Always Outside

If the identity outside the literal depiction on the Narmer Palette is simultaneously the maker and the viewer—that is, the artist—then these are positions not only of the actual artist of the work, whoever he or she might have been, but also of the real ruler. Looking over his shoulder to take note of the ruler standing behind him as he produced the representation of the ruler coming up behind his enemy, the artist—along with the figures he drew—is the ruler's representative in the scene of representation. Other works of the early First Dynasty, while fragmentary, seem to advance a literal depiction of the ruler as maker into the depicted scene; his identity as the one who sees had already been well established by the chain of replications (Figs. 25, 26, 28, 33, 38).

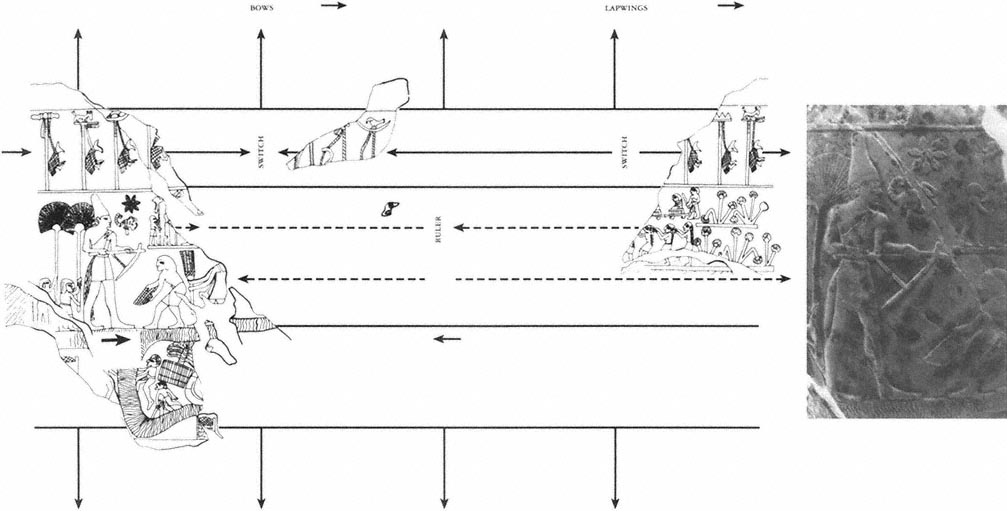

In the image on the carved mace head of the so-called King Scorpion (Fig. 52), probably to be dated roughly to the time of Narmer, the ruler makes the fields of Egypt and, extending the depiction into the metaphorical domain, presumably Egypt's abundance and prosperity as well. The figure of Scorpion is singled out, first, by his size—he is the tallest in the composition; second, by the "royal" rosette and scorpion sign in front of his face, apparently the only such label in the composition; and third, by a narrative device we cannot be surprised to discover, considering how other images in the chain of replications have been put together. The wide band of depiction running around the middle portion of the mace head is divided internally into two (and at points three) stacked registers. The only exception is the figure of Scorpion, facing to the right in the surviving piece of the mace head, who spans the entire band from top to bottom. In the top register of the remaining piece of the central band, figures are oriented as moving away from Scorpion, and in the bottom, as

moving toward him. The switch in direction—where figures moving away must be coming together and figures moving toward must be proceeding outward—is undoubtedly made on exactly the other side of the mace head, in a passage of depiction that can be viewed only when the viewer is not viewing the figure of the ruler opposite it.

But what should appear in this other, exactly opposite position—predictably behind or on the other side—but another figure of the ruler? Although the mace head is almost completely missing for this segment of the image, a surviving fragment of a rosette emblem (not the same as the one used to label the ruler in the main surviving piece of the object) indicates that Scorpion was probably depicted here as well. Presumably facing to the left, he must have been engaged in an activity involving the women of the household, being carried toward him (one carrier and two women have survived), as well as rejoicing women (four surviving figures are visible) and advancing retainers with standards (three surviving figures are visible).

If this interpretation is correct, the portion of the image that survives on the mace head is the "other side" of the "opening" of the visual text—or, more accurately, the depictions of the ruler on both sides of the mace head are the "opening" of a pictorial narrative text, viewable in both directions, of which the ruler opposite is on the other side. In viewing this image by turning the mace head, the two depictions of the ruler are also the "middle" point reached on the two strips of the central band wrapped around the object. Starting with one ruler, we pass by the other ruler in the process of turning the mace head all the way around to the beginning again. In the top band of the image, above the figure of each ruler, the standards with hanging elements—lapwings (possibly the hieroglyph for the people of Egypt) and bows (perhaps the "nine bows" that later symbolize the foreign enemies of Egypt)—face in the direction the ruler is facing. Thus the lapwings hanging from standards by ropes strung around their necks make a switch in direction, with the birds replaced by hanging bows (and vice versa), precisely—in the most plausible restoration I offer here—between the points where the two rulers are placed.

