The Five Substitutions

The five substitutions of this continuation comprise two texts dealing with homage, illustrated with three miniatures; a third text describing events that surrounded Philip of Valois's succession to the throne of France, illustrated with one miniature; a fourth text, a short prefatory paragraph to the life of Saint Louis, with a full-page frontispiece and author's portrait; and a frontispiece for the whole manuscript. Each of the substituted folios contains textual or visual material unique to Charles V's Grandes Chroniques . Seen together, they constitute a forceful reaffirmation of the legitimacy of the Valois line in response to English claims to the French throne, accomplished in part by the assertion of parallels between Saint Louis and his Valois descendants.

The type of homage owed to the French king by the English ruler for his duchies in France had long been an issue between France and England and was

of particular importance to the early Valois rulers.[3] The dispute was rooted in the Treaty of Paris, concluded between Louis IX and Henry III in 1259, which called upon the French king to cede certain lands to the English king in return for his liege homage. Criticized for having alienated important lands in the treaty in exchange for mere homage, Louis retorted, as Joinville notes, "It seems to me that that which I give Henry III, I use well because he was not my vassal, and because of this event he enters into my homage."[4] The English kings grudgingly renewed their homage at each change of reign: Edward I paid homage to Philip IV of France in 1286, and Edward II paid homage to Philip IV (1308) and Philip V (1320). In none of these cases, however, did the king pay liege homage because he did not swear the oath of fidelity.[5]

When Philip of Valois came to the throne in 1328 he, like his predecessors, summoned the English king to pay homage for his duchies in France.[6] Edward III arrived at Amiens in 1329 but, like his father and grandfather, pledged a less-binding, conditional homage that omitted the oath of fidelity to the French ruler. Twice in 1330 Edward was summoned to appear in France in order to confirm that the homage of 1329 had been liege and to swear the oath of fidelity. In 1331 Edward sent a letter to Philip stating that he should have performed liege homage in 1329; however, he did not make the trip to France and, in fact, never performed liege homage in person.

The issue of liege homage is the focus of two of the four sets of substituted leaves in Charles V's Grandes Chroniques . As Paulin Paris and others have noted, these insertions expand short discussions of homage in the lives of Saint Louis (chapter 84) and Philip of Valois (chapter 6) with three miniatures and the texts of two documents from the Trésor des chartes: the Treaty of Paris and the letter Edward III sent Philip in 1331.[7]

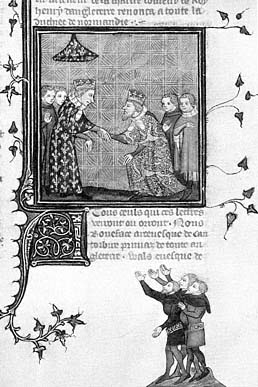

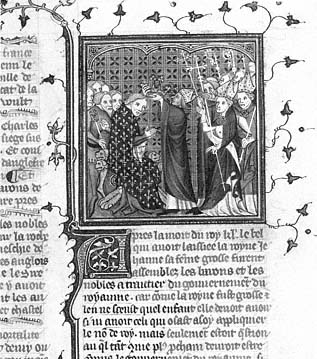

In the first miniature of homage (Fig. 81) Henry III kneels before Saint Louis and clasps his hands while witnesses peer from either side of the royal pair and from the lower margin of the page. Rather than occupying the traditional place at the head of the chapter, this miniature precedes the text of the Treaty of Paris, in which the English king first agreed to pay liege homage to the French king and his heirs for lands in France (Gascony, including Bordeaux and Bayonne, and the channel islands) and to renounce claims to lands held by the French in Normandy, Anjou, Touraine, Maine, and Poitou.[8]

