Preferred Citation: Frueh, Joanna. Erotic Faculties. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft8199p23v/

| Erotic FacultiesJoanna FruehUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1996 The Regents of the University of California |

For Russell

Preferred Citation: Frueh, Joanna. Erotic Faculties. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft8199p23v/

For Russell

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For good or ill, all the people a person has ever met live within her. Some she must exorcise, while she works to increase the presence, if only partial, of others, who have provided comforts and pleasures, opportunities for loving in everyday life and in work. I thank those providers, who have helped me develop and exercise my erotic faculties: you release the perceived taint of the never entirely exorcised; you are the exorcists.

I think of you in the order in which we came into each other's lives.

Erne and Florence Frueh, my parents, whose love has sustained me all my life

Renée Wood, my sister, whose beauties become stronger to me the older we get

Ida and Sam Pass, my mother's parents, who prophesied my future

Sarah Lewis, my oldest friend, a superb and sensuous cook, a delightful traveling companion and drinking partner, who has, for over half our lives, offered her gracious and tranquil self and home whenever I visit New York

Everett Clarke, without whose teachings my voice and spirit would not have thrived as they do

Claire Prussian, with whom I've shared the best of ladies' lunches, the richest talk about fashion, style, cosmetic surgery, the lightness of intimacy

Edith Altman, mystic sister of unquestioning understanding

Arlene Raven, critic comrade of acid and poetic honesty

Carolee Schneemann, courageous erotic

Thomas Kochheiser, who made it possible for me to write about Hannah Wilke, which I had wanted to do for several years, by asking me to write the catalog essay for his Wilke retrospective in 1989

M. M. Lum, whose stories I love

Peggy Doogan, whose trenchant literacy and nasty humor unclog my heart

The students in the first performance art class I taught, at the University of Arizona, in the fall of 1984: David Flynn, Dawn Fryling, Charles Gute, Nancy Hall Brooks, Willie Hulce, Janet Maier, Dan Mejia, Jim Mousigian, Maureen O'Neill, Pat Riley, Susan Ruff The spell you put on me keeps me charmed

Rachel Rosenthal, so sweet and glamorous

Leila Daw, who shows me the meaning of frenzy, who tells me visions

Kate Rosenbloom, now Anderson, whose laughter and complexion are astonishingly clear

Marla Schorr, who gave me a place to live when I had no home

Russell Dudley, whom I married and who married me out of sanity and pleasure, whose acute criticisms are loving touches, whose photographs enrich Erotic Faculties

Christine Tamblyn, responsive writing and performing partner

Jeff Weiss, whose lush acerbity and relentless integrity have banished the almost unbearable absurdities of academia and the art world

Helen Jones and Steve Foster, who talk with me about ecstasy, perversions, and ruthless compassion

Members of the Research Advisory Board at the University of Nevada, Reno, who, in 1992, granted me a Faculty Research Award to assist in my research on contemporary women artists and aging, work that informs the chapter in this volume on "Polymorphous Perversities: Female Pleasures and the Postmenopausal Artist"

Johanna Burton and Heidie Giannotti, whose backyard is magic

Naomi Schneider and William Murphy, editor and assistant editor at the University of California Press, whose enthusiasm for the unconventional has made Erotic Faculties possible and with whom conversation is erotic

Nola Burger, for the beautiful design of Erotic Faculties

Dore Brown and Jane-Ellen Long, at the University of California Press, for their subtle, elegant, and expert treatment of the manuscript

INTRODUCTION

I was naked and I remember warmth, which was sunlight and my mother. The sunlight touched my skin, which was a threshold for sensation and love. Love and sensation passed into my organs, tissues, fluids, and into the parts of human being that words as definitions only weakly describe, into my soul, heart, intellect. These loci of liminality defined my bodily existence.

I have no recollection of my contour, the discreteness that turns the human body in the human mind into boundary, barrier, and object. I was lying down, as soft as the sheets or blankets that cushioned me and, like me, radiated light. Perhaps the season was winter and the room well heated. Maybe a summer sun caressed my mother's flesh and mine to whitish gold, and the bedclothes and the air as well.

I was an infant and this is my first memory. I began to think about it a few years ago; I do not recall remembering it before that. Since the memory first returned to me, it has come back often, so that I can know it better. I see now that the primary significance of what I call soul-and-mind-inseparable-from-the-body is rooted in my earliest existence, where eros and psyche were wed.

Just as human beings have faculties of speech, sight, and hearing, so we have erotic faculties, which are largely underdeveloped. Erotic faculties enable amatory thought, acts, and activism. The erotic thinker and practitioner may focus on sex, but erotic faculties affect all connections that human beings make with other species and with things invisible and visible. Erotic faculties make possible love's arousal and endurance, which can mend false splits within oneself, such as poet and historian or feminist and motherhater, and within communities whose factions, priorities, and hierarchies work against the meaning of community as mutual interest. Love may sound like a simplistic way to alleviate suffering, but the simplicity of love as an answer to despair and to heartless individualism is a complex project for the human spirit. As a person's erotic faculties develop, so does her lust for living.

Mother-child lust, denied within patriarchy's love of man, is a ground from which erotic faculties develop. The erotophobia embedded in the laws and lusts of the fathers is a misunderstanding of the erotic, for an erotic response to life is not specifically genital but, rather, a state of arousal regarding life's richness. Erotic engagement is bodily, psychic, and intellectual, and a mother can, by loving attentiveness, prevail over the erotophobia that a child experiences as socialization and education subdue erotic desire and (work to) tame it out of her, and that a young scholar reads as subtext in book after book. The authority of scholarly standards crushes erotic faculties and their owner, the erotic, who, if she is lucky and determined, and disciplined in hererotic endeavors, will author herself. The author is the erotic, who is the only authority on her own erotic faculties, which, allowed to thrive, will overgrow the cloister of scholarly etiquette. Erotic authority loosens scholarly writing and lecturing by changing both the conventional form of an academic paper and accepted scholarly costume and oratory. Erotic Faculties makes these changes evident by demonstrating a critical erotics.

The lustful girls and women say

Take me into the bedroom backwards or I will turn you hard

I've got Medusa eyes

If you're as rigid as a rigorous argument

I'll turn you around so hard you may fall down and crumble

I've got erotic eyes

erotic I, she speaks in affirmations

I've got erotic eyes

You haven't lived unless you face us

The standard scholarly voice, of male authority whether used by women or men, has been unitary, flat, dry, and self-censorious. Erotic scholarship is lubricious and undulant, wild, polyvocal, cock- and cuntsure—secure in the erotic potency of bodily particularity unsuppressed by the stereotyped abstractions of age, race, and gender. Cocksure scholarship is not the overbearing sobriety and orderliness of standard academic prose.

To operate as though the human mind speaks to itself and others in only one voice is an ascetic posture. A critical erotics speaks with a sensuous abandonment of intellectual discipline that mortifies the soul-and-mind-inseparable-from-the-body.

An hour before the lecture she was adjusting the sleeves, fitted from shoulder to wrist, of a scarlet dress that bared her knees and shoulders. The light wool jersey skimmed her body. The speaker wore stockings that paled the color of her legs, and black suede slingbacks, with a high heel, that exposed the cleavage of her toes. She examined her face closely, the sparkling gold eyeshadow and black liner, the powder that made the pores on her nose almost invisible and gave her skin a luminous finish. The last touch was lipstick. She outlined her mouth, filled the contours with color that matched her dress, pressed her lips to each other, then to the first page of her lecture.

The rigorous arguments so valued by academies are testimonies to the fact that the thinkers have become stiffs. A rigorous argument may be exact, but the value placed on rigor, the choice of word, indicates the inflexibility of a system that wants to promote itself. Rigor suggests unnecessary austerity, a lifelessness in which the thinker may be in good part dead to the world. In actuality we move through the world and it moves through us. We move each other and are constantly changing. When we're alive to this reality, it moves us, so much that we can't stop moving, and there is no stopping the mind that moves. It is dangerous, and that's a sign of health. The passion of the moving mind sets other minds in motion.[1]

Cock/cunt is moving flesh, full of fluids. To be fluid is to be in love.

I belong to the liquid world of words, I am streaming language, spinning tales, love stories, that go by no single name.

