PART II—

DYNASTIC CHANGE AND THE REPRESENTATION OF HISTORY IN THE MID-FOURTEENTH CENTURY

Chapter Three—

Textual and Pictorial Innovation in John the Good's Grandes Chroniques

Because the last Capetians left no male heirs, the Capetian and Valois kings during the first half of the fourteenth century were plagued by the problem of royal succession.[1] When Louis X died in 1316, his wife was pregnant; his brother Philip, named regent for the duration of the pregnancy, became king when the newborn son died, because the treaty regulating the regency had laid the groundwork for the elimination of Louis's daughter from the succession. An assembly of barons confirmed Philip's selection in 1317. Philip V died without a male heir. He was succeeded by his younger brother Charles IV, who left a daughter and a pregnant queen at his death. Because of the precedent for female exclusion set in 1316, Isabelle, the sister of Louis X, Philip V, and Charles IV, was not considered for the succession after her youngest brother died. The barons instead chose Isabelle's cousin Philip of Valois as regent, and when Charles IV's widow gave birth to a daughter, they declared Philip king in 1328.

Two claimants to the French throne, Edward III of England and Charles of Navarre, objected to this exclusion of women; each claimed succession through his mother—Edward III through Isabelle, sister of the last three Capetian kings, and Charles of Navarre through Jeanne of Burgundy and Navarre, daughter of Louis X. The English claim, pressed from 1337, constitutes one of the primary causes of the Hundred Years' War. The younger pretender, Charles of Navarre, began to maneuver for the throne only during the 1350s.

Although the conflict between England and France escalated during the reign of Philip of Valois, most of the attacks were aimed at Philip's descendants, particularly John the Good, Philip's heir when the Hundred Years' War began.[2] Perhaps because of his shaky status, John actively commissioned manuscripts, particularly political texts. His Grandes Chroniques de France , one of the earliest of his manuscripts, is therefore best seen in its political context.[3]

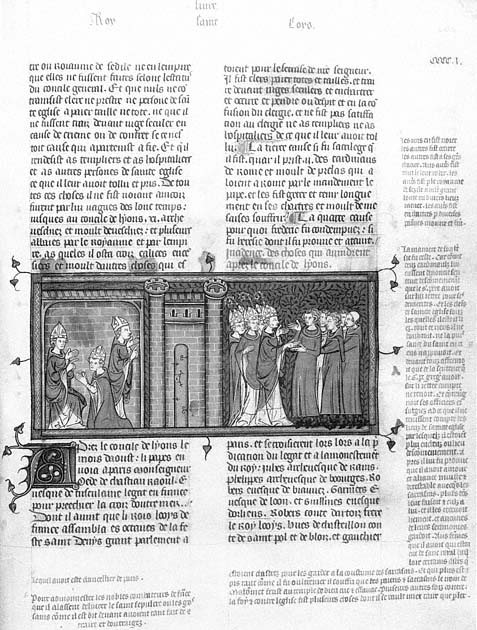

The copy of the Grandes Chroniques produced for John the Good (B.L. Royal 16 G VI) is one of the most luxurious French manuscripts of the fourteenth century. With over 400 illustrations incorporating more than 600 individual scenes, this manuscript contains a painstakingly revised text of the chronicle, which runs through the life of Saint Louis.[4] Although the book is not listed in any surviving inventories of the Louvre or in descriptions of John the Good's possessions

when he was captured at Poitiers in 1356, it belonged to John before he became king. On the first folio are John's arms as duke of Normandy, a title he held from 1332 to 1350. Moreover, at the end of the manuscript John's signature as duke has been erased.[5] A group of artists active for the court in the 1330s painted the book c. 1335–40.[6] Clearly, then, this Grandes Chroniques , now in London, was made for John when he was between 16 and 21 years old. Whether commissioned by John or by someone close to him at court, the manuscript offers a rare opportunity to examine the ideal of kingship deemed appropriate for the young heir to the throne. Further, the dense marginal annotations provide insights into the maturation of John's political thought.

Although the text in John the Good's chronicle is structured essentially like that of Philip III's, its content differs. Like Philip III's chronicle, John the Good's is divided into a sequence of books, each of which (with the exception of Louis VII's life) is introduced by a chapter list. John's manuscript, however, continues the Grandes Chroniques with lives of Louis VIII and Saint Louis, both without chapter lists.

The text in John's book was edited carefully by someone who went back to Primat's primary Latin source (B.N. lat. 5925) preserved in the library of Saint-Denis. Certain passages in the Latin manuscript were included without the corrections provided in Primat's French translation; other passages that Primat interpolated into his translation were omitted.[7] The compiler need not have been a monk of Saint-Denis, however, since he had access to such Parisian sources as the cartularies of Notre-Dame in Paris, which he used on at least one occasion to correct the Grandes Chroniques .[8] Further, his translation of Saint Louis's life consistently suppresses remarks relating to the Abbey of Saint-Denis.[9]

Most revisions in the body of John's Grandes Chroniques clarify the chronicle by specifying where events described in the text took place and by adding phrases like "près de Paris" to locate obscure places.[10] They also recommend further reading in the lives of saints for the history of the Merovingian rulers of France.[11]

John's Grandes Chroniques apparently retained its status as an important translation throughout his reign. Later in John's lifetime, the text of this manuscript was revised a second time.[12] The primary source for this revision was once again the Latin compilation (B.N. lat. 5925) preserved at Saint-Denis. Delisle showed that the editor prepared for his revision of John's Grandes Chroniques by annotating B.N. lat. 5925 with cross-references to a historical manuscript from Saint-Germaindes-Près (now B.N. lat. 12711), references to the chapter divisions of the French chronicle, and French glosses about faulty translations in the text of the Grandes Chroniques .[13] After verifying the translation in John the Good's manuscript, the editor annotated it extensively in French; his work was written in a clear Gothic bookhand in the margins (see, for example, Fig. 42).

Delisle correctly suggested that the revisions must have been made at court because the editor had easy access to manuscripts from Saint-Denis, Saint-Germain-des-Près, and the royal library. According to Delisle, the editor was Pierre d'Orgemont, the chancellor of John's son, King Charles V, who is thought to have supervised the continuation of the Grandes Chroniques in the 1370s during Charles's reign.[14] Delisle speculated that John's chronicle was annotated as a prelude to the production of Charles V's magnificent manuscript.

Textual evidence, however, supports a simpler theory—that John the Good ordered the revision. Both the tone of the annotations and their subject are consistent with the initial translation done for John. Like the body of John's Grandes Chroniques , the elaborate marginal annotations primarily retranslate Primat's Latin source. They thus share the concern for clarity and authenticity that informed John's manuscript in the 1330s and follow the same method of compilation. Moreover, Delisle's theory fails to explain why Pierre d'Orgemont would collate several manuscripts and annotate John the Good's chronicle in preparation for his work for Charles V only to turn to another textual model for the first portion of Charles's manuscript, Philip III's copy of the Grandes Chroniques (Ste.-Gen. 782), preserved in the royal library. Finally, the few cursive annotations in the margins of B.L. Royal 16 G VI do not support Pierre's authorship of the new translation. These notes were not written by the same hand (presumably Pierre d'Orgemont's) that covered the margins of the first Grandes Chroniques with cursive directions to the scribe of Charles V's manuscript.[15] The inescapable conclusion is that the editor of Charles V's book had little or nothing to do with the production of the chronicle preserved in the British Library.[16]

The relation between the marginal annotations and the pictures in John's chronicle suggests that the marginalia were designed to enhance John's manuscript, not to prepare for a more authoritative version of the chronicle. Two annotations comment on miniatures to clarify the text. The first corrects faulty heraldry in a miniature from the life of Louis VI (fol. 301), which should depict Henry I of England sleeping with his arms at the ready but shows the arms of France rather than England beside the recumbent king. A referencing mark, :/, like those used to insert annotations, appears in the margin closest to the arms in the miniature, and above it ":/ Angleterre" is written in cursive. A second marginal note in Gothic bookhand explains an ambiguous picture in the life of Philip Augustus (fol. 362v), showing a king, presumably John of England, paying homage to Philip Augustus. The accompanying text describes a visit of the English king to France and recounts an incident in which King John failed to comply with Philip Augustus's request to come to Paris as a peer. The picture does not illustrate either incident. Apparently this confusion was evident to the annotator of John the Good's manuscript: he added a marginal note later in the same chapter, beside a text describing how Philip gave Arthur, the nephew of John, the counties of Brittany, Anjou, and Poitou, along with 200 knights and a sum of money, explaining the illustration with a phrase drawn from the Latin life of Philip Augustus: "King Philip received him [Arthur] perpetually in liege homage."[17]

