PART TWO

ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

6

Four Centuries of Agropastoral Change

It has widely been assumed that Khumbu agriculture and pastoralism were relatively static, traditional practices for many generations before they were transformed by a variety of changes after 1960. The crop- and stock-raising practices that Western visitors first observed in the 1950s were believed to be a traditional set of practices that had been practiced since well before 1900. As far as was known or suspected the history of Khumbu agriculture consisted of three major phases. The first of these was an early period about which little was known, but during which Sherpas presumably practiced a form of mixed agropastoralism that they had brought with them from Tibet. Following this was a period that began in the middle of the nineteenth century and lasted until the 1960s and which was characterized by the distinctive reliance on the potato as the main staple crop of the region and the nak as the mainstay of pastoralism. This period, finally, was superseded during the past thirty years by an era in which traditional crop-growing and stock-raising practices have been undermined and dramatically transformed by the far-reaching effects of tourism on regional economy and land use (Bjønness 1983; J. Fisher 1990; Fürer-Haimendorf 1984).

Sherpas do not support this view of their past. Khumbu oral traditions and oral history contradict the idea that the pre-1960, potato-based agriculture and nak-based pastoralism were a relatively static way of life for many generations. They tell a story instead of a more dynamic history of innovation and adaptation. Sherpas suggest that since the late nineteenth century few aspects of crop production or pastoralism have remained static. The crop repertoire, cropping patterns, total amount of

land under cultivation, technology, agricultural knowledge and belief, and community regulation of agricultural practices have all changed significantly.[1] Khumbu pastoralism historically has been even more dynamic than crop production, with major changes during the past century and a half in the types of stock raised, herd size, the goals and operation of local pastoral management systems, and seasonal herd-movement patterns. Yet at the same time Sherpas also testify to considerable continuity underlying these economic transformations. They dispute the contention that the changes of the past thirty years constitute a fundamental break from their long-characteristic subsistence strategies and practices. Khumbu agriculture and pastoralism are changing, but Sherpas are changing them within a context of continuing affirmation of local knowledge, cultural traditions, and valued land-use practices and lifestyles.

This chapter surveys Khumbu agricultural and pastoral history from the Sherpa perspective from the early days of settlement until the recent past. The oral traditions and history relating to changes in the subsistence economy, like those concerning the settlement history which I discussed in chapter 1, become richer in detail in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Although there are suggestions of what life was like and how it changed in earlier periods, it is only possible to analyze economic change in depth over the past hundred years. This, though, is still plenty of ground to work with—sufficient to establish both the dynamism of change in the "traditional" subsistence economy before 1960 and the processes involved. This in turn also establishes a better baseline for evaluating the changes of the recent past, some of which reflect continuing processes such as agricultural intensification, crop diffusion, and deemphasis of commercial stockbreeding which have been at work in Khumbu for a long time. I leave for chapter 10 the reassessment of what has and has not been transformed during the past thirty years by the impact of tourism.

Early Khumbu Agriculture

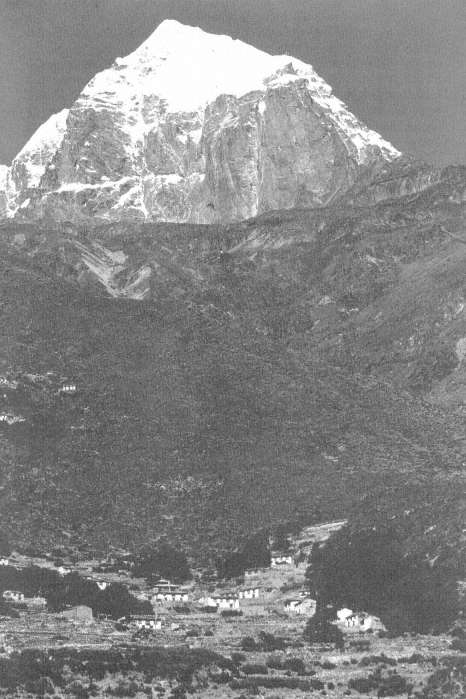

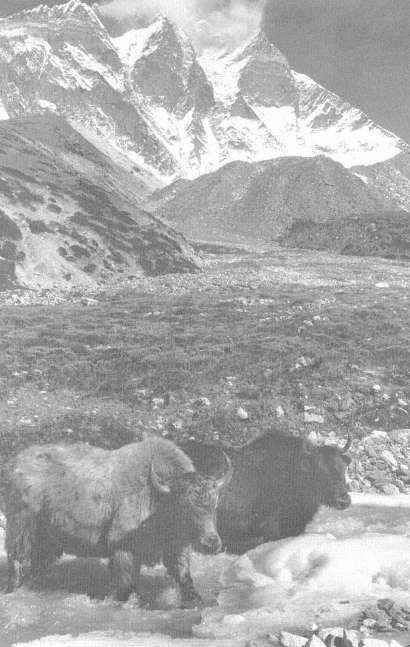

Khumbu Sherpas have probably practiced settled, mixed agropastoralism since the early days of their settlement of the region. Oral traditions about the first settlers and early life in the Bhote Kosi valley mention the growing of crops, the keeping of yak and sheep, and the use of manure for fertilizer. Not much more can be said of what was grown or how in those early years, or of when the pattern familiar for the past century and more of movement among main villages and herding settlements was established. In the early days it seems very likely that herders lived in black yak-hair tents in the summer rather than in the now-characteristic stone herding huts. Such tents figure in early stories from

Dzongnangpa's era and according to oral history were used in both the upper Dudh Kosi and the upper Bhote Kosi valley as recently as the late nineteenth century by some families. The idea that Sherpas were nomadic prior to the introduction of the potato in the mid-nineteenth century (Bjønness 1980a :61; Hardie 1957) may have come from stories of black-tent pastoralists. But abundant oral traditions testify that Sherpas have been a village-based people since the early days of their settlement of the region, and all evidence indicates that the main settlements familiar today had all been developed by 1830.

Oral traditions and oral history begin to give a firmer portrait of regional crop-growing practices in the late nineteenth century. By then the pattern of multialtitudinal crop production in the gunsas, main villages, secondary high-altitude crop-production sites, and high-altitude herding areas had already been established. All of the current main and secondary herding settlements had been settled and the crops familiar since then as the staples of Khumbu agriculture—potatoes, barley, and buckwheat—were all being grown.[2] But crop-production emphases were rather different. Potatoes were just one of several tuber crops rather than the dominant crop of the region and were not being grown at all in some of the high-altitude herding settlements or at Dingboche. Radish and turnip were being grown as major field crops, suggesting that they may have been the staple pre-potato tuber crops.[3] Buckwheat then as today was the most widely grown grain, but it was grown on a much larger scale than in the twentieth century including in places such as Tarnga, Thamicho, and Nauje where it is not grown today. Barley too was more widely cultivated and was being grown at several places in the Bhote Kosi valley.

Barley was apparently grown more widely in the nineteenth century than it has been in this century, although the need to irrigate it must have always made it of less regional significance than rain-watered buckwheat. In the late nineteenth century barley was cultivated not only at Dingboche but also at Tarnga in the Bhote Kosi valley and perhaps other places as well.[4] An elderly Thami Teng couple recalled seeing barley at Tarnga before 1920 while herding yak there. Other Sherpas recall that gembu Tsepal of Nauje was supposed to have owned barley land at Tarnga as well as at Dingboche in the early years of the century.[5]

Tarnga may have been the major agricultural center of Khumbu at one time and in the nineteenth century may have equaled or exceeded Dingboche as a barley center. There are large numbers of abandoned terraces above the settlement which were probably irrigated in an earlier time, and much of the land that is currently in potato terraces may have once been irrigated with a system that was far more complex than that employed at Dingboche. Elderly Tarnga residents have heard that for-

merly there was an irrigation ditch leading from the Chu Nasa creek north of the settlement.[6] Higher up the creek there is evidence of an old diversion and ditch that lead more than a kilometer from the creek to the head of the slope above the settlement. From here the irrigation network appears to have branched. One channel contoured along the slope to the west whereas the other descended through a flight of now-abandoned, upper-slope terraces. This system could conceivably have watered much of the field area of Tarnga.

The decline and disappearance of barley cultivation in the Bhote Kosi valley remains a mystery. There are no oral traditions describing the decline of barley growing in Tarnga. People have heard that formerly there was a prohibition on growing buckwheat there for fear that it would offend the barley. Barley, they note, has indeed disappeared from the area, and suggest that it might have declined on account of the introduction of buckwheat. Buckwheat is remembered to have flourished at Tarnga early in the century when it was a noted center of buckwheat production.[7] Beyond this they have no explanation.

