2—

Spoken Dramas

Spoken drama in prewar China remained the entertainment of an urban, educated minority. That all changed with the eruption of war, however. If the arts are considered useful tools of propaganda, spoken drama must rank as one of the most effective for the powerful impact it produces not only on the eyes and ears of its audiences, but also on their emotions.

Immediately after the war broke out in Shanghai in August 1937, a group of theater and cinema activists formed the Shanghai Theater Circle National Salvation Association (Shanghai xijujie jiuwang xiehui). Thirteen drama troupes were organized (figure 3) by such people as Song Zhidi (1914–1956) and Cui Wei (1912–1979) (Troupe 1), Hong Shen and Jin Shan (1911–1982) (Troupe 2), Zheng Junli (1911–1969) and Zhao Dan (1915–1980) (Troupe 3), and Yu Ling (1907-) (Troupe 12). With the exception of the tenth and twelfth companies, which remained in Shanghai, the other eleven, under the slogan "Spreading patriotic news to the countryside and to the battlefields," left sheltered city life and plunged into the remote villages of interior China to begin the ambitious task of rallying the Chinese people for the resistance movement.[1] On 1 August 1938, after a centralized propaganda effort was launched by the Third Section (literary propaganda, headed by Guo Moruo) of the Political Department, under the direction of the Military Affairs Commission, the thirteen Shanghai Theater Circle troupes were reorganized into ten Anti-Japanese Drama Companies (Kangdi yanjudui). Each comprising thirty members (who received 25 yuan per month in salary), these troupes were instructed to continue the task of spreading news and educating

Fig. 3.

Staging a street play in Wuhan, summer of 1938. The partially

covered sign reads, "Anti-Japanese Drama Troupe." Courtesy

of Lü Fu.

the masses about the war. The Nationalist general Chen Cheng (1897–1965), director of the Political Department, aired his hope for this ambitious undertaking: "These ten drama companies are tantamount to ten divisions of troops."[2]

Besides government-sponsored troupes, other drama groups such as student propaganda teams, amateur drama clubs, children's traveling drama corps, and local drama companies also sprang up, traveling to different corners of China to awaken the peasants by means of plays and songs.[3] This profusion of drama clubs grew so rapidly that by the early 1940s more than 2,500 such units had appeared in China, involving more than 75,000 men and women.[4]

The war drastically changed the nature of modern Chinese drama. Not only was the new drama that thrived during the eight-year War of Resistance against Japan intensely political, but also, because so many dramatists and actors migrated into the interior after the outbreak of the war, it soon lost its elitist urban nature.[5] No longer a mere cityoriented entertainment medium, the drama now became a primary propaganda channel for communicating with broad masses of rural people. And as the new theater redefined the limits of the stage experience and challenged the old norms, the center of attention shifted from the play to the audience.

Popularization

Armed with poor and simple tools but full of enthusiasm and energy, young Chinese dramatists and student activists roamed the countryside to begin an unprecedented campaign of mass political education of the common people. It did not take long for them to realize that they were facing an audience very different from the one they were used to: less educated and less sophisticated peasants, living in a society still largely dependent on oral communication. The peripatetic nature of the dramatists' endeavor also meant that they had to adjust constantly to complex local cultures and dialects as they moved from one village to the next. The playwrights thus faced the problem of redesigning urban spoken drama to meet the needs of a rural population. Clearly, enlightenment of the masses could be achieved only if Chinese drama were popularized.

These twin wartime aims were by no means new. "Popularization" (dazhonghua) had long been a major concern of May Fourth intellectuals, who, under the slogan "Going to the people," sought simple but effective ways of enlightening the general public.[6] The enthusiasm continued unabated into the 1930s, while taking on an added political significance. The newly founded League of Left-Wing Writers, under the influence of Qu Qiubai (1899–1935), raised the banner of a "people's language," sparking heated debate among Chinese intellectuals.[7] In the end that debate reached far beyond language per se, to include the nature and the audience of Chinese theater.

Nor was the idea of using spoken drama to educate the peasants a wartime novelty. Already in the late 1920s, recognizing the potential of the modern drama to combat rural illiteracy and poverty, the National Association for the Advancement of Mass Education (Zhonghua pingmin jiaoyu cujinhui; NAAME), under the leadership of James Yen (Yan Yangchu, 1893–1990), had tested this new ground. Xiong Foxi, hired by James Yen to oversee the drama program, became the pivotal figure in the mass education and rural reconstruction campaign in Dingxian, Hebei province, in the period 1932–1937.[8] Xiong's early interest in using spoken drama to foster social change had led him in 1921 to cofound the People's Drama Society with Mao Dun and Ouyang Yuqian. Like many May Fourth iconoclasts, Xiong challenged established values and attacked old literary genres. He believed that traditional Chinese drama was an archaic, elitist form of entertainment, ill suited to meet modern challenges. New ideas and new techniques were needed to convey modern messages and to raise

the literacy of the peasants. To him, spoken drama had unique virtues as a medium of communication, for it entertained and educated at the same time. As he put it, instruction came best under the guise of delight. Not surprisingly, "Education in entertainment" (yu jiaoyu yu yule) was the Dingxian drama workers' watchword.[9]

Championing the idea that spoken drama should serve society and reflect the struggle of life, Xiong was committed to mass education and firmly believed that "every genuine piece of art must be popularized."[10] During his stay in Dingxian, Xiong wrote scripts, many of which employed local dialects; designed open-air theaters; formed numerous peasant drama troupes (nongmin jutuan); and broke new ground in training peasants as actors. Such plays of his as The Butcher (Tuhu) and Crossing (Guodu), staged and acted entirely by peasants, enjoyed wide popularity among rural audiences.[11] By employing peasant actors, Xiong hoped to "blend the actors and audiences together,"[12] creating a sense of community and meshing what was happening on the stage with what went on in real life. His highly innovative efforts won him a reputation as "the pioneer of popular theater in China."[13]

Because Xiong Foxi's Dingxian experiments, innovative and fascinating though they were, were confined to a specific locality, they were never fully appreciated by his more urban-oriented colleagues. The war with Japan suddenly made Xiong's ideas, if not his actual work, important. Young Chinese students, filled with patriotic fervor, flocked to the countryside, plunging into "the jungle of the reality."[14] As they threw themselves into the patriotic cause, however, these zealous young propagandists encountered problems far beyond any they might have imagined. Most important, they discovered that good intentions were no match for harsh realities. Although the notion of bringing the patriotic message to rural areas was obvious, how to get there was just the first of many significant challenges. In 1939, George Taylor noted these telling statistics about one province in China: "Hopei [Hebei] is a province of 153,682 sq. km. in area and has less than 4,000 miles of motor road, of which less than 50 miles are paved."[15]

Apart from extreme hindrances to communication, young dramatists soon found that presenting a play comprehensible to the uncultured villagers could be a difficult, if not impossible, task. One actor recalled his frustrating experience:

Rural plays are starkly different from urban ones. In fact, there are differences between a metropolitan play and a small city play, and a county play is not exactly the same as a village play.

During our six-month stay in Guilin, we rehearsed a few plays and staged them a couple of times. The audiences were mostly townspeople, educated, so the responses were quite good. We then thought that we would have a similar result if we put on a show in the rural areas….

We first mounted two shows in a large village: Little Compatriots in Shanghai [Shanghai xiao tongbao ] and We Have Beaten Back the Enemy [Diren datui le ]. Some spectators raised the following questions: "What are you people doing up there on the stage? How come those young fellows act so recklessly up there? Why aren't there any gongs and drums [as in traditional opera]?" Our conclusion was that the country folk definitely needed a kind of play bustling with noise and excitement….

