Images of Plague: Infectious Disease in the Visual Arts

Daniel M. Fox and Diane R. Karp

The word plague is of ancient origin. For thousands of years people have used it to describe events that provoked fear and suffering. The modern concept of infectious disease has, however, profoundly changed the way people think about plagues, both in the past and in our own time.

Artists have represented the impact of plagues throughout recorded history. They have necessarily employed the conventions of their time and their medium: the ways they and their audiences agreed to see and represent people and objects. The images on the following pages exemplify some of the ways artists have depicted the experience of plague during the past four centuries. We selected those images from an exhibition we assembled in 1987, "In Time of Plague: Five Centuries of Infectious Disease in the Visual Arts." This exhibition was mounted at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City between January and March of 1988 with support from the Rockefeller Foundation and the museum. The Smithsonian Institution Travelling Exhibition Service is sponsoring a two-year national tour for it, beginning in 1989.

The exhibition included about 120 objects on paper—prints, posters, and photographs—selected to tell two stories. One story is about changing conventions among artists for depicting the effects of physical afflictions that have causes not visible to the unaided eye. The other is about the impact on artists of the gradual emergence of the concept of infectious disease. During the past several centuries, most people in Western nations have come to believe that most illnesses with a sudden onset and a rapid course have distinctive natural histories that, if under-

stood, could lead to their containment, prevention, and even cure. Our two stories embrace the history both of art and of medicine. We have each addressed elsewhere some of the complexities we can only suggest here.[1] The purpose of this group of prints and photographs is to introduce readers to some of the imagery that has been created where art and illness intersect.

The concept of conventions is central to viewing these or any other visual representations. Conventions are the rules by which artists array their subjects, configure space, and use light. Artists of any age choose from the available conventions when they depict the course and consequence of illness, or any other subject. Pictures usually ratify the way contemporaries see. But artists can also use conventions to direct their audiences to new ways of seeing, for example, to new theories of the causes of infectious disease and ways of preventing or treating them.

The artists who made each of the works we present used pictorial languages of conventions that made sense to their contemporaries. Such languages must often be translated for people of other places and times. The final image in our series (fig. 15), for example, will be familiar to most late twentieth-century viewers. Many readers of this book may already have seen Alon Reininger's prize-winning photograph, taken in 1986, of Ken Meeks, a person with AIDS, being cared for by a friend. We recognize the conventions of photojournalism. This is a close-up photograph that encourages us to make up stories about particular human beings and their relationships with other people. Ken Meeks is in the foreground, looking intently at the camera. The composition directs viewers to the lesions of Kaposi's sarcoma on Meeks's arm. Many viewers would note the similarity between the pattern of the lesions and of the dots on his shirt. At the right, in the rear of the room, his friend sits in subdued light, apparently looking at Meeks and the photographer. We have all seen similar photographs of a thousand different subjects. The familiar conventions help us to interpret this one, as the photographer intended, as being about intimacy and caring for a person who is desperately ill.

Another image in the group is also about intimacy and caring (fig. 2), but it was made at a time and place that are so distant that the picture requires more explanation. This engraving by Galle depicts treatment in the sixteenth century for what we now call syphilis. The image would have been as accessible to contemporaries as Reininger's photograph is to us. They would quickly have distinguished the patient's physicians and their helpers from his domestic servants by their dress and activi-

ties. The caption would have been as redundant to them as Reininger's is to us. They would have known that the engraving depicted the preparation of a dose of hyacum, a medicine made from a log imported from the Americas and used to treat venereal disease until the twentieth century. Moreover, they would not have needed prompting to interpret the picture on the wall of the patient's room as suggesting the sexual transmission of his disease. Unlike the twentieth-century photograph, this scene is presented in conventions that emphasize both physical and emotional distance. The point of view of Reininger's camera conveys to the viewer a sense of physical proximity and emotional immediacy. His image is about a particular person and his care. Galle's sixteenth-century engraving, in contrast, generalizes about care.

