Chapter One

Victors

We begin with the namaskar mantra . This utterance, also known as the mahamantra or the navkar mantra , is Jainism's universal prayer and all-purpose ritual formula. It is hardly possible to exaggerate its importance. It is repeated on most ritual occasions, and many Jains believe it to contain an inherent power which, among other things, can protect the utterer in times of danger. When, in the summer of 1986, I arrived in Ahmedabad to study Jain rituals, a Jain friend who was assisting me in my research insisted that my first order of business should be to commit the namaskar mantra to memory. One of my most pleasant memories of Jaipur is of an elderly friend pointing with pride to his small grandson who, hardly yet able to talk, had memorized the mantra . A somewhat more disquieting memory is of yet another friend who responded to an allusion to my own nonvegetarian background by hastily mumbling the mantra under his breath.

In essence it is a salutation (namaskar ) to entities known as the five paramesthin s, the five supreme deities.[1] These beings are worthy of worship, and it is crucial to note that these are the only entities the tradition deems fully worthy of worship. They are, in order, the arhat s ("worthy ones" who have attained omniscience; the Tirthankars), the siddha s (the liberated), the acarya s (ascetic leaders), the upadhyayas s (ascetic preceptors), and the sadhus (ordinary ascetics). The mantra 's importance to us is that it is a charter for a type of ritual, singling out a certain class of beings as proper objects of worship. These beings, we see,

are all ascetics.[2] This is the fundamental matter: Jains worship ascetics, and this is the most important single fact about Jain ritual culture.

This chapter deals with ascetics as objects of worship among the Jains. Who are they? What qualities single them out from other beings? What makes them worthy of worship? We begin addressing these questions by examining the text of an important ritual. The namaskar mantra lists the arhat s, by which is meant the Tirthankars, as foremost among those who are worthy of worship. The ritual with which this chapter begins is itself an example of Tirthankar-worship. Its text, moreover, tells us something of why the Tirthankar is worthy of worship. After examining this rite, we will consider ideas about the cosmos that inform the rite, and move finally to a discussion of living ascetics as objects of worship.

The Lord's Last Life

Most of my Jain friends and acquaintances in Jaipur were businessmen, many in the gemstone trade. These men were not, by and large, sophisticated about religious matters and did not pretend to be. They were men of business and masters of their craft. They had little time or inclination to worry about or debate the fine points of Jainism.

Nor were they usually very observant beyond a certain minimum. Of course they were all vegetarians. Although I frequently heard the allegation that many men of their sort ate meat on the sly, I saw absolutely no evidence of this. Nonetheless, despite the constant exhortations of ascetics, most did not strictly adhere to such rules as the avoidance of potatoes, and few indeed avoided eating at night. Avoiding vegetables that grow underground (which are believed to be teeming with life-forms) and not eating at night (so as not to harm creatures that might fall into the food) are generally regarded as indices of serious Jain praxis. Most were not daily temple-goers, although I believe most of them knew at least the rudiments of temple procedures. But in spite of a certain amount of behavioral and ritual corner-cutting, by any reasonable standard these men were serious Jains.

One good friend, then a youngish bachelor in whose gem-polishing establishment I spent many an hour, is exemplary of this whole class of men. He knows how to perform the basic Jain rite of worship (the eightfold worship, to be discussed in Chapter Two). He visits a temple about once a week. He usually does so for darsan , for a sacred viewing

of the images, not to perform a full rite of worship. He used to go to an important regional pilgrimage site (at Malpura near Jaipur) every month on full moon days, although this has dropped off because of the pressures of business. He fasts only once a year on the last day of Paryusan, the eight-day period that is the most sacred time of the year for Jains. He performs the expiatory rite of pratikraman on this day also. He certainly does not pretend to live the life of an ideal Jain layman, but he nevertheless identifies strongly with Jainism and holds its values and beliefs in the highest possible esteem.

As do many other men of his general class, condition, and age, he comes from a family in which women are highly observant and usually far more so than the men. His mother performs the forty-eight-minute contemplative exercise called samayik and visits a temple daily. She fasts four times a month, and on fasting days she performs the rite of pratikraman . She has not eaten root vegetables from the time of her birth, and for at least thirty years has not taken food at night. The wife of one of his six brothers follows the same strict pattern as her mother-in-law. His other sisters-in-law visit the temple once or twice a week and fast approximately once a month; they would probably do more, he said, were it not for the responsibility of young children.

And here is the mystery. Even in this rather observant family, my friend told me, the topic of liberation (moks ) from the world's bondage simply never comes up. He added that he does not even remember anyone ever mentioning the word; it just was not part of the family discourse. He himself hardly gives any thought to liberation. Indeed, in response to my queries he ventured the opinion that liberation is really "not possible" at all (meaning, I believe, for people in his own position). In order to attain liberation, he said, you have to renounce the world and devote yourself to spiritual endeavors. "But we," he said, "have our businesses to attend to." He went on to state that most Jains do not actually know what liberation is, and visit temples solely for the purpose of advancing their worldly affairs.

The matter, however, is more complex than my friend's remarks might suggest. Let me say at once that to some degree he was exaggerating, probably for pedagogical effect. For example, the issue of liberation would not normally arise in a family context, but the same individuals might well speak of liberation in more specifically religious contexts. Still, it remains true that the religious lives of most ordinary lay-Jains are not liberation-oriented. Even women's fasting—which is often spectacular and certainly evokes the image of the moks marg (the

path to liberation)—seems often, and perhaps mostly, to be motivated by the desire to protect families, to achieve favorable rebirth, or even to gain social prestige.[3] 1 found a general awareness and understanding of the goal of liberation among Jains with whom I discussed the matter, but liberation tends to be seen as a very remote goal—not for now, not for any time soon.

But at the same time, it is also generally understood that although rituals, fasting, and other such religious activities generate merit (punya ) that will lead to worldly felicity, the goal should be liberation. This is certainly the view promoted by Jain ascetics in their sermons, and it is reasonably well understood by the laity. Many Jains say, as my friend does, that other Jains engage in ritual purely to advance their worldly affairs. But the point, of course, is that one should not be so motivated; one should really be seeking liberation. Given all this, we are presented with a puzzle. Just what is the relationship between liberation and the lives and aspirations of lay Jains?

This puzzle is perhaps nowhere more evident than in the major periodic rites of worship. These rites are, in fact, a vital domain of religious activity for men such as my friend. As Josephine Reynell points out (esp. 1987; see also Laidlaw 1995: Chs. 15-16), there is a basic division of ritual labor among temple-going Svetambar Jains: women fast, while men—too immersed in their affairs to do serious fasting—make religious donations (dana ; in Hindi, dan ). A major field for religious donations is the support of important periodic rites. These are often held in conjunction with calendrical festivals and also on the founding anniversaries of temples. They are frequently occasions for the display of great wealth. Truly startling sums are often paid in the auctions held to determine who will have the honor of supporting particular parts of the ceremony or of assuming specific ceremonial roles. This aspect of sponsorship seems to function as a public validation of who's who in the wealth and power hierarchies of the Jain community. The ceremonies supported by this cascade of wealth are typically sumptuous, lavish occasions—full of color and suggestions of the abundant wealth of the supporters. They seem to have little to do with liberation from the world's bondage.

And yet here is the paradox. If we peel away the opulence and glitter from these occasions we discover that liberation is there, right at their heart. At the center of all the spending, the celebration, the display, the stir, is the figure of the Tirthankar. He[4] represents everything that the celebration is apparently not, for he is, above all else, an ascetic. His

asceticism, moreover, has gained him liberation from the very world of flowing wealth of which the rite seems so much a part. Liberation and the asceticism that leads to liberation are thus finally the central values, despite the context of opulence. Wealth is not worshiped; wealth is used to worship the wealthless.

We now look more closely at an example of such a rite. The example I have chosen is not only a rite of which the Tirthankar is the object; it is also a rite that, in a kind of doubleness of purpose, explains why the Tirthankar is an object of worship.