We ran into snags when we staged another show in a different village. The villagers simply did not understand what we were performing. They didn't know what we were talking about [on the stage] and did not understand the play at all. They couldn't even recognize Japanese troops. We had to immediately cut short the dialogue and increase the action scenes, at the same time making it more comical. But all of this still fell on deaf ears: there simply was no response from the audience![16]

This was by no means an isolated incident. Similar complaints were voiced in all quarters.[17] The poor reception of spoken drama in the rural areas no doubt stemmed in part from the villagers' unfamiliarity with the new art form. In essence, though, the conflict was one between two different perspectives and sets of values: as urban playwrights projected their own views and tastes on the peasantry through this new art form, rural audiences demanded their accustomed music and plot in a traditional play. In his propaganda activities in rural Shandong in 1937, the drama activist Cui Wei was sensitive enough to recognize the problems and make a few adjustments:

Literacy among Shandong peasants is extremely low. If we tried to transplant urban plays to the rural areas, the peasants would not have understood them. Since there was no appropriate play, I decided to write a few myself…. My simple play [about Japanese brutality in Manchuria] was enthusiastically received. After the show, an old peasant stepped forward and spoke to us in tears. He told me that his son had been killed by the Japanese in Manchuria. [Since the villagers liked the play so much,] they insisted that we should stay, so we staged a revised play, A Village Scene [Jiangcun xiaojing ], the same night. They wanted to give us money and went so far as to carry our baggage. We spent at least a week in this village [near Qingdao], putting on a few more

newly revised plays…. [I found that] those artistic plays that moved urbanites to tears did not have much impact when staged in the villages. Perhaps only intellectuals could appreciate them, but they were certainly incomprehensible to the peasants.[18]

The task of bringing enlightenment and news to the masses—what young dramatists called "from Carlton [Theater] to the street" (cong Kaerdeng dao jietou)[19] —was indeed a challenge. But what was to be done? The transformation of modern urban drama from an elitist to a mass art, many believed, had to begin with its popularization. "When dealing with a rural population who have no idea of what the term 'Japanese imperialists' means," Hong Shen suggested, young performers should communicate with the peasants in simple language and by staging drama in the guise of storytelling.[20]

Indeed, the language issue was an important one. Drama critics often complained that the metaphors and abstract idioms of urban plays baffled peasant audiences and consequently dampened their interest in the drama. To communicate effectively with the masses, simple, colloquial language—what Hong Shen called "hometown language" (xiangtu yu)[21] —should be used. The use of dialects, in particular, was encouraged; dialects were usually down-to-earth and extremely lively and had the ability to convey the nuances of a locality and its inhabitants better than any other form of communication. "If we intend to go to the villages and win the acceptance of the rural folk," one playwright contended, "we have no choice but to use dialects."[22] Many dramatists (such as Hong Shen) did experiment with this idea, incorporating local sayings into their plays, for example. Yet mastering a dialect required time and dedication, not to mention a quick grasp of local sensibilities. And time was something young activists did not have as they hurried from one place to another to spread the patriotic gospel.

In the move to the countryside, playwrights and actors had to inject a sense of realism into their efforts, which included portraying the peasantry accurately. Realism, however, must finally be judged not by the style of a play, but by how comprehensible it was to its audience. An urban youth would naturally have difficulty playing the role of a humble peasant in a truly credible manner. Their life-styles were utterly different, and, as drama critic Zhou Gangming noted, their world outlooks were miles apart.[23] The best type of play, many drama critics argued, would be one in which peasants themselves acted. Thus Xiong Foxi's idea of "blending the actors and audiences together"

received renewed attention during the war, the concept now imbued with a fresh political connotation. "For intellectuals to stage a play to entertain the common people is not as good as letting the people do it themselves," contended one dramatist.[24] Tian Han concurred: "If we wish to cause new drama to take root and sprout in the villages, we must foster the young peasants of that region as drama cadres to form themselves into healthy peasant companies."[25] By encouraging peasants to participate in their plays, young dramatists attempted to form a physical if not intellectual bridge between themselves and the illiterate.

Was enlisting peasants as actors a successful undertaking? In fact, apart from Xiong Foxi's prewar attempt in Dingxian, we have no sure evidence to suggest that such an idea was put into practice during the war. What scanty information there is indicates that it remained very much a paper resolution. Traditionally, rural China was largely impervious to outside influence. Even the basic goal of drawing peasants' attention to a new and unconventional type of play was at first a difficult problem for young dramatists. Deep-rooted notions of localism, combined with ignorance, more often than not prompted villagers to look with suspicion upon outsiders. "Because our troupe was composed of both men and women, sometimes we were [erroneously] charged by conservative local leaders with corrupting public morals and ended up in jail," one young participant angrily recalled.[26]

The Street Play Lay Down Your Whip

If young performers found mastering dialects a challenging task and bringing peasants into their plays remained a lofty dream, they were relatively successful in creating many ingenious dramatic forms to correspond to their itinerant life. These included:

1. Teahouse plays (chaguanju) —Actors would enter at a teahouse and intermingle with the customers. They would then perform a play in this setting, creating an atmosphere that conveyed the idea that the performed events actually occurred in the tearoom.

2. Parade plays (youxingju) —These would take place on festival days. Staging a play during a parade, actors distributed propaganda leaflets along the road.

3. Puppet plays (kuileiju) —Traditional puppets were used to portray patriotic events.

4. Commemoration plays (yishiju) —Plays such as The Life of Dr. Sun Yat-sen (Guofu yisheng) and The Marco Polo Bridge Incident

(Lugouqiao) commemorated influential political figures and historic incidents.

5. Newspaper plays (huobaoju) —Many of these were impromptu scenarios based on important news of the day, keeping the public abreast of recent happenings both at home and abroad.

6. Street plays (jietouju) —Short plays were staged on the street, with active audience response a key component.[27]

Despite their superficial differences, all these new plays shared certain characteristics: an informal setting, a current theme, simple language, and direct contact with the populace, the intent being to instill patriotism into the people. Instead of focusing on the text, these plays emphasized performance and action. Instead of resorting to fixed staging, they relied heavily on improvisation and creativity. And instead of displaying the skill of the actors, they stressed the importance of exchange with the spectators.

Among spoken drama forms, the newspaper play and the street play ranked as the two most popular and influential. Described as "living newspapers" (huo de baozhi),[28] newspaper plays reported recent armed conflicts, extolled heroic acts, exposed the enemy's brutalities, and related news and information, serving as a simple but much-needed communication channel for the common people. Local events and current news played an important role in the plays, part of the dramatists' effort to breed a stronger sense of realism and familiarity among local audiences.[29] As one actor recalled, many newspaper plays were written on the spot to depict very recent incidents, and members of the traveling troupes would often collect stories on the road, which they quickly turned into new plays.[30] This kind of improvised product, though rarely polished, gave the poorly equipped troupes added flexibility. Since one of their main purposes was to inform the public of the news, timeliness was considered of central importance.

The street play—defined by the literary critic Guangweiran (Zhang Guangnian, 1913-) as "a play that can be staged on the street in the quickest way, with the simplest equipment, and that can communicate in a most popularized format"[31] —was even more popular than the newspaper play. Like the newspaper play, the street play was relatively short (usually one act lasting less than thirty minutes), presented by a small group of four or five performers, and dealt largely, though not strictly, with current affairs.[32] The street play, however, had more complicated plots and was more flexible. Most important, street plays emphasized audience participation. Actors regularly disguised them-

selves as spectators, mingling with the crowd and then joining the play at a predetermined time as if the act were part of the audience's response; in this way they created a dramatic effect unmatched in other plays.

The popularity of the street play during the early phase of the war redefined the meaning of Chinese spoken drama in a time of national crisis. A street play was characteristically an improvised piece grounded in simplicity, flexibility, and interaction, unified by the theme of war, and serving as a rallying call for resistance. In contrast to an urban play, a street play had little, if any, scenery. Words were deemphasized while action was encouraged, the assumption being that words were often too sophisticated for the illiterate peasants to understand. Engaging facial expression and fist-clenching histrionics generated passions that high-sounding patriotic slogans like "Down with Japanese imperialism!" (dadao Riben diguozhuyi) simply could not. As one dramatist wrote, if the desire was to communicate effectively with the audience, "text [was] less important than performance."[33] Much of the language that remained in the street play was colloquial and direct; and instead of long didactic harangues, songs might be used to carry uplifting messages.

The novelty of the story and the unfamiliarity of characters in the spoken play challenged the audience's usual identification with the actor in a traditional play. Moreover, the fact that the audience, not the actor, lay at the core of a street play challenged the traditional division between the stage and the spectator as well as the notion of the audience as passive observers. It thrust the spectator into an active role, creating constant communication between the stage and the audience and, ultimately, a sense of community. Staging was not a display of individual talent, but a creation of what Richard Schechner called "relations" between actor and spectator.[34] In the end, the line between art and life was deliberately nullified, and theater became an act of exchange rather than a one-way communication.

