Chapter Five—

The First Stage of Execution (before 1375)

During the reigns of the first Valois kings, manuscripts of the Grandes Chroniques de France continued to offer different visual solutions to the problem of illustrating the chronicle. This situation changed when Charles V became king in 1364. Charles commissioned a continuation of the Grandes Chroniques that added accounts written at court about his father's and his own reign to the traditional history written by the monks at Saint-Denis about the Merovingians, Carolingians, and Capetians.[1] The copy of the Grandes Chroniques (B.N. fr. 2813) that this continuation expanded became an authoritative manuscript influencing a generation of royal and courtly books.

Charles V's manuscript incorporated the history of a new branch of the Capetians—the Valois—into the official history of the French kings at a time when the English crown was challenging the legitimacy of the Valois rulers. The addition of this new illustrated text to the king's copy of the Grandes Chroniques was a timely reaction to contemporary politics and a typical one for this bibliophile king.[2]

This version of the Grandes Chroniques took its present form in a series of four distinct campaigns of systematic modification and amendment[3] that enable us to trace the evolution of the complex interplay of words and images that characterizes Charles V's book. During the first stage of execution Henri de Trévou, the first scribe, wrote a two-volume chronicle that ended with the life of Philip of Valois. In the second stage of work Raoulet d'Orléans, the second scribe, introduced running titles, changed the last folios of the life of Philip of Valois, and added the narrative of the lives of John the Good and Charles V up to the events of 1375. During the third stage of production Raoulet d'Orléans recorded events from fall 1375 to spring 1379 and inserted five sets of text and miniatures into the first portion of the manuscript.[4] The fourth and final stage occurred in the fifteenth century when the manuscript was rebound into one volume.

Because it dates from three distinct moments in Charles V's reign (before 1375, before 1377, and after 1378), this manuscript offers a rare opportunity to reconstruct the genesis and expansion of a political program. During the second and third stages of production the editors of the manuscript altered the focus of the original decorative program to reflect current political concerns by adding new text and miniatures and, on rare occasions, by substituting new text and illustrations for those in the first section of the manuscript. Pictures added in these stages refer

to miniatures in earlier segments of text, either by adopting parallel formats or by using similar iconographical detail. These references provide secondary levels of interpretation to the text that become comprehensible when we analyze the three different versions of the manuscript as separate entities.

Miniatures decorating the first portion of Charles V's book are the least complicated in placement, format, and content. Usually positioned at the head of major divisions in the text, these images are, with few exceptions, one column wide. They depict coronations, battles, or court scenes in a generalized fashion. Perhaps because of their straightforward portrayal of events, these pictures have not been a subject of study.

Nevertheless, certain texts and illustrations in the first part of the manuscript are especially noteworthy. The hierarchy of decoration within the pictorial cycle; the relationship of Charles V's manuscript to its textual model, which also doubled as a maquette or dummy for the disposition of miniatures; and the divergences in the program of Charles V's Grandes Chroniques from that of a small group of manuscripts that closely copy it suggest that certain illustrated segments of the text were particularly important to the king. The lives of Charlemagne, Louis the Pious, Philip Augustus, and Saint Louis clearly have special significance, and the history of the early Norman dukes is detailed with a precision found in no other version of the Grandes Chroniques .

The format of certain miniatures presented as large double or four-part pictures distinguishes them as more important than other illuminations in the book. For example, the frontispiece to the manuscript (fol. 4) is a large image encompassing four scenes. The first pictures for the lives of Charlemagne (fol. 85v), Louis the Pious (fol. 128), Philip Augustus (fol. 223), and Saint Louis (fol. 266v) are all double miniatures. Double miniatures also illustrate two scenes from the story of Roland (fols. 124, 128).

Philip III's Grandes Chroniques (Ste.-Gen. 782), the model for a large portion of the text, provides further evidence for the significance of text, miniatures, and subcycles dealing with the dukes of Normandy, Charlemagne, and the concept of legitimacy. Kept in the royal library, this manuscript contains fourteenth-century marginal annotations addressed to Henri de Trévou, the scribe of Charles V's manuscript.[5] These dictate the placement or, in one case, the suppression of miniatures in Charles's chronicle and advocate the rearrangement of certain texts. Almost all these dictates were acted upon.