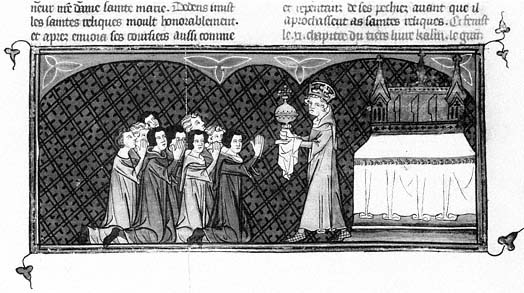

The iconography of Saint Denis also supports the Parisian provenance for the manuscript. Three scenes (fol. 183, Charlemagne prays at Saint-Denis; fol. 235v, Charles the Bald gives gifts to Saint-Denis; and fol. 302v, Louis VI prays at the abbey of Saint-Denis) include a distinctly Parisian representation of Saint Denis: Denis appears with all but the top of his head intact (Fig. 31). This image is in keeping with the assertion of the canons of Notre-Dame that they possessed the relic of the top of Saint Denis's cranium. First proposed during the reign of Philip Augustus, this claim was immediately contested by the monks of Saint-Denis and continued to be a subject of active debate into the fifteenth century when it came to trial before the Parlement of Paris.[18] If Royal 16 G VI were a gift to John from

Figure 31

Charles the Bald presents gifts to Saint-Denis. Grandes Chroniques de France .

British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 235v. By permission of the British Library.

the monks, as Ste.-Gen. 782 had been to Philip III, it is doubtful that such imagery would have been included.

If we reject Delisle's theory that Charles V's chancellor directed the revision of this Grandes Chroniques , then the London chronicle takes its rightful place as an important example of John's literary patronage. Following the lead of his mother, Jeanne of Burgundy, John the Good commissioned numerous translations of religious books and politically oriented texts, many of which were densely illustrated.[19] The Grandes Chroniques surviving in the British Library may well be one of the earliest of these commissions.

Pictures are integral parts of John's Grandes Chroniques . Almost every chapter has a miniature; 418 illustrations contain over 600 scenes. Curiously, this wealth of imagery has never been fully examined, despite its significant difference from all other royal copies of the chronicle. This neglect may be the result of John's image as a chevalier who loved the hunt, relished battle, and lived luxuriously,[20] a view that colored certain interpretations of his manuscript and led scholars to dismiss its pictures as derivative. Stiennon and Lejeune, for example, concluded that the

manuscript derived its cycle of Roland from chansons de geste[21] and that its pictures did not even illustrate the chronicle. Historians of art have therefore restricted their analyses of this book to studies of style.[22]

Yet the illustrative cycle of John's Grandes Chroniques is never purely derivative but creatively modifies its sources, as demonstrated in its relation to Philip III's chronicle (Ste.-Gen. 782), which, as the only other copy of the text known to have been in the royal library, may have been a source, and to a historical and hagiographic text also preserved in the royal library, the Vita et Passio Sancti Dionysii of Ivo of Saint-Denis.

If the compiler of John's Grandes Chroniques consulted Philip III's book, he adapted only certain aspects of its pictorial layout. For example, in both royal manuscripts the lives of the imperial Carolingians (Charlemagne, Louis the Pious, and Charles the Bald) are more densely illustrated than other royal lives. Philip's manuscript, however, places great emphasis on the imperial Carolingians, thus associating Philip Augustus with the early Carolingians—particularly with Charlemagne—as royal models for Philip III. John's Grandes Chroniques , on the other hand, does not involve the imperial Carolingians in a system of sophisticated pictorial cross-references but simply illustrates their texts and, through variations in scale and density, emphasizes themes already present in the chronicle. Most of the numerous illustrations to the lives of Charlemagne, Louis the Pious, and Charles the Bald in John's chronicle concentrate on themes that provide appropriate models for his kingship: Charlemagne's military prowess and his piety. The fact that John took part in battle from an early age might explain why the seven pictures (fols. 141v, 143, 144, 145v, 147, 148v, and 149v) illustrating Charlemagne's campaigns in the second book of his life are two columns wide. Charlemagne's piety is a less common theme for a prince's book; nonetheless, John's manuscript contains a pair of double miniatures followed by a series of seven scenes in which Charlemagne in Constantinople receives the relics of Christ's suffering (fols. 159, 160), brings the relics home (fol. 161v), witnesses their miraculous properties (fol. 162v), and displays them to the populace at the fair of Lendit (fol. 163). Indeed, Charlemagne's recovery and adoration of Christ's relics are given more emphasis than the crusade by which they were acquired. Such an unusual combination of military prowess and religious devotion was doubtless intended to demonstrate the desired balance between worship and action in a Christian king.

The admonitions added to the text to look for more information in the lives of the saints were taken to heart in its program of illustrations. The pictures of John's Grandes Chroniques blend images drawn from a variety of hagiographic traditions into an integrated cycle that closely illustrates its text. For example, one particularly dense subcycle in the Grandes Chroniques relates to an illustrated saint's life preserved in both the Dionysian and royal libraries: the Vita et Passio Sancti Dionysii by Ivo of Saint-Denis.[23]

Ivo of Saint-Denis's history, the third portion of the Vita et Passio , begins with the fall of Troy and ends in the reign of Philip V. Even though its structure, like that of the Grandes Chroniques , follows a sequence of royal biographies, its content focuses on the role in French history of Saint Denis and the abbey that bears his name. Predictably, one of the fullest royal cycles in Ivo's historical

compilation illustrates the life of Dagobert, the royal founder of the abbey of Saint-Denis.

Dagobert's life is also the most densely illuminated of the Merovingian kings in John's Grandes Chroniques ; five 2-column miniatures are among 14 pictures dedicated exclusively to Dagobert. The iconography and style of this cycle are closely related to those of a contemporary copy of Ivo's text (B.N. lat. 5286), the only surviving witness to the full cycle of illustration in Ivo's presentation copy and a reliable guide to its cycle of illustrations. The pictorial model of Ivo's history is, however, transformed in John's book in order to concentrate on French kingship.[24]

A comparison of images from the Grandes Chroniques with equivalent scenes from the Vita et Passio demonstrates how carefully the pictures in John's chronicle were selected. The Vita et Passio includes six full-page miniatures, read left to

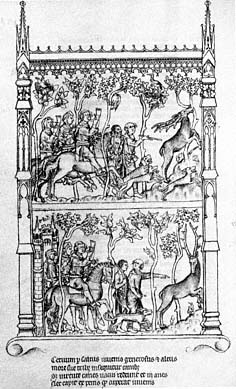

Figure 32

Sighting and pursuit of stag. Ivo of Saint-

Denis, Vita et Passio Sancti Dionysii .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. lat. 5286, fol.

135v. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

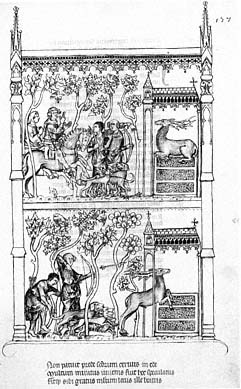

Figure 33

Stag takes refuge in Saint-Denis. Ivo of

Saint-Denis, Vita et Passio Sancti Dionysii .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. lat. 5286, fol. 137.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

right and bottom to top, that illustrate the discovery of the tomb of Saint Denis by Dagobert. The sighting and pursuit of the stag, complete with the hunters blowing horns in the first miniature (Fig. 32), is a separate image from the second, the stag's entry into the church containing the tomb of Saint Denis from which Dagobert and his fellow hunters were miraculously excluded (Fig. 33). Two subsequent miniatures show why Dagobert needed to seek refuge at the tomb. In the third, Dagobert's tutor insults him, and Dagobert humiliates his tutor as a punishment (Fig. 34). In the fourth, the tutor appeals to King Clotaire for revenge, Dagobert seeks sanctuary at the tomb from his father's wrath, and soldiers are sent to bring him back for punishment (Fig. 35). In the Dionysian manuscript of the Vita et Passio the king does not go to the tomb until his emissaries have failed to gain entry. The flurry of activity in this sequence of illustrations to Ivo's history centers on the tomb, which is also the central focus of the tale.

