The Copy of the Grandes Chroniques

Presented to Philip III:

A Mirror of Princes

The earliest surviving Grandes Chroniques (Ste.-Gen. 782) is a luxurious manuscript commissioned around 1274 by the monks of Saint-Denis for presentation to Philip III, who had succeeded his father, Louis IX, in 1270.[20] It contained the newly translated vernacular version of the chronicles of Saint-Denis and 36 miniatures and historiated initials. Parisian artists who had undertaken commissions for Louis IX decorated the book.[21] Any analysis of its cycle of decorations must consider these circumstances of production.

Such an analysis must also consider the hierarchy of decoration, the scale and positioning of miniatures in relation to one another, and the relationships between text and illustration. Such an approach refines previous interpretations

and shows that the content of the pictures in this chronicle is closer in tone to contemporary Dionysian cycles than to royal cycles commissioned by Louis IX or Philip III.

The iconography of Philip III's Grandes Chroniques is particularly inventive. Although the pictures in this new text employ diverse models, they transformed them into a focused program. For instance, a compositional pattern for a battle scene employed as a shop model in the stained glass of Saint-Denis (for the capture of Nicaea by the crusaders) and of Chartres (for the capture of a Spanish city) was adapted to represent Philip Augustus's capture of Le Mans (fol. 295).[22] In this case, the adaptation does not seem to have influenced the content of the scene. Parisian artists who worked in varied media used this model to represent any number of battles.

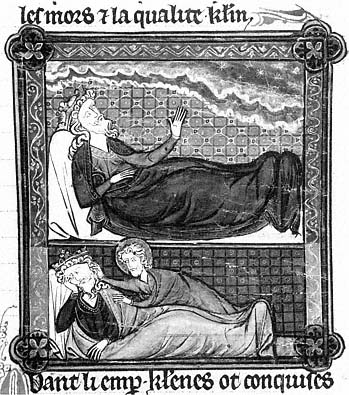

Some pictorial models may, however, have been more closely tied to their original texts. The clearest example of this is the Dream of Charlemagne (see Fig. 5), which illustrates a portion of the Grandes Chroniques translated from the chronicle of Pseudo-Turpin. The two scenes chosen for Philip III's manuscript are similar to those selected for such early monuments based on the text of the Pseudo-Turpin chronicle as the thirteenth-century châsse of Charlemagne at Aix-la-Chapelle. As in the Grandes Chroniques , this image combines the vision of the starry sky with the appearance of Saint James. The illustration of Saint James appearing to Charlemagne in the beginning of the Latin Pseudo-Turpin chronicle in the twelfth-century Codex Calixtinus and its fourteenth-century copies is also similar.[23] Although these earlier monuments form part of a rich visual tradition based on the Pseudo-Turpin chronicle—a tradition within which the image in Philip III's Grandes Chroniques belongs—the precise relationship between the illustration in the Grandes Chroniques and the earlier tradition is difficult to establish. Because the events represented in each image are described in both the Pseudo-Turpin chronicle and the Grandes Chroniques , the similarities between the châsse, Codex Calixtinus , and the Grandes Chroniques may be coincidental.[24] Artists may have arrived at their visual formulations independently.

The most sophisticated use of models in the Grandes Chroniques occurs in the adaptation of imagery from one text to illustrate another, as in the frontispiece of the chronicle. The first chapter of Book I of the Grandes Chroniques concentrates on tracing the genealogy of the French from Francion, the mythical son of Hector whose descendants founded France, whereas the picture that illustrates it concentrates on the rape of Helen. The beginning of the genealogy, which describes how Priam, ruler of Troy, sent his son Paris to Greece to avenge a slight committed by the Greek king, provided an opportunity to insert the frontispiece: Paris's vengeance was the abduction of Helen. The text of the chronicle goes on to describe the siege and destruction of Troy by the outraged Greeks and to tell how the few survivors of the city scattered all over the world.[25]

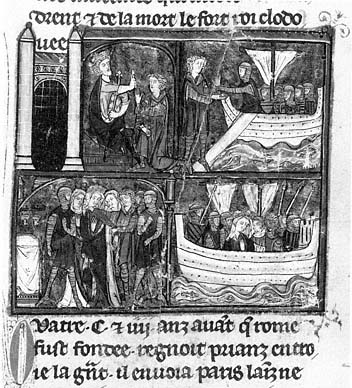

Only the first part of this brief Trojan account is illustrated in the frontispiece (Fig. 1). In four scenes the miniature portrays Priam dispatching Paris, Paris setting sail for Greece, Paris and his army capturing Helen in the temple of Venus, and the Trojans setting sail for Troy with their prize.