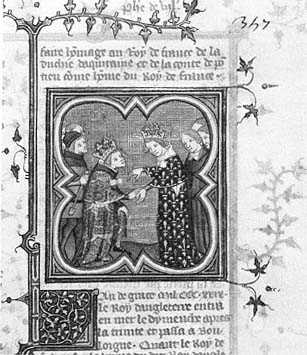

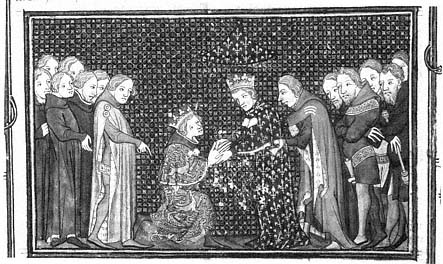

Two miniatures in the second insertion (Figs. 82 and 83) illustrate the letter sent to Philip of Valois in 1331, which not only confirmed that Edward should have performed liege homage in 1329, but also described the form that all future ceremonies of homage should adopt.[9]

The illustrated texts interpolated into the Grandes Chroniques at this stage of production blur distinctions between the homage that took place in 1329 and that which was described in 1331, distorting the actual ceremony of homage to bolster the French position and promote the legitimacy of the Valois line. Textual changes in the manuscript manipulate the description of the events of 1329 to imply that the English king unequivocally accepted the Valois succession immediately after Philip of Valois's accession in 1328, rather than three years later. In addition, the chapter describing the 1329 ceremony of homage incorporates the letter written in 1331, preceded by a paragraph stating that the plain homage paid in 1329 was just like the liege homage described in the letter. Raoulet writes, "Thus the English

Figure 81

Henry III's homage to Saint Louis. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Nationale,

Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 290.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

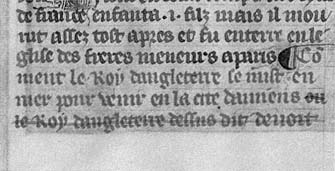

did homage to the king of France in the form and manner contained in the charter sealed with the seal of the king of England, whose content follows."[10] Moreover, to eliminate any shred of doubt, Raoulet further edits the rubric that he had placed at the beginning of the newly-inserted chapter (Fig. 84). The original rubric shows the English king as a less-than-willing participant: "How the king of England went to sea to go to the city of Amiens where the above-mentioned king had to pay homage to the king of France for the duchy of Aquitaine and for the county of Ponthieu as vassal of the king of France [my italics]."[11] Its corrected version, "How the king of England went to sea to go to the city of Amiens to pay homage to the king of France . . . ," suggests that the homage was freely offered.

The illustration that immediately follows this rubric freezes the English king's action as he prepares to kneel and extend his hands to clasp those of the French monarch. The next picture, at the bottom of the folio on which the letter begins, portrays a later moment of the ceremony, drawing its details directly from the description of homage in the letter. In this two-column miniature Edward kneels and places his hands, which are rendered in a scale larger than the rest of the image, within those of the French king. Aiding the French king is his chamberlain, dressed in a long, side-split mantle or hérigaut marked at the shoulder by three bands of white.

Figure 82

Edward III prepares for homage before Philip of Valois.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Nationale,

Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 357.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

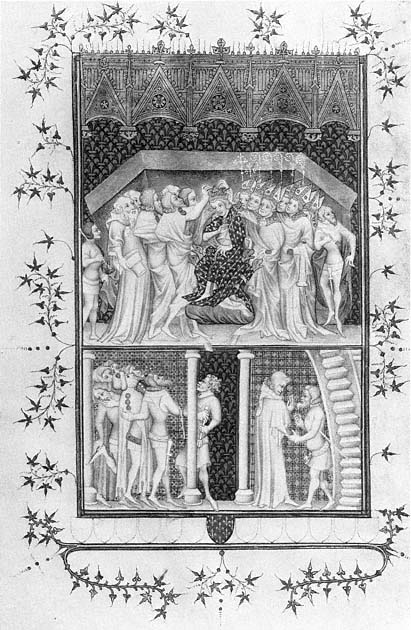

Figure 83

Edward III's homage before Philip of Valois. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 357v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