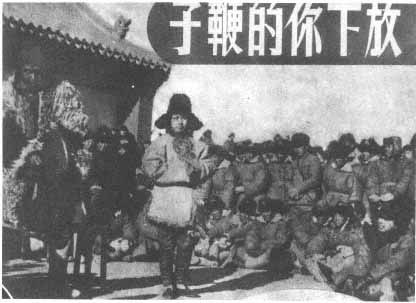

Among numerous street plays, Lay Down Your Whip (Fangxia nide bianzi) was arguably the most popular (figure 4). A provocative piece written in 1931 by Chen Liting (1910-), then a primary schoolteacher in Nanhui, a county near Shanghai, Lay Down Your Whip underwent many transformations and assumed many forms during the war. It became the best-received and most influential street play in the early years of the wartime drama movement.[35] The piece, inspired by an earlier one-act play, Lady Mei (Mei niang) by Tian Han (who in turn drew his ideas from Goethe's Wilhelm Meister),[36] concerns two ref-

Fig. 4.

A traveling drama troupe staging the street play Lay Down Your Whip in 1937.

From Dongfang zazhi 34.4 (16 February 1937): n.p.

ugees, an old man and his daughter, Fragrance (Xiang Jie), who escape flood, callous landlords, and oppressive government in their hometown. Destitute and homeless, they eke out a living as street performers. Though she is physically enervated, the old man pressures his daughter to perform acrobatics and sing on the street, particularly the popular melody "Fengyang Flower-Drum" ("Fengyang huagu"). Enraged by her poor performance, the old man raises his whip to punish the girl. A young worker (an actor in disguise) comes charging out from the crowd, shouting, "Lay down your whip!" He reproaches the old man for tormenting his own daughter. Surprisingly, Fragrance comes to her father's defense. She recounts her family's misfortune and the plight of her hometown folk, who suffer miserably under the tyrannical government. At the end, the young actor appeals to the now deeply moved spectators, calling on them to fight against government oppression: "We must resist those who coerce us to live a life of starvation and homelessness."[37] Because of these strong anti-Guomindang overtones, Chen did not put his name on the script for fear of government persecution.[38]

A failure when it debuted on 10 October 1931 in Nanhui, Lay

Down Your Whip had better luck in the following years, especially after the December Ninth Incident of 1935, when Japanese incursions into north China became more aggressive and when radical students increasingly demonstrated their dissatisfaction with the GMD government's policy of appeasement vis-à-vis Japanese imperialism.[39] The play rapidly assumed a new look: instead of running away from corrupt government and natural disasters, the old man and his daughter were now escaping the brutality of the Japanese occupation in Manchuria. Thus what was originally an anti-GMD play took on an increasingly anti-imperialist, anti-Japanese stand. Instead of treating a class struggle between landlords and peasants, the story now focused on a confrontation between two nations; and instead of appealing to his compatriots to resist oppressive and inept government, the young actor had a different message to offer: "If we do not unite quickly to defend ourselves against Japanese aggression, we will soon meet the same fate as our countrymen in Manchuria." The theme song was also replaced by the "September Eighteenth Melody" ("Jiuyiba xiaodiao"), which became an instant hit:

The sorghum leaves are green, so green,

On September 18th came the barbaric Japanese troops.

They occupied our arsenals and seized our towns;

They slaughtered our people and pillaged our land.

Oh, they slaughtered our people and pillaged our land.

Although our armed men numbered hundreds and thousands,

They meekly surrendered the city of Shenyang.

The play's intensity and brevity were ideal for a propaganda piece. The simple yet well-wrought dialogue between father and daughter depicted a painful experience to which the audience could relate, and the passionate appeal of the young man spurred anger and sympathy. According to many eyewitness accounts, people responded with an outburst of emotions ranging from profound sadness to furious indignation, touching off waves of patriotic enthusiasm.[40] The play had an added meaning in concluding with an ominous warning of impending doom.

The popularity of such street plays as Lay Down Your Whip did not depend solely on the patriotic outburst. The large degree of flexibility the actors enjoyed with regard to content was also important, for it allowed them to improvise a plot that spoke to a particular location and a particular time. The father and daughter's place of origin in Lay Down Your Whip, for example, did not remain fixed; they came

from Manchuria when it fell into the hands of the enemy, but when the Chinese capital of Nanjing was captured bloodily by the Japanese in December 1937 that city became their hometown. Any location devastated by Japanese troops served equally well. The theme song varied also. Besides the "September Eighteenth Melody," patriotic songs such as the "March of the Volunteers" ("Yiyongjun jinxingqu") and "Fight to Recover Our Homeland" ("Da hui laojia qu") graced some versions of the play.[41]

The peripatetic life of a traveling troupe added another dimension of flexibility to the street play. Actors were fairly free to move around—like an agile "light cavalry," as one described it[42] —and this allowed them to bring war news and patriotic messages to a host of places. If the task of Chinese dramatists, as one commentator suggested, was to wage "drama guerrilla warfare," the very core of the repertoire was street plays and newspaper plays.[43] It was important to get away from the urban nature of Chinese spoken drama, said the drama critic Liu Nianqu; Chinese dramatists should write plays closer to the life of the common people. In this way, not only would the urban youths of the traveling drama troupes gain a new perspective on life, but they would also have the opportunity to "sow seeds everywhere they visited." Someday these seeds would grow into trees all over China, Liu said.[44]

Clearly, Chinese wartime dramatists placed great emphasis on a play's audiences.[45] In contrast to the novel, drama is a shared experience that attempts to forge an instant bond with the audience, evincing, in the words of Susanne Langer, "immediate, visible responses of human beings."[46] As one writer insisted, "Actors must 'merge with the audience' [dacheng yipian ]."[47] The audience issue, in fact, came to be accepted as the very key to a play's success or failure, to such a degree that other essential ingredients of a play such as the staging, acting, and mise-en-scène were considered relatively insignificant.

To stress the role of audiences is to underscore the importance of communication in drama. In Lay Down Your Whip, the interaction between performers and onlookers becomes the most dynamic aspect of the theater gathering. Signals and meanings are transmitted from stage to audience and back again. This reciprocity of the theater demands that the spectator not only respond but also participate, and ultimately empathize with the actors. Guangweiran pointed out that since the stage was often surrounded on all sides by spectators, a feeling of physical intimacy resulted that allowed the actor to hold the audience with maximum intensity.[48] The sudden appearance of an actor

from among the onlookers also added a dramatic touch and an element of surprise. In Lay Down Your Whip, the young actor's entrance onto the stage defused an apparently dangerous situation and encouraged the audience to participate vocally and emotionally, eliminating the physical as well as the emotional gap between audience and characters. At the end, instead of applause there was patriotic shouting: "Down with the aggressor!" and "Recover our lost territories!"

Lay Down Your Whip, in large part because of its simple yet powerful plot, but also because of its combination of sorrow and fervent nationalism, became so popular during the early years of the war that it was staged throughout China.[49] One drama troupe performed it eighteen times in a single day in a remote Shandong village.[50] The play also appeared in different versions and under different titles. Cui Wei, for example, rewrote it, giving it a new name: On the Starvation Line (Ji'exian shang); two other writers called their versions simply Fragrance (Xiang Jie).[51] Although Lay Down Your Whip was unmistakably an anti-Japanese play, to a large extent it was also a political indictment of the GMD's ineffectual appeasement policy. Predictably, therefore, the play attracted the ire of the Nationalists, who banned it in the mid-1930s.[52] Yet right-wing dramatists, for their part, did not hesitate to turn this popular play around and use it to fuel anti-Communist sentiments. In their versions, the father-daughter team do not come from Manchuria; they flee from a notorious Communistcontrolled area![53]

The tremendous success of Lay Down Your Whip helped usher in a new era of Chinese spoken drama. Street plays appeared in profusion during the war, creating a lasting impact on the minds of the people. Among the most popular were Sanjiang hao (literally, "How wonderful are the three rivers," referring to the Heilong, the Songhua, and the Yalu rivers), The Last Stratagem (Zuihou yi ji), and March to the Front (Shang qianxian).[54]Sanjiang hao portrays the wisdom and bravery of a resistance hero in the northeast, Sanjiang hao, who not only successfully eludes capture but also at the end persuades his pursuer to join him.[55]The Last Stratagem praises the shrewdness and the unyielding spirit of a patriot in his resistance against the Japanese.[56] These two plays were so enthusiastically received that they, together with Lay Down Your Whip, were collectively known as Hao yi ji bianzi (meaning literally "What a wonderful strategy, the whip"), a phrase combining the last words of the three titles.

