AIDS Goes Heterosexual

Scientists commonly point out that AIDS arrived at the "right time"—that is, a time when basic science research in virology and immunology could provide a foundation for an intensive research effort on AIDS. They point out that no other epidemic disease has been analyzed so quickly nor its cause so efficiently determined."[104] Despite quarrels with this view (Randy Shilts, for example, calculates that the entire workforce assigned to AIDS was a tiny fraction of the one deployed to deal with the 1982 Tylenol scare in Illinois[105] ), let us concede that a number of biomedical researchers, epidemiologists, and clinicians have greatly contributed to our understanding of AIDS and that they were able to do so in part because of scientific progress in specific fields over the last twenty years. As Simon Watney points out, however, investigations of the last two decades provide a crucial foundation for the analysis of AIDS in the human sciences as well. Such a foundation prepares us to analyze AIDS in relation to questions of language, representation, the mobilization of cultural narratives, ideology, social and intellectual differences and hierarchies, binary divisions, interpretation, and contests for meaning.[106]

Models for such analyses in relation to AIDS have primarily been carried out by members of the gay community, whose interventions have helped shape the discourse on AIDS. As gay activists contested the terminology, meanings, and interpretations produced by scientific inquiry, loaded phrases like "promiscuous" soon gave way to more neutral behavioral descriptions like "sexually active with multiple partners" (many examples of such shifts are demonstrated in the collections of AIDS papers from Science and the Journal of the American Medical Association ). It is interesting that by 1986, when women were more central to the AIDS story, scientists and physicians were speaking of "sexually active" males and "promiscuous females."[107] Other linguistic

practices relevant to the construction of gender and sexuality in AIDS discourse are enumerated by J. Z. Grover.[108] Although such linguistic activism is dismissed by Shilts as misguided public relations efforts on the part of the gay community, it is more accurately seen, as Watney and others have argued, as part of a broad and crucially important resistance to the semantic imperialism of experts and professionals.[109] Challenging the authority of science and medicine—whose meanings are part of powerful and deeply entrenched social and historical codes—remains a significant and courageous action. It also provides an important model for women as evidence accumulates that neither gender nor sexual preference provides magical protection from the virus.

In 1985 and again in 1986 the CDC reviewed the patients who "could not be classified by recognized risk factors for AIDS." Eve K. Nichols, analyzing the CDC review of "unexplained cases" and related research, concludes that "these facts suggest a possible association between a small number of AIDS cases and heterosexual promiscuity in this country."[110] Despite the hedging and the use of the loaded term promiscuity , the conclusion represents a new biomedical construction of AIDS within the official scientific establishment. In December 1986 the CDC officially reclassified 571 cases formerly classified as "none of the above."[111]

What are biomedical scientists now saying about women? In April 1987 another article on women and AIDS appeared, this in the Journal of the American Medical Association .[112] Coauthors Mary Guinan, M.D., and Ann Hardy, Ph.D., M.P.H., review the 1,819 cases of AIDS in women officially reported in the United States between 1981 and 1986. Within the risk group of heterosexual contacts of persons at risk, the percentage of women increased from 12 percent to 26 percent between 1982 and 1986 (heterosexual contact is the only transmission category in which women at present outnumber men). More than 70 percent of women with AIDS are black or Hispanic; more than 80 percent are of childbearing age. As to the "portal of entry" for the virus, it is unclear what is going on and will probably continue to be unclear until we know the precise mechanism(s) of transmission. The distinction between anal versus vaginal "portals," according to Guinan and Hardy, is relevant only if HIV cannot pass through mucous membranes and thus requires broken skin or membranes. But this is still unknown, and "if the virus can pass through intact mucous membranes, the risk of transmission through the vagina or rectum may not be different."[113]

