Preferred Citation: Doumani, Beshara. Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft896nb5pc/

| Rediscovering PalestineMerchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900Beshara DoumaniUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · London© 1995 The Regents of the University of California |

To my parents,

Hanna Doumani and Mounifa Barakat

and to my lifelong friend,

Halim

Preferred Citation: Doumani, Beshara. Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1995 1995. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft896nb5pc/

To my parents,

Hanna Doumani and Mounifa Barakat

and to my lifelong friend,

Halim

Preface

This book attempts to write the inhabitants of Palestine into history. Using the documents they generated during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, I have tried to make their society and its inner workings come alive by listening to their voices and by gazing at the world through their eyes. This book also seeks to make a small contribution to a rethinking of Ottoman history by foregrounding the dynamics of provincial life in the vast Ottoman interior, especially the role of merchants and peasants in the shaping of urban-rural relations.

Considering that the historiography of Palestine is dominated by nationalist discourses on both sides of the Palestinian-Israeli divide, and that these discourses are built on the premise of a sharp discontinuity from the past caused by outside intervention, there is no shortage of assumptions to be revised and new issues to introduce. This book calls for a rediscovery of Ottoman Palestine by drawing attention to long-term processes and by highlighting the agency of the inhabitants in the molding of their own history.

The first, formative period of research, 1986–1988, was made possible by an International Doctoral Research Fellowship granted by the Joint Committee on the Near and Middle East of the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies, with funds provided by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. The University of Pennsylvania Research Foundation funded further forays into the archives in 1991. Much of the writing was done in 1993 while I was on leave from the University of Pennsylvania School of Arts and Sciences.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to the employees of the Nablus Islamic Court who shared their crowded office with me, for there was no separate room for researchers. Nazih al-Sayih’s calm authority, humor, and sensitivity made the court feel like home and kept us focused despite the all-too-frequent distractions of nearby gunfire and the biting wafts of tear gas that seeped through the windows. Jawwad Imran, always with a smile in his heart, shared his desk with me six hours a day, six days a week, for more than two and a half years. All answered my never-ending questions and posed a few of their own.

A network of people helped me gain access to private family papers. The late Ihsan Nimr, whenever he was asked to share his extensive collection of private family papers, always referred researchers to his book instead. Husam al-Sharif, in addition to kindling my interest in soap factories, arranged for me to photocopy this collection, thus making it publicly accessible for the first time. When Lubna Abd al-Hadi showed me a loosely bound collection of old papers, neither she nor I could have imagined that I would spend years examining what turned out to be the remarkably rich records of the Nablus Advisory Council (majlis al-shura). Hajj Khalil Atireh, Adala Atireh, Saba Arafat, and Naseer Arafat are but a few of the many people who made it possible for me to tap into the collective memory of Nabulsis by facilitating my access to people, places, and papers.

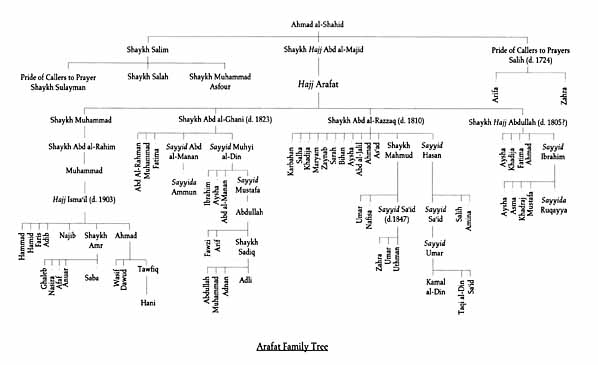

Judith Tucker introduced me to the world of court records and the field of social history. As a graduate student I also learned from (and was humbled by) the rigorous scholarly work of Hanna Batatu, and I sharpened my theoretical tools with the help of Hisham Sharabi. Notes on an earlier version of the manuscript by Roger Owen, Edmund Burke III, and Ken Cuno considerably strengthened the final product, as did the valuable comments of Leila Fawaz, Zachary Lockman, Abdul-Karim Rafeq, Linda Schilcher, Bruce Masters, David Ludden, Lee Cassanelli, Salim Tamari, and Joe Stork. Andrew Todd prepared the city and regional maps of Jabal Nablus, and Bridget O’Rourke designed the family tree (Plate 5). That this book has seen the light of day is due largely to the love, patience, and support of Ismat Atireh.

Abbreviations

- AAS

- African and Asian Studies (Jerusalem)

- IJMES

- International Journal of Middle East Studies

- IJTS

- International Journal of Turkish Studies

- JESHO

- Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient

- JICR

- Jerusalem Islamic Court Records

- JPOS

- Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society

- JPS

- Journal of Palestine Studies

- MES

- Middle Eastern Studies

- NICR

- Nablus Islamic Court Records

- NIMR

- Ihsan Nimr, Tarikh Jabal Nablus wa al-Balqa,(4 vols.; Nablus, 1936–1961).

- NMSR

- Nablus majlis al-shura Records

Note on Translation and Transliteration

I wrote this book in a language that I hoped would prove both accessible and interesting to first-time students of the Middle East and that would impart a live and intimate portrait of the people of Palestine during the Ottoman period. In translating the numerous documents which carry their voices, I tried to avoid the technical jargon so common in Ottoman Studies. Whenever possible, I used English instead of Arabic or Turkish terms. When Arabic and Arabized words do appear (usually in parentheses), I transliterated them according to the system of the International Journal of Middle East Studies. All diacritical marks were omitted except for the ayn (‘) and hamza (’), and these were used only when they occur in the middle of a word or name. Definitions of Arabic terms are provided in the text the first time they are used. A glossary of the most frequently used terms can be found in the back of the book.

Maps

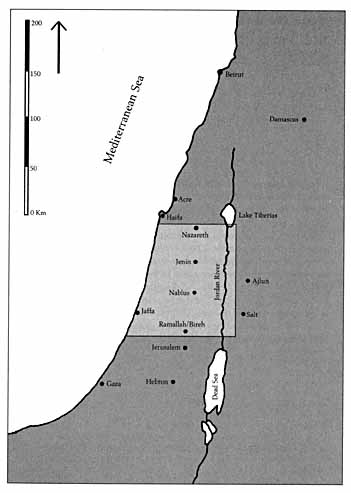

Map 1. Southern Syria

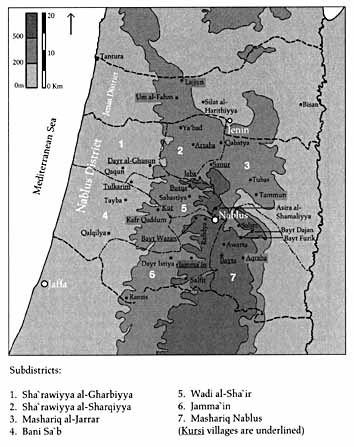

Map 2. Jabal Nablus, circa 1850

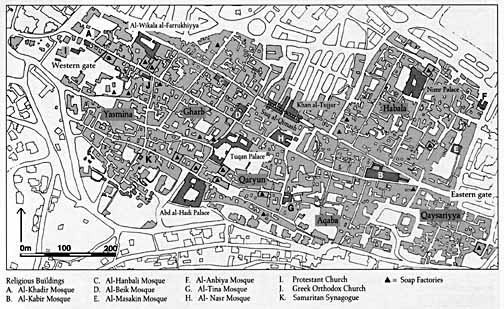

Map 3. Nablus Old City, showing the positions of key buildings in the late nineteenth century (base map, Nablus Principality, 1987)

Introduction

Palestine and the Ottoman Interior

During the eighteenth and most of the nineteenth centuries, the city of Nablus was Palestine’s principal trade and manufacturing center.[1] It also anchored dozens of villages located in the middle of the hill regions which stretched north–south from the Galilee to Hebron and which were home to the largest and most stable peasant settlements in Palestine since ancient times. This study unpacks the social history of Nabulsi merchants and peasants by exploring the relationship among culture, politics, and trade. It investigates how merchants built and reproduced local and regional networks, organized agricultural production for overseas trade, and gained access to political office and to the major means of agricultural and industrial production (land and soap factories). It also examines the ways in which they competed with foreign and regional merchants based in the coastal cities, as well as their discourse with Ottoman officials who were keen on securing the state’s share of the rural surplus.

