Genealogical Manuscripts

Libraires producing many of the Grandes Chroniques for the court adapted their illustrations to portray one of the many themes that shaped Philip III's manuscript: dynastic continuity. Taking their lead from the passage in the prologue that describes the "long succession" of French kings, they represent a royal genealogy that concentrates on succession to office rather than heredity.[3]

Two chronicles from the early fourteenth century (Cambrai, B.M. 682; B.N. fr. 2615) reveal the shape that such genealogical programs took. Although the provenance of these manuscripts is uncertain, textual and pictorial evidence links

Figure 16

Clovis. Grandes Chroniques de France . Cambrai, Bibliothèque

Municipale, Ms. 682, fol. 19.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale de Cambrai.

them to a courtly milieu. The chronicle in Cambrai includes the French and Latin dedication poems that appear in Philip III's Grandes Chroniques and in three later manuscripts, one of which belonged to Charles V. These textual features may indicate a royal recension of the text and suggest at the very least that the book was made for a person close to the king.[4] Artistic evidence places the second manuscript (B.N. fr. 2615) in a Parisian milieu.[5] Pictures in this chronicle relate stylistically to those by a group of artists who decorated books for the king and members of the nobility. On the basis of style, Avril dates the Grandes Chroniques in Paris to 1315–20, an attribution that is supported by a textual interpolation that provides a terminus post quem of 1315.[6]

In planning illustrations for these manuscripts, the libraires took their cue from the portion of the prologue that describes the genealogy of the French kings. The pictures repeat basic patterns, emphasizing enthroned rulers in the chronicle in Cambrai and coronations in the manuscript in Paris. The cycle from the Cambrai manuscript is the simpler. Its historiated initials, which mark normal divisions in the text, contain enthroned kings holding either swords or scepters, as for instance in the picture of Clovis (Fig. 16). The only deviation from the pattern occurs at the beginning of the third book of the life of Charlemagne (Fig. 17), where an emperor holds an orb and a scepter to commemorate Charlemagne's imperial coronation.

The cycle decorating the Paris manuscript is structured on the same principle but executed with greater sophistication. Coronations of almost every ruler of

France illustrate this book.[7] Their placement breaks down the customary structure of the text, which is normally divided into books subdivided into chapters. In this manuscript reigns of kings form textual units, and as a result the density of illustration varies radically. For instance, illustrations of the coronations of Louis III, Odo Capet, and Charles the Simple (fols. 140–141) break what normally constitutes the seventh chapter of the life of Louis the Stammerer into three segments. In other parts of the manuscript many folios separate miniatures. Thus the sequential miniatures illustrating the coronation of Louis the Pious as co-emperor by Charlemagne (fol. 90v) and the coronation of Louis the Pious as emperor (fol. 115) are 25 folios apart.

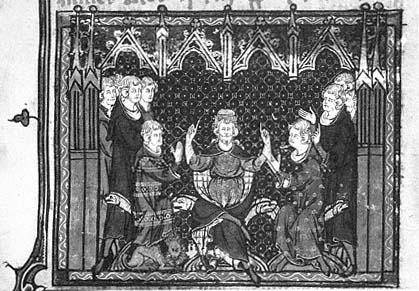

The iconography of the Paris book's cycle of illustration was carefully coordinated before the gatherings were given out to at least nine different artists.[8] Each scene incorporates details drawn from its text. Thus when the Grandes Chroniques lists three of the king's brothers attending his coronation, the miniature includes them.[9] The designer of the manuscript even elaborated the text on occasion by using elements drawn from conventions of representation to identify characters. For instance, the attributes used to distinguish Charles Martel (a large gold hat) and Pepin the Short (a lion under his feet) in the illustration of Charles Martel dividing his realm between Pepin and Carloman (Fig. 18) also appear in subsequent miniatures.[10] In the next folio Pepin is easily identified by his lion in the illustration of the coronation by Pope Stephen (Fig. 19).

These extratextual iconographic details occasionally promote the theme of dynastic continuity. Thus Pepin's and Charles Martel's costumes are used for their

Figure 17

Charlemagne. Grandes Chroniques de France .

Cambrai, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 682, fol.

140v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Municipale de Cambrai.

Figure 18

Charles Martel divides the realm between Pepin and Carloman.

Grandes Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr.

2615, fol. 72. Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Figure 19

Coronation of Pepin by Pope Stephen II. Grandes Chroniques de

France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2615, fol. 72v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

descendants. When Charlemagne supervises the pope's coronation of his two sons, Pepin and Louis (Fig. 20), Charlemagne and Pepin dress like their namesakes. Charlemagne wears the gold hat of Charles Martel, and Pepin has a lion like Pepin the Short's at his feet.

Although scenes from the Paris Grandes Chroniques incorporate specific details drawn from the text, they are essentially nonnarrative, like the miniatures in the Cambrai manuscript. Both cycles are fundamentally different from that in Philip III's Grandes Chroniques . The repetition of enthroned kings or of ceremonies of coronation in these manuscripts focuses attention on the line of kings who governed France rather than on the exploits of certain rulers who were special models for kingship.

