Preferred Citation: Lutgendorf, Philip. The Life of a Text: Performing the Ramcaritmanas of Tulsidas. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft796nb4pk/

| The Life of a TextPerforming the Ramcaritmanas of TulsidasPhilip LutgendorfUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1991 The Regents of the University of California |

To Meher Baba, the Singer,

and

For My Parents

Preferred Citation: Lutgendorf, Philip. The Life of a Text: Performing the Ramcaritmanas of Tulsidas. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft796nb4pk/

To Meher Baba, the Singer,

and

For My Parents

Acknowledgments

The company of good people is the treasury of all virtues.

I salute them with affection, and with words.

1.2.4

The poet Tulsidas wisely commenced his epic with a lengthy passage that has come to be known as the "obeisance to all beings" (samasti[*] vandana )—an effective way of discharging the burden of gratitude every author feels. If the truth be told, I feel scarcely less comprehensive a debt, but I will refrain from invoking planets, rivers, and mountains (although they helped too—especially the Ganga and the Himalayas) and will simply cite some of the many friends and teachers whose assistance was invaluable in the research and writing of this book.

At the University of Chicago, Colin Masica first introduced me to the pleasures of the Ramcaritmanas ; Kali C. Bahl guided me in my initial reading and recitation and also first suggested a research project on the epic's contemporary performance. Both served as readers of my first draft, together with Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty and A. K. Ramanujan, who likewise contributed much insight, encouragement, and humor. Among many others at Chicago who deserve thanks, I must single out Edward Dimock (a teacher and friend for more than fifteen years), Susanne and Lloyd Rudolph (mentors and good neighbors in India), Joan Erdman and David Gitomer (each of. whom helped me sort out troublesome passages), Maureen Patterson, and C. M. Naim. Thanks too are due to administrators Katherine Mosely and Shirley Payne. I owe a special debt to Mircea Eliade, an undergraduate mentor and a lasting example of humane and meaningful scholarship.

My study of Hindi was supported by fellowships from the United States Department of Education and the American Institute of Indian Studies; I would like to thank, at the Delhi office of the latter institution, Pradeep Mehendiratta and his staff, and my Hindi instructor, Santwana Nigam. The field research for this project was made possible by a Fulbright-Hays Fellowship; special thanks for assistance are due to Alice Brookner at Chicago and Sharada Nayak and her staff in New Delhi. In Banaras I owe gratitude to Dr. Tribhuvan Singh, my academic adviser in the Hindi Department at Banaras Hindu University; the Mankhand family, who cared for me through my first Ramlila ; and the staff of the A.I.I.S. Center for Art and Archaeology, especially Mr. V. R. Nambiar and his hospitable family; also to Dr. Virbhadra Mishra of the Sankat Mochan Foundation, and Virendra Singh and his family. In Mussoorie I owe thanks to Bill Jones and Hugh Bradby of the Woodstock School, and to Chitranjan Datt and the staff of the Landour Language School. Others in India who offered special help and inspiration were the families of Keki Desai and Kusum Singh in Delhi, Padma Srinivasan in Bombay, and Eruch Jessawalla, Mani Sheriar Irani, and other friends in Ahmadnagar, Maharashtra.

Profound thanks must be offered to the numerous Ramcaritmanas reciters, singers, expounders, and devotees in Banaras, Ayodhya, Chitrakut, and elsewhere who shared with me their knowledge and experience of their beloved epic; many of them are cited in the pages that follow. Here I would single out the special assistance given by Shrinath Mishra of Banaras; Baba Narayankant Tripathi and Ramnarayan Shukla of the Sankat Mochan temple; Ramkumar Das and Sacchidanand Das of Mani Parvat, Ayodhya; and Ramkinkar Upadhyay. Dr. Bhanuprasad Mehta gave timely help at the Chitrakut Bharat Milap, and Dr. Bhagavati Prasad Singh, retired head of the Hindi Department at Gorakhpur University, generously shared his extensive knowledge of the Ram bhakti tradition. Ramji Pandey, the chief Ramayani of the Ramnagar Ramlila , was my guide and amiable companion there and on pilgrimages to Ayodhya, Prayag, and Chitrakut. Also in Ramnagar I owe special thanks to the maharaja of Banaras, Vibhuti Narayan Singh; Giorgio Bonazzoli of the Kashiraj Trust, and in the tiny shop at the corner of the fort—the jovial vendor of the city's best tea, who opened his home to me on coronation night. Back in Shiva's city I salute my special guide in field research—and one to whom its evolution owes much—Chandradharprasad Narayan Singh, an inspiring example of connoisseurship mingled with devotion. To all such true rasiks of the epic, this work is especially offered.