Circum , Latin, around about; scriba , Latin, public writer, scribe. I circumscribe myself. I encircle myself with words. I center myself in intersecting spheres of definition, derivation, rhythm, sound, articulation, interpretation.

Centrality is mobile, and circumference is an illusion.

Words have no boundaries. Users manufacture them, control meaning in the making. Conversation, technical jargon, political speeches, and advertising copy simultaneously circumscribe territories and open them up like poetry, which I see as the most indiscrete genre of writing.

Indiscretion counters the "tight-lipped, joyless austerity" that, according to theorist Terry Eagleton, identifies the work of some male intellectuals. The notable virtue of such scholarship is that it is "unsloppy."[2]

Recently I was told by a man who needed to edit an article of mine that it would be tighter without multiple voices. Keepers of scholarly fitness still uphold rigor and tightness. As feminist theorists have pointed out for more than two decades, Western culture has conceptualized woman as the sloppy sex: she bleeds, fluid oozes from her vagina, she produces milk, and her body is softer than man's. Tight lips don't enjoy the wetness of another mouth, the luscious messiness of saliva .

Be tight, like a vagina that holds onto a penis solely for a man's pleasure. Like a woman who, lusting for a grip on her own ideas, fears her strangeness once she knows what she wants to know, or tries to conceal herself in man's knowledge, and so grasps the phallus.

Wetness is one signal of a woman's lust. Why should she enjoy making dry arguments? Why should her voice defend the phallus? She questions academics' praise of rigorous analyses. Rigor reminds her not of discipline, which can be lust's focus and satisfaction, but of rigor mortis. She does not want to be an intellectual corpse.

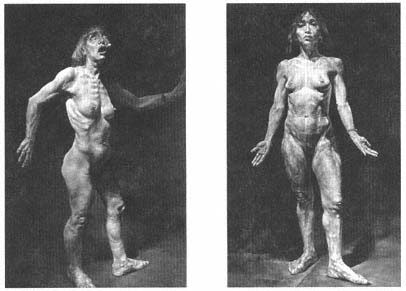

The female body drawn to fit the dimensions of Western art's nude is a diagram of a murder victim. Victim derives from the Latin victima, victim, beast for sacrifice. Bodily specificity is a key element in the performance of erotic faculties. I picture my body's naked beauty and beastliness whether I am more or less exposed. I offer myself to myself; I accept. I am my own erotic object, to touch and to view, to experience life and to act in it. As long as I am an erotic subject, I am not averse to being an erotic object.

The erotic scholar is willing to be sloppy, as sex is sloppy—the movements, the fluids people crave and fear in a time of sexual epidemic—as life is sloppy—full of unexpected untidy events jumbled like puzzle pieces in a box. The erotic scholar understands, too, that sex is elegant—the movements, the satisfaction of desire—and that life is also elegant when intellection puts together the pieces of the puzzle.

Discipline, which is any scholar's job, combines sloppiness and elegance into new terms that balance standard academic rhetorical skills and unconventional means of scholarly persuasion. I use exposition and combine it with rhetorical and methodological techniques that do not appear in standard scholarship and that play with words, ideas, and the form of a scholarly paper. I read a scholar, whose subject was man's loss of virile mission once civilization made unnecessary his hunter role and rituals, who said that playing with language is for children; adults outgrow it. He forgot that play is active pleasure. The erotic scholar would rather pursue a tantalizing idea and incorporate than kill it and turn it into a trophy or some bland food for thought . Narratives are multiple and fragmented, often told in several literary genres and spoken in various voices, such as seer, lover, psychoanalyst, daughter, manlover, womanlover, friend, elder, prophet, fucker, elegist, singer, bleeding heart, activist, patient, goddess, art critic, mythmaker, and storyteller. Graphic and sexual language are paramount. Other techniques include using personal reflection, parody, autobiography, poems, and lyrical language that could be called poetry. Just as the author's identity shifts in erotic scholarship, so does the reader's, for she cannot expect truth to be served to her declaratively. Standard scholarship inhibits a writer's relationship with an audience in the name of objectivity, transparency, and coherence. But elucidation and evocation are not mutually exclusive; elliptical writing is not superficially visionary or utopian, for it conveys the reality of inconclusiveness; and logical evaluation cannot serve as the only means of interpreting thought. In erotic scholarship, poetry and a kaleidoscopic telling disrupt the asinine explicitness of expository prose.

The writer underwent editing.

She used the term biologically determined . The editor, a woman, wrote on the manuscript, "What do you mean by this phrase? Must define yourself."

The writer stated that Hannah Wilke " 'scars' herself with chewing-gum sculptures. Chewed gum twisted in one gesture into a shape that reads as vulva, womb, and tiny wounds marks her face, back, chest, breasts, and fingernails and marks her, too, with pleasure and pain that are not limited to female experience." The editor exclaimed on the manuscript, "That's a lot for one piece of gum! FIX." The scholar thought, "If it didn't do a lot, it wouldn't be art."

I define myself indefinitely .

Erotic Faculties presents poetry as a foundation for theory, and poetry calls into question exposition's claim to authoritative truthtelling. Feminist poets, critics, and scholars have commented on poetry's ability to incorporate daily life, restructure thought, and move readers and hearers to action. Accordingly, poetry is a necessity for women because it distills their experiences, names them, and turns them into knowledge.[3] Poetry defies transparent meaning with rhythm and patterns of sound, so it exceeds exposition's measured explanations of a subject, which guard the reader against bewilderment.

Be wild, ferocious, lascivious, the teacher thinks as she lectures to her class. She says to them, "Don't worry if you're confused. Confusion doesn't necessarily mean that you don't understand, and what you believe is understanding may have little to do with knowledge. Confusion forces you to think, and the process will lead to clarity—for the moment."

Erotic scholarship owes much to feminism, which inspires the erotic scholar's play, which is pleasure, which delegitimizes convention. Loose lips sink ships. I author my eroticism, lust for language and images that convey the interplay of psyche and eros .

Success in scholarship seems to demand conformity. Feminist theorists have written again and again about women's captivity in a language—words, syntax, ideologies, standpoints, rhetoric—invented by men and maintained by male-dominant and masculinist institutions such as the academy. But writing about is not warning against or demonstration of working differently, of writing/thinking/work not as the labor of "must define yourself"—always in someone else's terms. Scholarship is then a

hardship, a labored love, like working diligently at an intimate relationship, which contemporary American society believes is a necessity. With conformity, an art and act of pleasure—writing—turns, unconsciously, into a way to lose and even hate oneself.

Love That Red, the name, I think, of a lipstick color. Love that red of my own lips, dressed not in metaphors of berries or flowers, but in a blast of color that speaks belief in a vibrant voice. The red mouth has been a metaphor for fruits and female genitals and for women's participation in blood mysteries, but I line and color my mouth to exert the autoerotic faculty of speech.

When I was about twenty-five a friend said to me,"You're autoerotic." I loved her saying that but didn't think that my autoeroticism was particularly unusual. I thought everyone we knew was a practicing autoerotic and that younger generations would follow the autoerotic path. Perhaps the sexual revolution led me to believe this. But the sexual revolution was not an erotic revolution.

I see my women students in their twenties losing their minds and bodies to self-hatred as much as my supposedly or superficially autoerotic generation of women did. My students' self-hatred is not an existential condition of women's youth. Young women's self-doubts and low self-esteem continue because "must define yourself" continues, and it extinguishes autoeroticism.

Some feminists' solution to this problem is for women to discover, recognize, and create their own voices. This is exceedingly difficult to do within the proscriptions of academia. Also, women's voices as an oppositional affirmation of otherness, which would celebrate emotion, intuition, delicacy—woman's supposedly natural sensitivities and ways of understanding—is yet another proscription. One of the most important feminist writings on the erotic, Audre Lorde's "Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power," suffers from an assertion of women's sensitivities, which, she says, are naturally invested in the erotic and not the pornographic. Lorde understands that the erotic consists of richness, joy, and profundity in living and that erotic living is socially transformative. That feminists have not developed these ideas of Lorde's as a foundation for a feminist erotics mystifies me. However, for Lorde the erotic signifies tenderness, emotional resonance, and the capacity to love,

whereas the pornographic fragments feeling from doing.[4] I cannot distinguish erotic from pornographic. Words have no boundaries . Pornography originally meant writing about whores.

whore

Me hore < OE < or akin to ON hora < ie base ka- , to like, be fond of, desire > L carus , dear, precious, Latvian kars , lecherous

I desire myself, am the dear one, the pornerotic object for my own delectation, wishing, with lecherous intensity, for the world to be a whorehouse, full of people who define themselves as precious and who know that erotic pleasure need not be delicate.