Peasants left far fewer clues for the historian to assemble than merchants did. This study attempts to discern their role in the construction of urban-rural commercial networks and to outline how growing urban domination over the rural sphere complicated the peasants’ relations with each other and with their rural chiefs. It also traces the coming of age of a middle peasantry and details their efforts to reproduce urban economic and cultural practices on the village level. Finally, peasant initiatives, ranging from petitions to violent confrontations, are mined for clues about how they defined their identity, understood their connection to the land, and formulated their notions of justice and political authority.

I undertook this study with two goals in mind: first, to contribute to a bottom-up view of Ottoman history by investigating the ways in which urban-rural dynamics in a provincial setting appropriated and gave meaning to the larger forces of Ottoman rule and European economic expansion; and second, to invite a rethinking of the modern history of Palestine by writing its inhabitants into the historical narrative, a task largely neglected by the predominantly nationalist (re)constructions of its Ottoman past.

| • | • | • |

Toward a History of Provincial Life in the Ottoman Interior

As a single unit, Nablus and its hinterland constituted a discrete region known for centuries as Jabal Nablus.[2] Scores of roughly similar regions filled the interior of the vast and multiethnic Ottoman Empire and surrounded each of its few large international trading cities like a sea around an island. Home to the majority of Ottoman subjects, these discrete regions were located at one and the same time at the material core and the political periphery of the Ottoman world. The opinions of their inhabitants did not carry much weight in determining the political course of the central government in Istanbul, but their combined human resources and productive capacity were absolutely crucial to the empire’s tax base and to the provisioning of its metropolitan centers and military forces. An in-depth look at the changing political economy of these provincial regions can provide a valuable and fresh perspective on the deep undercurrents of change in the Ottoman domains.

The need for such a perspective has been made clear by the two dominant trends in the growing field of Ottoman Studies. The first has relied mostly on mining the central Ottoman archives and has used the state as the key unit of analysis. The invaluable research in these archives has demonstrated the dynamic character of the Ottoman Empire and has shown that its remarkable longevity was due largely to the energetic, flexible, and thoroughly pragmatic policies of its central administration.[3] The second (more recent) trend, has focused on the capital cities of the provinces—such as Cairo, Damascus, Aleppo, or Beirut—as the point of departure. Using a wide range of sources, including records of the local Islamic courts, these studies have brought to the fore the realities of daily life in large urban settings and have elucidated the diverse historical trajectories possible under the umbrella of Ottoman rule.[4]

Both vantage points have also made painfully clear that the survival of both the Ottoman Empire and its international trading cities was predicated, first and foremost, on their ability to gain access to and control the agricultural surplus of the peasants and the trading activities of the merchants in the interior. Indeed, it is around these two key issues, access and control, that much of the debate on the history of the Ottoman Empire revolves. Precisely because the discrete building blocks of the Ottoman world, interior market towns and their hinterlands, were not passive spectators in these struggles for access and control, the frontiers of research must be pushed to their doorsteps and their experiences must be integrated into the larger discourse of Ottoman history.

When it comes to the modern period, this discourse has been dominated by a single overarching narrative: the piecemeal incorporation or integration of the Ottoman Empire into the European economic and political orbits. This narrative is a central one because it deals directly with the problematics of capitalism, imperialism, and colonialism and because it has implications for current debates on development strategies, international relations, regional conflicts, state formation, and the social bases of nationalist movements. A variety of approaches have been used to frame this narrative,[5] but the same underlying set of economic and political issues continues to be hotly debated: the commercialization of agriculture and the patterns of trade with Europe; the impact of European machine-produced imports on local manufacturing; the growth of coastal trade cities and the rise of minority merchant communities which served as go-betweens; the commoditization of land and the emergence of a large landowning class; the Ottoman government’s program of reforms; and the rise of nationalist movements, to name but a few.[6]

In discussions of these key issues the Ottoman Empire was, until fairly recently, usually portrayed as a stagnant, peripheral, and passive spectator in the process of integration. The decline thesis, as it has come to be called, has been persuasively challenged since the early 1970s,[7] but the very thrust of the integration narrative, regardless of the theoretical approach used, tends to relegate the interior regions of the Ottoman Empire, such as Jabal Nablus, to the status of a periphery’s periphery. Hence, despite the rapidly growing number of studies, little is known about provincial life, albeit with some important exceptions.[8]

In the case of Palestine it has long been assumed, for example, that transformations in agrarian relations usually associated with so-called modernization did not begin until the first wave of European Jewish immigration in 1882. According to Gabriel Baer, “Arab agriculture did not change its traditional character throughout the nineteenth century. German and Jewish settlers introduced some innovations, but subsistence farming continued to be the predominant type of agriculture in the country, and the growing of cash crops was rare.”[9]

Baer seems to have confused traditional methods of farming with subsistence agriculture. Methods and technology remained largely unchanged, it is true, but they were eminently suited to the thin topsoil and rocky ground of the hill regions, the heartland of Palestinian peasantry. Indeed, it was with these traditional means that Palestine, as later shown in a pioneering study by Alexander Schölch, produced large agricultural surpluses and was integrated into the world capitalist economy as an exporter of wheat, barley, sesame, olive oil, soap, and cotton during the 1856–1882 period.[10] In addition, through a detailed study of Western sources, especially consular reports on imports and exports through the ports of Jaffa, Acre, and Haifa, Schölch showed that exports not only closely shadowed shifting European demand but also exceeded imports of European machine-manufactured goods, which meant that Palestine helped the rest of Greater Syria minimize its overall negative balance of trade with Europe.[11]

Schölch chose the Crimean War as a starting point because of the strong demand it generated for grains and because of the new political environment created by Ottoman reforms (Tanzimat).[12] But the qualitative leap in trade with Europe between 1856 and 1882, it seems to me, could only have taken place given an already commercialized agricultural sector, a monetized economy, an integrated peasantry, and a group of investors willing to sink large amounts of capital into the production of cash crops. Pushing the process of integration further back in time would help explain the massive and quick “response” of Palestinian peasants and merchants to the increase in European demand and would bring the experience of Palestine into line with the rest of the Ottoman domains. More important, what is now called the Middle East was not a stranger to commercial agriculture, protoindustrial production, and sophisticated credit relations and commercial networks.[13] The same has been shown for other regions, especially for South Asia.[14] In other words, many of the institutions and practices assumed to be the products of an externally imposed capitalist transformation existed before European hegemony and may in fact have helped pave the way for both European economic expansion and Ottoman government reforms. It is critical, therefore, to examine the local contexts in which the processes of Ottoman reform and European expansion played themselves out and to explore how these processes were perceived and shaped by the inhabitants of the Ottoman interior.

Because each market town and its hinterland had its own deeply rooted and locally specific social formation and cultural identity, the question becomes: how to conceptualize the relationship between this bewildering diversity of largely semiautonomous regions and the central government in Istanbul? A complicating factor is that Ottoman administrators, long faced with the same dilemma, neither set out to nor could impose a uniform set of policies, at least not until the 1860s. Rather, different and sometimes contradictory fiscal and administrative arrangements were introduced over the centuries, and they often coexisted and overlapped for long periods of time. In addition, the implementation of government policies was usually channeled indirectly through local elites, as a result of which the policies were constantly reformulated and redefined.

Ever since the publication in 1968 of Albert Hourani’s article on the “politics of notables,”[15] historians of the Ottoman provinces in general and of Greater Syria in particular have had access to an insightful framework which explains how native elites mediated between the local inhabitants and the central government authorities.[16] Yet to emerge is an equally persuasive framework which situates the political role of notables within the material, social, and cultural contexts in which they operated, on the one hand, and which allows an agency for those outside public office, particularly merchants and peasants, in the molding of their own history, on the other.

