Six

Safety Standards for Unvented Gas-Fired Space Heaters

The final paired case study is the most interactive. The CPSC essentially made an "optional" provision of a private standard mandatory (and then later revoked the standard). The CPSC standard has been considered favorable even by some of the agency's strongest critics. The obvious question is why the private sector was unwilling to upgrade its standard sufficiently to fend off government regulation. The mystery deepens with the realization that the private standard, written by the American Gas Association Laboratory, was otherwise strict and had been upgraded significantly over the past few years. The answer reveals much about regulatory philosophy. This case strikes at the core of some fundamental differences between public and private approaches to safety regulation. The inexpensive oxygen depletion sensor (ODS)—required by the CPSC, but made "optional" in the private standard—became a lightning rod for concerns about paternalistic regulation, liability law, and antitrust law. The case highlights significant differences between the regulatory environment in the public and private sectors.

The CPSC may have been given more credit than it deserves. The rule was slow and painful in coming. Only reluctantly did the CPSC drop its original idea of banning space heaters entirely. Moreover, the agency's information is so poor that it is impossible to be sure whether the standard has generated the hypothesized benefits. Finally, in a bizarre twist that emphasizes the importance of federalism issues, the CPSC

rescinded the rule after it was deluged with petitions for exemption from preemption. In the final analysis, the case demonstrates several shortcomings of CPSC standards-setting in specific and federal regulation in general.

By contrast, the performance of the private sector was surprisingly good. The standard for unvented gas space heaters, developed decades before the CPSC was created, provided an ample degree of safety for basic operations. Moreover, the standard was strengthened over time. But AGA Labs refused to require the ODS before the CPSC made it mandatory. This position demonstrates both the significant role of regulatory philosophy and the subtle influences of product liability law. Those factors are elaborated below following an introduction to the unvented heater.

The Unvented Gas Space Heater

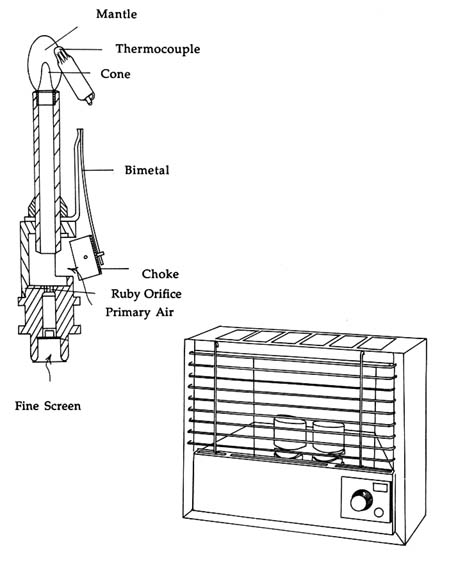

Space heaters are inexpensive, convenient, and popular with energy-conscious consumers. They are also illegal in many jurisdictions—at least certain types are. Unvented space heaters fueled by gas or kerosene are the most controversial because, unlike electric heaters and various vented heaters (including woodstoves), they discharge their combustants indoors. The long-term effects of these pollutants are unknown. The acute effects—carbon monoxide poisoning—are better understood and, under the worst circumstances, can be fatal. Owing to the differences in fuel, gas-fired heaters pose a more serious threat of carbon monoxide poisoning than those fueled by kerosene. An unvented gas-fired space heater, along with the controversial oxygen depletion sensor (discussed later in this chapter), is pictured in figure 3. In the interest of brevity, this product will be referred to as the "unvented heater" for the remainder of this chapter.

The unvented heater is a primary heating source for poor families in southern states, where many homes do not have central heating. With installation and operating costs considerably lower than those of other space heaters, and fuel efficiency of nearly 100 percent, these appliances are popular with cost- and energy-conscious consumers. They are disfavored in northern states, however, where homes tend to have central heating and better insulation. Three major producers currently account for almost all of the 180,000 units sold annually in the United States. (There were thirteen manufacturers and much higher sales before the CPSC proposed a ban on space heaters in 1975.)

Figure 3. Unvented Gas Space Heater and Oxygen Depletion Sensor

Two acute safety problems are posed by the gas space heater. The first, fire and burn hazards, is common to all heating equipment but is somewhat more serious with gas or liquid fuel sources. The primary fire and burn hazards are contact burns and clothing ignition. The burn hazard is easily mistaken for the hot radiator problem. In fact, temperatures on certain parts of the unvented heater can exceed 500° F, so the

resulting injury can be extremely serious. Lesser problems include the clearance between the heater and combustible materials, and gas explosions—less serious because they are so rare.[1]

The Invisible Hazard: Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

The second acute hazard—carbon monoxide poisoning—is the most significant. This hazard is not common to all heating equipment. It is unique to unvented (or improperly vented) space heaters fueled by gas (or, to a lesser extent, kerosene). Carbon monoxide poisoning can occur if the heater's burner is maladjusted or if the heater is used without adequate ventilation. The hazard is particularly ominous because carbon monoxide is odorless and colorless—you can be poisoned without knowing it, especially if you are asleep. Most deaths appear to be caused by inadequate ventilation, and apparently most of those are in bedrooms. It seems counterproductive to many consumers to open a window while heating a room, but ventilation is required to ensure safe use.[2]

The carbon monoxide hazard is well recognized but poorly documented. Industry trade associations do not collect injury data in any systematic way. Representatives on the relevant AGA committees are aware of the common hazard scenarios, sometimes as a result of newspaper clippings sent to the committee.[3] But the problem is not widely discussed, and anecdotes are not freely exchanged during the standards setting process.

The CPSC is the only organization that has attempted to quantify these hazards, relying on files of death certificates, reports from hospital emergency rooms, and its own in-depth investigations. The CPSC placed the unvented heater fifteenth on a list of over 350 hazardous consumer products. Except for possible publicity value, however, this designation is of dubious assistance to the agency's regulatory effort.[4] More pertinent than the total number of injuries is the character and seriousness of various components of the injury problem. How many cases of carbon monoxide poisoning occur? What are the causes and possible solutions?