In your Quest for True Love

You've listened to the lyrics of ten thousand songs

Where words are coupled in

Conventional positions

Like the genders

In the dark

In man's millennia

I've got a mad desire

Look, I'm on fire

With that burning

Undiscerning feeling inside me

Deep inside

My Delta Queen

She was under eighteen

You know what I mean

In your Quest for True Love

You costume me in corsets apricot

And peach, rose and lavender

As if my cunt must be a fruit and flower

Sweetly spiced

I select pearls fresh from my grandma's grave

And silver shoes

In my delirium of living

I do adore myself

As Goddess of the Heart and Hardon

But I am just a beggar

Too bare

For you in simply flesh

How can I repay you for this

Tongue-in-cheek regalia?

For your preservation

Of a few erotic faculties?

For your perseverance in adapting

Any hole to fit your cock?

The next time that I blossom

In your eyes

I will prepare your face

With cherry plum and violet

I will smooth a little color on

Your nipples

I will spray my own cologne

Bellodgia

Fragrant with carnation

Everywhere you'll sweat

When we are fucking

And the next time that you say

I want to fuck your butt your mouth your cunt

I will jam a dildo up your ass

In your Quest for True Love

A critical erotics puts an end to the scholarly tradition of disembodiment. The erotic scholar's lust for the written intimacy of body and mind exceeds personalization of style and any statement of standpoint: I am a forty-eight-year-old white woman, a professor of modern and contemporary art, a performance artist, a wife, a baker, a bodybuilder, a manlover, a womanlover, a daughter of Florence and Erne, sister of Renée, a nonpracticing Jew . Anyone could go on and on trying to make clear from self-identification the embodied circumstances that serve as bases for how and perhaps why she knows what she knows.[5] But embodied scholarship cannot be reduced to what at first seems impossibly complex—all the names one gives oneself. A scholar's concretizing her social location may help the mutual connection between an audience and herself, but erotic scholarship entails speaking from, for, and about the body. The

assertion of an "I" requires more than anecdote and autobiography.[6] I base theory on my body and my experiences and on other women's bodies and experiences. No body, no erotic muscle.

Some of the erotic scholar's powers are urgency, immediacy, mobility, and destabilization, which necessitate speech in as many voices as she can or wishes to use. They develop through lust, necessity, and academic and social training, and they allow a scholar to speak in what may seem like contradictions, at least in the realm of scholarly etiquette. Sexual intimacies and intellect, fiction and art history, anecdote and poetry, high emotion and academic restraint, sentiment and historical facts, empathy and objectivity, friends' words from conversations and theorists' words from books all recur in Erotic Faculties . Erotic scholarship's grounding in various literary genres produces not closed, seamless arguments but, rather, dances with words and ideas that invite readers to join in and invent their own movements in accord with and in contradiction to the author's.

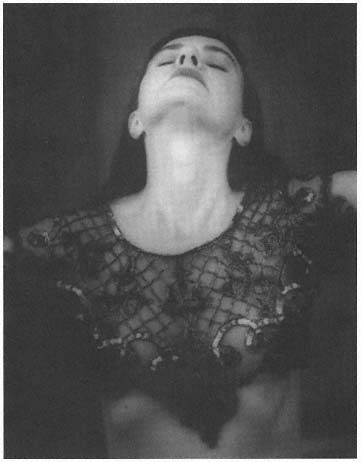

Multiple voices and their apparently contradictory aims and sources may seem to stand together uneasily and to create dissonance. Philosopher Sandra Harding writes that "women subjects and generators of thought . . . exploit the friction, the gap, the dissonance between multiple identities."[7] Unlike Harding, I hear harmony and resonant integrity in multiple voices, and I understand simultaneity rather than gap, and flow rather than friction. Erotic Faculties 's pictures perform by resonating as yet another voice or narrative, to further eroticize an erotic text.

Within herself the erotic scholar does not try to distinguish the poet from the academic or the daughter from the fucker.

Themes, phrases, and images recur throughout Erotic Faculties , as does a drive to approach the edge of sentimentality without falling into a maudlin abyss. Popular culture loves the sentimental, which permeates game, talk, and news shows, Hollywood film, self-help books, checkout counter reading, and hit song charts. Academic culture detests the sentimental, which it deems lacking in rigor and substance, full of romantic flaccidity, the sign of emasculated intelligence or of no intelligence at all, in other words, femininity. Underlying the intellectual dismissal of the sentimental is paternalistic authorities' disgust with woman's sloppiness, and underlying disgust is fear. Although the sentimental is mani-

fested in genres that are masculine—detective novels, rock video, adventure and sports-hero movies—as well as feminine—romance fiction, self-proclaimed New Age seers' go-with-the-flow "slop," gossip columns, and "beauty" advice—femininity prevails in (mis)understandings of the sentimental. The masculine sentimental is (mawkishly) hard-hitting, the popular equivalent of academic rigor, whereas the feminine sentimental yields so much to feeling that it falls apart, into tears.

Fear of tears is fear of erotic connection, the lush and luscious prosaic events, breath, smells, and words that people share. The academy, institutionalized into a body of Dry Eyes, is afraid of ambush by the erotic.

I am the bush, burning so hot that my words redden your ears and eyes. Red eyes are crying, they respond unwittingly, without owner consent, to the interference of emotion, a surprise attack of sentience.

Sentimental strike force, as in love as Mary Magdalene

Maudlin: tearfully sentimental; after Maudlin, Magdalene

(Middle English), often represented with eyes red from weeping

Sentimental, stroking

The strike force slops around outside the bounds of rhetorical protocol

Accused

Of trashiness exaggeration triviality

Of being chatty easy superficial anti-intellectual narcissistic

Intimate and self-indulgent

They call the strike force

Exhibitionists who show off too much heart

Too little head, the Dry Eyes say, is mush and gushy

Moist and gushy, lubricated through and through each cell and sound, the strike force asks, within the vast scheme of eros, which will outlast the rhetoric of cloistered minds, What is the difference between dreck and beauty?

I grew in my father's garden. There I learned the flowery language of lilacs, roses, pansies, honeysuckles, and bleeding hearts. I gathered the red of flowers and my mother's lipsticked mouth, of hearts both whole and broken, of blood between the legs and in the pulse, the wiseblood and the lifeblood that constitute love. Sometimes the bleeding hearts in my father's garden kept me company. Their stalks curved over shaded

soil, under oaks and maples. This dark spot was the place I most liked to sit, nurturing my sorrows as if I had been born into a lonely person's life. I wanted to eat the bleeding hearts, but I simply touched them, resisting out of respect for their delicacy. Their plumpness provoked me to pinch them, but I exercised restraint, caressing each bloom with the whisper, "My beloved bleeding heart."

The dry-eyed scholar sentences herself to callousness. Fashion, formulas for academic success, and dread of being called a moralizer proscribe the sentimental, which women and men can recuperate as a feminine value evolving from erotic authority.[8] As more and more feminists have become academics, they have not intruded radically into male discursive and rhetorical convention. A few notable exceptions are Hélène Cixous, bell hooks, Mary Daly, Arlene Raven, and Trinh T. Minh-ha, but, writing and teaching under the assumed identity of male scholar, most feminist scholars have insufficiently honored or invented differences in methods and expressions for communicating knowledge. The sentimental is an important direction in this regard.

A colleague said about "Rhetoric as Canon," a chapter in this book, "You certainly have the moral high ground." His comment so surprised me that all I could say was, "It never dawned on me that morality was the issue." A person who assumed the moral high ground could only be supercilious, so her sentimentality would be suspect.

A friend in divinity school saw me perform "Pythia," also included here, and said, "That's one of the best sermons I've ever heard." His response thrilled me, because moral activity is erotic.