Several other factors could conceivably have caused a decline of barley production at Tarnga and the abandonment there of many terraces. Crop disease and declining soil fertility might have figured in farmers' decisions; so too might the increasing scarcity of available land as the population rose, making higher-yielding buckwheat a more attractive option. Buckwheat could also have produced better crops on less fertile soils. Yet it is difficult to envision the total abandonment of barley for these reasons. Barley is still cultivated on a large scale at Dingboche despite the apparently poorer soils there and greater land scarcity than there would presumably have been in the nineteenth century at Tarnga. The cultural value and social status involved with growing barley remain strong. Yet even wealthy Sherpas with land at Tarnga have not grown even small patches of barley for many decades.

The most likely cause for the decline of barley cultivation at Tarnga may have been a failure of the irrigation network. The creek flow during May when the irrigation of barley is most critical is minor, barely enough to send a trickle of water through the ditch that supplies drinking water to the settlement. At one time more water was presumably available to feed the far more extensive earlier irrigation network. A declining flow of irrigation water could well have led to disputes over access to water and to the gradual abandonment of barley cultivation on lower-slope terraces. Once the available water declined significantly it is possible that there might not have been enough community enthusiasm to keep the out-take channel and ditches clear, and barley cultivation even on a limited scale would then not have been possible. Terraces would have been converted to a rotation of rain-watered buckwheat and

tubers, and the upper-slope terraces that had formerly been valued for their ready access to irrigation may have been considered to be too marginal in terms of soil fertility to be worth planting to unirrigated crops.

The Introduction of the Potato

It has been widely assumed that the potato reached Khumbu about 1850, but nothing is known of the original variety introduced, its source, the exact date and place of its introduction, or the pace of its diffusion within Khumbu.[8] Fürer-Haimendorf believed that Khumbu Sherpas began planting potatoes "about the middle of the nineteenth century". According to his interpretation of two oral-history accounts the new crop had diffused even to such a "conservative" village as Phurtse "soon after 1860" (Fürer-Haimendorf 1964:9). Although his analysis of these oral-history accounts may have been incorrect, as I discuss below, an introduction before the last quarter of the nineteenth century is still likely. Presumably potatoes were well established in Khumbu before 1866-1876 when Rolwaling oral traditions reported by Sacherer testify that they were brought to Rolwaling by settlers from the Bhote Kosi valley (J. Sacherer, "The Sherpas of Rolwaling: A Hundred Years of Economic Change," 1977, in Seddon 1987).

Potatoes could have reached Khumbu in the nineteenth century from several sources including Kathmandu, Darjeeling, and Tibet. William Kirkpatrick (1975:180), an early English envoy to Kathmandu, reported potatoes there in 1793 and noted that the seed potatoes had to be brought each year from the Patna region of India. They were probably introduced to Darjeeling sometime soon after the British established a hill-station settlement there in 1835 and were certainly being cultivated there by 1848 when they were noticed by Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (Hooker 1969:230). By the mid-nineteenth century potatoes could also have been grown in southern Tibet. George Bogle, who journeyed to Shigatse in 1774, had been instructed by the governor general of India, Warren Hastings, to introduce potatoes to regions through which he passed (Sandburg 1987:103). It is not known whether Bogle did establish potato growing in Tibet, but he is thought to have successfully introduced the crop to Bhutan (ibid.:103) and it might well have reached Tibet from there. Grenard (1974:247) reported potatoes in Lhasa in 1893.

The case for a Kathmandu origin for potatoes in eastern Nepal dates back to Hooker's explorations of northeasternmost Nepal in 1848. He noted that potatoes were being grown in the high-altitude fields at Yangma and at Kambachen in the Gunsa area northeast of Taplejung

where he was given "some red potatos, about as big as walnuts" (1969:247). At Yangma, a place very near the Tibet border and inhabited by "Tibetans" (possibly Sherpas or Bhotias), he remarked that

there was no food to be procured except a little thin milk, and a few watery potatos [sic ]. The latter have only recently been introduced amongst the Tibetans, from the English garden at the Nepalese capital, I believe; and their culture has not spread in these regions further east than Kinchinjunga [Kachenjunga], but they will very soon penetrate into Tibet from Dorjiling [Darjeeling], or eastward from Nepal. (ibid.:230)

Hooker apparently rejected the idea that the Yangma potatoes had come from Darjeeling, despite the proximity of the two regions, because he had not found them cultivated in the intervening area.

Fører-Haimendorf (1979:8-9) noted that Kathmandu and Darjeeling were the two most likely sources for the diffusion of potatoes into eastern Nepal. He raised the possibility that Hooker was wrong and that Darjeeling was the origin for both Khumbu and Yangma potatoes. Oral traditions he heard in Khumbu in 1953 seemed to indicate an introduction there after 1850, a date that would correlate well with earlier cultivation at Yangma if potatoes had reached eastern Nepal from Darjeeling (ibid.:9).

Both Fürer-Haimendorf's and Hooker's speculations about the origin of potatoes in eastern Nepal are based on assumptions that diffusion takes place in an orderly progression and constant pace across space. Such assumptions do not seem to be very well supported by what is known of the history of the diffusion of crop varieties in the region in the twentieth century. Diffusion is a complex process and is often difficult to predict. Other factors besides location and distance are clearly important. Peoples, villages, families, and individuals differ in their degree of receptivity to new crops. Regional patterns of trade and travel may bring one people into contact with a new crop rather than another people who may inhabit a region closer to the source. It only takes a single accidental encounter for someone to recognize a new crop and introduce it to his or her home region. Twentieth-century introductions of other potato varieties into Khumbu illustrate how important a factor chance can be. No analysis of typical Sherpa trade patterns would have concluded, for instance, that during the 1970s a potato found in a teashop on a trail near Darjeeling would come to dominate Bhote Kosi valley agriculture or that an apparently identical variety would be found just a few years later in a monastery kitchen north of Kathmandu and would rapidly diffuse from Khumjung to become the major variety grown in eastern Khumbu. Nor would it have seemed likely that in at least three twentieth-century

cases Khumbu Sherpas would have acquired new potato varieties from Sikkim, Darjeeling, and central Nepal before other Sherpa groups and Rais who lived considerably closer to those source areas, or that potatoes brought from these remote areas to Khumbu would have subsequently diffused from Khumbu into areas that might have been expected to have had them long before.

In the mid-nineteenth century Khumbu Sherpas did not frequent either Kathmandu or Darjeeling. Khumbu was politically and culturally more linked to the Tibetan world than to the Kathmandu valley and very few Khumbu Sherpas went to Kathmandu for trade or pilgrimage. Before 1850 they also probably had little to do with Darjeeling, although later in the century Sherpas went to the British hill station to trade and to work as porters and at other occupations and in the twentieth century many Khumbu Sherpas went to Darjeeling to work for mountaineering expeditions. The lack of major contact with Kathmandu or Darjeeling does not mean, however, that a single Sherpa trader or a pilgrim visiting either area could not have brought back a few potatoes to Khumbu, or that Sherpas might not have encountered the crop in Shorung or other areas where Khumbu Sherpas traded and traveled frequently and which were in closer contact with Kathmandu.[9]

As important as the introduction of the potato is to Khumbu economic history there are unfortunately no surviving oral traditions today in Khumbu which describe the event. Fürer-Haimendorf (1979:9), however, had the opportunity to hear two accounts of the introduction of the potato when he began fieldwork in Khumbu in 1953. One of these testimonies was given by an eighty-three-year-old woman of Thami who is now deceased. The other was offered by a Phurtse resident, Sun Tenzing. From these two testimonies Fürer-Haimendorf (ibid.:9) arrived at a hypothesis that the original introduction of the potato probably took place not long before the 1860s. It is worth looking more closely at both the accounts and their interpretation.

It is immediately evident that the two testimonies differ considerably in detail and that in both cases it would be useful to know more about the varieties involved and the time referred to. Whereas the Phurtse account specified the location of the first fields planted and gave a fairly specific time frame, the Thami account was extremely general. For Thami we learn only that an eighty-three-year-old woman of that village (Thami Og?) "told me in 1953 that potatoes were brought to her village by people of her father's generation" (ibid.). By itself this account does not establish very much, for the language used makes it difficult to narrow the suggested time frame. A considerable span of years could fall within the era of "her father's generation." The introduction might have occurred before her birth, during her childhood, or conceivably even

during the time before she married and left her parent's household. In the latter case, the time being discussed could be the very end of the nineteenth century.

