4—

Exposition Fever Carried East

As is customary in these expositions, one goal is to promote architecture, which in our country has come to need promotion. . . For the exposition hall, one's heart desires the application of Ottoman architectural science, or the "Arabic" and the "Moorish," or the Indian, Arab, African, and Andalusian architectural science—in short, an Islamic architectural science.

"On the General Exposition," Basbakanlik Arsivi, Yildiz, Kisim 31, Evrak 1933, Zarf 45, Kutu 82; 19 Sefer 1311 (August 1893)

Exposition fever in the mid-nineteenth century extended to the Ottoman Empire and Egypt, where events similar to those in the West were organized. The Ottoman government planned two exhibitions in Istanbul, one in 1863, the other in 1894. The first was a successful venture, but the second did not materialize because of a major earthquake in 1894 that caused great damage to the capital and required huge expenditures of the government's already limited funds. In the Egypt of Isma'il Pasha, the spectacular opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 replicated elements of the international fairs—among them an ephemeral architecture and many festivities.[1] Perhaps more important, however, as at the European and American fairs, the host country became the spectacle's central feature. For both the Ottoman Empire and Egypt this visibility was crucial, since their restructuring efforts in the nineteenth century were intended to make them part of modern civilization, and hence the Western world.

The Ottoman General Exposition, 1863

The date of this first exposition is significant because it precedes that of most of the larger exhibitions in Europe and America. Before 1863, only four major international exhibitions had taken place: in 1851 and 1862 in London, in 1853 in New York, and in 1855 in Paris. The Ottoman Empire had participated in all but the one in New York, where transportation costs had prevented its attendance. The 1863 exposition indicated the willingness of the Ottoman Empire to become part of modern civilization. It took place in the third year of Sultan Abdülaziz's reign, which proved to be one of the most intense periods of Westernizing reforms as well as a time of much city-building activity. As noted in chapter 2, Abdülaziz himself later visited the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition, demonstrating his personal interest in these events.

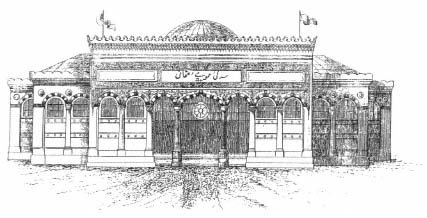

Figure 92.

Front facade of the main hall, Ottoman General Exposition, Istanbul, 1863

(Mirat, no. 3, Zilkade 1279/April 1862).

The 1863 Sergi-i Umumi-i Osmani (Ottoman General Exposition) borrowed its format from the Western exhibitions, but its scope was smaller and its goals more directly linked to the promotion of national industry—a larger program that had been hard hit in the nineteenth century by competition from European products as well as the special rights and privileges given by the Ottoman government to Western entrepreneurs and industrialists from the 1830s on. The exposition was to help in pinpointing the problems of Ottoman industry and in seeking solutions. Initially it was conceived of as a national display, but eventually European industries, assumed to have the most advanced machines and tools, were encouraged to participate.[2]

The Hippodrome—a large open space, centrally located and historically important—was chosen as the exhibition site. The government wanted an exhibition building in the "new manner" (tarz-i cedid ).[3] The commission was given to two French architects already working in the empire on imperial commissions: Marie-Augustin-Antoine Bourgeois, who had designed the Ministry of Defense headquarters in Beyazit, and Léon Parvillée, then working on the documentation and restoration of Ottoman monuments in Bursa. Bourgeois was to design the overall architecture, Parvillée the interior.[4]

The building was a large rectangle that occupied approximately 3,500 square meters (Figs. 92–93).[5] A projecting section, higher than the rest of the building, defined the main facade. Here was the arched entry porch, marked by a

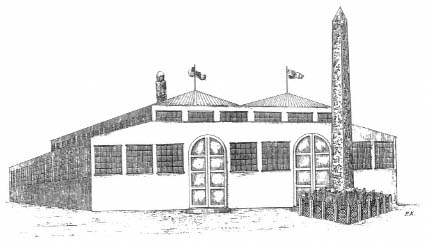

Figure 93.

Back facade of the main hall, Ottoman General Exposition, Istanbul, 1863

(Mirat, no. 3, ZilKade 1279/April 1862).

crenellated roofline. An inscription above the three central arches read "Ottoman General Exhibition." The precedent for the design—a large hall, which could be partitioned—came from previous exhibitions. Nevertheless, the facades expressed local color through an Islamic architectural vocabulary: arches of alternating red and white stones, Ottoman columns and capitals, elaborated rooflines. Not all of these forms were Ottoman (the crenellation, for example, was Cairene), but the "envelope" of the otherwise "new manner" structure was broadly neo-Islamic in style.

