Decoration

When primitive man first sought to make himself attractive, he chose from his environment objects which were bright or colorful and wore them in his hair, strung them about his neck, looped them about his middle, or otherwise applied them to his person where application was possible. Garments evolved from this desire for ornamentation of the body and were used as protection from the elements or the immodest eyes of men. Hilaire Hiler points out that "ornament often exists without clothing, but clothing seldom, if ever, exists without ornament."[96]

Articles of clothing of the Pueblo Indian are the bases upon which the arts of the painter, the dyer, the embroiderer, and the weaver are practiced. Garment ornamentation is achieved through painting in pigment directly upon the surface of the fabric, the application of colored yarns or other materials by embroidery or appliqué, and the weaving of variously dyed yarns into a patterned fabric.

The effect of ornamentation varies with the method and the material used. Heavy embroidery raises the surface and stiffens the garment in the area in which it is applied, and painted designs may cause a cloth to hang rigid because of the adhesive matter used to make the pigment cling to the surface. On the other hand, a cloth made of dyed yarn may not vary at all from its uncolored prototype, since the pigment, though changing the color, does not affect the physical character of the cloth.

Color.

—Since love of color is an inborn trait of the human race, it is not surprising to find the Pueblo Indian of the Southwest exercising it, albeit unconsciously. Colors abound in his kingdom of sandy space and limitless sky. The earth shows a myriad hues, played upon incessantly and with endless change by the brilliant sunlight or the passing clouds. The sky exhibits the pageantry of all those shifting forms of day and night, summer and winter, fair weather and foul, which are called the elements.

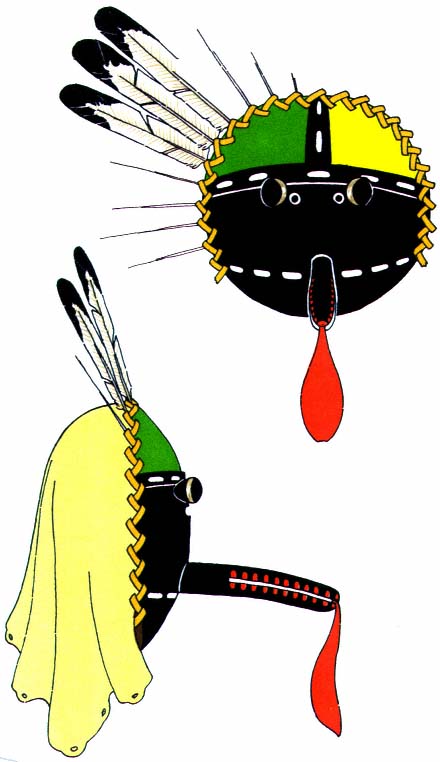

Plate 14.

Basketry mask. Feathers are held

in place by a braid of cornhusk.

The parade of color passes from the pale iridescence of dawn through the white noon to the golden flamboyance of sunset, and on into the crisp blue-black of the star-pierced night. It is seen in the red and purple where the watercourse has gashed the mesa side; in the brittle-edged clumps of dark green piñon against a golden monotone of roiling sand; in the soft gradations of green and silver sagebrush and cactus-strewn flats; and on the great rolling mesa tops where blankets of purple lupin and yellow sulphur flowers have been carelessly flung across the sweep of space. The Indian had but to step to his housetop to see around and above him all these wonders of nature. He began very early to relate them to certain phases of his life.

Out of these associations grew a kind of symbolism in which color represented ideas and objects, mythical and real alike. Colors were related to the six directions: yellow to the north, blue to the west, red to the south, white to the east, many colors to the zenith, and black to the nadir. The origin of these associations is clothed in mystery.[*] It is obvious that yellow colors the sky to the north before the angry winter storms sweep down from the mountains, and it has been suggested that the Pacific Ocean to the west accounts for the blue.[97] Red is applied to the south because of the ruddy warmth of summer, and white to the east because it suggests early morn and the rising sun.[98] The many colors of the zenith reflect the sky from which all colors come, and the nadir is black because of the dark inner worlds from which in myth the Pueblo peoples emerged.