A Major Rite

The end of the year 1990 was a troubled time in Jaipur. In many north Indian cities the autumn months had been marred by agitations against the national government's decision to implement a far-reaching policy of job reservations for lower castes. In Rajasthan these same months had seen a lengthy and exasperating bus strike. Then, in late October, there were deadly communal clashes between Hindus and Muslims in Jaipur provoked by the efforts of Hindu nationalists to demolish a mosque in Ayodhya, one supposedly built on the site of Lord Rama's [5] birth, and to replace it with a Hindu temple. By December, Jaipur was still a very uneasy city, and for this reason the Jain festival of Paus Dasmi was not celebrated with the usual éclat.

Paus Dasmi is an annual festival celebrated by Svetambar Jains in commemoration of the birth date of Parsvanath. Parsvanath is the twenty-third Tirthankar of our region of the cosmos and era, and is one of the most greatly revered of the Tirthankars. He was born on the tenth day (Dasmi) of the dark fortnight of the lunar month of Paus (December/January), which is why the festival is called Paus Dasmi. In 1990 this day occurred on December 11. In Jaipur this festival is normally the occasion for a major public display of religious symbols. In ordinary years, on the day before Paus Dasmi a portable image of the Tirthankar is taken in public procession from a large temple in Jaipur's walled city to a temple complex at a place called Mohan Bari on Galta Road.[6] There, on the morning of the birthday itself, the image is worshiped, and then on the afternoon of the same day the image is returned to its original temple in another public procession. But in December of 1990 this was not to be. Because of the city's troubles, no permit for the procession could be obtained. Still, at least the basic rite of worship could be performed, and it is this performance that is described in what

follows. It was perhaps fortunate for me that it was celebrated in a relatively small way, for this gave me a chance to observe its performance with special closeness.

The rite is an example of a type of congregational worship commonly known as mahapuja , a "great" or "major" (maha ) "rite of worship" (puja ). Such rites, which come in several varieties, are commonly performed by Svetambar Jains on special occasions in both Ahmedabad and Jaipur. Most of them are directed at the Tirthankars, but I once witnessed a mahapuja for the goddess Padmavati (a guardian deity, not a Tirthankar) in Ahmedabad, and the congregational worship of certain deceased ascetics who are not Tirthankars, figures known as Dadagurus, is central to Svetambar Jainism in Jaipur. The occasions for these rites are quite various. Sometimes, as in the present case, they are performed in conjunction with calendrical festivals. The consecration anniversaries of temples are celebrated by means of these rites, and they are sometimes held to inaugurate new dwellings or businesses. Congregational worship of the Dadagurus is often held in fulfillment of a vow (see Chapter Three). A rite called the antaraynivaranpuja (the puja to "remove obstructive karmas ") is frequently performed on the thirteenth day after a death.

The specific rite to be discussed here belongs to a class of rites known as pañc kalyanakpujas . The expression pañc kalyanak means "five welfare-producing events," and refers to five events that are definitive of the lives of the Tirthankars. Although the Tirthankars have different individual biographies, the truly significant events in the lifetime of each and every Tirthankar are exactly five in number and are always precisely the same.[7] They are: 1) the descent of the Tirthankar-to-be into a human womb (cyavan ),[8] 2) his birth (janam ), 3) his initiation as an ascetic (diksa ), 4) his attainment of omniscience (kevaljnan ), and 5) his final liberation (nirvan ). A pañc kalyanakpuja is a rite of worship celebrating the five welfare-producing events—the five kalyanaks —in the life of a particular Tirthankar.[9] Five-kalyanakpujas are very important as a class of rites, a fact that reflects the importance of the kalyanaks as cosmic events. Five-kalyanakpujas are often performed as part of the ceremony that empowers the images in Jain temples, and this suggests that the Tirthankars' kalyanaks have left a residue of welfare (kalyan ) in the cosmos that can be focused in images and mobilized by rituals in the service of worshipers.

Every major Jain rite of worship is based on a specific text that carries its distinctive story line or rationale. In the case of a pañc kalyanak

puja of the sort to be described here, the story line recounts the five kalyanaks as the key episodes in the biography of a specific Tirthankar. Such texts are always authored by ascetics. The text of the present rite was written by a Khartar Gacch monk named Kavindrasagar (1905-1960) whose chief works include a number of well known pujas . The type of Hindi in which the text is written is easy for participants to understand.

The particular rite performed on Paus Dasmi celebrates the five kalyanaks of Parsvanath. It is, accordingly, called the parsvanathpanc kalyanakpuja , and its story line is an account of the five kalyanaks as they occurred in Parsvanath's own particular career. Participants sing songs from the text that recount and praise each of Parsvanath's five kalyanaks , and at the conclusion of each set of songs certain prescribed ritual acts occur.[10] Sometimes favorite devotional songs not in the text are added. The rite thus consists of five separate groups of ritual acts, each preceded by a group of songs. It should be understood that most participants in such rites are at least minimally conversant with these songs, and some will know some of them or parts of them by heart. The text is as central to the rite as the ritual acts that accompany its singing. The ritual acts (to be described below) are completely standard in the sense that more or less the same ones occur in all rites of this sort. It is the text that embeds the ritual acts in a narrative that differentiates the significance of one type of rite (in this case the parsvanathpañc kalyanakpuja ) from others.

The spirit in which the songs are sung is also very important. The rite is seen as an expression of devotion (bhakti ). For a rite of this sort to be successful, the songs should be sung with gusto and feeling; they should express, that is, the proper spirit (bhav ). Typically, rites of this kind start slowly with a limited number of participants. As time passes, more participants arrive, and at the end—if all is well—the site of the ceremony will be packed with lustily singing devotees. In the case of the particular rite described here, the troubled context kept attendance down, but the singing was spirited.

The ritual acts are the responsibility of a limited number of individuals who are bathed and wearing clothing appropriate for touching sacred images (see Chapter Two). These I call "puja principals." They stand, often in husband-wife pairs, holding a platter containing offerings while the songs appropriate to a given segment of the rite are sung; when the appropriate moment comes they perform the required actions

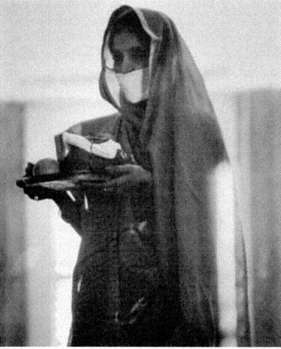

Figure 1.

A puja principal holding offerings in

Jaipur. Note the mouth-cloth designed to prevent im-

purities from being breathed on the image.

(see Figure 1). Because of the troubled atmosphere in the city, in this case the temple's pujari (ritual assistant) was the sole puja principal; normally there would have been several drawn from the city's lay community. The other participants serve as both singers and as a sort of audience (though they are not pure spectators). Remaining seated, they sing the puja's verses and witness the puja principals' acts. In the case in question about a hundred participants of this sort were on the scene by the ceremony's end.

We thus see that the role of worshiper is actually manifested in two ways in rites of this sort. The puja principals are in physical contact with the image; others are at an audience-like distance. In a sense the puja principals "do," while the others felicitate what is "being done." Jains believe that one's approval (anumodan ) of another's good deed is spiritually and karmically beneficial, and the division of ritual labor

seems to capitalize on this concept; by means of vocal participation an indefinite number of individuals can partake of the benefits of the rite.[11] Svetambar Jain ritual culture is of the do-it-yourself sort; there is no role for priestly mediators, and this would seem to inhibit any sort of congregationalism. We see, however, that the differentiation of the worshiper's role into two modes allows for a strong congregational emphasis.

What follows is an abstracted account of the rite as I saw it performed in 1990 with a special emphasis on the text. The focus of worship was a small metal image of the Tirthankar and a metal disc on which the siddhcakra had been inscribed.[12] These items were placed atop a stand that was stationed at the entrance to the main shrine at Mohan Bari. Participants sat in the temple's courtyard, with men to one side and women to the other (the standard arrangement). In front of this stand with the image was a low table on which five small flags had been placed in a row. Svastiks (executed in sandalwood paste) marked the positions at the foot of each flag where offerings were deposited as the ceremony progressed.