The writing of the dissertation that formed the basis for this book was supported by a fellowship from the Committee on Southern Asian Studies at the University of Chicago. Apart from the members of my dissertation committee, three patient readers offered special assistance and encouragement: John Stratton Hawley, Linda Hess, and Frances Pritchett. Linda Hess and Richard Schechner generously shared with me their rich knowledge and experience of the Ramnagar Ramlila . Nita Kumar and Scott Marcus offered assistance on specific aspects of Banarsi culture; I also benefited from the insights and encouragement of Thomas Coburn, Sandria Freitag, William Graham, and H. Daniel Smith. I owe much, too, to my colleagues at the University of Iowa—especially Sheldon Pollock, Paul Greenough, Maureen Robertson, and Thomas Rohlich. Thanks are also due to Todd Papke of the Weeg Computer Center for technical assistance in the production of the manuscript. Lynne Withey and Betsey Scheiner of the University of California Press merit special thanks, both for their encouragement and for their editorial labors in bringing this text to life. I would add that the warm friendship of many whom I have cited here has meant as much to me as their substantial contributions to my research.

Finally, I must thank those whose tangible and emotional contributions have been even more sustained: my parents on both sides of the family, Gary and Helen Lutgendorf and Mike and Dorothy Donner, and my wife and daughters, Susan, Mira, and Claire. Susan Kerri Lutgendorf (at various times) enjoyed and endured the long adventure of my language study and field research, which included listening to me recite the Ramcaritmanas at odd hours and nursing me through a tedious illness in what we sometimes called the "City of Blight"—all the while helping to raise two children and postponing her own important work in counseling and healing. Her companionship has been vital to my research and to my life.

A Note on Transliteration

All italicized technical terms from Hindi and Sanskrit and the titles of literary works have been transliterated according to the system followed by the Library of Congress, with the exception that for Hindi words the medial and final vowel a , which is usually not pronounced, has been omitted from most words (thus Ramcaritmanas rather than Ramacaritamanasa ). However, for certain words that end with conjunct consonants, the final vowel has been retained (bhakta ), as native speakers often add a slight vowel in such cases and this form may likewise be more readily pronounced by readers. The final vowel has also been retained in a few words that have become familiar to English readers in Sanskrit-derived transliterations (karma, dharma, yoga). In transliterations of medieval Hindi verses, however, all vowels are shown, since they are normally pronounced for metrical reasons. The nasalization of a final vowel (anunasika ) is indicated by m[*] (mem[*] , gosaim[*] ).

For readability and to avoid an excess of diacritics, a different approach has been adopted for proper nouns. These are given without diacritics and with the substitution of sh for both the consonants

they themselves transliterate them. As noted above for technical terms, so in the case of names, final conjuncts have generally been joined to a short vowel (Mishra, Shukla); so too the names of certain deities that may be familiar to readers in such spellings (Shiva, Garuda). The names of castes and dialects follow the same rules (Brahman, Kshatriya, Khari Boli). For those who wish to be certain of pronounciation, an appended glossary provides proper nouns with diacritics.

Throughout this book, the term "Ramayan" is used to designate the broad tradition of retellings of the Ram narrative, and in occasional references by Hindi speakers to their Ramayan, that is, the Ramcaritmanas ; the Sanskritic transliteration (Ramayana[*] ) refers only to Sanskrit works so titled.

One

The Text and the Research Context

The nature of this Manas, how it came to be, and to what end it was manifested to the world—I will now narrate all these matters, remembering Uma and her Lord.

1.35

Introduction

Anyone interested in the religion and culture of Northern India sooner or later encounters a reference to the epic poem Ramcaritmanas and its remarkable popularity.[1] This sixteenth-century retelling of the legend of Ram by the poet Tulsidas has been hailed "not merely as the greatest modern Indian epic, but as something like a living sum of Indian culture," singled out as "the tallest tree in the magic garden of medieval Hindu poesy," and acclaimed (by the father of Indian independence, Mahatma Gandhi) as "the greatest book of all devotional literature."[2] Western observers have christened it "the Bible of Northern India" and have called it "the best and most trustworthy guide to the popular living faith of its people."[3]

[1] All translations from the Ramcaritmanas are mine except where otherwise indicated. Numbers refer to the popular Gita Press version edited by Hanuman Prasad Poddar. For an explanation of the numbering system, see below, p. 15.

[2] The first quotation is from R. C. Prasad, in his introduction to the revised edition of Growse, The Ramayana[*]of Tulasidasa , v; the second is from Smith, Akbar, The Great Mogul , 417; the third is from Gandhi, An Autobiography , 47.

[3] E.g., Macfie, The Ramayan of Tulsidas ; the second phrase comes from Growse, The Ramayana[*]of Tulasidasa , xxxviii.

Such remarkable notices may arouse one's curiosity, first of all, to read the text—although here the English-language reader may be daunted by the fact that (for reasons to be discussed below) Tulsidas's great epic fares rather badly in translation. Beyond that, a student interested in the popularity and impact of this remarkable work has had to be content with a literature consisting primarily of textual studies that, despite their undoubted contributions to an understanding of the origin, structure, and meaning of the epic, shed little light on its interaction with its audience—an interaction that has never been primarily through the medium of the written word. Indeed, it seems ironic that a text so often cited as a popular and living tradition has received so little study as such, apart from a handful of treatments of Ramlila folk dramas, the most obviously "theatrical" genre of Ramcaritmanas performance. The present study, which grew out of one reader's encounter with the text and increasing curiosity about its living performers, seeks to fill this lacuna by investigating a wide spectrum of performance genres that utilize the epic, including traditions of public and private recitation, folksinging and formal exposition, as well as the more familiar Ramlila pageants. Approaching the text from the perspective of its performance, it will suggest that, in the audience's experience, the two are essentially inseparable.

