on the day Fontaine describes.

Beverley won his bet. In the second edition of his History (1722), he wrote that since the book had first appeared "some vineyards have been attempted, and one"—evidently his own—"is brought to perfection, of seven hundred and fifty gallons a year."[31] Such was the flow of wine at Beverley Park, so the Reverend Hugh Jones stated, that Beverley's "whole family, even his negroes drank scarce any thing but the small wines." As for Beverley's "strong wines," which Jones says he often drank, they were of good body and flavor, the red reminding him of the

17

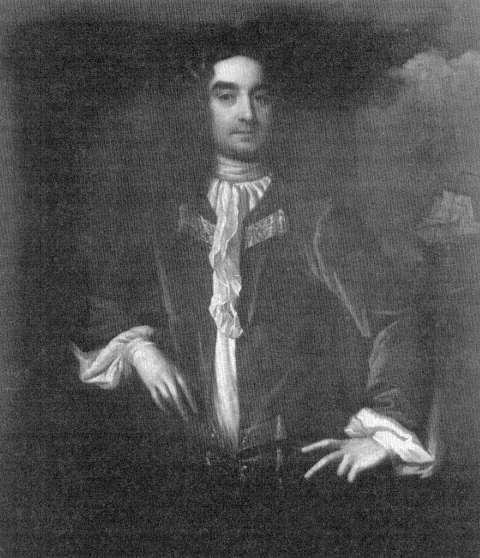

An eager promoter of his Virginia lands, William Byrd (1674—1744) planted many different sorts of

vines at Westover and hoped that Swiss immigrants would turn his "Land of Eden" property near

Roanoke into a country of vines and wines. (Portrait by Sir Godfrey Kneller; Virginia Historical Society)

taste of claret and the strength of port. As the allusion to port suggests' "strong wine" must have meant wine fortified with brandy or other spirit. Jones adds that European grapes were flourishing in Beverley's vineyard, though we cannot know what the truth of this assertion was.[32]

As did almost every eighteenth-century gentleman who experimented with winemaking, Beverley took it as his patriotic duty to sponsor the development of a national viticultural industry. Though I have found no other record of the fact, according to the statement of a later Virginia winegrower, Beverley unsuccessfully urged the Virginia Assembly to pass an act "for the Education of certain Viners and Oil Pressers."[33] Beverley is also said to have put the thousand guineas that he had won on his wager over his vineyard into "planting more and greater vineyards, from which he made good quantities of wine, and would have brought it to very high perfection, had he lived some years longer."[34] But he was dead by 1722, and though his only son, William, survived him and prospered greatly, building a notable mansion called Blandfield, we do not hear that he carried on his father's work as a viticulturist.

Beverley's example probably inspired his brother-in-law, William Byrd of Westover, the best known today of early eighteenth-century Virginians, to experiment with vine growing on his Tidewater estate. Some time in the late 1720s, Byrd collected all the kinds of grape vines he could get and planted a vineyard of more than twenty European varieties "to show my indolent country folks that we may employ our industry upon other things besides tobacco."[35] Byrd also proposed to graft European scions on native roots, a prophetic idea. He corresponded with the London merchant and horticulturist Peter Collinson, who advised him on viticulture and encouraged the trial of native grapes. Among Byrd's manuscripts is a treatise on "The 'Method of Planting Vineyards and Making Wine" from some unidentified source, perhaps compiled for Byrd at his request.[36]

By 1736 his example had had some effect, for his neighbor Colonel Henry Armistead had determined to try his hand. Both the colonel and his son, Byrd wrote, were "very sanguine, and I hope their faith, which brings mighty things to pass, will crown their generous endeavors."[37] But Byrd's hopes were chilled when spring frosts destroyed his crop that year, and a year later he wrote to his correspondent Sir Hans Sloane, president of the Royal Society, that "our seasons are so uncertain, and our insects so numerous,that it will be difficult to succeed." Perhaps, he added, the Swiss whom he hoped to settle in the mountains around Roanoke—Byrd's "Land of Eden"—would succeed better; but that dream never materialized.[38] But if Byrd himself did not succeed, he never doubted that others would in time. He wrote to the English naturalist Mark Catesby in 1737:

I cannot be of your opinion, that wine may not be made in this country. All the parts of the earth of our latitude produce good wine—and tho' it may be more difficult in one place than another, yet those difficulties may be overcome by good management, as they were at the Cape of Good Hope, where many years pass'd before they could bring it to bear.[39]

18

The London merchant Peter Collinson, a distinguished amateur naturalist,

corresponded at length with William Byrd on the subject of grapes; the

drawing shown is from a letter of instruction from Collinson to Byrd about

1730. Collinson had the interesting idea that native grapes might be the right

choice for Virginia: "Being natives perhaps they may be better adapted to your

seasons, than foreigners." (Virginia Historical Society)