We encourage readers to make similar analyses of the other images we present. For each of them, we provide a caption that identifies its origin and offers some data that will assist in interpretation.

Plates

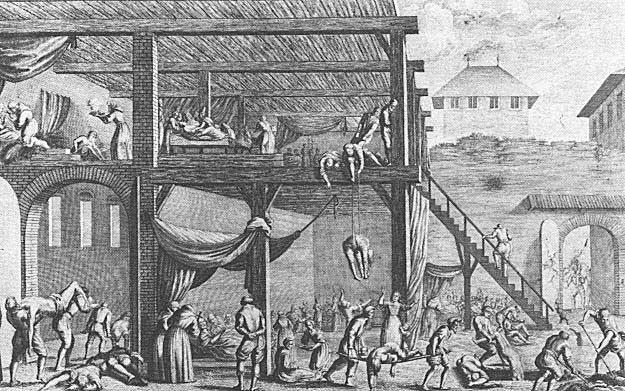

1. Plague Hospital. Sixteenth-century German engraving by

Jeremiah Wolff. The New York Public Library, Print Collection.

The original meaning of hospital was "place of rest." By the late Middle Ages,

hospitals in Western Europe had become institutions for the care of the infirm

and dying. During epidemics, buildings of various origins were transformed into

hospitals in order to isolate the sick from the healthy, care for the patients, and

ease their passage from life into the hereafter. A hospital was a place to rest and

die, not to be cured. In this engraving, a building at the edge of town has been

designated as a plague hospital. The sick are carried in through the gates at lower

right, and at various points in the print we can see patients being fed, cared for,

given last rites, and removed to the grave in the foreground before the same gate

through which they entered.

2. Hyacum et Lues Venera. French engraving, c. 1570, by Theodor

Galle, after Strada. The New York Public Library, Print Collection.

See the description of this engraving in the introduction to this article.

(Image on next page)

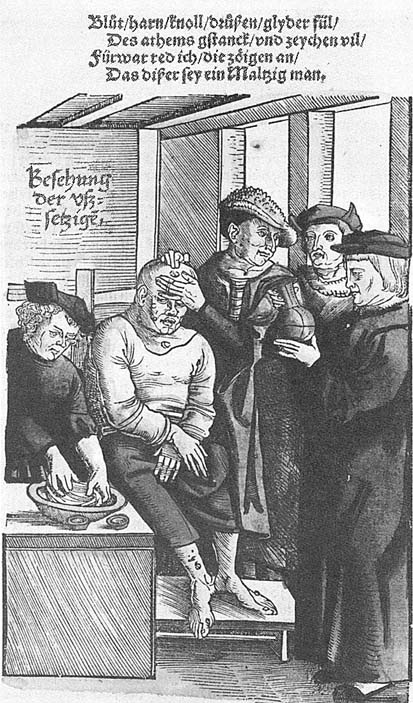

3. Examining a Leper. Early sixteenth-century German colored woodcut,

possibly Johannes Wechtlin. From Feldtbuch der Wundartzney (Strasbourg,

1540). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Ars Medica Collection.

This woodcut appeared in a field manual used primarily by military surgeons

and frequently reprinted. Didactic rather than illustrative, the woodcuts were

pictorial reports of medical procedures presented in Renaissance style. The use

of space is ordered and rational. The figures were simplified and idealized to

demonstrate proper medical practice. The quatrains above each drawing summarized

the medical knowledge appropriate for the procedure being illustrated. This picture

emphasized the medical obligation to treat lepers while it demonstrated the symptoms

of the disease. Four doctors examine a patient: One touches the patient's head while

describing the symptoms of leprosy in the quatrain (notably distension, stinking breath,

and obvious lesions), and the surgeon at the right holds a flask in order to demonstrate

the traditional diagnostic technique of uroscopy.