Since its underlying approach will be to treat the Ramcaritmanas as, in S. C. R. Weightman's admirable phrase, "a religious event"[4] and as a living—hence necessarily changing and evolving—presence in North Indian society, this study will also be concerned with the historical development of the performance genres that it treats. This is problematic, since written source materials are meager, and oral history—although richer—cannot be relied on for accuracy. Yet a historical perspective is all the more necessary given the tendency of many within the Hindu tradition to assert the hoary antiquity and static changelessness of their practices, and of some Western scholars to accept such pronouncements uncritically. The living tree of Hinduism may indeed have deep roots, but it is constantly putting out new branches as well as occasionally shedding dead leaves, and although many of the performance genres described here had ancient precursors, their evolution and present popularity reflects, as will be seen, specific social and historical developments of the comparatively recent past.

Even a study of text-in-performance must necessarily begin with the text—itself an essential context for understanding its performance. The

[4] Weightman, "The Ramcaritmanas as a Religious Event," 53-72.

present chapter is intended to provide the general reader with background information necessary for an appreciation of the performance genres to be examined in succeeding chapters. To this end it touches on a number of potentially vast subjects: the history of the Ramayan tradition, the life and works of Tulsidas, and the metrical and narrative structure of the Ramcaritmanas —even though, in some cases, exemplary studies or even whole literatures on these topics already exist. For a study based primarily on field research, other contexts must also be delineated: conceptual, methodological, and geographical; hence this chapter also introduces some of the concepts that underlie the study, places them in reference to other recent research, and outlines the structure of the investigation to follow. It concludes with a brief introduction to the city of Banaras and its importance as a setting for the performance of the Tulsidas epic.

Tulsidas and the Ramayan Tradition

The Ramcaritmanas is an original retelling, in a literary dialect of Hindi, of the ancient tale of Prince Ram of Ayodhya—a story that exists in countless variants both within and beyond the Indian subcontinent and represents one of the world's most popular and enduring narrative traditions. The Ram legend has not only given rise to hundreds of literary texts, including several that rank among the masterpieces of world literature, but has also flourished for at least two millennia—and still flourishes today—in oral tradition.

The most influential early text of this tradition is the one called Ramayana[*] ; indeed, in India this name has come to be used as a sort of genre name for all texts of the tradition and even as a colloquial label for any long narrative (as in the Hindi expression "to narrate a Ramayan"—i.e., to go on at great length about some matter). Traditionally attributed to the poet Valmiki, this Sanskrit epic of some 24,000 couplets is thought to have been composed within the first few centuries before the beginning of the Christian Era[5] . Internal evidence suggests that a considerable portion of it may indeed have been the work of a single author, but nothing is known of Valmiki as a historical figure. Popular legend depicts him as a lowborn robber who was transformed into a sage by the grace of Ram and who wrote his narrative during his hero's own lifetime, in the Treta Yuga or second aeon of the current cosmic cycle, which Hindus commonly place in the extremely remote

[5] On the dating of this text, see Goldman, The Ramayana[*]of Valmiki : Balakanda[*] , 20-23. Note, however, that many scholars disagree with Goldman's early attribution.

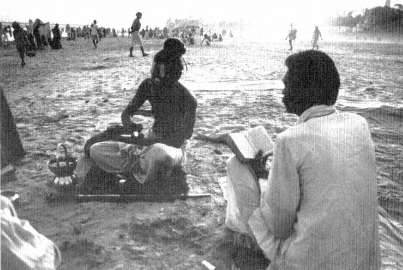

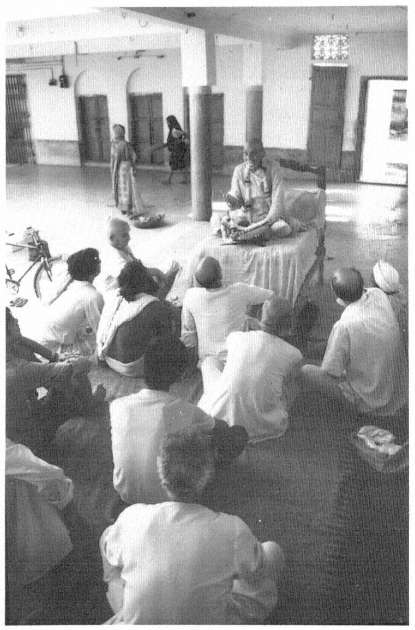

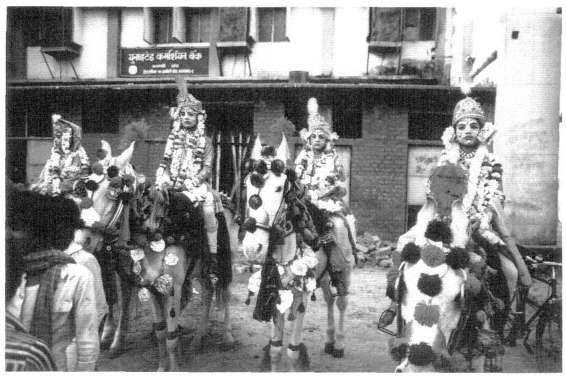

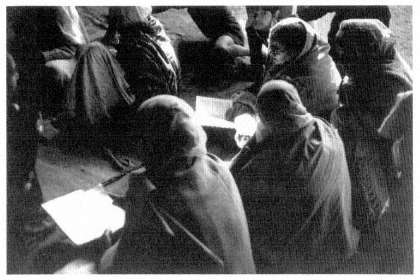

Figure 1.