The Phurtse account was rather different. Fürer-Haimendorf records that:

In 1953 Sun Tensing of Phortse, then a man in his middle forties, told me that as a young boy he knew an old man of over ninety of whom it was said that he had first planted potatoes on Phortse land and I was shown the plots of land on the right bank of the Imja Khola, roughly opposite Milingo, where these first potato fields were supposed to have been. (ibid. :90)

Here again, however, crucial facts are missing. The account does not, for instance, indicate how old the man referred to was at the time he planted these potatoes, which variety of potatoes he planted, where he obtained them, or how long it was until potatoes were planted in the village of Phurtse itself.

In 1985 I had the opportunity to seek these details from Sun Tenzing, with whom I had a number of discussions. According to Sun Tenzing a man named Zoa Dolma did indeed introduce a new variety of potatoes at Tsadorji, a gunsa settlement east of Phurtse on the northern, right bank of the Imja Khola and across the river from Milingo. Zoa Dolma had brought nine small, long, white potatoes to Khumbu which he said that he had obtained from Darjeeling and which he believed had come from Belait (England). This variety, which is today most often referred to as a type of kyuma, was therefore also called riki belati (English potato) by many people. He brought this potato to Khumbu, however, half a century later than Fürer-Haimendorf had supposed. The potato variety had not been introduced long before Sun Tenzing's birth but when he was a boy of about five years of age, around 1914. At that time Zoa Dolma had been in his fifties, for in his earlier account Sun Tenzing had meant to convey that Zoa Dolma would have been in his nineties had he been alive in 1953 when he had told his story to Fürer-Haimendorf. Equally as startling, in the context of further questioning he also pointed out that while Zoa Dolma had brought the first kyuma or Belati to the Phurtse area he had not introduced the first potatoes there. Before the long white potato was introduced by Zoa Dolma, he noted, Phurtse villagers were already planting a small, round potato known as riki koru (white potato).[10] . The introduction of this potato took place before his birth and he knew nothing of the circumstances or date. I was not able to uncover any of these details from other Khumbu Sherpas either.[11]

Table 20 . Khumbu Potato Introductions | |||

Variety | Period | Source | Khumbu Site |

? | mid-19th century? | ? | ? |

Koru | late-19th century? | ? | ? |

Kyuma | late-19th century? | ? | Thamicho? |

ca. 1915 | Darjeeling | Phurtse | |

Koru 2 | 1920s? | 9 | Phurtse |

Kyuma 2 or 3 | 1930s? | Lazhen, Sikkim | Thami Teng |

Moru | 1930s | Lazhen via Pharak | Thami Og |

1930s | Lazhen via Pharak | Khumjung | |

Kunde | |||

Seru | 1973 | Darjeeling | Yulajung |

Pare | |||

1976 | Singh Gompa | Khumjung | |

Bikasi | 1981 | Phaphlu | Nauje |

There were thus apparently several early introductions of potato varieties to Khumbu (table 20), at least one of which came from Darjeeling. The earliest variety was introduced before 1900 and was being cultivated at least several decades earlier, if Sacherer is correct in her hypothesis that potatoes reached Rolwaling from Khumbu by 1876 ("The Sherpas of Rolwaling: A Hundred Years of Economic Change," 1977, in Seddon 1957). But the original date and source of introduction is more uncertain today than ever.

Early Twentieth-Century Agriculture

By the beginning of the twentieth century the potato was apparently being grown in all Khumbu villages and in most of the secondary sites where it is grown today.[12] By the 1920s, and perhaps for quite a while earlier, kyuma was planted in the Bhote Kosi valley throughout the altitudinal range from the low gunsa to high phu. In the Dudh Kosi valley it was grown not only in the main village of Phurtse but also in Na and other high-altitude areas east of the river (although apparently it was not cultivated at west-bank sites such as Luza and Dole where today it is grown on a small scale). Other potatoes were also being grown widely. But although widespread and important to regional agriculture and household subsistence, the potato had not yet come to dominate Khumbu crop production in the way that it would a few years later and

does today. At this time potatoes were being grown on less than 50 percent of the cultivated area and indeed were only one of several tuber crops rather than the sole tuber grown. Elderly Sherpas maintain that during their youths (ca. 1910-1925) four crops were important in Khumbu: barley, buckwheat, potato, and radish. A fifth crop, turnip, was then being grown on a small scale. In most of Khumbu potatoes were less important a crop in the first part of the century than they have been in recent decades. In the Bhote Kosi valley there are reports that radish and turnip were grown on as large a scale as potatoes were in Thami Og and Thami Teng and that unlike today large areas of land were also in buckwheat. Estimates of the amount of buckwheat cultivation vary from half of all land in Thami Teng and Tarnga to perhaps only a quarter of the cultivated area of Thami Og. Radish was also being grown at Tarnga as a major crop, and the area was then considered to be excellent for radish growing just as it is for potato cultivation today. From Phurtse there are also reports that in the early decades of the century the potato was just one of several tubers, not the most important one. In Khumjung, by contrast, several elderly Sherpas remember that even during the 1920s the potato was the main tuber, and by then it was the major crop of Nauje and was being monocropped by many families.

Not one but rather three potato varieties were important in this era: the long kyuma whose introduction to the Phurtse area was discussed by Sun Tenzing, the early, round, white potato grown there (henceforth referred to as koru ), and a second variety of white, round potato (koru 2 ) which was apparently introduced after kyuma in the 1920s.[13] These varieties seem to have diffused at different paces in different valleys. Kyuma, for example, was evidently grown decades earlier in the Bhote Kosi valley than at Phurtse, for Thamicho Sherpas older than Sun Tenzing do not remember the introduction of kyuma during their lifetimes and have not even heard stories about it from their parents. The same is true in Khumjung and in Nauje.

Many elderly people remember both kyuma and koru 2 as the potatoes of their youths.[14] Kyuma was higher yielding and more reliable, although it was also notorious for producing extremely poor crops in bad years and for being highly susceptible to devastating blight infections. Many farmers recall times when a full day's work at harvesting kyuma would not yield enough potatoes to serve the work crew for lunch. Accounts about the productivity of kyuma, however, are inconsistent, for the variety did supplant the earlier koru and was still grown on at least a small scale in much of Khumbu until about twenty-five years ago. Good harvests are also reported, and clearly some families produced surpluses of kyuma. Some dried kyuma tubers were even exported to Tibet on a small scale.[15] That farmers remember the productivity of

kyuma differently may reflect differences in experience as well as in memory. Harvests could have been better in some areas and fields than in others due to differences in local soil and microclimatic conditions, altitude, disease problems, seed stock, or planting and manuring practices. Some Sherpas may tend to best remember the disastrous years and others the good ones. Some may best remember the variety from more recent years when it may have produced more poorly than it formerly did, possibly reflecting a loss of disease resistance or a regional decline in soil fertility. And others may base their evaluation not on productivity per field but on recollections of harvest size relative to family requirements, an equation that would have been different in earlier periods when so many families spent the winter outside of Khumbu on trade and pilgrimage journeys to lower regions of Nepal. Certainly on a Khumbu-wide level a surplus would have been achieved earlier in the century at a much lower level of regional production than at present, for the population of Khumbu was much smaller then and mostly only resident in the region for part of the year, and locally grown potatoes were not also consumed by thousands of tourists as they are today.

The Potato Revolution Reexamined

It has been commonly assumed that the potato was widely and quickly adopted throughout the region and that this radically transformed local agriculture in the nineteenth century in ways that also had major implications for regional demographic and sociocultural change. As already mentioned Hardie has suggested that before the potato was introduced Sherpas were nomadic pastoralists, a view that has been recently echoed by BjØnness (BjØnness 1980a ; Hardie 1957) whereas Fürer-Haimendorf remarked that "it is difficult to imagine conditions before potatoes found their way into Khumbu" (1979:8). Fürer-Haimendorf ascribed to the adoption of potato cultivation both a population boom and a new level of prosperity that made possible a flowering of Sherpa culture in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries which included the building of an unprecedented number of temples, shrines, and religious monuments and the founding of the region's first monasteries (ibid.:10-11).