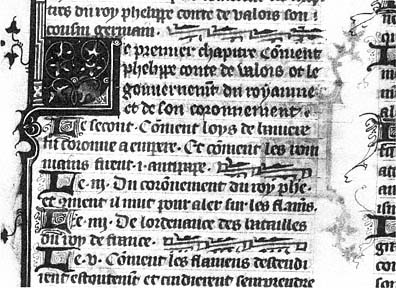

Figure 84

Edited rubric. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque

Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 357.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

The moment represented in the three illustrations reinforces the political content of their texts. The miniature of Henry III's homage and the two miniatures of Edward III's homage all focus on the gesture of immixtio manuum (handclasp)—significantly, the moment at which the vassal was most abject. This may have been the reason for illustrating it rather than another moment, such as the osculum (kiss). Also significant is the chamberlain's action in Edward's homage, for it marks the instant at which the English king swears the oath and thus submits to French authority. The presence of witnesses in all the miniatures verifies this act of submission.[12]

Additional visual details further stress the English king's submission to his French lord. In all three miniatures the English king wears a heavy gold crown, although the ceremony demands that the person swearing homage be bareheaded. This deviation was doubtless employed to identify both Henry III and Edward III. Indeed, contemporary illustrations of homage such as those decorating Charles's manuscript of the Homages du comtè de Clermont , known through an eighteenth-century copy made for Roger de Gaigniéres, often identify figures through details of dress.[13] In the depiction of the homage of Louis II of Bourbon from this manuscript, for instance, court personages are easily identified by their arms. Further, Louis is not bareheaded while offering homage but wears a thin circlet. Nonetheless, it is tempting to see the addition of crowns to the standard English arms as yet another way of emphasizing the king's submission.[14] The English monarch paid homage in 1259 and 1329 as duke of Gascony and Poitou, not as king of England. His representation in royal regalia presents the event as the homage of a king rather than a duke.

One of a series of contemporary letters documenting the negotiations between Philip of Valois and Edward III, added during the second continuation of Charles V's Grandes Chroniques , describes the ceremonies of plain and liege homage, clearly demonstrating that the only distinction between the two ceremonies was the wording of the oath.[15] The events represented in the added miniatures—the chamberlain's speech for the French king and the immixtio manuum —could therefore have been part of either ceremony. Yet the submission symbolized by the gesture of immixtio manuum seems to have been as important

an issue in the late fourteenth century as the propriety of liege or plain homage had been at the beginning of Philip of Valois's reign. Writers who favored the English side challenged Valois legitimacy by denying that the English king had performed this symbolic gesture, despite the fact that duplicates of the homage documents were available in England. Froissart, in a redaction of his chronicle, possibly identical to that presented in 1361 to the English queen, Philippa of Hainault, included this account of Edward III's homage before Philip of Valois: "The king Edward of England did homage by mouth [i.e., kiss] and words only, without putting his hands between the hands of the king of France."[16] A little later he asserted, "Many murmur in England that their lord was closer to the heritage of France than was king Philip."[17]

The textual source for Book I of Froissart's history—the chronicle of Jean le Bel—gives this account added significance,[18] for the description of homage is one of the few original passages that Froissart interpolated into Jean le Bel's text to produce the first redaction of his chronicle. Since this text was destined for the English queen, the interpolation of an original account questioning the legitimacy of the French ruling house doubtless reflects contemporary English political rhetoric and the importance of the immixtio manuum as a symbol of submission.