Nevertheless, wartime street plays were not without their problems. Although constant travel was exciting for young performers, in prac-

tice it caused physical exhaustion and often proved dangerous. The pressure of the resistance campaign took its toll, with many actors contracting tuberculosis, heart disease, and stomach ailments, mostly from malnutrition and exhaustion; some died of these maladies,[57] while a few were killed by enemy gunfire at the front.[58]

In many ways, putting on a street play was an adventure into the unknown. An outdoor performance was vulnerable to such difficulties as unreliable location, unpredictable weather, and shifting groups of spectators whose actions could not be precisely anticipated. The blurring of the line between performers and audience meant a radical shift in command and control. The spectator had the potential for radically changing the play and leaving organizers and performers at a loss. The future became precarious, even hazardous. Incidents of verbal and physical assault against actors portraying collaborators and war profiteers were abundant.[59]

More important, one crucial issue was never fully addressed by young Chinese dramatists: the proper relation of performance and text. The street play's emphasis on collectively evolved performance as a better, more creative form of theater than one based on text conveyed an implicit yet unmistakable hostility toward literature and words. The majority of wartime street plays were impromptu pieces, unpolished and possessing little artistic value. The issue of immediate relevance around which the productions revolved rarely translated into long-lasting artistic excellence and more often than not failed to please the more cultured segment of the audience.

This deficiency partly explains why the street play began to wane in popularity two years into the war and why many began to call for a renewed focus on the text.[60] Yet to say that wartime street plays in general lacked artistic merit is not to say that they exerted little impact. On the contrary, particularly in rural areas their impact was enormous. In all this, it is important to recall that young drama activists did not just bring street plays to the remote villages; they also channeled news, held mini-exhibitions about the war, and taught basic civil defense to the peasants.[61] This novel experience was as important for the dramatists as for the peasants they performed for, providing them all with a sense of sacrifice and togetherness created under the constant fear that their country would soon be occupied by the enemy. The political crisis was unprecedented, as was the zest and the sense of mission that motivated thousands of young men and women to reach out to the masses. The great majority of them had no experience in mass political education. Street corners and temple fairs thus became

schools for them as well as for their audiences. What gave meaning to their efforts and distinguished them from their predecessors, they believed, was that they backed up their words of commitment with practice and their lives. Although many drama troupes were short-lived owing to the perennial shortage of funds, the loose structure of most groups, and the mental and physical fatigue of the performers,[62] the sense of accord that these young people tried to create was intense and real. The war politicized and unified almost every aspect of life, and drama not least of all.

Despite the many difficulties encountered by the peripatetic dramatists, ample evidence shows that wartime newspaper and street plays had a significant impact on the common people, villagers and urbanites alike. American journalist Edgar A. Mowrer, for example, observed the following scene in Chengdu during the war:

My friend Victor Hu…took my arm and urged me forward. But before we got close enough to see or hear much, the proceedings stopped and instead there went up from the crowd a roar of approval: "Hao, hao! (good, good)," which one may hear in any popular Chinese theater….

"What was it?"

"It is called The Death of General Wang Sze-chung [Wang Sizhong ] at Tientsin [Tianjin ], a well known educational play."

"And who are the players?"

"High-school student propagandists. They travel all over the country and by their rather simple spectacles arouse the patriotism of the people and their indignation against the Japanese. There are a good many of these little theatrical troupes."[63]

Enthusiastic responses were recorded in rural areas, too, as one Chinese observer noted:

They [the amateur dramatic organizations] go to small towns and neighboring villages where no spoken drama has ever been presented, where the peasants and the petty tradesmen see this new type of drama for the first time. It is frequently difficult, at first, for the country folks to understand the significance of the things presented on the stage. It is not always easy to keep order and quiet in the theatres, but generally as the performance goes on the audience becomes absorbed in the story and quiets down. Gradually the listeners grasp the meaning of the simple, educational plays and learn to hiss the villains, applaud the heroic deeds and victories of their own nationals working for the country's salvation, and by slow degrees begin to understand, even though super-

ficially, the meaning of the war that is raging through such an extensive area of the nation.[64]

But the resistance ideology was communicated not just through street plays on the sidewalks or in the teahouses. It found expression in a variety of other cultural forms as well, ranging from drama festivals (such as the unprecedented festival held in Guilin, Guangxi province, organized by Ouyang Yuqian and Tian Han in early 1944)[65] to historical plays with their strong symbols of feminine resistance.

Female Symbols of Resistance: Patriotic Courtesans and Women Warriors

The popularity of the street plays began to ebb in 1939 as the war with Japan entered a new phase of protracted struggle. With the excitement and the uncertainties of the early war years on the decline and more and more dramatists returning to the cities, the demand for a more structured, better staged, well-rehearsed drama increased. Chinese wartime dramas began to move away from pure propaganda to more subtle portrayals of the life of the people and of political intrigue. As a result, multi-act plays, especially ones based on historical themes, replaced simple improvised one-act plays as the most popular kind of spoken drama, especially in urban areas.[66] Historical plays in particular thrived in interior cities like Chongqing and Guilin.

Historical plays (lishiju; also known as costume dramas) did not spring up from nowhere. Their history stretched back to the 1920s, if not earlier. The genre was thus a familiar one, but it now had two new goals: cultivating political symbols in the fight against the Japanese invasion and spreading patriotic messages to a wider audience in the interior as well as in occupied cities like Shanghai. To realize these goals playwrights turned to heroes and heroines from the past. Two such historical figures were Yue Fei, the famed Southern Song general who resisted the invasion of the Jin,[67] and Hua Mulan, the legendary female warrior who donned man's garb to join the army in her ailing father's place.

Among the many ways in which Chinese dramatists sought to galvanize the people against the enemy, perhaps none was more visually appealing than the cultivation and exaltation of female resistance symbols. Symbols, according to Victor Turner, are "dynamic entities, not static cognitive signs"; they are "patterned by events and informed by the passions of human intercourse."[68] Female resistance symbols in wartime historical plays were just such dynamic entities. Designed to

spark political fervor, they served many as examples for emulation. To determine what is new in these symbols, we must trace their origins to an earlier period.

Women's images underwent rapid changes in the 1910s and 1920s. A host of plays focusing on women appeared long before the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, including Guo Moruo's Three Rebellious Women (Sange panni de nüxing, 1926), which depicted the struggle of three legendary women, Zhuo Wenjun, Wang Zhaojun, and Nie Ying, against the constraints of the traditional marriage system; Ouyang Yuqian's Pan Jinlian (1926), describing the courageous love of a frustrated woman; and Song Zhidi's Empress Wu (Wu Zetian, 1937), published on the eve of the war, which sought to rehabilitate the tarnished image of the Tang dynasty female monarch. Of varying quality, many of these plays were marred by crude characterization and unsophisticated plots. Nevertheless, they faithfully exuded the prevailing May Fourth ethos: the fervent pursuit of romantic love and a constant yearning for individual emancipation. The intentions of the authors were clear. Song Zhidi, for example, confessed that his purpose in writing Empress Wu was "to depict women's resistance and struggle against a traditional, feudalistic, male-dominated society."[69] Among these plays, Pan Jinlian was no doubt the most innovative and controversial.

Ouyang Yuqian's Pan Jinlian is based largely on a famous episode in the Ming novel The Water Margin (Shuihu zhuan), later retold and expanded in another Ming novel, Jin Ping Mei. In the original story, Pan Jinlian, after committing adultery with a nouveau riche scoundrel, Ximen Qing, murders her dwarf husband, Wu the Elder. Wu's younger brother, the legendary bandit-hero Wu Song, avenges his brother's death by killing his unfaithful sister-in-law.