The interior was divided into thirteen sections for displaying such items as agricultural products, handicrafts, textiles, industrial products, mining products, leather goods, furniture, carpets, and musical instruments. In one section architectural models and drawings were displayed together with photographs, charcoal drawings, paintings, maps, prints, and books.[6] But agricultural goods occupied the largest space. For example, 212 kinds of wheat from different regions of the empire were shown,[7] emphasizing agriculture as the leading force in the Ottoman economy.

Machines sent from abroad were exhibited in an annex south of the main hall that was reserved for national displays. A simple structure with none of the embellishment of the main building, it extended from the obelisk to the south end of the Hippodrome, enclosing the Serpent Column within its boundaries.[8]

The Istanbul Exhibition became a popular event. Men could visit it five days

a week, women only on Wednesdays and Saturdays. Public transportation fares from neighboring suburbs and towns were reduced to encourage attendance, and, as in the Western world, recreation and entertainment facilities were provided on the fairgrounds. For example, on Fridays and Saturdays the army band (Asakir-i Nizamiyye-i Sahane Muzikasi) gave free concerts. The exposition generated a great deal of commercial and tourist activity, and many foreigners, among them journalists, entrepreneurs, and industrialists, came to Istanbul specifically to visit it.[9] The building was torn down in 1865.[10]

The Istanbul Agricultural and Industrial Exposition, 1894

A second exposition in Istanbul was conceived in 1893 under Abdülhamid II, with the goal of "promoting the development of the wealth and well-being of the country."[11] A 142,000-square-meter site on the northern side of the Golden Horn, near Sisli, was selected for the Istanbul Agricultural and Industrial Exposition (Dersaadet Ziraat ve Sanayi Sergi-i Umumisi).[12] Unlike the 1863 exposition, this one would be permanent but would close for four months each winter. Although the major exhibits would consist largely of agricultural, industrial, and artistic products of the empire, foreign goods would also be displayed, and some foreigners would sit as regular members on the committee formed to organize the exhibition.[13] Therefore, while bringing "under the eye of agricultural and industrial Europe a complete collection of products of the soil and toil of the Empire," the exhibition would simultaneously "show to the native industrialists and agriculturists such foreign methods, models, and types of production as might enlarge their ideas of their own work and enable them to improve it as to render Turkey in an economic sense less and less tributary to foreign countries."[14] The exhibition would double as a marketplace; the products would be offered for sale, and purchasers as well as visitors would be admitted.[15]

As in the West the promoters of this exposition emphasized its educational, social, and recreational benefits. An editorial in The Levant Herald and Eastern Express argued that although the capital had open spaces with pleasant views and fresh air, none of them were "interesting, nor did any of them offer any intellectual attraction whatsoever nor quicken healthy curiosity." If managed properly, the planned exhibition could do all these things. The site was well chosen, because Sisli was a healthful spot. With its physical and intellectual

appeal, the exhibition had the potential to bring together "all classes of the population."[16]

The organizing committee decided that because the exhibition was to be permanent, the pavilions should be built of long-lasting materials—stone, brick, and iron.[17] Visitors arriving at the site from Pera would see two facades of the main building. Inside, to the left of the entrance, would be an area for foreign machines and instruments and for hothouses. A large hall (under a glass roof), intended for the inaugural ceremony, would occupy the center. To the right of the entrance an area was reserved for displaying livestock and dairy farming. A field for agricultural experiments and a hippodrome were planned for the northeast section. The buildings, including an imperial pavilion, would cover 44,000 square meters. A rail transportation system would facilitate communication on the site.[18]

The architectural style of the pavilions was a major concern. A government document argued for the serious consideration of the issue because the goal of exhibitions was promotion, including promotion of architecture, and in the Ottoman Empire the "science of architecture" (fenn-i mimari ) had been forgotten. Even the design of buildings, on which great sums had been spent, did not follow "architectural rules" (kaide-i mimari ). To develop such rules required the study of "Ottoman architectural science" (fenn-i mimari-i Osmani ) or of Arabic, Moorish, Indian, African, and Andalusian "architectural styles"—in short, an "Islamic architectural science" (fenn-i mimari-i Islami ). Nevertheless, some buildings would be designed in the "new manner." This was the "Renaissance" style, based on the "Roman," "Greek," and "Gothic" architectural rules and observed in many architectural drawings received from Europe. The logic for selection among the Western styles was simple: "Whatever is considered prestigious in Europe will be used in the architecture of the exhibition."[19] Despite its great confusion, this argument reflects the basic dilemma Ottomans encountered in choosing an appropriate style—reduced to the juxtaposition of Islamic versus European.