Though its cautionary and provisional stance is welcome, this article is problematic in several ways: First, the women in risk groups are given their "status" only by virtue of their sexual partners—the men they're connected to—not by virtue of their own sexual activities. This kind of assignment appears to constitute a return to an earlier system of sociological categorization, one perhaps not fully theorized in the current situation. Second, the source of infection is determined according to a hierarchy of factors, with sexual contact taking precedence over intravenous drug use and with no dual assignments occurring; in CDC studies, therefore, infection in prostitutes has typically been assigned to contact with multiple sex partners, even though other studies, as well as prostitutes themselves, assign the source of infection to intravenous drug use.[114] And finally, above all, the purpose of studying women, we are told, is twofold: first, to use incidence in women as a general index to heterosexual spread of the virus, and second, to identify women at risk and prevent "primary" infection in them in order to prevent the majority of cases of AIDS in children that would result from these maternal risk groups without intervention.[115] There is thus no intrinsic concern for women as women . Yet, because pregnancy suppresses the immune system, any woman who gets pregnant increases her risk of infection with HIV or, if already infected, possibly increases her risk of developing active AIDS.

It is true that we need to be concerned about "future generations." During the Venetian plague of 1630-1631, ten thousand pregnant women were killed in a period of months, decimating the city's childbearing population.[116] As Shaw and Paleo point out, because the widespread practice of safer sex would drastically reduce the birth rate, childbearing might come under intense scrutiny by the state, and women of childbearing age might be among the first groups to undergo mandatory testing.[117] But surely we are also concerned about women themselves and need to give thought, in policies and practice, to them rather than simply treating them as transparent carriers who house either the future of humanity or small Damiens who will assist in furthering viral replication.

In other biomedical discourse, as I have noted, some scientists and physicians (including William Haseltine, Mathilde Krim, Jean L. Marx, and Constance Wofsy) have for some time noted that HIV may be heterosexually transmitted to and from women; and suggest that despite the small number of cases, woman-to-woman transmission may

also be possible.[118] Because of the still-unanswered questions, these professionals emphasize caution until more is known. What about lesbians, who still figure only fitfully in the biomedical story? Lesbians appear in the abstract to be at relatively low risk for HIV infection—lesbians as a group have a very low incidence of sexually transmitted disease, although the medical literature does include isolated reports, often in letters to the editor, of HIV transmission by way of female-to-female sexual contact.[119] Despite these virtually nonexistent statistics, lesbians were lumped by the public with gay men and considered just as dangerous; although lesbians in many cities are now organizing blood drives, for example, earlier attempts to do so had been defeated by the public perception that lesbians were as likely to be infected as gay men because "AIDS is a gay disease."[120] Ironically, despite many lesbians' long-standing support for and solidarity with gay men on the AIDS question, and despite the time lesbians contribute to AIDS hotlines and task forces, very little "safer sex" literature, whether directed toward homosexuals or heterosexuals is designed specifically for women whose sexual contacts are with other women.

Concerns about women in the general press have also come relatively late in the AIDS crisis. An important exception is Cindy Patton's 1985 Sex and Germs , a social and political analysis of AIDS that addresses the growing connections among contamination phobia, erotophobia, and homophobia, and proposes an agenda for progressive action.[121] Also useful is the work of Ann Guidici Fettner, Katie Leishman, Marcia Pally, Nancy Stoller Shaw, and J. Z. Grover.[122] Important and informed questions about the politics of AIDS and the "risk group" mode of describing vulnerability to HIV have consistently been asked by, among others, Randy Shilts, Peg Byron, Wayne Barrett, Simon Watney, C. Carr, Larry Kramer, and Nancy Krieger.[123] These writers have been notable. Politically oriented prostitutes' organizations have also been vocal in addressing issues of AIDS as they relate to women—advocating not only individual prevention strategies but also government responsibility for assuring safe conditions in a service industry.[124] Though the subject of women and AIDS was regularly covered only by a few women writers—primarily in radical journals in New York, San Francisco, and London—by 1986 most women's magazines had run at least one "What Women Should Do" or "What Women Need to Know" article (e.g., Vogue , New Woman ), and by 1987 mainstream feminist journals and magazines including Ms . in the United States and Spare Rib in Great Britain were providing fairly regular coverage.[125] Still, as Marea Murray

had argued in a 1985 letter to Sojourner , some women, including lesbians, continued to perceive AIDS as a problem "the boys" had brought on themselves,[126] while heterosexual women were still tending to see AIDS as nothing to do with them or as something that "self-help" procedures would guard them against. Of course, in the absence of challenge or resistance, female roles in the AIDS story remained the traditional ones: loving mother, loyal spouse, wronged lover, philanthropic celebrity; one man with AIDS even attributed his apparent remission to "the Blessed Virgin" (figs. 4 and 5).[127] But even here a confusion was evident as to who was guilty, who innocent, who was an active agent of disease, who a victim.[128]