Paralleling these directional hues are the colored ears of corn used on the altars and incorporated into the legendary background of the social and religious life. Certain of the supernaturals are characterized in sets which correspond to the cardinal directions and colors. During ceremonies these supernaturals appear in the masks and body paint of their world quarters. The Zuñi Salimapiya[99] are an interesting example of one of these

* Some of the pueblos either lack this association altogether or have a variant. "Taos appears to have no directional association with color" (Parsons, 1936a , p. l05). In Isleta only five directions are recognized and there the colors are: east, white; north, black; west, yellow; south, blue (Parsons, 1932, p. 284).

series (pls. 5, 6). There are twelve of them, two for each direction. They appear together only once every four years; at other times two of them, each of a different color, may be seen simultaneously. The black may appear with the many-colored, representing respectively the nadir and the zenith; again, the yellow may appear with the blue, representing the north and the west. In 1879 Matilda Stevenson saw two of these directional supernaturals at Zuñi, which she describes as follows:

"They represented the Zenith and Nadir, the one for Zenith having the upper portion of the body blocked in the six colors, each block outlined with black. The knees and the lower arms to the elbow have the same decoration; the right upper arm is yellow, the left blue; the right leg is yellow, the left blue. Wreaths of spruce are worn around the ankles and wrists. The war pouch and many strings of grain of black and white Indian corn hung over the shoulder, crossing the body. The upper half of the Salimapiya of the Nadir is yellow and lower half black; the lower arms and legs and feet are yellow, the upper arms and legs black. He wears anklets and wristlets of spruce, a war pouch, and strings of black and white corn."[100]

Ruth Bunzel, writing in 1932, says the Blue Salimapiya "has his mask painted with blue gum paint, his body with the juice of black cornstalks ... thighs white ... he wears a special kilt called the Salimapiya kilt. It is embroidered like the ceremonial blanket with butterflies and flowers."[101] He also wears a blue leather belt and spruce anklets, and his feet are bare.

The impression of the general public, when viewing Indian motifs in costumes and decoration, is that they are composed of purely symbolic patterns. This is rarely true. Many designs are used only for decoration, and if by chance they symbolize an object, quality, or idea, it is merely by association. The emotional response to color association differs with the group, and what becomes a symbol to one group remains only a decoration with another.

Green suggests grass, and it may mean life and fecundity. Blue-green

is reverently used, as it is always associated with the sky. It is a 'valuable' color and of great religious import. The blue prayer stick is male and connotes the sun; the yellow represents the female and the moon. The turquoise stone is regarded with great reverence and the wealth of a man is displayed by the quantity of turquoise he wears about his neck. "Yellow on the face represents corn pollen, and brings rain;"[102] and yellow body paint is used by the Squash groups or Summer people. On the other hand, "red paint on the body is for the red-breasted birds, and the yellow paint for the yellow-breasted birds, and for the flowers and butterflies and all the beautiful things in the world," and again, "the spots of paint of different colors ... are the raindrops falling down from the sky,"[103] or those same spots may represent the drops of blood of a little boy who, in a myth, was killed by the supernaturals. They ever afterward wore the spots on their masks.[104]

From the frequency with which designs are repeated on like objects, and the same colors used, one can be certain that there is a definite symbolic pattern for the ceremonial use of color. We do not know whether the source of this symbolism is known to others besides the priests who prescribe it and who have acquired their knowledge from priests of the preceding generation.

The association of color is one thing, the application another. The range of hues used by the Pueblo Indian was limited to the colors that were available and to the manners in which they could be used. Materials were colored by three methods: dyeing, a process by which a permanent union is brought about between the material to be dyed and the coloring matter applied to it; staining, a method by which colored particles become entangled in the surface of the fiber but can be removed by washing or rubbing; and painting, by which a pigment is applied to the surface. McGregor says:

"Dyes or pigments used in coloring yarns or fabrics may be divided into two general classes: organic and inorganic. In prehistoric cotton

fabrics the inorganic dyes are by far the most common, and consist largely of three colors: red, produced from hematite or some other iron oxide; yellow, from a yellow ochre; and blue or green, produced from copper sulphate. These inorganic dyes may be readily determined by a superficial examination with a medium-powered microscope, for the dye material does not penetrate the fiber but clings to it in the form of grains. Organic dyes seem to consist of only black, dark brown, and a light blue. These dyes are relatively permanent and cannot be washed out, as can the inorganic types."[105]

Paints and stains.

—The processes of painting and staining which employ inorganic pigments are used to color the face and body, articles made of skin, wood, and nature forms, and certain fabrics for which the required colors cannot be obtained in permanent dyes.

