Costumes for Impersonations

So far as interesting costume is concerned, the drama impersonations loom large beside these simple prayers in conventionalized dress.

The Pueblo Indian acquires ideas from almost everything with which he comes in contact. With him the mimetic art is a natural one: he can take on a new characterization as easily as he can put on a costume.

The rigid rules governing the significant use of certain garments and decorations have been mentioned before. Likewise, each impersonation has its own delineation and a prescribed pattern of action. When a serious variation occurs, a new person results. This correlation of costume and character is of some importance. There are so few actual garments that the arrangement of them is limited, yet the many hundreds of impersonations require careful delineation to distinguish one from another. The difference may be only the color of a mask or the shape of a feather ornament, each combined with significant ornamentation.

The earliest and most universal form of impersonation was effected

by the use of cured animal heads and skins. "Impersonation of supernaturals is a religious technique world-wide in distribution. The two most common methods of impersonation are by animal heads and pelts, and by masks, but impersonation by means of body paint, elaborate costume and headdress, or the wearing of sacred symbols is by no means uncommon. In the pueblos, where all magic power is imputed to impersonation, all techniques are employed."[9]

Animal impersonations probably preceded all other impersonations. Animals were believed to be man's brothers, who by their existence made it possible for man to live. Animal headdresses and costumes were used as magic and decoy. By impersonating the animal he wished to kill, a hunter could come very close to a herd without being observed. By performing a dance before the hunt, the Hunt group believed that they could please the spirits of the animals, which would then permit their earthly bodies to be killed.

Many legends surrounding the animals form the background for these dramas. The dramas differ from one village to the next in conception of costume and in number and variety of characters. In the Buffalo Dance of San Juan there appear two Buffalo men and one Maiden,[10] whereas the San Ildefonso version requires two Buffalo men and two Maidens. Parsons says that on one occasion at Taos one hundred and forty Buffalo appeared with but two Deer characters.[11] Elk and Goat dances are also remarked, and some elaborate dramas include a large number of different beasts.

Buffalo Dance, San Ildefonso.

—The Animal Dances are usually given in winter. That is the time of year for hunting because cultivated food is scarce and the animals are then forced down from their mountain homes. At San Ildefonso I saw a Buffalo Dance performed, contrary to custom, in August, 1936. The dancers, two men and two women, came from the round, outside kiva of the Turquoise people,[12] appearing through

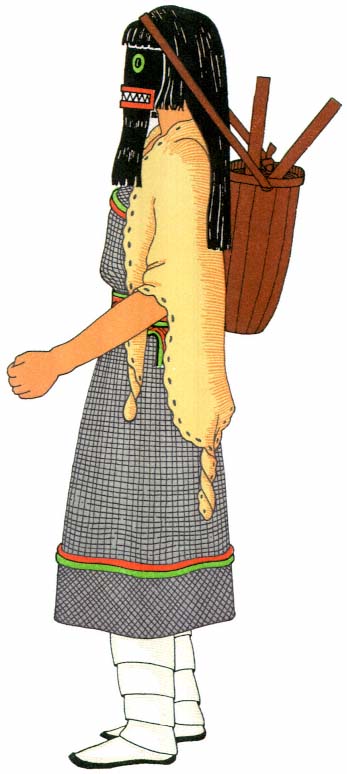

Plate 31.

Natacka Mother, Hopi. Female deity impersonation.