In Greater Syria during most of the Ottoman period, local and regional commerce was every bit as important, if not more so in terms of daily life, as trade with Europe.[17] The merchants of the interior dominated commercial, social, and cultural networks that, so to speak, were linchpins which connected the peasants who produced agricultural commodities with the artisans who processed them and with the ruling families who facilitated the appropriation and movement of goods.[18] These networks also connected the interior regions to each other and, in the process, made it possible for European businessmen and the Ottoman government to gain access to the surplus of these regions. Access and control depended, in other words, on making use of the interior merchants’ knowledge of the productive relations on the village level, their credit advances to peasants, their organization of local production for overseas exports, their management of regional markets and trade routes, and their domination of local retail venues and small-scale manufacturing. Merchants of the interior, therefore, occupied a crucial mediating position that could be seen as the underlying basis or economic and cultural counterpart to Hourani’s “politics of notables.” This book pays special attention to merchant life and to the changing relations between merchants, peasants, and the central Ottoman government.

| • | • | • |

Rethinking Ottoman Palestine

The contours of inquiry into the modern history of Palestine have been and continue to be shaped by two factors that set this region apart from most of the other Ottoman domains: its symbolic and religious significance to Muslims, Christians, and Jews all over the world and the century-long Palestinian-Israeli conflict, an intense political drama that pits two nationalist forces in a struggle over the same land.[19] The combination of these factors has resulted in a voluminous but highly skewed output of historical literature. On the one hand, thousands of books and articles have focused high-powered beams on particular periods, subjects, and themes deemed worthy of study. On the other hand, entire centuries, whole social groups, and a wide range of fundamental issues remain obscure.

The dominant image in the West of Palestine as the Holy Land has concentrated the output of historical texts on the Biblical, Crusader, and modern periods (especially after the British occupation in 1917), because they were perceived as directly linked to European history. Meanwhile, hundreds of years of Arab/Muslim rule have largely been ignored.[20] As the site of the Arab-Israeli conflict, Palestine’s past has been used by both nationalist forces to construct a legitimizing national historical charter. Yet, although each camp reaches opposite conclusions and passionately promotes its own particular set of historical villains and heroes, when it comes to the Ottoman period (1516–1917), they share the same underlying set of assumptions.

Generally speaking, most Arab nationalists view the entire Ottoman era as a period of oppressive Turkish rule which stifled Arab culture and socioeconomic development and paved the way for European colonial control and the Zionist takeover of Palestine.[21] Similarly, many Zionist historians represent Ottoman Palestine before European Jewish immigration as an economically devastated, politically chaotic, and sparsely populated region.[22] The intellectual foundation for this shared image can be traced to the extensive literature published during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by Westerners bent on “discovering,” hence reclaiming, the Holy Land from what they believed was a stagnant and declining Ottoman Empire. This literature detailed the landscape in excruciating detail but turned a blind eye to the native inhabitants who, at best, were portrayed as nostalgic icons of Biblical times or, at worst, as obstacles to modernization.[23] Even Islamicist historians, who argue for a golden age of Islamic justice shattered by Western intervention in the nineteenth century, invoke the same dichotomy, which effectively partitions the history of Ottoman Palestine into two disconnected stages: traditional and modern.[24] The perception of discontinuity was so powerful that, as of this writing, only two monographs that deal specifically with Palestine during the eighteenth century have been published in English, and none covers the seventeenth century.[25] One wonders how it is possible to understand the social structure, cultural life, and economic development of Palestinian society during the Mandate period (1922–1948) on the basis of such scanty knowledge about the preceding four hundred years.

Another widely shared set of assumptions concerns the dichotomy between active and passive forces of change. Periodization reflects the assumption that change is an externally imposed, top-down process: most books on the modern history of Palestine, regardless of the nationality of their author, begin with the year 1882. The rest almost always begin with the Egyptian invasion in 1831, which is said to have initiated a process of so-called modernization that was haltingly continued by the Tanzimat in 1839 and 1856, then sealed by the arrival of European Jewish settlers in 1882. Although each of these events was of crucial significance, the implicit corollary is that the indigenous inhabitants played little or no role in the shaping of their history.

The resulting boundaries in time betray the deep concern of nationalist historians on both sides with the political legacy of the last phase of Ottoman rule to twentieth-century developments, hence the heavy emphasis in the literature on patterns of government and administration. Also, political history has been largely limited to those social groups that had direct contact with the West or were key to Ottoman administration. Similarly, far more attention was paid to those urban centers that were beachheads for Western expansion and Ottoman centralization—Jaffa, Haifa, and Jerusalem—than to the interior hill regions, where the majority of inhabitants lived until the late nineteenth century. The combined result is a general neglect of underlying socioeconomic and cultural processes and, more important, the exclusion of the native population from the historical narrative. This holds especially true for those groups that did not enjoy easy access to political position, wealth, and status: peasants, workers, artisans, women, bedouin, and the majority of retailers and merchants.[26]

The subject matter of this book was conceived, partly at least, in response to the state of the art in the field. Jabal Nablus is located in the heart of Ottoman Palestine. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Nablus was the most important of the interior cities in terms of continuous settlement, density of population, economic activity, leadership role, and degree of autonomy within Ottoman rule. It was also Palestine’s primary center for regional trade and local manufacture and was organically linked to its hinterland through deeply rooted local networks of trade. The dynamics of change experienced by its homogeneous Sunni Muslim population approximated the overall trends in Palestinian society and culture to a greater degree than did those of either the coastal cities or Jerusalem.

The focus on merchants and peasants is designed to highlight the importance of urban-rural relations to the political economy and cultural life of Palestine, as well as to take advantage of the fact that merchants are an ideal subject for researchers. The well-to-do merchant families that dominated the top ranks of the local trading community constituted a fairly cohesive and remarkably resilient group, whose engagement in this profession spanned generations. By virtue of their ownership of urban properties and the very nature of their occupation, they generated more documents than did any other social group. Consequently, it is possible to track specific families over relatively long periods and to impart an intimacy and immediacy to otherwise abstract undercurrents of change. The focus on merchants also allows researchers to examine this social group in a setting partly of its own creation: in Jabal Nablus, as in most market towns of the interior, the merchant community’s influence on the local socioeconomic and cultural life was a preponderant one.

Finally, this study begins in the early eighteenth century in order to bridge the two artificially disconnected stages of Palestine’s Ottoman past. Features usually associated with so-called modernization—such as commercial agriculture, a money economy in the rural areas, differentiation within the peasantry, commoditization of land, and ties to the world market—were present in Jabal Nablus before they were supposedly introduced by the Egyptian occupation (1831–1840), the Ottoman Tanzimat, or Jewish colonization. Similarly, so called traditional forms of social and economic organization survived well into the twentieth century. The point here is not to minimize the importance of nineteenth-century developments. Rather, it is to recognize that the regions of Greater Syria, including Jabal Nablus, had a great deal in common with the rest of the Mediterranean world and were not simply standing still until awakened by an expanding Europe and a centralizing empire. In the words of Fernand Braudel, “The Turkish Mediterranean [in the sixteenth century] lived and breathed with the same rhythms as the Christian…with identical problems and general trends if not the same consequences.”[27] No doubt Braudel’s insight holds less true for the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Still, it clearly points out that a lively pulse beat everywhere in the Mediterranean, and our knowledge of the past cannot be advanced by essentializing difference, much less eliminating the agency of the “Orient” by subjecting its history to the dichotomies of traditional/modern, active/passive, and internal/external.

| • | • | • |

Sources

In order to bring the voices of inhabitants to the fore and to impart a flavor of their world, I have drawn most heavily on local sources, which are detailed in Appendix 2. Hitherto, our understanding of Ottoman Palestine has been largely a product of a heavy reliance by historians on the central Ottoman archives and European consular reports and travel accounts. Although these sources were used in this study, their primary limitation is that they portray the inhabitants of Palestine as objects to be ordered, organized, taxed, conscripted, counted, ruled, observed, and coopted. A refreshing aspect of local sources, in contrast, is that the inhabitants come across as subjects who take an active role in the construction of their own history: they voluntarily appeared before the judge in the Islamic court, petitioned the Advisory Council (majlis al-shura), and entered into private contracts. The voices in these documents are largely their own, and their perceived priorities take precedence.

The advantages of local sources are multiplied several fold in the case of Jabal Nablus, because of the paucity of literary, consular, and central government sources on the one hand, and the fortuitous combination of local sources on the other. As a relatively small interior city whose economy was based on local and regional trade and manufacture, Nablus was of little interest to Western government officials and was, consequently, neglected in their dispatches—especially when compared with the voluminous reporting on Jerusalem and the commercial activities of the coastal cities. Lacking in great religious significance for the outside world except for the small Samaritan community, it was also of little interest to Western travelers, who invariably perceived Nablus as a temporary resting place between Jerusalem and Damascus.[28] According to James Finn, the British consul in Jerusalem during the mid-nineteenth century, “With these two exceptions [Reverend Bowen and Reverend Mills, who spent 12 months and 3 months, respectively, in Nablus] no one from our land has remained, even a few days, in this most interesting district, visited and passed through by hundreds of British travellers, for pleasure, but cared for by none.”[29] Finally, as the capital of a hill region which enjoyed a significant degree of autonomy and self-rule and in which there were no “foreigners” who held military or bureaucratic posts, Nablus remained outside the detailed supervision of the Ottoman government, at least until the mid-nineteenth century. Thus the bureaucratic documentation generated by the central bureaucracy was usually not grounded in a thorough and timely knowledge of actual developments.