In the portion of the image that survives, Scorpion wields a hoe, the same implement used elsewhere in early dynastic image making to depict the breach-

Fig. 52.

Mace head of King Scorpion: carved limestone mace head from Main Deposit at Hierakonpolis, early First Dynasty. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Detail of principal

figure of King Scorpion (photo courtesy Ashmolean Museum, Oxford); line drawing of surviving surfaces (corrected after Smith 1965) and suggested structure of the image.

ing of enemy fortresses (see Fig. 53, right). Here he is cutting an irrigation canal, indicated along the bottom register of the central band by a channel of water that forms the ground line for his figure and those of several others. Two bearers approach "from the right" to stand before him, preparing to sweep up and carry off the dirt.[5] Two fan bearers come up behind him "from the left" (possibly emerging from the building depicted behind them, according to a recent restoration; Millet 1990: 59) to shade him from the sun. The ruler has the White Crown of Upper Egypt, the tunic, and the tail he wears on the Narmer Palette (Fig. 38); the locality seems to be specified as Papyrus Land.

In the register below the ruler's ground line and to the right (that is, coming into view from the right if the mace head is turned around left behind right), the ruler's sacred bark—only its prow visible—sails on the river, coming from the direction of the scenes now completely lost. Thus as the mace head is turned around to the left, moving "to the right" away from the figure of the ruler, the boat "sails toward" the viewer. (Since the boat presumably bears the ruler, as one figure of the ruler disappears from view, it is as if the other figure—on the other side of the palette—is being transported into view; as always, the narrative is in the motion.) In its progress the boat will pass by or between two cultivated plots. The right-hand plot in the preserved portion of the image is inhabited by a hoeing farmer, below, and another man, above, who seems to thrust his hands into the river. The left-hand plot, now badly damaged, probably contained the same two men; the top figure, thrusting his hands into the water, is still preserved. All these characters may be defeated, bearded enemies of the ruler put to work or settled on the land. Although it is not possible to understand the arrangement of the lower register, it seems that it was divided by the waterlines, and possibly other devices, into at least two and probably more episodes concerning the life of the countryside. The figures seem to be repeated from one zone to the next, as is a round-topped building. The register was probably arranged to establish a series of "befores" and "afters," or of preconditions and consequences, of the ruler's actions as they appear in the central band above it.

In sum, the image as a whole—top band, internally divided central band, and bottom band—divides into two principal movements, separated in the

central band by the register line that runs around the middle of the mace head. The two movements always go in opposite directions as far as we can tell from any single view of the image stretched around the mace head. When the top portion of the image is moving away from Scorpion "to the right," the bottom portion is moving toward him "to the left," and when the top portion is moving away from him "to the left," the bottom portion is moving toward him "to the right." The two figures of Scorpion, opposite one another in the image and each oriented in reverse direction from the other, span these two movements, whose "switch" is not visible when either figure of the ruler is being viewed. Thus, as in the other images in the chain of replications, the ruler is always outside, coming around and behind that which faces toward him and that which faces away from him. This much of the general structure of the image is clear. Unfortunately its metaphorical and narrative content remains obscure; because only about one-third of the whole has survived, we cannot say how the several episodes fitted together.[6]

As the awkward drawing of Scorpion's hands and forearms suggests (there may be substantial recutting here), the artist struggled to position the main handle of the ruler's hoe almost exactly parallel with the ground line. This formal relation in the text of the image is crucial in the general metaphorics. It is the ground line itself that is wielded by the king, produced by him from the land of Egypt and—in continuing or "shooting out" from the hoe and around the mace as the viewer turns it—supporting the register of his rejoicing retainers and standards. The ruler makes the very order that canonical representation finds in the world.

This order is presented also in both early dynastic and canonical image making, as that which the ruler possesses as his estate (Figs. 1, 2). The Libyan or Booty Palette fragment (Fig. 53) preserves roughly the bottom third or half of an image perhaps derived from late prehistoric images as an independent symbol of their metaphorics of the ruler's victory, and now probably of state rule. A missing top register on one side (top )—we cannot tell obverse from reverse because the cosmetic saucer is absent—might be restored as prisoners being marched to the right by the ruler's retainers (for example, like the scene on the Beirut Palette fragment [Asselberghs 1961: fig. 183; Davis 1989:

Fig. 53.

Libyan or Booty Palette: carved schist cosmetic palette,

early First Dynasty. Courtesy Cairo Museum.

fig. 6. 12]); remains of human feet are visible at the edge of the break. Although a figure of the ruler might be restored in this register, he would presumably have to be placed in the center or on the left side so as not to violate the general organization of late prehistoric images, in which the ruler and the ruler's representatives never face "out" of the scene but are always coming into it. All the figures on the palette, however, should probably be "read towards the left in accordance with the orientation of Egyptian writing" (Terrace and Fischer 1970: 21). As we would expect, then, considering the replicatory revisions of the Narmer Palette, this palette exemplifies an emerging canonical revision of the order of late prehistoric image making.

