Universal Exposition of 1867, Paris

As representatives of Islamic urban settings, Ottoman and Egyptian quarters were placed adjacent to each other in 1867 in Paris, and, despite their independent designs, they formed an ensemble: visitors could meander through the Egyptian street into the Turkish square. Both quarters were deliberately made irregular to reflect the tortuous streets with many dead ends of Islamic cities. The choice of an irregular urban fabric to represent Istanbul and Cairo at the fairs reflects one of the dilemmas of Ottoman and Egyptian officials and their European advisors. Even though in both Istanbul and Cairo the 1860s were marked by an intense campaign to regularize the network of streets, to create monumental avenues and vistas, and to establish large urban squares—all lessons learned from Haussmann's rebuilding of Paris—the exposition planners turned to the past, to an image that they considered outdated but that the West associated with Islam.

As I mentioned in the introduction, the definition of cultural identity was much debated among the Westernizing Turks and Egyptians during this intense period of sociocultural transformation. Some called for maintaining the old cultural forms while adopting Western technology; others wanted either to incorporate new elements into the local culture, thereby creating a rupture between the old and the new, or to evaluate and redefine their self-identity according to Western views. The architectural representations of Egypt and the Ottoman Empire in Paris in 1867 belong to the latter trend.

The Egyptian quarter at the 1867 fair consisted of three buildings on a street: a temple, a selamlik (a small palace), and an okel (a covered market, or caravansary) (see Figs. 70–75). The temple, a replica of the temple of Philae, was a museum where antiquities were exhibited; an avenue lined with sphinxes led to its entrance. Together, the temple, selamlik, and okel were intended to convey the complete history of Egypt. The temple stood for Egyptian antiquity, the selamlik for the nation's Arab civilization, and the okel for contemporary industrial and commercial life. Between the okel and the temple was a copy of Bartholdi's statue of the famous Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion, who seemed to meditate on a future when "the veil covering forty centuries of history would be torn."[9] A pavilion called the Isthme de Suez displayed docu-

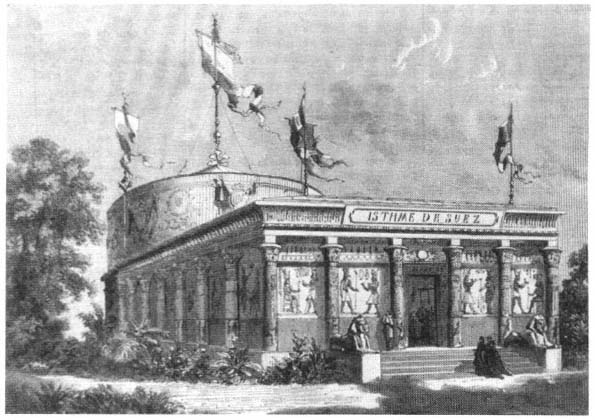

Figure 22.

Suez pavillon, Paris, 1867 (L'Exposition universelle de 1867 illustrée ).

ments and models of Ferdinand de Lesseps's work on the Suez Canal, then under construction, as well as the geography and the natural history of the site (Figs. 22–23).

In 6,000 square meters, a "condensed and miniature Egypt" was presented to the world, a "brilliant, splendid" achievement, in the eyes of the general commissary to the Egyptian exposition, and one that "revealed [Egypt's] past grandeur and its present richness."[10] The effort was applauded by the West. One French journalist, for example, argued that no other country had understood the idea of a universal exhibition as well as Egypt, which displayed its

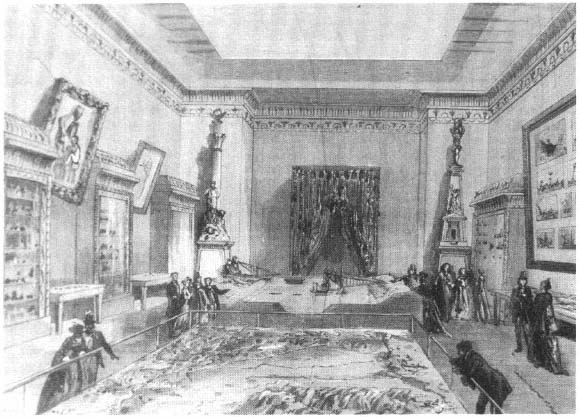

Figure 23.

Interior of the Suez pavillon, showing models of the canal area, Paris, 1867 ( L'Exposition universelle de

1867 illustrée ).