A pilgrim recites the Manas for a sadhu, in Ayodhya at dawn on

Ram's birth anniversary (Ram Navami)

past—"nine lakh [900,000] years ago." Valmiki is thus hailed by later tradition as adikavi —the first poet, the inventor of the influential sloka meter and the mentor of all later poets, especially those of the Ram narrative tradition.

Although the Sanskrit epic exerted a great influence on later retellings of the Story, the vernacular "Ramayans" that began to be produced from roughly the eleventh century did not offer simple translations of Valmiki's story, but rather reinterpretations of it. Because the specific transformations of the story through various texts have been traced by literary scholars,[6] it suffices here to note that the most important trend in the development of the tradition was the reinterpretation of the narrative in the light of the bhakti (devotional) movement, which effected the transformation of the epic's protagonist from an earthly prince with godlike qualities of heroism, compassion, and justice, to a full-fledged divinity—or rather, the divinity; for in North India today the word Ram is the most commonly used nonsectarian designation for the Supreme Being.

The bhakti movement, in significant contrast to the earlier southward penetration of Aryan Sanskritic culture, appears to have begun in

[6] See, for example, Bulcke, Ramkatha : utpatti aur vikas ; Whaling, The Rise of the Religious Significance of Rama .

South India and slowly spread northward. Although certain of its influential texts were composed in Sanskrit, the movement was characterized by a preference for local languages, reflecting a concern to make its teachings accessible to the widest possible audience, irrespective of caste or class. The earliest texts associated with this new orientation, the hymns of the Vaishnava Alvars and the Shaiva Nayanmars, were composed in Tamil, the Dravidian language spoken near the southern tip of India. The first major vernacular Ramayan was also in Tamil: the Iramavataram of the c. eleventh-century poet Kampan, which remains the best-known Ramayan in Tamil-speaking regions.[7] Already in Kampan's version, Ram as the earthly incarnation (avatar ) of the supreme lord Vishnu retained his divine qualities of omniscience and omnipotence, so that his entanglement in the plot became merely a matter of appearance—or as the tradition would say, of lila : a self-staged divine "sport." Likewise, his beloved wife Sita had acquired many of the titles and attributes of the great goddess, mother of the universe, and her inviolability had become such a matter of principle that the poet had to concoct the device of having her demon abductor scoop up the plot of earth she stood upon, lest the touch of his hands defile her.

Kampan's epic was followed by the c. thirteenth-century Telugu Ramayana[*] of Buddharaja and by the fourteenth-century Bengali epic of Krittibasa. But even by the middle of the sixteenth century, there was still no major Ramayan in any of the dialects of the central Gangetic plain—the region that, ironically, was the geographical locus of the Ram legend. The story remained widely known and was told and retold in Hindu communities; its Sanskrit versions continued to be studied and commented on by members of the religious elite and expounded by them to wider audiences. But it may well reflect on the conservatism of this elite that no major literary rendering of the story had been made in the "impure" language of the people, even though such versions had long won acceptance further to the south and east.

The birthdate of the man who was to compose the Hindi epic of Ram—the poet Tulsidas—cannot be fixed with certainty, but many scholars have settled on 1532 as a likely year.[8] An unresolved and more emotional debate has concerned the poet's birthplace, with no less than seven places in present-day Uttar Pradesh and Bihar states vying for the

[7] For a partial English translation, see Hart and Heifetz, The Ramayana[*]of Kampan .

[8] Gupta, Tulsidas , 138-40; in English see the same author's "Biographical Sketch," in Nagendra, ed., Tulasidasa: His Mind and Art , 64. F. R. Allchin, however, favors a birthdate of 1543; see the introduction to his translation of Kavitavali , 33.

honor of claiming Tulsidas as native son.[9] Most modern accounts of Tulsi's life are based on slender internal evidence from his poetry supplemented by two controversial accounts attributed to contemporaries[10] and by later devotional hagiographies. In several apparently autobiographical verses in the Kavitavali and Vinay patrika —works thought to belong to the poet's old age—Tulsi refers to early abandonment by his parents (traditionally attributed to his having been born during an unlucky astrological conjunction) and to a childhood of loneliness, hunger, and pain, from which he was apparently rescued by a group of Vaishnava sadhus who gave him his first lessons in devotion to Ram, the "purifier of the fallen."[11] Yet it is thought that Tulsi himself did not become a sadhu at once but underwent a period of traditional Sanskrit education, probably at Banaras, and then returned to his native village to marry and live the life of a householder until a personal crisis caused him to renounce home and family. His subsequent wanderings took him to Ayodhya, Ram's birthplace and capital, and later to Banaras, where he settled, composed most of his major works, and died at an advanced age—probably in 1623.