Sentiment, sentience, sense, and sentence share the Latin root sentire , to feel, perceive, sense. To entirely distinguish intellect from the senses is a mistake. Through intellect a person discriminates and evaluates, but she does so through sense and the senses as well. Sense and the senses are erotic faculties that aid intellection, spawn sentiment(ality), and inspire sentences that seduce the soul-and-mind-inseparable-from-the-body.

Images of hearts and flowers, ancient symbols of love in its emotional, spiritual, and sexual aspects, repeat in Erotic Faculties . Flowers' sensual and aesthetic beauty, their visual intensity, anchors the mind to ideas that

they represent within a particular chapter. So does "golden voice," which appears in discussions of fluency as the ability to speak in the richness of one's own voices. "Holocaust of hearts," "(amazing) grace," "(fear of) flesh that moves," and "soul-inseparable-from-the-body" serve the same anchoring function, and in erotic scholarship catastrophe demands relief of misery, grace joins the physical and the spiritual, and the embrace of flesh that moves lessens erotophobia and misogynistic love, which is really desire for women to be static images of beauty, phallicized wonders who endure a slow death of lifelong femicide in order to deny the terrifying voluptuousness of gravity and time.

Erotic Faculties emphasizes art, sex, and pleasure, especially as they grow out of and affect women's lives. As these subjects intertwine, they create a densely layered picture of ways in which beauty, aging, women's bodies, and sexual practice and experience can influence making, interpreting, analyzing, and theorizing about contemporary art.

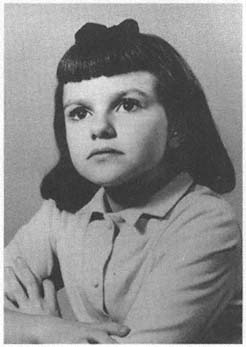

The little girl in the high modern house, sitting at the wooden table sized for her and her sister, very slowly turns the pages in How to Draw the Nude . A nearby shelf holds How to Draw Portraits , How to Draw Animals , How to Draw Trees , but she doesn't spend this kind of time with them. She asks her parents to take down certain books, over and over, from the livingroom shelves, such as a well-illustrated study of Picasso's art and a thin volume with an elegant reproduction of an angel she thinks is her own age. About fifteen years later she discovers that Dante Gabriel Rossetti painted the angel.

She stares for minutes at each picture in How to Draw the Nude , all of the female body, just as she stares not many years later, and on and off for a couple of decades, at Playboy nudes. She feels the nudes in her head and pelvis, in her vagina, desires them and desires herself, and she masturbates sometimes with these images in mind. In the third grade she draws Dora Maar many times. She has drawn the sensual angel too. As a graduate student she writes a dissertation titled "The Rossetti Woman." The nascent erotic scholar thinks about Rossetti's poems and paintings, but it is the latter that attracted her to her subject. She loves the Rossetti woman's large, red mouth, abundant hair, and lush beauty. The scholar's feminism does not interfere with her lust for the Rossetti women or for herself in them.

As a graduate student she becomes conscious of the implications of Picasso's virility: he was a good fucker, and he had imbued his images with brazen sexuality, as only a man can. Her brazen sexuality, alive from before she drew Dora Maar and always strong, could be misread so as to identify her only as a romantic or a good fuck.

She was a good fucker.

The pornerotic body subverts simple romanticism and sexualization, for it smells, smiles, bleeds, and shits, thus living beyond the boundaries of fine art's myths and murders. The pornerotic body plays with the tradition of fetishizing and sentimentalizing the female nude, but creates its own myths through autoeroticism.

In Part One, "Fucking Around," I meddle with the art world's recent veneration of fashionable theory. As the title of the chapter on "Fuck Theory" suggests, I treat theory with playful and erotic disrespect in hopes of asserting an expansive and accessible erotic theory. "Mouth Piece" offers the intimacy and passion of a sexual relationship as a foundation for theorizing female pleasure, and "There Is a Myth" critiques the fucked-up worship of artists and of men's promiscuous sexual prowess, belief in beautiful women's happiness, and confinement of eros to the private domain.

I am sure that my first memory, which I describe at the beginning of this introduction, indicates the regularity of similar experiences in my early life, a condition of warmth that my parents have provided consistently. I consider myself fortunate in this, and such good fortune gives "Fucking Around" and Erotic Faculties in general an optimistic voice that has not suffered from naïveté. Perhaps because of the vivid eroticism that took root in me as an infant, I have always been sexually sophisticated, in wisdom if not in practice. Sex, as acts and thoughts, as matter and energy dynamic, fascinates me and is an intrinsic part of my thinking about pleasure, art, and women. "Fucking Around" presents sexual acts, affection, aggressiveness, and fragility as well as the anguish, delights, and sensations based in knowledge of one's own and other bodies, as ways of grounding a human being's understanding of the world.

"Fucking Around" is not about a search for Great Sex or "the fuck of the century," both of which are figments of the imagination that rob the erotic of possibilities by limiting its focus. Madonna's statement, "I love

my pussy, it is the complete summation of my life," is equally ludicrous.[9] Although women do need to develop genital pride, that is only part of imagining and making real erotic identities that have fucked around with prevailing modes of misogyny: people still think of cunts as stinking, and twenty-year-old women students tell me, unsolicited, that men their age call women who practice casual sex sluts. To fuck around is to discover the promiscuous nature of human identity, whose parts—body and spirit, profession and marital status, age and race, weight and health—people have unconsciously learned to aggressively distinguish from one another, to the detriment of erotic imagination.

Erotic Faculties 's speaking subject could be called heterosexual, especially in "Fuck Theory" and "Mouth Piece." In today's too often oversimplified gender and feminist politics, the response to a woman's desire to be attractive to men and to enjoy sleeping with them can be negative. After I presented a piece not included in Erotic Faculties , a friend who had been in the audience wrote me:

I understand or think I understand from your performance that you like fucking. But I'm not sure how to receive that information. It doesn't excite me. . . Much of my response has to do with being a lesbian in a het-dominated culture and being without much representation in the media. . . . The content of your piece was just too het for me and I'm not sure that that is your responsibility. I just wondered what I was doing there listening to more fuck stories ("more" being that I'm constantly surrounded by the het media). You know, Joanna, all this men and women stuff—it just isn't my area.

I do appreciate the image of you being the aggressive one—the seducer, the controller, the woman in control of her own sexual destiny. I think that is an important idea about your strength and a woman's strength and it is a radical message.[10]

My friend's words are a severe critique that is both legitimate and limited, and they indicate that sexual identification does not have to shut down either understanding or the erotic faculties. Not all heterosexuals submit to some absolute phallocentrism. Kissing a lover's penis is not necessarily any more phallus-worshipping than kissing his back, foot, hair, or nipple. Granted, the penis, like the vulva, is fetishized, but the penis is not the phallus, which is the fathers' law. The fathers' law does not want women to be sexually aggressive or satisfied on their own behalf. A woman's actual or assumed sexual identification does

not designate whether or not she is a lusting subject or a carnal agent. If feminists and women do not seek those erotic identities beneath the names lesbian, heterosexual, and bisexual, which are at once overdetermined and narrow, then feminists and women will colonize themselves.

In an era of sexual epidemic, speaking about sexual pleasure and agency does not have the same liberatory meaning or impetus it did in the late 1960s during the sexual revolution. Today, when multiple partners and casual sex may mean death, they cannot as easily be weapons in a struggle against a repressive society. The idea of an unambiguously oppositional us—the sexual adventurers—and them—the moral regulators—is itself outdated, for, due to feminism, gay liberation, lesbian artists and theorists, women for and against pornography, Foucault, media representation of AIDS, battles over reproductive rights, and other events, individuals, and trends, we see that sexual pleasure exists within a linkage of cultural systems that house and deploy power to manage, indulge, denounce, demean, increase, and circulate sexual pleasure and the representation of sexuality. Nevertheless, the importance for a woman of speaking as a lusting subject and a carnal agent has not diminished, for women have yet to profoundly develop their erotic faculties for themselves through talking about and operating within the discipline of sex.

I am a sexist

I will fight for my sex

I will fight for your sex

For soul-inseparable-from-the-body pleasures

For my history with women and with men

Part Two, "Sustaining Body/Mind/Soul," concentrates on the rockbottom necessity that women know and love their bodies, that they innovate and develop body wisdom as a kind of erotology and sensitize themselves to the erotic as sustenance for human being, as a form of social security. "Sustaining Body/Mind/Soul" also directs attention to relationships and hostilities between women, cultural hatred of the female body, beauty as women's goal and trauma, and the use of female aging in the struggle against social femicide and for transformative practices of femininity and meanings of woman.