Happily, this study benefits from a unique combination of local sources. The Islamic Court records of Nablus provide a wealth of detail on social life, especially in the urban sphere, and on urban-rural relations. These records, in turn, are supplemented by the correspondence of the Nablus Advisory Council and by a wide range of private family papers. Both were kindly made available to me by dozens of individuals and are used here for the first time. The Advisory Council records, which span the years 1848–1853, have greatly increased the scope and depth of our knowledge about Jabal Nablus, for they contain information on precisely those areas—political, administrative, and fiscal—which lay outside the scope of the Islamic court.[30] The most important private family papers—business contracts between merchants, artisans, and peasants, account-books, waqf endowments, personal correspondence, and property disputes—make it possible to trace the transformations in business practices, patterns of investment, and use of properties over a long period of time. They also add much-needed depth and local color to the issues discussed.

The vantage point of the central government is far from absent in these local sources. Private family papers include many original letters of appointments, land grants, and imperial edicts (firmans). The records of the Advisory Council, by their very nature, contain copies of the detailed correspondence between Nabulsi public officials and their superiors on a wide range of issues. The most important source of central government documents, however, is the Nablus Islamic Court, which also functioned as a public-records office. Hundreds of letters generated by the central bureaucracy in Istanbul, as well as by military commanders and governors of Damascus, Acre, Sidon, and Jerusalem, were copied into the court registers. Indeed, the Nablus court records probably contain the largest concentration of official correspondence dealing with this region to be found anywhere.

A few words of caution are in order. Records of the Islamic court and the Advisory Council, like those in any other archive, are products of social institutions and, consequently, are encoded with the language or discourse of these institutions. The Islamic court was, above all else, the guardian of (mostly urban) property. Aside from the administrative correspondence received and copied, all cases brought before the court—whether lawsuits, purchases and sales of immovable properties, waqf endowments and exchanges, inheritance estates, rent contracts, or matters of personal status—involved the movement, registration, or right of access to property. The Islamic court, in short, was a clearinghouse which channeled, gave legal sanction to, and legitimated the transfer of property. Consequently, the Islamic Court of Nablus served mostly the needs of the propertied urban middle class of merchants, well-to-do artisans, and religious leaders. Before the 1860s, for example, peasants were greatly underrepresented. I have used these sources mostly as literary texts; that is, as self-conscious representations reflecting the agendas of particular individuals, groups, and institutions.[31] I have often found them valuable less for what they were designed to record and more for unintended bits of information that were generally irrelevant to the outcome of each specific case. Indeed, the assumptions that underlay them and the types of information they leave out usually provided the most important clues to their significance. In addition, most disputes and inheritance cases, to name but two types of cases, were not brought before the court. Thus these records do not easily lend themselves to statistical analysis, at least not to the same degree as those of Jerusalem (where the court was a more powerful institution because of the high rank of the judges who presided over it) and of Damascus (a provincial capital). I have, for the most part, avoided the temptation of quantifying them.

The Advisory Council records pose their own sets of interpretative problems. The letters of the council, as texts, were far less predictable and standardized than were those of the Islamic court: they did not need to conform to a strict formulaic set of legal rules governing the presentation and outcome of each case. Rather, they were careful constructions—subtle, complex, evasive, probing, contingent—that reflected all the tensions of a correspondence between heads of competing bureaucratic departments who were forced to cooperate. As the appointed mediators between the central government and the local population, members of the council presented to their superiors a carefully edited image of Jabal Nablus’s political economy and cultural life, on the one hand, and creatively interpreted the demands of the central government to the local inhabitants, on the other. I have attempted to interpret them with this context in mind.

Finally, the reader will also note that I have occasionally made use of two other valuable but problematic local sources: published autobiographies and oral history. Both, of course, present difficulties stemming from the use of memory in the writing of history. My own skepticism about the usefulness of such sources for understanding the period under study was so ingrained that it was not until six years after I had started this project that I seriously considered probing them, and then only within narrow and carefully laid out limits. To my delight, they proved to be very useful. Still, I avoided treating these sources as definitive records of events that took place prior to the beginning of the twentieth century. Rather, I mined them for information on specific cultural and work-related practices and cross-checked the information against available contemporary evidence and accounts from unrelated informants.

| • | • | • |

Approach and Methodology

A common methodological challenge for social historians is how to organize the extremely fragmented information available. This particular project involved thousands of documents, each of them a closed world. This challenge is made all the more difficult by the paucity of studies on the social history of Ottoman Palestine: even the most basic demographic and economic data are in the very early stages of being unearthed for the period before the 1850s.

Although the more traditional chronological or thematic approaches have their virtues, they often achieve narrative clarity and cohesiveness by either downplaying some dimensions of the human experience or erecting artificial boundaries between these dimensions. In order to organize the details into a format which gives primacy to process and which, at the same time, relates the specific history of Jabal Nablus to the larger, more familiar themes of social history, this study has adopted a somewhat unconventional approach. I have organized the chapters around the “social lives” of four commodities,[32] the production and circulation of which were central to the livelihoods of Jabal Nablus’s inhabitants: textiles, cotton, olive oil, and soap.[33]

The phrase “social life” and the word “story” are used strictly for heuristic purposes. By the former I mean the social relations embedded in the production, exchange, and consumption of commodities. Specifically, I am referring to the linkages among economic, political, and cultural factors that determined both the meaning(s) of a particular commodity to different social groups and its trajectory through space and time. The word “story” is used in two ways: first, to emphasize that this study seeks to interpret social relations, not to expose so-called facts; and second, as an heuristic tool to express the attempt I have made in the narrative to combine cultural analysis with the language of political economy. Thus the story of the social life of each commodity becomes a vehicle for raising a number of central themes with a greater degree of complexity and, I hope, nuance than could usually done through the language of a single discipline.

These stories, I must quickly add, do not cover identical temporal spans: different commodities had different career patterns and turning points. The defining moments in the story of cotton, for example, took place during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, whereas that of soap unfolded between 1820 and the early twentieth century. That is why this book covers two entire centuries. Using such an approach is bound to create a significant degree of overlap, especially for the 1760–1860 period, which is subjected to the greatest degree of scrutiny. Each story, therefore, is not covered from all possible angles. Rather, it is used to open a window on a discrete set of relations and dynamics that complements those of other stories. The chapters are arranged the way transparencies might be overlaid to progressively add detail, color, and depth to the final image.

The story of textiles (Chapter 2) is mostly about the relationships between culture and trade and between the city and its hinterland. Textiles were the backbone of merchant communities in much of Asia as well as key markers of social status and self-identification. The majority of Nabulsi merchants dealt in this commodity, and their trading activities occupied the central physical, social, and cultural spaces of Nablus. The social life of textiles sheds light on how merchants constructed and reproduced regional and local trade networks in the context of a decentralized political structure and on how they used them to knit the rural and urban populations into one social formation. In order to elucidate the transformation of these networks over time, the bulk of this chapter is devoted to a case study of the Arafat family (no relation to Yasir Arafat), which produced nearly a dozen generations of successful textile merchants.

The story of cotton (Chapter 3) explores the connections between politics and trade, especially the points of tension between Nabulsi merchants and their regional and international competitors, in the context of the changing political landscape during the Tanzimat era. The commercial production of cotton for export has long been a feature of Palestine’s economic history, and during the eighteenth century the trade in cotton undergirded Palestine’s integration into the European-dominated world capitalist economy. Hitherto, the role of Jabal Nablus in cotton production and trade has not been detailed, even though it was the largest producer of cotton in the Fertile Crescent by the early nineteenth century. Because cotton lived on as textiles, this chapter also examines the impact of European competition on the textile industry in Nablus.