Epidemiologists at CPSC have reached two relevant conclusions. The first is widely accepted: contact burns are the most common hazard associated with the unvented heater. Four-fifths of reported injuries are contact burns; the majority of these are children and elderly people who fall against the heater.[5] The second conclusion is more controversial:

unvented heaters are responsible for some seventy carbon monoxide deaths per year. This number has appeared repeatedly in briefing papers and newspaper articles over the past ten years, although its origin and accuracy are unclear.[6] Still, the number emerged with what Max Singer has dubbed "the vitality of mythical numbers.[7]

AGA Labs: The UL of Gas Appliances

AGA Labs is the premier certifier of gas appliances in the country. Best known for its Blue Star Certification Seal—which appears on furnaces, ranges, and virtually all other types of gas appliances—AGA Labs tests these products for compliance with so-called voluntary safety standards. These standards are not actually voluntary, since many jurisdictions require compliance with them through building or related installation codes.[8] AGA certification is also required by many utility companies as a condition of providing service. As a practical matter, then, it would be almost impossible to market a gas appliance in this country, at least one requiring professional installation, without complying with the "voluntary" AGA standard.

Other labs test gas appliances for compliance with the same standards as AGA Labs, but AGA plays a unique role in this private regulatory scheme. It is both the oldest and the best-recognized organization in the field. Some people refer to it as the "UL of gas appliances." The description accurately conveys AGA's stature, but not its mission or method for writing standards. AGA Labs is devoted solely to testing gas appliances, while UL's interests have branched out considerably, and somewhat controversially, over time.[9] As the creation of a trade association, AGA Labs is also looked upon with more suspicion than UL by those concerned about anticompetitive motives. The "trade association mentality," as a government attorney describes it, fosters in organizations such as AGA Labs a "bias toward protecting members of the trade" that does not, in his view, characterize "the purists, like UL."

AGA Labs stresses that it does not actually write the standards it uses to test products. "Our job at the Labs is policeman, not judge," explains the Labs' director for product certification. The safety standards that AGA Labs uses to test gas appliances, including the unvented heater, are the product of the Z21 committee of the American National Standards Institute. The unvented gas-fired space heater is a distinct species in the American Gas Association's taxonomy of gas appliances. It has its own safety standard, numbered Z21.11.2—the "Z21" denotes gas appli-

ances, the "11" is for room heaters, and the "2" signifies unvented equipment. The Z21 committee, with approximately thirty-five members, is "balanced" in accordance with ANSI requirements. Nine members represent AGA, nine represent the Gas Appliance Manufacturers Association (GAMA), and one or two members come from each of eighteen additional organizations, including the American Insurance Association, Consumers Union, the National Safety Council, the Southern Building Code Conference, UL, the General Services Administration, and the CPSC. The Z21 committee meets annually and has jurisdiction over the forty-seven standards. Some of these standards cover gas appliances; others, component parts.

AGA Labs is an unusual policeman; it is directly involved in writing the "law" it enforces. AGA Labs is the official "secretariat" of the ANSI Z21 committee. The arrangement is confusing, particularly to those who know that AGA wrote these standards before the American Standards Association (predecessor to ANSI) was formed in 1930. As recently as 1969, the year ANSI was formed, AGA Labs was recognized as the author of these standards. Many existing Z21 standards, including the unvented heater standard, were first developed under the old system. Since the power of precedent carries significant weight in most standards-writing schemes, the trade association of old may really be the co-author of any long-standing AGA standards.

Parties disagree about the extent to which standards are influenced by AGA Labs under the current ANSI system. Officially, AGA prepares meeting agendas and minutes, circulates draft standards for comments, and occasionally provides "technical input" to the subcommittees. These subcommittees, consisting primarily of utility representatives and appliance manufacturers, are responsible for proposing the actual standards and any revisions to the parent committee, Z21. There is a technical subcommittee for every standard.

The Standards Department at AGA Labs provides the secretary for each subcommittee. Other lab personnel attend subcommittee meetings to provide "technical input" and, in some instances, to draft language or proposals. Lab personnel, however, are not voting members of these subcommittees. The only decisions made explicitly by lab personnel concern the date when a standard will take effect. Decisions about content are made in the first instance by the subcommittees. Those decisions must be ratified by the Z21 committee. "If somebody wants to grumble," as an engineer at AGA Labs puts it, "they can go to the Z21 committee." Evidence of conformance to ANSI's procedural cri-

teria is subsequently reviewed by the ANSI Board of Standards Review in the same cursory fashion as most UL and NFPA standards.[10]

The ANSI Z21 committee is not a meddlesome parent. The subcommittees normally send what one AGA staff member termed "very polished documents" to the parent committee for "rubber stamping." The Z21 committee almost never overrules subcommittee actions. Most of the Z21 committee decisions are made by letter ballot. When the committee meets in person, very few people come to grumble. Occasionally the Z21 committee raises concerns or requests "further consideration" by a subcommittee. Like many parental pleas, however, these requests are often discounted, if not entirely disregarded.

The Z21 standards differ from other ANSI standards in one important respect: AGA, as secretariat, has its own elaborate procedural requirements for approving standards at the subcommittee level. These requirements are similar to ANSI's public review process.[11] Actually, they steal the show. AGA circulates "review and comment texts" of all proposed changes in standards to a diverse group of manufacturers, gas companies, and state and local officials, as well as to interested federal agency representatives. This process generates far more interest and participation than when it is publicized later by ANSI. In March 1982, for example, AGA Labs sent draft revisions of Z21.11.2 to 7 gas appliance manufacturers, 4 manufacturers of decorative appliances, 185 gas companies, and 220 state and local officials and other miscellaneous organizations. Numerous comments were sent back to AGA. When ANSI repeated the process, notification was through Standards Action, and only one party responded.