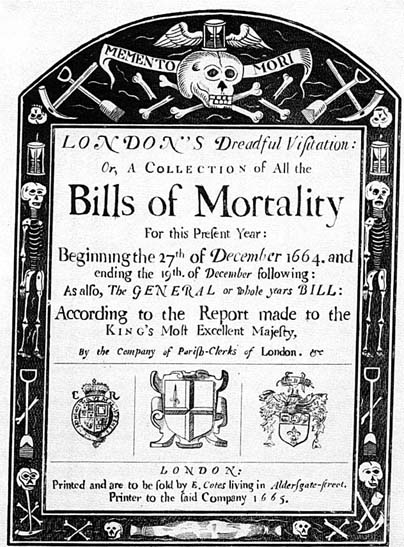

4. Frontispiece engraving for Bills of Mortality (London, 1665).

Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London.

By the seventeenth century some cities published records of the numbers

of deaths and their presumed causes. This volume dates from the Great

Plague of London in 1664. The memento mori embellishments on the

border—skulls, winged hourglasses, skeletons, picks and shovels—are

allegories. These conventional symbols allow viewers to contemplate death

while maintaining emotional distance from the gruesome realities of their

everyday lives. They also serve as reminders of the transience of life.

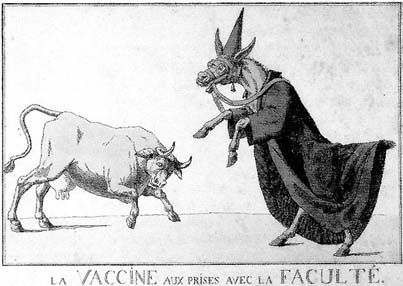

5. La VACCINE aux prises avec la FACULTÉ (Vaccine in Conflict with

Academic Medicine). Late eighteenth-century colored etching of the French

school. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Ars Medica Collection.

This etching satirizes the controversy over the merits of vaccination against

smallpox. The cow, defiantly poised for conflict, symbolizes the medical

practitioners and their lay supporters who embraced the potential of mass

vaccination. The donkey, dressed in academic robes and bearing the venerable

names of Hippocrates and Galen on its reins, represents the leaders of academic

medicine who attacked vaccination as a mad deviation from properly informed

medical practice. The conventions of the cartoon framed the issues of this debate

in concise terms for the public.

6. La Vaccine. French color lithograph, 1827, by Louis Leopold Boilly.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, Ars Medica Collection.

Boilly was well known for his genre portraits of people in all ranks of French

life. Here he depicts a household interior where vaccination is taking place.

The procedure is now a part of everyday life, rather than a source of controversy

as it was then.

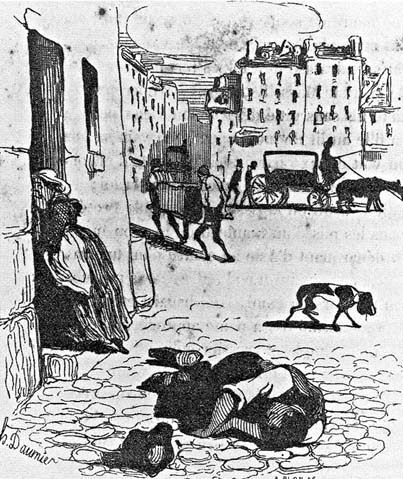

7. Cholera victim. Woodcut from Némésis médicale illustrée , recueil de

satires (Brussels, 1841) by Antoine François Hippolyte Fabre, after a

drawing by Honoré Daumier. National Library of Medicine, History of

Medicine Division.

This wood engraving translates a drawing by Daumier, the great chronicler

of Parisian life in the pictorial arts, into a printed image presenting the harshness

of urban experience in the mid-nineteenth century. During an epidemic, another

cholera victim has collapsed in the street and attracts no attention from other people,

not even from a dog. The speed and energy of Daumier's lines, which were maintained

in Fabre's engraving, present a powerful image of a familiar event.

