II—

Latin Manuscripts of the Speculum

Compiled at the beginning of the fourteenth century for the use of preaching monks and clerics, the Speculum humanæ salvationis was a widely used volume in the late Middle Ages. There exist today more than 350 manuscripts in Latin and translations into Dutch, French, German, English, and Czech.[1] Copies were made in religious houses, convents of all orders, as well as by lay scribes. Toward the end of the fifteenth century there was hardly a library in northern Europe that did not possess an example. Like the majority of religious texts of the time, the Speculum was a compilation made primarily from commentaries on and adaptations of the Bible. Almost all copies are illustrated, following the pattern of the manuscripts dated 1324, made from one which is presumably lost. In the Prologue is the statement that the learned can find information from the scriptures, but the unlearned must be taught by pictures, which are the books of the lay people.[2]

The text and pictures of the Speculum are devoted to the interpretation of the New Testament through prefigurations in the Old, the so-called typological system, which was the medieval way of relating the Old Testament to the life of Jesus Christ. Originating in Asia Minor with the Greek Fathers, it passed into Western thought and was greatly spread by the influence of St. Augustine.[3]

Typology appears in the writings of many medieval religious scholars and notably in the Biblia pauperum , written in the late thirteenth century, which contained in words and pictures

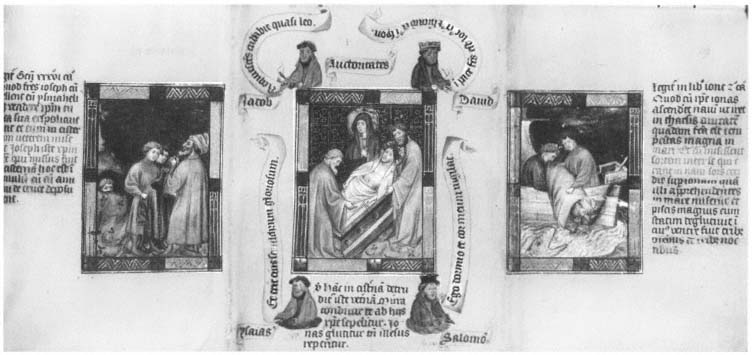

II-1.

Jacob Laments His Son Joseph.

Christ Placed in the Sarcophagus.

Jonah Thrown to the Whale.

Biblia pauperum . c.1400.

British Library, London, Kings Ms. 5.

a succinct interpretation of the Bible. To the medieval theologian every event in the Gospels had been announced in advance. For example, the entombment of Jesus was prefigured in the casting of Joseph into the well by his jealous brothers, and Jonah thrown into the sea and swallowed by the whale (fig. II-1).

The commentaries on the Bible were, in practice, as important as the scriptures themselves. The Church had never specifically recommended the reading of the Bible to the faithful, for a book so full of enigmas could be understood only with the help of the writings of the Fathers of the Church.[4] The major sources of the Speculum were the Historia scholastica of Petrus Comestor, the Legenda aurea of Jacobus de Voragine, the Antiquitate Judaica of Flavius Josephus, and the works of St. Thomas Aquinas.[5] Many of the events are drawn from the books of the Apocrypha, most of which were accepted parts of the Bible until their rejection by the Puritans in the seventeenth century as not originating in the Hebrew text. Later editions of the King James version and many modern Bibles omit the Apocryphal books.

The two chapters with which the Speculum begins, and which precede the chapters with Old Testament prefigurations, describe the Fall of Lucifer and his accomplices from Heaven into Hell, the Creation of Eve, the Admonition of God not to eat of the tree of the knowledge of

good and evil (sometimes interpreted as God uniting Adam and Eve in marriage), the Temptation, the Fall and Expulsion, and finally the Deluge, which ended the first age of the world according to medieval historiographers.

These are the events on which is based the doctrine of Redemption by the Savior. They have no prefigurations. Medieval authors also held that mankind was not saved from damnation by Christ alone but also by the life of the Virgin Mary, the associate of Christ in Redemption. That is why the account of the Redemption begins, in Chapter III of the Speculum , not with the Annunciation to Mary, but with the Annunciation to Joachim of the conception of the Holy Virgin Mary by his wife, Anna. One finds in the Speculum certain aspects of Catholicism which were contested during the Reformation, among them the Mariolatry which pervades the book and culminates in the last two chapters, XLIV and XLV, devoted to the Seven Sorrows and the Seven Joys of Mary.

As noted above, the Speculum was written sometime before 1324, the date which appears in two manuscripts in Paris (Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. lat. 9584, and Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Ms. lat. 593). The Prohemium in each copy opens with the following lines, with the Latin contractions spelled out:

Incipit prohemium cuiusdam nove compilationis edite sub anno domini millesimo ccc 24 nomen vero authoris humilitate siletur. Sed titulus sive nomen operis est speculum humane salvationis.

(Here begins the prohemium of a new compilation published in the year of our Lord one thousand three hundred twenty-four although the name of the author is unstated out of humility. But the title or name of the work is Speculum humanæ salvationis).

It seems very probable that the reference to the anonymity of the author, because of his humility, was in his original manuscript.[6]

Line fifty-three, Chapter XXVIII of the Speculum states, dicitur enim quod ubi est Papa ibi est Romana curia . This could only have been written during the so-called "Babylonian Captivity" when the papal court was in Avignon (1309–1378). It follows that the manuscript must have been written between 1309 and 1324.