The picture offers more information than does its text because it was derived from another source, the Roman de Troie , written in the 1160s by Benoît de Sainte-

Figure 1

Priam dispatches Paris to Greece; Paris sets sail; Paris captures

Helen at the Temple of Venus; Paris and Helen set sail for Troy.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève,

Ms. 782, fol. 2v. Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris.

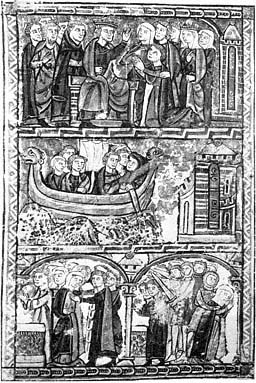

Maure.[26] The earliest surviving Roman de Troie (Fig. 2), a provincial manuscript dated 1264, near the time of the execution of the Grandes Chroniques , presents the closest analogies with the chronicle's frontispiece.[27] These miniatures share three of four scenes; they differ only in the last frame, where the chronicle's picture substitutes the departure of Paris, Helen, and the Trojan army for the Roman de Troie 's scene of the massacre in the temple that preceded the Trojan flight from Greece.

This major change and certain subtle alterations to the miniature of the rape of Helen minimize the unjust behavior of France's Trojan ancestors and thus make them more appropriate models for Philip III. The rape of a queen and the slaughter of innocent, albeit pagan, worshippers were not exemplary modes of behavior. However, these scenes were often paired and graphically illustrated in early cycles of the Roman de Troie and in their adaptation in the Histoire ancienne .[28] By contrast, the rape in the Grandes Chroniques could almost be a wedding; the

Figure 2

Priam dispatches Paris to Greece; Paris sets

sail; Paris captures Helen at the Temple of

Venus; Massacre of Greeks. Roman de Troie .

s'Heerenberg, Stichting Huis Bergh.

figures stand before an abbreviated altar in the presence of handmaidens and soldiers. The only suggestion of coercion in the image is Paris's firm grasp on Helen's wrist. Similarly, although it might be argued that the departure from Greece was added to round out the story, the scene was also appealing because of its nonviolent content. Both the text of the Grandes Chroniques and many later frontispieces go beyond the departure from Greece to offer a graphic depiction of the Greeks' revenge on Troy.

Despite their diverse origins, the illustrations of the first Grandes Chroniques form a carefully constructed program, one so particular to its time and place that the images had little influence on subsequent pictorial cycles. This Grandes Chroniques was produced for a specific audience; its miniatures reflect the historical preoccupations of the abbey of Saint-Denis, where it was commissioned, and provide certain models of kingship for Philip III, to whom it was presented.

Like the illustrations, two textual elements of this Grandes Chroniques support its special purposes. The French poem and prologue bracketing Philip III's book

present the Grandes Chroniques as a collection of exempla that follow the sequence of the three great French ruling houses in an effort to educate the young king Philip to be a good ruler. According to the prologue, the chronicle is to be a "mirror of life" in which "each person can find good and evil, beauty and ugliness, sense and folly, and profit in everything through the example of history."[29]

And because there have been three generations of kings in France since it all began, this history will be divided into three principal books: where the first will speak of the generation of Meroveus, the second of the generation of Pepin, and the third of the generation of Hugh Capet. Each of these books will be subdivided into diverse books, according to the lives and deeds of diverse kings; ordered by chapters to understand the material more easily and without confusion. The beginning of this history will be taken at the noble line of the Trojans from whom it [the French line] is descended by long succession.[30]

At the end of Philip III's Grandes Chroniques a special French poetic colophon, rarely copied in later manuscripts, addresses Philip directly.[31] Developing one theme sounded in the prologue—that of learning from the deeds of prior kings—it informs Philip that the manuscript was made for him to study and read in the hope that he would be a wise king. According to the poem, Philip should emulate the deeds of the good kings recorded in the chronicle and shun the example of the bad.