Links between the Asian and European adoption of New World food crops and major population gain have been noted in a number of parts of the world, including the adoption of potatoes in Switzerland (Netting 1981), and maize in Nepal (MacFarlane 1976). Fürer-Haimendorf attributed a similar growth of population in Khumbu to potatoes, noting that

the population of Khumbu was a fraction of its present size until the middle of the nineteenth century and there can be no doubt that the great

increase of the last hundred years coincided with the introduction and spread of the potato. . . . No great imagination is required to realize that the introduction of a new crop and the spectacular increase in population must have been connected. (1979:10)

Even leaving aside for the moment the basic question of the degree to which potato cultivation transformed Khumbu agriculture in the nineteenth century, it seems that this issue deserves further exploration for the data on which to base such conclusions are rather slender. Indeed, the only available data on regional population size during the entire period from 1800 to 1957 are Fürer-Haimendorf's count of Khumbu households in 1957 and a count that he derived from 1836 tax documents (1979:5, 11,118). The 1836 document lists only 169 households in Khumbu whereas in 1957 the count was 597. The regional difference of 428 households established over this 121-year period represents the supposed major population growth that has been presumed to have been precipitated by the introduction of the potato in-the mid-nineteenth century. This tripling of the population (assuming that the average regional household size was similar throughout this period and that the number of households was tallied equally well on both occasions) is roughly comparable to some estimates of the population growth during the same period in Nepal as a whole, where demographic change is also believed to have been related to agricultural innovation, the introduction of maize, and the diffusion of the practice of growing irrigated rice in permanent terraced fields (MacFarlane 1976).[16]

Although the potato (along with increased trade for grain) undoubtedly provided the means to support the higher regional population density that developed after the early nineteenth century it remains premature to assert that the adoption of the crop caused this population growth. It is not clear how much of the increase in regional population can be attributed to natural population growth and how much is due to immigration. Natural rates of population increase may indeed have been raised by higher food availability and better nutrition, which in turn may have lowered mortality rates, an argument that Netting (1981) has made for the introduction of the potato in Switzerland. But it is also certain that a great deal of the regional population growth in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries has reflected migration from Tibet, as is indicated by the high percentage of Khamba households in the region in 1957. According to Fürer-Haimendorf's 1957 data (1979:102-104) (and assuming that at least half of Nauje's households then were Khamba) at least 45 percent of the households in five of the eight main Khumbu villages were Khamba immigrants from Tibet. This means that the number of Sherpa households in Khumbu less than doubled over the 121

years from 1836 to 1957. This does not seem like a major population boom. It may, however, still represent a significant increase in population growth rates over earlier centuries. And it may also be that greater potato cultivation was a factor in the increased immigration during this period. Surplus Khumbu food production and the ability to pay wage laborers in food, for example, would have helped create a regional economic climate attractive to immigrants. But a great number of other factors were also very likely involved and the role of the potato in fostering immigration should probably not be overly stressed.

Beyond the issue of the degree of natural population increase there is the more fundamental question of whether the potato was at the center of a revolution in agricultural production in nineteenth-century Khumbu. I have suggested that the adoption and diffusion of potatoes was not as rapid as had been assumed. The potato-based agriculture familiar to foreign visitors since the 1950s was not universal in Khumbu even earlier in this century, much less in the nineteenth. The potato's rise to preeminence in Khumbu agriculture was a much more complex and lengthy process than has been thought. Not only was the area in potato cultivation during the late nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries apparently considerably less than that planted to the tuber during the past fifty or sixty years, but yields were also apparently lower and poor harvests due to disease more common.

The initial diffusion of the potato was still in progress as late as the 1920s and in at least one important crop-producing settlement there remained powerful resistance to the adoption of the new crop. At Dingboche at that time the planting of potatoes was forbidden out of fear that the crop might offend the barley.[17] The ban was upheld into the twentieth century by community understanding (a community which then comprised individuals from at least four Khumbu villages). Gembu Tsepal of Nauje, Khumbu's major political leader of the time and a large landowner at Dingboche, and his son and successor gembu Pasang are both said to have been particularly concerned with upholding this ban.[18] This attitude toward potatoes was not universally shared by Dingboche residents, and the lama Kuyung Rinpoche is said to have moved from the area after a conflict with gembu Tsepal over potato planting. Eventually the degree of community agreement on the ban deteriorated to the point that it was no longer enforceable. But it was only in about 1925 that Dilu, the mother of the powerful Kunde pembu Ang Chumbi, precipitated the abandonment of the ban by advising other women at Dingboche to plant whatever they wanted to, insisting that gembu Pasang had no authority to tell them what they could or could not plant in their own fields.[19]

The process of the adoption and diffusion of the potato thus did not

take place overnight in Khumbu, but involved incorporating the new tuber in an earlier cropping complex where it supplemented but did not immediately replace tubers cultivated earlier. Adoption of the new crop involved the development of new knowledge and new beliefs, including the abandonment of a belief that potatoes threatened barley yields and the invention of community measures to guard against devastating outbreaks of late blight. Not one but several different introductions of different varieties of potatoes were involved, and although the process of adapting the new cultigen to local agricultural patterns had advanced considerably even as early as the beginning of the twentieth century, the potato did not become the mainstay of Khumbu agriculture until the widespread cultivation of a newer, higher-yielding variety, the red potato, in the 1930s.

This reevaluation of the historical process of the adoption of the potatoes has significance for the second part of Fürer-Haimendorf's potato-revolution thesis as well, the idea that there was a connection between the adoption of the potato and the flourishing of religion in Khumbu. According to him:

the foundation of monasteries and nunneries as well as the construction of new village temples and many religious monuments have taken place within the last fifty to eighty years. This points to economic events which favoured a sudden spurt of non-productive activities and in my opinion there can be little doubt that these events were brought about by the introduction of the potato and the resulting increase in agricultural production. (1979:10-11)

Here too, however, a more complex process appears to have been involved, and the role of higher-agricultural yields may have been relatively minor. Closer examination is necessary of the circumstances of the construction of religious buildings and monuments, and especially of the sources of capital and labor which made this possible. Labor for these projects seems to have been, then as now, primarily volunteer labor from nearby communities.[20] The ability of communities to mobilize this labor is based on whether local leaders can inspire participation or demand it by virtue of their offices. There is no direct link beteen local food supplies and the building of religious monuments. Even the availability of leisure time is not really an issue, for in the Khumbu agropastoral system there has long been a substantial part of the year in which there are no pressing demands. Khumbu life is built on the basis of a considerable amount of leisure, and the development of the local festival cycle can only be understood in this light. The establishment and maintenance of monasteries, temples, and monuments, however, also

requires substantial capital, for institutions must be endowed, specialists employed in their construction and sometimes in their maintenance, and many precious materials obtained for building and blessing the shrines. Yet here a larger role was often played by a few wealthy individuals rather than by the community as a whole. These sponsors were not men who had become wealthy as a result of potato growing, but for the most part were large-scale traders in other merchandise. In some cases they were not even Khumbu Sherpas: Shorung Sherpas were especially important in the original establishment of the Tengboche monastery (see Ortner 1989)[21]

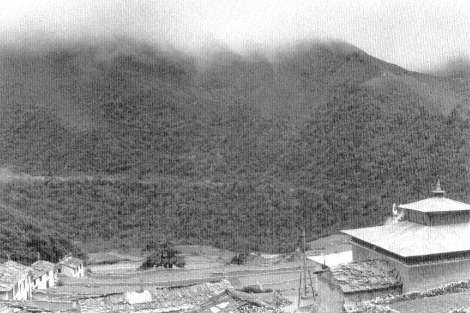

There is a problem too with the chronology of the development of monumental religious architecture in the region. It is not entirely accurate to emphasize the post-1880 period only, for most temples, chortens, and smaller religious monuments were actually established earlier. All of the village temples other than that at Nauje date to 1830 or earlier. Almost all the large chortens were built before 1880 (the main exceptions are two smaller chortens at Khumjung, one of which dates to the 1920s and the other to 1984, and three chortens in the Bhote Kosi valley). Most major mani walls (religious monuments composed of slabs of stone into which have been chiseled prayers and sacred texts) also predate 1880, although parts of the Khumjung mani wall and the mani wall at Tengboche were built after 1915. Most of the prominent expressions of religion faith in the Khumbu landscape thus seem to have been there well before the potato came to be a central focus of local agriculture in the early twentieth century. It may be that both before 1880 and since then the galvanizing force for the construction of religious monuments has not been the potato but rather the leadership of charismatic individuals who were able to inspire the financial support of well-to-do Sherpas and mobilize the volunteer labor of entire communities. And rather than a single period of major elaboration of monumental religious architecture there appear to have been a number of such periods stretching far back into Khumbu history.