Such genealogical programs have parallels in secular and Dionysian commissions from the reigns of Philip the Bold, Philip the Fair, and his sons. These, like B.N. fr. 2615 and Cambrai, B.M. 682, also reject the reditus as a structuring principle for representations of dynastic kingship. The series of montjoies , or markers, erected on the road between Paris and Saint-Denis was an early and public example of such a dynastic program.[11] In place from the late thirteenth century, these monuments were identical in type: each was topped by a cross and decorated by fleurs-de-lis, and each contained three niches filled with generalized representations of French kings who varied in pose from one monument to the other. The cumulative effect of these monuments emphasized the length and strength of the French line. On a trip from Paris to Saint-Denis a traveler would have seen 21 to 27 kings.[12]

Figure 20

Charlemagne supervises coronation of Pepin and Louis. Grandes

Chroniques de France . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 2615, fol. 79v.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Royal commissions for Philip the Fair placed equal emphasis on his descent. The most notable courtly commission of this sort was the decoration of the Grande Salle of the Palais de la Cité under Philip IV. There a series of labeled polychromed statues portrayed French kings from Pharamond to Philip himself.[13] Contemporary descriptions make clear that these were perceived as commemorations of the office of king. In the 1320s Jean de Jandun described the statues in terms of succession to office: "For the honor of their glorious memory, the statues of all the kings of France who occupied the throne up to the present are gathered in this place. Their likeness is so expressive that at first glimpse one would believe they were alive."[14]

Philip IV's commissions at Saint-Denis also concentrated on royal succession rather than the sequence of dynasties or the reditus . In 1306 Philip IV ordered the tombs at Saint-Denis rearranged to move his and his parents' tombs to the Carolingian side of the choir. This change merged the division of ruling houses that had been so carefully established in the 1260s.[15] Although some scholars interpret the rearrangement as an attempt to place Philip III's and Philip IV's tombs close to that of their holy ancestor, Louis IX, it also blended the lines so that the overwhelming impression on a visitor to the abbey would be comparable to that of Jean de Jandun when he faced the sculpture of the Grande Salle of the Palais de la Cité.

Royal taste for the emphasis on the long line of kings eventually affected Dionysian commissions. During the reigns of Philip IV and his sons even the monks of Saint-Denis abandoned the reditus as a means of structuring royal succession. A telling example is the third portion of Ivo of Saint-Denis's Vita et Passio (B.N. lat. 13836), part of a manuscript commissioned by Philip IV but presented to Philip V c. 1319.[16] This book merged the histories of France and Saint-Denis by appending at the end of Saint Denis's vita a historical compilation decorated by pictures of enthroned kings woven into a genealogical framework that is much more explicit than that of any contemporary copy of the Grandes Chroniques .

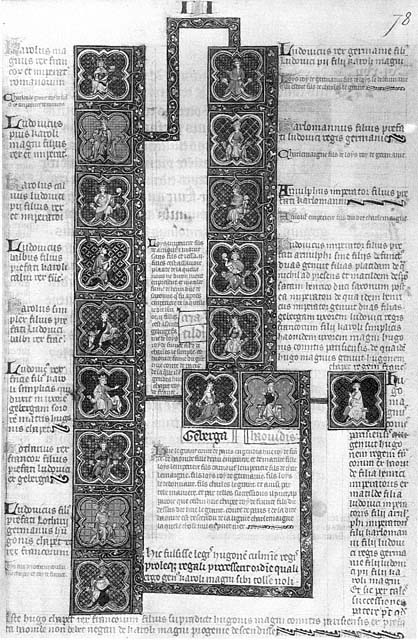

Marginal notes in a 1330s version of the Vita et Passio preserved at the abbey of Saint-Denis (B.N. lat. 5286) contribute to a reconstitution of the pictorial program in the manuscript presented to the king.[17] Several of these notes refer to images in the king's book that present special models of kingship in Charlemagne and Saint Louis or stress the importance of the French house.[18] One image in particular could have been included in the king's book only for dynastic reasons. At the end of the folio on which Hugh Capet's life is described in the later copy (B.N. lat. 5286) preserved at Saint-Denis, a cursive note describes a chart that diagrams Hugh Capet's descent from the Carolingians.[19] Although references to the chart occur in the monastery's copy, it was included only in the king's version (Fig. 21).[20] There it reinforces the Latin and French rubrics to the chapter, thus confirming Hugh Capet's legitimacy as a Carolingian.[21] The inclusion of this chart in the illustrations of the kings of France that decorate the royal book presents the reader with a pictorial genealogy of the kings of France that, like those of the Grande Salle's sculptures and contemporary genealogical Grandes Chroniques , runs unbroken from Troy to Philip V, but presents continuity of blood as well as of succession.

Figure 21

Genealogical tree for Hugh Capet. Ivo of Saint-Denis, Vita et Passio Sancti

Dionysii . Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. lat. 13836, fol. 78.

Photograph: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.