Why was there such resistance to acknowledging women's potential to acquire and transmit AIDS and to deal clinically with AIDS as a woman's illness? One reason is certainly denial: the sheer unthinkability of AIDS unleashed upon the entire world population because, then, as someone put it at the Paris International AIDS Conference in July 1986, "the sky's the limit." Semantic imperialism breaks down in the face of the virus's ability to replicate infinitely. Instead, there is hope that the virus will be able to be "contained" within the populations already infected—i.e., "saturating" the established high-risk groups but not spreading beyond them. Though millions would die, this is still a containable subtotal of the "general population."[129]

A second reason for resistance to the role women play in the transmission of AIDS involves the potential difficulty of feminizing AIDS at this stage, after so long an identification with gay men. Shilts notes resistance to initial reports of infants and children with AIDS because the name GRID "by definition" signified a "gay disease." Yet Shilts himself, whose own account of AIDS begins with the mysterious illness in central Africa of a Danish lesbian physician, nevertheless focuses more intensely on a sexually appetitive Canadian airline attendant, a gay man who came to be identified by the CDC as "Patient Zero." Of course, as soon as the advance publicity on Shilts's book went out, the New York Post 's headline blared: "THE MAN WHO GAVE US AIDS!"[130] Others have pointed out that there is no need for female representation in the AIDS saga because gay men are already substituting for them as the Contaminated Other. Conservative journals like Commentary preserve this place by putting forth clearly and repeatedly the thesis so boldly stated by Langone: "AIDS remains the price one pays for anal intercourse."[131] In addition, Simon Watney and Larry Kramer, among others, observe that the gay community provides most of the volunteer workforce on AIDS

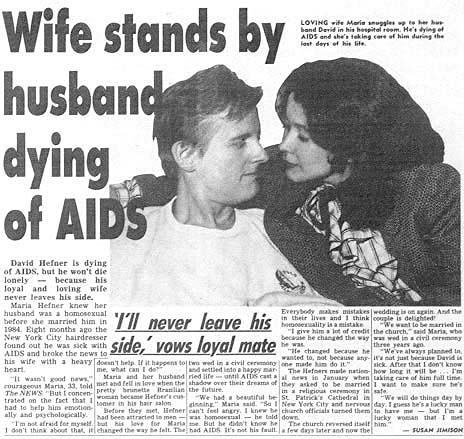

4. Although cases of women with AIDS were reported early on, women rarely appeared in the

official AIDS story except in secondary and traditional roles as mates and caretakers. Maria

Hefner was prototypical: She knew her husband was homosexual, but love conquered all. They

made national news in January 1987 after they learned he had AIDS and sought to be married

in a religious ceremony in St. Patrick's Cathedral. Weekly World News (17 February 1987, p. 17)

shows "loving wife Maria" taking care of David "during the last days of his life."

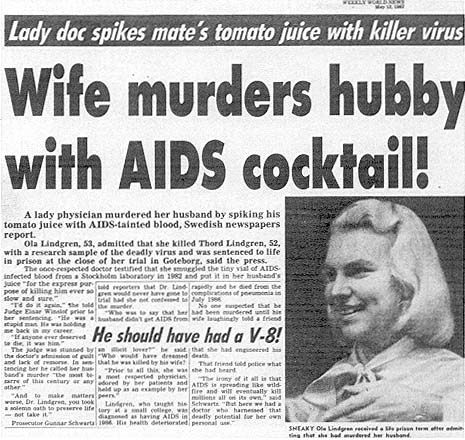

5. A few months later, another wife in Weekly World News (12 May 1987) plays quite a different

part in the AIDS story. Ola Lindgren, a Swedish physician, is reported to have murdered her

husband with virus-laden tomato juice (there is little documentation that oral transmission of