In their focus on the education of a young ruler these passages tie the chronicle to a newly forming tradition, the Mirror of Princes, a genre of political literature that remained popular throughout the Middle Ages.[32] Although Mirrors of Princes took varied forms, ranging from poetry to scholastic prose, they shared a royal audience and a content designed to teach a prince to govern with sound moral principles. The Capetian court of Louis IX, which probably provided the impetus for the translation of the Grandes Chroniques , played an important role in generating and consuming this type of political literature.[33] Indeed, the prologue and poetic colophon establish a reading of the chronicle that is consistent with our knowledge of Louis IX's use of history; Joinville, one of Louis's biographers, describes how the king told his children stories of past rulers to give them examples to follow and avoid.[34]

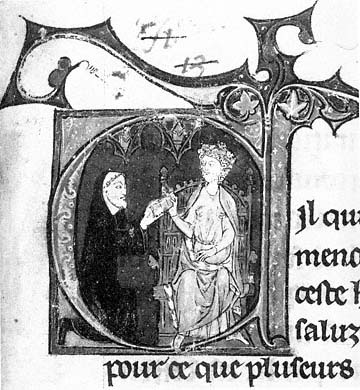

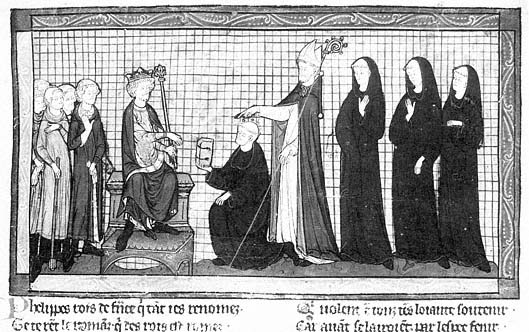

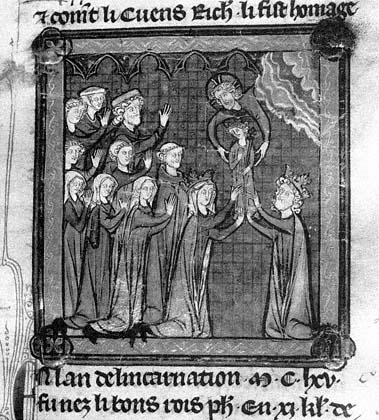

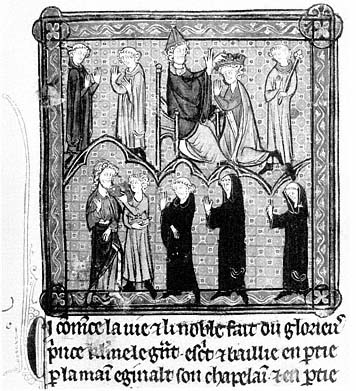

The miniatures of presentation that illustrate the prologue and poetic colophon frame the cycle of pictures in this manuscript and work with their texts to establish how the book should be read. In the first picture (Fig. 3), a kneeling monk humbly presents the chronicle to the king. The second picture (Fig. 4), the largest in the manuscript, transforms the presentation that inaugurates the chronicle, just as the poetic colophon elaborates themes presented in the prologue. In this two-column miniature the king is still enthroned and in his regalia, and Primat still presents his book, but Matthew of Vendôme rather than the king dominates the scene. Supervising the presentation, the imposing abbot stands so tall that the king must look up at him, and he and his monks occupy two-thirds of the picture's space. This miniature calls attention to the giving of the gift rather than its reception, and it suggests that the voice in the poem below it is Matthew's.[35] In doing so it celebrates the abbot's role in guiding Philip III and the important historiographic work done by Matthew of Vendôme and his monks.

Figure 3

Presentation of book to Philip III. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782, fol. 1.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris.

The distribution of miniatures in the chronicle proper does not follow the simple pattern established by the textual divisions. Primat's translation of the Latin chronicle is laid out as a series of books, all but one of them (the life of Louis VII) preceded by chapter lists: five books tell of the Merovingians and of Pepin (the first Carolingian); five books recount the exploits of Charlemagne; two describe Charlemagne's first two descendants—Louis the Pious and Charles the Bald; one records the lives of the later Carolingians and of the Capetians up until Louis VI; one each is dedicated to Louis VI and Louis VII; and three report the deeds of Philip Augustus.[36]

The miniatures in Philip III's manuscript are of two types. Larger, columnwide miniatures mark the beginnings of books describing the lives of the Merovingian rulers, the imperial Carolingians (Charlemagne, Louis the Pious, and Charles the Bald), and Philip Augustus. Smaller historiated initials decorate books and chapters that Matthew of Vendôme must have perceived as less important to Philip III—those that record the lives of the last Carolingians and all Capetian rulers except Philip Augustus. Illustrations break this basic pattern in three places: small historiated initials pick out two chapters at the end of the last

Figure 4

Presentation of book to Philip III. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève,

Ms. 782, fol. 326v. Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris.