Figure 34

Dagobert tests and punishes his tutor.

Ivo of Saint-Denis, Vita et Passio Sancti

Dionysii . Bibliothèque Nationale,

Ms. lat. 5286, fol. 138v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Figure 35

The tutor demands revenge; Dagobert

seeks sanctuary at Saint-Denis. Ivo of

Saint-Denis, Vita et Passio Sancti Dionysii .

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. lat. 5286, fol.

139v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

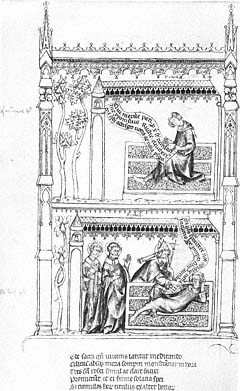

The story concludes when Saint Denis and his companions appear to Dagobert who, inspired by them, writes to his father (Fig. 36) and is reconciled to him (Fig. 37).

Although all the events pictured in Ivo's history are described by the text of the Grandes Chroniques , the miniatures in the chronicle are concerned less with the tomb than with Dagobert's miraculous protection by Saint Denis; extraneous details of the hunt are omitted. Dagobert's discovery of the tomb of Saint Denis and his companions is the focus of only two large miniatures in John's Grandes Chroniques . The first (Fig. 38) combines the chase after the stag with the frustration of the hunters when they cannot reach their quarry because Saint Denis protects it. The second image (Fig. 39) illustrates how Dagobert takes advantage of Saint Denis's protection after he has humiliated his tutor and

Figure 36

Saint Denis and companions appear to

Dagobert; Dagobert writes to his father.

Ivo of Saint-Denis, Vita et Passio Sancti

Dionysii . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms.

lat. 5286, fol. 140v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Figure 37

Dagobert reconciled with King Clotaire.

Ivo of Saint-Denis, Vita et Passio Sancti

Dionysii . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. lat.

5286, fol. 141v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

sought sanctuary from his father's wrath in the place where the stag has been protected.

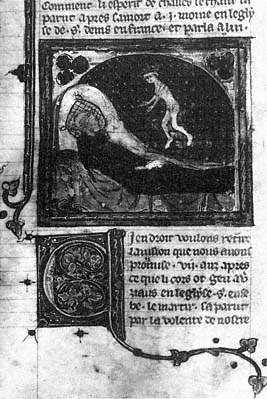

The pictures in the Grandes Chroniques also emphasize Dagobert's relationship with his father, the king. Unlike Ivo's Vita et Passio (Fig. 35), the Grandes Chroniques portrays King Clotaire accompanying the messenger (Fig. 39), even though a small minature illustrating Dagobert's vision and his reconciliation with Clotaire (Fig. 40) appears later in the correct narrative sequence. By stressing King Clotaire's exclusion from his son's refuge, John's chronicle shifts the focus away from Saint Denis's tomb—the center of attention in Ivo's Dionysian text—to the royal story, the relation between father and son.

As this small portion of the cycle of Dagobert's life demonstrates, the illustrative program of this Grandes Chroniques is independent of contemporary iconographical sources. The pictures of Dagobert's life are not simply quotations from preexisting, mainly Dionysian, cycles. They are free adaptations designed to focus attention on Dagobert. Indeed, the parallel scenes of Dagobert's hunt and sanctuary in the Grandes Chroniques are two of only five large scenes among the 14 minatures that illustrate his life. They are given large scale as an important early manifestation of Dagobert's special status, just as the last large miniature, in which Dagobert establishes his testament in conference (fol. 107), demonstrates the full fruition of his kingly wisdom as he provides for his succession.

Numerous other sources for the illustrations of John the Good's Grande Chroniques probably exist; Stiennon and Lejeune imply parallels with the

Figure 38

Hunt of the stag. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 92.

By permission of the British Library.

Figure 39

Dagobert in sanctuary. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 93v.

By permission of the British Library.

illustration of romances, although this has not yet been proven.[25] Despite its numerous sources, however, John's chronicle is a carefully constructed whole in which the densest cycle of pictures to appear in any manuscript of the Grandes Chroniques complements a thoroughly revised and glossed text. Derivative or not, the pictures were selected to work with their text in a program of decoration, and they are best understood in that context.

Interpretations that concentrate solely on visual or textual sources for the imagery of John the Good's book fail to account for either the internal structure of the manuscript or the close relationship between the text of the chronicle and its 418 minatures. The pictorial structure of the book is not tightly woven, but multiple miniatures introduce and subdivide chapters to stress certain distinctive themes,[26] suggesting that certain portions of the text had special importance for John the Good. The lives of Charlemagne, Louis the Pious, and Charles the Bald—the imperial Carolingians—contain an especially dense concentration of illustrations; 77 of 97 miniatures in this portion of the chronicle are two columns wide, as compared to 126 of 321 in the rest of the book. Occasional clusters of two-column miniatures also occur in the lives of Clovis, Dagobert, and Charles

Figure 40

Dagobert's vision and reconciliation with

Clotaire. Grandes Chroniques de France .

British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 94v.

By permission of the British Library.

Martel. Crusading imagery and the representation of relics are carefully detailed in pictures that may have been timely responses to contemporary politics. If there is one overarching theme in the cycle as a whole, however, it is the celebration of France's God-given kingship, whose holy character was confirmed by the sainthood of Louis IX.

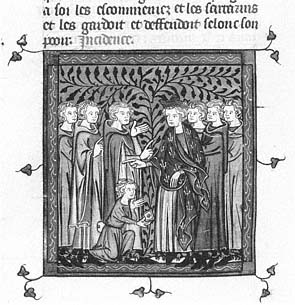

Politics and the Problem of Succession

The illustration to the prologue and the changes to its text establish the theme of succession as central to John the Good's Grandes Chroniques . The prologue's miniature (Plate 1) is a nonnarrative image showing the coronation of an enthroned pagan king of France flanked by a pagan duke and two Christian rulers. Their costumes identify them: the duke wears a circlet, and the kings wear crowns adorned with fleurons; checkered patterns mark the robes of pagan rulers, and the fleur-de-lis, given to the French during the reign of Clovis, the first Christian king, distinguishes Christian rulers.

The pagan duke stands on a pedestal to the left of the enthroned king, and the Christian kings stand on pedestals to the right. This arrangement suggests that they should be interpreted as the predecessor and successors of the king whose coronation is taking place. If this is the case, then the sequence of pagan duke to pagan king to Christian kings identifies the coronation as that of Pharamond, the first king of France.

To an audience familiar with the court, as readers of this royal manuscript would have been, this miniature must have recalled the sequence of sculpted kings, beginning with Pharamond, that decorated the Grande Salle of the royal palace. A change in the prologue reinforces the pictorial reference. Just after the description of the three lines of kings who governed France, John's chronicle modifies the phrase in the prologue, "The beginning of this history will be taken at the noble line of the Trojans from whom it [the French line] is descended by long succession," to read "is descended by succession of time."[27] Neither picture nor text places undue stress on the relationship of these rulers by blood. Both seem to celebrate instead the continuity of the office of king, to which the king is elected and in which he is supported by the barons who help place the crown on his head in the miniature.

These changes in image and text may have been timely responses to the difficulties created by the succession of the early Valois kings. In the late 1330s, when this Grandes Chroniques was produced, Edward III was the main threat to John the Good, claiming the French throne and waging campaigns against the French in propaganda and on the battlefield. Edward's claim, supported by his political and military maneuvers, helps to clarify the imagery of the introductory miniature and to reveal its relation to its text and perhaps to the rest of the cycle.