People, in public and private, act as if they have an obligation to speak about, indeed critique, other people's bodies. Co-workers, friends,

teachers, actors, the president: no one is immune to the infectious excitement of scrutinizing someone else's fitness and to being the unknown subject of such scrutiny, which encompasses not only muscle tone and (narrow ideas of) beauty but also value as a human being. I could not help but laugh and shake my head when I noticed on 17 June 1994 that President Clinton's "pale legs" revealed by "skimpy jogging shorts" were news yet another time.[11] Pale legs frighten us, and so do ones that are too tan—melanoma—and black—terror of racial difference. We fear variety—of skin color, weight, shape—and we fear skin itself as it shows the condition of long life. We fear flesh that moves, and we have a weak grasp on beauty. Bodies that are not young, strong, and unmarked by scars, veins, and other blemishes—the signs of living and dying—are trashed. Flesh is dirty. As dirty as the earth itself, for flesh belongs to nature as much as to purifying posthuman technologies, but Americans suffer from dirt trauma. The body not only creates shit, it is shit, and when the body disproves the absolute and unerotically imagined contours and finish of a classical sculpture, it loses the grace that fantasy bestows.

A mother and her daughter and son sat in the row behind me on an airplane. He was restless and pissy, and he started looking into the ashtrays, which I notice are generally empty now that airlines prohibit smoking on planes. The mother told the boy not to stick his fingers into the ashtrays, but he obviously kept on, because she let loose with a tirade of dirt trauma: "You don't know what could be in there! It could be a heroin addict's needle, and maybe that addict had AIDS, and you'll get it, too! You would die. And you might stick that needle into your sister. Do you want her to get sick?" The woman went on with permutations of these ideas for minutes. The extent of body-fear astounded me and struck deep. For several moments the entire airplane became a repository of filth that could damage me, and I was stuck in that metal body for at least another half-hour. If the airplane was the embodiment of dirt, then so must be all the world below, where many more people lived to shoot up, fuck, excrete, sneeze, touch their forks to food on restaurant plates and leave it there, and drop into open trash cans and office wastebaskets Kleenex that had caught phlegm from their coughing. The world was a panorama of bodily horror. The body was an oceanic pit.

"Sustaining Body/Mind/Soul" counters dirt trauma, which operates at full magnitude in regard to aging and illness. In "Polymorphous Perversities: Female Pleasures and the Postmenopausal Artist," the old(er) body is shown as erotic, and in "Hannah Wilke: The Assertion of Erotic Will," in which I discuss Hannah Wilke's last art works, I consider the diseased body as an erotic body.

Erotic bodies do not exist in isolation from mind and soul. No body does, and all bodies are erotic when groomed by the sustenance of love. "Has the Body Lost Its Mind?" and "Duel/Duet," which was written with Christine Tamblyn, affirm, in the face of less optimistic and experiential theorizing than mine, that love is a tool for revolution and bears particular significance for women. Erotic scholarship makes love with words and ideas and makes love primary. In male-dominated Western culture women loathe themselves, even in a period of intense feminist activity, for they believe that they are physically flawed and sloppy. In a reshaped erotic economy women's love for themselves would not be the narcissism that isolates them from one another in jealousy and competitiveness. Rather, women would take erotic pleasure in flesh that moves, in fluids their bodies normally excrete, and in polymorphous expressions of beauty.

I am forty-two but I am not middleaged, a word that connotes a fall from grace, from beauty in its many permutations, and I have, here in the flat and humid North, felt embarrassed by my own body and desires, but I have not gotten fat.

I've worn silly slippers, so that the curve of my naked sole could not be kissed, and I have lain in bed all night with a comforter pulled up to my nose, no firm breasts or biceps available to my lover's eyes.

I used to wear tights and tank tops, little skirts over bare legs, feet decorated in anklets and brightly colored high heels.

The dead are covered up, buried.

I think about fruit sweetening and shrinking as it ripens. I think beyond middle age to sweet old ladies, little old ladies. The fall from grace nears completion in the image of a small and cloying female, a shriveling fruit on the way to the garbage.

Our language creates allegiance to the holocaust of hearts.

Back in the desert, I am as naked and as beautiful as ever.

I love this Queen of Eros, my mud-red menopausal blood.[12]

Loveless stories proliferate in the toxic mix of narratives that construct contemporary life.

Local newscasters exhibit Jive-second concern over the latest child abused and killed.

Women students tell me about paternal incest.

Co-workers belittle colleagues' work and deride the appearance of a woman professor who, in their eyes, is not sufficiently pretty to make them feel like men.

In supermarket parking lots men profess the urgency and perfection of their sexual skills to women they have never seen before.

We are pathetic lovers, filled with horror stories, which form a large part of today's mythic superstructure. The author manqué is everywhere, full of erotic energy channeled into perverse sexuality, into ways to fear each other and to be feared.

Most men we've known, a friend half my age and I agreed, do not know how to use their tongues and lips. She and I have more faith in women's oral talents and imagination.

Today's perverse placements of sexual energy are inappropriate, for they are aggressive minimizations of erotic faculties. The horror story is a wonderful genre, because it purges the imagination of banality. But when horror is a staple, sustenance becomes subsistence, and daily life is a form of aversion therapy: the culture will cure you of paranoia, insecurity, and free-floating fear by barraging you with terror.

The author loves stories that romance away the loveless narratives of popular culture and academic discourse. She believes in the alteration of narrative on behalf of love, in people s invention of loving stories, which requires leaping into a narrative and making it yours, locating yourself in the world by authoring yourself into it, purging the soul-inseparable-from-the-body of horror as obsession.

Erotic faculties require the activation of oracular voice, which is developed in Part Three, "Loving Stories."[13] Oracular voice can transform the status quo, which, in Part Three, is the hostile territory of narrative methods and devices that have frustrated and angered me because of their lack of love for flowery language.

Listen to my story, said the Bouquet Scholar. Let us share each other's tongues. Take my story to heart, like a short and necessary kiss. Let it

untie your (k)-n-o-t-s, unwind you from the rules that make your flesh afraid to move. I may be the excited ambiguity of flesh that moves, so unlike a body, numbed by doctrinaire language, that tells the truth of boredom.

Flowery language has so many petals that scholars have been unable to count them all. Flowery language—generative language—is the language of love, a new logos, which is reason—the ability to think—unbound from rigor, which is not exactness but rigidity.

Oracular voice embodies thought as well as feeling, and it enters and lives in other people's bodies, so it is an intimate tool or weapon. The lover's and the prophet's language is oracular voice, a kind of subjunctive that tells what might be and what would happen if. That some people in the present use oracular voice means that what they say in it does not exist only in a utopian future. The struggles, caring, and vision communicated in oracular voice exist in the speaker's present because they exist in her body and mind.

Oracular voice tells what is and what can be done about it.

I am information micromatrix, communications center for the voices of electronic, immune, and ecological systems. To go by different names, to speak in different voices is to be a shapeshifter is to function as a slippage of meaning. The actuality of such fluidity proves that "Love conquers all" is a serious statement. Hate, some say, is love malformed, a skewed disposition of energy and matter that is the opposite of love. The notion that hate is love's antithesis invites easily defined enemies: you're an Arab and I'm a Jew, you're young and I'm old, you're gay and I'm straight. Hate is not love's opposite, but rather a variant, information networks stressed to distress. "Love conquers all" means that love is the implicit order of life, the absolute center of existence.

"Love" and "prophecy" are unacceptable academic and art world vocabulary. Not long ago an artist said to me, "Anything that has too much flesh and love the culture will reject." She said that I could say her work is about love, but I should not say that the love came from her. "My work comes from rage," she said.[14] Intellectuals and artists reject love and prophecy because they depart from the rationalistic thinking that is the cultural establishment's acceptable, respected, and appropriate mode of communication and that is a basis of art historiography. To a large degree, art comes from and communicates in nonrationalistic ways, but the mechanisms of art historiography, which function, too, in art criticism, inform artists' self-presentation: they know that certain vocabulary and explanations are approved.