The bare framework of this probable biography has of course been richly embellished by the hagiographic tradition. One of the best-known legends concerns Tulsi's decision to renounce worldly life, which is said to have been precipitated by his infatuation for his wife, Ratnavali. Unable to bear her absence while she was visiting her parents, Tulsi is said to have braved a rain-swollen river to reach his in-laws' house, only to receive, on arrival, a stinging rebuke from Ratnavali in the form of a couplet that has become proverbial.

This passion for my flesh-and-bone-filled body—

had you such for Lord Ram, you'd have no dread of death.[12]

These words are said to have opened Tulsi's inner eye and effected his conversion into a lifelong devotee of Ram, and so Ratnavali is some-

[9] Gupta, Tulsidas , 140-61; "Biographical Sketch," 65-77.

[10] These are the Mulgosaim[*]carit , attributed to Benimadhav Das (d. 1643) and the Gautamcandrika of Krishnadatta Mishra, supposedly composed in 1624; both were discovered only in the twentieth century. The former is widely regarded as spurious; the latter has been cautiously accepted by some scholars. For a brief discussion, see Gopal, Tulasidas , xii.

[11] See Kavitavali 6.73, 7.57, and Vinay patrika 275.1-3. For discussion of these verses, see Allchin's introduction to his translations of both works, Kavitavali , 33-34, and The Petition to Ram , 31-32. "Purifier of the fallen" is a translation of the much-used epithet patit-pavan ; see, for example, the closing chand of the Ramcaritmanas (7.130.9).

[12] The original verses are given by Grierson in "Notes on Tul'si Das," 267.

times cited as his "initiating teacher" (diksa[*]guru ). Other well-known stories concern the poet's ascetic and devotional practices (sadhana ) and his mystical experiences and miracles. Some of these will be recounted later in the words of modern devotees, for they show the reverence in which Tulsi and his poetry continue to be held.

The genesis of the Hindi epic of Ram has received considerable study.[13] Although the influence of Valmiki's classic may be taken for granted, Tulsidas makes significant departures from the older epic's version of the story, and some of these appear to reflect the influence of other Sanskrit texts. Thus the Bhagavatapurana[*] probably inspired his glowing depiction of Ram's childhood, while the drama Prasannaraghava may have influenced his decision to include a romantic encounter between Ram and Sita in a flower garden (phulvari )—a scene that has become one of the Hindi epic's most beloved passages (1.227.3-236). Another likely influence was the Adhyatmaramayana[*] ("spiritual" or "esoteric" Ramayana[*] ), a text probably composed in South India in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century, which added a significant dimension to the theology of Ram by presenting him as not only an incarnation of the preserver-god Vishnu but as the personification of the ultimate reality or ground of being—the brahman of the Upanishads and of the Advaita or non-dualist school of philosophy.[14] Although this interpretation weakened the narrative and reduced the character of Ram to an austere abstraction who could hardly arouse the devotional sentiments of the masses, it may have helped inspire Tulsi's more successful integration of the Advaita and Vaishnava systems. It also anticipated one of Tulsi's most striking deviations from the traditional story: his introduction of an "illusory Sita" who alone suffers the indignity of abduction and imprisonment in Ravan's stronghold, while the real Sita—Ram's inviolable sakti , or feminine energy—remains safely concealed in the element of fire.[15]

The Ramcaritmanas is both the longest and earliest of the poet's major works; its composition was apparently begun when Tulsidas was in his early forties. The opening section of the poem includes the following well-known passage:

[13] Gupta, Tulsidas ; Vaudeville, Etude sur les sources ; and Bulcke, Ramkathaaur Tulsidas ; an English summary of Bulcke's analysis of the stages of composition is contained in his essay, "Ramacaritamanasa and Its Relevance to Modern Age," 58-75.

[14] Whaling, The Rise of the Religious Significance of Rama , 111. The text is available in an English translation by Bali Nath, The AdhyatmaRamayana[*] .

[15] The relevant passages are 3.24.1-5 (in which Sita conceals herself and substitutes her pratibimb , or "shadow") and 6.108.14-109.14 (in which the shadow is destroyed and the real Sita restored).

Now reverently bowing my head to Shiva

I narrate the spotless saga of Ram's deeds.

In this year 1631 1 tell the tale,

laying my head at the Lord's feet.

On Tuesday, the ninth of the gentle month,

in the city of Avadh, these acts are revealed.

1.34.3-5

Tulsi thus assigns the commencement of his labor to the birthday of Ram in the year 1631 of the Vikram Era—i.e., A.D . 1574—in Ayodhya, Ram's own city. The weighty text must have occupied him for several years, and the fact that its fourth book opens with an invocation to Kashi (Banaras) is generally taken as an indication that the poet had by then shifted his residence to that city.