Despite superficial similarities, however, Ouyang's five-act play differs markedly from the original episode in both characterization and intention. In sharp contrast to the original Pan Jinlian, a nymphomaniac driven by insatiable sexual appetite and extreme cruelty, Ouyang's heroine is sensitive, passionate, and rebellious. Rather than being evil by nature, she is the victim of a society riddled with moral corruption and personal degeneracy. Her secret liaison with Ximen Qing is prompted more by her disenchantment with Wu Song's refusal to accept her love than by lust. It is also an act of defiance against the oppression of her husband, who behaves like a tyrant at home. Deeply depressed, she finds temporary comfort in the arms of Ximen Qing.

Far from being a traditional, submissive woman caught in domestic

drudgery (in chapter 26 of The Water Margin, Pan Jinlian describes herself as "a crab without legs"), Ouyang's heroine is a modern, liberated woman in steadfast pursuit of romantic love. She is daring and fairly outspoken, lashing out at an unjust society in which women are stifled by inhuman social norms. By contrast, the famous hero-rebel Wu Song is portrayed as a paragon of morality in whom Confucian values maintain their stubborn hold. Though a superhero, he is surprisingly colorless and dull, a man insensitive to tender love and care. There is no doubt that Ouyang's sympathies lie with the heroine. To him, Pan Jinlian is a resolute woman, refusing to be "buried alive" by the oppressive social system.[70] The mere fact that she dares to stand against a decadent system deserves high praise. In the end, she chooses to die at the hand of Wu Song rather than live miserably in a world devoid of love.

Pan Jinlian was a resounding success when it was revised and staged as an opera in 1927. Pan's controversial new image no doubt contributed to the wide acclaim the production enjoyed. Perhaps just as important was the fact that the heroine was played by none other than the author himself. Ouyang Yuqian, one of China's most celebrated female impersonators, dazzled audiences with his remarkable skills.[71] The play became even more popular when the role of Wu Song was taken by an equally renowned actor, Zhou Xinfang (1895–1975), a master in the Southern school of Beijing opera.

The image of a modern, liberated woman seeking self-identity and struggling for genuine love was a marked departure from past depictions of women, who were bound by Confucian norms to an inferior status and forced to live in meek subservience to the male superiors in their families.[72] Moral issues aside, Ouyang Yuqian's Pan Jinlian epitomizes the hopes and frustrations of young Chinese women everywhere in the 1920s.

Women underwent another image change in spoken dramas during the war. As the conflict intensified, plays focusing on heroines appeared in profusion. The portrayal of strong women characters is of course not new in Chinese literature and performing arts. Chinese drama abounds with female warriors and strong-willed women. One notable example is Women Generals of the Yang Family (Yangmen nüjiang; among whom Mu Guiying is the most famous). Other heroines in traditional drama such as Hua Mulan, Liang Hongyu, and Qin Liangyu have also enjoyed enormous popularity.[73] Not surprisingly, many of these well-known characters resurfaced during the war.

Yet wartime plays that featured heroines were distinctive in several

ways. For one thing, a truly extraordinary number of plays appeared in this category during this eight-year war period. Not only were familiar characters like Hua Mulan and Liang Hongyu resurrected, but a host of new names such as Ge Nenniang and Yang E emerged as well. The twin themes of unity of the people and determined resistance against the enemy were stressed in almost every play. And the fact that plays about a single character or event kept reappearing pointed to another feature of Chinese wartime dramas: whatever was recurrent was apt to be significant at a time of national crisis. One more departure from the past was that in these plays, wartime female symbols carried contemporary messages: condemnation of social injustice and a call for equality between the sexes, a continuation of the May Fourth assault against the Confucian tradition. Although wartime spoken dramas touched on a variety of themes, two recurrent subjects stood out: patriotic courtesans and female warriors.

Xia Yan's Sai Jinhua (1936), which appeared on the eve of the Japanese assault on China, was a pioneering work that set the tone for courtesan plays in the war years. Xia Yan based his characters on Zeng Pu's (1872–1935) famous late Qing novel A Flower in a Sinful Sea (Niehai hua), which follows the romance between a zhuangyuan (the highest-ranking examinee in the palace civil service examination), Jin Jun (modeled after Hong Jun [1840–1893]), and a charming courtesan, Fu Caiyun (modeled after Sai Jinhua [1874–1936]).[74] Unlike Zeng Pu's novel, however, which chronicled the long career of Jin Jun and a mosaic of events in various locations both in China and abroad, Xia Yan's play focuses on the legendary relationship between Sai Jinhua and the German field marshal Count von Waldersee, commander-in-chief of the allied occupation forces in Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. It was largely through Sai's efforts and her unusual ties with the German commander, the legend says, that this erstwhile zhuangyuan' s wife saved many lives and forestalled further destruction of Beijing by occupying foreign troops.

In this play, Sai Jinhua is portrayed as a sensitive and kind-hearted woman. Acutely aware of China's impending doom, she openly displays her contempt for a declining government beset with rampant corruption. In act 1 of this seven-act play, when she is accused by an impudent official of defaming her deceased husband's name by returning to Beijing as a courtesan and of disgracing her nation by donning "outlandish dress" and "appearing like a calamity-causing monster in a doomed nation," Sai sarcastically responds: "Sir, I think you are joking. [What you have just said] implies that a nation's ruin is caused en-

tirely by women's dress…. In a city like Beijing, there are simply too many 'monsters.'"

Xia Yan's Sai Jinhua represented a major change in how courtesans were portrayed. Chinese traditional literature, of course, abounds with stories about love affairs between handsome, gifted scholars (caizi) and beautiful, sentimental courtesans. Sai Jinhua, however, stands not for the past but for the present. She is clever, determined, capable of diffusing potentially explosive issues with wit, and, most important, she is intensely patriotic. Sai's behavior, her principles, and her emotions all belong wholly to the ethos and spirit of wartime China.

The play no doubt reflected the author's own bitter disillusionment with the political realities of the time. It is a devastating, if veiled, attack on a government incapable of dealing with the Japanese and on those who were ready to sell out China.[75] "The play was designed," as Xia Yan admitted many years later, "to satirize the government's humiliating foreign policy."[76]

Its polished style and vivid characterization, not to mention its ability to convey a painful sense of immediate reality, made the play an instant success when it debuted in 1936 to rave reviews and widespread public attention. The death of Sai Jinhua in December 1936 added a dramatic conclusion to the story. Needless to say, the play's popularity quickly aroused the suspicion of the GMD government, and it was not long before the play was banned. Xiong Foxi's lesser-known play bearing the same name was also banned, for "exaggerating the positive role of Sai Jinhua."[77]

If Xia Yan's Sai Jinhua reshaped the image of courtesans, Ouyang Yuqian's The Peach Blossom Fan (Taohua shan) gave an even more powerful voice to that persona. The play was originally written in the winter of 1937 as a Beijing opera script; it was subsequently revised as a spoken drama, playing to packed houses in the interior. Again, using the early Qing drama of the same title by Kong Shangren (1648–1718) as his model, Ouyang Yuqian infused his version with contemporary meaning.

The heroine of the play, Li Xiangjun, is a talented young prostitute living in an expensive Nanjing pleasure quarter. She is caught in a bitter struggle between, on the one side, Ming loyalists and gallant generals desperately trying to restore the crumbling Ming court and, on the other, evil advisers and sycophantic ministers who never hesitate to betray their country to the invading Manchus for personal gain. In order to weaken the loyalist Revival Club (an offshoot of the Donglin party, which stood for moral integrity and institutional reforms), the

vicious scholar-official Ruan Dacheng conspires with his follower Yang Wencong, a talented poet and painter who maintains close ties with the Revival Club. The two men contrive to furnish a handsome trousseau to the brothel of Li Xiangjun, the purpose being to arrange a marriage between Hou Chaozong, a leading member of the Revival Club, and the courtesan. As a result, according to their scheme, Ruan and Yang will gain control over Hou.