the hatchway about mid-morning. The bodies (pl. 21) of the men were painted a dark earth brown with white crosses on each side of the chest and abdomen and on each arm. They wore soft, cream-colored deerskin kilts, with a writhing black serpent painted through the center, and a border of blue and yellow the bottom of which was edged with metal tinklers, small cones of tin which hung from deerskin thongs and knocked together with every rhythmic movement of the dancers, making a pleasing, silvery sound. A red woven belt held the kilt in place, and a string of bells around the waist added a deeper, more musical tone, punctuating the less melodic vibrations of rattles and drums. Below the knee the legs were encircled by bands of brown buffalo hair which sustained, in front, a floating eagle feather. White moccasins with buffalo-hair heelpieces encased the feet. Arm bands were of buffalo hair. Several strands of white shell beads were worn around the wrists, and many necklaces of turquoise and white shell were around the neck. Just under the chin was a large abalone shell. A gourd rattle with a fringe of bright orange-dyed goat's hair was carried in the right hand, and evergreen and a bow and arrow with four eagle feathers swinging from the string appeared in the other. A large piece of the heavy neck fur of the buffalo over the head and shoulders made a shaggy frame for the little that could be seen of the face. The horns on each side had eagle's down fluttering from their tips. On the back of the buffalo headdress, moving gracefully up and down, was an ornament composed of a fan of eagle wing and macaw tail feathers with the quill ends covered with orange-dyed goat's hair and a large bunch of green and yellow parrot feathers. A small downy white feather was tied directly on top.

The Buffalo Maidens (pl. 22), impersonating the mothers of the game animals, appeared in dresses made from large, hand-woven, white cotton blankets embroidered at top and bottom. Over this, like a short tunic, was a man's embroidered white dance kilt. Both dress and tunic were fastened on the right shoulder. The panel of stylized cloud, rain, and

earth symbols made a line of decoration from shoulder to waist. The great wrapped moccasins of soft white deerskin gave a modest air to the costume, and the heelpieces of black and white skunk fur rounded it off. White shell beads were wound around the wrists, and strings of turquoise and white shells hung in heavy festoons on the breast. A necklace of turquoise with an entire abalone shell encircled the base of the neck. Arm bands of brilliant orange-dyed goat's hair made blobs of color midway in the figure. The black hair hung loose in a solid gleaming mass, while in direct contrast a downy white eagle feather floated from the top. At the back an ornament rose from the neckline majestically above the head. It was composed of a great bunch of green and red parrot feathers, edged in orange-dyed goat skin, supporting three macaw tail feathers—scarlet shafts of color. In each hand formal bouquets were carried. These were composed of shining eagle and parrot feathers surrounded by the dull green of spruce needles and edged with creamy white olive shells[13] which added beauty and supplied a clicking accompaniment to the rhythmic accent of the rattles.

Each dancer was in character from the moment he appeared above the rim of the kiva. With lowered eyes, the men danced with a heavy, steady, downward beat. They were young men, their bodies full of vigorous strength. Their movements, however, were not excessive, but poised and controlled in easy, graceful posture. The maidens were young and handsome. Their clear brown skins were ruddy with health and this contrasted strongly with the positive whiteness of their garments and the jet blackness of their hair. They danced demurely with downcast eyes. Their steps echoed rather than followed those of the men. Never by glance or movement did they betray a consciousness of the spectators, who might crowd in closely. Between the dance patterns the performers were in constant movement, their tinklers rattling and their bodies intent on the regular motion of a stately trot. Their leader, a priest in the somber pueblo dress of the conquistadors, was almost concealed by his great blanket. He car-

ried a feather insigne and sprinkled meal for the dancers' 'road'. The chorus was made up of a knot of men, grouped on one side, who danced gently to the rhythm of their own chants. In their midst a large drum was beaten with hypnotic cadence.

The Buffalo Dance, Tesuque.

—In the Tesuque Buffalo Dance a group of men and women, numbering eighteen couples in all, perform an entire routine as a frame for three dancers and their leaders. These line dancers — if one may call them so for convenience — come from one kiva and perform in the dance places around the village. Returning to the plaza, they stand in two lines facing each other. Here they are joined by the five Buffalo Dancers: two men in buffalo costumes and a woman in a white embroidered mantle dress constituting the group of three, and two other men, one the father or leader and the other the hunter. This second group performs a serpentine between the two stationary lines.

Figure 25.

Headdress of the side dancers, Buffalo Dance. Six eagle feathers bound

with cornhusks and a buffalo horn are tied to a deerskin with thongs.