AGA Labs maintains that these gas appliance standards are ANSI standards, not AGA standards. The organization frequently asserts its "independence" from the standards-writing process.[12] This position is weakened by admissions that AGA provides financial support for the standards-writing activity. (The official line is that standards-writing is financed solely by fees for service.) Critics go much further, charging that Z21 standards are simply the product of two large trade associations—AGA and GAMA, organizations that were one and the same before an antitrust decision in 1935.

Neither "independence" nor "collusion" seems an appropriate characterization in the case of the unvented space heater. The AGA and GAMA did not agree, let alone collude, on the content of the standard. The AGA at large was split over the issue, and there were disagreements within AGA Labs.

ANSI Z21.11.2

The first standards for gas space heaters were adopted more than sixty years ago by gas utilities concerned about the safety of gas appliances. The Pacific Coast Gas Association published a standard for gas space heaters (vented and unvented) in 1924. The newly created AGA Labs followed suit two years later. In 1930 the AGA "Approval Requirements Committee" became "Sectional Committee Z21" of the American Standards Association, predecessor to ANSI. A technical subcommittee oversaw fourteen editions of the standard for gas-fired room heaters in the next thirty years. Records from this time are not readily available, but in all likelihood the standard was changed in only minor respects during these years. There were no major controversies, according to a recently retired committee member. "Things rolled along fairly smoothly for many years."

The Z21 subcommittees for gas heating appliances were reorganized in 1959, and separate committees were given jurisdiction over vented and unvented room heaters. The first standard specifically for unvented gas heaters—American Standards Association Z21.11.2—was published in 1962. It was sixteen pages long and contained both construction and performance requirements. Many of these provisions are still in effect today. Some of the construction requirements were design standards. For example, "Sheet metal air shutters shall be of a thickness not less than 0.0304 inch."[13] Others were performance-based. "Orifice spuds and orifice spud holders shall be made of metal melting at not less than 1000 F."[14] Many of the construction requirements were of a more subjective nature, however. "Burners shall be easily removable for repair and cleaning."[15] "Gas valves shall be located or constructed so that they will not be subject to accidental change of setting."[16] The performance requirements included a host of tests covering burner and pilot operation, wall and surface temperatures, valves, thermostats, combustion, and safety guards.

The standard assured that certain basic elements of safety were achieved. In other words, a heater certified to Z21.11.2 could safely be connected to a gas line and, under the right conditions, be used without incident. The standard could be faulted, however, for being less than forthcoming with warnings about the dangers that still existed. These early versions of the standard did not require any information about the need to ventilate the room in order to prevent carbon monoxide poisoning. The prevailing attitude of many manufacturers about disclosing

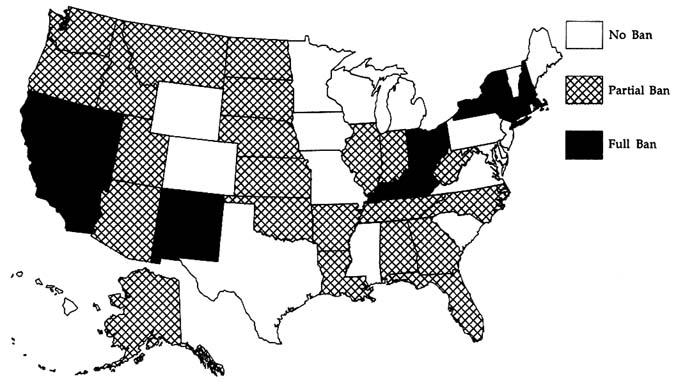

Map 1. Statewide Distribution of Unvented Gas Residential Space Heaters and Bans

information seems callous by today's standards. Warning labels and instructions were generally disfavored. The space heater standard required, for example, that "instructions provided with the heater shall include information to adequately cover cleaning of the heater." But a manufacturer took the position in 1964 that it did not have to include such instructions because the requirement was optional—in other words, the provision applied only if the manufacturer chose to provide instructions. The subcommittee agreed.[17]

The fire and burn hazards associated with the gas space heater also received short shrift in the early versions of Z21.11.2. A performance test was supposed to ensure that clothing "could not readily come in contact with flames or with parts of the heater which would easily cause ignition or charring." The test method involved exposing a piece of twenty-pound bond paper to the front of the heater for ten seconds.[18] For reasons explained later, this test bears little relationship to reality and, surprisingly, is not very effective in detecting the tendency of a heater to ignite clothing. The subcommittee did not take this hazard very seriously. The problem was periodically raised and routinely referred to a working group of some sort, where the issue languished until the cycle began anew. The triggering event tended to come from outside the committee. In 1962, for example, the NFPA forwarded a newspaper clipping concerning accidents resulting from contact with open-front heaters. AGA appointed a working group that concluded further study was necessary![19] The same conclusion had been reached by AGA working groups in 1953 and 1955. In 1970 the secretary of commerce sent the committee details of six clothing ignition cases. Another working group got its marching orders. No changes were made in the standard.

This early version of Z21.11.2 also did little to address the problem of carbon monoxide poisoning. The combustion tests included a threshold limit for carbon monoxide, but under conditions in which there is seldom a problem—when the heater is properly cleaned and adjusted. Thus, while the standard assured that the appliance was capable of safe use, it made no provision for the possibility of unsafe conditions such as poor ventilation. This is not to say that the subcommittee was unaware of the problem. The gas space heater had long been a controversial product, and there are oblique references to the carbon monoxide problem in the minutes of various meetings. The controversy predates Ralph Nader, the expansion of the tort law, and the Presidential Commission on Product Safety. The danger of carbon monoxide poisoning, particularly in northern states, prompted many utilities to oppose the product

in the 1960s. Gas space heaters were banned in Columbus, Ohio, in 1958. Several states later banned them, many others have partial bans (see map 1). Federal "minimum property standards," applicable to 15 percent of new housing in this country (but recently revoked by HUD), also prohibit the unvented heater.[20] A Philadelphia utility company argued recently it is "immoral" to allow use of the unvented heater.[21]

Whither the Unvented Heater?