These earth colors are found in the mountains and valleys surrounding each pueblo. Most of the villages are thus able to obtain their own supplies, but often color in the form of cakes or powder is obtained by trade with other Indians. The Zuñi procure their turquoise blue mask paint, ready for use, from the Santo Domingo because they believe the color is better.[106] Mrs. Parsons relates that a Jemez Indian once asked her to get some red face paint from the Hopi for him. "He said they had the best."[107] The hue of these pigments varies greatly with the locality in which they are found and the purity with which they can be obtained. A report on Acoma suggests that the original earth color is none too pure, but by separating the ground particles a fairly clear color is obtained. "A yellowish rock is ground fine and the dust mixed with water. The sediment is thrown away after being allowed to settle twice. The third accumulation of sediment is kept."[108]

Some colors come in rock form; others are a clay. "Iron tinged the earth red, brown, yellow, orange and intermediate shades. Copper produced

Plate 15.

Mountain sheep mask, Hopi. Molded horns of deerskin carry

symbols of clouds, rain, and lightning. The vizor is of basketry.

Figure 15.

Containers for pigments used in painting ceremonial objects.

the blues and greens. Black came from iron and magnesium."[109] The pigment, from whatever source, is ground in a stone mortar or on a metate with a mano. The process of grinding is often a special ceremony at which the young girls are invited to do the grinding while the men sing to them.[110] At other times the grinding is a secret rite and is done in the kiva by the society head and his helpers.[111] The ground powder is mixed with water and used directly, or it may be combined with an adhesive, substance, such as piñon gum or the juice of yucca fruit,[112] to make it more permanent. Another method of fixing a permanent color is to squirt over it a water in which ground-up pumpkin seeds have been steeped for a long time.[113] A shiny surface is made possible by mixing the paint with yucca juice or the yolk or white of eggs.[114] A glaze of albumen from the egg white may be applied over the paint,[115] or a spray of cow's milk blown from the mouth makes the object bright and shiny.[116] Grease is mixed with body paint to make it adhere and also to impart a sheen.[117]

Paints are applied with the fingers, a stick, or brushes of yucca fiber. A piece of yucca leaf is selected and chewed to separate the fibers and cleanse them. This makes a very good brush. A different brush is used for each color. The pigments are mixed in small pottery cups made specially in groups for that purpose and decorated with designs relating to water and rain. Sometimes flower petals and shells are ground and mixed with the powder to give it more 'power' or to make it more sacred.

Even today the paints for ceremonial purposes are of native make. It is a rare and decadent society which permits the use of any commercial paint on the masks, body, or dress of a dancer.

White is obtained from a white clay (kaolin) which is soaked in water or ground and used as a powder—the counterpart of the fuller's earth, or

white clay paste, used by Greek and Roman artisans to cleanse and whiten their cloth. All white garments are treated with it before they are worn. This clay is found up and down the Rio Grande and is traded to the Zuñi by the Acoma.[118] Masks are always painted white before any other color is applied. This forms a ground coat to fill up pores and give a smooth surface. White is often used as a body paint or powdery.[119]

Black may be obtained from various sources. A pigment in common use comes from an ore (pyrolurite, a hydrated oxide of manganese)[120] which is mined.[121] This is used on prayer sticks and masks. Chimney soot is also used, especially for the eyes of a mask—being, for that purpose, mixed with the yolk of an egg to produce a gloss.[122] Corncobs, carbonized and ground, make a highly valued paint for masks. At Zuñi, they are found in the ancient ruins and carefully preserved for this purpose. Similar to this is the charcoal of willow which, when ground, is mixed with water for a body paint.[123] Corn rust or fungus mixed with water is used especially for a body paint; mixed with yucca syrup, it makes a shiny black paint which is used for masks.[124] An iridescent blackish substance ("black shiny dirt") is found in the water washes after a rain. It is probably the fine grains of quartz, sphalerite, and galena, the last-named being a ground concentrate of zinc ore.[125] This is mixed with grease and applied to the body, or it is mixed with yucca juice or piñon gum and applied to masks. Masks are also made to shine by the use of mica (micacious hematite), which is applied over black with some form of adhesive.[126]

Pink is a body paint used especially by the sacred clowns, the Mudheads (pl. 40), and by the Kokochi and other masked gods.[127] It is a clay[*] obtained by the Zuñi from the shores of the Sacred Lake where the kachinas live. Every four years a pilgrimage is made there to secure it. It is kept in chunks until wanted, and then is wet with the tongue and rubbed on the body or mask.