The costumes of the line dancers are significant in reflecting the qualities of both the Buffalo impersonations and the usual ceremonial attire, a uniform which contributes to the particular performance and yet keeps its place as a subordinate element. When I saw them, the men dancers wore rough buckskin kilts, with belts and anklets of bells, and low moccasins with skunk heelbands. A blackened horn projected from the right side of the head, while on the left was a fan of six or more eagle tail feathers. Both these decorations were attached to a beaded headband.[14] The hair was queued or short. Thin strips of pelt hung from the arm and leg bands. In the right hand was a gourd, in the left a bow and arrow. The upper

and lower parts of the face were painted black, with a broad red stripe across the bridge of the nose. In one dance line the bodies were blackened, in the other they were painted red. On the backs were splotches of white paint, and the thighs, forearms, and hands were whitened.[15]

Dance of the Game Animals, San Felipe.

—The drama of the many horned animals includes all those who, friendly to the Indian, formerly provided him with food during the long winters. The actors are clothed to impersonate the buffalo, deer, mountain sheep or elk, and antelope,[16] as these were the principal game animals of the region surrounding the ancient Pueblo lands.

The San Felipe play begins at dawn when a lovely dark-skinned maiden runs swiftly toward the mountains behind the pueblo. She is the chosen mother of the animals, and she goes to lure them into the village. She is accompanied by young men dressed as hunters, in white buckskin garments similar to those of the Plains Indians. They carry bows and arrows and sprigs of evergreen. All the young people chosen for this part of the ceremony must be fleet and sure of foot, for their purpose is to run as fast as the beasts and drive them into the village amid the great applause of the spectators.

There follows a secret rite in one of the ceremonial chambers, and the entire group emerges to continue the action of the play and to dance ill the plaza, where small evergreen trees have been set up to suggest a forest. Each group, including a scattering of hunters, interprets the movements of the beasts they are impersonating. The Buffaloes, with black bodies, deerskin kilts, and heavy, shaggy buffalo headdress, dance with the solid weight of large and lumbering animals.[17] The Buffalo Maiden dances just behind the leader, her white dress banded at the waist by a red woven belt. On her head is a tight cap covered with iridescent black feathers and topped by the two small horns of the buffalo cow. Her legs are wrapped ill high white moccasins ending in skunk-fur heelpieces. Quantities of

Plate 32.

Natacka Daughter, Hopi. Female deity.

turquoise and white shell beads hang around her neck. In one hand she carries a rattle wand to which are attached feathers, evergreen sprigs, and animal hoofs.

Next come the Elk, lofty and regal in their horned headdresses; and then the antlered Deer approach quickly with shy and fugitive grace. Bird down and puffs of cotton trim the prongs of horns and antlers, and from their foreheads fan-shaped visors of slender sticks rise upward and forward. A red fringe of goat's hair covers the quill ends of an eaglefeather ornament which is tied, tip downward, on the hair at the nape of the neck, and sprigs of evergreen fall over the shoulders. White shirts cover the bodies, and from waist to knee are kilts either of dark blue native stuff with a red and green strip through the middle, or of Hopiembroidered white cotton cloth. Around the waist the white plaited sashes with tasseled ends are knotted at the back to suggest the tails of the animals. White, crocheted leggings, tied at the knee with red yarns, end in low moccasins edged with black and white skunk-fur heelpieces. A light, short stick is carried, and it is decorated with a spray of evergreen which is bound to the center with cotton cord. These sticks are used to support the weight in different postures and to imitate the movement of the forefeet of the animal when running or leaping.

The Mountain Sheep appear with giant horns rising on either side of the caplike base. The Antelope wear on their bodies snug-fitting suits with the backs painted yellow and bellies white to simulate the animal's skin. On the heads are antelope horns. They frisk gaily, their feather tails bobbing up and down. The impersonators dance upright, often leaning forward to rest on the canelike props.

Interrupting the last dance, the animals break away and run for the hills. When they are 'shot down' (that is, when they are caught by townsmen or hunters) they lie inert and 'dead' while they are carried to the kiva across the hunters' backs. The successful hunter receives a spray of evergreen for his reward.

The Eagle Dance.