The plan works. Hou Chaozong and Li Xiangjun happily marry. As a symbol of their love, Hou writes a love poem on Li Xiangjun's fan. In the second act, however, Ruan's secret plot is divulged, and Li, a virtuous woman with high personal integrity, flies into a rage. When news arrives that Ruan Dacheng has ordered the arrest of all Revival Club members because of their persistent refusal to cooperate with him, Li Xiangjun urges her husband to seek refuge in the camp of the loyalist Shi Kefa. Meanwhile, Ruan, together with his superior, Ma Shiying, supports the incapable Prince Fu as emperor in Nanjing. They corrupt the court with force and bribery. In the final act, which takes place in the second year of the new Manchu dynasty, we learn that Li Xiangjun has withdrawn to a nunnery but is anxiously awaiting the return of her husband, about whom she has heard a distressing rumor: that he has surrendered himself to alien rule by accepting an official title. Finally Hou Chaozong knocks at her door. Alas, he confesses that the rumors are indeed true. Li, heartbroken, returns the fan to Hou and commits suicide.

The Peach Blossom Fan must be ranked as one of Ouyang Yuqian's better pieces, in part because its dramatis personae are drawn with such compelling vividness. The play, of course, centers on three principal characters: Yang Wencong, Hou Chaozong, and Li Xiangjun. Yang is what Ouyang Yuqian described as a "double-dealer" (liangmianpai),[78] a man with no integrity and sordid morals who hides a villainous soul under a seemingly gentle demeanor. Straddling the political fence, he is ready to change his position in accordance with rapidly changing political tides. Strictly speaking, Hou Chaozong is no better than Yang. His submission to an alien dynasty marks the hypocritical Confucian scholar with ignobility. Effete and often wavering, he lacks moral direction. Li Xiangjun, exemplifying honor and uprightness, stands in direct contrast to Yang and Hou. She is a woman of enormous strength. Upon discovering that Hou's marriage to her was made possible by Ruan's money, she attacks Ruan, saying, "I would prefer death to wearing a villain's clothes and jewelry" (act 2, scene 1). When she parts with her husband, she asks him not to

worry about her but to take care of himself "for the sake of the nation" (act 2, scene 2). In a confrontation with Ma Shiying, she bitterly accuses him of ruining the country by pillaging the poor and mercilessly killing honest officials (act 3, scene 1). At the end, when her husband succumbs to the new dynasty, she chooses death to show her bitter disappointment in his loss of integrity. In a period of crisis, honor and commitment become all the more precious and important.

Although the denouement in Ouyang Yuqian's play is different from that in Kong Shangren's original version (where both Li Xiangjun and Hou Chaozong enter a Daoist monastery), otherwise Ouyang followed Kong's plot quite faithfully. What is new about Ouyang's work is its message and the immediate relevance of that message to his time. The ruin of a nation, the play seems to suggest, is caused not by the enemy from without, but by the sometimes invisible enemy from within. The play's popularity made "Yang Wencong" into a common scornful epithet in wartime China. "Besides eliminating Ah Q," one writer wrote, "we still have to get rid of 'Yang Wencong.'"[79]

An ideal, patriotic woman, however, must not rely solely on her intellect; she must also maintain her capacity for action. The arrest of Sai Jinhua by her enemies at the conclusion of Xia Yan's play and the tragic end of Li Xiangjun in Ouyang Yuqian's work inevitably carried a dark sense of foreboding about the future. Their protest would be meaningless if no positive outcome were to follow. Thus, in addition to such tragic figures, a positive, hopeful, and forceful image was needed. During the war, a whole array of female warriors were created to serve this purpose, including Ge Nenniang, Yang E, Qin Liangyu, Liang Hongyu, and Hua Mulan.[80] Many versions of the same character appeared as well, indicating the popularity and influence of particular warrior symbols. Hua Mulan and Liang Hongyu, for example, both of whom were drawn from legends as well as from semihistorical sources, share certain outstanding traits: they are gifted in martial skills, exceptionally valorous, loyal, and endowed with charm and grace. And Ge Nenniang, the heroine in A Ying's (Qian Xingcun, 1900–1977) famous four-act play Sorrow for the Fall of the Ming (Mingmo yihen, 1939; also known as Jade Blood Flower [Bixue hua ] and Ge Nenniang), is an interesting combination of the patriotic courtesan and female warrior.

Ge Nenniang, an enthralling beauty who lives in the Nanjing pleasure quarter, was trained in martial skills from childhood. Worrying about the increasing menace from the Manchus in the north, she constantly practices fencing in an attempt "to imitate Liang Hongyu," a

female warrior of the Song who led a successful campaign against the invading Jin army. Ge's skills and courage win her high praise among her friends. "A truly unusual woman," one calls her. When news of the fall of Yangzhou and the tragic death of Shi Kefa reaches Nanjing, Ge Nenniang encourages her lover, Sun Kexian, to join Prince Tang's resistance force in Fujian, where she vows to meet up with him. Later the couple reunites in a defense post in the hills of Zhejiang province. The situation has become even more critical for the Ming. When the Ming general Zheng Zhilong refuses to lend troops to defend against the approaching Manchu forces despite the repeated remonstrances of his loyal son Zheng Chenggong (known to Europeans as Koxinga) and Ge Nenniang, the fall of the Ming seems inevitable. Zheng Zhilong subsequently surrenders to the Manchus. Ge and Sun, however, refuse to capitulate, and together with their troops (composed largely of peasant women) they fight on. In the final act, Ge and Sun are brought before the Manchu commander Boluo after their abortive attempt to break the siege. In an outpouring of wrath, Ge Nenniang condemns the Manchu general and the traitorous Chinese officials for their evil deeds. She slaps Boluo's face when he attempts to take liberties with her. As she is about to be taken out for execution, she bites her tongue and spits the blood on Boluo's face in a last gesture of defiance.[81]

Structurally, little in the plot of Sorrow for the Fall of the Ming could be considered sophisticated by Western standards. Thematically, however, the play communicates an urgent sense of poignancy. Through manipulation of a historical theme, A Ying, like Ouyang Yuqian, filled his pages with powerful nationalistic sentiment. It is a play of patriotism devoted to exposing treacherous officials (Cai Ruheng and Ma Shiying), glorifying the courageous acts of loyal ministers (Sun Kexian and Shi Kefa), and praising the skills and courage of the heroines in the war (Ge Nenniang and her maid Mei Niang). Despite its late Ming setting, Sorrow for the Fall of the Ming clearly plays on modern passions. In lieu of a strong plot and striking events, A Ying placed heavy emphasis on the heroine's character and motives. Like Li Xiangjun, Ge Nenniang is upright and loyal to her country; but unlike Li, who commits suicide in the end, Ge Nenniang goes to her death by execution strong and defiant. Her death represents a tragic fulfillment of her unceasing devotion to her country.

Not only is she patriotic, but Ge is also portrayed as a warrior sensitive to the plight of women. "If men can charge ahead and take enemy positions on the battlefield," she asserts, "women can also defend their nation" (act 1). This acute awareness of women's equality

with men is shared in the play by other female figures such as Lady Tian, Zheng Zhilong's wife. Indeed, equality of the sexes was a recurrent theme in Chinese wartime dramas, echoing an important struggle unleashed during the May Fourth era. For instance, Liang Hongyu, the heroine of Ouyang Yuqian's opera Liang Hongyu, rebuked her conservative husband, Han Shizhong, the famed Southern Song general, when he remarked contemptuously that "women should confine themselves to the kitchen and take care of domestic affairs"; she retorted, "[When a nation is in grave danger] there should be no distinction made between [the duty of] a male and a female" (act 3). In the story, Liang not only displayed her valor by beating the war drum to encourage her soldiers to fight, but she also saved her husband from many military blunders, proving to be the more capable and determined defender of an empire under attack. Such a portrayal of women was certainly consistent with the May Fourth spirit. In general, female characters in wartime spoken dramas demand equality with men. In dignant at being relegated to inferior roles defined by males, they refuse to be mere spectators who applaud men's bravery, or serve only as nurses who tend to the (male) wounded. They are in fact equal participants in the struggle against the aggressors.