Edward's anti-Valois propaganda, which centered on John, the heir apparent, rather than his father, Philip, the first Valois king,[28] may well have begun before Edward claimed the kingship of France in 1337. As early as 1332 Philip anticipated a difficult succession and had his barons swear to support John should Philip die while on crusade. John's need for protection lasted through the 1340s; in 1347 his brother-in-law, Charles IV, the Holy Roman Emperor, promised to aid John if his succession were threatened.

In 1340 Edward's agents disseminated a poster containing a French translation of the Latin letter in which Edward claimed to be the legitimate heir to Charles IV, the last Capetian, who died in 1328, and assumed the royal style of King of France and England.[29] This translated letter, posted on church doors in northern France, was so inflammatory that Philip ordered all copies confiscated and all who posted it or permitted it to be posted imprisoned.

Edward's propaganda was so broadly disseminated that it affected the visions recorded in the late 1340s by Saint Bridget of Sweden,[30] an anti-French author often quoted by the English in their political writings. In one vision the Virgin Mary appeared to Bridget and contended that Philip was a legitimate king, since he had been selected by the barons of France and had not come to the throne by violence,[31] and should therefore rule France until his death. Many asserted, however, that Edward was closer to the inheritance of the throne than Philip and should be designated by Philip as his successor.[32]

Such threats to John's legitimacy may explain why the prologue and its miniature present succession to the throne as a "succession of time" rather than

a succession of blood. Such an argument could be used to defuse English claims. Other portions of the cycle focus on the same themes as Edward's propaganda, celebrating descent from Saint Louis and the idea of a crusade, while promoting France's holy kingship.

Saint Louis:

The Model Roi Très Crétien

Almost from the moment of his death, Louis IX became a model for royal behavior against whom subsequent kings were measured and often found wanting. Royal descent from Louis cut in two directions; while the canonization of a French king gave the Capetians proof that they were part of a line of rois très crétiens , Louis's life was a reproach to subsequent kings who, not gifted with sanctity, had difficulty living up to his example.[33] Nonetheless, devotion to the royal saint was strong, particularly among members of the royal house. Such patrons as Louis's daughter, Blanche; his wife, Marguerite; his grandson, Philip IV; Jeanne de Navarre; and Jeanne d'Evreux commissioned portraits of Saint Louis and cycles of his life in panel paintings, frescoes, stained glass, and manuscripts.[34] These cycles celebrated Louis IX's sanctity and the special status of the Capetians who were related to the saint.

Saint Louis played an important role in polemical discussion from the moment Philip of Valois succeeded the last direct Capetian. Philip viewed himself as the head of the Capetian house and often used references to Saint Louis, particularly during the first troubled years of his reign, to add the prestige of his royal ancestor to his own acts.[35] He ordered coinage early in his reign "of the weight and law of Saint Louis" and refrained from doctoring its composition until 1337 because of the value of its symbolic connection.[36] Between 1329 and 1331 a series of documents issued by Philip's chancery adopted the form employed by the Capetians, opening with an invocation and closing with the royal monogram and signatures of court officials. Cazelles notes that this literary form was abandoned as soon as Edward III confirmed the legitimacy of the Valois succession by acknowledging in 1331 that his homage of 1328 to the French should have been liege.[37]

While Edward continued to claim the throne of France, however, he celebrated his own descent from Saint Louis. In the 1340 letter posted in northern French churches, he stressed that he did not want to infringe on the rights of the French people, but rather he wanted to return France to the "good laws and customs which existed in the time of our ancestor [and] progenitor Saint Louis, king of France."[38] He also emphasized the need for peace in Christian countries so that a crusade could be mounted to free the Holy Land.[39] The notion of a unified crusade of the Western nations was a recurring theme that became intertwined toward the end of the Hundred Years' War with prophecies of the last world emperor.[40] When Edward's letter was written and John's book painted, however, the references to a crusade probably related more closely to claims of direct descent from Saint Louis, the last crusading king of France, rather than to claims to world empire. They refer as well to the legitimate French king's status as "most Christian king."

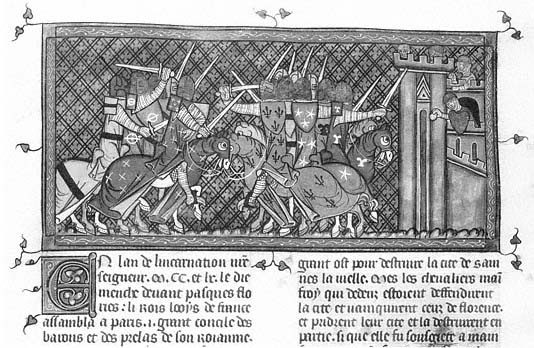

The crusading reference in Edward's letter was probably a jibe at Philip and John. As early as 1334 Philip, who had vowed to go on crusade, sent the

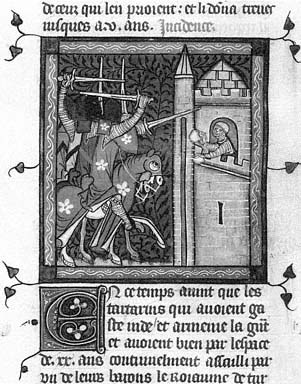

Figure 41

Assault on a castle by the Tartars. Grandes

Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G

VI, fol. 400. By permission of the British Library.

Connétable d'Eu to England to persuade Edward III to participate in the crusade that Philip had negotiated with Pope John XXII.[41] With the approval of the pope, Philip collected special ecclesiastical taxes but did not go to the Holy Land because of France's uncertain relations with England; instead, from 1335 to 1337 Philip used the funds to finance his English war.[42] In March of 1340, a little over a month after Edward's letter was written, Philip asked Pope Benedict XII for a pardon for his fiscal indiscretion. Only in 1344 was the pardon awarded by Pope Clement VI to Philip and to John, who apparently shared responsibility for this fiscal abuse.

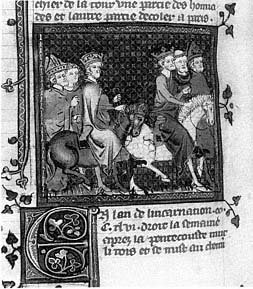

It is tempting to see the emphasis on crusades in John the Good's Grandes Chroniques (1335–40), particularly crusades in which Saint Louis participated, as reflecting the French side in the polemical war with England. Louis's crusades receive special attention in the dense cycle that illustrates John's manuscript: only six pictures in the entire manuscript subdivide chapters, and three of these occur in the crusading sections of Saint Louis's life.[43] These miniatures establish each of Louis's crusades as a holy war, provoked by pagans. The first two illustrate Louis's first crusade: one represents the dastardly behavior of the infidels (Fig. 41, assault on a castle by the Tartars); the second represents the response of the Christians (Fig. 42, the pope sends Bishop Odo to Paris; nobles listen to Bishop Odo

Figure 42

Pope sends Bishop Odo to Paris; Nobles take the cross. Grandes Chroniques de

France . British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 403. By permission of the British Library.

Figure 43

Louis receives a letter about the Holy Land.

Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library,

Royal 16 G VI, fol. 426v.

By permission of the British Library.

Figure 44

Attack of the Tartars in the Holy Land. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G

VI, fol. 427. By permission of the British Library.

and take the cross). In the third subdivision in Louis's life a pair of miniatures explains why the French became involved in Louis's second crusade, in which he died. They illustrate the arrival of a letter from the pope and then represent its contents describing attacks by the infidels (Fig. 43, Charles of Anjou in council receives a letter from the pope; Fig. 44, attack of the Tartars in the Holy Land).