The authorship of the Speculum has been variously attributed to Conradus of Altzheim,[7] to Vincent of Beauvais,[8] to Henricus Suso,[9] and in the extensive work of Lutz and Perdrizet, to Ludolphus of Saxony.[10] There is also an inscription in a fifteenth-century hand in the margin of the first leaf of a Speculum which reads Nicolaus a Lyra dicitur hanc compilacionem fecisse .[11]

As evidence of Ludolphus' authorship Lutz and Perdrizet cite several factors. Originally a Dominican monk, Ludolphus joined the Carthusian Order in 1340 and wrote the Vita christi , in which he included Chapter IX of the Speculum and other sections of the text without crediting his source. This was taken to show that he was incorporating an earlier work of his own, but it has since been shown that he borrowed twenty-three fragments of the Horologium sapientiæ by Henricus Suso, and portions of texts by other authors, without acknowledgment.[12] This was common practice in the writings of the Middle Ages and cannot, therefore, be clear evidence that Ludolphus wrote the Speculum .

There are, however, good reasons to place the origin of the text in a Dominican monastery. In Chapter III, the Immaculate Conception is described in accordance with the doctrines of the Dominican Order; Chapter XXXVII tells of the vision of St. Dominic; Chapter XXX includes the theory of the sanctification before birth expressed by St. Thomas Aquinas, a Dominican, and special honor is also paid to him in Chapter XLII.

The text in Chapter XXXIX tells of the knighting of Christ: his charger is the ass of Palm Sunday; his helmet is the crown of thorns; his gloves and his spurs are the nails of the Crucifixion; and his champion is the Virgin Mary. The ceremony is executed more Alemannico (in the German way) with sword strokes on the neck. At that period the wording would have indicated a location in southwest Germany, or Swabia. The text would seem to have been composed in a convent of the Preaching Brothers of Strassburg (at that time, within the borders of Swabia), by a Dominican of Saxon origin.[13]

Complete manuscripts of the Speculum include a Prologue of two pages, a Prohemium of four (both without illustrations), forty-two chapters with the miniatures above the four text columns (herein referred to as a, b, c, and d) followed by three chapters of double length with eight miniatures, requiring four pages each. After the two chapters devoted to the first age of the world, forty follow the typological pattern in which the first image from a New Testament event is accompanied by three prefigurations taken from the Old Testament or other sources mentioned earlier. In the last three chapters, devoted to the Seven Stations of the Passion and the Seven Sorrows and the Seven Joys of Mary, the miniatures are not typological. The complete work, then, would require fifty-one leaves.

The precise mathematical format of the Speculum is reflected in the linear scheme. The text of the first forty-two chapters has twenty-five lines to a column, two columns to a page; the bottom line of the first is rhymed with the top line of the second column. There are four columns or 100 lines to each chapter, filling a page-opening. The last three chapters are twenty-six lines to a column, eight columns to a chapter, filling two page-openings. The Prologue occupies 100 lines and the Prohemium, or table of contents of the chapters, has 300 lines.

While most manuscripts follow this pattern, some include only forty-two chapters, omitting the last three, and some omit the Prologue or the Prohemium, or both. There are captions over the miniatures in some copies but these differ from one to another. The references which appear sometimes at the foot or at the head of the text columns, naming the book of the Bible or some other source, also vary or are omitted. In the text itself, copyists have made minor changes but retained the rhymed doublets.

It must have been of great value to the scribes, the blockbook maker, and the incunabulists that the earliest known manuscripts laid out such a specific format for the Speculum , which has been followed, with some variations, through the many copies.

The oldest summa listing the Speculum is not dated, but it was made about the middle of the fourteenth century by Ulrich, Abbot of Lilienfeld. It notes only forty-two chapters. It has been suggested that the last three chapters were added later.[14] However, the copies mentioned above, made from a manuscript dated 1324, which predates the summa , include forty-five chapters. The copyist of the manuscript in the summa must, therefore, have deleted the last three chapters, or worked from an abbreviated example.

Each chapter can be thought of as an inspiration for a sermon by preaching Brothers, to whom the pictures were as important as the text. The persons and scenes had religious significance which could be disseminated to the unlearned more dramatically through images than through words. In some manuscripts the typological lesson is emphasized by parallel compositions of the four pictures within each chapter.

In the minds of the theologians of the Middle Ages the religious symbolism of every flower, plant, animal, and form was determined, and this is reflected by the artists and miniaturists of the Speculum . We find also, in some of the finest manuscripts, their obedience to the traditional rules of a kind of mathematics as well, in which position, grouping, symmetry, and number have mystic meaning. These systems were transmitted through the Church to craftsmen, sculptors, painters, and miniaturists from one end of Europe to the other.[15]

No works of the late Gothic had more influence on artists working in all the media than the Biblia pauperum and the Speculum humanæ salvationis . The influence of the typological text and illustrations of the latter can be seen in the fourteenth-century stained glass windows of churches at Mulhouse, Colmar, Rouffach, and Wissembourg. The woodcuts of the blockbooks clearly appear in designs of the fifteenth -century sculptures of the church of Saint-Maurice at Vienne and in the famous tapestries of the Life of Christ at La Chaise-Dieu and the series at Rheims.[16] Mâle states that one could be sure that any Flemish artist of importance had in his atelier manuscripts of these two works. Jan van Eyck, in 1440, worked from a Speculum in the triptych for the church of Saint-Martin in Ypres. The typological treatment of the Nativity was traditional

