I—

Medieval Book Production in the Low Countries

The period in which the Speculum humanæ salvationis was composed, the first quarter of the fourteenth century, was dominated by medieval religious concepts that affected every aspect of daily life from birth to death. They were reflected in art, architecture, sculpture, music, and drama, and the making of books was largely confined, from the fall of the Roman Empire, to monasteries, convents and ecclesiastical organizations for several hundred years. Religious orders had been established and spread increasingly all over the western world. Pilgrims and monks carried their manuscripts from one monastery to another across great distances, and because they had, in Latin, a common language, the production and exchange of texts by and for these centers flourished. Life in monastic communities provided the seclusion, the freedom from worldly concerns and distractions, and the focal disciplines that were ideally suited to the copying and to the decoration of books.

From Carolingian times on, scriptoria with illuminators also existed in the courts of royalty and nobility and produced countless beautiful codices with miniatures, not all of a religious nature, but including chivalric and historical texts. By the second half of the twelfth century the art of miniaturists and illuminators was so keenly appreciated that even fairly recent writing, such as the Historia scholastica of Petrus Comestor (d.1178), a combination of sacred and profane history, was luxuriously executed.[1]

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, under noble and royal patronage, the French manuscripts were unrivalled, but the ateliers, which had nurtured miniaturists from Flanders, Holland, Bohemia, and Italy, declined after 1430 as a result of the impoverishment of the nobility by the Hundred Years' War. In the Low Countries, although the French influence was strong, miniature painting and illumination developed a brilliant independent vigor with

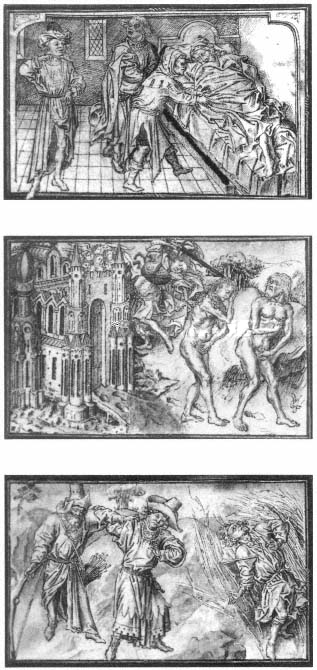

I-2.

The Shame of Noah, fol. 15 verso.

The Expulsion from Eden, fol. 9 verso.

The Vengeance of Lamech, fol. 11 verso.

Dutch Bible, 1439.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, Cod. Germ. 1102.

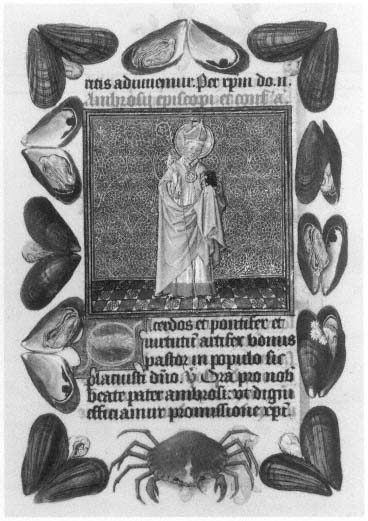

I-3.

Bishop Ambrosius with Mussels and Crab.

The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, c.1440.

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, M. 917, p. 244.

the support of the wealthy burghers, and particularly the powerful Dukes of Burgundy. Their vast domains, acquired by conquest, treaty, purchase, and marriage, included most of the present Netherlands and Belgium, the then extensive duchy of Luxembourg, and Picardy, Artois, Alsace, Lorraine, the Franche-Comté, Nivernais, and Charolais.

As an Episcopal See, Utrecht, in the North, became a center for the illustration of books between 1430 and 1450. The debt of its artists to the Ghent-Bruges school of the Van Eycks, in terms of both style and composition, can be seen in the work of many of the Utrecht miniaturists. In this period, a different and vigorous Dutch style appeared, notably in the work of the Master of Catherine of Cleves, whose magnificent Book of Hours (c.1440), divided into two parts, is now in The Pierpont Morgan Library, Mss. 917 and 945. This artist is also credited with some of the miniatures in the fine Dutch Bible now in the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich, dated 1439 (fig. 1-2).[2]