The reds and yellows are ochers or oxides of iron. These rock forma-

* Kaolinite or a similar hydrated silicate of alumina.

tions, hematite and limonite, constitute the rugged edges of the mesa and the weird towering shapes that stand, massive and solitary, on the desert throughout all the great distance from the Grand Canyon to the Rio Grande.[128] Certain cliffs or mounds produce colors of greater purity than others do, and these the Indians have mined for centuries. One cave on the north side of the Grand Canyon produces a fine red ocher which is traded to the Hopi by the Shivwits, a tribe of Indians who dwell to the north.[129] Other mines are within easy reach of all the pueblos. The red is generally ground on a stone with water until the water becomes red. It can be used directly on the masks or the body. If light red is desired, the red water is mixed with pink or white clay. At Zuñi the yellow ocher is ground with the petals of yellow summer flowers (the buttercup) and abalone shells. This makes a very potent 'medicine.' When mixed with water, it becomes a sacred paint.[130] Another yellow is made of corn pollen. When mixed with the boiled yucca juice, it produces a glossy paint. It is thought to be flesh color.[131] At Laguna the faces of the dead are painted with corn pollen.

The most important color is turquoise. This blue-green paint is an oxidized copper ore (azurite and malachite in a calcite matrix).[132] It is found in the mountains to the east of the Rio Grande and is traded by the pueblos of those regions to the Hopi and Zuñi. Cakes or balls of this color are made by grinding the ore to a fine powder, mixing it with water, and boiling with piñon gum. The cakes can then be put away and kept indefinitely. A method of painting masks at Acoma with this pigment is described as follows: "One puts some of this substance into his mouth with eagle feathers, chews it for some time, then blows it onto the mask. The breath is expelled with it, giving the effect of a spray."[133]

There are also stains from plants which are used to color the body. Pink is produced by boiling wheat with a small sunflower,[134] and purple can be obtained from the chewed stalks and husks of black corn. An example is seen on the body of the blue-masked Salimapiya (pl. 6). The

purple obtained from crushing the berries of barberry is used on the body and for painting ceremonial objects.[135]

Dyes.

—The organic colors or dyes of the Pueblo were very limited. Certain trees and bushes yielded colors that were used to dye the yucca fibers, but with the advent of cotton the process became difficult. It is a well-known fact that cotton is the hardest of all fibers to dye. Specimens of native dyed cotton are rare and the colors are always drab and faded. It appears, then, that the prehistoric Pueblo people had no cotton garments of strong colors, and this made the need of brilliant ornamentation imperative.

Brown dye could be obtained from alder bark, dried and finely ground. It was boiled until it became red, and then was cooled. Deerskin soaked overnight in this liquid turned a brilliant red-brown. This was the favorite color for moccasins (pl. 33), Hopi fringed leather kilts, arm bands, bandoleers, and anything fashioned of deerskin. Sometimes the alder bark was chewed, and the juice ejected upon the deerskin, which was then rubbed between the hands.[136] Cotton cloth took only a small quantity of this dye and turned reddish tan.

A blue dye was made from the seeds of sunflowers.[137]

New colors came with the introduction and use of wool. Woolen fibers take dye much more readily than cotton. By this time the Navaho had learned the art of weaving from the Pueblo Indian. Alongside this knowledge of weaving there developed a new method of dyeing, as is evidenced by the well-known Navaho blankets. Unquestionably there was borrowing back and forth between the two groups. It is possible to say, then, that the Pueblo native dyes were similar to those of the Navaho.[138] These dyes were made from the leaves, stems, and roots of plants and shrubs and certain earth fillers, with use of piñon gum and a mordant of juniper ashes to make the color lasting. There were black, dark red, green, and

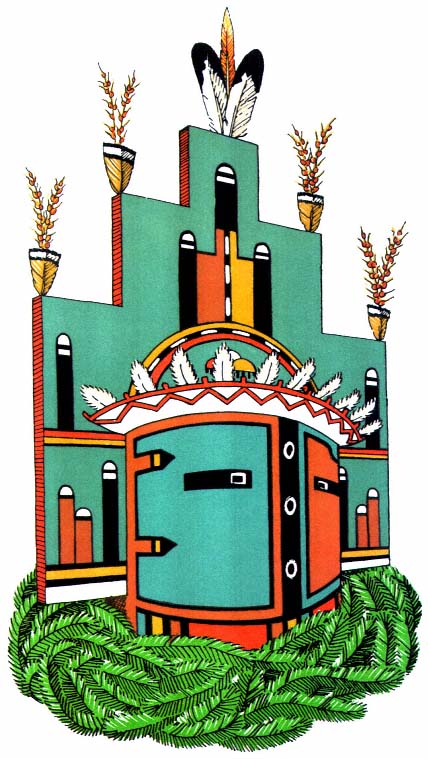

Plate 16.

Humis mask, Hopi. The terraced tablet over the helmet is

decorated with symbols of the rainbow and germinated seed.

the various yellows. From time to time indigo was imported from Mexico, along with other dyestuffs.