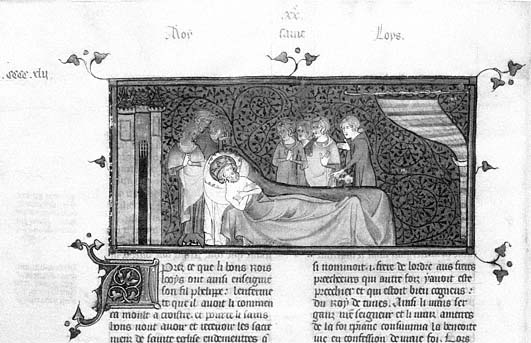

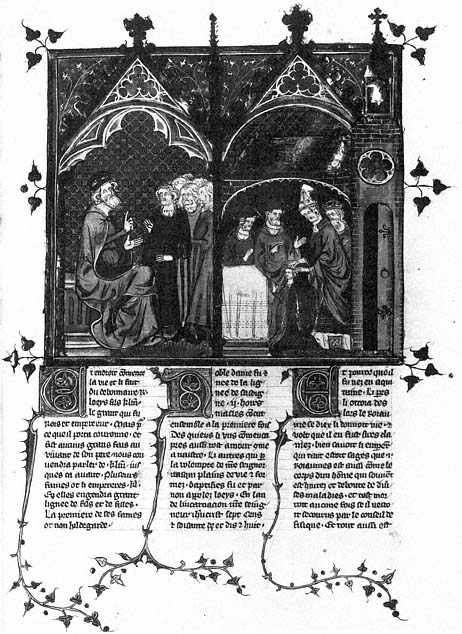

Aside from miniatures whose subjects can be classed as administrative (receptions of envoys and meetings with various heads of state; fols. 403v, 405, 406, 407, 407v, 408v), all other pictures of Louis's crusades bring out two themes: his victories in the Holy Land and his sanctity. Miniatures of Louis's triumphs in his first crusade show the battle and capture of Damietta (409v, 410v), but his religious devotion attracts more emphasis in such scenes as the pilgrimage to Nazareth (fol. 415v) or the burial of the dead after the massacre at Sidon (fol. 416v). The miniatures illustrating Louis's second crusade celebrate his sainthood more emphatically. Louis is nimbed throughout this final sequence of 10 pictures, which culminates with his instructions to his son (fol. 443v) and his death (Fig. 45).

In keeping with French policy of the 1330s and 1340s, this emphasis on Louis IX's life is less a call to a crusade than a celebration of the saintly king from whom John was descended and of the holy kingship to which John was

Figure 45

Death of Saint Louis. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 444v.

By permission of the British Library.

heir. The possibility that this celebration of descent from Louis IX may have had an anti-English component is strengthened by John's choice in 1350 to be crowned with the "crown of Saint Louis" rather than that of Charlemagne. This act was simultaneously a sign of his devotion to the saint and an affirmation of his legitimacy as successor to Saint Louis and to Philip of Valois.[44]

The Prerogatives of Holy Kingship

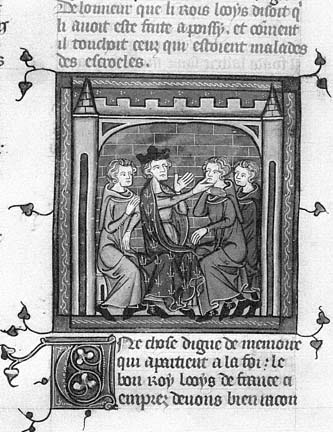

Two sets of images in John the Good's copy of the Grandes Chroniques introduce themes that were to become particularly important in the reigns of John and later Valois kings. Images in the life of Clovis refer to the sacre by the holy oil sent from God, and a rare picture in the life of Saint Louis refers to the king's role in the cure for scrofula. Both represent privileges that the French king claimed as the roi très crétien .

The right to be anointed with special oil sent from heaven distinguished the French ruler from all other rulers in Christendom and made him the equal, if not the superior, of the Holy Roman Emperor.[45] This right, which originated in the reign of Clovis, the first Christian king of France, is the subject of two large miniatures in John's chronicle. In the first (Fig. 46) Clovis routs the Germans under the protection of Christ, who gazes down at the battle.[46] The text explains that Clovis won this battle because he vowed to convert if given a victory. In the second large miniature (Fig. 47) Clovis is baptized by the holy oil brought by a dove. The only other large illustration (Fig. 48) in Clovis's life involves another miraculous sign from God. In it, messengers sent to the church of Saint Martin at Tours to ask for a sign of victory were greeted as they entered by the psalm, "Sire thou did gird me with strength for the battle. . . . Thou did make my assailants sink under me."[47] All three of these distinctive pictures celebrate the French kings' close relationship to God.

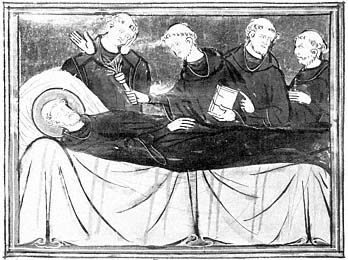

The holiness of Saint Louis's kingship is emphasized by the use of halos that focus particular attention on two sequences from the cycle of 60 pictures illustrating his life. This practice seems deliberate, since the halos have no discernible structural or textual function in these portions of the manuscript. It does not seem to be an artistic trait, since the two artists who painted these sequences did not use halos in other portions of Louis's life that they painted. Neither is it a case of mixing models from varied sources, since the scenes in which Louis wears a halo do not break down into iconographical units whose models could be isolated.

The most densely illustrated sequence begins when Louis takes the cross to go on his second crusade (fol. 436v); it continues through the series of 10 pictures that show the events that led to Louis's death in Tunis. In this sequence halos draw attention to a crusading subcycle that culminates in Louis's saintly death (Fig. 45).

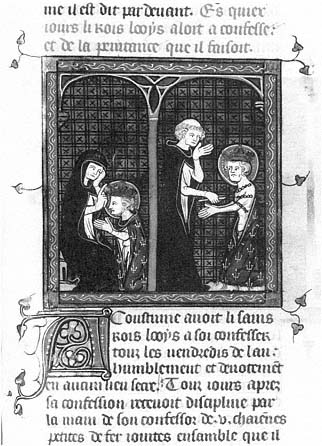

The use of halos elsewhere in Louis's life is more puzzling. Only two from a series of scenes dedicated to his saintly behavior represent Saint Louis wearing a halo: Louis attending confession and being scourged by his confessor (Fig. 49), and Louis feeding the poor (fol. 423v). Ordinarily the authority of the pictorial model or peculiarities of the artist explain such intrusions, but such is not the case here. One artist painted the whole sequence of scenes dealing with Louis's

Figure 46

Clovis routs the Germans. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 15.

By permission of the British Library.

Figure 47

Baptism of Clovis. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 16.

By permission of the British Library.

Figure 48

Miracle at Saint-Martin of Tours. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library,

Royal 16 G VI, fol. 18. By permission of the British Library.

holiness, and the two images in which Louis wears a halo do not constitute a distinct subcycle.

The best explanation for this phenomenon derives from the relationship of this sequence of miniatures to its text and to the illustrations that precede and follow it. The two pictures precede a miniature (Fig. 50) that occurs in no other copy of the Grandes Chroniques and, to my knowledge, in no manuscript predating the reign of Charles VII.[48] It represents a special prerogative given the French kings after their unction with the holy oil: the ability to cure scrofula, the disease known as "the king's evil." The picture shows Louis IX speaking as he touches the neck of a man who kneels before him; the text emphasizes Louis's devotion by describing how he introduced the sign of the cross into the ritual in order to minimize his own agency in the cure: "King Louis had the custom that while saying the words [of the ritual] he always made the sign of the cross which by the virtue of Our Lord cures the sick more than the royal dignity."[49] It is therefore likely that Louis was given a halo in the two previous scenes to reinforce God's role rather than his own in the third scene. A reader turning the pages in sequence would be struck by the lack of a halo in the picture of the cure for scrofula. The image would reinforce the textual reference to the role of Christ, rather than the king, in effecting the cure. One of the marginal glosses attests to the continued importance of this point at the time that John's manuscript was annotated: "Why

Figure 49

Louis IX at confession; Louis disciplined by his confessor.

Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G

VI, fol. 423. By permission of the British Library.

he [Saint Louis] attributes this virtue to the sign of the cross and not to the royal dignity."[50]

This celebration of Louis's miraculous powers as king emphasizes his devotion and humility, but it also has political significance, for the ability of the French kings to cure the "king's evil" was being challenged for the first time. Throughout most of the fourteenth century, the ability of the French and English kings to perform miraculous healing had been accepted as fact and as a gift shared equally by both monarchies.[51] During the Hundred Years' War, however, the ability to cure may have become a sign of legitimacy. In the late 1340s a Frenchman was imprisoned for six years because he asserted that the king of England should be king of France because he cured scrofula better.[52]

Perhaps because of the shaky political situation that existed in France, John the Good's Grandes Chroniques de France differs markedly from the book in the royal library that should logically have been its model: Philip III's Grandes

Figure 50

Cure of scrofula. Grandes Chroniques de France . British

Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 424v.

By permission of the British Library.

Chroniques (Ste.-Gen. 782). Philip III's manuscript was commissioned for him by the monks of Saint-Denis during a time of peaceful succession to the throne. Its text celebrates the royal line descended from Troy and the role of the abbey of Saint-Denis in French history. The pictures reinforce these themes in a program of just 36 images that illustrate their own texts carefully, but also establish visual cross-references intended to provide specific models of government for Philip.

The circumstances under which John's book was produced affected its content and appearance. Elements of its text and pictorial cycle suggest that it originated in the Parisian court rather than the Dionysian abbey. Its pictures support this interpretation, for their density is analogous to other commissions of John the Good and their form reflects contemporary styles in romances and saints' lives. These pictures function differently from those in Philip III's Grandes Chroniques . Although the 600 scenes relate to their texts as closely as the pictures in the earlier chronicle, the density of the cycle in John's manuscript, which illustrates almost

every chapter of the text, made it impossible to implement the kind of cross-referencing that structures Philip III's book. Instead, the book's designer sought to break up the sequence of pictures by employing variations in scale and by playing on the presence or absence of such iconographic details as halos. Several images featured in this way focus the reader's attention on themes of Christian kingship, particularly on those that would bolster John's shaky position within the new Valois line vis-à-vis his English competitor.

Chapter Four—

The Courtly Response in Manuscripts by the Master of the Roman de Fauvel

Most manuscripts of the Grandes Chroniques that survive from the mid-fourteenth century were nonroyal copies made by Parisian booksellers for a courtly audience. The owners of these books, unlike the owners of the sophisticated, self-conscious royal manuscripts, did not belong to the long line of kings descended from Troy. Their ancestors had participated in battles, advised kings, or taken part in ceremonies described in the pages of the chronicle, yet rarely had they been protagonists. These courtly patrons therefore commissioned books that reflected their own roles in history by celebrating les français as well as le roy .[1]

The earliest owners of these nonroyal books are unknown. It is therefore hard to determine whether a given program of illustration was selected because of its importance to a specific patron. It has been established, however, that many of these manuscripts were painted by the same artists.[2] A careful comparison of their cycles of illustration with those of royal commissions like John the Good's can therefore provide a clear picture of the different perceptions of history—particularly dynastic history like that of the Grandes Chroniques de France —among contemporary audiences.

The distinctive perspective of the courtly audience during the reigns of the early Valois kings can be seen in three copies of the Grandes Chroniques (Switzerland, private collection; B.R. 5; and Castres, B.M.) dating from the 1330s. They were illustrated by an artist who belonged to a group of miniaturists known collectively as the Master of the Roman de Fauvel .[3] Working for members of the nobility, this group of artists decorated a wide variety of texts: ancient and French history, romances, moralized Bibles, and saints' lives.

Little is known about the earliest provenance of the Grandes Chroniques manuscripts illustrated by the Master of the Roman de Fauvel , although all seem to have been courtly. By the 1340s the manuscript in Castres belonged to the wife of the French chancellor, and in the fifteenth century the chronicles now in Brussels and Switzerland were in the collection of the duke of Burgundy.[4] The libraires who produced them could have had little access to royal models; their lives of Saint Louis, Philip III, and Philip IV are similar to one another but different from those of contemporary royal manuscripts. For example, in all the books from this group the life of Saint Louis incorporates the French translation of the continuation of Guillaume de Nangis used by Thomas of Maubeuge in his manuscript from the 1320s.

Like Thomas of Maubeuge, the designers of these books apparently took the taste of their patrons into account by personalizing both text and pictures. Thus an unedited text describing John of Jerusalem's trip to Rome to ask for papal assistance for the Holy Land was apparently included in the Brussels chronicle to satisfy the requirements of a patron with a particular interest in this incident. Because the pictorial cycles in these manuscripts are as varied as their texts, a comparison of texts and images should cast light on the perceptions of French history by noble audiences in the mid-fourteenth century.

In analyzing the nobility's use of history, it is important to take into account the stock illustrations often used in decorating medieval books. For instance, an illustration of the baptism of Clovis, the first Christian king of France, in the manuscript in Brussels (Fig. 51) is quite closely related to a similar illustration in the Castres manuscript (Fig. 52). Although certain figures change—a queen in the Brussels version becomes a monk in the Castres version, a monk in the Brussels illustration becomes a bishop in the Castres miniature—the basic configuration is identical; it is simply expanded from its miniature format in the Castres manuscript to fill an oblong space in the book in Brussels. The similarity between battle scenes painted in the Grandes Chroniques overseen by Thomas of Maubeuge (B.N. fr. 10132) in the 1320s and those in the gathering of the Castres chronicle on which the same artist collaborated demonstrates the continuity of such models.[5]

Because so many images in the Master of the Roman de Fauvel's Grandes Chroniques are stock scenes, it may be rash to suggest that their iconography expresses any individual owner's concerns. But we can credit the patron with the

Figure 51

Baptism of Clovis. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Royale,

Ms. 5, fol. 13. Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

Figure 52

Baptism of Clovis. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Castres, Bibliothèque Municipale, fol. 11.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Castres.

selection of subject matter and with the layout of the cycle, and we can feel confident that the patron played a role in including exceptional scenes that appear in no other copies of the chronicle decorated by the Master of the Roman de Fauvel . When considered in this way, these three books demonstrate three very different popular responses to royal history.

In the Grandes Chroniques now in Switzerland the text is more revealing than its illustrations. This is one of only five copies of the chronicle to replicate the dedicatory poems that Primat addressed to Philip III in the original presentation copy.[6] Such a feature does not necessarily mean that the manuscript is royal; it may, however, indicate that the patron was particularly interested in the royal associations evoked by the text. The placement and subjects of the illustrations are conventional. All but one picture in the manuscript mark major divisions in the chronicle and draw their subject matter from the paragraphs that follow.[7] One illustration subdivides a book, a picture of Louis VII, Emperor Conrad, and others riding on crusade (Fig. 53). This one exception, however, illustrates a text that was given special notice from the beginning of the chronicle tradition.[8] The pictures in this manuscript, then, are not used so much to shape the traditional royal history for a noble audience as to reinforce a text selected for its royal overtones.

A second chronicle, now in Brussels, is written in three columns and lavishly illustrated by 129 miniatures. It traces the history of France through the death of Philip V in 1321, using distinctive text and illustrations that relate thematically to John the Good's manuscript in their emphasis on dynastic continuity but differ

Figure 53

Louis VII and Emperor Conrad depart on

crusade. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Switzerland, private collection, fol. 219v.

Photograph: The Conway Library, Courtauld

Institute of Art.

significantly in their visual expression. Indeed, most of the images in the book are more closely related, visually, to those in Thomas of Maubeuge's manuscript. And, like Thomas's images, the majority of pictures in the Brussels manuscript derive exclusively from their text. Nor do they participate in an overall restructuring of the manuscript. With the exception of a pair of large miniatures illustrating the prologue and the beginning of Louis the Pious's life, virtually all the pictures in this manuscript are two columns wide and evenly distributed.[9] Thus the special character of this cycle of illustrations is to be found not in the structure of the cycle but in its treatment of subject matter.