Although the introduction of the potato may not have immediately been the seminal event in Sherpa history as has been assumed, it was nevertheless an important agricultural innovation that ultimately had far-reaching impacts on land use. As potatoes began to be more widely cultivated in the late nineteenth century they must have begun to increase regional agricultural production while at the same time lowering the amount of land required to meet household subsistence requirements. They provided a means of agricultural intensification, and the Sherpa response to this possibility may account not only for historical shifts in cropping emphases but also for changes in the area in crops and the abandonment of some fields in many parts of Khumbu.

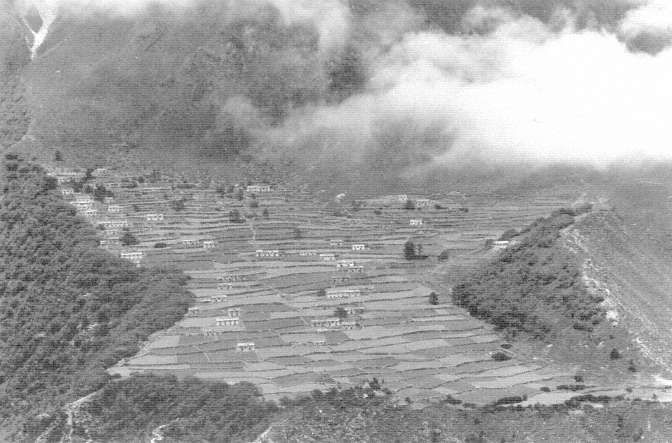

Abandoned Terraces

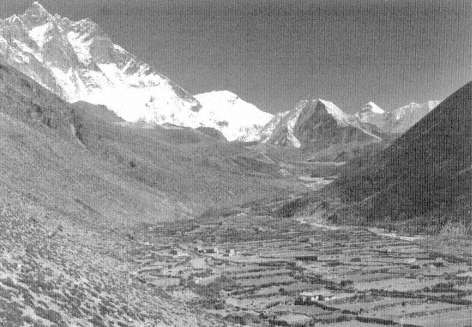

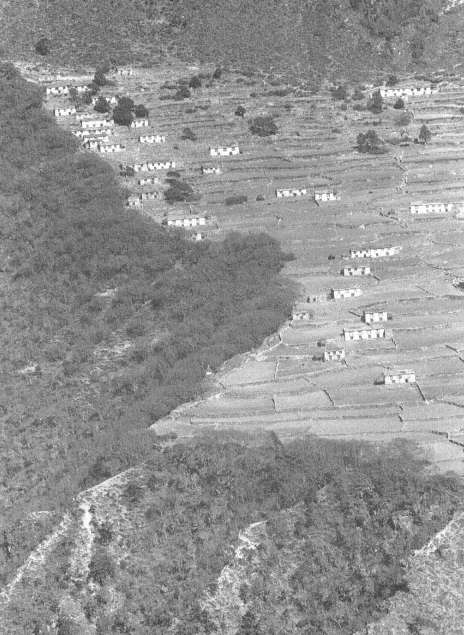

By the late nineteenth century a great deal of land was under cultivation in Khumbu despite the relatively light (even by Khumbu standards) population density. In the Bhote Kosi valley more land seems to have been cultivated during the nineteenth century than has been in production since, a phenomenon reflected in the considerable amount of terraced cropland there that has been abandoned for many decades. Although some of these old fields were returned to cultivation later, a great many have never been reclaimed.[22] Abandoned terraces are also found today in widely scattered sites throughout much of Khumbu, as indicated in map 14. Table 21 identifies sites with abandoned terraces and attempts a rough estimate of the periods when different sites were taken out of cultivation.[23] The most extensive abandoned areas are located in the Bhote Kosi valley. It is clear from this map that there is an extraordinary number of sites with abandoned land in this part of the region and that these areas are situated through much of the altitudinal spectrum of Khumbu farming. More than forty terraces were abandoned at Tarnga. At Samde much terraced land has been neglected and there are the ruins

Map 14.

Abandoned Terraces

Probable Period Abandoned | |||||

Site | Pre-1900 | 1900-1930 | 1930-1960 | Post-1960 | |

Bhote Kosi Valley | |||||

Thengbo | x | ||||

Kure | ? | ||||

Marulung | ? | x | |||

Lungden | x | ||||

Tarnga | x | x | |||

Yulajung | x | x | |||

Thami Teng | x | x | |||

Thami Og | x | x | |||

Leve | x | x | |||

Pare | x | x | |||

Samde | x | x | x | ||

Thomde | x | x | |||

Tesho | ? | ||||

Samshing | ? | x | x | ||

Tashilung | ? | x | x | ||

Nyeshe | ? | x | x | ||

Phurte | ? | x | |||

Jangdingma | ? | x | |||

Mishilung | ? | x | |||

Imja Khola Valley | |||||

Pangboche (upper west side) | ? | ||||

Pangboche (near Milingo bridge) | ? | ? | |||

Pangboche (west of Shomare) | ? | ||||

East of Shomare | ? | ||||

Orsho | x | ||||

Across the river from Orsho | ? | ||||

West of Dingboche | ? | ||||

Dingboche | x | ||||

Dudh Kosi Valley | |||||

Phurtse Tenga | x | ||||

Kele | x | ||||

Dole | x | ||||

Machermo | x | ||||

Shomare | x | ||||

Charchung | x | ||||

Na | x | ||||

Phurtse | x | ||||

Dawa Futi Chu (east of Phurtse) | x | ||||

Khumjung (east of village) | ? | ||||

Kenzuma (west of settlement) | x | ||||

of eleven abandoned houses as well. Five houses and associated crop-land have been abandoned at Samshing where only two houses remain. And all of the more than twenty houses at Leve were abandoned before 1930 and not a single one of the scores of terraces there is now farmed. There is also a considerable number of abandoned fields at Thami Og as well as some in the other Thamicho main settlements

The immediate cause of abandonment can be determined in some cases, especially for those areas that were cultivated as recently as 1930. Diverse factors were involved. At Samshing and Samde emigration and the death of childless couples were factors. In Phurtse some terraces were also abandoned by families who emigrated to Darjeeling. Some fields abandoned near Thami Teng in the early years of the century are said to have been neglected because they had been producing poor crops. Terraces near Kenzuma in the Dudh Kosi valley were abandoned by Nauje settlers, it is said, because of repeated crop losses due to the depredations of langur monkeys more than half a century ago. Problems with Himalayan tahr were a factor in the gradual abandonment of crop production at Tashilung in the lower Bhote Kosi valley near Nauje over the past fifty years. Tahr were also a factor in some families' decisions to give up farming at nearby Nyeshe.[24]

The reasons for the abandonment of terraces before 1930 are harder to evaluate. The abandonment of the settlement of Leve, situated only a few minutes' walk from the major villages of the Bhote Kosi valley, for example, remains somewhat mysterious. There are legends describing bad luck at the place, but few details of how the houses and terraces came to be neglected. Some traditions regarding a few of the families who abandoned the settlement, however, suggest that emigration was a factor in some cases. Two families left Leve for Rolwaling and other families simply gave up growing crops at the site and concentrated instead on their nearby fields at Thami Og and other valley locations.[25] It is conceivable that the underlying factor in all of these cases was a perception that Leve had become marginal for crop production. This would also explain why no one has taken up growing crops there since. But there is no insight into this in the oral traditions. It is possible that disease may also have played some role. When traveling through Khumbu in 1885 Hari Ram reported that there had been an outbreak of smallpox in the 1850s (Ortner 1989:208, n. 4). Again, however, there is no hint in surviving oral traditions about an epidemic in Khumbu, much less a link between this and the subsequent abandonment of any settlements.

Agricultural intensification may also have been a factor. Sacherer cites this as the explanation for old abandoned terraces in Rolwaling, which she attributes to the adoption of potato cultivation. The new high

yields possible with the new crop, she suggests, rendered cultivation of some marginal land superfluous.

There can be no doubt at all that the introduction of the potato brought about an economic revolution in Rolwaling where today one can easily observe the presence of abandoned fields in the more rocky and inaccessible high altitude areas despite the fact that the valley population has increased since the conversion from barley to potatoes. (J. Sacherer, "The Sherpas of Rolwaling: A Hundred Years of Economic Change," 1977, in Seddon 1987)

In Khumbu a similar phenomenon could well have occurred in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Even if the adoption of the potato in the region was a more gradual process than has previously been assumed and if harvests were relatively small and variable by the standards of recent decades, the new crop may still have been more productive than the other available tuber crops of that era.