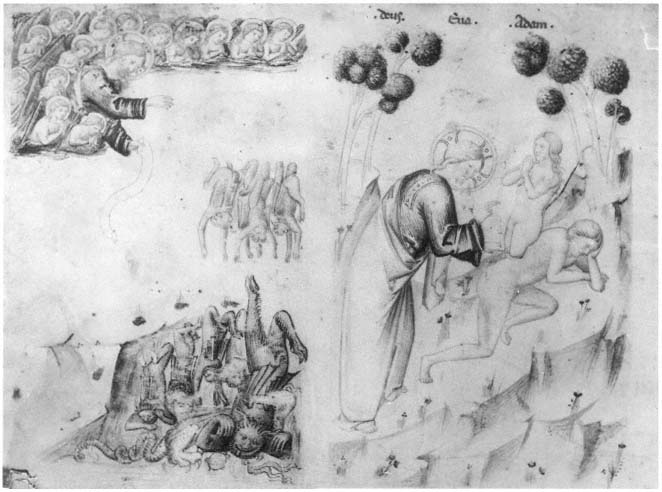

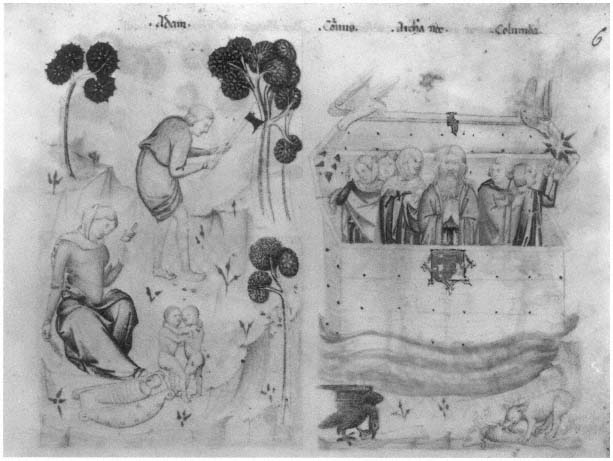

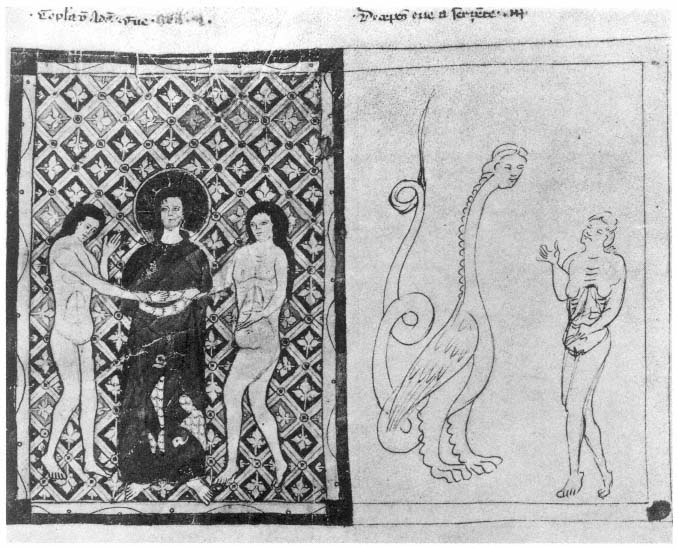

II-2.

a. The Fall of Lucifer,

b. The Creation of Eve.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter I.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. lat. 9584, fol. 4 verso.

and one might assume that Van Eyck could find it in other sources, but on the exterior of the side panel is the earliest example, in panel painting, of the Annunciation to Augustus and the Tiburtine Sibyl just as it appears in the Speculum . This subject entered the artistic iconography specifically through the Speculum text and image. There was a copy also in the atelier of Roger van der Weyden, as can be seen in the famous Bladelin triptych, where the same prefigurations of the Nativity are pictured.[17] The use of both books as sources, in a single work of art, is not uncommon.

While the artists of the Speculum created manuscript miniatures that are very different in style from one copy to the other, they are fairly consistent in the iconography and the symbolism suited to the subjects. A rewarding study could be made of the many Latin manuscripts of the Speculum which are still preserved. We have limited our work to the few which follow, in order to describe and illustrate some of the varieties of treatment. The miniatures may be compared with the woodcuts of the blockbooks by reference to our Chapter VI.