By the middle of the century, however, some of the best of the Dutch miniaturists, such as Willem Vrelant, emigrated to Bruges when that town restricted in 1403, 1426, and 1457 the importation of detached miniatures made in Utrecht.[3] The passage of such strict measures indicated the importance of the sale of Dutch miniatures and the unusual practice of bookmaking in Utrecht. There, the scribes wrote the text continuously, leaving space for initials, but not for illustrations. These were painted on separate leaves and inserted into the text or, evidently in many cases, sent to Bruges, where the presence of the Burgundian court had established that city as a center of de luxe manuscript production. Vrelant and other Dutch artists appear in the official records as working for the court after the Bruges edict.[4]

Another and very different source of the Netherlandish books was the religious movement known as the Devotio moderna which originated in the teaching, sermons, and writings of Geert Grote at the end of the fourteenth century. His reformist concepts became the spiritual basis for the many religious communities called the Brethren of the Common Life. The first commune was actually that of Sisters, a group of pious women who dedicated themselves, without taking vows, to the conventual life in the service of God, in the house in Deventer given to them by Geert Grote. The movement spread, and communities of Brothers as well as Sisters were established with centers throughout the Low Countries and in Germany and northern Switzerland. It attracted intellectuals and deeply pious people by a commitment to sincerity, to simplicity, and to work.

Among the followers of the Devotio moderna , but in a more traditional monastic organization, were the Augustinian Regular Canons of the congregation of Windesheim. These retained a

close relationship with the communities of the Brothers and the Sisters of the Common Life.[5] All were devoted to the establishment of schools and the teaching of religion to the common people. Producing manuscripts was at the core of their activities, including many in the vernacular tongue, and some with miniatures and illumination such as the fine five-volume Latin Bible inscribed by Thomas a Kempis in the Agnietenberg community, which is now in the Hessische Landes- und Hochschulbibliothek Darmstadt.

The rules for the regulation of daily work were posted in the communities and have been preserved.[6] They included scheduled hours daily in the copying, illustrating, and binding of manuscripts, both for their own use and as commissioned works to supplement the income of the community.

In scriptoria of monasteries in the Catholic orders, the texts were often richly illuminated and included Bibles, the lives and miracles of those saints to whom they had a special devotion, and the indispensable writings of the Fathers of the Church. Small portable Latin Bibles were produced in quantity, written in exquisite regular Gothic hands on the finest parchment, often containing miniatures and pictorial or historiated initials.[7]

In the actual work of making books, the medieval scribe must have begun, as would a modern designer, by determining the amount of text which would make a page when written in the chosen script and size and in the desired format. To this must have been added the space planned for miniatures, initials, headings, captions, and sometimes areas for glosses. This calculation would reveal the number of sheets of parchment or vellum needed. Sometimes the skins were prepared by the scribes themselves as evening work when the light was too poor for writing,[8] but probably it was more common to obtain them from the parchment maker. Once the scribe acquired them his next step would be to stack the sheets, possibly in threes, fours, or fives, for gatherings that would make, when the sheets were folded, from twelve to twenty pages. From his basic format plan, he would prick, through the parchment stack, the positions of the margins and the grid for the guide lines of the script. The points would then be connected by ruling lines in pale colored ink or by blind scoring.

Whether the scribe actually wrote in a sewn gathering, or even a bound book, as is so often shown in miniatures (fig. I-1), is difficult to determine. The practice may sometimes have been to inscribe a single four-page sheet of the text consecutively, turning over or replacing the pages to preserve the sequence.[9] There are examples of manuscripts in which a full skin was folded

twice to make eight pages, or three times to make sixteen, where the scribe wrote his text leaving the sheet uncut.[10] Scribes are also shown seated at steeply slanted, double-faced desks with the skin folded over the top in the direction of the animal's spine, but it must have been awkward to turn it around or upside-down for each new page. Probably this was the exception, and one may assume that the sheets were usually cut into bi-folios before inscription.

In the workshops of the Brethren of the Common Life, binding was clearly part of the activity, and a number of bindings from these workshops in different locations have been identified. Fifteenth-century metal book fittings were excavated in 1905–06 on the site of the Brussels house. All the known bindings of the Brothers are panel-stamped, many with a small name, "nazaret," stamped by hand, which identified the Brussels community.[11] Panel-stamped bindings were common in the fifteenth century, particularly in the Low Countries, and originated as early as 1250 in Flanders. The dies and panels were engraved in metal, like coins or medallions, and stamped into the leather, not by hand but by a screw press. The patterns and designs were copied from engraved playing cards, or models possibly disseminated in pattern books.[12] Binding work was done not only for the house itself but also for the same customers to whom devotional books were supplied, and for other convents.