Since 1880, good commercial aniline dyes have largely taken the place of the native colorings. It is now rare to find a woolen blanket colored with native dyes, and even rarer to find, on cotton cloths, woolen embroidery which is native dyed. I have seen a few specimens in museums and private collections. The native dyes are soft and exquisite in their beauty. Once these are seen, the modern greens and reds appear harsh and overbrilliant.

Embroidery.

—Pueblo Indian embroidery is a pure form of ceremonial decoration. It is found on dance kilts, ceremonial mantles (pls. 7, 22), and the dresses made of hand-woven strips of cotton cloth (pl. 1). Occasionally the ordinary blue woolen dresses are embroidered with simple borders. The designs are highly conventionalized and dynamically abstract, with bold forms and geometric patterns.

"The art of embroidery as now practiced is a fairly recent one and is probably an outgrowth of the painting on kilts mentioned by Espejo or of the raised patterns found in weaving."[139] It is probable that no needlework decoration was done by the Pueblo Indians before the coming of the white man, since no examples are extant which do not utilize woolen yarn. It was the white man who brought the sheep. The yarns employed today are almost always commercial yarns or aniline-dyed hand-spun wool.

Rectangles of white cotton cloth, equal in size, are made into ceremonial mantles and dresses; one is worn hanging from the shoulders, the other is fastened around the body and held with a belt. They are similar to the wedding robe of the Hopi bride, which is completely white. It is later embroidered by her husband or a male relative for her use in ceremonies.[140] The same style of robe is made for god impersonators and priests. The decoration motif at the bottom "takes the form of a broad band of black wool with two vertical stripes of green appearing at intervals. On these broad borders the only space not completely covered is

a thin meandering line of the white cotton base which appears diagonally crossing the black and green. This white design-line creates a strong off-balance movement to the general vertical embroidery, seeming to exaggerate the movement of the dance in which it is used."[141] The upper edge of this band is terraced, and frequently through its center may be seen diamond-shaped medallions with designs of clouds, rain, squash flower, and butterfly symbols[142] —brilliant jewels of color. The design motif may differ among the pueblos, but the effect is always the same. The upper border is narrower and has only the green stripes and white meandering lines to break its solidity.

The rectangular dance kilts are also made of white cotton cloth and embroidered with various patterns. The Hopi type has a vertical band in black, red, and green up and down the two short sides. A special Zuñi type has a wide border similar to the mantle, with terraced top and colored medallions. It is worn by the Salimapiya. Other kilts have designs and borders which vary according to pueblo and impersonation.

In the earlier days a few of the women's woolen dresses were embroidered. The Zuñi used a deep blue woolen yarn in identical designs on the upper and lower borders,[143] and at Acoma they embroidered similar borders in color.[144]

Most of the embroidery for the Pueblos is done by the Hopi men, who are also the weavers. Special orders are filled for the priests of other pueblos who want mantles or kilts for their ceremonies. "Hopi embroidery—an art practiced only by men—is governed by very rigid rules."[145] The patterns are traditional and can be easily recognized on any dancer.

During the process of embroidery the cloth is stretched on a frame made of sticks with pointed ends.[146] The pattern is never indicated on the cloth, but is built up by counting threads. The material is folded for a center line and the border is worked in each direction so that it will come out even.

In early days, bone awls were used to poke the yarn through the cloth;

now, steel darning needles have taken their place. A simple back stitch is used, leaving much thread on the right side and picking up only a few threads on the under side. The white meander lines are made by carrying the yarn under certain threads, leaving their natural white exposed.

Colored designs are incorporated in sash ends through the brocade weave (p1. 31). (This process was described in the section on weaving.) Limited by the warp and weft of the loom, these designs are geometric. Colors are worked into separate patterns. A characteristic diamond shape in the center of the panel is made up of a border and triangular sections. Above and below run bands of black, green, and blue, with white figures picked out in the basic weave.

In the anklet another decorative effect is achieved. An oblong piece of deerskin or leather is slit internally in narrow lengthwise strips, leaving the ends uncut. These strips are wound with colored wools in geometric patterns (pl. 24). Porcupine quills and horsehair create a similar pattern. The quills, with points cut off, are moistened to make them pliable. Slit or flattened by drawing between the teeth or over the thumbnail, they are folded around the leather strip and caught by a series of half hitches in the horsehair (pl. 8).[147] Today they are sewn in place by stitches through the center of the strip. When stained with soft bright colors from berries, roots, and flowers,[148] porcupine quills make exquisite designs with a mosaiclike quality. This is a method of decoration employed by the Plains Indians. It is probable that the Pueblos acquired the technique from them.