Dynastic Legitimacy and the Reditus

Charles V's concerns with the legitimacy of dynastic succession probably caused the suppression of the chapter on Hugh Capet when Charles's book was copied from Primat's presentation copy. The first portion of the suppressed text advances the doctrine of the reditus regni ad stirpem Karoli Magni . This was desirable material but could easily be omitted because the interpolated life of Louis VIII reiterates and expands upon the reditus theme. The second portion of Hugh Capet's life may have been the section that led to the chapter's suppression. In describing Hugh's reign, it includes an episode in which Hugh unjustly imprisons Arnoul, the archbishop of Reims, because Arnoul, though a bastard, is descended more directly than Hugh from the line of Charlemagne. As a result of his abuse of kingship, Hugh Capet is excommunicated. Only when Arnoul is freed and restored to his post is the ban lifted. Hugh Capet's fear of an illegitimate descendant of Charlemagne and the implication that Hugh was not a legitimate ruler may have provided sufficient reason for suppressing the passage in Charles V's book; it was uncomfortably close to events surrounding the Valois succession to the Capetians, when English claimants believed that they were more closely related to Saint Louis than were the Valois kings of France.

Hugh's life could be skipped without disrupting narrative continuity, because the chapters that precede and follow it provide a smooth transition. Charles of Lorraine's life ends by noting that after Hugh Capet ensured the extinction of Charlemagne's line, he had himself crowned in the city of Reims, and the life of Hugh Capet's son Robert begins with the statement that after Hugh died, Robert became king. Revisions in the text of Charles's chronicle thus ensured that the Capetians succeeded the Carolingians with a minimum of controversy.

Notes to Henri de Trévou in Philip's book reinforce the idea that the textual editing deliberately minimized questions about Hugh's legitimacy as ruler. The note to Henri in the margin of Hugh Capet's life in Ste.-Gen. 782 is the only one to show equivocation on the part of the designer. It originally consisted of the word "hyst," meaning "miniature." But "hyst" is crossed out and replaced by the words "une vignette," meaning "historiated initial"—"une" placed to the right of "hyst" and "vignette" to the left, thus downgrading the illustration originally planned for the passage on Hugh Capet.[13] Ultimately the picture was downgraded even further when this note was erased (it is now visible only under ultraviolet light) and the life of Hugh Capet was omitted from Charles V's chronicle.

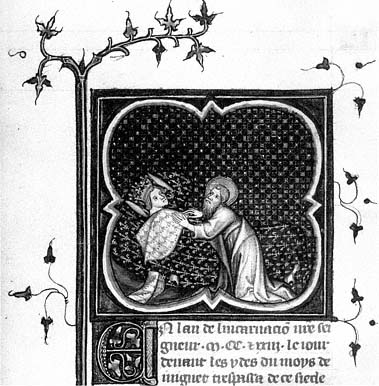

In Charles's Grandes Chroniques the illustration to the life of Louis VIII, the only other text to deal explicitly with the reditus and with dynastic change also minimizes the turbulence of the transition from Carolingian to Capetian government. Instead of featuring Louis's coronation or his actions in Aquitaine, as do virtually all earlier copies containing this text, this picture (Fig. 73) illustrates a prophecy that fixed a time for the reditus and provided a reason for the transition from Carolingian to Capetian government. According to this prophecy, Saint Valery rewarded Hugh the Great, the father of Hugh Capet, for translating his body and that of Saint Riquier. To thank Hugh the Great, Saint Valery appeared to him in a dream and revealed that Hugh's descendants would reign as kings of France for seven generations—precisely the amount of time between Hugh Capet and Philip Augustus, whose son Louis VIII fulfilled the reditus .[14]

By illustrating the Valerian prophecy, the miniature beginning Louis VIII's life leads the reader to skip over the preliminary materials of the chapter, which describe Hugh Capet's usurpation and the reditus , and to dwell on the miraculous promise to Hugh Capet's father, here shown as a king. As the Grandes Chroniques

Figure 73

Saint Valery appears to Hugh the Great. Grandes Chroniques

de France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 261.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

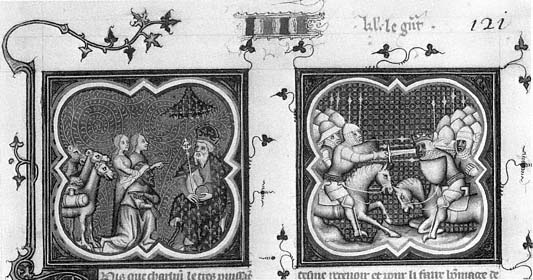

Figure 74

Charlemagne receives gifts; battle. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr.

2813, fol. 121. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

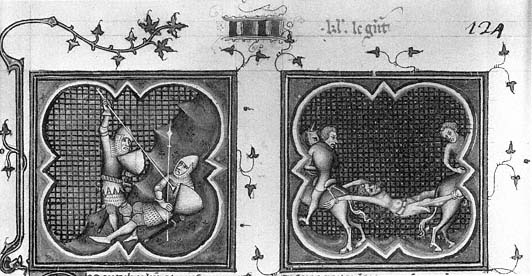

Figure 75

Combat determines Ganelon's guilt; punishment of Ganelon. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 124. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

states, Saint Valery's promise made it clear that the translation of the realm from Carolingian to Capetian was Hugh's reward for good works: his accession was a gift from God.