Parsvanath's Story

The puja of Parsvanath's five kalyanaks begins with the cyavan kalyanak , his descent from his previous existence as a god into a human womb.[13] The text for this sequence consists of three songs that recount Parsvanath's nine births prior to his final lifetime. This narrative centers on Parsvanath's relationship with Kamath, who is Parsvanath's transmigratory moral alter. Kamath's defects reverse Parsvanath's virtues, and Parsvanath's virtues provoke Kamath again and again into the gravest sins. The story of how this fateful relationship began is not covered in the text, but is well known to the rite's participants. Marubhuti (who will become Parsvanath in a later birth) and Kamath were once Brahman brothers. Marubhuti was a paragon of virtue who had accepted Jainism and spent his time in meditation and fasting. Kamath, much given to sensual pleasures, committed adultery with Marubhuti's wife. Marubhuti spied on the couple and reported Kamath's misdeed to the king. Kamath was punished, and Marubhuti was filled with regret. Marubhuti came to Kamath to beg forgiveness, and, while he was bowing, Kamath killed him with a stone.

It is at this point that the narrative begins. "Crooked Kamath was

attached to sensual vices," says the opening verse, "he killed his brother Marubhuti." As the text (which I summarize) continues, we learn how Marubhuti took his next birth as an elephant and was returned to the piety of his previous life by the king, who in the meantime had become an ascetic. Taking the form of a kukurt serpent (part snake, part cock), Kamath then murdered him again. Marubhuti was reborn as a god, while Kamath went to hell. In his next birth Marubhuti became a king named Kiranveg. He renounced the world, only to be murdered again by Kamath in the form of a snake. Marubhuti now became a god in the twelfth heaven, while Kamath descended to the fifth hell. In his next birth Marubhuti was a king named Vajnabh. He again renounced the world, and Kamath, in the form of a Bhil (a member of a particular tribe), killed him with an arrow. Marubhuti then became a god in one of the highest heavens, and Kamath descended to the seventh hell.

Marubhuti's eighth birth was announced by the fourteen dreams that herald the birth of a cakravartin (or a Tirthankar), and he became an emperor named Svarnbahu. This birth was decisive, for after renouncing the world and performing the bis sthanaktapasya[14] he acquired the karma that would result in a future birth as a Tirthankar (tirthankarpad nam-karm ). Wicked Kamath, this time in the form of a lion, murdered him again. In his next birth Marubhuti became a god in the tenth heaven, and Kamath fell once again to hell. As a god, Marubhuti worshiped Tirthankar images in Nandisvar Dvip (a continent, inaccessible to humans, where there are temples in which the gods worship Tirthankar images) and served ascetics. Although he experienced enjoyment, his mind remained detached; he was like the lotus, says the text, that remains separate from the slime in which it grows. Unlike other gods, the text observes, a Tirthankar-to-be does not grieve when he learns of his death six months before. He rejoices because he knows that after his human rebirth will come liberation. The narrative pauses here. It is time for the first offerings.

Meritorious action (punya ) and sin (pap ) are important themes in the story thus far. Virtue is rewarded by rebirth in heaven; sin brings the miseries of hell. The wretched Kamath's career is the mirror opposite of Marubhuti's. Drawn by his hatred into a transmigratory career of crime (of which we have not yet seen the end), Kamath repeatedly falls into hell. It should be noted, however, that even Tirthankars-to-be can suffer the pains of hell. During the twenty-seven births leading up to his Tirthankarhood, Mahavir did two terms in hell, one in the sev-

enth hell. There is, therefore, a higher point to the tale, which is that the value of world renunciation transcends mere questions of sin and virtue. Heaven's joys are transient (as are hell's agonies). Although his virtues bring him stupendous worldly and heavenly enjoyments, wise Marubhuti remains indifferent, and this is what brings him to final victory.

The text thus introduces us to a central problematic in the Jain view of things. Religious practice (such as this rite itself) generates that "good karma " known as "merit" (punya ). Merit brings worldly rewards (the world, of course, includes heaven). But no karma is ever really "good," and these rewards are of no ultimate value. Thus one must—even in their midst—strive to aim beyond them. The Tirthankar exemplifies what it means to succeed in this endeavor. This is a theme that we will encounter repeatedly in this book.

At the end of these verses comes the poet's signature line, and a short Sanskrit verse recapitulating the main themes of the preceding text, followed by a formula (a Sanskrit mantra ) of offering. The recapitulative Sanskrit verse and the offering formula are standard preliminaries to the offering itself. At this point a gong is sounded, and the required ritual actions are then performed by the puja principal or principals (in the observed case, a single individual). A small amount of water is poured on a folded cloth: this is an abbreviated bathing of the image. The image is then anointed with sandalwood paste. The leftmost flag is gar-landed, and incense and a lamp are proffered. A svastik is formed from rice (taken from the platter) atop the one already drawn on the table's surface in front of the flag. On this is placed a coconut to which a cloth and a currency note have been tied with a ceremonial string. In this context the coconut is called "sriphal ," and, according to informants, it stands for auspiciousness, for good results. Sweets and fruits are then arranged around the coconut. With this the cyavan kalyanak is complete.

Before resuming, it should be noted that the edibles and other offerings made in these sequences are never returned to the offerers. This point is exceedingly important and will be explored in greater detail later.

Next comes the janam kalyanak , the Lord's birth. The text resumes. Parsvanath is born in Banaras; his mother is Queen Vama, his father King Asvasen. "Blessed is the city of Banaras," the opening couplet proclaims; "blessed is king Asvasen / Blessed is the virtuous Queen Vama, because they obtained the Lord." The text then tells of how the queen experienced the fourteen auspicious dreams that always precede the

birth of a Tirthankar: first an elephant, then a bull, a lion, the goddess Sri, and ten other highly auspicious visions.[15] A reader of dreams pronounced that they heralded wonderful things to come.

These dreams are of crucial importance. Although the text does not elaborate the point, it is well understood that they have a double meaning. They indicate that the child-to-be will become a cakravartin , a universal emperor, but they also can be taken to mean that he will be a Tirthankar. This is a matter to which we shall return.

Lord Indra (one of the sixty-four kings of the gods, in this case the ruler of the first Jain heaven) then rose from his lion-throne and saluted the child-to-be as the "self-enlightened Lord, light and benefactor of the world." The Lord was born, the text says, on the tenth day of the dark fortnight of Paus. The fifty-six goddesses known as Dikkumaris performed chores associated with childbirth. The sixty-four Indras then took the infant to Mount Meru and there performed his birth ablution (abhisek ). At this point this portion of the text ends. The usual Sanskrit verse and formula of offering are repeated, and the gong is sounded. The ritual acts are performed exactly as before, but this time the garland, lamp, and other items are offered at the position of the second flag from the left.

The Lord's diksa , his initiation as an ascetic, comes next. The text continues, and the narrative now shifts to Parsvanath's childhood. He was beloved by the people. He possessed the three jnans of mati, srut , and avadhi .[16] He sucked nectar from his thumb. Youth and adolescence passed, and he married the princess Prabhavati. Wicked Kamath appeared again, this time as a fraudulent Brahman ascetic performing the five-fire penance. Having arrived at the scene with his mother, Parsvanath saw a cobra hiding in one of the pieces of burning wood. "Tell me how," he asked the ascetic, "austerities accompanied by violence can be fruitful?" He then removed a pair of half-burnt cobras from the wood (in other accounts only one snake is removed). He repeated the namaskarrnantra , and the now-enlightened cobras became the guardian deities Dharnendra and Padmavati.[17] Kamath fled, died, and became a demonlike being named Meghmalin.

The text now turns to the initiation. One spring season Parsvanath saw a picture of Neminath's wedding party, and his mind turned to thoughts of world renunciation.[18] The Lokantik gods urged him to renounce the world, to teach, and to redeem those who were capable of liberation. He gave gifts for a year. The gods and kings then took him to the garden named Asrampad, and there he fasted for three days and

obtained the fourth jnan (the mind-reading ability acquired by all arhats at the time of initiation). With three hundred men he took initiation, and the gods gave him his ascetic garb.[19] The gods celebrated the initiation kalyanak and went to Nandisvar to worship the eternal Tirthankar images there. The signature line is followed by the Sanskrit stanza and offering formula. The ritual actions are performed as before, but this time at the position of the third flag from the left.