Sorrow for the Fall of the Ming was a resounding success when it was first staged in Shanghai's International Settlement in late 1939. It quickly eclipsed all its predecessors in terms of popularity, playing to a packed house for thirty-five days straight and breaking all spoken drama records as the longest-running play in wartime China.[82] This reception was a sign of just how frustrated and enraged people had become over the Japanese invasion. Two years later, A Ying wrote The Story of Yang E (Yang E zhuan), another play set in the Southern Ming. Like Sorrow for the Fall of the Ming, this is a play about a sword-wielding heroine, who attempts to assassinate Wu Sangui (the renegade Ming general who helped the Manchus conquer China) to avenge the death of her husband and the Ming emperor Yongli.

Perhaps no female warrior better exemplifies the spirit of patriotism and resistance than Hua Mulan. The legend of this heroic woman has long been a favorite theme in the Beijing stage repertoire and continues to be popular today. During the war, of course, she was revived numerous times, including by Ouyang Yuqian in the film script Mulan Joins the Army (Mulan congjun). The film, released in 1939, was an instant success, catapulting its leading actress, Chen Yunshang, to stardom. The theme songs of the film also "were heard all over China."[83] Based on a famous ancient ballad, "Poem of Mulan"

(Mulan shi ), by an anonymous writer of the fifth or sixth century A.D. , Ouyang's play, built in turn on his film script, tells the story of a courageous woman who dresses up as a man to join the army in the place of her ailing father. The play, like the movie, was very popular during the war, playing to capacity audiences both in Shanghai and in the interior.[84]

Set in the Tang dynasty, the play opens with a hunting scene in which Hua Mulan demonstrates her superb martial skills by shooting down flying geese with pinpoint accuracy. When the empire is invaded by the northern Turks, the emperor orders a nationwide mobilization to defend the country. Hua Mulan's father, a veteran who is now in failing health, is ordered to rejoin the army. Worried over her father's well-being, Mulan proposes to join the army in his place. Her parents oppose the idea, but she finally persuades them by dressing up convincingly as a man and by demonstrating her unmatched martial ability. For twelve years she fights gallantly, her true identity undetected. Once she and a young army officer, Liu Yuandu, even disguise themselves as Turks to penetrate the enemy's encampment—he as a hunter and she as a woman! In act 6, Mulan foils a traitor's scheme and successfully lifts the siege of a city. She is promoted to major-general after the commander dies of an arrow wound. Upon defeating the enemy, Mulan returns to the capital in triumph. She refuses all the emperor's offers of reward, requesting simply a steed to carry her home. In the final scene, she surprises Liu Yuandu, with whom she has fallen in love, by revealing her true identity as a young maiden. The couple then marry and live happily ever after.

Ouyang Yuqian's play does not follow the original ballad very closely. With a little embellishment and imagination, he reshaped the image of Hua Mulan according to his own wartime vision. The love between Hua Mulan and Liu Yuandu, for example, is a new addition and, as Ouyang explained many years later in his autobiography, not part of his original plan: "I intended to write a tragedy portraying her [Mulan] as a woman fighting against feudalism. But in order to propagate the cause of resistance and to arouse the morale of the people, I stressed instead her courage and wisdom."[85] In the final analysis, Mulan Joins the Army is a disappointing piece. It is flawed by naive characterization and a crude plot, while many of the author's attempts to introduce new themes, such as romantic love, appear to be deliberate contrivances, lacking a sense of authenticity and artistry.

If Ouyang's play falls short of expectations, Zhou Yibai's (1900–1977) Hua Mulan is even less successful as an artistic endeavor. Based

on the same theme but set in the earlier Sui dynasty, Zhou's 1941 play has a different ending. When Hua Mulan discloses her true identity in the imperial court, the notorious Emperor Sui Yangdi, enthralled by her beauty and skill, tries to force her to become his concubine. Adamant in her refusal, she is given a choice between decapitation and submission to the emperor's lechery. In the end, she narrowly escapes death when news about a new rebellion reaches the capital and she is assigned to lead an army to the trouble spot, after which, the emperor promises her, she will be allowed to return to her hometown.[86] This play, too, is marred by the absence of an integrated plot, an awkward conclusion, lifeless characterization, and inept efforts at creating dramatic tension. Critics' responses to Zhou's play were often unenthusiastic.[87]

Nevertheless, both Ouyang Yuqian's Mulan Joins the Army and Zhou Yibai's Hua Mulan captured the attention of Chinese audiences—not for their artistry, but because of the timeliness of their message. Strong anti-Japanese sentiments, presented in the guise of antibarbarian themes, coursed through the two plays, as did loyalty to the nation and filial piety. Both the spirit and the subject matter were wholly contemporary: the perfidy of a traitor (in Ouyang's play, he is a high military officer in Mulan's camp) and the misleading advice of an evil minister (in Zhou's piece, he is the court official Yang Su) were chilly reminders that the most deadly enemies might be lurking in one's own camp. The notion of national unity, a strong theme in both plays, was thus placed in the spotlight.[88]

In wartime China, many Hua Mulan-type heroines appeared. In addition to plays and films, there were numerous cartoons, kuaiban (rhythmic comic talks to the accompaniment of bamboo clappers), and articles about the bold heroine.[89] If Nora symbolized liberated women in the May Fourth era, Hua Mulan effectively symbolized resistance in wartime China. Her strong character, as a symbol, played an important role in both the political and the military struggles against the Japanese.[90]

The female symbols of resistance received further reinforcement in real-life examples. Perhaps Xie Bingying (1906-) best personified the indomitability of Hua Mulan. Born into a gentry family in Hunan, Xie was a rebellious young woman who refused to have her feet bound when she was a child; she later broke tradition by entering a military academy in Wuhan at the age of twenty. Together with a group of women soldiers, she participated in the National Revolutionary Army during the Northern Expedition in 1927, an experience that she later

described vividly in the popular book Army Diary (Congjun riji). Xie was equally active during the War of Resistance. After organizing a women's service corps in her home province, she then went to the Xuzhou front as a war correspondent, filing moving stories about the wounded soldiers and the enemy's atrocities. Her writings subsequently appeared in the books Autobiography of a Woman Soldier (Nübing zizhuan) and Miscellaneous Essays in the Army (Junzhong suibi), among others.[91] No mere flag-waving propaganda pieces about war, Xie's dispatches were often filled with tears and agony. Her genuine feelings and unusual courage won her many admirers across the nation. A lesser-known but equally determined woman was Hu Lanqi (1901-), who helped organize the Shanghai Women Frontline Service Corps in 1937. She visited the front to render medical service as well as to put on patriotic dramas to boost the troops' morale,[92] winning accolades as the "modern-day Hua Mulan."[93]

"Analyses of gender imagery in political rhetoric," suggests Joan Scott, "can reveal a good deal about the intentions of speakers, the appeal of such rhetoric, and the possible nature of its impacts."[94] Indeed, close examination of these female symbols sheds important light on the dynamics of wartime political culture. Although female warriors and patriotic courtesans have long been popular characters in Chinese theater, and although many Hua Mulan plays by intellectuals frustrated with China's inability to defend itself from foreign intrusions appeared in late Qing,[95] never before had such a large number of plays about female resistance fighters appeared. Among over six hundred Chinese plays published during the war, many have titles that mention patriotic courtesans and female warriors specifically.[96] Besides Ouyang Yuqian's and Zhou Yibai's works on Hua Mulan, for example, at least two other plays about this famed woman warrior were published.[97] And three plays dealt with Liang Hongyu.

Why Hua Mulan, Liang Hongyu, and Ge Nenniang? Did women portray the spirit of the resistance better than men? Were there special qualities in these female figures that best symbolized Chinese patriotism? Or were they merely historical accidents? For Chinese intellectuals, drama was seldom an arena for artistic creation per se but more a means of changing society. The female symbols conjured up by these plays were therefore of particular significance, for they reveal much about the political culture of the time. Although of varying aesthetic quality, wartime dramas were never short of patriotic appeal. Yang Cunbin's Qin Liangyu, for instance, a play about the late Ming female general who resisted the Manchu invasion in the north and quelled

peasant rebellions at home, was dedicated "with passion to those intrepid soldiers who defend our motherland."[98] Moreover, patriotic calls were regularly interwoven with strong social ideas. Abandoning traditional, patriarchal conceptions of authority, playwrights placed responsibility for defending the nation on women's shoulders, thus continuing the assault on Confucian values set in motion during the May Fourth era. To cast women of humble social status as heroines was in itself an act of defiance. No longer presented as adoring, obedient complements to peremptory patriarchs, submissive, meek, and lacking in willpower, women were shown to be combative and, more important, to embody the noble ideals of patriotism.