HIV would accomplish this). A photo shows "sneaky" Lindgren smiling, while the story tells

us that this "lady doc" murdered "hubby with AIDS cocktail!" Here was evidence of a female

literally carrying the virus home and giving it to her innocent husband, who gets the tabloid

fate he deserves for having married an ambitious professional woman: an epitaph from

Madison Avenue.

hotlines and other AIDS projects; when public information or television films or advertisements suggest the spread of AIDS to new groups, the "worried well" jam the phone lines beyond the capability of volunteers to answer. There are thus pragmatic reasons, until new groups of volunteers can be enlisted and trained, not to exaggerate the risk to this larger group.[132]

A third reason, I believe, essentially involves a desperate and terrorized effort to control signification. Faced with the nexus of sex and death, its fragmentation into hundreds of allied discourses, the breakdown of coherent categories of sexual identity into postmodernist "bundles of practices," and finally the virus itself with its capacities for infinite replication, who would not resist the entry of Woman, carrying the heavy baggage with which history has equipped her. As historian Allan M. Brandt notes, venereal diseases have typically been assigned a female identity; he cites a number of posters designed for U.S. servicemen, which show the equation of women with venereal disease (in one widely disseminated poster from World War II, for example, a painted prostitute walks down the street, arm in arm between Hitler and Hirohito; the caption reads: "VD: THE WORST OF THESE").[133] In this book and elsewhere, Brandt argues that AIDS has followed the historical pattern of earlier sexually transmitted diseases in generating fears of casual contact, concerns about contagion, stigmatization of victims as agents of the disease, and a search for a "magic bullet." AIDS is not yet, however, a particularly feminized disease, perhaps because, thus far, gay men have served so well as the Contaminated Other. As I have observed elsewhere, HIV is often anthropomorphized as a secret agent, but so far the gender is that of James Bond, not Mata Hari.[134] So long as the virus is characterized as "pure information," belonging to the largely male domain of perfect codes and high theory, it may resist a feminine conceptualization.

We should be aware, however, that language is already traveling from the site of the "sexually active" gay male body to the "promiscuous" female body. Numerous metaphors appearing in newspapers and scientific journals are cited by communication researchers.[135] Water metaphors appearing in 1987 ("IV drug users are the hole in the dike to the general population," "prostitutes are reservoirs of disease," and the "moist, vulnerable mucous membranes" of the female sexual organs) are reminiscent of the gendered tropes of history identified by, for example, Emily Martin and Allan M. Brandt.[136] In the Weekly World News , crème de la crème of supermarket tabloids, a loyal wife who stands by her husband with AIDS contrasts sharply with a new role for

women: a wife—a physician—who adds an HIV-infected blood sample to her husband's tomato juice and, with apparent relish, watches him develop AIDS and die.[137] The film Fatal Attraction , recapitulating Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds , gives us a taste of the consequences of "promiscuity."[138] Meanwhile, biomedical journals record the saga of an "exotic virus" infecting "exotic" African female bodies; now we learn that like this "fragile" AIDS virus our female bodies are "fragile," too, not rugged and tough after all but penetrable, "moist and vulnerable," or riddled with cracks and potholes. Are we now to become the carriers of this epidemic, ruthlessly moving everywhere? Is the female body, in fact, meaning itself, contaminating everything with its reservoirs of possibility and death? Reservoirs breaking down and letting language flow out, uncontainable within definitions? Like the virus, wearing an innocent disguise, are we not double agents, in league with the enemy? The question is how to disrupt and renegotiate the powerful cultural narratives surrounding AIDS. Homophobia, racism, and sexism are inscribed within other discourses at a high level, and it is there that they must be disrupted and challenged.

This leads to a fourth reason for the ambiguous positioning of women in AIDS discourse: Our relative failure—as feminists and as women—to address the problem of AIDS in challenging, theoretically comprehensive, or politically meaningful ways. In a final section, I will suggest some problematic aspects of current AIDS discourse by and about women as well as some useful directions toward a more satisfactory feminist analysis.