The most visually striking miniatures in the Brussels manuscript are the pair that introduce the prologue to the Grandes Chroniques and the life of Louis the Pious, the son of Charlemagne. Each picture is three columns wide and fills two-thirds of a page. The first (Plate 2) represents a sequence of pagan and Christian kings of France, illustrating the rubric "Here begins the chronicles of France, first of the dukes who were first there and then of the Saracen kings, and following this, of all the Christian kings and all their deeds up to King Charles, son of King Philip the Fair, and of the ancestry from whom each is descended and of their offspring."[10] This image is comparable in form to that in John's manuscript (Plate 1) but differs significantly in content. In the introductory image of John's manuscript, dukes and kings are presented on pedestals like statues to provide special models of kingship and to emphasize the length of succession to the office of king. Standing in isolation from one another, they flank an image of the

Figure 54

Charlemagne speaks to barons; Charlemagne supervises the coronation of Louis the

Pious. Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 5, fol. 151.

Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

Figure 55

Death of Saint Benedict. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 5, fol. 27v.

Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

inauguration of Pharamond.[11] In the Brussels manuscript, the kings interact with one another but are indistinguishable as individuals. This portrayal emphasizes ideas of smooth succession and continuity rather than the importance of lineage.

These nondynastic concerns also governed the selection of the other three-column miniature in the Brussels chronicle. In this picture (Fig. 54) generational continuity provides good government. On the left Charlemagne, regally enthroned, speaks with his barons; on the right Charlemagne supervises the pope's coronation of Louis the Pious as king of Aquitaine, a position that would provide him an apprenticeship in government.

Unique miniatures in the Brussels manuscript represent dramatic or miraculous events that do not involve the French king, scenes as diverse as the death of Saint Benedict (Fig. 55), King Louis of Germany torturing men to determine the justification for Charles the Bald's claim to rule (Fig. 56), or the appearance of Christ to Emperor Maurice of Constantinople (Fig. 57). Such images provide insight into the owner's interest in miracles and religious devotion—and into the personalized character of the illustration program.

The popularity of devotion to relics accounts for such scenes as the translation of Christ's robe (fol. 63), Charlemagne's prayers before the Crown of Thorns (Fig. 58), and the earliest representation that I have found in the Grandes Chroniques of the translation of the relics of Saint Louis (Fig. 59) during the reign of Philip IV. The devotional nature of this scene contrasts with the treatment of Saint Louis in John the Good's book, which places Louis's life within a dynastic frame.

Figure 56

Louis of Germany tortures men. Grandes Chroniques

de France . Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 5, fol. 184v.

Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

Figure 57

Appearance of Christ to Emperor Maurice of Constantinople.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Royale, Ms.

5, fol. 72v. Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

Figure 58

Charlemagne's prayer before the Crown of Thorns. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 5, fol. 128.

Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

Figure 59

Translation of relics of Saint Louis. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 5, fol. 327.

Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

The special text and image added to this manuscript provide an excellent example of its nondynastic aim. Between the end of the life of Philip Augustus and the beginning of that of Louis VIII is a chapter (fol. 308) illustrated by the arrival of King John of Jerusalem at Rome (Fig. 60), describing how King John came to Rome to seek help and was supported by both the pope and Frederick, the Holy Roman Emperor, whose daughter John married. The following text establishes that John was effectively the last Christian King of the Holy Land. A royal manuscript might suggest that the French king should be the successor to John or, at the very least, might call for a crusade, but the Brussels text does neither. Instead, it changes the subject and describes once again the death and burial of Philip Augustus, perhaps to provide a transition to the life of Philip's son, Louis VIII, which follows the description of Philip Augustus's death.[12]

The third manuscript, located in Castres, uses exceptional images to personalize and universalize the Grandes Chroniques . As such it is the most distinctive of the three attributed to the Master of the Roman de Fauvel . Unlike the other two, this Grandes Chroniques was frequently updated, taking its present shape in a series of four or five campaigns over a period of 20 to 25 years. As originally planned, the book was the work of two scribes who wrote the history of France through the death of Philip Augustus, a frequent terminus for the Grandes Chroniques and the endpoint for the manuscript in the Swiss private collection. This section of the chronicle was illustrated by three artists, each of whom worked on separate gatherings: the Master of the Roman de Fauvel painted all but two gatherings, one of which was the work of the first artist from the Grandes Chroniques

Figure 60

King John of Jerusalem arrives at Rome. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Bibliothèque Royale, Ms. 5, fol. 308.

Copyright Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier, Brussels.

commissioned in 1318 from Thomas of Maubeuge. A third scribe subsequently continued the history through the life of Philip V. This section was illustrated by a fourth artist, whose work can be dated to the 1340s and 1350s on the basis of costume.[13] Finally, the book was continued again in one or two stages that extend the history through the life of Philip of Valois. Spaces for illuminations were left in this section but were never filled.

This frequent updating suggests that the manuscript in Castres was as vital to its owners as royal copies of the chronicle had been to Philip III and John the Good. Thus, even if we cannot be completely sure of the identity of the original patron of this Grandes Chroniques , we may gain our clearest insights by examining how this highly valued manuscript reflects the historical perspective of its nonroyal audience.

The provenance of the Grandes Chroniques in Castres suggests that the earliest owner was a figure at court. An inscription added above the chapter describing the Battle of Courtrai (Plate 3) in the first continuation is the earliest indication of ownership. Written in a different hand from that of the text, the inscription states, "These chronicles belong to Madame Jeanne d'Amboise, lady of Revel and of Tisauges,"[14] thus providing a precise date for the inscription. After the death of her second husband, the Seigneur de Tisauges, Jeanne married Guillaume Flote, Seigneur de Revel and chancellor of France from 1338 to 1348, whose first wife died in 1339.[15] The first owner of the book was probably Jeanne, a member of her family, or her husband. Guillaume Flote may have been the owner, since he commissioned other works decorated by this artist.[16]

The placement of Jeanne's ex-libris strengthens the hypothesis that the Grandes Chroniques was given to Jeanne after her marriage. It appears above a miniature that represents one in a series of battles that Philip IV waged against rebellious Flemish forces between 1297 and 1304, when Jeanne was young. These battles were important for her family's history because her grandfather, Anseau de Chevreuse, the bearer of the oriflamme of France, the royal flag associated with Charlemagne, was killed during the campaign.[17] Had this been Jeanne's personal copy of the text, the Battle of Mons-en-Pévèle, where her grandfather was killed, would probably have been illustrated. Since the Battle of Courtrai was the only image in the book to commemorate the Flemish campaign, however, it received her ex-libris .

The Battle of Courtrai had special significance for Jeanne's husband. Guillaume Flote's father, Pierre, was one of the few loyal French who remained with Robert of Artois and died at Courtrai after the rest of the French forces fled the field. In a rare illustration to this chapter the miniature below Jeanne's signature glorifies the bravery of men like Robert of Artois and Pierre Flote. It shows the turning point in the battle, when Robert of Artois, resplendent in his arms, rode directly at the Flemish who attacked as most of the French fled.[18] In the miniature a few soldiers visible beyond Robert fight with him. It is clear that Robert and this noble minority are doomed; they will take their places with the dead soldiers who litter the ground.

The illustration to the Battle of Courtrai is thus one of those rare instances when the royal history recorded in the Grandes Chroniques merges with the history of the nobility. Such moments of convergence are rare, and representations of them

Figure 61

Abbot and monks of Saint-Denis before Dagobert.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Castres,

Bibliothèque Municipale, fol. 73.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Castres.

are exceptional. Programs of decoration for the nobility more frequently sought to illustrate universal rather than personal elements of history.

Exceptional miniatures in the pictorial cycle of Jeanne d'Amboise's book provide insight into the perception of past and present French history by the early fourteenth-century court. Of 65 miniatures, 13 are unique among those illustrating the Master of the Roman de Fauvel's manuscripts. These treat three broad themes: the first reveals the extent to which Dionysian legends fascinated a broad audience, the second examines the universal moral applications of French history, and the third concerns the relationship between the king and his vassals. Similar themes are addressed pictorially in John the Good's royal book, but Jeanne d'Amboise's manuscript approaches these themes differently, both in the concerns expressed and in the mode of presentation.