Two differences between Philip's Grandes Chroniques and Charles V's are unheralded by the marginal notes directed to Henri. These address the problem of legitimacy; they include the suppression of the chapter on Hugh Capet, the first of the Capetian line, and the introduction from another source of the life of Louis VIII, which had not yet been written when Primat completed his translation.

Four later books modeled on Charles V's Grandes Chroniques stress many of the same texts and include miniatures of the same subjects. Yet a comparison of these manuscripts suggests that certain innovations in the program of Charles V's book appealed to a narrow audience. For example, a manuscript of unknown provenance (Lyon, B.M. 880); two texts owned by Charles V's son, Charles VI (B.N. fr. 10135 and fr. 2608); and one owned by Charles VI's chamberlain, John of Montaigu, (Vienna, ÖNB 2564) neither omit Hugh Capet's life nor place great emphasis on the history of the Norman dukes. These features are unique to Charles

V's manuscript.[6] A comparison of these manuscripts also suggests that the dense cycle illustrating the life of Saint Louis may have had a special significance for certain kings of France since it appears only in Charles V's and Charles VI's copies.

Politics in the Duchy of Normandy

Charles V's interest in the history of the Norman dukes is not surprising in light of contemporary events. In the mid-1350s John the Good made Charles duke of Normandy.[7] In this capacity he had to contend with the attempts of his cousin, Charles of Navarre, to foment rebellion from his base in Evreux as part of an attempt to win the French throne. The situation was complicated by the activities of the English king, Edward III, a second claimant to the throne who periodically invaded Normandy. Charles V's attempts to gain control of Normandy were successful. With the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360 and Charles of Navarre's homage at Vernon in 1371, Charles V made tentative peace with his rivals. Nevertheless, as the French land closest to England, the duchy of Normandy remained a point of contention throughout Charles V's reign.

Charles's role as duke of Normandy may explain the pictorial emphasis on the lives of Norman dukes in his chronicle. By emphasizing a number of events in the history of the early dukes, rubrics and illustrations introduced into the book establish parallels between Charles's ducal predecessors and his royal ancestors. Some of the textual changes specified in the margins of Philip III's Grandes Chroniques highlight the activity of the early Norman rulers. First, they suggest the inclusion of new rubrics that increase the prominence of Dukes Rollo (Robert I) and Raoul of Normandy and Kings Louis, Lothar, Robert II, and Henry of France. In addition, they advocate the subdivision of certain chapters to stress divine intervention in the conquest of Normandy (the appearance of Saint Benedict to Count Sigillophes), emphasize the Christianity of the early dukes (the baptism of Rollo at which he took the name Robert), and discuss treachery against the Normans (the treason of the count of Flanders). They also note the Normans' ability to seek peace (alliance with King Lothar of France) and praise their repulsion of an English invasion (by Ethelred II) and their willingness to go on crusade. The only chapter formed by subdivision that deals with a French king discusses Robert II's generosity to the abbey of Saint-Denis just before his death.

The placement of miniatures, also noted in the margins of Philip's Grandes Chroniques , places equal emphasis on the importance of the Norman subcycle. For instance, the only annotation recommending suppression of an image occurs on folio 209 (Figs. 12 and 69), where a note to Henri suggests that he skip a miniature depicting Richard of Burgundy chasing the Normans out of his realm in order to insert a picture of the Normans landing in Neustria, two paragraphs later, at the commencement of the description of Rollo's activities. Three other miniatures illustrate chapters created by the subdivision of this portion of Primat's text.[8]

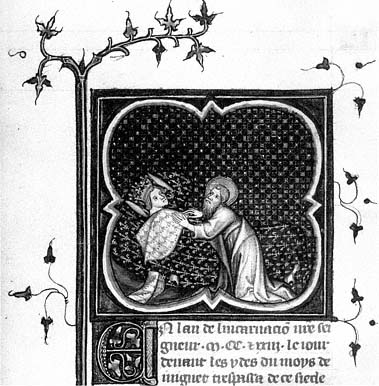

These newly subdivided chapters describe traits in the Norman predecessors of Charles V that were normally attributed to French kings. Chapters focusing on divine sponsorship, the repulsion of an English invasion, and the willingness to crusade illustrate kingly behavior. One chapter is subdivided to introduce a miniature celebrating the baptism of Rollo (Fig. 70), the first Christian duke of

Figure 69

Inscription addressed to Henri de

Trévou. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 782,

fol. 209. Photograph by the author.