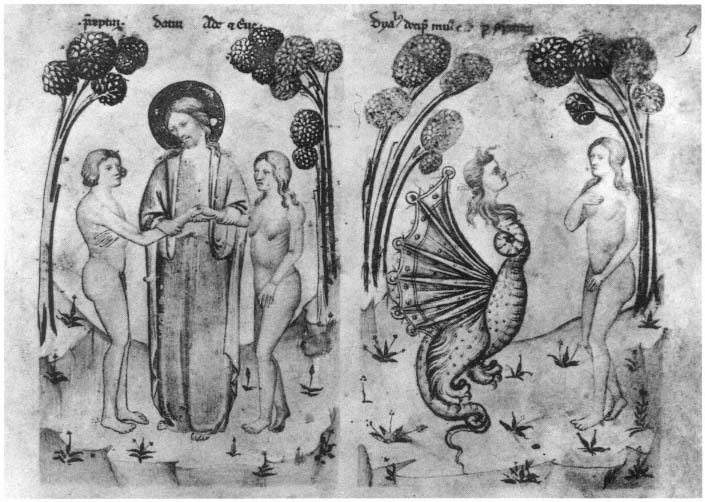

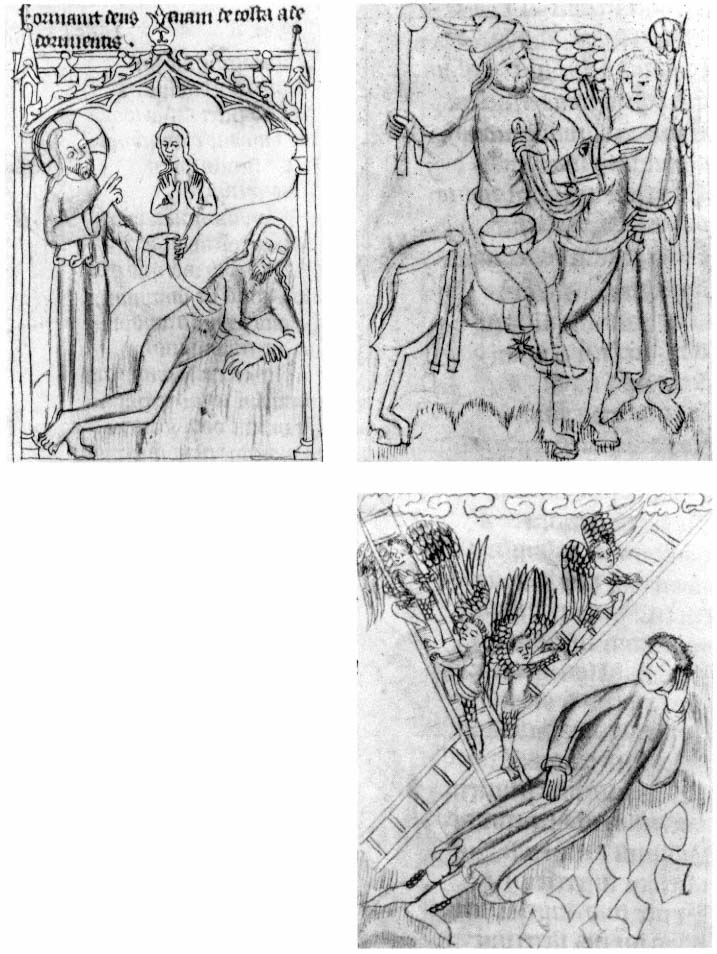

II-3.

c. The Marriage of Adam and Eve.

d. The Temptation.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter I.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. lat. 9584, fol. 5 recto.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. Lat. 9584

This copy is on parchment in small folio, 29.4 × 22 cm., and contains twenty leaves bound up in the wrong order. It was made sometime in the last quarter of the fourteenth century, from the same model as that of the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Ms. 593, a model which lacked the text and pictures from Chapter XVI c and d, to XXIV a and b. Both copies are of Italian origin and contain the interrupted text and the date of 1324 in the Prohemium, which must be the date of the model, not of the copies.

At an unknown date Ms. lat. 9584 was divided in two, and the other portion is at Oxford. In the latter the text has been cut off and only the miniatures, in line and wash, remain. The two parts were reproduced together in a facsimile in 1926, and the presence of a miniature for Chapter XLV, from the Oxford portion, shows that the inscription of the complete manuscript was intended.[18]

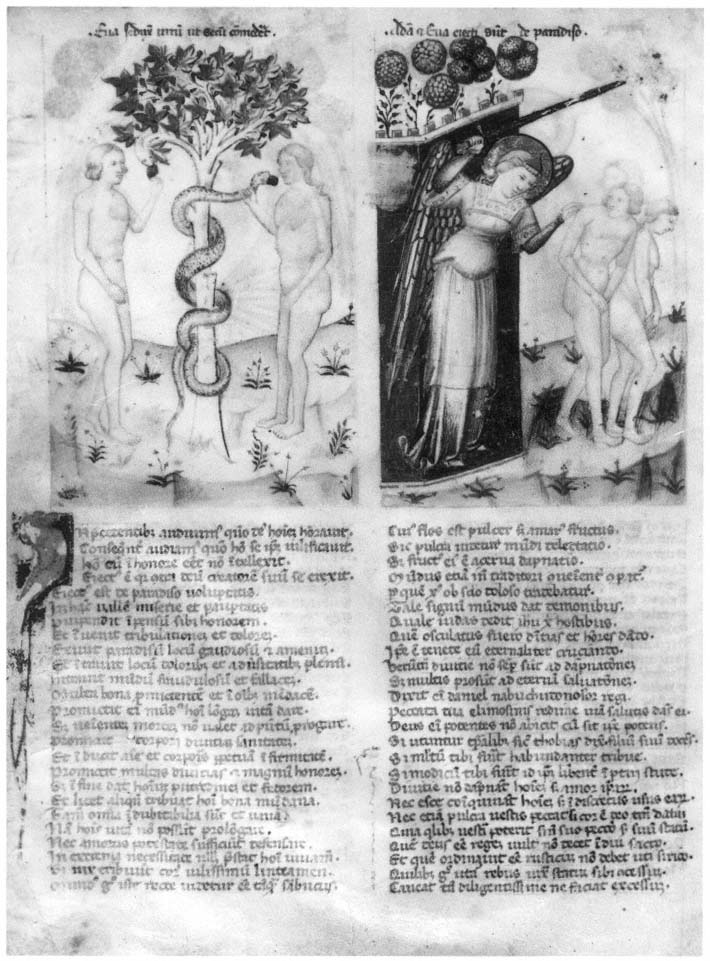

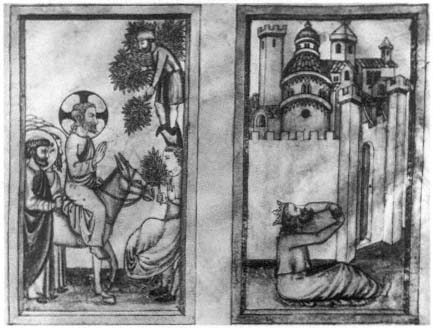

II-4.

a. The Fall.

b. The Expulsion.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter II.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. lat. 9584, fol. 5 verso.