—In his dramatizations the Pueblo Indian represented birds as well as animals. He watched the eagle soaring overhead. This was the one bird which, with his great, strong wings, could fly out of sight in the blue upper distances. Certainly he must fly to the very sun, and surely he had direct intercourse with the Sky Powers and told the Great Father all that befell his human children! Hence, the Eagle impersonation has become very important and is often connected with medicine and curing.[18]

This dance drama expresses the supposed relationship between eagle and man and the deific powers.[*] It is performed by two young men, who, costumed to represent eagles, faithfully imitate the birds' movements.

The keynote of the eagle dress is stylized realism (pl. 23). The gleaming brown-black of the upper body is interrupted by a vest-shaped patch of bright yellow on the chest. This is outlined with eagle down. The lower arms, legs, and bare feet are as yellow as the legs and talons of an eagle, and the face is yellow with a brilliant red patch across the chin. The smart, soft, buckskin kilt, the color of cream, displays through the center an undulating snake design, and at the bottom of the kilt are strips of blue, yellow, and black, while the tinklers, made of tin and forming the fringe, click together throughout the dance. This garment is held in place by a leather belt of turquoise blue banded by a string of sharp-toned brass bells; the body beneath is painted white. Sprays of spruce stick up above the waist. A sweeping, fan-shaped tail of eagle feathers is attached at the back, and perfectly fashioned wings of long eagle feathers, bound to a strip of heavy buckskin, cover the arms and shoulders from finger tip to finger tip. The hair hangs loose, and the head is covered with white down or raw cotton, forming a deep, snug cap, to which a long, yellow beak is fastened so that it protrudes just above the wearer's nose.

It is obvious that the dancers have made a close study of the eagle's flight, so exact are they in the reproduction of the movements. They

* In the eastern pueblos it is always preceded by fasting and retreat.

create the illusion of soaring through the clouds, hovering over the fields, and perching on high aeries. Again, they strut along the ground, or fiercely swoop, or circle wildly—their bells tinkling like rain—as if disturbed by an approaching storm.

When women accompany the Eagle men in the dance, they are beautifully garbed in snowy white dresses, fringed sashes, and moccasins, accented with jet black embroidered bands, skunk fur, and gleaming hair.[19] Black and white eagle feathers are carried in each hand, and form an ornament at the back of the neck where the only relief in color harmony is the long, tapering points of yellow macaw feathers set at equal distances around a plaque and showing like a halo behind the head.

A further step in the process of impersonation is the masked being. We do not know whether this grew out of the animal and bird characterizations, but it is interesting to contrast the masked and unmasked representation of the same character in two villages so similar in material ways of life. The Rio Grande Eagle appears real and natural beside the Hopi Eagle (pl. 24), yet their origin is the same. They were nurtured on the same beliefs, and they developed with similar objectives. The Rio Grande Eagle wore a kilt of buckskin because the beautiful, soft-tanned hides from the plains were accessible to him. The Hopi Eagle, on the contrary, wore a kilt of native cotton which the Hopi cultivated and wove into cloth. The distinguishing body paint, kilt, brocaded sash, woven red belt, and pendent foxskin are the conventional items of dress for the masked supernatural, and the anklets, wound in colored yarns, are typical of Hopiland. The Hopi eagle wings are more carefully designed and have greater perfection of finish. The rough leather, where the quills of the long wing feathers are fastened, is covered with white down. On the back is a long, flat plaque or shield of buckskin edged in red horsehair, for "the eagle is the chief of birds, and so he wears the shield on his back."[20] At length there is the mask, a distorted object which does not resemble man, and which resembles a bird in nothing but the yellow hooked beak in

front. The helmet of leather, painted the sacred turquoise blue, has large projecting red tab ears and round black and white wooden eyes. The black chevron above the snout is always found on the masks of certain birds of prey.[21] Around the crown is a green yucca fillet tied in front, and from the top wave long, downy white eagle feathers and red and yellow parrot feathers. At the back, two tall black and white eagle feathers stand upright from a great pompon of small black and white feathers which is a part of the full and beautiful collar of like material.

Introduced from Hopi to Zuñi, the Eagle Dance in both villages is a prayer that the eaglets in the nests on the rocky mesa ledges may be increased in number, so that there will be a plentiful supply of fine feathers for the garments of the supernaturals in the other world.[22]