Normandy. This event parallels the baptism of Clovis, the first Christian king of France. Clovis's baptism was especially important to the French kings because, according to legend, the holy unction that distinguished the French rulers from all others first appeared at Clovis's baptism.[9]

Saintly Ancestors as Models of Kingship

Charles V's political motives also explain the dense cycles of the lives of Charlemagne and Saint Louis, particularly since no visual models have been found for them. Charlemagne's importance for French kingship and his special significance to Charles V must have been a factor in the elaboration of this sequence of illustrations.[10] Charles had a chambre de Charlemagne in his Hôtel Saint-Pol and was often compared to Charlemagne in the prefaces of works that he commissioned, such as Raoul de Praelles's translation of the City of God in 1375.[11] Charles V was the first French king actively to promote the cult of Charlemagne. In a speech delivered in 1378 Charles even referred to "saint charlemaine," a status that Charlemagne was not usually accorded.[12]

As Charles V's only canonized ancestor, Saint Louis also earned a special place in the Grandes Chroniques . Devotion to Louis was widespread, particularly among his Capetian descendants, who commissioned numerous cycles of his life. Charles V's densely illustrated version of Saint Louis's life continues this Capetian tradition but may also assert the legitimacy of the new Valois line, as in John the Good's Grandes Chroniques .

Figure 70

The baptism of Rollo. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol.

166v. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

The French Kings and the Empire

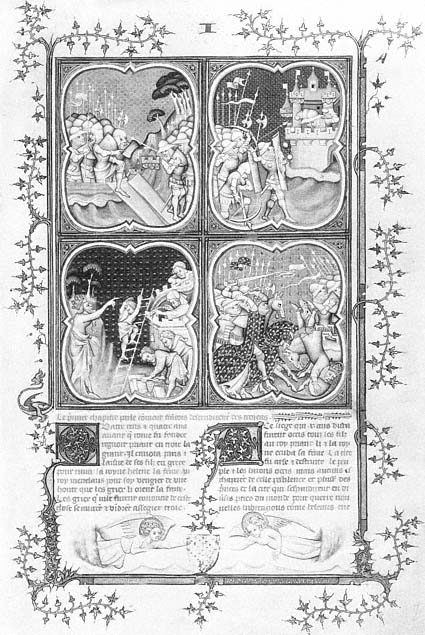

One image in the first version of Charles V's Grandes Chroniques , given special prominence by its format, may express the desire of the French kings to assert their independence of and equality with the Holy Roman Emperor. The four-part miniature (Fig. 71) preceding Book I illustrates the Greeks landing in Troy, their assault on the city, Francion founding Sicambria, and the defeat of the armies of Emperor Theodosius by Trojan descendants. The emperor's defeat is strongly emphasized. As the imperial army flees the Trojan onslaught, the emperor tumbles from his horse to land prominently in the foreground. The miniature clearly celebrates the Trojan ancestry of French kings: in the final, triumphal scene, for example, the Trojan king wears a tunic strewn with fleurs-de-lis, and his horse is richly draped in material of the same pattern. The triumph of the Trojans over the Roman emperor is therefore emblematic of the independence of France from the empire, as stressed in contemporary political theory.