Next is kevaljnan , the Lord's achievement of omniscience. The text resumes. The Lord wandered from place to place, totally devoid of attachments, and took his first post-fast meal in the house of a rich man named Dhan. He came one day to the forest named Kadambri, and there once again met Kamath, now Meghmalin. Meghmalin tried to break his concentration. He conjured up the forms of a lion and a snake, but the Lord was undisturbed. Clouds then thickened and surged, lightning cracked, rain fell like missiles, and the world began to flood. The water rose to Parsvanath's nose, but his concentration was still unshaken. The throne of Dharnendra began to shake, and by means of avadhijnan (clairvoyant knowledge) he saw his Lord's danger. He and Padmavati then saved Parsvanath from the flood. Here the text is referring to the famous incident, known to virtually all Jains, in which Dharnendra, aided by Padmavati, rescues the Tirthankar by raising him from the water on a lotus and protecting him from the pelting rainfall with his multiple cobra hoods (see Figure 2). Dharnendra then rebuked Kamath. Humbled at last, Kamath "took the shelter of Parsvanath's feet"; that is, he became Parsvanath's devotee.

The text continues. For eighty-four days the Lord remained an ascetic; on the fourth of the dark fortnight of the lunar month of Caitra (March/April), while under the dhataki tree, he obtained kevaljnan . He advanced through the gunasthans and cut the ghatikarmas . He manifested the eight pratiharyas (miraculous signs of Tirthankarhood). After the signature line of the final hymn come the Sanskrit verse and formula of offering. The ritual acts are performed, this time at the position of the fourth flag.

Fifth and last is the nirvankalyanak , the Lord's liberation (nirvan ). The previous kalyanaks have all had three songs; this time there are only two. The text resumes. The Lord sat and preached in the place of assembly of humans, gods, and animals (samvasaran ). His parents came to hear his teachings and took initiation themselves. Subh (Subhdatt) and his other chief disciples appeared. The Lord brought enlightenment to ascetics and nonascetics, men and women. The text now reiterates

Figure 2.

Parsvanath with Dharnendra and Padmavati. From

a framing picture obtained in Ahmedabad. Courtesy of Prem-

chand P. Goliya.

the story of his last lifetime: for thirty years he was a householder, and an ascetic for eighty-three days; he spent sixty-nine years, nine months, and seven days in the condition of kevaljnan . He knew he would live one hundred years. He spent his last rainy season retreat (caturmas ) on the peak of Samet mountain. Thirty-three ascetics were with the Lord; together they fasted for one month. On the eighth of the bright half of the lunar month of Sravan (July/August) he attained liberation. The gods came, their hearts filled with joy and sorrow; they celebrated the kalyanak with cries of victory.

The author signs, the usual verse and offering formula are repeated, and the ritual actions are performed, this time at the position of the fifth flag. This is the conclusion of the ceremony, except for a final sequence called kalas (in which participants toss colored rice and flower petals at the image and water is poured at the four corners of the ceremony's site) and two lamp offerings (arati and mangal dip ), which are standard exit-acts for all important rites of worship.

The Ideal Life

What is this rite about? Its performance is, in part, seen as a source of auspiciousness and benefit to those who participate in it. This is a theme to which we shall return in the next chapter. In its narrative dimension, however, it is concerned with the nature of worship-worthiness. The most worship-worthy of all beings is the Tirthankar. This is because he leads the ideal life, and Parsvanath's five-kalyanakpuja is, at its textual core, a celebration of such a life.

The rite tells us first of all that the ideal life has a transmigratory context. This is a point often missed in English-language accounts of Jainism in which attention is usually focused entirely on the Tirthankars' final lifetimes. To Jains, however, one of the crucial things about a Tirthankar is that his final lifetime is indeed his final lifetime, the last of a beginningless series of rebirths. It must be stressed that, from the Jain point of view, a lifetime considered outside the context of the individual's transmigratory career is meaningless. We shall consider this point in greater detail later in this chapter.

In conformity with hagiographic convention, the text recounts Parsvanath's previous births beginning with the lifetime in which he obtained "right belief" (samyaktva ). This is a crucial idea in Jainism. Jains say that once the seeds of righteousness have been planted, progress is always possible, no matter what the ups and downs in the meantime. An Ahmedabad friend once told me that if you possess right belief for as little time as a grain of rice can be balanced on the tip of the horn of a cow, you will obtain liberation sooner or later.[20] Therefore, even if one has little immediate interest in the ultimate goal of liberation or little sense of its personal gainability—which is in fact true of many ordinary Jains—one can still believe that one is on the right road if one has been touched by Jain teachings and if one has the necessary "capability" (bhavyatva ). How does one know who is on this path and who has this capacity? Such persons are, surely, among those who celebrate

the Lord's kalyanaks and who do so in the proper spirit of devotion and detachment from worldly desires.

Parsvanath's transmigratory career then takes a decisive turn. His destiny is fixed when he acquires the karma of a future Tirthankar two births before his final one. He has reaped the rewards of his virtues, but these he sees in the perspective of a fully realized detachment. The rite then draws our attention to his penultimate existence as a god. Other gods mourn their impending earthly rebirths. Not so the Tirthankar-to-be, for he regards the fall into a human body as an opportunity. This is a crucial matter, for it marks the separation of two possible paths. Divine and earthly happiness is the inevitable reward of virtuous action. This the Tirthankar-to-be achieves in abundance, but he is completely indifferent to it. His is another goal. Felicity is a shackle, albeit (as Jains frequently say) one of gold.

The text thus illustrates a choice, and in theory Parsvanath might have chosen differently. His virtues bear the fruit of material rewards. The highest of these is rebirth as a deity. But this he rejects. Parsvanath-to-be does not regret , as do others, his loss of this status and condition. By the time of his descent into Queen Vama's womb he has already attenuated his attachments to the world and his basic detachment is secure.

The fourteen dreams that precede his birth are emblematic of the parting of the two ways. As noted, the dreams can be interpreted as foretelling the birth either of a universal emperor or of a Tirthankar (Dundas 1992: 31-32; Jaini 1979: 7). A universal emperor embraces the entire world—one might even say devours it. The Tirthankar rejects it utterly; the potential conqueror of all thus becomes the renouncer of all. The rejection occurs with his initiation, and it is significant that before initiation he gives (as do all Tirthankars) gifts for a year—a dramatic and complete shedding of his wealth and of the world. Kingly largess and the ascetic's giving up are, at this moment, different aspects of the same thing. This idea is basic to Jain ritual culture, as we shall see. Then follow omniscience and the inception of his teaching mission. Unlike others who attain liberation, the Tirthankar, as the text tells us, is self-enlightened; he assists others on the road to liberation, but requires no assistance himself.

Having taught, he attains final liberation. His links with the world are severed entirely. Now, in completely isolated and omniscient bliss, he abides eternally in the abode of the liberated at the top of the universe.

The Cosmos

We have seen that the text of Parsvanath's five-kalyanakpuja places great emphasis on the wider transmigratory context of Parsvanath's Tirthankarhood—his journey through different states of existence in different regions of the universe. This is one of the most obvious facts about the rite: that it situates itself in relation to a cosmos far wider than the place and time of Parsvanath's last birth. Within the framework of the rite, it is his cosmic situation that renders his final lifetime intelligible. A certain vision of the cosmos is therefore an element in the ritual culture within which the rite occurs. This is a vision in which the radical asceticism represented by the Tirthankar—asceticism that culminates in his complete disappearance from the world of acts and consequences—is a reasonable response to existence.