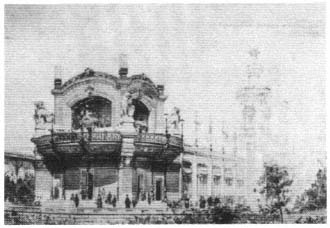

Raimondo D'Aronco, well known as a practitioner of the Italian branch of art nouveau, the stile floreale, was chosen as the architect of the exhibition. Only two of his numerous drawings have surfaced in the archives of the Dolmabahçe Palace: one depicts a setting for ceremonies (possibly the imperial pavilion) and the other the British pavilion (Figs. 94–95).[20] The first is an interpretation of Islamic forms in new materials (i.e. the iron-ribbed dome and the

Figure 94.

D'Aronco, pavilion for the Istanbul Agricultural and Industrial

Exposition, Istanbul, 1894 (D'Aronco architetto ).

arcades); the second is a typical stile floreale structure, with oversized sculptures applied to the facades, the decorative use of metalwork, large windows, and curving lines. These two drawings represent the two architectural styles, neo-Islamic and modern European, written into the program by the organizing committee.

D'Aronco's scheme for the exhibition grounds included landscaping. At the center of the site would be the People's Palace, surrounded by "all the features of (landscape) gardens—shrubberies, avenues, fountains, etc."[21] When D'Aronco presented the drawings, the sultan expressed his satisfaction by conferring a decoration on him and agreed to hire Italian master builders for the construction work.[22] A few months later a huge model of the exhibition grounds was brought before the sultan; measuring 3.0 by 2.5 meters, it was seen as "a masterpiece, perfect in every detail, . . . a work of rare beauty and finish, a work of art."[23]

The plan for the 1894 Istanbul Agricultural and Industrial Exposition was ambitious in its social aims, its hopes for economic benefits, and the grandeur of its architecture. Like exhibitions in Western cities, it was seen as an arena of architectural experimentation. Although the pavilions were never built and most of the drawings and the model have been lost, the discussion of architectural styles sheds light on the Ottoman Empire's search for an architectural philosophy.

Figure 95.

D'Aronco British pavilion, Istanbul, 1894 ( D' Aronco architetto ).

The Opening of the Suez Canal, 1869

Among the grandiose schemes undertaken by Isma'il Pasha, the opening of the Suez Canal, which joined, in the words of Théophile Gautier, the "Mer de Perle" to the "Mer de Corail,"[24] highlighted Egypt's importance to European trade. The canal, by providing much easier access between England and India, ultimately led to the British occupation of Egypt; but the original impetus for the project had been "global." In the 1830s the Saint-Simonians promoted the idea so that goods could circulate freely throughout the world and encourage worldwide industrialization.[25] Three decades later, Isma'il Pasha brought in a Saint-Simonian, Ferdinand de Lesseps, to lead the project. Most likely, however, Lesseps was commissioned not because of his ties to utopian socialism but because of his credentials as an engineer.

For the inaugural ceremonies only a few permanent buildings were built in Ismailiyya, the new town that owed its existence to the canal, but temporary structures were erected, many of them inspired by the architecture of the universal expositions. As at the expositions, the number of visitors (both local and foreign) was overwhelming, but in this case their expenses were paid by the Egyptian khedive. The ceremonies, feasts, and entertainment further recalled the European fairs.

The magnificence of the three-week-long inaugural ceremonies reminded some observers of The Thousand and One Nights . Many notable political and

literary figures attended the celebration, among them the Austrian emperor Franz Joseph, the king of Hungary, the prince of Prussia, and the prince and princess of Holland. Undoubtedly the most valued guest, however, was the French empress Eugénie, for whom the khedive built a palace on the Nile, a replica of her private apartments in the Tuileries.[26] Eugénie, on the day she arrived in Port Said, sent a telegram to Emperor Napoleon III: "I arrived at Port Said in good health. Magnificent reception. I haven't seen anything like it in my lifetime."[27]

The khedive did not include Muslim sovereigns among his guests. He apologized by admitting that he would have invited, among others, the sultan of Morocco, the shah of Persia, and the bey of Tunis, but he had to limit invitations because accommodations were unavailable. He wrote to Nubar Pasha: "With the best intentions on earth, and opening all my residences, I could not have more than eighty palaces ready for the sovereigns and princes who would like to honor me with their presence."[28] As rapprochement with the West was his goal, European leaders were naturally given preference over Muslim leaders.[29]