Despite their common struggle against traditional values, the heroines of the wartime spoken drama differed from their May Fourth sisters in two significant ways. First, whereas May Fourth women championed individualism and subjectivism, wartime heroines expounded collective goals and devotion to the nation. Second, and similarly, whereas May Fourth women cherished romantic love and free marriage, the female warriors called loudly for love of country. Priorities were now reversed: instead of personal liberation, saving the nation from the Japanese became the overriding concern. The prevailing mood was to discourage self-interest and personal ambition and to cultivate a collective spirit of self-sacrifice. Resistance became a moral responsibility for every citizen, with personal causes submerged beneath the wave of patriotic fervor.

Female symbols also served the important function of personalization. For even the simplest peasant, war had real, immediate, and personal meaning: death, destruction, loss of home and livelihood were commonplace. The "nation," however, like "popular sovereignty" and "patriotism," is, as Victor Turner puts it, an "imageless concept," unable to "rouse and then channel the energies of the popular masses."[99] In a country overwhelmed by localism and widespread illiteracy, to transform patriotism—love of country—from an imageless concept into a heartfelt emotion was no easy task. If the patriotic resistance struggle could somehow be reduced to human terms, if it could be individualized as a person —a flesh-and-blood human being endowed with authentic feelings and experiences—then powerful nationalistic reactions among the people might be evoked.

The relationship between the play and the audience, as we have seen, was not unidirectional. Audiences were far from passive onlookers. Their ability to understand and identify with the female symbols presented to them, to feel that "she is one of us," was therefore crucial

to the success of the play and to the creation of a sense of common heritage and purpose. For Chinese dramatists, Hua Mulan best personified the spirit they sought to instill in their audiences. As a symbol of loyalty, filial piety, youth, courage, sacrifice, and integrity, she surpassed all others. By presenting this familiar and powerful image, and by portraying her as a patriot, Chinese dramatists appealed to the people to identify their interests with those of the nation. Thus Hua Mulan became a symbolic medium for channeling political ideas, and her wide acceptance in that capacity gave her enormous political significance. As a historical figure, moreover, Hua Mulan also served as a tangible reminder of China's continuing struggle against invaders, providing a crucial element of psychopolitical continuity with the past.

Because a female warrior is more dramatic and striking in appearance than her male counterpart, she can be more effective in cultivating patriotism among the populace. Like the female knights-errant (nüxia) of traditional Chinese fiction, she is gentle, feminine, and blessed with unmatched beauty. Yet she is also brave and upright. Superbly skilled with the sword, she defies death on the battlefield. Her immense courage can easily unnerve the enemy. This juxtaposition of compassionate tenderness and military prowess makes for a most fascinating character. It titillates the audience, evoking a kind of awe and admiration much like that produced by female impersonators in traditional Chinese theater, whose ambiguous sexual identity seemed to bewitch seasoned theatergoers. In creating an effective resistance symbol, Chinese playwrights knew that they needed a character who was both visually attractive and smashingly entertaining. The female warrior's combination of feminine and masculine, coupled with her sexuality and emotional intensity, clearly did the trick.

Perhaps, too, the cultivation of female symbols reflected Chinese playwrights' unconscious assumption that valiant women warriors would shame male spectators, or at least stir traditional male pride, thus inspiring them to act. Another possibility is that the female warrior evinced the playwrights' own yearning for peace and postwar recovery. "There is a tradition," Jean B. Elshtain points out, "that assumes an affinity between women and peace," for they symbolize qualities—nurturance, humility, charity—that rebuff the barbarism of war and underscore social stability.[100]

But to what extent did the selfless, patriotic female symbols in the plays reflect the actual feelings and experiences of women in Chinese society? Did the war facilitate a liberation from economic and political constraints imposed by traditional sex roles? Although considerable

research has been done on the significant role European and American women played during the two world wars,[101] the extent to which Chinese women contributed to the War of Resistance remains unclear. What information there is, however, points to a continued emphasis on the ideal of woman as wife and mother, not as equal partner of man.[102] The dramatists' overt assertions of feminine superiority in wartime plays, therefore, constituted a personal questioning of the existing patriarchal social structure; actual relations between the sexes were not necessarily reflected. Image and reality can be worlds apart. The fact that most of the female warrior plays were written by men makes them to a large extent men's literary idealizations.[103] Even so, that wartime dramas should show women with more latitude in their roles than was permitted in reality is not unprecedented; in the long Chinese literary tradition, women have often been portrayed in a more positive manner than true circumstances would allow, as in the two Qing novels Dream of the Red Chamber (Honglou meng) and Flowers in the Mirror (Jinghua yuan).

The conscious cultivation of symbolic females fighting an occupation force was of course not unique to China. In Vichy France, for example, French resistance fighters and patriotic educators fostered the image of Joan of Arc as a martyr and symbol of national unity in the struggle against the Germans.[104] Like Joan of Arc, Hua Mulan represented the ideal of nationalism, exuding determination and courage to defend her homeland. In wartime China, female warriors like Hua Mulan became the preeminent symbols of resistance. They were the embodiments of loyalty and strength and models for emulation. They exerted a strong influence on the minds and hearts of the Chinese people, providing them with a sense of unity at a time of profound crisis. A popular wartime slogan summed it up like this: "Women must learn from Hua Mulan and Liang Hongyu, and men from Yue Wumu [Yue Fei]."[105]

Historical Plays

Chinese wartime spoken historical dramas were of course not confined to plays about patriotic courtesans and women warriors. A wealth of other kinds of historical plays appeared to meet the voracious demand of theatergoers, touching on similar burning issues of the day—loyalty (for example, Gu Yiqiao's Yue Fei [1940]), internal unity in the face of an external threat (Yang Hansheng's Chronicle of the Heavenly Kingdom [Tianguo chunqiu, 1941]), and patriotism (Guo Moruo's Qu Yuan [1942]), to name just a few. Despite their enormous popularity,

historical plays were not without their problems. What was a historical play (lishiju), after all? How historical were these plays? How effective were they in communicating with an audience and rallying them behind the resistance efforts? Were they better than realist plays (xianshiju) for reflecting the current conflict? These questions aroused passionate debate among wartime playwrights as they searched for an ideal way to blend fact and fiction in their political and artistic work.

During the war many dramatists used the term "historical play" with considerable latitude, and its exact connotation was never clearly defined. This confusion was evident in a lively but chaotic debate on the subject in a panel organized by the respected journal Drama Annals (Xiju chunqiu) in 1942 and involving such leading dramatists as Ouyang Yuqian, Tian Han, and Yu Ling, literary luminaries like Mao Dun, and scholars like Liu Yazi (1887–1958). Ouyang Yuqian first admitted his puzzlement over the nature of historical plays:

In the past, I have edited some traditional plays and written a few spoken dramas. More than ten years ago I wrote Pan Jinlian. Whether this could be called a historical play I am not entirely sure. It was written in the general mood of the time…. Subsequently I wrote a few Beijing operas: Liang Hongyu, The Peach Blossom Fan, and Mulan Joins the Army …. I did not necessarily base my sources on history…. I added a few episodes, for example, to Liang Hongyu. I did the same thing to The Peach Blossom Fan. I hate people who sit on the fence, that's why I portray Yang Wencong in such a way…. I believe that the key to writing historical plays is to grasp the essential mood and issues of the time. As for minor details, we could allow some discrepancies…. [I think] historical plays and history are quite different.[106]

The most important issue about a historical play, it seemed to Ouyang Yuqian, was not whether it followed faithfully events in the past, but whether it served as an effective warning about past mistakes. Tian Han agreed, saying that historical plays served the useful function of "foreseeing the future by reviewing the past," but he also argued that historical truth could add a crucial element of credibility to a play. The more the playwright adhered to historical facts, he added, the more influential a play would become.[107] The novelist Mao Dun, however, expressed doubts about overemphasizing historical reality. Echoing Ouyang Yuqian, he warned of the danger of confusing artistic creation with history. A writer's task was significantly different from a historian's, he said. While a creative writer could dash off compositions on paper as his imagination dictated, a historian had to