My face grows flowers of pink and red. My mouth vomits flowers and sucks them in. I am the fucking fuschia arousing rose at the center of your heart. There no mind misconstrues pink as a maudlin color or mistakes rosiness for foolish optimism. A rose is not embarrassed by its color or its beauty.

The rose is rowdy. Flowering voices know Fuck Theory, the pink that was the rose of China Sharon Jericho. This pink is love. In the pink first meant in love, the highest state of health.

Oracular voice does not dwell in apocalypse. While its user may need to speak of catastrophe or cleansing, she focuses on humane ways out of present miseries. Love generates community, our society's common life. While electronic media function as one aspect of common life—a "virtual" community—so do actual speaking, working, and playing among people. Oracular voice is the connection a person as a citizen-lover realizes with other people. Like the original singers of Gregorian chants, the person operating in oracular voice does not perform to an audience but rather delivers on their behalf. Oracular voice, like love, means commitment.

Face me , said the Bouquet Scholar to her listener. When he did, she kissed his mouth; lips turned into rosebuds. The two then spoke in unison. Let my words be the bloom of revolution. Not the round and round of circles that go nowhere, that repeat the same old stories under the veil of overthrow. Let this be the revolution whose axis is the heart.

In "Loving Stories" I embrace the "enemy" of academic rhetoric by articulating its problems, warming up to them by saying, My voice moves at the speed of light, the speed of hearts falling in love. My lips move over my lips. They are moving over your lips, too, making revolution. They say (all our lips together in oracular voice), No word spoken is ever lost. It remains and it vibrates. Love is the answer; revolution is an erotic choice.

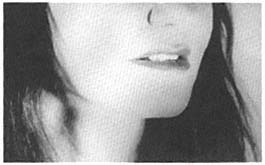

All or part of each chapter in Erotic Faculties I have presented as a performance. The audiences were members of the academic and art worlds, and I specify the location at the beginning of the notes for each chapter. Voice and costume are vehicles for connection. Attentiveness to enunciation, resonance, volume, speed, and silence create a conversational and sometimes hypnotic effect. My voice is strong and soothing, and distinct articulation maximizes the rhythm and melody of words. I am in love with sounds and their movement, and I concentrate on the overall utterance of a piece, which I hear as a complex song.

The force that most fully expressed the conjunction of Frueh's intellect and physicality was her voice. Deep, strong, and melodious, this instrument ultimately entranced her audience. At one moment, its hypnotic richness whispered, even moaned, the secrets shared by lovers; at other times, it passionately decreed that if the critic is courageous enough, criticism and poetics can be the same thing.

Maria Schorr, "Joanna Frueh: 'Jeez Louise,' "

High Performance (Spring 1989): 73

As I note in relevant chapters, in performance I occasionally sing sections of popular and folk songs to which I've changed some of the original or traditional words. Singing and whispering, which I also do infrequently, are startling, but neither they nor other vocal elements are histrionic. My desire as an erotic scholar is to let words enter an audience without intrusive theatricality, for the voice is an erotic tool that enters bodies and works in them organically.

Her articulation of each word seemed supernaturally clear to the speaker as she turned over a page of text with a movement so graceful that the paper fell from her fingers like a satin scarf. Then she imagined her voice flowing from her mouth like a river or shining like a shaft of light that could project to other planets. She wanted to touch every inch of her skin, but she could not, for she was reeling. Part of her existed only with the words she spoke, and they were carrying her away with them.

Without being overtly sexy the voice can be profoundly charming, and the more a speaker can modulate that seductiveness, the more her words and ideas will affect an audience. This is true whether the style of speaking recalls oratory in front of a large audience, intimate conversation with a friend, lecturing to a class, or sex talk with a lover.

The performances are visually minimalist so as not to obtrude, because the words are paramount. I generally stand at a podium, as for a standard academic lecture.

Costume is important because it makes clear the unity of intellect and body and it reveals the body's simultaneous strength and vulnerability.

Although small in stature, her years of bodybuilding are evident in the sensuous lines of her body. Her black, pink, and white costume

echoed the colors of Bourgeois's marble and connected the power and vulnerability of both women.

Maria Schorr, "Joanna Frueh: 'Jeez Louise,' "

High Performance (Spring 1989): 72–73

My dress reveals upper body development and the speaker's flesh. An academic's costume, like many professionals' costumes, is a protective covering that armors a lecturer in the authority and power appropriate to her profession. I costume myself in different powers, which arouse the erotic faculties. As I said near the beginning of this introduction, erotic faculties enable amatory thought. My intention is not to attract an audience sexually but to charge an atmosphere erotically so that it, like a voice, can enter people.

The clothing is obviously wrong for a standard scholarly lecture. I've worn a white-leather, strapless minidress and red high heels ("Mouth Piece"), a red leopard-print unitard ("Duel/Duet"), and a black spandex minidress with a print of large roses predominantly white and magenta ("Fuck Theory"). Some or all of the clothing is form-fitting, and the colors black, red, pink, and white repeat, generally in solids. The colors frequently relate directly to images in the texts. A long poem in "Mouth Piece" is structured, in part, by the colors white, red, and black. (My hair is almost black.)

Frueh, dressed in this delicately detailed tux, appeared like a vision [out] of Romaine Brooks's portraiture.

Elise La Rose, "Vampiric Strategies,"

Dialogue (September/October 1990): 25

Frueh was her own best ad with her generous yet sleek weight-lifter's body.

Nancy Martell, "Christine Tamblyn/Joanna Frueh,"

P-FORM (January/February 1990): 23

I have worn a straight skirt and a jacket with a silk or satin camisole underneath. After I'm introduced or early in the presentation I take off the jacket. This gesture, or the audience's looking at skintight lycra or white leather, casts me as a spectacle that could easily be labeled "sex object," attractive according to masculine desire. But the erotic body is a voice that conveys rhythms, ideas, and sensuousness particular to

an individual and not modeled by masculine standards. My intention is to convert formulaic erotic language and symbols into a foundation for erotic expansion. So I present myself as familiar erotic terrain but quickly convert it through words, ideas, and the particularities of my bodily gestures and vocal modulations into an erotic relation that turns an object into a subject who speaks and fucks in her own voice. That is a position of autoerotic and relational power, and although the images of myself I create have a stark and alluring aesthetic impact, it diminishes quickly and normalizes so that appearance does not distract an audience and body remains as an integral element of an audience's intellection.

An hour is a long time to listen to text being read, a long time to sit in a theater with no visual stimulation beyond the contrast of dark hair, white leather, and red lipstick. But Frueh's presence is compelling.

Michele Rabkin, "Joanna Frueh,"

New Art Examiner (May 1989): 60

Stage direction and pictures in Erotic Faculties help to evoke that "compelling" presence, which is sensual and commanding, dynamic and embracing. They establish a flavor. The stage directions are not absolute elements of performance but, rather, indications of what has happened or what might happen, how performing a particular section of a piece has felt or how it might feel.

The speaker looks as intently at her audience as they look at her. This mutuality, this spectacle of self-consciousness is a game that lovers play, trying, whether they know it or not, to expand their erotic faculties. The lover's behavior and identity are multiple and complex. She cannot confine them to a sexual relationship, for within that constraint the erotic faculties wither. Speaker with audience, writer with reader: these are erotic relationships. The erotic scholar is a lover.

Demento Beauty, here I am

Get out of my way or I'll have to slam

Your smug little ugly little custardy face

What makes you think you're part of the human race?

CHORUS:

I'm so beautiful so berserk

Why doesn't someone pay me so I don't have to work?

My pearlpink skin my diamondshine eyes

Miss America, move over, I'm the maniac prize

You think you're a gift to the family of man

You're a chopped up melody an also-ran

The hasbeen who climaxed before being born

If I had compassion you'd be forlorn

Demento Beauty walked the street

Ran down an alley tripped on the feet

Of a dirty condition a city of slime

Is it a corpse or a wino or just a crime?