Among the scholars and writers attending were the famous German Egyptologist Richard Lepsius, the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, the French painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, and the French writer Théophile Gautier. A large contingent of journalists was also present.[30] These guests were distributed among the main hotels of Cairo, and a large group was housed in the renowned Hotel Shepheard. Gautier wrote that

the guests would group at tables according to their affiliations or professions; there was the corner of painters, the corner of scholars, the corner of literary people and reporters, the corner of worldly people and amateurs. . . . They visited one another. . . . The conversation and the cigar blended all the ranks and all the nations; one saw German doctors talking about aesthetics to French artists and serious mathematicians listening to the tales of the journalists with smiles.[31]

At least according to Gautier, the atmosphere of friendly communication transcended national barriers—one of the stated goals of international exhibitions.

Isma'il Pasha entertained his foreign guests lavishly in Cairo, on the boat trip down the Nile to Ismailiyya and in Ismailiyya. The boat trip was splendid,

with stops at ancient sites like the Temples of Luxor and Saqqara. Sometimes meals were served in ancient temples, but more often tents were erected—in the middle of the desert in Saqqara, for example, in honor of Empress Eugénie. They were silk ecru on the outside, and some were covered with yellow satin, others with red satin, on the inside; the color of the furniture in each tent matched that of the interior.[32] In the tents in Ismailiyya seven to eight thousand guests dined in "unheard-of luxury."[33]

The crowds included Egyptians as well as foreigners. Isma'il Pasha declared:

The inhabitants of all the regions of Egypt, including the tribes of Sudan, will unite in Ismailiyya; there will be national games and entertainments. . . . [This is planned] out of respect for both the religious sentiments of the large majority of the country's population and the national customs and historical traditions of modern Egypt.[34]

The governor also saw touristic value in these indigenous ceremonies. He urged foreign guests to visit Arab feasts,[35] where the entertainment included bands, chanting, folkloric dances, performing dervishes, fire-eaters, and karagöz, the shadow theater. Empress Eugénie was especially amused by the performances of bedouin horsemen "galloping to and fro, shouting, and firing off their meskets ."[36] Tents were erected for the chiefs of local tribes, decorated with colorful carpets and "all the splendors of . . . the Orient" (Fig. 96). The chiefs in white robes, surrounded by their servants, either stretched on divans or stood in front of their tents and invited passersby in for coffee, chibouk, and sherbets.[37] The noises made by the many horses and donkeys mingled with the "rowdy music of the desert orchestras." Dervishes howled and whirled, and singers from Upper Egypt sang in high-pitched voices.[38] This was a tableau vivant, an ethnographic display of the indigenous—learned from the international exhibitions. Indeed, the accounts of the European observers recalled the descriptions of world's fairs with their emphasis on race:

All the examples of Semitic races are here; all the people subject to Islam have sent their representatives: the Persian brushes past the man of Morocco and the man of Zanzibar; the inhabitant of Arabia has put up his multicolored tent next to the striped cone of the Indian.[39]

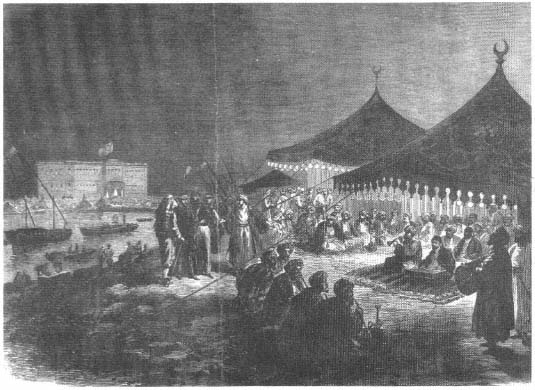

Figure 96.

Tents of local people, Ismailiyya, 1869 ( The Illustrated London News, 18 December 1869).

This was a "most varied and bizarre spectacle,"[40] which created a "marvelous effect." Here, as in the Islamic quarters of the 1867 Universal Exposition in Paris, there was a "brilliantly organized disorder."[41]