The location of abandoned terraces in the Bhote Kosi valley may lend some support to an intensification hypothesis. Two kinds of sites are most common: small numbers of old, unfarmed terraces located either at the edges of current settlements or at a slight distance beyond them and more extensive, abandoned terraces in some gunsa settlements. Abandoned terraces at the edges of main villages and secondary high-altitude sites may well have been considered marginal land. The abandonment of so much gunsa land requires more detailed consideration. The degree to which fields have been carved out in the steep slopes of the lower Bhote Kosi valley for gunsa fields is unparalleled elsewhere in Khumbu. The greater historical intensity of land use in the Bhote Kosi valley may well reflect greater nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century population pressure there than in Khumbu's other valleys, which led people to cultivate even quite minor patches of relatively easily terraced land. The demand for land also would have been greater in this period because more land would have been required per household for subsistence in the time before the introduction of higher-yielding varieties of potatoes. In this era it was also more common to cultivate grain as well as potatoes and to try to harvest enough to fulfill most family grain requirements.[26] Families may thus have needed to farm up to twice the amount of land that they do today. Gunsa land would have been highly appealing in this situation due to the advantages that it offers for labor scheduling. The attempt to cultivate substantially more land in the main village could have strained family labor resources to carry out planting during the relatively brief spring planting period even if the field area

had been available. Making use of gunsa lands would have expanded the agricultural season by nearly two months. Families from Thami Og, Thami Teng, and Yulajung could have planted large amounts of land as early as the beginning of March rather than waiting until late April.

The later adoption of higher-yielding potato varieties and the ability to grow more food on less land might well have led to a consolidation process as families devoted less time and energy to farming and relied on the larger harvests now possible on their best fields in main villages and high-altitude secondary agricultural sites. Presumably the further introduction of even higher-yielding potato varieties meant that many terraces were never returned to cultivation, although some were certainly sold to new immigrants.

Agricultural Change 1930-1973

Agricultural change can be reconstructed in much more detail for eras within living memory, and far more careful cross-checking of sources is possible for the period after 1930 than for earlier eras. This oral history testimony suggests that the middle of the twentieth century was characterized by an increasing emphasis on potato cultivation. This was associated with the adoption of another variety of potato, riki rnoru (red potato). This round, red-skinned, pink-flowered potato was both better yielding and more consistent in yield than earlier Khumbu varieties had been. It was adopted throughout the region and supplanted almost all other tuber cultivation. Turnip and radish ceased to be grown as field crops, kyuma was grown on a smaller scale than it had been, and other potato varieties began to disappear from the region (maps 15a and 15b). With the adoption of the red potato thus began the era of potato-dominated Khumbu agriculture so familiar to foreign visitors since 1950. There were also other less spectacular changes. The area in crops expanded on a small scale in some areas such as Phurtse, Nauje and lower Pangboche where terraces were constructed on previously unfarmed slopes.[27] Draft plowing was also more adopted for grain farming during this period, especially after the 1950s.

The Introduction of the Red Potato (Riki Moru)

There are several accounts of the introduction of the red potato. These may reflect several different introductions to different parts of Khumbu over the course of two decades. According to one Khumjung account the red potato was originally brought to Pharak from Lazhen (a valley in Sikkim) by Karke Tikpe and Ang Pasang, who planted it in Tsermading

(half a day's walk south of Nauje) more than sixty years ago. A second Khumjung resident recalls that Ou Sungnyu of Kunde first brought the red potato to Khumjung and Kunde close to fifty-five years ago. One Thami Teng resident who was seventy-seven years old in 1985 recalled getting his first red potato seed directly from Pharak when he was about twenty-four years old (ca. 1932). He also remembers hearing that Pharak Sherpas had gotten the variety from Lazhen. This Thamicho man recalls that from his first small pot of seed potatoes he harvested a single basket load and from this small beginning (and a few potatoes brought from Pharak by other Thamicho Sherpas) the new variety spread throughout the Bhote Kosi valley. The red potato may have been introduced to eastern Khumbu slightly later.

When moru first appeared it had a very high yield, comparable in some people's memories to that of the yellow potato when it was first grown in the 1970s. In good years some large landholding families harvested so many red potatoes that they were unable to sell their surplus even at a quarter-rupee per eleven kilograms (versus a 1991 price of fifty rupees/11kg) and had to throw many tubers out even after they had used all they could as livestock fodder. The new crop was susceptible to frost and to blight, but represented a much more dependable food source than had earlier potato varieties.

The red potato did not totally supplant kyuma in the region, which was still cultivated on a small scale in main villages until the 1960s and even more recently in some high-altitude settlements. Many Sherpas maintain that kyuma was abandoned not simply because a higher-yielding variety became available, but also because its yields began to decline. This is widely believed to have been related to the introduction of the red potato. Many people believe that the introduction of a new potato variety into a settlement adversely affects the characteristics of varieties already being grown there. Yields decline because plants feel offended or neglected by the attention being transferred to the new variety. The resulting poor performance may hasten the old variety's abandonment. The same explanation is also given to account for the later decline of red potato yields and the recent perceived decline of yellow potato yields.

The red potato was not the only potato introduced between 1930 and 1975, but it was the only variety that was widely adopted. Some families experimented briefly with linke , but this white, watery variety developed a reputation for causing stomach problems which led to its total rejection in Khumbu. The brown potato (mukpu ), which is regarded so highly in the Bhote Kosi valley, may also have been introduced during this period. According to some poeple it was originally obtained from Pharak Sherpas.

Map 15a.

Agricultural Change: Bhote Kosi Valley Agriculture, circa 1920

Technological Change

Prior to the 1950s plowing in Khumbu was usually done by teams of men rather than by draft animals. It is unclear why this practice persisted as long as it did throughout the region. Draft plowing was the usual prac-

Map 15b.

Agricultural Change: Bhote Kosi Valley Agriculture, 1987

tice in Tibet, and indeed the dimzo raised in Khumbu for sale there were primarily in demand as plow and pack animals. Yak are also used as plow animals in Tibet and today some Sherpas plow behind yak. Yet earlier in the century neither yak nor zopkio seem to have been widely used in this way in Khumbu. It was only during the 1950s that draft

plowing began to supplant plowing by human teams throughout the region. Men still pulled plows in Phurtse until only a few years ago. In Phurtse the increasing adoption of draft traction was the cause for some tension within the community. Men who had made good wages by pulling plows resented the loss of this opportunity. This had been the best paying day labor in the area, for each of the three or four men pulling a plow was paid double to triple the normal wage for agricultural day labor and was given better quality food and beer than normal laborers. Some families who began hiring yak- and zopkio-pulled plow teams to prepare their buckwheat fields are said to have been told by men who formerly had plowed their fields that they could have the livestock do their weeding and harvesting as well, for their families would not work for them again.

The adoption of draft plowing may still be underway in Khumbu today. During the 1980s a few families in Nauje and in Khumjung began having large potato terraces plowed, breaking with the custom of only plowing grain fields. This was judged to be cheaper than hiring agricultural laborers to perform the same work. It is not yet, however, a very widespread practice. Virtually all families continue to rely on either reciprocal labor arrangements or hired labor to dig and prepare their potato fields with hoes. A cultural factor may also be involved, for some people feel that digging potato fields gives more energy to those fields than plowing does, producing better crops. This impression could conceivably be related to a difference in the depth to which the soil is worked. The Khumbu scratch plow probably does not work the soil as deeply as hoe digging does.[28]

Post-1960 Agricultural Changes

In the past thirty years there have been a number of changes in Khumbu agriculture. These include changes in values that have affected community agricultural management practices, the introduction of additional new potato varieties, the decline of buckwheat production, an increase in the attention given to growing fodder crops, and continuing experimentation with new techniques and crops.

Blight-prevention Practices

During the 1960s the enforcement of regulations aimed at preventing blight declined across much of Khumbu except Phurtse, Pangboche, and Dingboche. In Nauje few of the prohibitions had been enforced with any stringency for some years and even in the 1960s the only bans carefully enforced were the exclusion of livestock from the village after Dumje

and the prohibition on bringing freshly cut wood into the village after the fourth day of the sixth month, Dawa Tukpa, two weeks later. The ban on bringing freshly cut wood into the village during the time of maximum blight danger ceased to be enforced around 1965 and after that the Nauje nawa only enforced the livestock-control measures. During the late 1960s and early 1970s many blight-protection provisions were also abandoned in Thamicho, Khumjung, and Kunde. By the mid-1970s only Phurtse, Pangboche, and Dingboche enforced prohibitions against bringing in freshly cut wood after the fourth of Dawa Tukpa. All settlements, however, continued to enforce the mid-summer bans on grazing near the villages.