The key to this vision is magnitude. If we supplement the rite's text with other sources, as I now propose to do, we discover that the Jain cosmos is a place of very large numbers. It is a stupendous vision in which, some would say, we see the numerical and metrical imagination run riot. The point of the vision, however, is not simply metrical; rather, its purpose is to illustrate the difficulty of attaining liberation. The cosmos, enormous in extent, swarms with forms of life, most of which are highly vulnerable to inadvertant or deliberate violence. Within this vast system, the opportunity to acquire a human body, which is the only body in which liberation is possible, is vanishingly small. The numbers in question are deployed in three domains: space, time, and biology.[21]

Space

The Jain cosmos is a multi-tiered structure divided into three "worlds" (loks ): a world of the gods above, a hell below, and between them a thin terrestrial world where (among others) human beings dwell (Figure 3). At the very top is a small fourth region, resembling a shallow depression, which is the abode of liberated souls (siddh sila ). Running like a shaft from top to bottom is a zone called the tras nadi , so named because multisensed beings (tras ) cannot exist outside it. The entire structure is fourteen rajjus high. The standard unit of distance in Jain cosmography is the yojan , which equals about eight miles. A rajju (rope) is equal to "uncountable" yojans .[22] Mt. Meru, which is 100,000 yojans (800,000 miles) high, is depicted on Jain maps as the merest bump in comparison with the whole structure. This vast cosmos, with its multiple layers and enormous internal volume, is the venue of the

Figure 3.

The Jain cosmos. A simplified version of a

book illustration (Santisuri 1949: unnumbered page)

Note the shaft-like tras nadi extending from top to

bottom. The horizontal lines mark the fourteen rajjus

of the structure's height. The levels of hell correspond

to the rajju lines below the terrestrial world; the vari-

ous heavens are distributed within the upper half of

the tras nadi.

drama of the soul's bondage and liberation. Like a gigantic sealed aquarium, it is completely self-contained: Nothing enters, nothing leaves. Within it is an infinite (anant ) number of beings (jivs ) who cycle and recycle from death to birth to death again. Except for the liberated, this wandering from existence to existence is eternal, for the cosmos was never created nor will it ever cease to be.

Humanity's physical surround is the terrestrial world, which is a flat disc with Mount Meru at its center[23] Here, and only here, are to be found human beings and animals. At the middle of this disc, and serving as Mount Meru's base, is a circular continent called Jambudvip, which is subdivided into seven regions separated by impassable mountains. The most important of these regions are Mahavideh, Bharat, and

Airavat. Mahavideh is a broad belt running east and west across the continent and is divided into thirty-two rectangular subdivisions. At the extreme south and north of the continent are, respectively, the much smaller regions of Bharat and Airavat. Bharat is the South Asian world, and the sole region physically accessible to us.

Surrounding Jambudvip is a series of concentric oceans and atoll-like circular islands continuing outward to the edge of the disc. These are said to be "innumerable" (asankhyat ), which means that although there is an actual limit beyond which there is simply empty space, the number of islands and oceans cannot be counted. The first two islands are divided into regions representing radial extensions of the seven regions of Jambudvip: Here, too, we find Mahavidehs, Airavats, Bharats, and so forth. Humans dwell in all of the regions of the first island, but it is possible for humans to live only in the inward-facing zone of the second island, which is separated from the outward-facing zone by a range of mountains.[24]

The most important feature of the terrestrial world is not its rather complicated physical geography (of which my brief account gives little true idea) but its moral geography. A portion of the habitable lands of Jambudvip and of the first two concentric islands is known as bhogbhumi , "the land of enjoyment." Humans living in these regions exist in a state of continuous enjoyment without effort or struggle; subsistence is provided by trees that magically fulfill wishes, and premature death is unknown. Because asceticism cannot flourish in such an environment, Tirthankars do not appear in these regions and liberation is not possible. Contrasting with bhogbhumi are the areas known collectively as karmbhumi , "the land of endeavor," in which our region is included. In these regions it is necessary for humans to earn their livelihoods through work, and premature death is possible. Because such an environment is conducive to reflection and asceticism, liberation is possible in this zone, and Tirthankars are born here.

The terrestrial world is dwarfed by the regions above and below. Towering above is the "world of gods" (devlok ), which is the destination of those who have lived virtuous lives.[25] The areas actually inhabited by deities are contained within the shaft-like tras nadi . There are twenty-six separate paradises in all, organized in a series of levels extending up to the top of the cosmos just below the abode of the liberated. Between the lowest heaven and the terrestrial world is a gap; here planetary and stellar bodies (the abodes of the jyotisk deities) move in stately circles around the summit of Mt. Meru. Below the terrestrial

world, and extending downward as far as the heavens rise above, is the region known as hell (narak ).[26] This is where those who have committed sins must suffer the consequences. There are seven levels of hell, and the lower the hell the more severe the punishment.

Among the more striking features of this cosmos is its sheer size. By comparison with the upper and lower worlds, the terrestrial world is tiny. The entire cosmos is often represented as a standing human figure with the terrestrial world as its pinched waist. And yet even if the terrestrial disc is viewed within a reduced frame of reference, it too turns out to be vast. The diameter of the central area of the terrestrial world—that is, the world within the circle of mountains dividing the second circular island into habitable and nonhabitable zones—is 4,500,000 yojans , which (if the precise calculation is relevant) is roughly 36 million miles. The diameter of Jambudvip is 1000,000 yojans (800,000 miles) and the north-south dimension of Bharat is roughly 525 yojans (about 4,200 miles).

Taken together, these figures and calculations provide a basis for a certain conception of one's situation in the world. By comparison with one's immediate surroundings, Bharat is vast. But Bharat is but a tiny bite off the edge of the world-island to which it belongs. Inconceivably vaster than this world-island is the world-disc. But the world-disc itself is but a thin wafer in a cosmos that is a towering hierarchy of unimaginable dimensions. And everywhere (as we shall see) this cosmos teems with beings. Very small then—inconceivably small by comparison—is an individual's own niche in the cosmos.

Time

According to the Jain vision of things, in the karmbhumi regions of Bharat (our region) and Airavat, time moves through repetitive and very gradual cycles of moral and physical rise and decline. During the ascending half-cycle the human life span lengthens, body size increases, and the general level of happiness increases; these trends are reversed in the half-cycle of decline. The cycles are immensely long. According to one version,[27] a complete cycle lasts for a period of time equal to twenty korakorisagars . Korakori is a numerical expression equaling ten million multiplied by ten million, so by this reckoning an entire cycle takes 2 × 1015 sagars . A sagar (or sagaropam ) is a unit of time measurement. The same source (see also J. L. Jaini 1918: 90) asserts that one sagar equals one korakori , multiplied by ten, of units

called addhapalyas , and an addhapalya equals "innumerable" uddharapalyas , each of which in turn contains "innumerable" vyavaharapalyas . A vyavaharapalya equals the time it would take to empty a circular pit with a diameter and depth of one yojan (8 miles) of fine lamb's hairs if one hair were removed every 100 years.[28] The point of these abstruse and fantastic calculations is, of course, to emphasize the nearly inconceivable vastness of the periods of time portrayed.

Each half-cycle is subdivided into six eras and each era is named according to how "happy" (sukhama ) or "unhappy" (dukhama ) it is (ibid.: 89). An ascending half-cycle thus evolves from dukhama-dukhama (severely unhappy) through dukhama (unhappy), dukhama-sukhama (more unhappy than happy), sukhama-dukhama (more happy than unhappy), sukhama (happy), to sukhama-sukhama (extremely happy) (renderings partly from P.S. Jaini 1979:31). The declining cycle is the reverse of this. We (in Bharat) are currently in the fifth age (often called the pañcam kal ) of a declining half-cycle. When a descending half-cycle begins, all human wants are effortlessly satisfied by wish-fulfilling trees, and human beings attain an age of three palyas (presumably addhapalyas ) and a height of 6 miles. By contrast, the last age is a time of extreme discomforts and lawlessness; miserable, dwarfish, with a height of one and one-half feet, humans live a mere twenty years. In a declining cycle such as ours, Tirthankars exist only during the fourth age (the first Tirthankar appearing at the very end of the third), and it is only during this period that liberation is possible. During the first three ages the general happiness discourages ascetic exertion, and during the last two ages the misery is too great. Our current fifth age began just after Lord Mahavir (the last Tirthankar of our half-cycle) left the world; it will last only 21,000 years.

