| • | • | • |

“One Hundred Days That Changed the World”

Nasser 56 is the brainchild of the veteran scenarist Mahfuz ‘Abd al-Rahman in collaboration with Egypt’s leading dramatic film star, Ahmad Zaki, who plays Nasser, and the veteran television director Muhammad Fadil. Originally intended as one of a series of hour-long dramatic biographies of Egyptian luminaries for television, each figure to be played by Zaki, the project blossomed into a full-length feature film on a grand scale.[1] Produced by the state-owned Egyptian Radio and Television Union (ERTU), the film was three years in the making, from initial conception to preview release in July 1995. Key portions were shot on brand-new outdoor sets at the 6 October Media Production City, the $300 million project designed to reinvigorate the flagging Egyptian film industry and maintain Cairo’s virtual monopoly on Arab television production (Khalil 1996a; Saad 1996). The film then sat another full year, “frozen” is the word used by its creators, before its release in early August 1996.

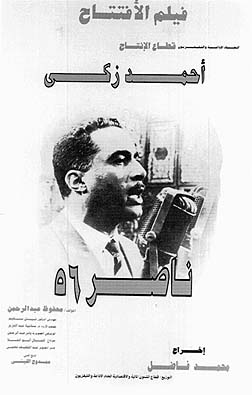

Fig. 1. Ahmad Zaki as Gamal Abdel Nasser; announcement for the official preview of Nassar 56 at the opening of the 1995 Television Festival. Courtesy of Mahfuz ‘Abd al-Rahman.

[Full Size]

Nasser 56, trumpets its ad, covers “one hundred days that changed the world.” The actual span is 106 days, from June 18, 1956, Evacuation Day, until November 2, several days after the outbreak of war. The film opens with Nasser taking down the Union Jack; it closes with a famous speech from the minbar of al-Azhar Mosque. As bombs fall around Cairo, Nasser proclaims that Egypt will fight on and never surrender. Much of the action focuses on political deliberation among Egypt’s leadership, formulation and implementation of the secret plan to secure the canal as Nasser addressed the nation from Alexandria on the night of July 26, and the subsequent political maneuvering of Nasser and his colleagues to defuse a crisis they cannot believe is escalating. Other well-known historical faces appear in subsidiary roles, among them military comrades Anwar Sadat, ‘Abd al-Hakim ‘Amr, Salah Salim, Zakariya Muhyi al-Din, ‘Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi, and Sami Sharaf and civilian associates Fathi Radwan and Mahmud Fawzi. More prominent supporting figures, such as the chief canal engineer, Mahmud Yunis, and his colleagues, are less familiar to many Egyptian viewers. There are no Egyptian villains in the piece, save for a small, rather pathetic group of old-regimistes who petition Nasser to resign in the wake of the tripartite attack.

The film was shot in black and white to effect a newsreel feel. In the opening scene the camera shoots Ahmad Zaki from a distance, a deliberate strategy to draw the audience, especially elders, into accepting an actor—and such a well-known face—as Nasser. Other characters are played by less familiar, younger actors, closer in age to their characters, also a deliberate move to keep the film from becoming a parade of stars.[2] Documentary footage of world leaders and combat punctuate this and provide broader context for the story line. The only world leaders to appear in the scenario are Nehru and Australian Prime Minister Menzies, played by opera star and character actor Hassan Kami, Egypt’s master of foreign accents.[3] The black-and-white film also touches directly on a national bias for the classics, a nostalgia for black and white, from the era before color became the norm in the early seventies.[4]

Historical accuracy aside—and the debate was quickly engaged on levels great and small—the film’s success rests ultimately on popular reaction to the characterization of Nasser. Ahmad Zaki has by all accounts, and with only a minimum of makeup to fill out his jaws and recede his hairline, turned in a bravura performance that captures Nasser’s personality, demeanor, speech patterns, and, ultimately, charisma. This is important, because for the generations born after Nasser’s death in September 1970, Zaki will, for better or worse, come to personify his subject. The filmmakers, well aware of the burden on their shoulders, paid meticulous attention to detail, shooting on location whenever possible, attempting to re-create sets based on photographic evidence, and endeavoring to balance conflicting memories about the most prosaic specifics: the physical layout of the Nasser household or the brand of cigarettes Nasser chain-smoked.

The casting of Ahmad Zaki was both a foregone conclusion, because of his personal role in promoting the project, and a natural selection. Zaki has been Egypt’s premier dramatic actor since the late 1980s. Perhaps too often typecast in recent years as the poor boy trying to infiltrate the upper strata or as the social rebel, and recently reduced to plot-weak action films, he remains a powerful screen presence, a major box office draw, and occasionally a trendsetter.[5] He is also dark, rare for an Egyptian leading man (or woman), probably the darkest ever. He can, and easily does, approximate Nasser’s sa‘idi (Upper Egyptian) features. The rest is pure acting, and Zaki reportedly threw himself into the project and character, taking on Nasser’s persona on and off camera.

Fig. 2. A familiar guise: Ahmad Zaki as social rebel in ‘Atif al-Tayyib’s Didd al-hukuma (Against the Government, 1992). Photograph by Joel Gordon.

[Full Size]

Regardless of critical or popular reaction, the film will remain a milestone in Egyptian and Arab cinema history. It is the first film to dramatize the role of any contemporary Arab leader—with apologies to Youssef Chahine’s 1963 rewriting of the Crusades, al-Nasir Salah al-Din (Saladin the Victorious), which portrayed the Kurdish Saladin as a pan-Arab champion, clearly alluding to Nasser—and the first Egyptian film to treat such a significant historical period in anything but caricature. A handful of Egyptian feature films in the mid- to late 1950s dramatized the Suez conflict, some as backdrop, several directly. War stories, focused on steadfast soldiers and civilians, they depicted the struggle against traitors at home—a frequent invective in early Nasserist rhetoric—as well as imperialism (Ramzi 1984).[6]Nasser 56 decidedly has a point of view. It is a nationalist film—one Egyptian writer has called it a “quiet nationalism” (Ken Cuno, pers. com. April 1997)—but not a propaganda film in the classic sense. The target is no longer imperialism and Egyptian traitors but rather a present that has become detached from the moving spirit of a bygone era. If not a clarion call to restore that spirit, Nasser 56 is certainly a lens through which to reimage and reassess that which has been lost.