The Z21.11.2 subcommittee could not ignore these developments. More than once, the subcommittee addressed the same existential question: Should Z21.11.2 exist? The answer was not necessarily a foregone conclusion. Within the AGA, sentiment at large was (and still is) divided over the unvented heater. AGA represents the distributors of gas. These companies have different interests because some are "gas-only," while others sell gas and electricity. Some do a great deal of marketing; others do not. Their interest in protecting a product such as the unvented heater varies accordingly.

Privately, some manufacturers were also less than enthusiastic about the appliance, leading one CPSC commissioner to conclude that the industry "didn't really care" about whether the heaters were banned. Some of the engineers at the AGA Labs even supported the notion of a ban. Not surprisingly, however, the committee's position has always been in favor of the gas space heater.

The stated reasons have been less than compelling. The standard should exist, the subcommittee has stated on several occasions, because without it space heaters will continue to be sold, but not necessarily with the safety levels maintained by Z21.11.2. In other words, economically speaking, the standard creates a marginal benefit. This benefit is real, however, only if the product would still be marketed without AGA approval. This is a critical and dubious assumption. AGA approval is practically a prerequisite to marketing a gas appliance. There are strong reasons to believe that the lack of an AGA standard would eliminate the product from the market, and that if it did not, manufacturers would continue to satisfy the requirements in the current standard.

The forces that motivate AGA certification would not disappear with the enactment of a limited government standard. There is no reason to think that utilities who refuse to install or service appliances without AGA certification would change their behavior in light of a federal requirement that does not even address some of their most serious

concerns (explosions, fire hazards). Moreover, pressures created by product liability law would remain unchanged. A manufacturer who chose to forgo AGA certification would run serious liability risks in relation to those hazards covered only by the AGA standard.

Relying on the distinction between product standards and installation standards, AGA Labs took the position that the existential question should be answered by someone else. Accordingly, the preface to Z21.11.2 warns: "Safe operation of a gas-fired unvented room heater depends to a great extent upon its proper installation, and it should be installed in accordance with the National Fuel Gas Code, ANSI Z223.1, manufacturers' installation instructions, and local municipal building codes."[22] In short, AGA Labs took the same position UL often does with respect to "banning" a product: it claimed to defer to use and installation codes. If NFPA will not allow an appliance, then AGA will not list it. This is the case with a cousin of the gas space heater, the so-called cabinet heater. Cabinet heaters are unvented heaters without a gas line connection. They use a gas cylinder instead. These heaters are not permitted under NFPA 58, so AGA Labs does not list them.

With the space heater, however, the most important installation code—the National Fuel Gas Code—is written by AGA Labs, further complicating the symbiotic relationship between installation codes and product standards.[23] The Fuel Gas Code recognizes the seriousness of the hazards connected with the space heater but takes the ineffectual position of "prohibiting" the appliance in sleeping quarters, sanitariums, and certain other institutions. Although an unqualified prohibition would probably keep the product off the market, the use restriction leaves enforcement largely in the hands of the consumer, who has probably never heard of the National Fuel Gas Code. The code notwithstanding, most carbon monoxide deaths apparently occur in sleeping quarters.

In reality, the existential question caused the subcommittee no existential distress. They were committed to the unvented heater. This assured certification business for AGA Labs and an imprimatur for manufacturers. As an AGA engineer remarked in response to suggestions that space heaters be redesigned to lower surface temperatures: "There is no point in pricing them out of the market if your intent is to keep them in the market." Utility representatives did not object to this unofficial intention, because even if the heaters were on the market, they could keep them out of specific gas distribution networks by refusing to hook them up and service them. Those who objected to the gas space

heater politely abstained from the discussion. A representative from Peoples Natural Gas Company, for example, responded to a proposed change in Z21.11.2 by commenting: "Peoples does not approve the installation or use of unvented heaters by our customers. I am sure that you will understand that the decision to abstain [on these revisions] was dictated by these factors and does not reflect on the fine work of the Subcommittee."[24]

The Overhaul of Z21.11.2

Z21.11.2 may never have been in danger of being scrapped, but a major revision was inevitable. Space heaters were getting a bad name, and worse yet, the federal government, for the first time ever, was considering regulating a gas appliance. The results were significant. Between 1960 and 1980 the committee added requirements for an automatic ignition system, a pilot regulator, lower surface temperatures, and improved shielding. The average retail price of the appliances more than tripled as a result, from around $50 to approximately $180. How beneficial were these requirements? Opinions vary, and the data are inconclusive.

Surface temperatures have come down slightly over the years, reducing the burn hazard to some extent. Organizations such as Consumers Union argue for further reductions. This would not prevent accidents, of course, but it would provide a longer response time before a burn injury becomes serious.[25] How that would translate into the real world of product injuries is impossible to say. There are no good estimates of the number of injuries involving surface burns, let alone how changes in surface temperature might affect them. Significantly lower surface temperatures probably cannot be obtained, however, without substantial changes in heater design. The cost and feasibility of this task cannot be estimated without research and development work. If, as manufacturers argue, surface temperatures cannot be reduced without dramatic changes in design, then it is likely that the cost would not justify the fractional change in response time to accidents. Similar uncertainty confounds any analysis of the other performance tests in Z21.11.2. The clothing ignition test, long criticized for using twenty-pound paper, was revised to incorporate the use of terry cloth. This makes the test more realistic,[26] but the real-world significance of the revised test method is impossible to ascertain given existing data. And without access to con-

fidential certification records, it is impossible to determine whether the new test resulted in actual product changes.