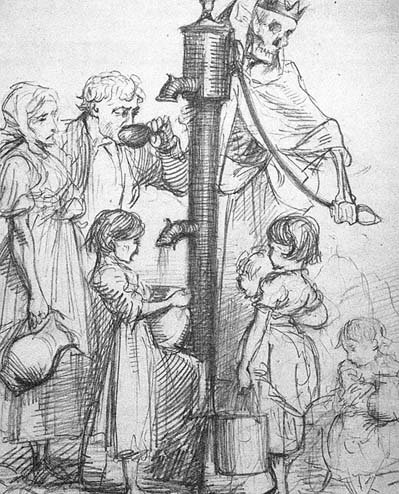

8. Death's Dispensary. English graphite on paper, c. 1866, by George John

Pinwell. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Ars Medica Collection.

This powerful drawing by a noted wood engraver and water colorist was a preparatory

sketch for an illustration published in the English magazine Fun during the outbreak of

cholera in London in 1866. By 1866 most physicians and public health officials were

convinced that cholera was communicated through the water supply. Pinwell's image,

which shows a skeleton figure of cholera working the handle of a pump, dispensing disease

to all who imbibe the contaminated water, conveys the horror of the public realization

that the population in 1866 might still unwittingly be exposing themselves to disease.

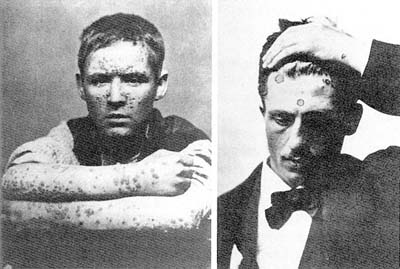

9. Photographic portraits of patients with syphilis. From George Henry Fox,

Photographic Illustration of Cutaneous Syphilis (1891). Stanley B. Burns, M.D.,

and the Burns Archive.

In the late nineteenth century many physicians embraced the new technology

of photography to document pathological anatomies. They appropriated for this

purpose the conventions of contemporary portraiture in drawing and painting.

These contrasting portraits depict the scourge of syphilis from two points of view.

The boy, photographed with his arms folded to show his lesions and looking directly

at the camera, is an innocent victim of heredity. The man, depicted in formal clothes

with his upraised arm calling attention to the lesions on his forehead, his eyes averted

from the camera, would have been recognized by contemporaries as a rake.

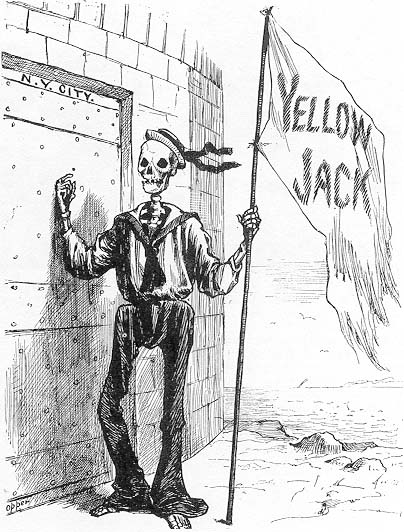

10. Yellow Jack. Engraving from Frank Leslie 's Illustrated Newspaper ,

21 September 1883. New York Academy of Medicine.

In this cartoon, Death, dressed in the uniform of an Italian sailor, brings yellow

fever—popularly called Yellow Jack—to New York's door. The cartoon's social and

political implications during a decade when millions of immigrants arrived in

American ports needed no caption. A century later, when the authors exhibited this

cartoon in New York City, it was widely reprinted, presumably because of its direct

analogy with the AIDS epidemic.

11. Le Roi Peste (King Plague). Belgian etching, 1895, by James Ensor.

National Library of Medicine, History of Medicine Division.