Rape in the morning rape in the night

Look out sweet ladies or you might have to fight

The sap with integrity the guy with a gun

Who thanks you for indignities after they're done

Pull out your razorblades reach for your knives

Women of distinction buttersoft wives

Listen to the language of those hips that sway

It's Demento Beauty leading the way

I charge over bodies my arms held high

No flagwaving soldiers no apple pie

Just homemade weapons that make men twitch

The flamingo pink mouth with the tongue of a bitch

Demento Beauty, I'm so pure

Nobody's honey but I've got allure

Electro nuclear solar zap

Some say I'm magic some say a trap

CHORUS:

I'm so beautiful so berserk

Why doesn't someone pay me so I don't have to work?

My pearlpink skin my diamondshine eyes

Miss America, move over, I'm the maniac price

PART ONE—

FUCKING AROUND

Fuck Theory

"Fuck Theory" is a revision of a performance with the same title that was delivered on the panel "Postmodernism in the Classroom: What Are We Talking About?" Society for Photographic Education Conference, Washington, D.C., March 1992.

[Frueh stands at the podium in a lycra minidress that bares her shoulders, arms, and chest. The dress is patterned with large roses on a black ground. Her lips are rose red. ]

The teacher liked to fuck around. She played with bodies of ideas, which she called philosophies of seduction, and with the palpitations of language. "My voice," she said to her students, "enters you as I speak, your breath and breathing fill this room, our time together. Today," she continued, "bound, wracked, and shattered hearts disturb the oblivion of Everywo/man's dreams. This is the holocaust of hearts, where the birth of fluency is daring to speak in a voice that is your own."

One of the students said to her, "You teach erotically." She took this as a great compliment but could not put her finger on the reasons for the student's statement.

The teacher, in the flesh, embodies knowledge.

The proliferation of theory has marked the art world since the early 1980s and has become one of its dominant postmodern characteristics. Many aspects of theory and its domination have irritated and disturbed me. Responsibility for a postmodern set of cans and cannots that have colored understandings of artists, art works, and art-critical writing does not necessarily lie with key figures such as Derrida, Foucault, and Baudrillard but, rather, with followers who have turned the fascinating and useful writings of father figures of speech into cant and canon. Ironically, sacred text degrades into schlock theory. Trickledown mouthings are antithetical to the relativism and eclecticism that typify postmodern thinking.

Mouthings may be sexy, but they are not erotic, for they cannot kiss a reader's or listener's soul; they are close-lipped, a fashionable attractiveness that arouses imitation. Because mouthings fail to translate ideas into the speaker's or writer's own tongue, they lack the verbal liveliness whose aesthetic configuration depends on the erotic as foundation. Fashion entrepreneur Karl Lagerfeld said, "No design, no desire."[1] This was a statement about the poor sales of American cars, but I want to give it a loving translation: style—a distinctiveness that deviates from the cant of fashionableness and that exists at one with content—manifests the erotic.

My teacher sat in front of the class smoking a cigarette and lecturing on nineteenth-century painting. Her miniskirt uncovered black fishnet stockings on crossed legs, her deep laugh spread her lipsticked mouth into a sybaritic smile, and her black hair waved witchily along paler than cream cheeks. Her dark voice slipped into my mouth and down my throat, rested on my pelvic floor and in my heart, and flashed to my extremities. With her ideas inside me, I could learn to speak perhaps as clearly as her body spoke to me.

I was in college. My teacher was Carol Duncan, a Marxist art historian with a heart on fire. She was pleasure in pedagogy.

The heart on fire is the attribute of the Renaissance Venus. Love burns in the holocaust of hearts. It can burn up or it can burn on.

I say the heart and mind are one, and the flaming heart is the intellect fired in eroticism, the intellectual who enfleshes ideas, screws around with them and makes thought voluptuous.

Baudrillard writes in "Design and Environment, Or How Political Economy Escalates into Cyberblitz" that "the great referent Nature, is dead, replaced by environment, . . . [which] designates . . . that from which one is separated; it designates the end of the proximate world." His discussion transformed my thinking about environment, but he did not lead me, in that article, to think that nature is dead. He says, "To speak of ecology is to attest to the death and total abstraction of nature" and writes, two lines later, of the "gradual destruction of nature (as vital and as ideal reference)."[2]

Several years ago I heard a photographer, in a lecture about her work, say that nature doesn't exist. In the past decade I've encountered that idea so many times in art-world wordings, often derived from Baudrillard's ideas, that I cannot cite or even remember them all. The photographer then said that only the artificial was approachable, like a golf course or a national park. I know that nature, as a word and as many ideas, is a product of the human mind; and I also know that mountains, cactuses, desert, and sunset exist. They could be seen outside the building where the photographer spoke in Tucson.

Cant demeans the reality of personal experience, which is not necessarily innocent, romantic, or devoid of intellectual astuteness.

I stood on top of a mesa and the wind said, Be my daughter or I'll blow you over the edge.

My mother saw a buck leap over the backyard fence last summer. Deer were once exotica, sights to see on family travels in Vancouver, Maine, Colorado. The strange and the familiar forever conflate, and now deer menace the garden in my parents' suburban home north of Chicago.

Last July, in my own home in Nevada, underground rumbling woke me at 4:00 A.M. Later that day I expected news reports of an earthquake or a bomb test. I asked people if they'd felt what I had. I found no confirmation.

Neither did Russell and I after he pushed me out of bed in a panic in the middle of the night when he saw a huge snake where our pillows met.

Immediate experience with spirits who embody the land is primary in some work by Southwest American Indian women writers: Lucy Tapahonso's story, "The Snake-man," updates Big Snake-man in the Navajo Beauty Way.

Nature as the great referent resonates. It figures in many contemporary stories and shifts shape according to the teller.

Nature includes the speed of light; the interactions of plants and women in the curandera, who appears as a character in Hispanic and Chicano Southwestern women's writing; the elements in plants that benefit human health and beauty; the name of a legendary stripper, Tempest Storm; the idea that, as theorist Donna Haraway says, "Our best machines are made of sunshine; they are all light and clean because they are nothing but signals, electromagnetic waves, a section of the spectrum . . . [and the] engineers [of such machines] are sun-worshippers"; the fact that the Earthquake is the name of a radio station in the San Francisco area; the techno-organism of human being and computer; my mother telling my father to cut back the dying honeysuckle on an ungardened part of their property and Dad exclaiming, "What do you mean? This is a forest!"; the Southwestern American Indian cultures understanding that sexuality and wilderness are the same.[3]

I saw a stick and it looked like a lizard. I saw a lizard and it looked like a leaf. I heard a rattler sound like a cricket. I saw a snake and it was a snake.

Things are not what they seem, for nothing is singly itself. Do not call this phenomenon the synthesis of dialectics. Call it love. Lovers know Fuck Theory.

Comet cleanser smells like cum, hawthorn blossoms smell like cunt, and evergreens, in a particular intermingling of light, humidity, and temperature, smell like human urine.

I smell. The verb is transitive and intransitive. I smell a rose. I stink.

I reek of rose. Flowery sounds enter you as I speak, my body blossoms within yours. I am Fuck Theory, the heat of the sun, the intellect alert in nerves, flesh, blood, and water, as it seduces the scent out of matter. That scent is the breath that carries a golden voice from rose and crotch and mosques whose mortar was mixed with attar of rose so that when the sun shone, the building became perfumed.

[As Frueh speaks she hears an uncanny clarity in her voice. It is so acute and affectionate that it penetrates listeners' bones while demanding nothing. ]

In my reeking rosiness I like to wear full skirts so I can take long quick strides as though I'm walking away from the damned; and I also think that maybe I'm one of the damned and that's why I'm walking so fast.

To be good and evil is to be in between, in movement, and to be outside them altogether, to cross into them from other conditions. Crossing is the law of laws. Crossing is love, which excludes no one, nothing. Fuck Theory loves all positions.

The technical language of postmodern theory became an exclusionary weapon, a tool of mastery over art-world money-, star-, and idea-making. This situation was replete with irony, for schlock theory mouths an end to mastery. Words such as sign , code , text , discourse , problematic , privilege , male gaze , phallic mother , hegemony , praxis , fetish commodity , and many more have come to be part of the unloving tongue of schlock theory. Technical fields have technical languages, art being no exception, and key figures speak a magic language that transforms, on the tongues of charmed followers, into prosaic jargon that, despite its tediousness, belongs to a postmodern arcanum whose very arcaneness has been spell-binding.