Perhaps the most dramatic result of these changes was elimination of a model of small bathroom heaters known to be connected with many injuries.[27] This "drop-out ban," as a trade association representative dubbed it, apparently did not improve the image of the unvented heater enough to forestall government intervention. But the industry claims that the overhaul of Z21.11.2 improved the safety of the product sufficiently to eliminate almost all carbon monoxide deaths. The CPSC disputes this claim.

The CPSC and the ODS

The CPSC first got involved with space heaters in 1974 when it received a petition from the Missouri Public Interest Research Group to ban all "space heaters." The request was apparently prompted by a tragic fire, ignited by an electric space heater, that claimed the lives of several children in Missouri. At the time, the commission did not understand the differences between the various types of space heaters (that is, electric, gas-fired, kerosene, and wood-fueled), let alone differences in styles and models. Choosing not to read the petition narrowly, and with a predisposition to grant it, the commission approved the petition "in substance" and directed the staff to figure out which space heaters should be banned.[28]

It took the CPSC several years to become familiar with the world of heating appliances. The education process was terribly frustrating for AGA Labs and GAMA. "They just didn't understand the equipment," complains a GAMA staff member who tried, with mixed success, to point out the difference between vented and unvented gas space heaters.[29] The agency's uncertainty stemmed largely from ignorance, but it was also indicative of a larger problem. Gas appliances, like most consumer products, are diverse and difficult to analyze with specificity. The CPSC's injury surveillance reporting system did not have a product code for unvented gas space heaters. Few of the newspaper reports collected through the Injury Surveillance Desk specified whether or not the appliance was vented. Even the CPSC's own "in-depth investigations," intended to compensate for data problems elsewhere, were sketchy and sometimes of questionable accuracy. Thus, even when they tried to find out specifically about unvented heaters, the staff had trouble obtaining helpful information.[30]

Eventually the CPSC singled out the unvented gas space heater, deciding that it should be banned and that vented gas heaters and other types of space heaters need not be regulated at all.[31] The overriding concern about the unvented gas space heater was carbon monoxide poisoning. "The thing that motivated the commission most over the years," according to a former commissioner, "was the actual experience of consumers as manifest by death and injury statistics." In this case, people were dying in their sleep—as many as seventy a year, according to the widely cited CPSC estimate. Industry representatives took issue with the figure. In addition to echoing familiar criticisms of the CPSC's information system, they argued that changes in the product had rendered it much safer in recent years. A representative of the Gas Appliance Manufacturers Association boldly claimed that there had been no carbon monoxide deaths involving heaters built after 1978. There is no way to prove or disprove this allegation with existing data.

Criticisms of the government's injury estimates masked a larger complaint about its motives. The unvented heater was a "politically targeted product," charged one industry representative.[32] "It isn't nearly as bad as the kerosene heater," charged another, who manufactures only gas equipment. In fact, political forces favoring regulation of the gas space heater were in motion long before the commission received the petition from Missouri. The unvented gas space heater was investigated by the FDA in the early 1970s, and by the Public Health Service before that. It was also mentioned by the Presidential Commission on Product Safety, precursor to the CPSC.

If the unvented heater was politically targeted, the CPSC missed the mark—sort of. The agency was set to ban the product when word arrived of a technological answer to carbon monoxide poisoning. The ideal solution, a carbon monoxide sensor, had always been considered far too expensive to be practical, but a second-best solution—an oxygen depletion sensor (ODS)—was touted by a European manufacturer, Sourdillion, at the CPSC hearings in 1978. Similar to a pilot flame, the ODS consists of a Bunsen burner that utilizes a synthetic ruby orifice and other precision parts to achieve uniform control of aeration and flame characteristics (see figure 3). The ODS is a delicate device; it relies on an unstable flame, also known as a metastable flame. It is stable with normal levels of oxygen but less stable as oxygen levels decrease, to a point where the flame literally lifts off and shuts down the heater.[33]

Since the CPSC was prohibited by statute from banning products for which there was a viable private standard, Sourdillion's presence at the

hearings demanded attention. Even those commissioners who personally favored a ban felt obligated to examine the ODS option. The CPSC's in-house engineers examined the device, and the agency contracted with NBS for additional research.

The most startling thing about the CPSC's analysis of the ODS is how late it occurred in the discussion of unvented heater safety. The device was introduced in 1961 in Europe. In 1972 the Z21 committee appointed a subcommittee to "follow the development of such devices and, if warranted, to develop revisions" for existing standards.[34] (They had not yet done so when the CPSC first got involved in the issue.) Remarkably, it was not until 1978, four years after receiving the petition to ban space heaters, that the CPSC acknowledged the existence of these devices. Even then, in a January 1978 briefing package, the staff informed the commission that although the device "might be technically feasible [it is] economically impractical."[35]

The European manufacturer, which boasted worldwide sales of thirty million units since 1961, begged to differ. But the success of the ODS in Europe must be put in context. European fuel gases differ from those widely available in this country, so technology that works in Europe will not necessarily work in the United States. To Sourdillion, however, adapting the ODS to this country did not pose anything more than a good engineering challenge. Still, there were two important respects in which the reliability of the ODS was called into question. First, the device does not measure carbon monoxide; it measures oxygen. Whether the relationship between oxygen and carbon monoxide was sufficiently predictable for the ODS to provide reliable protection against specified levels of carbon monoxide was a legitimate concern. Second, the metastable flame can be inhibited by dirt and lint. The dirtier the pilot, the more stable the flame and the less reliable the shutoff. How reliably the shutoff device would work in the field was a serious concern. (It was not an equivalent concern with European equipment, which requires the pilot light to be lit with each use, minimizing the amount of dirt and lint.)

Optional Equipment: AGA's Uneasy Solution

These concerns had been raised years earlier when a manufacturer requested AGA certification for a heater with an ODS device. The existing standard did not address these devices, so the engineers on the testing

floor had no guidance. AGA was on the spot. Its engineers did not know enough about the ODS to assess its reliability, let alone its desirability. The device had no track record in this country. On that basis, they decided to make the ODS an "optional requirement." For the short run, this sounds reasonable (even if oxymoronic). The solution was an uneasy one, though, because "optional requirements" appear to contradict two cornerstones of AGA/ANSI standards-writing: uniform requirements and open participation.