These cycles, however, do not occur in all regions of the terrestrial world. The most significant exception is Mahavideh, half of which is karmbhumi . This means that there are Tirthankars active at the present time in that region.

The social and cultural world we know was the creation of Rsabh, the first of the twenty-four Tirthankars of our declining half-cycle.[29] As P.S. Jaini (1979: 288) points out, Rsabh occupies the functional niche of a creator deity in a tradition that denies creation. Prior to his advent, the world was a precultural paradise.[30] Because of the magical wish-fulfilling trees, toil was nonexistent. Old age and disease were unknown. Religious creeds did not exist. There was no family, no king or subjects, no social organization. As just noted, humans were 6 miles tall

and their lives were eons long. Born six months before their parents' death, these extraordinary beings (called yugliyas ) came into the world as mated sibling pairs. Each pair lived as a couple after puberty, and in time produced two similar offspring. In uncanny parallel with the theories of Lévi-Strauss and other anthropologists, the Jains see presocial humanity as humanity without the incest taboo.

With the passage of the first three eras conditions deteriorated. The magical trees began to disappear and this resulted in shortages of food and other necessities. This led to the development of anger, greed, and conflict. Because of the crime and disorder, the frightened people met together and formed small family groups (kuls ), and set persons of special ability in positions of authority. Here is Hobbes in a Jain guise. These individuals were called kulkars , and by establishing property rights and a system of punishments, they were able to maintain order as paradise dwindled away. The last of the kulkars was named Nabhi,[31] and he was the father of Rsabh.

Rsabh was the inventor of society, polity, and culture in our half-cycle of cosmic time. He was the first king, made so by the twins because of the troubles then occurring. He introduced the state (rastra ), the enforcement of justice by punishment (dandniti ), and society (samaj ) itself (these terms are from Lalvani 1985:31)[32] He established the system of varnas , the ancient division of Indian society into functional classes.[33] He also taught such necessary arts as farming, fire-making, the fashioning of utensils, the cooking of food, and so on. His was also the first nonincestuous marriage, which established the current system of marriage. In the end he abandoned the world and became the first Tirthankar of our half-cycle of cosmic history. He was also the first to receive the dan (merit-generating gift) of food from a layperson, which in this case was sugar cane juice. So important was this event that Jains commemorate it in a calendrical festival (aksaytrtiya ).

With Rsabh's advent, our corner of the world became redemptively active. He was the only Tirthankar of the third age; after him, in the fourth age, came the remaining twenty-three Tirthankars Of our current declining half-cycle. Each promulgated the same teachings and left behind the same fourfold social order of monks and nuns, laymen and laywomen. The penultimate was Parsvanath, with whose rite of worship this chapter began, and the last was Lord Mahavir. Soon after Mahavir's departure the window of opportunity for liberation closed.

The history of the twenty-four Tirthankars invests what would otherwise be a featureless timescape with moral and soteriological

meaning. There is no beginning or end to the cosmic pulsations of the Jain universe, and in this perspective the face of time is blank. But within the cycles the passage of time can be converted into a significant narrative, one that has a direct bearing on the nature of the world experienced by men and women at the present time. The era of the Tirthankars thus seems to mediate between timeless eternity and the world that men and women know: The totally repetitive periodicity of the five kalyanaks belongs to eternity; the individuation of the specific careers of the twenty-four Tirthankars belongs to the particular history of our world and era.

Mahavir's departure inaugurated the history of the Jain tradition itself, established by Mahavir's followers. The ultimate locus of the sacred for the Jains, the Tirthankar as a generic figure, is no longer present in the world.[34] In the aftermath of their era, therefore, the task is to maintain some kind of contact with their presence as it once was. They are gone—as we have seen—utterly. But although the beneficence (kalyan ) intrinsic to their nature exists no longer in embodied form, it can be transmitted from generation to generation by means of the lines of disciplic succession that link lineages of living ascetics with Lord Mahavir. Their teachings also remain, although we possess only an incomplete version. Although their kalyanaks no longer occur in our world, these events can be (as we have seen) evoked through ritual. And of course the social order they established—the fourfold order of Jain society—endures still.

Biology

The Jains have created a complex system of biological knowledge. It is a system that includes concepts of physiology, morphology, and modes of reproduction, but its main focus is taxonomy. It should not be thought of as a system of scientific analysis. Its basic motivation is soteriological, and the system may be seen as a conceptual scaffolding for the Jain vision of creaturely bondage and the path to liberation.

The beings of the world (jivs ) are divided into two great classes, liberated (mukt ) and unliberated (samsari ). Liberated beings are those who have shed all forms of karmic matter, and unliberated beings are those who are in the bondage of karma .[35] In turn, unliberated beings are divided into two great classes: beings that cannot move at their own volition (sthavar ) and beings that, in order to avoid discomfort, can move about (tras ).[36] The beings of the sthavar class possess only one

sense, the sense of touch, and are of five types: 1) "earth bodies" (prithvikay ) that inhabit the earth, stones, and so on; 2) "water bodies" (apk ay ) that inhabit water; 3) "fire bodies" (teukay or tejkay ) that live in fire (and electricity); 4) "air bodies" (vayukay ) that inhabit the air; and 5) plants (vanaspatikay ).

Plants come in two general types: pratyek , in which there is one soul per body, and sadharan , in which there are infinite (anant ) souls in a given material body. The sadharan or multiple-souled forms of plant life are, in turn, of two types: "gross" (badar ) and "subtle" (suksam ). The gross varieties include such common root vegetables as potatoes, carrots, onions, garlic, and yams, and this taxon, therefore, is extremely important from the standpoint of dietary rules. Because potatoes and similar vegetables harbor tiny forms of life in infinite numbers, they are—in theory—forbidden to Jains.[37] The ban on the eating of root vegetables is one of the principal markers distinguishing Jain vegetarianism from that of other vegetarian groups in India. The plant category also includes tiny beings, infinite in number, called nigods .[38] They are the lowest form of life and exist in little bubble-like clusters that fill the entirety of the space of the cosmos. They live a short time, perish, and then take rebirth as nigods again (with some exceptions, as we shall see). They are a teeming sea of invisible life everywhere around us, even within our bodies.

Tras beings are classified on the basis of the number of sense organs they have. The viklendriy class, consisting of beings of two to four senses, opposes the pañcendriy class, consisting of beings with five senses. Two-sensed animals have taste and touch; three-sensed animals add smell; four-sensed animals add vision; and five-sensed animals add hearing. A somewhat different principle of animal classification is based on the manner of giving birth. Those born from the womb (and this includes eggs) are called garbhaj . Beings called sammurchim are born by means of the spontaneous accretion of matter into a body. All beings of fewer than five senses are born this way, as are some five-sensed animals and human beings.

Coexisting with (and consistent with) the above scheme is yet another system of classification, and in many ways this is the most important of all. This is the system of the four gatis , the four "conditions of existence." These four categories are: hell-dwellers (naraki ), animals and plants (tiryañc ),[39] humans (manusya ), and deities (dev ). They are ranked on the basis of the relative happiness (sukh ) or sorrow (dukb ) experienced by the beings within them.

The most miserable of all beings are the hell-dwellers. They exist in perpetual darkness and suffer from unrelenting hunger, thirst, and extremes of heat and cold. They are tortured in various ingenious ways by demon-like beings who perform this function. The punishment is often of the punishment-fits-the-crime variety. Picture books exist in which the punishments for various sins are depicted in vivid and rather disgusting detail, a sort of pornography of punition.[40] Hell-dwellers take birth (as do the gods) by means of instantaneous creation, and their terms of punishment are eons long. An Ahmedabad informant once told me that hell-beings remember their torments after they are reborn as humans, which—he said—is why babies cry. He then went on to say that the parents give the child a doll to stop the crying, and the child clings to it and says, "mine! mine! mine!" Then, he continued, at the age of twenty-one or so "they give you a bigger doll, and the same thing happens." The result is attachment to family and other worldly things, and so the cycle goes on.