Merovingian book, subdivide chapters in the lives of the last Carolingians, and mark the beginning of the chapter list in the life of Philip Augustus.

All these illustrations emphasize certain themes from the prologue of the Grandes Chroniques . Some, like the Trojan frontispiece and representations of good kingship in the lives of Charlemagne and Philip Augustus, are appropriate for the "Mirror" theme mentioned in the poem and prologue. Others relate more closely to the dynastic frame, the succession of races, also described in the prologue. Still others intertwine the histories of France and the abbey of Saint-Denis. As will become clear, all these themes are interdependent, so that the pictures weave together the textual themes of good kingship, dynastic continuity, and historical identity between France and Saint-Denis.

Models of Kingship

The Trojan frontispiece and the subcycles of the lives of Charlemagne and Philip Augustus shed light on the ideals of kingship promoted in the Grandes Chroniques given to Philip III. A comparison of the frontispiece with its probable model and of the illustrations of the lives of Charlemagne and Philip Augustus with the subsequent tradition helps to pinpoint consistent aims in the cycle.

As discussed earlier, the frontispiece of the first copy of the Grandes Chroniques emphasizes the Trojan ancestry of the French kings. With certain care-

ful modifications, it copies the most modern visual source for the story to show the ancestors of the French kings as suitable models for kingship.

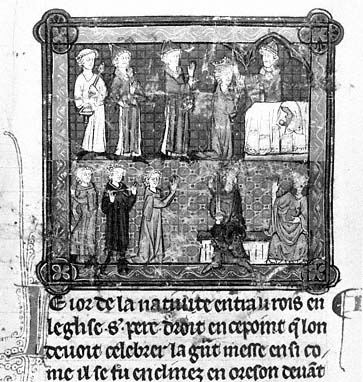

Pictures illustrating the life of Charlemagne provide similar models. Except for its opening miniature, the subcycle of the life of Charlemagne resembles early cycles of his life based on the Pseudo-Turpin chronicle and is typical of later cycles in the Grandes Chroniques .[37] Nonetheless, the repetition of the figure of Charlemagne in scenes from his life attracts the reader's attention. Thus the dream of Charlemagne encompasses two scenes (Fig. 5): in one the king first sees the vision of the starry road, and in the other Saint James appears to explain it to him. In the miniature of Charlemagne's coronation (Fig. 6) two images invert the relationships between the emperor and the pope. In the upper scene the church is supreme, and Charlemagne kneels to be crowned emperor in Rome at the hands of the pope; in the lower scene the state takes priority, and the pope pleads with Charlemagne to commute the sentences of those condemned by the emperor for degrading the pontiff.

Although these scenes derive directly from the chronicle's text, they depart from it in one important visual detail—they emphasize Charlemagne's kingship

Figure 5

Charlemagne has vision of the starry sky; Saint James

appears to sleeping Charlemagne. Grandes Chroniques

de France . Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782, fol.

141. Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris.

rather than his imperial status. Only the miniature of Charlemagne's coronation as emperor includes an imperial crown.[38] Its absence in subsequent miniatures is curious yet may be explained by the historical relationship of the French kings to the empire.

These pictures express a nationalistic tradition that held that Charlemagne was an important model of French kingship.[39] Until the twelfth century Charlemagne was viewed as ancestor of the West Frankish, or French, kings, but not as progenitor of the German rulers who became associated with the Holy Roman Empire.[40] With the exception of the German emperor, Frederick Barbarossa, who sponsored the canonization of Charlemagne in 1165, few Germans felt a popular sentiment for Charlemagne. In France, on the other hand, Charlemagne was immensely popular in both Dionysian and royal circles. As early as the twelfth century, the abbey of Saint-Denis employed numerous devices to tie itself to the growing cult of Charlemagne.[41] A forged charter suggested that Charlemagne had paid homage for France at the abbey. The monks mounted a campaign to promote the oriflamme , guarded at Saint-Denis, as Charlemagne's personal standard. This propaganda was effective and spread into vernacular chansons de geste , like the

Figure 6

Pope Leo III crowns Charlemagne at Rome; Pope and emperor

judge conspirators. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782, fol. 121v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris.