The certification process, both at AGA and UL, is built on a binary approach to safety regulations. Either a product receives the AGA label or it does not. AGA Labs does not want to get into the business of rating degrees of safety, putting asterisks on labels, or otherwise differentiating between products. First, the manufacturers—the lab's clients—would object.[36] Second, it might diminish the use of AGA standards. The influence of "voluntary" standards, and hence the demand for certification, is due at least in part to their ease of use. The certification process simplifies the job of building officials. No label, no approval. If asterisks are placed on labels, putting conditions or qualifications on the meaning of approval, or if safety features are labeled "optional," then the standard becomes harder to use. It cannot be applied without additional judgments about the desirability of the optional equipment or the significance of the asterisk. Once this occurs, deference to the remaining portions of the standard may also diminish. Why rely on AGA's judgment about the need for, say, automatic ignition when you are already making your own judgments about the ODS device?

Optional requirements also contradict the procedural premises of standards-writing under ANSI's committee method. AGA constantly maintains that it does not write standards, the Z21 subcommittees do. The ODS, as an optional requirement, is a clear exception. The Labs drafted the "AGA requirement" for the ODS. Such provisions are akin to UL's "desk standards." They are written by staff and not reviewed by the public. In time "AGA requirements" are usually submitted as formal revisions to standards, thereby subjecting them to the normal process of public review. This did not happen very quickly, however, with the ODS. The manufacturer who originally requested approval of the ODS device never actually marketed it. The reasons are disputed: some claim that there was no interest among manufacturers, others say that the device was not adequately proven. In either case, the ODS issue remained a theoretical one for the AGA Labs.

The CPSC Investigates the ODS

Sourdillion's presence at a Washington, D.C., hearing put tangible pressure on the CPSC. The firm apparently considered a mandatory standard the best way to create an American market for its product. The commission, committed to banning space heaters, was forced to reverse its position and examine the ODS (about which it knew practically nothing). The obvious technological question was whether the device would operate reliably under U.S. conditions. There were secondary technological questions as well. The cost of such technology was of prime concern to industry, but apparently less so to government.

To answer the basic technological question, the CPSC contracted with the National Bureau of Standards. Simple questions do not always elicit simple answers, however, particularly when a regulatory agency is asking and NBS is answering. In this instance, NBS gave a more complicated answer than the CPSC wanted. Yes, the ODS works, it concluded, but the shutoff level in the "optional AGA requirement"—an 18 percent oxygen level-might not be appropriate.[37] A higher shutoff level, such as that used in the French standard, would be more protective, since the corresponding levels of carbon monoxide would be lower. The problem is that higher shutoff levels are also more likely to cause "nuisance shutoffs" (where the heater shuts off accidentally because the cutoff point is so close to normal levels of oxygen).

The origin of the 18 percent level remains something of a mystery. Minutes of the Z21 subcommittee meetings at which the ODS was first discussed do not reflect any discussion of the adequacy of the 18 percent level. An NBS engineer who analyzed these documents for the CPSC concluded that the figure most likely came from the American Conference of Government Industrial Hygienists, a nongovernment standards-writing organization (contrary to its name).[38] Since the relevant health concern is carbon monoxide, however, and not oxygen, it would be strange indeed if the shutoff level for the ODS was selected without considering the estimated corresponding levels of carbon monoxide. More likely, members of the Z21 committee had a rough idea of the relationship between oxygen and carbon monoxide and made their decision without explicitly discussing the details. According to one frequent guest at the subcommittee meetings, "We knew what the curves would look like."

Whatever its origins, 18 percent appears to provide substantial margins of safety. The NBS tests revealed that ODS devices set for 18 percent

actually shut down at higher oxygen levels (18.2 to 20.4 percent). The corresponding carbon monoxide levels in those conditions ranged from 7 to 98 ppm, with a mean concentration of 37 ppm. A 1971 OSHA standard permits normal concentrations in the workplace of up to 50 ppm. At four times that level, the expected medical response, according to the CPSC's Directorate for Epidemiology, is a "possible mild frontal headache in two to three hours." Another twofold increase, and nausea is likely; twice again higher, unconsciousness.[39]

The CPSC staff divided on the question of whether the shutoff level in the AGA standard was adequate. The Directorate for Engineering, sensitive to the "nuisance shutoff" problem concluded that 18 percent was "adequate" and that higher levels were probably "overly conservative." The Directorate for Epidemiology disagreed, urging reconsideration of the 18 percent level because it "appears to be based largely on technical feasibility rather than on possible health effects."[40]

Whether the ODS device was commercially feasible was not a question that much interested the Program Management staff. A negative answer would have been humiliating. The proposed ban had already been tabled because of the ODS. Frustration grew as NBS engineers questioned the appropriateness of the 18 percent cutoff and industry raised the specter of nuisance shutoffs at higher levels. "We had to get a consistent story," explains one staff member. "First we said ban them, then we said no. We had to get our story straight." The story, then, was that the ODS was technically feasible and would work well with an 18 percent shutoff.

The issue never reached the commission. "Staff assured us that 18 percent was all right," recalls one commissioner. Actually, the staff was more pragmatic than it was satisfied. "Nineteen percent would have meant a five-year fight," recalls a staff member who favored the stricter level but was even more concerned about keeping things as simple and uncontroversial as possible. Eighteen percent had history on its side.

Playing Poker with the Private Sector

Once the CPSC was convinced that the ODS technology was sufficiently feasible to favor a product standard over the proposed ban, the obvious question was whether the private standard could do the job. AGA was not about to ban the space heater, but it might regulate it to the extent deemed necessary by the CPSC. The AGA standard already had an

"optional requirement" for the ODS, along with provisions covering many other hazards. If the Z21 committee would simply require the ODS device, the "voluntary" standard could eliminate the need for a government one.