The inserted miniatures of homage thus function on three levels: they provide a clear illustration of the inserted documents; they underline the French view of the homage by emphasizing the gesture of submission and by identifying the participants through details of costume; and they illustrate Charles V's historic speech before his uncle, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, in 1378—a summary of which formed part of the continuation of the Grandes Chroniques written at the same time that the insertions were substituted into earlier portions of the manuscript.[19]

This speech, given before the royal council and the university community, outlined a litany of English provocations justifying the French resumption of war. Charles V opened his discourse with a description of the two incidents of homage, which are painted with extraordinary care and added to the manuscript. He then discussed the Treaty of Brétigny and the letter of confirmation that outlined the renunciations to which the English agreed. He further explained how, at each turn, the English had broken their word; they aided Charles of Navarre and condoned the Black Prince's atrocities in France. He emphasized that the French continued, despite these breaches of faith, to send messengers beseeching the English to rectify matters. Finally, Charles concluded, his nation had no alternative but to resume war with the English.

The summary of Charles's speech places great emphasis on proof of his assertions. References to documents shown to the emperor appear throughout. For example, the emperor was shown the "letters on this matter" (the letter of 1331 on homage); the "other, older charters" in which the "kings of England renounced lands" (Treaty of Paris); and the "treaty of the peace" (Treaty of Brétigny). Almost all these texts either already appeared in the Grandes Chroniques or were inserted into Charles V's personal copy during Raoulet's second continuation.

Charles V's speech had an impact on other portions of the manuscript as well. Marginal notes added by Raoulet d'Orléans single out almost all the other events cited by Charles V in his discourse and described earlier in the Grandes

Chroniques . Although notas are the most common form of annotation, detailed marginalia occasionally single out texts because of their relationship to the speech. One annotation even corrects a text (chapter 20) written during the second stage of execution, which states that the Black Prince imprisoned representatives of Charles V for a long time and "still holds them, in great contempt of the king and his sovereignty."[20] Next to this statement is a marginal note, underlined and framed by brown pen lines, which states, "Note: he had them killed."[21] This note updates the earlier continuation to conform with the version of the story given by Charles V in his speech when, in listing the excesses of the Black Prince, he said that the prince "had them taken and murdered evilly, against God and justice and in offense of the king and the realm of France."[22] This example is one of many that prove how carefully the director of the manuscript's layout underscored the relation between portions of text executed during the first and second stages of the manuscript and that portion written after the emperor's visit in 1378. The introduction of new texts containing specific images and the addition of complex marginal notes to texts already present in the manuscript draw attention to events and documents cited in Charles V's speech.

The third substitution of texts and images focuses exclusively on the problem of Valois legitimacy. In Charles V's Grandes Chroniques the first chapter of the life of Philip of Valois substitutes, as Paulin Paris and Jules Viard note, a description of Philip's uncontested accession to the throne for the traditional discussion outlining English and Navarrese claims.[23]

The care with which this alteration was accomplished is striking. Text, rubric, and illustration differ from their counterparts in all other Grandes Chroniques . The miniature of the coronation of Philip of Valois at the head of the first chapter initially appears to be a logical choice for the first illustration to a king's reign (Fig. 85) and, understandably, has not attracted attention. Yet almost every other manuscript of the Grandes Chroniques postdating Charles's copy provides a different image and rubric. Instead of the coronation, events such as a discussion between barons, a homage, or a battle are most commonly illustrated.[24]

A correction to the list of chapters dealing with Philip of Valois, which has been overlooked by compilers of critical editions of the Grandes Chroniques , suggests that the text surviving in later manuscripts, and most often illustrated by the baronial debate, may also have been the original in Charles V's copy. At the beginning of the chapter list on a folio written by Henri de Trévou (Fig. 86) an unknown rubric for chapter 1 was carefully scraped and the coronation rubric substituted by Raoulet d'Orléans. This new rubric ("How Philip, Count of Valois, received the government of the realm and of his coronation") may in fact have replaced the same rubric as that found in later manuscripts ("The first chapter addresses the question of to whom the government of the realm should be entrusted").[25]

Just as the changed rubric and text in Charles V's Grandes Chroniques gloss over the difficult transition from Capetian to Valois, the new miniature also portrays a smooth transfer of power. By illustrating Philip of Valois's coronation, this miniature underlines his continuity with those who had reigned before. Few modern readers looking at the revised account in Charles V's manuscript would suspect that Philip's accession contributed to the Hundred Years' War.