Pilgrimage of Charlemagne , which celebrated Charlemagne's fictitious trip to the East from which he brought back relics allegedly given later to Saint-Denis by Charles the Bald.

By the reign of Philip Augustus a cult of Charlemagne flourished in France, focusing on Charlemagne as emperor. It was employed primarily to justify territorial expansion.[42] In the popular imagination, reflected in chansons de geste of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Charlemagne's empire was equated with the kingdom of France: 170 passages in the chanson de Roland make this equation.[43]

In the late thirteenth century, when this manuscript of the Grandes Chroniques was produced, the association of France with the empire and the French king with the emperor seems to have had a different use. Despite, or perhaps because of, a botched attempt to secure the imperial crown, Philip III placed more emphasis on defining the limits of French kingship than on claiming the empire.[44] Political texts produced during his reign consistently underscore the French king's sovereignty—he is princeps in regno suo who "takes his power from no one except God and himself" (le roy ne tient de nului fors de dieu et de lui )—without any reference to the empire.[45]

The identification of the French king with Charlemagne in a ceremony described in the Grandes Chroniques further strengthened French kingship. Philip was the first king to use Charlemagne's sword, Joyeuse , in the ceremony of coronation, thus emphasizing Charlemagne's role as ancestor of the French kings.[46] Certainly, the portrayal of Charlemagne as a French king in the illustrations of Philip III's Grandes Chroniques was deliberate and, moreover, compatible with his consistent political posture.

Illustrations of the life of Philip Augustus are equally important in this manuscript, both as models of kingship for Philip Augustus's namesake and possibly as a further means of associating Philip III with Charlemagne. The hierarchy of decoration in the manuscript, as well as one particularly powerful miniature, mark this segment of the text with a special subcycle.

A historiated initial of the king enthroned begins the chapter list, and three miniatures illustrate the life of Philip Augustus. Only Philip Augustus's life has a historiated initial mark the chapter list, and miniatures rather than historiated initials illustrate the account of his reign—the first in the manuscript since the histories of the early Carolingians. Doubtless Philip Augustus alone of the Capetians receives such attention in part because he held a special place in the thoughts of Philip III. Philip Augustus was presented along with Saint Louis as a model for Philip III, as, for instance, in the dedication verses to Guillaume de Nangis's Life of Saint Louis .[47] Other writings from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries describe Philip Augustus as one of the first of a series of holy kings to rule France.

The first miniature of Philip Augustus's life (Fig. 7) suggests this king's holiness and miraculous birth: Christ swoops down from behind a cloud to present a young crowned king to Louis VII and his wife, who kneel in prayer with representatives of a cross section of society. This image is more emblematic than narrative. Instead of illustrating Louis VII's Christological vision (Philip Augustus giving the barons blood to drink from a chalice) or the actual birth of an heir—images that became canonical illustrations for this text in later copies of the Grandes Chroniques —this miniature focuses on Philip's sobriquet, Dieudonné . The picture derives from the text of the chronicle but combines Louis VII's prayer with its

Figure 7

Louis VII and Queen Alix receive Philip Augustus from Christ.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève,

Ms. 782, fol. 280. Photograph by the author.

response. The text describes how the king, his queen, and all the clergy and people of the realm prayed for the birth of a son. God heard their prayers and gave them Philip, a son whom Louis "nourished healthily and introduced plainly in the faith of Christ and the commandments of the holy church" and whom he had crowned at Reims when he was "of appropriate age."[48]

The portrayal of Philip as a crowned child holding a scepter contradicts part of the narrative; he was not crowned until he was 14 years old. Indeed, Philip's dress alludes to Louis VII's prayer, also recorded in the chapter, in which Louis requests an heir to rule: "Lord, give me a son, heir of my body, noble governor of the realm of France."[49] This boy clad in the attributes of kingship comes in answer to the prayer of the king and the populace for a "governor." The picture thus celebrates both the birth of Philip Augustus and the God-given kingship of France.

In this manuscript Philip Augustus and Charlemagne not only provide Philip III with distinct models for French kingship, but are also associated with

each other. This connection is emphasized by the layout of the cycle of decoration. A reader coming upon the group of miniatures illustrating the life of Philip Augustus might well recall that Charlemagne was the last ruler in this manuscript to have such a cycle.