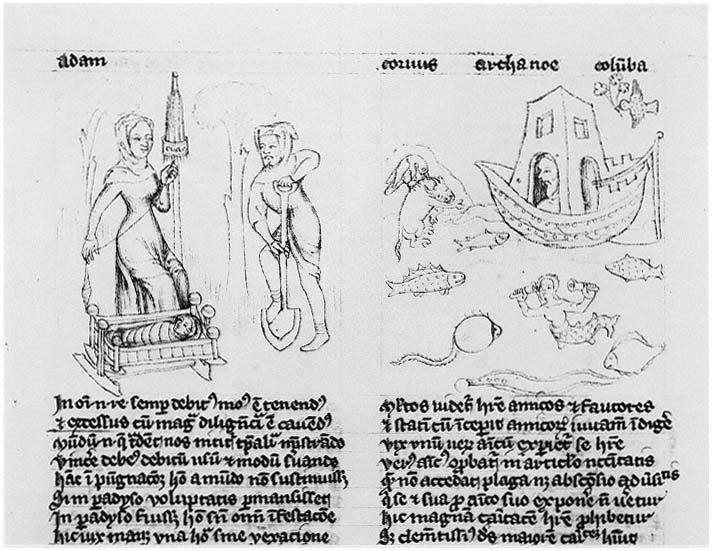

II-5.

c. Adam Tills, Eve Spins.

d. Noah's Ark.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter II.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Ms. lat. 9584, fol. 6 recto.

The script is an Italian Gothic of the middle of the fourteenth century, and according to Bernard Berenson, the miniatures in pen and wash are Florentine from the last quarter of the century (figs. II-2, 3). He finds them the work of a miniaturist who had travelled widely and included, in his images, architecture with a Byzantine influence and armor in the French style. The clothing of persons in the mode of the day does not seem to appear in Tuscan art earlier than 1370, but it can clearly be seen in this manuscript (e.g. the angel in fig. II-4).

It is curious that in the miniature of Adam digging while Eve spins, a new baby is lying in a cradle beside Cain and Abel. Presumably the artist did not know that Seth was born long after the murder of Abel by Cain (fig. II-5).

Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Ms. Lat. 593

Written in an Italian Gothic hand similar to B.N. Ms. fr. 9584 but not by the same scribe, this manuscript is on parchment in small folio size, 32.2 × 21.5 cm. It is a "sister" book to the Paris manuscript above and was produced in the same scriptorium, for the missing chapters are lacking in both, and it appears they were copied from the same model, dated 1324. The errors in

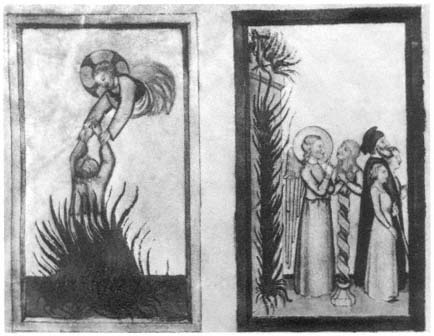

II-6.

a. The Lord Delivers Abraham from Ur of

the Chaldees and from the Fire.

b. Lot is Delivered from Sodom.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter XXXI.

Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Paris, Ms. lat. 593.

II-7.

a. Christ Wept over the City of Jerusalem.

b. Jeremiah Lamented over Jerusalem.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter XV.

Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, Paris, Ms. lat. 593.

the miniature titles are also the same in the two manuscripts. Berenson thought that the miniatures in the Arsenal copy were done by an Umbrian artist, and he contrasts the "bald landscapes" and stiff rustic figures with the elegant flowing lines of the Florentine manuscript. Judging by the architecture in the miniatures, particularly in Chapter XV b, the view of the dome in Jerusalem (fig. II-7), he proposes that the illustrations were made after 1400, but the notice in the Samaran and Marichal catalogue attributes the illumination to Taddeo Gaddi (1300–1366), a Florentine.[19]

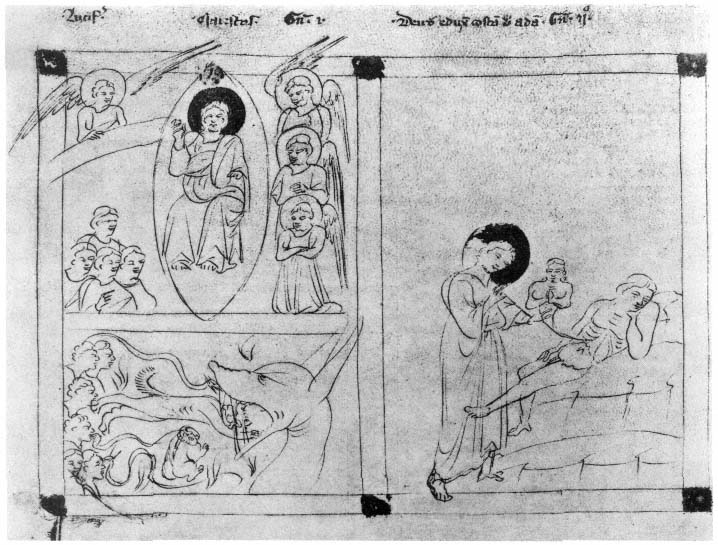

II-8.

a. The Fall of Lucifer.

b. The Creation of Eve.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter I.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Clm 146, fol. 3 verso.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 146

For their extensive study of the Speculum humanæ salvationis , Lutz and Perdrizet chose to reproduce, with commentary, the Munich copy Clm 146.[20] It is in folio, on fifty-one parchment leaves, and contains the Prohemium, the Prologue, and forty-five chapters. There are 192 pen drawings, and initials painted in red and blue (figs. II-8, 9, 10, 11). While this copy is not dated, it was presumably written about the middle of the fourteenth century and it contains a sort of colophon statement that it was done in the Johannite monastery at Selestat (near Strasbourg). It was chosen as an authoritative text because of its origin near to the Dominican Monastery where it was assumed that the Speculum was first written, and because of the obvious care of the copyist. However it has since been proposed that this manuscript was copied from one which

II-9.

c. The Marriage of Adam and Eve.

d. The Temptation.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter I.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Clm 146, fol. 4 recto.

originated in Bologna about 1330, traveled to Toledo where it was destroyed in the Spanish civil war of the nineteen-thirties, but whose existence has been revealed by pictures of certain pages made by a Barcelona photographer.[21]

The miniatures of the Munich copy are framed in pen lines and in some of them the corners and the halos are painted in a terra cotta color, possibly to prepare them for the addition of gold. The only finished painted miniature, of God with a gold halo uniting Adam and Eve (fig. II-9), indicates that it was intended that all the miniatures be colored. The devil of the Temptation, who takes many forms in the Speculum illustrations, appears here as a basilisk with an enormous looped tail.