Figure 85

Coronation of Philip of Valois. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 353v

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Figure 86

Chapter list, life of Philip of Valois. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 352.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

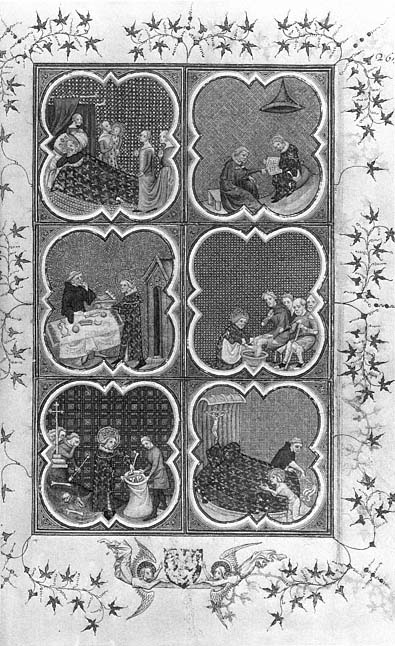

The fourth insert, the frontispiece to the life of Saint Louis (Fig. 87), contains six scenes: the nativity of Saint Louis, the education of Saint Louis, Saint Louis's care for the leper monk at Royaumont, Saint Louis washing the feet of the poor, the burial of the crusaders' bones at Sidon, and Saint Louis's submission to scourging by his confessor. These images reflect the Valois interest in the royal saint,[26] glorifying him as the ancestor of the Capetian and Valois lines and thus reinforcing the theme of dynastic legitimacy conveyed by the other inserted texts and illuminations.

Like Philip of Valois and John the Good, Charles promoted dynastic legitimacy by invoking his direct Valois ancestors and his saintly Capetian ancestor, Louis.[27] To stress continuity within the new dynasty, Charles decided to be crowned on Trinity Sunday, as his grandfather had been.[28] In another expression of dynastic pride, undertaken shortly after his coronation, he commissioned tombs for both his grandparents, Philip of Valois and his first wife, Jeanne of Burgundy; his father, John the Good; himself; and his queen, Jeanne of Bourbon, to make the first three Valois kings visible near their Capetian, Carolingian, and Merovingian ancestors in the royal necropolis at Saint-Denis.[29]

Even Charles's ordinance establishing the age of majority at 14 invoked Louis IX above other French kings. The text, whose publication in Parlement in 1375 was the subject of the last chapter of the second stage of execution of Charles V's Grandes Chroniques , cites Saint Louis among biblical and historical exempla of kings who assumed their majority at 14, even though historical evidence suggests that Louis IX was, in fact, 12 at the time.[30] A long passage in praise of Saint Louis as patron of France and as a model of good kingship follows.[31]

The inserted frontispiece to the life of Saint Louis constitutes a part of this pervasive Valois tradition. Like many Capetian commissions and like John the Good's Grandes Chroniques , its textual source is the Vie de Saint Louis by Guillaume de Saint-Pathus. Although most of its imagery derives from Saint-Pathus as well, certain deviations from established iconography are distinctive.[32]

The most innovative scene in the frontispiece, the nativity of Saint Louis, is the only miniature with no textual nor pictorial basis. Its inclusion establishes a relationship between the baby Louis and Charles V's infant son, later Charles VI, as he appears in the large two-column miniature of his baptismal procession from the chronicle's second stage of execution (Fig. 80). This comparison is relevant because Charles V and Jeanne of Bourbon had waited 18 years for the birth of their son. Their desire for an heir was strong enough to cause changes emphasizing fertility in the coronation ordo used in 1364.[33]

Almost every other Grandes Chroniques that illustrates Charles VI as a baby also includes a portrait of his younger brother,[34] nor does any other Grandes Chroniques picture Saint Louis as an infant. By omitting a picture of the birth or baptism of Charles's second son, Louis, in 1372 and including a picture of an infant whose presence is not even demanded by the text, this Grandes Chroniques establishes a connection between the dauphin Charles and Louis IX that underscores the expression of Capetian-Valois continuity in the insertions of homage and of the coronation of Philip of Valois.