The matter was not so simple from the perspective of the AGA. Industry was largely opposed to the ODS device for reasons that were never stated explicitly. Some of the resistance no doubt was based on the cost of the device. Others objected to requiring a device that was only available from one supplier—and a foreign one at that. Whatever the reason, an AGA vice president wrote the commission in the summer of 1978 that a "strong statement from the Commission as to the value of the ODS and experience with it would be needed" in order to prompt revisions in the voluntary standard.[41] There was not enough support for the idea in the private sector, even given the specter of government regulation. Changing a voluntary standard generally takes more than a year, but, warned the AGA, it takes "much longer when there is any controversy." There was in this case. To the surprise of several commissioners, the AGA seemed to be suggesting government regulation.

Assured that the device was desirable and technically feasible, the CPSC drafted a proposed mandatory standard. The action did not push the private sector too far; but the AGA made one apparently significant change. The Z21 committee added the "optional AGA requirement" to the standard at large. In other words, the ODS was now a "mandatory" part of the so-called voluntary standard. But there was a catch: the "mandatory" requirement would take effect only when AGA determined that a "suitable and certifiable device [was] available."[42]

In the eyes of the CPSC staff, it would take an additional push to make this happen. "As long as unvented heaters without ODS devices can be sold for an indefinite period," the CPSC staff argued in a memo, "the industry is not compelled to develop and test the device in a short time." Therefore, the CPSC went ahead with its proposed rule duplicating almost exactly the provisions in the AGA standard, with the addition of a specific effective date—December 30, 1980.[43] "We called their bluff," boasts one CPSC staff member.

The staff could press for an early effective date without worrying that inability to meet it would mean a de facto ban. That was what staff wanted in the first place! "Fortunately or unfortunately," as a CPSC program manager put it, "we were working with a product that was not absolutely needed by the public." In other words, the staff did not care

whether the requirement would result in a short-term ban. Apparently blind to the commercial interests of space heater manufacturers, the Economics Directorate concluded that an interruption in production would cause "no serious economic impacts."[44]

Aware that concerns about meeting the deadline would not get a sympathetic hearing within the CPSC, private interests argued against the CPSC proposal on the grounds that a government standard would displace the nongovernment one, worsening safety in areas regulated only by the private standard. These areas were significant. The AGA standard addressed surface temperatures, sharp edges, clothing ignition, and a host of other hazards unrelated to carbon monoxide. The proposed CPSC standard covered only the ODS and related labeling. But the argument against CPSC involvement depended on whether manufacturers would actually change their behavior in the event of a federal standard and forgo AGA certification on items not required by the government. That was highly unlikely, since the forces for complying with the AGA standard were unaffected by the existence of a CPSC standard. The argument was really about turf, not safety. AGA's concern was that the CPSC was embarking on a venture that might, if extended, cut into its business. And industry's concern was more about the implications for the future than about the implications of a single requirement.

There was one potential hazard that neither the CPSC nor AGA Labs addressed: chronic health effects. The issue came up during the CPSC proceedings, but the staff had no idea which elements of combustion, if any, posed potential long-term health problems. "It would have created a furor to try to address chronic hazards," recalls a former CPSC program manager. Subsequent research at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, under contract to the CPSC, suggests that one of the six tested pollutants—nitrogen dioxide—might pose a serious long-term health hazard. The CPSC has called for further studies. For now, AGA Labs is deferring to the government. "We don't have the expertise or experience to address long-term health effects," notes an AGA Labs engineer. Neither does the CPSC for that matter, ensuring that the unvented heater story is not over.

Petitions and Confusion Follow the CPSC Rule

The CPSC was determined to go ahead with the standard even though AGA Labs had all but required the ODS device. Some staff members

earnestly argued that a federal standard was desirable because the CPSC had a better warning label than AGA. But the differences were, by any measure, trivial.[45] Others felt that without a federal rule, the ODS would never be commercially adopted. One of the commissioners was determined to get back at an industry that had dared to start producing its product immediately after the CPSC lifted its proposed ban. This distrust was shared by many CPSC staff members. The commission eventually approved the rule but extended the effective date in a gesture of accommodation.

The gesture was lost on industry. Less than two weeks after the CPSC published a Federal Register notice adopting the space heater rule, GAMA petitioned the agency to revoke it. This was only the first of a plethora of petitions and other postadoption posturing that confused the commission and, years later, resulted in revocation of the ODS rule. The GAMA petition was a foregone conclusion, dependent more on the CPSC's presence than on its program. This was the federal government's first foray into regulating gas appliances. Although the rule was one that GAMA now agrees that "industry could live with," some segments of the industry could not live with the idea of government regulation. An association spokesman says that it was inconceivable that the commission could have written a rule that GAMA would not have petitioned to revoke.

Petitioning so soon after the rule was adopted was probably a tactical error on GAMA's part. To grant the petition, the CPSC would have to admit that it had made a mistake—not enough time had elapsed to argue that circumstances had changed. Positions had also hardened as a result of the just-completed rulemaking process. It was doubtful whether the CPSC would take a hard look at the petition. In fact, the staff responded to the petition with a brief memo prepared in a matter of weeks, instead of with the conventional briefing package prepared over a course of months.

The petition brought forth unexpected disagreements within the commission and within industry. The CPSC Office of Program Management could not reach a consensus. Representatives from the Engineering Directorate favored granting the petition, those in Epidemiology and Compliance opposed it, and the economists said that it would make little difference either way. Industry was similarly divided. GAMA did not want the federal government to regulate gas appliances, but some major retailers saw an advantage in federal regulation. The "carrot of preemption," as CPSC staff members often refer to it, holds

out the promise of preempting state and local regulations. For the space heater this means preempting bans in many jurisdictions, opening up a possible national market. (That is, unless the states and localities petition for an exemption from preemption—something that GAMA predicted, and that soon came to pass.)