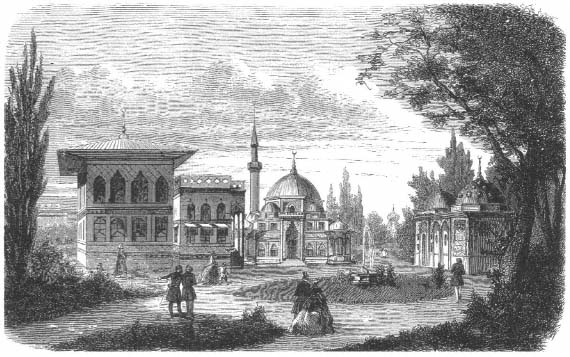

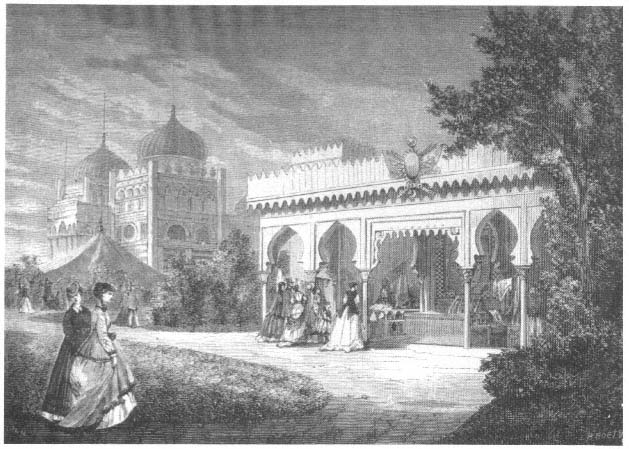

Figure 24.

The Turkish quarter, view (from left to right) of the Pavillon du Bosphore,

the mosque, the fountain, and the bath, Paris, 1867 ( L'Illustration, 2 March 1867).

past and its present.[11] Hippolyte Gautier praised the Egyptian quarter as "not only one of the most sumptuous, but also the most complete and the most instructive."[12]

The Egyptian exhibition had attempted to encapsulate Egypt's history. The Ottoman Empire, in contrast, condensed its cultural and social life in a selection of building types. The Ottoman section, designed by Léon Parvillée, was composed of three buildings—a mosque, a residential structure called the Pavilion du Bosphore, and a bath—around a loosely defined open space. In the center of this space was a fountain (Fig. 24). The mosque represented the religious sphere; the Pavilion du Bosphore, the homefront; the bath, social and cultural ritual; and the fountain, the public sphere. On the occasion of Sultan Abdülaziz's visit, a triumphal gate to the quarter was erected; with its formal

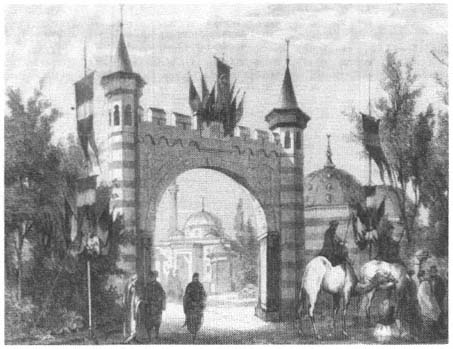

Figure 25.

Gateway to the Turkish quarter, Paris, 1867 ( L'Exposition universelle de 1867 illustrée ).

references to the gates leading to the different courts of the Topkapi Palace and its imperial tugra , "sultan's seal," it symbolized the imperial presence (Fig. 25).

Like that of the Egyptian section, the layout of the Turkish quarter was deliberately irregular, even though the basic premise—a square open space with a fountain in the center, surrounded by buildings with symmetrical facades—did not call for it. This arrangement was derived not from Turkish precedent but from French academicism. The idea was to create by irregularity an "authentic" and "picturesque appearance."[13]

Not far from the Egyptian-Ottoman complex was another Islamic section, composed of the Tunisian and Moroccan exhibitions (Fig. 26). Perhaps because of their associations with bedouin culture, both had tents for the display of products. Tunisia also had a residential structure, called the Palace of the Bey

Figure 26.

Tunisian palace, Moroccan tent, and Moroccan stables, Paris, 1867 ( L'Exposition universelle de 1867 illustrée ).

because the bey of Tunisia had stopped there briefly during his visit to Paris. The two domes of this palace and the tents created an Islamic skyline. Strolling from the Quai d'Orsay toward the main exhibition hall, a visitor would see first these domes and tents and then the domes and minarets of the Egyptian and Ottoman parks. Hippolyte Gautier called the entire section the Quartier Oriental:

The entire Orient is before you; do not look for machines here, or for the practical inventions of the human mind; you are in the domain of contemplative life: the agreeable precedes the utilitarian, and poetry is intricately mixed into the smallest detail of existence.[14]

People dressed in colorful local costumes, Middle Eastern music coming from the pavilions, and the aromas of local cuisines from the cafés gave the quarter the real flavor of the Orient. According to one observer, "the illusion was complete. . . . To see the Orient . . . it is enough to get on the omnibus."[15]