Even though the immediate reception accorded to Tulsi's epic cannot be historically documented, several passages in the poet's works suggest a concern to anticipate and respond to critics. The invocatory stanzas of the epic include an ironic obeisance to the "ranks of scoundrels" who delight in criticizing others and a reference to "poetic connoisseurs" who are likely to laugh at his efforts, for as he observes,

My speech is the vernacular, my mentality simple.

It's deserving of laughter—no fault in laughing!

My speech lacks every virtue

but one, known to all the world.

Reflecting on this, let those

of pure discrimination listen well.

For herein is the lofty name of Raghupati—

utterly pure, essence of Veda and Purana!

1.9.4, 1.9, 1.10.1

While Tulsi's denial of poetic skill (couched, of course, in verses of great ingenuity) may have been aimed at those who favored the highly contrived Sanskrit poetry still influential in his day, his assertion that his work contains the essence of the scriptures was more likely directed at critics within the Brahmanical elite. That the vernacular Ramayan was initially derided in these conservative quarters is suggested by the hagiographical tradition and by a few verses in Tulsi's later works.[16] Yet such a negative reaction in turn suggests that the work had found an

[16] Thus in Vinay patrika 8:3, the poet complains to Shiva that the god's "servants" in Banaras have been tormenting him. The Gautam candrika speaks of "conceited traditionalists" taking offense at Tulsi's devotional verses.

enthusiastic reception among other groups, which may have included the mercantile class and the lower orders of society, including religious mendicants.

How rapidly the influence of the Hindi epic spread, in the absence of printing and despite the fact of overwhelming illiteracy, may be gauged from the fact that Nabha Das in his Bhaktamal —a work probably composed toward the end of Tulsi's life—hailed the Banarasi poet as Valmiki himself, who had taken birth again to reissue his Ramayana[*] to the world.[17] Nabha is thought to have resided at Galta, a Vaishnava shrine in Rajasthan, roughly a thousand kilometers from Tulsi's home but an important halting place for itinerant sadhus. It is likely that such mendicants played a major role in the early dissemination of the epic and were among its first expounders.

The small number of extant seventeenth-century manuscripts and the much larger number of eighteenth-century ones reveal some interesting features. Perhaps as many as 10 percent are in Kaithi, the script of the Kayasth, or scribal, caste—a writing system favored in political and economic contexts.[18] A smaller but still significant number are in Persian script, and the second-oldest translation of the epic (1804) is into the Persian language. All of this suggests the text's popularity with the aristocracy and business classes. Its association with Brahmans and acceptance by them as a work of the highest religious authority appears to have come about only gradually. As recently as. 1887, F. S. Growse could observe that there were many pandits who "still affect to despise [Tulsi's] work as an unworthy concession to the illiterate masses."[19]

A popular legend highlights the tension that is thought to have surrounded the religious establishment's initial response to Tulsi's epic. The Brahmans of Banaras, censorious of Tulsi for having rendered a sacred story in the common tongue, decided to test the worth of the text by placing it at the bottom of a pile of Sanskrit scriptures in the sanctum of the Vishvanath Temple, which was then locked for the night. When the shrine was opened in the morning, the Hindi work was found to have risen to the top of the pile, and its cover bore the words satyam[*] , sivam[*] , sundaram[*] (truth, auspiciousness, beauty) inscribed by an un-

[17] Rupkala, SriBhaktamal , 756, chappay 129. On the dating of this text, see Gupta, "Priya Dasa," 64.

[18] This estimate was made by C. N. Singh, who examined a large number of early manuscripts while helping edit the Kashiraj Trust edition—the first Manas edition to utilize Kaithi manuscripts; interview, February 1984.

[19] Growse, The Ramayana[*]of Tulasidasa , lv.

known hand. Faced with this divine imprimatur (in Sanskrit, no less), the pandits were forced to give grudging respect to the text.[20]

The legend suggests Tulsi's success at transcending sectarian differences and at synthesizing diverse strands of the Hindu tradition. In the nineteenth century, Growse noted the abundance of sects identifying themselves with the names and teachings of their founders, and Tulsi's overarching and catholic influence: "There are Vallabhacharis and Radha-Vallabhis and Maluk Dasis and Pran Nathis, and so on, in interminable succession, but there are no Tulsi Dasis. Virtually, however, the whole of Vaishnava Hinduism has fallen under his sway; for the principles that he expounded have permeated every sect and explicitly or implicitly now form the nucleus of the popular faith as it prevails throughout the whole of the Bengal Presidency from Hardwar to Calcutta."[21]

Reconciliation and synthesis are indeed underlying themes of Tulsi's epic: the reconciliation of Vaishnavism and Shaivism through a henotheistic vision that advocates worshiping Shiva as Father of the Universe while making him the archetypal devotee of Ram. A similar rapprochement is effected between the nirgun[*] and sagun[*] traditions—between worship of a formless God and of a God "with attributes." Tulsi's contribution is to offer, in Frank Whaling's words, "an integral rather than a new symbol" of Ram,[22] and his hero is at once Valmiki's exemplary prince, the cosmic Vishnu of the Puranas, and the transcendent brahman of the Advaitins. What weaves together such "inconsistent" theological strands is the overwhelming devotional mood of the poem, expressing fervent love for the divine through poetry of the most captivating musicality.