The decline in the enforcement of some blight-related rules in several villages appears to go back to well before 1960 and reflects changing beliefs. But the striking decrease in enforcement of restrictions on freshly cut wood in the late 1960s and early 1970s in Nauje, Khumjung, and Kunde may be related to changes in local resource management after 1965. The implementation of new forest regulations by a government office in Nauje led to the abandonment of local enforcement of tree-felling rules in those three villages. Perhaps it was decided that all other forest-related controls had also been made unenforceable by the government's announcement that it would be responsible for forest management.

The Introduction and Diffusion of the Yellow Potato (Riki Seru)

In the middle of the 1970s yet another new potato variety was separately introduced to Khumbu by two men from different parts of the region who encountered it in very different parts of the Himalaya. Both had recognized the variety as something new, a potato of a different color and texture which had a reasonably good taste and produced a high yield of large tubers. Both brought back a few seed potatoes to grow at home, one planting these in Thamicho and one in Khumjung. Following these introductions the tuber became the most important variety throughout the main villages of Khumbu within ten years and diffused from Khumbu to Pharak, Shorung, Salpa, and even the Rai regions of the Hinku and Hongu Khola and the lower Dudh Kosi.

The yellow potato was brought to Khumjung by Pemba Tenzing about 1976.[29] He encountered the new variety at Singh Gompa north of Kathmandu on the trail to Langtang National Park. While employed by a tourist trekking group he made an overnight stop at the monastery and met an old Tamang friend who was then working in the monastery kitchen. His friend served him some boiled potatoes which Pemba

Tenzing noticed were unusually large in size. He asked if he could have half a load (15-20kg) of them to take back to plant in Khumbu.[30] The Tamang was unwilling to part with that many, but did give him five potatoes. From the five potatoes that Pemba Tenzing and his wife planted they harvested five tins (ca. 50kg) of the yellow-tinted, slightly watery, large, oval tubers. From these few potatoes, he notes, the yellow potato spread all over Khumbu.

That they did spread throughout Khumbu and far beyond in remarkably little time had a good deal to do with Pemba Tenzing's neighbors, Konchok Chombi and his wife Ang Puli. Konchok Chombi and Ang Puli obtained two yellow potatoes from Pemba Tenzing's wife. She cut eighteen eyes (mik ) from these and planted them, harvesting nearly a tin (11kg) of potatoes. These were planted the next spring and yielded four loads. During the next few years they obtained successively greater amounts of seed potato and before long were able to convert almost their entire Khumjung production to the new variety. Soon they were harvesting more than 200 loads per year.

Konchok Chombi realized the importance of the new variety and spread the word widely about the discovery. Equally as important, he was able to provide seed potatoes for others to buy and introduce into their own fields and villages. By Khumbu standards Konchok Chombi is a large landowner with four large fields at Khumjung which can produce harvests of up to 400 loads of yellow potatoes in the best years, far above his household requirements. Not only could he provide seed potatoes, but in order to meet the widest possible demand and diffuse the new variety as rapidly as possible he limited purchases to a small amount of seed potatoes per customer. He would sell no more than three tins (33kg) to any one family, enough for them to harvest sufficient seed potatoes the following year to plant much of their fields in the variety. Beyond this he even promoted the new potato in other regions, sending girls of seed potatoes to the Sherpa villages of Golila, Gepchua, Mure, and Tingla west of Shorung, to Chaunrikharka in Pharak, and to Sher-pas in the Katanga and Kulung regions. Villagers from Pharak began to seek him out at home for the new tuber. Within a few years the potato became known in much of the region as "Au (uncle, a respectful term of address) Chombi's potato." Pemba Tenzing's discovery of the variety has been nearly totally forgotten.[31]

Also largely unknown is the fact that there were not one but two introductions of the yellow potato to Khumbu. Outside of Thamicho most Sherpas are totally unaware of the separate introduction of the variety to Pare and Yulajung. About 1973 Dorje Tingda, a Thamicho man who has houses in Pare and Yulajung, discovered a potato in Dar-jeeling which is now considered to be identical to the Khumjung tuber.

He brought back a small quantity of potatoes that he had first noticed while having lunch in a tea shop near Darjeeling while guiding tourists on a local pony trail. It is said that for three or four years he kept knowledge of the new variety to himself because he was worried that if other families also began producing the new, yellow variety it might affect the business he was then doing selling his crop to the Japanese-operated Everest View Hotel near Nauje. According to some Thamicho residents he only began selling villagers potatoes after three local Sherpa panchayat officials asked him to sell them a few. One of these officials, a Yulajung Sherpa, noted that from the single tin of potatoes he obtained he harvested four large loads (more than 160kg) the first year. He had thought that this was an unparalleled harvest until he learned that one of the other officials had harvested five loads from his single tin. After that, he remarked, the new potato spread rapidly through Thamicho.

The pace of the diffusion of the yellow potato through Khumbu can be roughly charted. Thamicho acquired the variety mainly through its introduction to Pare, but it was not until the early 1980s that there was very wide diffusion of the tuber because of the difficulties in acquiring seed potatoes.[32] By 1981 the potato was becoming well established in Nauje as well as Khumjung and Kunde. In these places it was grown on an approximately equal basis with the red potato by 1985, and by 1987 dominated crop growing. In eastern Khumbu the yellow potato became established slightly later. It was first planted in Phurtse in 1981, but many families there did not begin planting it until 1983 or 1984. It has, however, become the major variety grown there during the past few years. The yellow potato was first planted at Dingboche in 1982 and may have been tried at Pangboche a few years earlier.

The rapidity with which the yellow potato was adopted and at which it supplanted the red potato in the main villages reflects Sherpas' interest in experimentation with new varieties and with adopting high-yielding varieties. In this case the degree of interest in greater harvests outweighed a number of early reservations that many people had about the variety. A considerable number of people initially disliked its taste and many farmers initially refused to grow it. It was also noticed very early on that the variety had a different growing pace and different characteristics than the red potato, and some farmers were concerned that this would diminish the yield of intercropped radish. Some families for whom radish production for use as fodder was important were reluctant to cultivate the new variety as a result. There were also questions about its performance at higher altitudes. It was felt that the yellow potato's longer growing season put it at greater risk than the red potato in the short summer season of the high-altitude settlements. Some people who experimented with it in the Dudh Kosi and Imja Khola valleys

at altitudes above 4,000 meters also found that the tuber seemed to become still more watery when grown at that altitude. This reputation for poor taste at high altitude led a number of families in eastern Khumbu to decide not to grow the variety at sites above the main villages.

Many of these early evaluations, however, were modified within a few years as the process of testing and evaluating the yellow potato continued. Families experimented with the variety at different sites and people noted with interest the crop experiments of the pioneer growers in each locality. Word of good harvests spread quickly. Farmers who said in 1984 that they would never plant the yellow potato were planting it by 1987. The reservations about its taste became less pronounced, although the red potato continued to be proclaimed the finest-tasting potato in Khumbu.[33] It even began to be grown more widely in high-altitude settlements. By 1987 the variety was being planted by many families at Dingboche and also by several families at Na despite earlier reports that yellow potatoes that had been planted there had had poor taste. By 1987 it had also become the major variety planted at Tarnga. The yellow potato, however, has still not been universally accepted as fit for high-altitude planting. Some people refuse to plant it at Dingboche and in the upper Dudh Kosi and others are reluctant to plant it at Bhote Kosi valley sites higher than Tarnga. The increased wateriness of the tuber at these altitudes is still the factor most often noted as the main factor in this decision.