Unwilling to revoke what it had just enacted, the commission rejected the GAMA petition. Petitions for exemption from preemption soon followed. Officials at AGA Labs who questioned the desirability of the unvented space heater persuaded the president of AGA, without the approval or knowledge of those departments concerned with marketing, to provide information to jurisdictions interested in reinstituting their bans by obtaining an exemption from preemption. Petitions poured in from cities such as Victorville, California, which argued that a ban "provides a significantly higher degree of protection from the risk of carbon monoxide than does the Commission's standard."[46]

The legal issues concerning exemption were cloudy.[47] And the practical implications of these petitions were formidable—the CPSC apparently had to rule on each petition individually. By mid 1983 there were more than two dozen petitions. On October 5, 1983, the commission proposed what looked like an easy way out: revoke the rule. Sufficient time had passed since enactment of the rule to argue that circumstances had changed. The private sector had achieved important gains; by now, the ODS was standard equipment on all space heaters. To GAMA, it was a wish come true. To some of GAMA's members, however, it meant losing the carrot. Both Atlanta Stove Works and Birmingham Stove and Range Company opposed revocation as an unfair impediment to market expansion plans undertaken after the rule was first adopted.[48]

The issue was emotionally charged within the commission, but the reasons seemed symbolic, not substantive. Since the AGA/ANSI standard required the ODS, the only practical effect of revocation was that many states and localities would reinstitute bans that might have been granted anyway through the exemption process. There were no arguable detrimental effects on safety. Still, two of the five commissioners voted against revocation. One wrote a twenty-nine-page dissent that castigated the commission for taking "such an extreme and unparalleled action."[49] The same commissioner objected so strongly to wording in the proposed revocation notice that intimated CPSC endorsement of the voluntary standard that the notice was eventually reworded. The

CPSC had (finally) deferred to the private sector, but it was unwilling to say so directly.

Summary Evaluation

Even among CPSC critics, of whom there are many, the ODS rule is widely considered to have been a desirable government action.[50] The adverse effects of the rule predicted by some did not come to pass. The ODS has become standard equipment on unvented gas space heaters, and a trade association representative confirms that there has not been a significant problem with nuisance shutoffs or consumer tampering. Moreover, there was no decrease in AGA certification after the CPSC rule went into effect. In short, there is good reason to believe that as a result of the ODS device required by the CPSC, fewer people are dying in their sleep. That is sufficient reason for the CPSC staff to conclude that the standard was beneficial. Unfortunately, there is not enough information to determine whether the averted harm is small, as industry maintained all along, or whether it is substantial (that is, as many as seventy fatalities per year), as maintained by the CPSC.

In general, the CPSC's performance was mixed. Many of the issues, such as the appropriate shutoff level, were highly technical, and the agency was not well equipped to analyze them. Delay gave way to deferral, and the technical content of the CPSC standard was eventually borrowed almost entirely from the private sector. The CPSC staff changed only the warning label and effective date of the requirement. On the former, the CPSC was insensitive to industry's concerns—product liability and adverse consumer reaction to shrill warnings—and petty in its insistence that the wording itself was an important safety issue.

The CPSC was most controversial and probably most effective in setting the date for the regulation to take effect. The staff thinks that setting an early date was a bold move that forced industry to make the ODS commercially feasible. Some industry representatives still maintain that universal use of the ODS would have been forthcoming without government intervention. That may be true, but it certainly would not have happened as quickly. Moreover, several AGA staff members speculate privately that the ODS would never have been required by AGA Labs but for the CPSC.

Outcomes aside, the process leading up to the CPSC standard was not commendable. Early in that process, the CPSC relied on political instincts

instead of information to make its decisions; and its instincts were not very good. Granting "in substance" a petition to ban all space heaters was ill informed and needlessly antagonistic. Although the CPSC did not end up banning any kind of space heater, it expended considerable goodwill in the process of reaching that decision. Beyond insensitivity, there was a streak of anti-business sentiment among the commissioners throughout the space heater proceedings. That sentiment was most evident when the commission decided to revoke its standard in favor of the private one. Publication of the revocation notice was delayed while two commissioners argued for changes in wording that would erase any affirmative statement that the CPSC endorsed the AGA standard (even though it obviously did so by implication).

On the private side, the performance of AGA Labs and ANSI was also mixed. Z21.11.2 long provided an ample degree of safety for basic operations. It also got stricter over time. Surface temperatures were reduced, and the small bathroom heater was eliminated. But before the CPSC intervened, the standard did little about the carbon monoxide problem. For years the subcommittee maintained that the ODS device should not be required because it was "not a proven technology" and had "no track record" in this country. That explanation was reasonable in 1971 when the issue first arose. Eight years later, the same explanation looked more like a lame excuse. The explanations suggested in private interviews are more convincing than those found in committee minutes. Several segments of the private sector never really believed that carbon monoxide poisoning was a product problem. Since it only occurred through misuse of some sort, they considered it a "consumer problem." Some utility company representatives and AGA Lab employees disagreed, but they respectfully kept their view outside of the standards-setting process. But the standard did address some misuse problems," including surface burns and clothing ignition, so there must have been other reasons for eschewing the ODS device. The most likely reason is product liability law. According to a representative from a gas control manufacturer, "nobody wanted to be put in the position of selling a safety device that was a safety device when you sold it but didn't necessarily stay that way." Translation: if the ODS device failed, the manufacturer would get sued. Without the device, carbon monoxide poisonings would probably be considered the consumer's fault—a rare event in the world of product safety law.[51] The perverse result, in the eyes of manufacturers, was that adding the device would increase exposure to product liability even though it would decrease product-

related hazards. This view may not hold in a court of law, but it certainly prevailed in the Z21 subcommittee.[52] Only the desire to keep the federal government from regulating gas appliance safety was strong enough to overcome the opposition of manufacturers who were unsympathetic to "the problem" and afraid of "the solution."