Textual evidence provides further reasons for associating Philip Augustus with Charlemagne. The most famous text to do so is the reditus regni ad stirpem Karoli Magni , the prophecy that seven generations after the usurpation of the French throne by Hugh Capet, France would be returned to a ruler of Carolingian descent.[50] In this copy of the Grandes Chroniques , discussion of the reditus is limited to a small paragraph at the beginning of Hugh Capet's life which states that Philip Augustus married Elizabeth of Hainaut expressly to recover the line of Charlemagne.[51] In later copies of the chronicle an expanded discussion of the reditus appears at the beginning of the life of Philip Augustus's son, Louis VIII, who fulfilled the prophecy because he was descended from the Carolingians on both his mother's and father's sides.[52] Perhaps because Louis's life was not included in Philip III's manuscript, Philip Augustus is presented as the prime agent of the reditus .

The reditus affected Primat's translation of his sources. In describing the second coronation of Philip Augustus, which took place in Saint-Denis in 1180 during his marriage to Elizabeth of Hainaut, Primat transformed his Latin source, a text by Rigord, by explicitly referring to Charlemagne. The Latin text described how Elizabeth's uncle, Philip of Flanders, carried a sword with honor before the king; Primat's version speaks of "Philip of Flanders, who on this day carried Joyeuse , the sword of the great king Charlemagne, before the king as is right and customary at coronations of kings."[53]

These visual and textual references to Charlemagne and Philip Augustus are provocative because they may echo Philip Augustus's identification with Charlemagne, voiced most explicitly in the reditus . Primat's interpolation, moreover, may have been an attempt to establish a precedent for Philip III's use of Charlemagne's sword in his coronation and to strengthen the identification between Philip III and his great Capetian ancestor Philip Augustus. Mention of the sword Joyeuse was probably intended to recall Charlemagne, Philip Augustus's illustrious predecessor, and to refer to Philip III, his namesake who also used Charlemagne's sword in the ceremony. Thus both text and pictures present Charlemagne and Philip Augustus to Philip III as dual models of kingship.

Dynastic Continuity

Other illustrations in Philip III's Grandes Chroniques develop the dynastic theme of the prologue. These merge, yet differentiate, the sequence of Merovingian, Carolingian, and Capetian rulers that stretches back to Troy, and in the process they celebrate the legitimacy of the Capetians and of Philip III.

Two historiated initials break the pattern of illustrations in the first portion of the manuscript to address the transfer of government from Merovingian to Carolingian. The first (Fig. 8) portrays the coronation of Chilperic II, in a chapter that begins with a rubric, "Ci commence li fait du noble prince Charles Martel," which directs attention away from Chilperic to the mayor of the palace, Charles Martel. The second initial (Fig. 9) celebrates the prowess of Pepin, Charles Martel's

Figure 8

Coronation of Chilperic II. Grandes Chroniques

de France . Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms.

782, fol. 100.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris.

Figure 9

Carloman and Pepin capture Laon from their brother

Grifon. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque

Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782, fol. 103.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris.

son and the progenitor of the Carolingian line, shown with his brother capturing the city of Laon. The text describes how, as a reward for his nobility in defending the French realm, Pepin was crowned king of France by the pope, who noted the weakness of the last Merovingian rulers, whom he was deposing, and the strength of Pepin as true governor of the realm.[54]

A second, less explicit break of decorative pattern comes in the book dedicated to the lives of the last Carolingian and early Capetian kings. In this section historiated initials subdivide several chapters outlined in the chapter list. The clusters these form again imply that a transition of dynasties is a reward for good government. A sequence of scenes in one chapter creates a precedent for Capetian rule. In the first cluster (Fig. 10) Normans invade France because the Carolingian king, Charles the Simple, is too young and too weak to govern. In desperation the barons turn to the mayor of the palace, Odo Capet, and crown him king (Fig. 11). Odo governs but remains loyal to young Charles. As soon as Odo dies and the realm reverts to Charles the Simple, the political situation degenerates. The Normans invade again, only to be driven from the realm by the duke of Burgundy (Fig. 12). A second cluster of historiated initials represents the chaos that preceded Hugh Capet's accession to the throne. A sequence of three historiated initials shows the coronation of Louis V, the last Carolingian king (Fig. 13); the conflict between Louis's uncle, Charles, and Hugh Capet's army, which broke out because Hugh would not accept Charles's succession (Fig. 13); and the resolution of the crisis—Hugh Capet, descendant of Odo and, like Odo, mayor of the palace,

Figure 10

Invasion of the Normans. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque

Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782, fol. 208v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-

Geneviève, Paris.

becomes king (Fig. 14). As the chronicle describes it, "because Hugh saw that all the heirs and the line of Charlemagne were destroyed and also since [the line] died out and since there was no one to contradict him, he had himself crowned in the city of Reims."[55] Hugh's life does not show his assumption of power but rather depicts him already crowned and exercising his kingly prerogatives, in this case pardoning the count of Flanders at the request of the duke of Normandy.