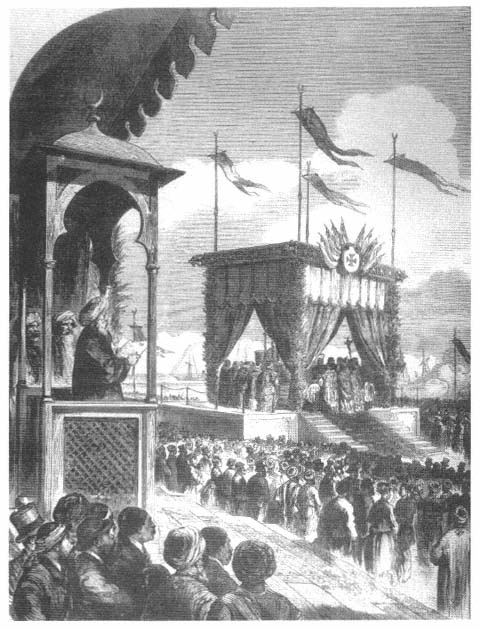

In Ismailiyya, three elevated pavilions with broad stairways were set up for the opening ceremony (Figs. 97–98). The first contained seats for the khedive, his imperial and royal guests, and their attendants; the second was for the Catholic church; and the third for the Muslim ulama. All were built of wood and adorned with flowers and the flags of guest nations. Golden crescents rose from the corners of each pavilion. On the Christian sanctuary there was a cross of Jerusalem, and on the Muslim pulpit an inscription from the Qur'an. The ceremonies began with a Muslim prayer, followed by a Catholic mass conducted by the archbishop of Jerusalem, and a speech by Monsignor Bauer

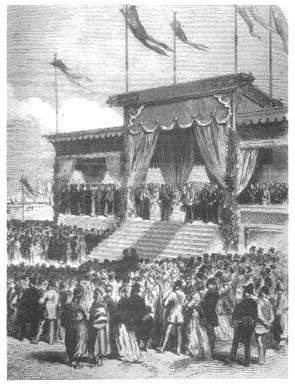

Figure 97.

Pavilion for the khedive and his guests, Ismailiyya,

1869 (The Illustrated London News, 11 December 1869).

(Empress Eugénie's confessor), who compared Ferdinand de Lesseps to Christopher Columbus.[42]

The town of Ismailiyya was "dressed up" for the occasion. The tents of the Arab chiefs, multicolored and bedecked with banners, were placed between Lake Timsah and the canal. The long line of tents for the khedive's guests stood across from Lesseps's house, on the Avenue of Victoria; there were more than twelve hundred, each one providing shelter for three people. Thus a temporary settlement was built next to the permanent town. In the words of one French guest, the walls of this city were made of "the most beautiful carpets in the world and white linens, all suffused with sunlight."[43]

At one end of the embankment stood the khedive's palace, 72 by 25 meters, built in only six months. The long facade of the two-story structure faced Lake

Figure 98.

Pavilion for the Muslim ulama (left) and pavilion for the representatives of the

Catholic church (right), Ismailiyya, 1869 ( The Illustrated London News, 11 December 1869).

Timsah. A round veranda, furnished with sofas, led to the main staircase in the grand vestibule, decorated in "Moorish" style. On either side of the vestibule were reception rooms in "Arab style" with polychrome stained-glass windows and intricate woodwork. The second story of the palace had not been completed by the time of the inauguration ceremonies. For the main reception, a special hall large enough to accommodate a thousand tables was built on the dunes facing the palace. The dining room for the visiting sovereigns abutted this hall; it was transformed into a tropical garden with plants brought from the greenhouses and gardens of the Gazira Palace. The chandeliers, the furniture, the paintings, the fountains, and the mirrors were in the "latest Parisian taste."[44]

Ismailiyya was further decorated by Venetian masts with glittering streamers, flags in lively colors, garlands, arches of triumph, and inscriptions in honor of Isma'il Pasha and the guest sovereigns. Here a new city was to be built; its layout was marked on the ground and the names of the future arteries were indicated on large bands of cloth: Avenue of Empress Eugénie, Avenue of the Prince of Prussia, Avenue of Franz-Joseph—to honor Egypt's royal guests. At night, fireworks transformed the streets of Ismailiyya into "rivers of fire."[45]

The inauguration of the canal marked a new era for Isma'il Pasha's Egypt, one that saw Cairo's old fabric regularized and new quarters built in the Haussmannian manner. New social and cultural customs, moreover, were imported into Egypt from Europe, all of them rehearsed at the inaugural ceremonies for the Suez Canal. According to a French guest: "at night, the salons of Cairo and the theaters welcome the guests. White tie is worn, and the evening begins at the house of a pasha or a bey; [it] ends at the Italian opera or the French theater or even the circus."[46]

The newspaper Nil projected the changes to come, beginning in the winter season following the Suez Canal festivities:

This season will show the old city of the caliphs to foreigners under a new light. Balls, concerts, vaudevilles, circuses, ballets, all kinds of performances, first-class hotels luxuriously furnished, entertainments and feasts of all kinds. . . . Nothing will be lacking this winter in the Paris of the Orient.[47]