Below this passage of depiction, whatever it presented, fortified cities—inside each, town-name hieroglyphs accompany small rectangles apparently indicating buildings—are breached by representatives of the ruler, including a falcon (top row) and a lion, a scorpion, and falcons on standards (bottom row). In its metaphorics the scene is related, on the one hand, to the image of ruler-as-bull breaking down the enemy citadel on the Narmer Palette (Fig. 38) and, on the other, to the ruler-as-wielder-of-the-hoe, as "maker" of Egypt, on the mace head of King Scorpion (Fig. 52).

On the other side of the palette (bottom ) three registers of animals survive—from top to bottom, bull oxen, donkeys, and rams, all males of their species. The image on this side might originally have included another register or two in the missing piece. There are four beasts in each surviving row of animals, with the exception of the last. The creatures are usually interpreted as booty taken by the ruler from plundered towns in the "olive-tree land" symbolized by the olive trees and "Tjehenu" sign (= western delta, Libya) in the bottom zone on this side of the palette (Vandier 1952: 592). Like the animal-rows motifs produced much earlier in the chain of replications, but separated from them by the complex set of disjunctions we have surveyed, the animals march along ground lines drawn from one edge of the scene to the other, eliminating, as they go, the possibility of a sideline or another ground for humankind and nature. This image has "tamed the unruly mob of the early palettes (although it seems to have robbed every creature of some of its mysterious potency)" (Groenewegen-Frankfort 1951: 20).

Only the young ram at the end of the line in the bottom row—observed last if the image is viewed like hieroglyphic writing from right to left—turns back its head to look outside the depicted scene it inhabits as the king's estate. This figure reminds us (would any contemporary viewer have remembered?) of one of the commonest devices of late prehistoric image making—namely, the creature pursued by what it does or does not see about to catch up with it. But what could be behind this ram but a register line, the continuous, endless ground of the ruler? Or does the register line wrap around the palette—where in fact it disappears in this position—and the ram gaze back into a wild place where the register line cannot be found? The ambiguity is surely inherent and unresolved. The maker of the palette, standing in line facing the ruler like everything and everyone else, did not absolutely intend or fully anticipate how his ram would function. He simply ran out of space toward the bottom of the tapering palette and was forced to squeeze one figure in by drastically scaling down and shortening its body and turning its head back. And yet this slip, or resistance, of the maker plotting the ground figures some possibility of wildness within the unalterable armature of canonical representation. It constitutes as possible the continued presence, for canonical Egyptian art, of the late prehistoric scene of representation that is now literally behind and completely outside it.

The possibility of wildness is only that, for the actual person of the ruler of Egypt is still outside the scene of representation and in the canonical tradition will never be within it. His "real" appearance outside—as much as his represented appearance within—the literal depiction masks the way he continues to stand beside and behind. He is merely represented by that apparently real body with its composing blow of canonical figuration—that is, by the person, action, and gaze of the artist. The ruler himself, as ruler of the entire scene of representation, remains outside. He continues to designate how he will be seen—namely, precisely as the source of the representation he appears to inhabit from any angle or from all directions and about whom such a representation is naturally made. The artist who, as the representative of the ruler, enters a representation that depicts the king entering an unseeing nature can be nothing more than another nature entered by the ruler. The artist is "nature" carried to

the second power, or to as many powers as might be nested within one another; the artist is part of the scene of representation as it is always framed by a final, absolute power outside it. That power is absolute in the world it attempts to guarantee by putting forward this very representation of it. The ruler remains beyond representation—masks his own blow—until his wildness can be entered as a nature by one who has his or her own place outside the ruler's representations.

Disjunctive as it is, a movement has been completed—a series that has taken us through images none of which can stand alone (or as a whole, a beginning or an ending), each subsisting only in terms of what is behind and outside it. From the Oxford Palette (Fig. 26) to the Narmer Palette (Fig. 38)—a temporal and spatial slice of the chain of replications—the deadly forces of humanity and nature have completely traded places, shifted ground, twisted about, absorbed into each other, and advanced from outside to inside and inside to outside. Throughout, the ruler—father, hunter, matriarch, warrior, king—is forever in advantage by the very fact of being behind, the only one to approach always obliquely behind a mask with the other always failing to see him there. Unseeing nature, which cannot represent, does not design a place for the ruler; the ruler designs a place for it—that is what defines him as a ruler, absolute within the temporary reign of uncontested representation.

On the Oxford Palette the wild dogs face one another and clasp paws, while below them the masked hunter stands near the sidelines playing his flute. On the Narmer Palette the heraldic cows turn outward to face the one who looks at the entire scene: the ruler himself, never literally depicted in the scene of his mastery but only figured there as the condition of its composition. And within the depicted scene, at right angles to the person viewing him as his or her self, his represented natural double—the figure of the ruler smiting his enemy—has exchanged his mask and flute for crown and mace.