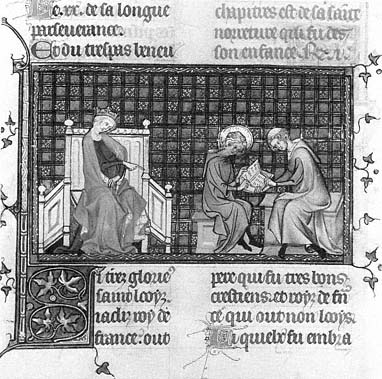

A second scene in the frontispiece is more concerned with Louis's kingship than with his place in Valois genealogy. An image of Blanche of Castille, enthroned and supervising the education of her son, normally illustrates copies

Figure 87

Frontispiece to the life of Saint Louis. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 265.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Figure 88

Blanche of Castile oversees Louis IX's education. Guillaume de

Saint-Pathus, Vie de Saint Louis . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms.

fr. 5716, fol. 16. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

of Saint-Pathus's Vie (Fig. 88), which supplied the model for the illustration of the education of Saint Louis in the Grandes Chroniques .[35] In the frontispiece the suppression of the queen and the changed relationship between teacher and pupil transform its tone. The authority of Louis's royal dress, his prominent position under a baldachin with his teacher on a low bench before him, and the absence of his mother shift the emphasis to Louis's kingship and away from the more conventional presentation of the instruction of a prince. This altered focus may reflect a changing ideal of kingship under Charles V, who earned his sobriquet, "the Wise," through his scholarly pursuits and who was often cited along with Saint Louis in discussions of the education of a French king.[36]

The fifth and final insert in Charles V's Grandes Chroniques is a miniature long thought to represent the coronation of Charles VI (Fig. 89). Scholars traditionally believed that this image was executed for the section of the manuscript that followed Charles V's life, then cut out and placed at the beginning when the two volumes of Charles V's manuscript were rebound as one in the fifteenth century.

The most persuasive argument against this interpretation is that Charles V's Grandes Chroniques ends abruptly in 1379, a full year before Charles's death and his

Figure 89

Peers support the crown. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque

Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 3v. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

son's accession: there could have been no text describing Charles VI's coronation. Moreover, there is no evidence that an account of the coronation was ever there. Over 50 blank pages are ruled at the end of the manuscript with no sign that anything has been cut out. The simplest explanation may therefore be that this coronation scene was inserted, along with the other pages, in the third stage of execution of the manuscript. Indeed, it may have been planned to serve as a full-page frontispiece to the first volume of the Grandes Chroniques , just as the inserted leaf with scenes from the life of Saint Louis acted as an extratextual frontispiece to the second volume of the chronicle.

The coronation miniature makes more sense in this context. It represents precisely the same moment chosen to introduce Charles V's life in his manuscript—the moment when the king is supported by the peers—but it serves a slightly different purpose here. In Charles V's life the image is packed with realistic details and heraldic charges, reflecting the specific problems with legitimacy and succession that Charles V faced in the 1370s. This frontispiece is more universal; it even includes spectators in the lower register. The fleur-de-lis drapery in the image of the monarch and in the background identifies the coronation as French, but no other figure in the scene is identified by heraldry. Instead, 12 blank shields are isolated on the ground in the lower margin, probably designed to receive the arms of the 12 peers who, according to tradition, assist in the ceremony. The image therefore celebrates France's sacred kingship and alludes to the peers' role, specified by Golein, in supporting and defending the king and the realm.