The Ramcaritmanas is one of a dozen works generally accepted as authentic compositions of Tulsidas.[23] These include six "minor" and six "major" texts that together have acquired a sort of canonical status for the Ram tradition, so that their verses may be cited as authoritative "proof" or "validation" (praman[*] ) of any point an expounder or commentator wishes to make. In addition to these literary works, the North Indian oral tradition includes a sizable body of couplets and short songs that claim Tulsidas as their author by inserting his name in the poetic

[20] The legend is recounted in the Mulgosaim[*]carit ; the version given here is based on an oral retelling by a temple priest of Ramnagar; February 1984.

[21] Growse, The Ramayana[*]of Tulasidasa , lix.

[22] Whaling, The Rise of the Religious Significance of Rama , 228.

[23] For a short summary of their contents, see Grierson, "Notes on Tul'si Das," 197-205, 253-59.

"signature line" (bhanita ) common to such poems. Some of these aphorisms and songs are indeed drawn from Tulsi's written works—scores of lines from the Ramcaritmanas have entered folk speech as proverbs[24] —but others belong to none of the poet's known works or are in dialects (such as Khari Boli) or even other North Indian languages (e.g., Punjabi and Gujarati) that he is unlikely to have known.[25] Such fragments belong to a genre of literature in which folk poets assume the name and persona of famous poets—Kabir, Tulsi, Surdas, and Mira being four favorites—in order to invoke a characteristic ethos or aura of authority.[26] But whereas the proliferation of such compositions has sometimes confused or even obliterated the boundaries of a poet's authentic oeuvre,[27] the Tulsidas oral tradition exists as a complement to a distinct and well-attested literary corpus. Thus while editions of Surdas's major work, Sursagar , may contain anywhere from a few hundred to many thousand poems, the numerous published editions of the Ramcaritmanas exhibit only comparatively minor variations.[28]

One other poem needs mention in the context of Tulsi's works, genuine or otherwise. The Hanumancalisa —"forty verses to Hanuman"—which popular belief, backed up by a signature line, universally attributes to Tulsidas, has become one of the most recited short religious texts in contemporary North India.[29] The poem opens with a couplet from the Ramcaritmanas and contains several other lines that appear to be adapted from the epic; the remainder suggests a rather inelegant approximation of Tulsidas's style. But questions of authenticity and literary merit aside, the most striking thing about this poem is its enormous popularity. As a prime text of the flourishing cult of Hanuman—one of the most visible manifestations of popular Hinduism—it is fervently recited by millions of people every Tuesday and Saturday, the two week-

[24] Examples of these may be found in the section on lokokti (folk sayings) in Shukla, ed., Tulsigranthavali 4:93-158.

[25] Some of these compositions may be attributable to later authors who bore the same name, such as Tulsi Sahab of Hathras (1763-1843), a poet of the Sant tradition who is regarded by some devotees as a reincarnation of Tulsidas.

[26] Bhanita literally means "uttered"; such a poetic signature is also known as a chap , or "seal." On this convention, see Hawley, "Author and Authority," 269-90. On its use by Kabir and others, see Vaudeville, Kabir , 62.

[27] On the problem of delineating an "authentic" Surdas, see Bryant, Poems to the Child-God, vii-xi; and Hawley, SurDas , 35-63. Textual problems in Kabir are discussed by Vaudeville, Kabir , 49-70. No early manuscripts exist for the countless poems attributed to Mirabai; see Hawley and Juergensmeyer, Songs of the Saints of India, 122-29.

[28] For a discussion of variant manuscript readings, see Chaube, Manasanusilan , 37-169; or Mishra, ed., Ramcaritmanas , 463-501.

[29] For a rough translation accompanied by some discussion of the poem's message and popularity, see Kapoor, Hanuman Chalisa.

days regarded as especially suitable for worshiping Ram's ideal devotee, and also at other times when special assistance is sought (thus it is said that the onset of annual school examinations brings a flood of college students into Hanuman temples to devoutly' intone the prayer). Authentic or not, the verses of the Hanumancalisa are today among the best-known lines attributed to Tulsidas.[30]

Since the Ramcaritmanas is a text in the Ramayan tradition, for which the Sanskrit epic of Valmiki is the accepted archetype, it is commonly referred to simply as "the Ramayan" and many popular editions bear only this name on their spine and cover, perhaps adding above it in small print: "composed by Goswami Tulsidas" (GosvamiTulsidas-jikrt[*] ).[31] Such use of the generic title is of course revealing of the fact that this epic has become in effect the archetypal Ramayan text for Hindi speakers. The "Ramayan composed by Valmiki" (Valmikikrt[*]Ramayana[*] ) is to the vast majority of people only a famous name for the archetype of a beloved story, not a known or accessible text, and most Hindi versions of it are prose condensations of its story, not literal translations of its verses.[32] Few devotees would be able to describe how Tulsi's version differs from its Sanskrit precursor, for their conception of the story depends overwhelmingly on the Hindi poet's rendition of it. And indeed, the immensely successful Indian television serialization, "Ramayan," which aired during 1987-88, closely followed Tulsi's version of the story.[33]

The significance of Tulsi's own chosen title, Ramcaritmanas —which W. D. P. Hill has rendered "The Holy Lake of the Acts of Ram"—is discussed in some detail below. Although Western authors have sometimes replaced this unwieldy compound with the acronym RCM, the Hindi tradition prefers to shorten it to its final element and call it simply the Manas —a custom I follow here.[34] This abbreviation, as we shall see, is not a mere truncation of the title, but a significant condensation that focuses on the central metaphor of the poem.