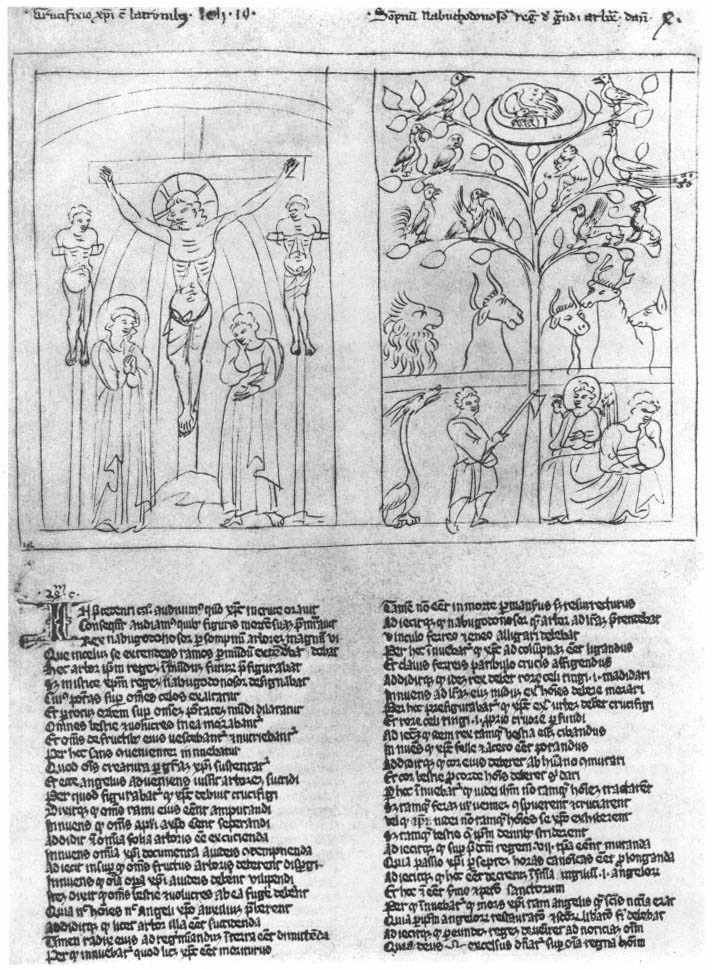

II-10.

a. Christ on the Cross.

b. Nebuchadnezzar's Dream of the Tree Cut Down.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter XXIV.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Clm 146, fol. 26 verso.

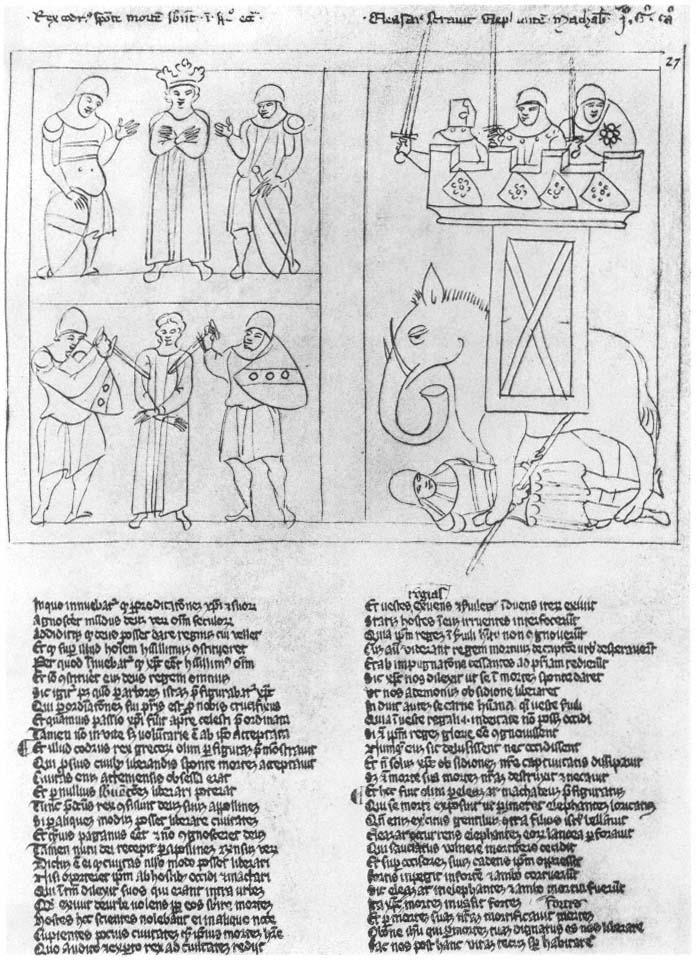

II-11.

c. King Codrus Dedicates Himself in Death.

d. Eleazar Kills the Elephant and is Crushed.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter XXIV.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Clm 146, fol. 27 recto.

II-12.

a. The Resurrection.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter XXXII.

Yale University, The Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Ms. 27, fol. 36 verso.