The animals and plants (tiryañc ) experience somewhat less misery than hell beings do, or at least this seems to be true of five-sensed animals. However, birth anywhere in the tiryañc category is extremely undesirable. Their natural place of habitation is the world-disc, but they can live in many areas barred to human beings.

Human beings experience more happiness and less sorrow than those in the tiryañc category. As noted already, humans occupy only the restricted central area of the world-disc; they are distributed, of course, between the two moral zones of karmbhumi and bhogbhumi . The humans in bhogbhumi are born as twins of the same sort that exist in our world during the paradisaical age; their lives are spent in sensuous enjoyment, and liberation is impossible for them. Humans can be either womb-born (garbhaj ) or born by spontaneous generation (sammurchim ). The latter are generated from various impurities (such as excrement, urine, phlegm, or semen) produced by the bodies of womb-born humans. They are without intelligence and cannot be detected with the senses; their bodies measure an "uncountably" small part of a finger's breadth. They die within one antarmuhurt (forty-eight minutes) without being able to develop the full characteristics of a human body.[41] Certain rules of ascetic discipline are based on the injunction to avoid harming these beings. For example, after eating, some ascetics and extraorthoprax laymen drink the liquid residue from washing their hands and plates or bowls. This is to prevent the spontaneous generation of millions of little replicas of themselves, for whose deaths they would

then be responsible, in the meal's remains. Just as the category of multiple-souled plants invests Jain vegetarianism with a distinctive character, this category provides the basis for certain distinctive features of Jain asceticism.

The truly crucial fact about human existence, however, is that liberation is possible only in a human body. As we know, liberation is not possible for all humans, but it is possible only for humans. This is a fact with momentous consequences, as we shall see in the next chapter.

The gods and goddesses are, in some ways, mirror images of the hell-beings. Hell-beings are being punished for their sins; the gods and goddesses are being rewarded for their virtuous acts in previous existences. The question of the cosmic functional niche of the gods and goddesses will be addressed in the next chapter. For now it is sufficient to note that, as are the hell-dwellers, the gods and goddesses are stratified. The lowest are the bhavanvasi s, "those who dwell in buildings," who live in the uppermost of the seven hells but are not subjected to hellish torments. Residing in an intermediate level between the uppermost level of hell and the earth are deities known as vyantar s who inhabit jungles and caves. They can help human beings, but can be malicious, too. The jyotisk deities (planetary deities) dwell in the region between the earth and the heavens above. They belong to two basic categories, moving and stationary.

The most important deities are the vaimanik s, so named because they inhabit heavenly palaces (viman s) of various kinds. They are divided into two basic types. Lowest are the kalpopapan s, those who are born in paradises (kalpa s). Residing in palaces above the kalpopapan deities are the kalpatit deities (without kalpa s), who are of two kinds: the graiveyak s, who dwell in nine palaces above the topmost of the heavens of the kalpopapan deities, and the anuttar s, who live in five palaces higher still. The kalpopapan deities perform the celebrations of the Tirthankars' kalyanak s. They also live in organized societies in which there are kings, ministers, bodyguards, villagers, townsmen, servants, and so on. The kalpatit deities do not participate in rituals and are not socially organized. Goddesses are found dwelling only in the first and second heavens of the kalpopapan deities and below, although they may visit higher heavens. In these lower regions the gods have sexual relations; at higher levels, sexual relations become progressively etherealized: from mere touch, to sight, to hearing, to thought, and finally to no sexual activity at all.[42]

The Indras are the kings of the gods. There are sixty-four of them in

total: twenty who rule the bhavanvasi s, thirty-two for the vyantar s (and a subcategory known as van vyantar s), two for the jyotisk s, and ten for the twelve paradisaical regions. As we shall see in the next chapter, the Indras (and Indranis, their consorts) are symbolically central to ritual action among Jains.

Rules

The Jain universe might be likened to a three-dimensional board game. The board is samsar , the world of endless passage from existence to existence.[43] The playing pieces are infinite in number and are, subject to the rules of the game, free to move anywhere on the board. The object of the game is to leave the board. The game has no beginning or end; it has been going on from beginningless time (anadi kal se , as Jains always say) and will continue for an infinite time to come (anant kal tak ). Nor does it reflect the purposes of some divine creator; there is no rhyme or reason to it—the game simply is. Most player/pieces are not even aware of the game, to say nothing of the possibility of winning; they merely wander "without a goal" (laksyahin ) from existence to existence, leaving pain and havoc in their wake.

The various taxa of living things are the stopping places of player/ pieces between moves; moves occur at the moment of death. There are rules of play (often called sasvat niyam , "eternal rules," in the materials I have seen) determining which moves are possible and which are not. The human and tiryañc classes share one critical feature: After death, humans and subhumans can be reborn in any class at all. They can return to their previous classes, or they can switch from tiryañc to human, or vice-versa. Or, on the basis of sin or merit, they can ascend to heaven or descend to hell, and it should be noted that this is true of animals as well as of humans.[44] By contrast, the divine and hellish classes are one-stop existences. Gods and hell-beings must be reborn either in the human or tiryañc class.

These various rules of play result in a game with certain general features. Victory, which is moving off the board of play, is extremely difficult to achieve. Even to have a chance at winning, one must first take birth in the human class, and this in itself is hard to do. Forward and upward progress is hard; falling backwards from the goal is easy. There is no opting out of the game. The game goes on eternally, and, short of victory, there is no way at all to discontinue play.

Cosmos as Pilgrimage

The soul's career in the cosmos is sometimes likened to a pilgrimage. A good example of the use of this metaphor is to be found in a book (Arunvijay, n.d.), put into my hands by a Jaipur friend, consisting of a collection of rainy season discourses given by a Tapa Gacch monk named Arunvijay.[45]

The soul, he says, is on a pilgrimage through the cosmos (a samsar yatra ) ,with the final destination being liberation. His account begins with the nigod , beings who have not yet begun the pilgrimage. Infinite in number and packed into every cranny of the cosmos, these tiny beings mostly just wink from one identical existence to the next. The nigod s, he says, are a kind of "mine" (khan ) or reservoir of souls, infinite in extent and inexhaustible. To begin the pilgrimage, a soul must leave this condition; only then does a soul enter the "dealings" (vyavahar ) of samsar . Can a nigod leave this condition by means of its own effort? No, says Arunvijay. It is a law of the cosmos that in order for one nigod to leave that condition, one soul in the universe must attain liberation. Given the vast number of nigod s and the relative infrequency of liberations, it follows that this is an extremely rare event, and that we—those of us now in a higher condition—are fantastically fortunate even to have left the condition of nigod .

Having left the status of nigod , he says, the soul enters various existences as badar sadharan vanaspati (coarse vegetable bodies that live together in infinite numbers in a single plant or portion thereof) and finds itself packed within masses of similar souls in the form of moss on a wall, a potato, or the like. It then takes birth as various kinds of earth and water bodies before graduating upward to the status of pratyek vanaspati (that is, the vegetable bodies that live one to a plant or portion thereof). It then goes on to inhabit air bodies and fire bodies. In this way the soul takes "uncountable" (asankhya ) births among the one-sensed beings.

Arunvijay says that the soul progresses because of the accumulated effect of merit resulting from virtuous actions performed in various births. Exactly how merit is generated by the activities of such humble beings he does not explain, and his overall characterization of the soul's destiny does not emphasize ethical retribution. Rather, the image he stresses repeatedly is the "wandering" (paribhraman ) of the soul. His favorite metaphor is that of the ox tied to an oil press. The wretched beast goes round and round in a circle (the four gati s); he is blindfolded,

and has not the faintest idea of where he has been or what his destination will be.

The pilgrimage continues. The soul takes "uncountable" births as it advances from two to four-sensed bodies. But it can also regress and even fall back into the one-sensed category again. In the end the soul may at last enter the category of five-sensed beings. It now spends countless years in this class. It must take birth as every form of water beast, then every kind of land animal, then all the varieties of birds. It takes "violent births" (himsak janam s) in the form of such animals as lions or tigers. As a carnivore it commits the sin of killing five-sensed creatures, and now it descends into hell.[46] The soul spends eons (sagaropanm s of years) in hell, and moves back and forth between hell and the tiryañc class many times. It even falls back into the four-, three-, two-, and one-sensed classes yet again. Eons more pass. And then progress resumes.