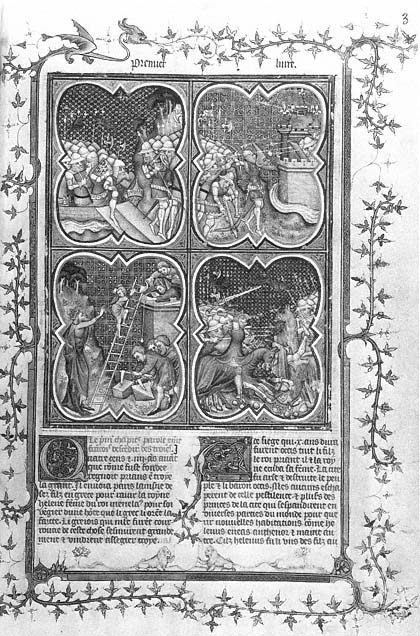

Such comparisons of royal and imperial status are restricted to royal manuscripts. The frontispiece to one of Charles VI's Grandes Chroniques (B.N. fr. 10135), which copies Charles V's manuscript (Fig. 72), is identical in composition

Figure 71

Greeks landing in Troy; Assault on a city; Francion founding Sicambria;

Trojans defeat imperial army. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque

Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 4. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Figure 72

Greeks landing in Troy; Assault on a city; Francion founding Sicambria;

Trojans defeat imperial army. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque

Nationale, Ms. fr. 10135, fol. 3. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

to this four-part miniature. It includes the image of the fallen emperor and signals the French presence by fleur-de-lis finials atop the towers of Troy. A third frontispiece from a contemporary, nonroyal Grandes Chroniques (B.N. fr. 17270, fol. 2v) also copies the four-part composition of Charles V's manuscript, but it suppresses the fleur-de-lis of France and the tumbling emperor. Although justified by the narrative, the careful equation of the Trojan and French kings and the inclusion of the fallen emperors in the two royal manuscripts elaborate upon their texts. The nonroyal manuscript omits any such elaboration, although the editor would have been familiar with the royal versions.

Dynastic Legitimacy and the Reditus

Charles V's concerns with the legitimacy of dynastic succession probably caused the suppression of the chapter on Hugh Capet when Charles's book was copied from Primat's presentation copy. The first portion of the suppressed text advances the doctrine of the reditus regni ad stirpem Karoli Magni . This was desirable material but could easily be omitted because the interpolated life of Louis VIII reiterates and expands upon the reditus theme. The second portion of Hugh Capet's life may have been the section that led to the chapter's suppression. In describing Hugh's reign, it includes an episode in which Hugh unjustly imprisons Arnoul, the archbishop of Reims, because Arnoul, though a bastard, is descended more directly than Hugh from the line of Charlemagne. As a result of his abuse of kingship, Hugh Capet is excommunicated. Only when Arnoul is freed and restored to his post is the ban lifted. Hugh Capet's fear of an illegitimate descendant of Charlemagne and the implication that Hugh was not a legitimate ruler may have provided sufficient reason for suppressing the passage in Charles V's book; it was uncomfortably close to events surrounding the Valois succession to the Capetians, when English claimants believed that they were more closely related to Saint Louis than were the Valois kings of France.

Hugh's life could be skipped without disrupting narrative continuity, because the chapters that precede and follow it provide a smooth transition. Charles of Lorraine's life ends by noting that after Hugh Capet ensured the extinction of Charlemagne's line, he had himself crowned in the city of Reims, and the life of Hugh Capet's son Robert begins with the statement that after Hugh died, Robert became king. Revisions in the text of Charles's chronicle thus ensured that the Capetians succeeded the Carolingians with a minimum of controversy.

Notes to Henri de Trévou in Philip's book reinforce the idea that the textual editing deliberately minimized questions about Hugh's legitimacy as ruler. The note to Henri in the margin of Hugh Capet's life in Ste.-Gen. 782 is the only one to show equivocation on the part of the designer. It originally consisted of the word "hyst," meaning "miniature." But "hyst" is crossed out and replaced by the words "une vignette," meaning "historiated initial"—"une" placed to the right of "hyst" and "vignette" to the left, thus downgrading the illustration originally planned for the passage on Hugh Capet.[13] Ultimately the picture was downgraded even further when this note was erased (it is now visible only under ultraviolet light) and the life of Hugh Capet was omitted from Charles V's chronicle.