James Ensor, painter and printmaker, combined an understanding of the tragic mystery

of nature with malevolent humor. For most of his creative life he was obsessed with the

specter of death, depicting it in myriad social and personal situations. In this etching, he

was inspired by "King Pest," a story written by Edgar Allan Poe, whose work fueled the

Symbolist-Expressionist movement in Europe. In an undertaker's room where a skeleton

hangs from the ceiling, King Pest the First carouses with his ghoulish council. In literature

and the fine arts, plague remained a powerful theme in the late nineteenth century, even as

its epidemiological significance diminished.

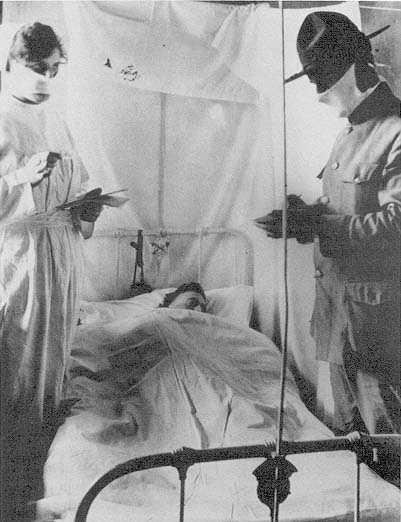

12. Army camp, New York State. By an unknown photographer, 1918.

American Red Cross.

An influenza epidemic claimed more than half a million lives in Europe and America

in 1918-1919. Photographers depicted medical care during the epidemic with conventions

that had been changing rapidly for two decades—change that was accelerated during

World War I. According to these newer conventions, photographers moved closer to their

subjects in order to communicate stories about human relationships. Unlike the figures in the

portraits in fig. 9, the patient here is shown with a physician and a nurse who are

working—protected from contagion, they hoped—by face masks.

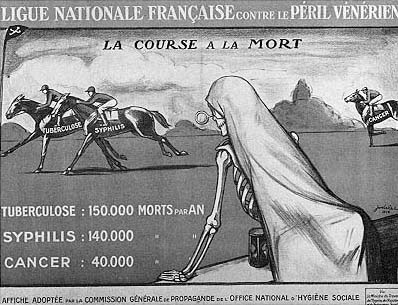

13. La Course à la Mort (The Race to Death). French colored lithograph,

c. 1926, by Jodalet. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of William H. Helfand.

This powerful propagandistic lithograph was published by the National Office of Social

Hygiene as part of the public campaign of the National French League against Venereal

Disease. Using popular imagery rather than conventions of high art, Jodalet places us at

the rail along with a macabre personification of death, draped in a shroud, watching the

progress of this modern apocalyptic race through a magnifying glass. We are reminded of

the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, who trample the rich and the poor alike. The three

horsemen here—tuberculosis, syphilis, and cancer—are, it would seem, about to be joined

by a mysterious fourth before the hourglass (a memento mori image, as in fig. 4) runs down.

14. Leprosy from "A Man of Mercy." Photograph, 1954, by W. Eugene

Smith. Black Star.

This photograph of a man suffering from leprosy presents with clarity and directness the

harsh reality of a disease that, although associated with the Middle Ages, remains widespread

today. Rather than focusing on the patient, Smith depicts the disease and the deformity in a

way that initially appears to be clinical. Smith was one of the foremost photojournalists of his

generation, however, and he took this photograph to illustrate a Life magazine essay on the

work of Dr. Albert Schweitzer. Thus, the interplay of the leper's feet and the arm of the unknown

person above him creates a story that suggests truth, power, and humanity. The image is beautiful

and haunting, despite its subject matter.

Image not available.

15. Patient with AIDS, Ken Meeks, being cared for by a friend. Photograph,

1986, by Alon Reininger. Contact Press Images.

This image is analyzed in the introduction to this article.

Notes

1. Diane R. Karp et al., Ars Medica : Art , Medicine and the Human Condition (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1985); Daniel M. Fox and Christopher Lawrence, Photographing Medicine : Images and Power in Britain and America since 1840 (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1988). [BACK]