Olive oil was the most important product of the hinterland of Nablus, and soap made from olive oil was the most important manufactured commodity of the city. The social lives of olive oil and soap, therefore, can tell us a great deal about the changing political economy of Jabal Nablus, especially during the nineteenth century. It was during this period that the olive-based villages in the core hill areas of Jabal Nablus were fully integrated into the networks of urban merchants and that the soap industry underwent a remarkable expansion.

The large number of issues raised by the careers of these two commodities can be grouped under four discrete but related questions. First, how and under what conditions was olive oil transferred from the hands of peasants to those of merchants? Put differently, what were the mechanisms through which merchants appropriated the olive-oil surplus? In this regard, private family papers provide a fascinating look at how the salam (advance purchase) moneylending system was used in order to secure agricultural commodities for the purposes of manufacturing and investment. Chapter 4 also contains a discussion of the impact of moneylending on the commoditization of land, the urbanization of the rural sphere, and the rise of a middle peasantry.

Second, how was this system of surplus appropriation enforced? In the last section of Chapter 4, peasant petitions and the responses to them by both the central government and the local leaders are used to shed light on how an alliance between merchants and ruling families had taken shape by the mid-nineteenth century, especially when it came to dealing with peasant resistance to the established order. These petitions also detail peasant notions of identity, state justice, and sources of political authority and reveal the role they played in dragging the central government into the affairs of Jabal Nablus over the heads of their local leaders.

Third, how was the transformation of olive oil into soap organized economically and politically? Chapter 5 focuses on partnerships between factory owners and oil merchants who pooled their resources in order to finance this capital-intensive industry. A case study of the Yusufiyya soap factory and the estates of soap merchants from the Bishtawi family traces the reasons behind the expansion of this industry and the ways in which it was reorganized. Fourth, what was the social basis of soap production? In addressing this question in Chapter 5, special attention is given to the changing social composition of soap-factory owners. The detailed correspondence between the Nablus Advisory Council members (all of whom were involved in soap production and trade) and the central government concerning taxes on soap and the disposal of olive oil collected as taxes-in-kind allows for an in-depth look at how Ottoman reforms were perceived and molded from below.

Taken together, the stories of the social lives of these commodities shed light on the long and convoluted journey of Jabal Nablus from a semiautonomous existence under the umbrella of Ottoman rule to a more integrated and centralized one on four spatial levels. Locally, the city integrated its hinterlands into its legal, political, economic, and cultural spheres of influence to a far greater degree than ever before. Regionally, new networks of trade emanating from Beirut, Damascus, and Jaffa reoriented Jabal Nablus’s economic relations with the outside world. On the level of the empire as a whole, a centralizing Ottoman state slowly but steadily consolidated its grip on Jabal Nablus. Finally, on the international level, all of Palestine, including Jabal Nablus, was incorporated into the capitalist world economy dominated by Europe, as well as subjected to an onslaught of political and cultural incursions by foreign merchants, missionaries, settlers, and government officials.

Before tracing this journey, we need to set the stage by investigating the meanings of autonomy as experienced by the people of Jabal Nablus during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. We also need to explore the political history of Jabal Nablus and the tensions arising from the differences between the central government’s bureaucratic construction of this region as an administrative unit and its actual political and economic boundaries as a discrete social space.

Notes

1. There was no administrative unit called Palestine during the Ottoman period. This name is used to denote the territories defined as Palestine during the British Mandate (1920–1948). It is doubtful whether the name Palestine was commonly used by the native population to refer to a specific territory or nation before the late nineteenth century. In official correspondence and court cases registered in the Nablus Islamic court up to 1865 the word appeared only once, and the context precluded a nationalist meaning. This is not to say that the idea of Palestine as a territorial unit, once it emerged as part of everyday political discourse among the inhabitants, had no local or Ottoman roots. This issue still awaits a systematic investigation. For a preliminary discussion, see Beshara Doumani, “Rediscovering Ottoman Palestine: Writing Palestinians into History,” JPS, 21:2 (Winter 1992), pp. 9–10; and Alexander Schölch, Palestine in Transformation, 1856–1882: Studies in Social, Economic, and Political Development (Washington, D.C., 1993), pp. 9–17.

2. Throughout this book the name Nablus is used to refer to the city alone; and the name Jabal Nablus, to the city and its hinterland combined.

3. For example, Halil Iṅalcik, Studies in Ottoman Social and Economic History (London, 1985); Huri Iṡlamoğlu-Iṅan, ed., The Ottoman Empire and the World Economy (Cambridge, England, 1987); and I. Metin Kunt, The Sultan’s Servants: The Transformation of Ottoman Provincial Government, 1550–1650 (New York, 1983).

4. For example, in chronological order, Abdel-Karim Rafeq, The Province of Damascus, 1723–1783 (Beirut, 1966); André Raymond, Artisans et commerçants au Caire au XVIIIe siècle, 2 vols. (Damascus, 1973–1974); Leila Fawaz, Merchants and Migrants in Nineteenth-Century Beirut (Cambridge, Mass., 1983); Linda Schatkowski Schilcher, Families in Politics: Damascene Factions and Estates of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (Stuttgart, 1985); James Reilly, “Origins of Peripheral Capitalism in the Damascus Region, 1830–1914” (Ph.D. diss., Georgetown University, 1987); Bruce Masters, The Origins of Western Economic Dominance in the Middle East: Mercantilism and the Islamic Economy in Aleppo, 1600–1750 (New York, 1988); and Abraham Marcus, The Middle East on the Eve of Modernity: Aleppo in the Eighteenth Century (New York, 1989).

5. The following are but a few examples of a large body of literature that ranges from modernization, dependency, and world-system frameworks to works that draw on Marxist theories. They are listed in chronological order: H. A. R. Gibb and Harold Bowen, Islamic Society and the West, 2 vols. (Oxford, 1951, 1957); Bernard Lewis, The Emergence of Modern Turkey (Oxford, 1961); William R. Polk and Richard L. Chambers, eds., Beginnings of Modernization in the Middle East: The Nineteenth Century (Chicago, 1968); Iṅalcik, Studies; Samir Amin, Accumulation on a World Scale (New York, 1974); Çağlar Keyder, “The Dissolution of the Asiatic Mode of Production,” Economy and Society 5 (May 1976), pp. 178–196; Peter Gran, Islamic Roots of Capitalism, Egypt 1760–1840 (Austin, Tex., 1979); Bruce McGowan, Economic Life in Ottoman Europe (Cambridge, England, 1981); Immanuel Wallerstein and Reşat Kasaba, “Incorporation into the World Economy: Change in the Structure of the Ottoman Empire, 1750–1839,” in J.–L. Bacqué-Grammont and Paul Dumont, eds., Économie et sociétés dans l’Empire ottoman fin du XVII–début du XXe siècle (Paris, 1983), pp. 335–354; Şevket Pamuk, Ottoman Empire and the World Economy, 1820–1913: Trade, Capital, and Production (Cambridge, England, 1987); Iṡlamoğlu-Iṅan, ed., Ottoman Empire; I. Smilianskaya, Al-Buna al-iqtisadiyya wa-al-ijtima‘iyya fi al-mashriq al-arabi ala masharif al-asr al-hadith (Social and Economic Structures in the Arab East on the Eve of the Modern Period) (Beirut, 1989); Rifa‘at Ali Abou El-Haj, Formation of the Modern State in the Ottoman Empire, Sixteenth to Eighteenth Century (Albany, N.Y., 1991).

6. One of the most useful works outlining these issues is Roger Owen, The Middle East in the World Economy, 1800–1914 (London, 1981).

7. See, for example, Roger Owen, “The Middle East in the Eighteenth Century—An ‘Islamic’ Society in Decline? A Critique of Gibb and Bowen’s Islamic Society and the West,” Review of Middle East Studies, 1 (1975), pp. 101–112. An overview of previous critiques as well as a useful bibliography can be found in Huri Iṡlamoğlu-Iṅan, “Introduction: ‘Oriental Despotism’ in World System Perspective,” in Iṡlamoğlu-Iṅan, ed., Ottoman Empire, pp. 1–24.