The Introduction of Other New Potato Varieties

Following the introduction of the yellow potato at least two and possibly three more varieties have been introduced to Khumbu by Sherpas who encountered them elsewhere. The most important across Khumbu is development potato (riki bikasi ), which is said to have been introduced about 1981 from Phaphlu in Shorung by a Nauje man who brought back some from the agricultural extension office there.[34] Thus far the development potato has been grown primarily in lower Khumbu, especially in Nauje, Khumjung, Kunde, Thami Og and Thami Teng. In the Bhote Kosi valley it has been experimented with as high as Tarnga. Very little was being grown in 1987 in Yulajung (although families there have been experimenting with it for at least two years), but it is being grown fairly widely in Thami Og and Thami Teng. The adoption of the variety was slowed down in Yulajung by concerns over its storage qualities and in eastern Khumbu both by doubts about its hardiness at higher altitudes given its long growing season and by a lack of seed potatoes.[35] There

have been reservations also about its taste and its high degree of wateriness. Some people suspect it causes stomach problems and others are convinced that it is lower in food energy than other potato varieties. But the yields of development potatoes are usually so outstanding even in comparison to the yellow potato that the new variety continues to be experimented with by many farmers and to be adopted increasingly widely. By the late 1980s there were fewer reservations about both its altitudinal fitness and taste, although many people still consider it far inferior in taste to the red potato, the yellow potato, and kyuma.

It is possible that the brown potato (riki mukpu ) was also introduced in this period, although some people put the date of its introduction earlier. The brown potato is a round, dark-skinned variety of uncertain origins, which some Sherpas maintain was introduced in the late 1970s from Pharak.[36] It has developed a reputation for yielding well at high altitudes and is much sought after by people who want to experiment with a few plants in their fields. The secondary high-altitude agricultural site of Goma in the upper Bhote Kosi valley is very well known as a center of brown-potato cultivation, but thus far the variety is little grown outside of the upper Bhote Kosi valley.

The latest addition to the Khumbu potato repertoire was introduced by Nauje families (including Sonam Hishi's family) from Pharak in 1987. It has no commonly accepted name. Sonata Hishi's wife Chin Dikki is calling it, with much amusement, long tail (ngamaringbu ) after a hairlike protrusion from the base of the tuber.

The Decline of Buckwheat Cultivation

Until the 1970s substantial amounts of buckwheat were being grown in all Khumbu villages other than Nauje.[37] In Khumjung, Kunde, Pangboche, and Phurtse buckwheat continues to be grown on a great deal of land and in Phurtse and Pangboche it is planted on nearly 50 percent of the cropland. Formerly considerable buckwheat was grown in the villages of the Bhote Kosi valley as well as in some of the gunsa and at Tarnga. But buckwheat has long been less emphasized there than in the other buckwheat-growing areas. According to elderly residents even in the early decades of the century buckwheat was grown on as little as a quarter of the land in Thami Og. During the past ten years interest in planting buckwheat in the Thamicho villages has plummeted. In 1986 it was being grown in Thami Teng in only three fields and the following year was only cultivated in three small patches. In 1987 only a single, small field was planted in Yulajung and no buckwheat whatsoever was grown in Thami Og. The Bhote Kosi valley has become monocropped with potatoes from the gunsa to the high-altitude herding settlements.

There may be several factors in this increased emphasis on potato cultivation in the Bhote Kosi valley. One may be population pressure and a response to it by intensifying production. As food demand in the Bhote Kosi valley increased during the twentieth century it might be expected that potato production would be further emphasized, for it produces much more food per hectare than any other Khumbu crop and can form the bulk of a household's diet if necessary. For at least half a century families with little land have tended to put their limited land to potatoes and to grow less buckwheat. One of Khumbu's oldest residents, a man of Khumjung, noted that when he was young if a family had a good deal of land it would plant half in kyuma and half in buckwheat and rotate them annually, but that if it was poor it would primarily plant potatoes. A concern with intensification probably also led families in Nauje, where land is in very short supply relative to the size of the population, to emphasize potato monoculture. There grain cultivation was abandoned very early in the century.

Yet there remain some questions about the role of response to population pressure in the conversion of land from buckwheat to potatoes. It is unclear how great recent population growth has been in the Bhote Kosi valley and to what degree fragmentation has affected land ownings per household. It does not seem likely that land shortages there are significantly greater than in eastern Khumbu where buckwheat has not been abandoned. Even if the average size of household land holding has declined valleywide there are still problems with a simple intensification explanation, for not all families are equally land-poor, and there is no doubt that many Thamicho families do own amounts of land which are substantial by Khumbu standards. That even these households have chosen to specialize in potato production suggests that factors other than population growth are involved in the current monoculture of potatoes in the valley.

Commercialization might be a factor, although this is difficult to substantiate given the lack of pertinent household and land data. Thamicho has long exported small amounts of dried potatoes to Tibet and since the early 1970s it has played an increasingly important role in the small-scale regional exchange of potatoes within Khumbu itself. Many Nauje families have depended for generations on purchasing some potatoes to augment their own production. Before the mid-1970s much of the Nauje demand was met by Khumjung production. During the mid-1970s more attention was turned towards the Bhote Kosi valley when Khumjung suffered a series of disastrous harvests. During the last years before the widespread adoption of the yellow potato Bhote Kosi valley surplus potato production became important not only for Nauje families but also for many Khumjung and Kunde households. Demand was so high that

tension broke out between Nauje villagers and those of Khumjung because some Khumjung residents were intercepting Thamicho farmers on their way to the Saturday market at Nauje and buying out their entire supply of potatoes.[38]

The adoption of the yellow potato eased the shortage of potatoes in Khumbu, but demand for tubers continued to increase as a result of growth in the numbers of Nepali residents in Nauje and dramatic increases in the scale of tourism. Tourists consume large quantities of locally grown potatoes that are an important component of both the food offered by local lodges and that cooked by commercial camping tours. Potatoes are sold to families, lodgekeepers, and trekking groups at the Saturday market at Nauje as well as continuing to be bartered in direct family-to-family exchanges. Some Nauje households, for example, make deals with Thamicho farmers for potatoes months before the harvest, offering cash, tea, kerosene, and other commodities bought at bulk prices at the Nauje market or in Kathmandu.

The possible relationship between greater opportunities to sell potatoes locally and increased Thamicho emphasis on their production requires further study. As of now I cannot evaluate how common it is for Thamicho farmers to sell surplus potatoes or the role that interest in producing a surplus plays in crop decisions. When I attempted to pursue this line of investigation in 1987 I found that Thamicho farmers unanimously denied that an interest in selling potatoes had anything to do with their decisions to discontinue the cultivation of buckwheat. They also did not cite land shortage as a factor. This does not mean that commercial motives and interest in intensification are not factors in land-use decisions, for certainly an interest in higher yields has driven the recent widespread adoption in Thamicho of the yellow potato and the development potato, and some families must make substantial income from the sale of potatoes. But it does suggest that these were not the most immediate reasons for the relatively rapid and extensive recent decline in buckwheat growing.

According to Thamicho farmers the decline of buckwheat in their region was caused by the increase in the number of crossbreeds herded in the valley and the breakdown of local pastoral managment regulation. This has made it increasingly risky to cultivate buckwheat. Yak and zopkio have always been considered threats to buckwheat crops and urang zopkio especially are considered very apt at slipping down valley and getting into fields. The great increase in the 1980s in the number of crossbreeds kept by Thamicho villagers magnified this risk. Thamicho people complain that whereas yak and nak seem content to graze in the high pastures of the upper valleys in late summer that some urang zopkio move down valley during the night and break into buckwheat

fields. By the time the damage is discovered in the morning entire fields can be ruined. This risk is further increased in late August and early September when many Thamicho herders take pack stock to Nauje to meet mountaineering expeditions. According to local regulations they are only allowed to spend a single night in the zones closed to grazing around the main villages as they move their stock through to Nauje. But many herders abuse this custom and keep their stock based in the villages for days. These violations and the nawa's inability to control them have not only seriously threatened buckwheat crops but have also been an important factor in undermining the effectiveness of the entire system of herding regulation in the Bhote Kosi valley during the mid-1980s.

Fodder Crop Production

Another trend during the past two decades has been an increase in fodder-crop and hay production. This has been especially marked in the Bhote Kosi valley and in Nauje. In Nauje more terraces are being planted to fodder crops and a few fields in Thami Og and Khumjung have also been planted in fodder crops recently rather than in food crops. Many new hayfields have also been established, especially in the Bhote Kosi valley. Some were created from pastureland in the upper valley, whereas others in the main villages were converted from cropland. Large numbers of such converted fields can be seen at Yulajung where they represent a major hay-growing resource for settlement families. There are also examples in Thami Teng and Thami Og as well as in Tarnga, Marulung, and some lesser settlements.[39] The interest in producing more hay and fodder in Thamicho probably reflects both the end of winter herding in Tibet and the recent decline of the nawa-enforced regulations that formerly protected some winter pasture and areas where wild grass was collected for hay from year-round grazing.