The Prerogatives of Holy Kingship

Two sets of images in John the Good's copy of the Grandes Chroniques introduce themes that were to become particularly important in the reigns of John and later Valois kings. Images in the life of Clovis refer to the sacre by the holy oil sent from God, and a rare picture in the life of Saint Louis refers to the king's role in the cure for scrofula. Both represent privileges that the French king claimed as the roi très crétien .

The right to be anointed with special oil sent from heaven distinguished the French ruler from all other rulers in Christendom and made him the equal, if not the superior, of the Holy Roman Emperor.[45] This right, which originated in the reign of Clovis, the first Christian king of France, is the subject of two large miniatures in John's chronicle. In the first (Fig. 46) Clovis routs the Germans under the protection of Christ, who gazes down at the battle.[46] The text explains that Clovis won this battle because he vowed to convert if given a victory. In the second large miniature (Fig. 47) Clovis is baptized by the holy oil brought by a dove. The only other large illustration (Fig. 48) in Clovis's life involves another miraculous sign from God. In it, messengers sent to the church of Saint Martin at Tours to ask for a sign of victory were greeted as they entered by the psalm, "Sire thou did gird me with strength for the battle. . . . Thou did make my assailants sink under me."[47] All three of these distinctive pictures celebrate the French kings' close relationship to God.

The holiness of Saint Louis's kingship is emphasized by the use of halos that focus particular attention on two sequences from the cycle of 60 pictures illustrating his life. This practice seems deliberate, since the halos have no discernible structural or textual function in these portions of the manuscript. It does not seem to be an artistic trait, since the two artists who painted these sequences did not use halos in other portions of Louis's life that they painted. Neither is it a case of mixing models from varied sources, since the scenes in which Louis wears a halo do not break down into iconographical units whose models could be isolated.

The most densely illustrated sequence begins when Louis takes the cross to go on his second crusade (fol. 436v); it continues through the series of 10 pictures that show the events that led to Louis's death in Tunis. In this sequence halos draw attention to a crusading subcycle that culminates in Louis's saintly death (Fig. 45).

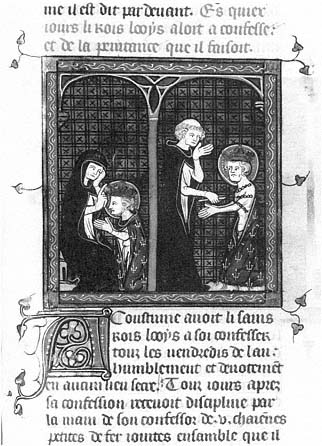

The use of halos elsewhere in Louis's life is more puzzling. Only two from a series of scenes dedicated to his saintly behavior represent Saint Louis wearing a halo: Louis attending confession and being scourged by his confessor (Fig. 49), and Louis feeding the poor (fol. 423v). Ordinarily the authority of the pictorial model or peculiarities of the artist explain such intrusions, but such is not the case here. One artist painted the whole sequence of scenes dealing with Louis's

Figure 46

Clovis routs the Germans. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 15.

By permission of the British Library.

Figure 47

Baptism of Clovis. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 16.

By permission of the British Library.

Figure 48

Miracle at Saint-Martin of Tours. Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library,

Royal 16 G VI, fol. 18. By permission of the British Library.

holiness, and the two images in which Louis wears a halo do not constitute a distinct subcycle.

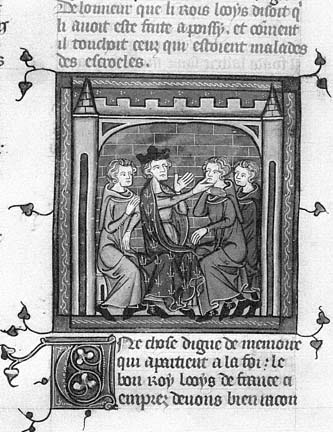

The best explanation for this phenomenon derives from the relationship of this sequence of miniatures to its text and to the illustrations that precede and follow it. The two pictures precede a miniature (Fig. 50) that occurs in no other copy of the Grandes Chroniques and, to my knowledge, in no manuscript predating the reign of Charles VII.[48] It represents a special prerogative given the French kings after their unction with the holy oil: the ability to cure scrofula, the disease known as "the king's evil." The picture shows Louis IX speaking as he touches the neck of a man who kneels before him; the text emphasizes Louis's devotion by describing how he introduced the sign of the cross into the ritual in order to minimize his own agency in the cure: "King Louis had the custom that while saying the words [of the ritual] he always made the sign of the cross which by the virtue of Our Lord cures the sick more than the royal dignity."[49] It is therefore likely that Louis was given a halo in the two previous scenes to reinforce God's role rather than his own in the third scene. A reader turning the pages in sequence would be struck by the lack of a halo in the picture of the cure for scrofula. The image would reinforce the textual reference to the role of Christ, rather than the king, in effecting the cure. One of the marginal glosses attests to the continued importance of this point at the time that John's manuscript was annotated: "Why

Figure 49

Louis IX at confession; Louis disciplined by his confessor.

Grandes Chroniques de France . British Library, Royal 16 G

VI, fol. 423. By permission of the British Library.

he [Saint Louis] attributes this virtue to the sign of the cross and not to the royal dignity."[50]

This celebration of Louis's miraculous powers as king emphasizes his devotion and humility, but it also has political significance, for the ability of the French kings to cure the "king's evil" was being challenged for the first time. Throughout most of the fourteenth century, the ability of the French and English kings to perform miraculous healing had been accepted as fact and as a gift shared equally by both monarchies.[51] During the Hundred Years' War, however, the ability to cure may have become a sign of legitimacy. In the late 1340s a Frenchman was imprisoned for six years because he asserted that the king of England should be king of France because he cured scrofula better.[52]

Perhaps because of the shaky political situation that existed in France, John the Good's Grandes Chroniques de France differs markedly from the book in the royal library that should logically have been its model: Philip III's Grandes

Figure 50

Cure of scrofula. Grandes Chroniques de France . British

Library, Royal 16 G VI, fol. 424v.

By permission of the British Library.

Chroniques (Ste.-Gen. 782). Philip III's manuscript was commissioned for him by the monks of Saint-Denis during a time of peaceful succession to the throne. Its text celebrates the royal line descended from Troy and the role of the abbey of Saint-Denis in French history. The pictures reinforce these themes in a program of just 36 images that illustrate their own texts carefully, but also establish visual cross-references intended to provide specific models of government for Philip.

The circumstances under which John's book was produced affected its content and appearance. Elements of its text and pictorial cycle suggest that it originated in the Parisian court rather than the Dionysian abbey. Its pictures support this interpretation, for their density is analogous to other commissions of John the Good and their form reflects contemporary styles in romances and saints' lives. These pictures function differently from those in Philip III's Grandes Chroniques . Although the 600 scenes relate to their texts as closely as the pictures in the earlier chronicle, the density of the cycle in John's manuscript, which illustrates almost

every chapter of the text, made it impossible to implement the kind of cross-referencing that structures Philip III's book. Instead, the book's designer sought to break up the sequence of pictures by employing variations in scale and by playing on the presence or absence of such iconographic details as halos. Several images featured in this way focus the reader's attention on themes of Christian kingship, particularly on those that would bolster John's shaky position within the new Valois line vis-à-vis his English competitor.