8. As of late, these areas have become the object of intensive but still mostly unpublished research. By way of example, see Antoine Abdel Nour, Introduction à l’histoire urbaine de la Syrie ottomane, XVIe–XVIIIe siècle (Beirut, 1982); Suraiya Faroqhi, Towns and Townsmen of Ottoman Anatolia: Trade, Crafts and Food Production in an Urban Setting, 1520–1650 (Cambridge, England, 1984); Lucette Valensi, Tunisian Peasants in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (Cambridge, England, and New York, 1985); Ken Cuno, The Pasha’s Peasants: Land, Society, and Economy in Lower Egypt, 1740–1858 (Cambridge, England, 1992); Alixa Naff, “A Social History of Zahle, the Principal Market Town in Nineteenth-Century Lebanon” (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1972); Hala Fattah, “The Development of the Regional Market in Iraq and the Gulf, 1800–1900” (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1986); and Dina Khoury, “The Political Economy of the Province of Mosul: 1700–1850” (Ph.D. diss., Georgetown University, 1987).

9. Gabriel Baer, “The Impact of Economic Change on Traditional Society in Nineteenth Century Palestine,” in Moshe Ma‘oz, ed., Studies on Palestine during the Ottoman Period (Jerusalem, 1975), p. 495.

10. Alexander Schölch, “European Penetration and the Economic Development of Palestine, 1856–1882,” in Roger Owen, ed., Studies in the Economic and Social History of Palestine in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (London, 1982), pp. 10–87. Schölch expanded this article and incorporated it into his book, Palestine in Transformation. See also Ya‘akov Firestone, “Production and Trade in an Islamic Context: Sharika Trade Contracts in the Transitional Economy of Northern Samaria, 1853–1943,” IJMES, 6 (1975), pp. 185–209; Marwan Buheiry, “The Agricultural Exports of Southern Palestine 1885–1914,” JPS, 10:4 (Summer 1981), pp. 61–81; and Haim Gerber, “Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Palestine: The Role of Foreign Trade,” MES, 18 (1982), pp. 250–264.

11. Schölch, “European Penetration,” p. 55. By Greater Syria I mean here the areas today known as Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel/Palestine.

12. For a similar periodization, see Schilcher, Families in Politics, pp. 76–77.

13. For a concise and provocative statement of this issue, see Janet L. Abu-Lughod, Before European Hegemony: The World System, A.D. 1250–1350 (Oxford, 1989). For the Ottoman period, see Çağlar Keyder and Faruk Tabak, eds., Landholding and Commercial Agriculture in the Middle East (Albany, N.Y., 1991). For Egypt, see Cuno, Pasha’s Peasants.

14. For example, C. A. Bayly, Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansionism, 1770–1870 (Cambridge, England, 1983); David Ludden, Peasant History in South India (Princeton, N.J., 1985); and Sugata Bose, ed., South Asia and World Capitalism (Delhi, 1990).

15. Albert Hourani, “Ottoman Reform and the Politics of Notables,” in Polk and Chambers, eds., Beginnings of Modernization, pp. 41–68.

16. For example, Philip Khoury, Urban Notables and Arab Nationalism: The Politics of Damascus, 1860–1920 (Cambridge, England, 1983).

17. Owen, Middle East, pp. 52–53.

18. For a similar characterization of the role of merchants in Greater Syria, see Dominique Chevalier, “De la production lente à l’économie dynamique en Syrie,” Annales, 21 (1966), p. 67; and Owen, Middle East, pp. 88–89.

19. For a detailed discussion of the points that follow and comprehensive references to the arguments made, see Doumani, “Rediscovering Ottoman Palestine: Writing Palestinians into History.”

20. See, for example, George Adam Smith, Historical Geography of Palestine (London, 1894). Smith dwelt in great detail on the religious significance of the Holy Land and provided maps so accurate that they were consulted by the British government in defining the borders of Palestine during the Versailles Conference in 1919. As far as he was concerned, however, the history of Palestine stopped in A.D. 634 , with the Arab conquest, and did not resume until Napoleon’s invasion in 1798 except for the brief interlude of the Crusades. Thirteen centuries of continuous settlement by an Arabized Palestinian population are barely mentioned, and when they are, it is only to stress the inferiority and irrationality of the Orient as compared to the Occident.

21. For example, Abd al-Wahab al-Kayyali, Tarikh Filastin al-hadith (The Modern History of Palestine) (9th ed.; Beirut, 1985).

22. For example, Moshe Ma‘oz, Ottoman Reform in Syria and Palestine, 1840–1861: The Impact of the Tanzimat on Politics and Society (Oxford, 1968), p. v; and Yehoshua Ben-Arieh, “The Population of the Large Towns in Palestine during the First Eighty Years of the Nineteenth Century According to Western Sources,” in Ma‘oz, ed., Studies on Palestine, p. 49. For a general critique of Israeli nationalist historiography on the Ottoman period, see Doumani, “Rediscovering Ottoman Palestine: Writing Palestinians into History,” pp. 18–22; David Myers, “History as Ideology: The Case of Ben Zion Dinur, Zionist Historian ‘Par Excellence,’ ” Modern Judaism 8:2 (May 1988), pp. 167–193; and Edward Said and Christopher Hitchens, eds., Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question (London and New York, 1988).

23. This was especially true in travelers’ accounts and photographic images, both of which constantly referenced the Biblical period. For an insightful discussion of the latter genre, see Sarah Graham-Brown, Palestinians and Their Society, 1880–1946: A Photographic Essay (London and New York, 1980). Also, see Annelies Moors and Steven Machlin, “Postcards of Palestine: Interpreting Images,” Critique of Anthropology, 7 (1987), pp. 61–77. Still, the output was so prolific that a great deal of invaluable information about economic, social, and cultural life was gathered during this period. For examples, see M. Volney, Travels through Syria and Egypt in the Years 1783, 1784, and 1785 (2 vols.; London, 1788); John Lewis Burckhardt, Travels in Syria and the Holy Land (London, 1822); Smith, Historical Geography; Elizabeth Anne Finn, Palestine Peasantry: Notes on Their Clans, Warfare, Religion and Laws (London, 1923); James Finn, Stirring Times: Or Records from Jerusalem Consular Chronicles of 1853 to 1856 (ed. Elizabeth Anne Finn; 2 vols.; London, 1878); Mary Eliza Rogers, Domestic Life in Palestine (London, 1862; reprint, London and New York, 1989); and P. J. Baldensperger, The Immovable East: Studies of the People and Customs of Palestine (Boston, 1913).

24. For example, see NIMR, 1:139; and Aref al-Aref, “The Closing Phase of Ottoman Rule in Jerusalem,” in Ma‘oz, ed., Studies on Palestine, pp. 334–340.

25. Amnon Cohen, Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: Patterns of Government and Administration (Jerusalem, 1973); and Ahmad Hasan Joudah, Revolt in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: The Era of Shaykh Zahir al-Umar (Princeton, N.J., 1987). Both books focus on high politics and Ottoman administration. In contrast, a number of authors have written on the period before the supposed era of Ottoman decline: the sixteenth century. For example, see Uriel Heyd, Ottoman Documents on Palestine, 1552-1615: A Study of the Firman According to the Muhimme Defteri (Oxford, 1960); Wolf-Dieter Hütteroth and Kamal Abdulfattah, Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late Sixteenth Century (Erlangen, Germany, 1977); Amnon Cohen and Bernard Lewis, Population and Revenue in the Towns of Palestine in the Sixteenth Century (Princeton, N.J., 1978); and Amnon Cohen’s two books on Jerusalem: Jewish Life under Islam: Jerusalem in the Sixteenth Century (Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1984), and Economic Life in Jerusalem (Cambridge, England, 1989).

26. Some of these lacunae are just beginning to be addressed. For example, see two articles by Judith Tucker, “Marriage and Family in Nablus, 1720–1856: Towards a History of Arab Muslim Marriage,” Journal of Family History, 13 (1988), pp. 165–179; and “Ties That Bound: Women and Family in Late Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Nablus,” in Nikkie Keddie and Beth Baron, eds., Women in Middle Eastern History: Shifting Boundaries in Sex and Gender (New Haven, Conn., and London, 1991), pp. 233–253. Also, see Annelies Moors, “Women and Property: A Historical-Anthropological Study of Women’s Access to Property Through Inheritance, the Dower and Labour in Jabal Nablus, Palestine” (Ph.D. diss., University of Amsterdam, 1992); Suad M. Amiry, “Space, Kinship and Gender: The Social Dimensions of Peasant Architecture in Palestine” (Ph.D. diss., University of Edinburgh, 1987); and Ruba Kana‘an, “Patronage and Style in Mercantile Residential Architecture of Ottoman Bilad al-Sham: The Nablus Region in the Nineteenth Century” (M.Phil. thesis, University of Oxford, 1993).

27. Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II (2d ed., 2 vols.; New York, 1976), 1:14.

28. They rarely spent more than one or two nights. Usually, their stories revolved around the same icons: Jacob’s well at the entrance of the valley, the ancient scrolls of the Samaritan community, the lush canopy of orchards and gardens surrounding the city, and the Roman ruins in the nearby village of Sebastya. See, for example, Walter Keating Kelly, Syria and the Holy Land: Their Scenery and Their People (London, 1844), pp. 410–435.

29. Finn, Stirring Times, 2:154.

30. These records are privately owned. To my knowledge, they are the only ones of their kind that exist for the entire Fertile Crescent, other than a volume covering one year (1844–1845) for Damascus. I am indebted to Lubna Abd al-Hadi for kindly facilitating my access to them. They consist almost entirely of letters and reports, the overwhelming majority of which are responses to inquiries from the governors of Sidon and Jerusalem about fiscal, political, and administrative matters. Regular reports were also sent to the military commander of the region concerning the provisioning of troops and conscription. There are also copies of a number of petitions and letters from peasants, merchants, and employees addressed to the council. There are no records of direct communication between the council and the central government in Istanbul or any minutes of meetings.

31. For details on the types of cases to be found in the Nablus Islamic court records and the difficulties they pose in terms of quantification and interpretation, see Beshara Doumani, “Merchants, the State, and Socioeconomic Change in Ottoman Palestine: The Nablus region, 1800–1860” (Ph.D. diss., Georgetown University, 1990), chap. 3.

32. I am indebted to Arjun Appadurai for this concept. See his article, “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value,” in Arjun Appadurai, ed., The Social Life of Things (Cambridge, England, 1986), pp. 3–63. He argues (p. 13) that “the commodity situation in the social life of any ‘thing’ be defined as the situation in which its exchangeability (past, present, or future) for some other thing is its socially relevant feature.”

33. Grains were also key products of Jabal Nablus and no doubt played a crucial role in urban-rural relations. Surprisingly, however, the sources contained very little information on the grain trade, forcing its exclusion from this study. Monographs focusing on a particular commodity are not new in Ottoman history. See, for example, Roger Owen, Cotton and the Egyptian Economy, 1820–1914 (Oxford, 1969); and Schilcher, Families in Politics. The latter deals primarily with the grain trade.

1. The Meanings of Autonomy

The inhabitants of Nablus are governed by their own chiefs. . . . They are a restless people, continually in dispute with each other, and frequently in insurrection against the Pasha [governor of Damascus]. Djezzar never succeeded in completely subduing them, and Junot, with a corps of fifteen hundred French soldiers, was defeated by them.

Nablus, being the center of a rich district, and, as of old, the gateway of the trade between the northern and southern parts of the country, as also between Jaffa and Beirut on the one hand, and the trans-Jordanic districts on the other, becomes, of necessity, the mart of an active traffic. The consequence is that the inhabitants enjoy a greater amount of the comforts of life than those of any other town in Palestine.

Napoleon’s brief military adventure in Palestine in 1799 ended in failure and did not carry in its wake any significant repercussions. But the military and cultural mobilization that took place in response reveals the meanings of the autonomy in Palestine within the context of Ottoman rule. That year Shaykh Yusuf Jarrar, the mutasallim of Jenin District (sanjaq),[1] wrote a poem in which he exhorted his fellow leaders in Jabal Nablus to unite under one banner against the French forces, which were then laying siege to Acre.

Shaykh Yusuf’s poem unwittingly exposes the two major sets of tensions that informed the political life of Jabal Nablus at the turn of the nineteenth century. The first was the bureaucratic construction of Jabal Nablus from above by the central Ottoman government in Istanbul versus the dynamics of self-rule developed from below. The second was the cohesiveness of this region’s social formation and the shared sense of identity among its inhabitants versus the factionalism of multiple territorially based centers of power.

Shaykh Yusuf began his poem by expressing how the letters he received bearing the news of the invasion have brought fire to his heart and tears to his eyes. “The infidel millet [non-Muslim religious community],” he exclaimed, “are storming our way, intending to obliterate the mosques.” He then located the ruling urban households and rural clans of Jabal Nablus at that time by praising the courage and military prowess of the Tuqan, Nimr, Rayyan, Qasim, Jayyusi, At‘ut, Hajj Muhammad, Ghazi, Jaradat, and Abd al-Hadi families (in that order), beginning:

House of Tuqan, draw your swords

and mount your precious saddles.

House of Nimr, you mighty tigers,

straighten your courageous lines.

Muhammad Uthman, mobilize your men,

mobilize the heroes from all directions.

Ahmad al-Qasim, you bold lion,

prow of the advancing lines.[2]

The most striking aspect of this poem is what it does not say. Not once in its twenty-one verses does it mention Ottoman rule, much less the need to protect the empire or the glory and honor of serving the sultan. Rather, Shaykh Yusuf casts the impending danger entirely in terms of the threat to Islam and to women, and his appeal stresses local identification above all else (“Oh! you Nabulsis…advance together on Acre”). Even though all the leaders of Jabal Nablus, including Shaykh Yusf, were inundated with firmans from Istanbul announcing the invasion and calling for soldiers and money,[3] the poem leaves the origin of the letters intentionally vague, saying only that they came “from afar.”

“From afar” aptly describes the relationship between Palestine and the central government, which, except for token garrisons in Jerusalem and some of the coastal towns such as Jaffa, did not maintain a permanent military presence in this area.[4] It is not difficult to understand why. Although Palestine constituted a natural land bridge connecting Asia and Africa—and hence had strategic value, as clearly demonstrated by the 1799 invasion—it was of no exceptional material importance. Palestine did not contain any large cities that were entrepôts for international trade, such as Cairo, Damascus, or Aleppo, and its size, population, and productive capacity were all relatively small. True, Palestine, especially Jerusalem, was of special religious and symbolic significance; but Palestine was also a “frontier” region difficult to control because of its terrain and its location; it served as a buffer zone against bedouin migration from the deserts in the east. Indeed, the Ottoman authorities had such a troublesome time collecting taxes in this area that a tax-collection practice (somewhat similar to ones in North Africa) came into existence: the tour (dawra).[5] Every year starting in the early eighteenth century, the governor of Damascus Province or his deputy would, a few weeks before the holy month of Ramadan, personally lead a contingent of troops into a number of predetermined points as an aggressive physical reminder of the inhabitants’ annual fiscal obligations to the Ottoman state. Even then, taxes were rarely paid fully or on time.

Within Palestine the extent of autonomy differed from one region to another. Soon after the onset of Ottoman rule, Jabal Nablus developed a reputation for being the most difficult region to control.[6] One need only compare the divergent responses to the sultan’s firmans requesting assistance. Heeding the call for soldiers (the first firman, dated December 21, 1798, claimed that “the number of men and heroes in the mountains of Nablus and Jerusalem and their outlying parts is estimated to be 100,000 fighters”[7]), the leaders of Jabal al-Quds and Jabal al-Khalil trekked to the premises of the Islamic Court in Jerusalem. Facing the judge, each leader personally pledged a certain number of fighters, under pain of paying a large fine if he failed to deliver.[8]

In contrast, the leaders of Jabal Nablus treated the firmans as opening bids in a lengthy negotiation. Instead of dispatching fighters, they sent consecutive petitions requesting that Jabal Nablus’s share, including that of Jenin District, be reduced: first to 4,000, then 3,000, then 2,000, and finally 1,000.[9] Almost two years later the matter had still not been settled. In mid-November 1800, a firman was sent to the leaders of Jabal Nablus reminding them of the “atrocities” of the “infidel” French and, more to the point, setting a clear deadline for their contribution:

Despite repeated threats that the Ottoman armies upon their return from Egypt would punish them for their “insubordination,” “corruption,” and “stupidity,” as another angry missive from Istanbul put it, the leaders of Jabal Nablus never sent the money, at least not in full.[11] Quite the contrary, some of them looted and burned three caravansaries along the Damascus–Cairo highway—Khan Jaljulya, Qalanswa, and Ayn al-Asawir—in which supplies were stored by the mutasallim of Nablus by the orders of the central authorities, in anticipation of the Ottoman armies’ march back from Egypt.[12]Previously we sent a…firman…asking for 2,000 men from the districts of Nablus and Jenin to join our victorious soldiers…in a Holy War. Then you signed a petition excusing yourselves, saying that it was impossible to send 2,000 men due to [the need for] planting and plowing. You begged that we forgive you 1,000 men…and in our mercy we forgave you 1,000 men. But until now, not one of the remaining 1,000 has come forward…and since the armies had to depart quickly [to Egypt]…we will accept instead the sum of 110,000 piasters. . . . As soon as this order is received, you have until Shawwal 8 [February 22, 1801] to deliver the sum of 40,000 piasters…and to mid-Shawwal for paying the rest.…If you show any hesitation…you will be severely punished.[10]

These actions, about which more will be said below, were not meant as a challenge to Ottoman rule: all of the leaders operated willingly within the framework of the Ottoman political system. An important element of their power was the legitimacy conferred on them by the central government, which annually renewed their appointments as subdistrict chiefs and district governors. Nor did they welcome the French invasion or fail to take it seriously: Nabulsi fighters handed French troops their first defeat in Palestine during one of several skirmishes. According to Nimr, they also sneaked through the enemy lines surrounding Acre and entered the besieged city, to the loud cheers of the local population and Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar’s soldiers.[13] Rather, they interpreted the invasion and the Ottoman response in terms of their own local dynamics and behaved within the boundaries of the wide autonomy they had enjoyed for generations. The Nabulsi leaders had no intention of handing their fighters over to Ottoman military commanders or of joining the expedition to Egypt: their primary concern was to protect Jabal Nablus. As Shaykh Yusuf’s poem indicates, Jabal Nablus had a cohesive economic, social, and cultural identity which claimed the loyalties of its inhabitants in the face of external threats.

At the same time, however, there were political divisions and rivalries within Jabal Nablus. Power was shared by a number of territorially based rural and urban families, each of which controlled a section of the hinterland and was capable of mobilizing a peasant militia. In 1799 Jabal Nablus was also embroiled in an escalating internal power struggle between two well-defined camps, one led by the urban Tuqan household and the other by the rural Jarrar clan. The burning and looting of supplies was not a protest against Ottoman rule but a calculated act designed to embarrass and undermine the power of the current Nablus mutasallim, Khalil Beik Tuqan.[14]

It was within this local context that Shaykh Yusuf Jarrar wrote his poem. In it, he presented a constructed version of reality that best fit his purposes. By initiating the call to action, Shaykh Yusuf projected himself as first among equals and claimed local leadership in the fight against external forces that threatened Jabal Nablus and its way of life. As the leader of the faction that violently opposed the Tuqan’s drive for centralization of political power in Jabal Nablus, his poem pointedly celebrated political decentralization by giving equal praise (though in ranked order) to a large number of factions, even though some of them had little actual power. His poem also advanced an alternative framework to centralization: unity through cultural solidarity and local identification, not through political hegemony—especially not that of an urban family.

The Jarrars’ concerns were not unfounded. Since the second half of the seventeenth century, Jabal Nablus had been undergoing internal integration characterized by the city’s creeping domination over its hinterland economically, culturally, and politically. This process was driven largely by the increased importance of commercial agriculture as the primary source of wealth and upward mobility in Jabal Nablus. Accompanying changes, such as the proliferation of a money economy and credit relations, as well as commoditization of land in the countryside were, in turn, outcomes of two larger economic dynamics. The first was the flourishing of local, intraregional, and interregional trade networks emanating from Nablus under the umbrella of Ottoman rule. The second dynamic, which began during the eighteenth century, was the incremental incorporation of Palestine, including Jabal Nablus, into the European economic orbit as expressed in the commercial production of cotton for export to France.

By the time Napoleon set foot in Palestine, therefore, Jabal Nablus was already in the midst of slow and uneven transformation from a politically fragmented and economically segmented cultural unit into an increasingly integrated one internally, regionally, and internationally. The timing, causes, and inner workings of this transformation are detailed in the following chapters. But at this point, it is necessary to set the stage by exploring the structural and political contexts that defined the meanings of autonomy under Ottoman rule. The first section of this chapter sketches the basic topographical, demographic, and economic features that imparted to Jabal Nablus its autonomy and distinctiveness as a discrete social space. The second section analyzes the watershed events in the political development of Jabal Nablus from the sixteenth to the late nineteenth century; that is, the critical junctures that helped shape this region’s internal political configuration and its relationship to regional powers and the central Ottoman government. This section also contrasts the official administrative boundaries and status of Jabal Nablus with its actual development as a social space.

| • | • | • |

Jabal Nablus as a Social Space

Ever since its origins as a Canaanite settlement, the city of Nablus has been locked into a permanent embrace with its hinterland. Over the centuries the multilayered and complex interactions between these two organically linked but distinct parts generated a cohesive and dynamic social space: Jabal Nablus. The material foundations of the autonomy of Jabal Nablus were the deeply rooted economic networks between the city and its surrounding villages; and the cultural fountains of its identity were the social and political dynamics of urban-rural relations, especially between merchants and peasants. It was this combination of material and cultural transactions that made Jabal Nablus recognizable to outsiders as a discrete entity and, more important, made it feel like home to its residents by inculcating in them a sense of regional loyalty. In the words of Reverend John Mills, “The inhabitants [of Nablus] are most proud of it, and think there is no place in the world equal to it.”[15]

In this general sense, Jabal Nablus was similar to many others that existed under the umbrella of Ottoman rule, and the centuries-long existence of these social spaces explains the strong regional identifications that are still an important part of popular culture in Greater Syria.[16] For example, one can talk about Jabal Lubnan (Mount Lebanon), Jabal Amil (also known as Bilad Bishara), in what is today southern Lebanon; Jabal al-Druze (Hauran), in today’s Syria; and Jabal al-Khalil and Jabal al-Quds, whose urban centers were Hebron and Jerusalem, respectively.

This is not to say that these social spaces had clear and unchanging borders, nor that the nature of interaction between city and hinterland was everywhere the same. For instance, the urban centers of Jabal Nablus, Jabal al-Quds, and Jabal al-Khalil occupied different points along the spectrum of possibilities during the Ottoman period. Hebron was largely an extension of its hinterland, its economic life for the most part focused on agricultural pursuits and on providing essential services to the surrounding villages. Jerusalem, in contrast, stood somewhat aloof from its hinterland primarily because of the external infusions of economic and political capital that its religious, symbolic, and administrative significance attracted. Nablus lay somewhere between the two: its connections to the hinterland were absolutely vital, but it also contained a large manufacturing base and was a nexus for substantial networks of regional trade. Its hinterland, moreover, contained some of the richest agricultural lands in Palestine, as well as the largest and most stable concentration of villages and people. The city of Nablus did not possess the glamour or drama of Jerusalem; nor did it suffer from the relative sleepiness and obscurity of Hebron. Rather, it served, at least during much of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century, as the economic and, occasionally, political center of Palestine. Not surprisingly, Jabal Nablus—often referred to as jabal al-nar (mountain of fire)—played a leading role in the 1834 revolt against the Egyptian forces, in the 1936–1939 rebellion against British rule, and in the Palestinian uprising (intifada) against Israeli occupation that exploded in 1987.

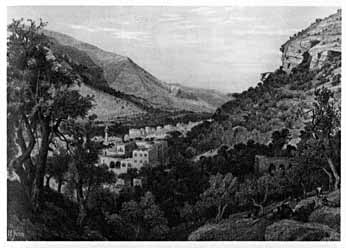

The City of Nablus

“The immediate vicinity of Nabloos is remarkable for the number of its trees, and its luxuriant vegetation; it is, indeed, one of the most beautiful and fertile spots in all Palestine.”[17] Practically every visitor to Nablus—from Muslim travelers in the Middle Ages to young Englishmen in search of adventure in the nineteenth century—described the appearance of the city in similarly flattering terms.[18] Embedded between two steep mountains in a narrow but lush valley and surrounded by a wide belt of olive groves, vineyards, fruit orchards, and a sprinkle of palm trees, the ancient city of Nablus has long been described as resembling, in the words of Shams al-Din al-Ansari (d. A.H. 727, A.D. 1326–1327), a “palace in a garden” (see Plates 1–3).[19]