The Dionysian imagery in this manuscript centers on the two most famous royal patrons of the abbey: Dagobert and Charles the Bald. In the miniature that

Figure 62

Fair of Lendit. Grandes Chroniques de France . Castres, Bibliothèque Municipale, fol.

122v. Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Castres.

should represent Dagobert's coronation (Fig. 61) a prominent place is given to a delegation of Benedictine monks led by their abbot to confront the king. The text makes clear that this illustrates the founding of the abbey. A second image represents a later benefice allegedly given to the abbey by Charles the Bald (Fig. 62)—the Fair of Lendit. This picture, representing a shoe merchant, goldsmith, and clothes salesman at the fair, cuts its chapter in two in order to appear directly above the text explaining that Charles the Bald moved the fair from Aix-la-Chapelle to Saint-Denis at the same time that he presented a collection of relics of Christ's passion to the abbey.[19] Those who came to the fair and adored the relics were given a special indulgence. In Jeanne d'Amboise's book the merchants—part of the concrete reality that any visitor to the fair would see—are represented in the miniature rather than the legendary events or the ostentation of the relics that decorated John the Good's book (Fig. 63). Thus the emphasis would seem to be on economic reality rather than devotion to an illustrious ancestor (as in the contemporary royal manuscript). The final Dionysian picture expands the traditional representation of Charles the Bald's vision of hell (Fig. 64), which chastised him

Figure 63

Ostentation of the relics. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 163.

By permission of the British Library.

into leading a good life. A second vision (Fig. 65), in which Charles the Bald appears to a monk of Saint-Denis seven years after his death, is represented less frequently. At this appearance Charles urged the monk to persuade the king of France and the abbot of Saint-Denis to move his body to the abbey.

These Dionysian images, very different in tone from those included in royal manuscripts, may reflect a popular perception of French history. The Fair of Lendit was an event experienced by many in Paris. Jongleurs sang chansons de geste , which, like the sermons given by the monks at the fair, explained how the relics came to the abbey. Moreover, the kings featured in the Dionysian pictures of Jeanne's Grandes Chroniques —Dagobert and Charles the Bald—were the most visible of Merovingian and Carolingian rulers buried at Saint-Denis. Anyone touring the array of royal tombs in the abbey church would be struck by Dagobert's elaborate stone tomb near the altar and Charles the Bald's golden tomb in the place of honor in the choir.

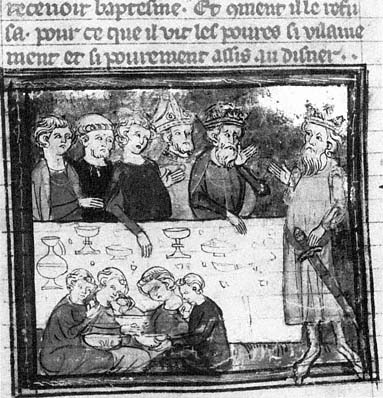

The universal moral message of French history is the theme of one of the most interesting of the unique miniatures in this manuscript—a moral exemplum drawn from the life of Charlemagne. This picture (Fig. 66) illustrates the confrontation between Charlemagne and Agolant, a Moslem leader, during Charlemagne's crusade to rid Spain of pagans. One of only two Grandes Chroniques to illustrate this theme, Jeanne's book is the only one in which the picture is carefully placed to subdivide the chapter so that it is near the text that draws a broad Christian moral.[20] The chapter recounts how Agolant decided that it

Figure 64

Charles the Bald's vision of hell. Grandes Chroniques

de France . Castres, Bibliothèque Municipale, fol. 177.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Castres.

was expedient to convert to Christianity after a series of defeats at the hands of Charlemagne's armies. He came to Charlemagne to be baptized and arrived just as the French sat down to dinner. Agolant noticed that the diners were seated in groups and inquired about their identities. Concentrating on the varied religious groups, Charlemagne explained how bishops and priests, monks and abbots, and canons regular, functioned in the religious hierarchy. When asked the identity of 12 scruffily dressed men crouching on the dirt far from him, Charlemagne responded that they were poor men, "messengers of Christ," who were fed every day in memory of the apostles. Agolant was unimpressed by Charlemagne's treatment of Christ's messengers. He refused baptism, withdrew his troops, and recommenced battle. The Grandes Chroniques draws the broad and obvious moral: "If Charlemagne lost King Agolant and his men, who would not be baptized because he saw the poor treated so villainously, what will happen on the day of judgment to those who in this mortal life despised the poor and treated them villainously? . . . Just as the pagan refused baptism because he did not see good deeds in Charlemagne, I

Figure 65

Vision of a monk of Saint-Denis. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Castres, Bibliothèque

Municipale, fol. 176v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Castres.

do not doubt that our Lord will refuse us the faith of baptism on judgment day if he sees no good works."[21]

The theme of the relationship between the nobility and the king is expressed in this manuscript through events from the life of Philip Augustus. Two illustrations represent the provisions made for governing the country when the king was absent and the punishment that awaited those vassals who rebelled against the king. The first image (Fig. 67) represents Philip Augustus speaking to councillors and establishing the testament that he made when he left for the Crusades with Richard the Lionheart. Philip's testament designated those who should rule during his absence and made provisions for a regency if he were to die in the Holy Land. The rubric accompanying this picture emphasizes not Philip's wisdom as ruler, but the effect of his action on those left behind. This scene receives a different emphasis in John the Good's book, the only other to illustrate it. Whereas the traditional rubric in John's book reads, "The testament which King Philip established before his death," the rubric in Jeanne d'Amboise's manuscript is expanded to stress the

Figure 66

Charlemagne and Agolant. Grandes Chroniques de France . Castres,

Bibliothèque Municipale, fol. 128.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Castres.

theme of good government: "How the king Philip [the] God-given arranged his testament before he left France to go on crusade and how he provided for the needs of the realm and for the profit of all the common people."[22]

Philip Augustus's provisions for the common good of his loyal subjects were matched in intensity by his punishment of vassals who broke his oath. The clearest illustration of this theme is an event in the story of the Battle of Bouvines, which pitted the French forces against those of the English king and the Holy Roman Emperor. One of the knights who made the battle possible was Ferrand, count of Hainaut and brother-in-law of the French king, who allowed the English and German forces to assemble at his chateau and allied himself with them against Philip Augustus, his liege lord. Two scenes represent Ferrand's punishment. First a standard workshop scene (Fig. 27) represents the French victory at Bouvines at which he was captured; then an exceptional image (Fig. 68) shows Ferrand being paraded in Philip's triumphal entry into Paris. The text describes the crowds berating the count on his way to Paris; it gives little attention to Philip's welcome.[23]

Figure 67

Philip Augustus's testament. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Castres, Bibliothèque Municipale, fol. 263.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Castres.

Ferrand's punishment is the exclusive focus of the miniature, which does not even include the king.

John the Good's chronicle was designed to gather suitable models of kingship for the heir to the throne and, in the process, to inspire John to be a good king like Saint Louis, whose reign ends the manuscript. John probably read the book this way. For him the events recorded in the Grandes Chroniques were living history, which affected him and in which he would participate.

The books decorated by the Master of the Roman de Fauvel present a very different view. They did not provide a model of living history to their owners, but rather testified to popular reactions to the French past. For the patron of the book now in Switzerland (private collection), possession of the royal text was most important; illustration did little to shape a personal reading of the chronicle. In the chronicle now in Brussels (B.R. 5) pictures reveal an awareness of the importance of succession and the role of such models of kingship as Charlemagne in guaranteeing it. The idea of the miraculous and the devotion to such kings as Saint

Figure 68

Count Ferrand led to Paris. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Castres, Bibliothèque Municipale, fol. 288.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale, Castres.

Louis and Dagobert, celebrated in contemporary chansons de geste and hagiography, were, however, much more important to this book than any dynastic theme. Of the three, only Jeanne d'Amboise's chronicle could be termed instructional as John the Good's Grandes Chroniques had been, but it was instructional only on the most popular and universal level. The readers of Jeanne's chronicle knew that they would probably never have a place in its pages, and perhaps as a result even the exceptional pictures in this book reinforce generalized readings of the text.