At long last, after infinite existences from beginningless time, the soul/pilgrim enters a human body. Alas, it sins and falls into hell, and from there takes birth all over again in the sub-five-sensed classes. As a result of truly fearsome (bhayankar ) sins commited as a human, the soul can even fall back into the condition of nigod . How often, our author exclaims, has the soul gone downward and how far it has fallen! Our soul/pilgrim may also become a deity on the basis of merit earned by deeds. From this condition, however, it must return, and Arunvijay says that it may well fall all the way down to the lowest classes of life again. These transformations will occur again and again. The soul/pilgrim goes through the four gati s, the five jati s (classes of beings with from one to five senses), and the entire 8,400,00 kinds of births that exist. This is the nature of the cycle (cakra ) of the soul's great pilgrimage through the cosmos. And there is more. Arunvijay reminds us that not only have we all been through this cycle, but we have been through it an infinite number of times.

What is Arunvijay's main point?[47] Almost everything he says converges on one fundamental assertion, namely that one's birth in a human body should not be wasted.[48] This reflects the ascetics' view of things, a view that exists as a perpetual rebuke to the more comfortable lay view that routine piety is enough. It is possible, he says, for human births to be repeated; in theory it is possible to have seven or eight in a row. But this is very difficult and requires an immense amount of merit. Human birth is "rare" (durlabh ) and in this vast cosmos very difficult to obtain. Sin is so easy, and the sins of one life can pursue you through

many births. Not only will sins send you to hell, but they will result in many births in the classes of two- to four-sensed creatures after you have emerged from below. Arunvijay reflects at length on the sin of abortion, and it is significant that, in his eyes, part of the horror of abortion is that it cuts the newly incarnated soul off from the possibility of a human existence.

His conclusion is that one must set a "goal" (laksya ) of release from the cycle of rebirth in the classes of living things. The contrast is between one who has such a goal and those who are "without a goal" (laksyahin ) .Those who are without a goal wander blindly and aimlessly. You have sinned an infinity of times, but now you have gotten the Jain dharm (Jainism). If you set the goal of release, he says, then it is easy to get rid of sins. What is needed is a full effort in spiritual endeavor. This is the real point of everything he has said. He is not much interested in the whys and wherefores of the wandering soul's entry into one kind of body or another. More important is the sheer scale of things. The soul takes many, many births—infinite births—in its endless wanderings through this vast cosmos. At long last has come the opportunity for deliverance, and this opportunity must not be allowed to slip away.

Arunvijay uses this vision of the soul's pilgrimage to reinforce the plausibility of central Jain values. Large numbers abound: uncountablities and infinities. The universe is inconceivably vast in size. The times-cape is infinite in extent. The taxonomic system is enormous and labyrinthine. The potential for doing harm to other beings is boundless. Liberation is possible only in a human body, and human bodies are hard to get. The zone of human habitation is tiny by comparison with the cosmos as a whole, as is the human taxon by comparison with the teeming multitudes of other forms of life with which the cosmos is filled. Indeed, even a human body is not in itself enough, because liberation is actually available during the merest sliver of time in comparison with all of time. And even in eras and places where Jain doctrine can be heard, not everyone hears it. Here, then, is the pilgrim at last in human form and in contact with Jain teachings. Lucky is such a pilgrim, and so valuable an opportunity must not be wasted.

Arunvijay's main concern is not with proselytizing asceticism. His primary goal is to raise the general level of piety of his lay audience. But the vision he projects is one that places a context around the core values that inform the text of Parsvanath's five-kalyanak puja . Ascetic withdrawal is the central meaning of Parsvanath's last life. The only truly

rational and morally defensible response to this cosmos is the most radical withdrawal from it. This is not the way most Jains live, but it is a constant undertow in Jain religious life, and one that creates strains and ambivalences. It cannot be ignored. How could it be, when it is dramatized on a daily basis by living ascetics?

Living Ascetics

Perhaps the first thing that should be said about Jain sadhu s and sadhvi s, monks and nuns respectively, is that they are not hermits. Indeed, in some ways the very opposite is true. Jain ascetics—particularly ascetics of consequence with lay followings—are public persons, and to be in their presence is to be in the center of a more or less constant hubbub. In the midst of the coming and going it is sometimes hard for the inquiring field researcher to get a word in edgewise. This life is not reclusive, and in fact it cannot be. Jain ascetics are totally dependent on the laity for every physical need; they cannot even prepare their own food. Among many other things, this means that ascetics and laity must come into constant contact among the Jains. Nor does the tradition define the ascetic's role as socially exterior. Readers will recall that every Tirthankar reestablishes the fourfold order of Jain society—the caturvidh sangh —which consists of monks and nuns, laymen and laywomen. Ascetics are obviously not householders, but they are nonetheless included in a wider social order.[49]

Although the primary focus of my research was the religious life of lay Jains, I was constantly being urged to consult ascetics. The reason for this is that ascetics are regarded by the laity as the sole true experts on Jain matters, a confidence not always well placed. While I was in Ahmedabad it was easy to meet both monks and nuns. It was the caturmas season, which meant that ascetics were in permanent residence, and the Tapa Gacch, the ascetic lineage dominant in Ahmedabad, is large. It was more difficult to meet monks in Jaipur, even during caturmas , for the simple reason that there are very few monks belonging to the Khartar Gacch, the image-worshiping ascetic lineage dominant in that city. As a result, monks were usually not present at all, although I encountered them from time to time. I did have the privilege of meeting many Khartar Gacch nuns in Jaipur, who were almost always present in the city. During the course of the year in Jaipur I had also had numerous conversations with monks belonging to the flourishing, nonimage-worshiping Terapanthi sect. Most of my image-worship-

ing friends held the Terapanthi ascetics in high esteem and saw nothing untoward about my contact with them. A well-known Digambar muni was also kind enough to allow me to spend a lot of time in his presence. This was a valuable source of comparative data on lay-ascetic interactions, especially in the crucial area of food.

The cultural personae presented by Jain ascetics is an amalgam. At one level they are personal exemplars. Here, their very existence suggests, is the kind of life one ought to want to lead. At another level they are the tradition's teachers. They give discourses, sometimes learnedly and sometimes not. Many lay Jains develop intensified relationships with a particular ascetic whom they regard as their guru (religious preceptor).[50] Jain ascetics frequently admonish and scold lay Jains for laxity in their behavior. I have been told that some lay Jains avoid contact with ascetics for fear of being asked awkward questions about their diet. They also instigate fasting and other religious/ritual behavior. Indeed, a layperson must make a vow before an ascetic (or in front of a Tirthankar-image if no ascetic is available) before undertaking ascetic practices such as fasts; without such a vow the exercise will be without results.

Ascetics are also, in their persons, objects of worship. This cannot surprise us, for Jains, as we know, worship ascetics. Although the namaskar mantra , the all-important formula with which this chapter began, singles out the Tirthankars as foremost among the worship-worthy, it also includes living ascetics, sadhu s (and by extension sadhvi s) .When Jain friends urged me to take my questions to ascetics, the content of what they might say was, perhaps, less important than the fact that they were the ones who would be saying it. After all, living ascetics participate in the sacredness of the Tirthankar, though at a great remove, and any interaction with them necessarily falls in the paradigm of worship.

Organization

According to a survey of rainy season retreat locations for the year of my research in Jaipur (B. Jain 1990: 62), in 1990 there were 6, 162 ascetics (1373 monks and 4,789 nuns) among image-worshiping Svetambar Jains. The Sthanakvasis had a total of 2,738 (532 monks, 2,206 nuns), and the Terapanthis had 719 (157 monks, 562 nuns) (ibid.). Digambar ascetics are very few by comparison with the Svetambars. According to the same source, in 1990 there were only 225 muni s and

130 aryika s (nuns who, unlike Svetambar nuns, do not take full vows), giving a total of 355 Digambar ascetics (ibid.: 63).