This handful of historiated initials promotes the idea that the French ruling house draws its legitimacy as much from just government as from blood. Such legitimacy can be confirmed by blood, as the reditus suggests, but it is not necessarily created by it.[56] This view seemed to be foremost at Saint-Denis from the 1260s to 1280s, for it shaped other commissions, including the large sculpted tomb program for the abbey church and the Latin guide to the tombs written by Guillaume de Nangis.[57] The combination of distinct lines unified by the reditus in the tombs and in the Latin Abbreviated Chronicle supports my interpretation of Philip III's program of decoration. All three—the tombs, the Latin chronicle, and the pictorial cycle of Philip III's Grandes Chroniques —trace the lines of office of the French king and note each spot where succession based on good government and succession based on blood diverge. But in each the careful documentation of genealogical discontinuity is secondary to the celebration of continuity of the long line of good governors. This continuity was confirmed by the reditus , which reunified legitimacy of blood with legitimacy of succession to office in the Capetian descendants of Philip Augustus.[58]

Figure 11

Coronation of Odo Capet. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque

Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782, fol. 208v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-

Geneviève, Paris.

Figure 12

Normans driven from France by the duke of Burgundy. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782, fol. 209. Photograph by the author.

Figure 13

Coronation of Louis V; Army of Charles of Lorraine puts to flight that of Hugh Capet. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782, fol. 219. Photograph by the author.

Figure 14

Hugh Capet pardons the count of Flanders.

Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782, fol.

219v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris.

The Royal House and the Abbey of Saint-Denis:

A Shared History

The impetus toward self-promotion characteristic of commissions sponsored by the abbey of Saint-Denis explains the presence of one rare miniature in this Grandes Chroniques . The illustration for the first book of the life of Charlemagne comprises two scenes (Fig. 15). In the lower register, Childeric III, the last Merovingian king, is deposed and forced to enter a monastery.[59] Above this scene Pope Stephen II crowns Pepin, the first Carolingian ruler. Perhaps in an attempt to feature the coronation at Saint-Denis in which the pope took part, the composition in this miniature inverts the narrative structure common to every other multitiered miniature, in which the story unfolds from left to right and from top to bottom. This is therefore a specially tailored image whose subject does not recur in any later cycles.[60]

Although dynastic interests account in part for the inclusion of the miniature of Pepin's coronation, the history of Saint-Denis may explain its prominence. Because the ceremony took place at Saint-Denis, it was as much a part of the history of the abbey that produced the text as it was of the king who received the manuscript.[61] The illustration of Pepin's coronation served as a reminder to the king of the intertwined history of the abbey and the French royal house.

Philip III's Grandes Chroniques is a carefully crafted text decorated by illustrations that clarify the chronicle's dynastic and Dionysian content. Primat's French

Figure 15

Pope Stephen II crowns Pepin; Childeric III deposed. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782,

fol. 107. Photograph: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris.

text is more than a translation from the Latin; Primat rearranged the structure of his Latin model to focus more attention on Charlemagne and Philip Augustus, and he appended a prologue and a poetic colophon that together shaped the text as a Mirror of Princes.

Pictures reinforce many of Primat's innovations. The historiated initial at the prologue and the large miniature at the end of the manuscript strengthen this interpretation of the text, and the density of the cycles and scale of illustration promote the importance of Charlemagne and Philip Augustus as royal models. In addition, miniatures betray the circumstances of the book's production, stressing the concerns with dynastic legitimacy, which were important to royalty, as well as the historical ties between the French crown and the abbey, which were so evident in Dionysian commissions. These observations may explain why this pictorial cycle spawned no progeny despite its presence in the royal library at the Louvre.[62] Because Philip's Grandes Chroniques was commissioned for a special audience at a particular time, its pictures tailor the reading of the text to suit the needs of both Philip III and the abbey of Saint-Denis.