Yale University, the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Ms. 27

This late fourteenth-century manuscript of the Speculum humanæ salvationis is bound with the Pseudo-Bonaventura Meditationes de passione christi . It was copied in England and was given to the Collegiate School in Connecticut by Elihu Yale in 1714. (The college was re-named for the philanthropist in 1718.) It is said to be the first illuminated manuscript to come to a North American institutional library. It contains 104 leaves of vellum which measure 28 × 19 cm. The Speculum part contains the Prologue, the Prohemium, forty-five chapters and an undated Explicit. Originally there were 180 drawings of which eighteen have been removed. The miniatures are drawn with a very fine pen, in ink of the same color as the text, but paler, and they were probably not made by a professional miniaturist (figs. II-12, 13). It is in its original binding, of a type known as a "girdle book." These were made by covering the volume, already bound in sheepskin on wooden boards, with an envelope of sheepskin which culminates in a knot formed at the end of the skin, and clasps. This Speculum , weighing three pounds eight ounces, would have been quite uncomfortable hanging from a girdle and was probably designed to hang from the saddle of a traveller on horseback.[22]

II-13.

The Creation of Eve, Chapter I b, fol. 7 recto.

Balaam's Ass and the Angel, Chapter III d, fol. 9 recto.

Jacob's Ladder, Chapter XXXIII b, fol. 37 verso.

Speculum humanæ salvationis .

Yale University, The Beinecke Rare Book

and Manuscript Library, Ms. 27.

Hessische Landes- und Hochschulbibliothek Darmstadt, Hs 2505

This delightful manuscript on parchment was written ca.1360. It contains seventy-one leaves, 35 × 20 cm., and thirty-four chapters with pictures painted in vivid washes. The archives of Dortmund reveal that it belonged to L. Kleppingk from 1372 to 1388/89 and hence it is known as the Cleppinck Speculum . According to an entry at the end of the text it was in the Cloister of Clarissa in Clarenberg, Westphalia, in about 1400. The manuscript is incomplete, lacking many leaves but ending with Chapter XL, so that it was probably copied as the abbreviated version. The miniatures are placed in an unusual way, with the four illustrations for each chapter on facing pages without text (Plates II-1 and II-2). The images are in two compartments in vertical sequence and are of formal dramatic design. The typological pattern of the Speculum is followed, but with extremely unusual interpretations in the miniatures. The rhymed text is inscribed in single columns on the tall narrow pages following the openings containing the miniatures.[23]

Hessische Landes- und Hochschulbibliothek Darmstadt, Hs 720

Written in a careful Bastarda hand in two prose columns on paper, this manuscript has 200 pen and wash drawings, four for each chapter in the usual typological program, but is unusual in that the chapters begin always on a recto page and end on the verso. There are sixty-four leaves, 36.5 × 27.5 cm., made in southern Germany about 1440, but the provenance of the codex is not recorded.

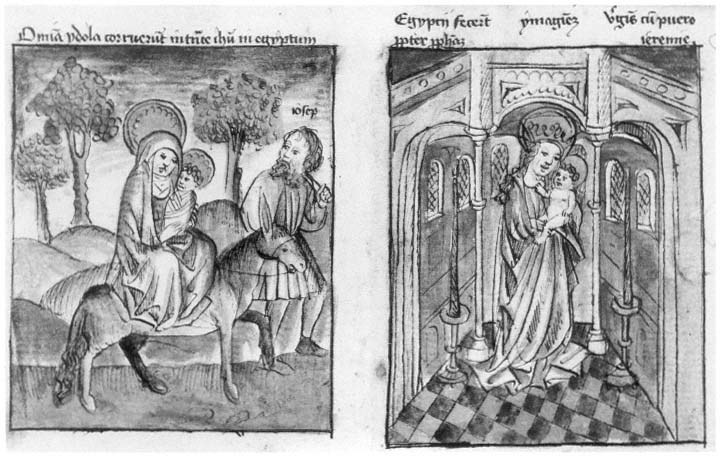

Its opening miniature on folio 1 verso is unusual for a Speculum manuscript. The page is divided vertically: the left half depicts the Tree of Virtues rising from a mandorla of Christ enthroned; the right half shows the Tree of Vices coming out of a winged monster (Plate II-4).[24] Unlike the Darmstadt Hs 2505 of the Speculum , the entry into Egypt of Chapter XI does not show the falling of the idols at the passage of Christ (fig. II-15).

II-14.

The Pain of the Damned in Hell.

How David Punished His Enemies.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter XLI.

Hessische Landes- und Hochschulbibliothek Darmstadt,

Hs 720, fol. 47 recto.

II-15.

The Flight into Egypt.

The Egyptian Statue of the Virgin and Child.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter XI.

Hessische Landes- und Hochschulbibliothek Darmstadt,

Hs 720, fol. 17 recto.

II-16.

c. Adam Tills and Eve Spins.

d. Noah's Ark.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter II.

Harvard University, The Houghton Library, Ms. Lat. 121, fol. 5 verso.

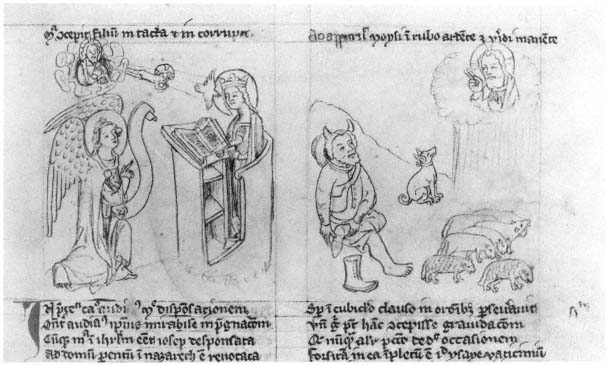

Harvard University, the Houghton Library, Ms. Lat. 121

Written in a small rounded Gothic script in the typical two-column, twenty-five-line format on forty-eight vellum leaves, 23 × 16.5 cm., this manuscript includes forty-five chapters and seventy-five pen and ink drawings in a primitive but lively style (figs. II-16, 17, 18). There are single-line titles over the pictures, but no elaborate initials or illumination. After the first eighteen chapters, blank spaces are left for the miniatures, which were never completed. Those of the early chapters appear to be of Bohemian origin or influence and were done in the late fourteenth century. The manuscript was formerly in the Monastery of San Pedro de Roda in Catalonia and came to Harvard in 1943.[25]

II-17.

a. The Annunciation of the Birth of Mary.

b. King Astyages Sees a Marvel in a Dream.