The evidence of the blockbooks in which condensed text is carved on the same block as a religious picture also points to their production, in multiple copies, in the centers of the Brethren of the Common Life. The Exercitium super pater noster and the Spirituale pomerium could be attributed to the communities of Sept-Fontaines and Groenendael. These, and the other Netherlandish blockbooks, are discussed in our Chapter IV. The dates of their origins and their localizations are still controversial, but the communities of the Sisters and of the Brothers of the Common Life, with their dedication to educate and their exceptional tradition of producing and distributing books in the Low Countries in the fifteenth century, might well have been the centers for the creation and dissemination of this new means of popular communication.

Profound changes which affected the making of books had been taking place in the social, intellectual, and religious spheres since the end of the twelfth century. The instruction of laymen and the foundation of universities were taking place concurrently with the development of a wealthy and independent middle class. The conditions under which books were written, copied, distributed, and read were being secularized, and the centers of intellectual life began to shift away from the monasteries and toward a new constituency of readers. Most of these were clerics who retained a bond with the ecclesiastical establishments, but they and their professors had need of many texts, reference works, and commentaries. The universities also had to

develop organized libraries. The pecia system of copying separate signatures was instituted in France, Italy, and Spain, but it was never adopted in the Low Countries.[13]

During the late fourteenth century, while the religious houses continued to produce manuscripts, lay scriptoria appeared around the universities and in the market places of the cities. Professional scribes were available to execute contracts, letters, accounts, and documents on commission. Probably few of these were capable of fine book work, but there may have been some that produced illuminated manuscripts. Books could be copied, of course, by anyone who could write, and the number of "occasional" scribes who made books for themselves as well as for others may well have been as great as the professional scriveners.[14]

The introduction of paper had important results in the making and the price of books. Paper did not, of course, replace parchment and vellum rapidly, and the difference in price at the outset was not great, but it promoted the specialization of vellum and parchment for use in official documents and de luxe books. The early papers were comparatively heavy and the surfaces did not lend themselves so happily to the pen or brush. While small handwritten Latin Bibles on fine parchment were readily portable, the early printed Bibles on paper required two large volumes. But gradually the use of paper permitted the introduction of ordinary school books to the market in a much greater quantity and at less expense than the vellum and parchment ones.

In Flanders, and particularly at Bruges, paper was in use from the first years of the fourteenth century. The pampiermakers are found in the accounts of the city from 1304.[15] These must have been merchants of imported papers and not papermakers themselves, for the first paper mill in Flanders was not established until 1405, probably due to the lack of rapidly flowing water.[16] The paper used in the Low Countries came from mills on rivers in what is now central and northeastern France: the Moselle, the Meuse, the Marne, and the Saulx. The rivers provided water power, the medium for pulping, and the downstream transportation to the shipping arteries of the Rhine and the Seine. The most important papermaking towns were Metz, Bar-le-Duc, Troyes, and Epinal, and their products were distributed primarily through Antwerp and Bruges.[17]

To return to the blockbooks, it seems that the number of lay woodcutters working at illustration in the middle of the fifteenth century was very small. According to an art historian of

Netherlandish woodcutting, not more than twenty-five were active in book illustration in the last quarter of the century,[18] and there must have been even fewer before 1475. Outside of the religious communities, the long-established guilds for painters, illuminators, and carpenters were strictly organized. In 1452 a trial took place in Louvain in which the guild of carpenters sued Jan van den Berghe, whose work was the cutting of letters and pictures (letteren ende beeldeprynten ), maintaining that he must join the guild and conform to the prescribed obligations.[19] The engraver argued that his work was a unique art unlike any other in the city, and that it was concerned with the clergy. He seems to have been the only one to exercise his craft in Louvain at that time outside the monasteries.[20] Arthur M. Hind in An Introduction to a History of Woodcut writes," it can therefore be inferred with certainty that he was engaged in the cutting of some book of a religious kind like the Netherlandish blockbooks."[21] In turn, the guild replied that its members were also cutters of letters and images, that this occupation required the same tools as the carpenters, barrel makers, etc., and that their guild would not allow Van den Berghe to invoke the liberty of clerics. The magistrate of Louvain granted the case of the guild but exempted Van den Berghe from the enrollment fees.[22]

However, as we have seen, there were certainly engravers of letters and images in the religious communities and attached to the courts of the nobility, over which the guilds had no control, and where woodcutting flourished. These craftsmen were still practicing long after the first printing presses were established in the Low Countries. They supplied woodcuts for early printed books at Louvain, Brussels, Utrecht, and Haarlem.