In Charles's Grandes Chroniques the illustration to the life of Louis VIII, the only other text to deal explicitly with the reditus and with dynastic change also minimizes the turbulence of the transition from Carolingian to Capetian government. Instead of featuring Louis's coronation or his actions in Aquitaine, as do virtually all earlier copies containing this text, this picture (Fig. 73) illustrates a prophecy that fixed a time for the reditus and provided a reason for the transition from Carolingian to Capetian government. According to this prophecy, Saint Valery rewarded Hugh the Great, the father of Hugh Capet, for translating his body and that of Saint Riquier. To thank Hugh the Great, Saint Valery appeared to him in a dream and revealed that Hugh's descendants would reign as kings of France for seven generations—precisely the amount of time between Hugh Capet and Philip Augustus, whose son Louis VIII fulfilled the reditus .[14]

By illustrating the Valerian prophecy, the miniature beginning Louis VIII's life leads the reader to skip over the preliminary materials of the chapter, which describe Hugh Capet's usurpation and the reditus , and to dwell on the miraculous promise to Hugh Capet's father, here shown as a king. As the Grandes Chroniques

Figure 73

Saint Valery appears to Hugh the Great. Grandes Chroniques

de France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 261.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

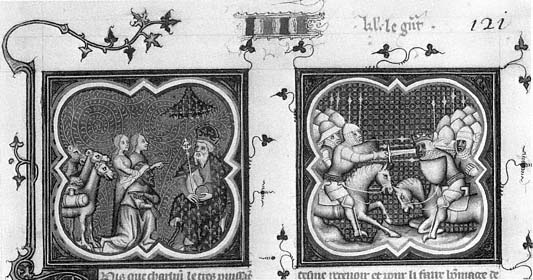

Figure 74

Charlemagne receives gifts; battle. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr.

2813, fol. 121. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

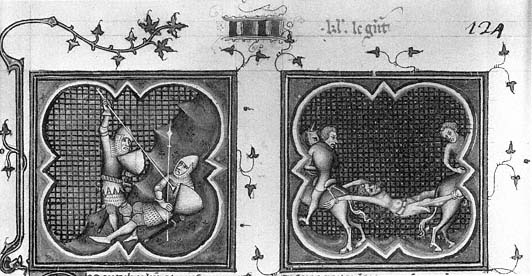

Figure 75

Combat determines Ganelon's guilt; punishment of Ganelon. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2813, fol. 124. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

states, Saint Valery's promise made it clear that the translation of the realm from Carolingian to Capetian was Hugh's reward for good works: his accession was a gift from God.

Kingly Behavior

The ideal of kingly behavior is the final theme featured in the program of Charles V's Grandes Chroniques at the end of the first stage of execution. This theme affected the rearrangement of chapters in the lives of the early dukes of Normandy, discussed earlier in this chapter. It also explains the inclusion of double miniatures in the story of Roland.

Two double miniatures from the life of Charlemagne represent a kingly prerogative: meting out justice in a just cause. Charlemagne's life was much more densely illuminated in Charles V's Grandes Chroniques than in its textual model; a cycle of nineteen miniatures replaces the five decorating the earlier book. Of the miniatures in Charles's codex, two in particular were laid out with special care. Twice in Book V of the life of Charlemagne (the story of Roland) a notation dictated that space should be left for a double miniature, a form of decoration that occurs only four times in over 380 folios and that in every other case heads the first chapter of a king's life.[15] These pictures illustrate a crime and its punishment. A double miniature (Fig. 74) represents the gifts sent as a false sign of peace to Charlemagne by Marsile, the Saracen king, with the help of Ganelon, one of Charlemagne's trusted advisors, and the subsequent battle in which Ganelon's treacherous act results in the slaughter of Charlemagne's men. The second pair of miniatures (Fig. 75) shows the just punishment for Ganelon's treason against a king. In one image the outcome of single combat determines Ganelon's guilt; in the second picture Ganelon is quartered by two horsemen.

The part of Charles V's manuscript written by Henri de Trévou is illustrated by generalized images, but these pictures nonetheless express ideas that become increasingly important in the formation of the program of illustration in subsequent continuations of this Grandes Chroniques . Through the rearrangement or suppression of texts and the importance accorded certain miniatures by their different formats, the first portion of the Grandes Chroniques focuses attention on Charles V's rights to Normandy, emphasizes the continuous descent of Capetian from Carolingian, and stresses the importance of saintly ancestors and just behavior. Finally, it highlights rulers of France who were also emperors and may assert the power of the French king vis-à-vis the emperor.