Speculum humanæ salvationis . Chapter III.

Harvard University, The Houghton Library, Ms. Lat. 121, for. 6 recto.

II-18.

a. The Annunciation to the Virgin.

b. God Appears to Moses in the Burning Bush.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter VII.

Harvard University, The Houghton Library, Ms. Lat. 121, fol. 10 recto.

II-19.

a. The Gifts of the Magi.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter IX.

The Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 385, fol. 11 verso.

II-20.

c. David Kills Goliath.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter XIII.

The Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 385, fol. 16 recto.

The Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 385

This mid-fifteenth-century Speculum manuscript on vellum, 29 × 24 cm., was written in Flanders and contains, on folio 51 verso, a long prayer in Flemish verse. There are miniatures at the head of each column of twenty-five lines, with titles above them and the source reference beneath. All forty-five chapters are included. The illustrations, in pen and wash, are very spirited and well drawn, containing banderoles identifying the persons, and other inscriptions (figs. II-19, 20, 21). There are a few decorated chapter-heading initials.

The illustration in Chapter IX-a shows three magi, bearing their gifts; one points at a very large star while another grasps his arm in confirmation and joy. The third has removed his crown and holds the lid of his offering bowl while the Christ child seems to dip in his hand. The same scene is shown in Chapter XLV-e, but in that one a flimsy manger appears with a woven fence. The child is again putting his left hand into the bowl and holds the lid (or is it a wine goblet?) in his right.

II-21.

a. The Nativity of the Virgin.

b. The Tree of Jesse.

Speculum humanæ salvationis , Chapter IV.

The Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 385, fol. 6 verso.

II-22.

c. Gideon's Fleece.

Speculum humanae salvationis , Chapter VII.

The Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 766, fol. 29 recto.

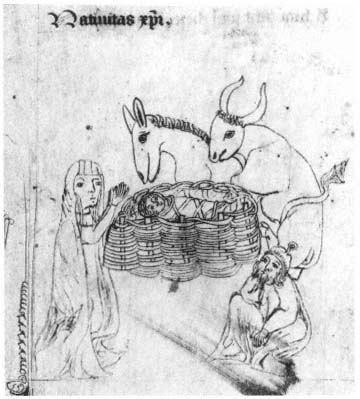

II-23.

a. The Nativity of Christ,

Chapter VIII, fol. 29 verso.

The Pierpont Morgan Library, M. 766

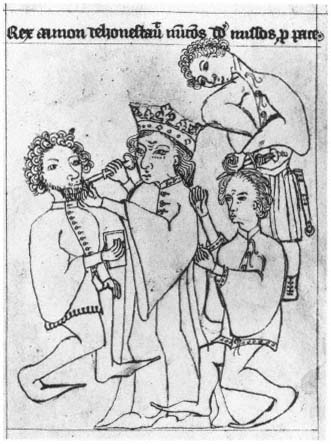

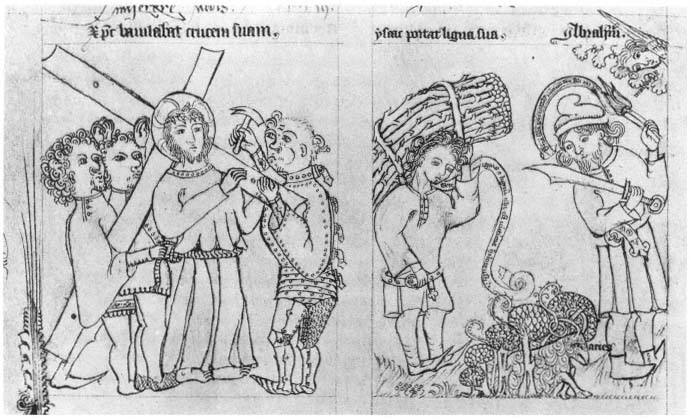

This English manuscript of the early fifteenth century has seventy-one leaves on vellum, 32.5 × 24 cm., of which two are blank. There are 192 pen drawings of very primitive character, without shading and with very little rendering of the ground or landscape. The costumes are partly imagined and partly those of the period, with elaborate attention to such details as buttons and nail-heads and the joints of armor (figs. II-22, 23, 24, 25, 26). Some of the scenes differ strongly in their iconography from other Speculum manuscripts, and as a result of the lack of perspective, the Christ child's cradle is floating in the air. There is no suggestion of a manger or shelter of any kind (fig. II-23). The drawings are in the same ink as the text which suggests that they were sketched by the scribe himself.

On folio 1 verso is written "Officium de Sancto Johanne de Bridlyntona" in a script very like that of the text. This Johannes was a regular prior of Bridlington in the County of York; he had studied at Oxford and was canonized in 1401. He was worshipped as a saint in Bridlington and its environs within a few years after his death in 1379.[26]

II-24.

b. Daniel Destroys Bel and Kills the Lion,

Chapter XIII, fol. 34 verso.

II-25.

d. King Ammon Deals Dishonestly with David's Messengers.

Chapter XXI, fol. 43 recto.

II-26.

a. Christ Bearing his Cross.

Chapter XXII, fol. 43 verso.

b. Isaac Carrying the Wood for his Immolation.

Chapter XXII, fol. 43 verso.