Arcane language holds schlock theorists in thrall, and they make mental masturbation into the Postmodern Mysteries. Erotic thinking is also mental masturbation, the voluptuary's enjoyment of her own insatiable intellect. Erotic thinking, unlike Postmodern Mysteries, desires connection beyond the arcane legitimacy of a limited self-love. The erotic thinker is a fucker.

Years after her student said, "You teach erotically," the teacher could finally say to herself, "Now I can put my finger on the reasons for the compliment. I finger ideas the way I finger my own clit and lovers' hair. I fuck myself in public when I speak, I put my fingers on listeners' parted lips to learn better, each time I touch an organ other than my own, the fingerings of flesh that produce the clearest and most subtle fluencies. With my hand on my heart, I offer no finishing touches."

The teacher remembered a long-gone sex partner who had said to her, after she performed fellatio for a few minutes then hesitated for fear of having cum in her mouth, "Get your mouth off my dick and look at me. I'll do myself." She had cringed under his narcissistic hostility, which killed her loving tongue for him forever.

Other memories came:

The Mormon, a teacher too, who said, "Teaching is being, not information."

The psychic who said, "'Love conquers all' is no laughing matter. You give your students unconditional love."

I use the word love to designate certain phenomena, the fluent and stuttering connections of invisible relations among people, Tvs, waters, angels, animals, antibodies, radios, deities, plants, and bodhisattvas. Love is the ultimate phenomenon, the spinal cord and spiral dance of magic, physics, spirituality, mathematics, and psychology. Love is the heart of the seemingly dismembered body of reality, for love incorporates all positions.

Love is the common ground. There nothing is a law unto itself. There human flesh is indiscrete, not boundary, barrier, or object. There a listener hears the words threshold , indeterminacy , fluctuation , multiplicity , contingency , and in-betweenness , liminal , fluidity , permeability , and vulnerable as sounds whose movement holds together sky, earth, and water in their particular configuration; joins people in sex, romance, and familial and national ties; enfolds the conscious and unconscious functions of the mind; links human and computer minds in cyberspace; keeps your blood from spilling out of your pores; creates inescapable fields of gravity light-years away; and rotates the earth on its axis.

Love makes the world go round.

I learn to dribble honey

(A moment is not absolute)

Gold starts sticking to my lips

(A century is a moment in history)

As I search for golden tongues, I meet the '49ers' gold fever, the conquistadors' greed, and Jason stealing the golden fleece. I see yellowing pages that say, "Obey the Golden Rule: do unto others as you would have others do unto you.

Our kiss lasts only a moment

Fluency is one golden moment

The unloving tongue of Postmodern Mysteries diminishes thinking that does not fit the self-made masters' constructions of reality. David Joselit's critique of Carolee Schneemann's slide installation, Cycladic Imprints , in San Francisco MOMA'S 1991 The Projected Image exemplifies such distortions.

In light of recent feminist theory, which understands femininity as a constantly shifting and transformable set of characteristics, Cycladic Imprints appears somewhat naive. In its dependence on supposedly timeless symbols of the female body—the violin, fertility figures, the vagina itself—Schneemann's work seems to assert that femininity is something timeless and unchanging and based on the body alone.[4]

For Joselit, Schneemann's work does not meet the social-construction-of-the-body criterion of complexity and sophistication wrought by fashionable theory. When someone does not use or refer to that obedience-demanding cant, she "appears somewhat naive." Naïveté, however, may reside in the dissolution of carnal knowing—wisdom that develops through enfleshed ideas—into displacements of the body by postmodern mouthings.[5]

Recently I talked with Carol Duncan, and much of our conversation centered on postmodern theory. She called it a radical orthodoxy. I think of postmodern cant as an amazing gracelessness.

I listen for golden voices and amazing grace. I stammer, tell only parts of stories, as any storyteller does. I am listening for self-love that cancels cant, which is the thriving sickness of self-erasure.

I look more like a whore as I grow older, act the age of ancient Graces, the sacred charismatics who gave charity as sex, compassion, kindness, all the faiths and hopes that countered culture at its worst and brought to life pornography as dirty as the earth itself.

Dying dictionaries say too simply that pornography is writing about whores. New scholars speak new meanings. They say, Pornographic partners know Fuck Theory, the powers of true love.

[Frueh returns to the panelists' table and takes her place among them. ]

Mouth Piece

"Mouth Piece" has been performed at:

Columbia College Dance Center, Chicago, Illinois, February 1989

Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania, November 1990

Massachusetts College of Art, Boston, Massachusetts, February 1992

The LAB, San Francisco, California, January 1993

Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, February 1994

An excerpt from "Mouth Piece" was published in P-FORM (Winter 1991) and is reprinted by permission of P-FORM.

[A black folding chair and music and mike stands sit upstage center. The music stands hold the script. Frueh enters, wearing a white-leather, strapless minidress, bright red high heels, and scarlet lipstick. The heels click slowly on the floor. She walks downstage center and speaks unmiked, her back to the audience. ]

When I was twenty-five, I began voice lessons. My teacher's name was Everett. Everhart, strong as a wild boar, your voice was rich and mellow. You had control and power, authority and beauty, seductiveness and compassion, a heart that came from the diaphragm, source of the column of breath that rises from the gut, from the vital organs, of which the mouth is one.

The mouth, your voice said to me, is the exit from the body and the entry to the world, the opening at which the inner and the outer breath are one and private and public air can mix.

Everett gave me satin dresses, red and white and black, bought at mansion sales. I was to perform in the gowns, for Everett wanted me to be a singer, a chanteuse, creating heat with torch songs.

On the night of his sixtieth birthday, Everett came to hear me at a club. He said my singing was the best gift he could receive.

Once, early on, he told me, "You have a golden voice."

Sometime later, I said, "I want to be a star."

He said, "You will be."

Not long after that, Everett became ill and lessons were canceled week after week. When he began teaching again, I did not return. Another of his students told me, "Everett's asking about you. You' re like a daughter to him." Still I did not return.

Everett, Everhart, the next time I heard about you, from a student, she told me you had died. Someone, a disgruntled lover, it was said, had knifed you in your studio, where you had moved my voice to sing and speak in ways I had not known before.

[Frueh turns and faces the audience. From now on she alternates between standing and speaking miked and sitting and speaking unmiked.

Standing, miked. ]

Mouthpiece:

One who speaks on behalf of others; one who expresses another's sentiments and opinions; one who gives public circulation to the common soul.

Mouthpiece:

Something to put in the mouth. That part of a musical instrument which is placed between the lips and is usually made of a material agreeable to the mouth.

Mouthpiece:

An instrument in which the vibration of membranes sends forth harmonies that scholars throughout the ages have been unable to reduce into components and have therefore named aesthetics and poetics. Examples include wood wind and flesh cock.

Wood wind and flesh cock speak. They announce, proclaim, both by sensation.

I speak in public.

Seas and rivers, desert prairie speak. They reverberate, emit the sounds that scholars cannot categorize.

I speak in private.

Baying hounds give tongue and firearms report.

I speak on, against, and for.

Speak: to exercise the voice; to loosen discourse; to deliver an address in an assembly; to disclose, reveal; to appeal to, touch, affect, or influence.

I speak to desires.

I am on speaking terms with you.

[Frueh looks directly into an audience member's eyes. ]

I speak for those of you who don't yet know the words, who've lost your tongues, who have not found your voice, who are afraid to tell your stories, fearful they may be too telling.

I will be your mouth, speak out, so as to be heard distinctly.

I will speak up, testify to acts, emotions that exist in speechlessness because belief calls them unspeakable.

I just wanna testify 'bout the love you give to me, and so I have a foul mouth, trash mouth, big mouth for speaking on the streets and in the bedrooms.

With my big mouth I can eat your heart, swallow your pride, devour you if I desire.

With my big mouth I speak in blood and shit, in cum, saliva, and orgasm, in wisdom gained through books and body.

And it was written that He was excruciatingly close to coming. "And then He came," She said. "For I drew out His semen, warm and slow, and I tasted His orgasm, I took Him wholly into Me, into the body of the world."

I speak with a learned tongue, for I am the Spokeswoman, Woman-Who-Speaks.

Belief that the feminine nature could be coarsened by learning has been coupled in history with the idea that it is in woman's nature to say too much.