[30] Despite his popularity, Hanuman remains little studied. To date, one of the best treatments is Wolcott, "Hanuman."

[31] The term gosvami ("master of cattle" / "master of the senses," commonly Anglicized as "Goswami") is a respectful title given to certain religious leaders; the suffix -ji connotes enhanced respect. In Vaishnava discourse, the term "Goswami-ji" normally refers to Tulsidas.

[32] A typical example is Gupta, Valmikramayan[*] .

[33] See Chapter 6, People of the Book.

[34] Even titles of scholarly works in Hindi often refer to the text by this name; e.g., Chaube, Manasanusilan (A study of the Manas ); Chaturvedi, ManaskiRam Katha (The Ram story in the Manas ). The same abbreviation occurs in speech, and a traditional scholar of the epic is sometimes termed a Manasi (Manas specialist).

Metrical and Narrative Structure

The Ramcaritmanas is a poem of roughly 12,800 lines divided into 1073 "stanzas" (to be defined shortly), which are set in seven "books" (kand[*] ). The latter division is common in texts of the Ramayan tradition and reflects the primacy and influence of the Valmiki epic, which is so organized. All but one of Tulsi's books bear the same names as those of the Sanskrit epic,[35] but this resemblance does not extend to their contents and relative lengths. Tulsi's first book, Balkand[*] , for example, is his longest, comprising roughly a third of the epic and including much introductory material not directly related to the Ram narrative; the Sanskrit epic's opening book is its second shortest and commences the story of Ram with relatively little digression.

Although by the standards of Indian epics the Manas is fairly compact (it is less than a third the length of Valmiki's version), it is nonetheless substantial, and the line-count noted above reflects a poem that in printed editions typically runs to between five and seven hundred pages. The titles and relative lengths of the seven books are as follows:[36]

Title of Book | Number of Stanzas |

1. Balkand[*] (Childhood) | 361 |

2. Ayodhyakand[*] (Ayodhya)[37] | 326 |

3. Aranya[*]kand[*] (The Forest) | 46 |

4. Kiskindha[*]kand[*] (Kishkindha) | 30 |

5. Sundar kand[*] (The Beautiful) | 60 |

6. Lanka[*]kand[*] (Lanka) | 121 |

7. Uttar kand[*] (The Epilogue) | 130 |

Viewed in terms of the relative lengths of its sections, the work presents a rough symmetry: the first two and last two books are longer (the last two are lengthier than the stanza count suggests, as their stanzas themselves are generally longer), and the middle three shorter. The

[35] The exception is the sixth book, to which Valmiki gives the title Yuddhakanda[*] , "The Book of War."

[36] In all citations, the kand[*] will be indicated by number: "1" for Balkand[*] "2" for Ayodhyakand[*] , etc.

[37] This book contains a controversial stanza that some commentators regard as an interpolation; the Kashiraj edition, for example (published by the maharaja of Banaras under the editorship of Vishvanath Prasad Mishra) assigns no number to the troubling stanza (although it includes it), yielding an Ayodhya of 325 stanzas.

shortest book, Kiskindha[*]kand[*] , which describes Ram's encounter with the monkeys who will be instrumental in recovering his abducted wife, serves as a turning point in the narrative. Much of the first and last books consists of extended "introduction" and "epilogue" to the core narrative, which begins about halfway through the first book and ends about a third of the way into the final book.

The term "stanza" reflects no equivalent term in Hindi but is a useful designation for the conventional divisions of the text, which are based on a repeated sequential use of two meters: caupai and doha .[38] The former refers to a two-line unit containing four equal parts. Its individual lines are each known as an ardhali (half) and comprise thirty-two "beats" or "instants" (matra ), the metrical units of most Hindi prosody, which are based on the perceived relative duration of long and short vowels. Each ardhali is divided in turn into two feet (pad ) of sixteen beats, separated by a caesura (indicated in writing by a vertical line called a viram , or "stop"; a double viram marks the end of a full line). A sample line from Balkand[*] is given below; vowels marked with a macron and diphthongs are regarded as long and carry the relative weight of two beats; the others are short.

akaracarilakha caurasi | jatijivajala thala nabha vasi ||

(There exist) 8,400,000 forms of life, born by four modes, dwelling in water, on earth, and in the atmosphere.

1.8.1

Although in theory a caupai should consist of two such lines, in practice the term refers to any single line in this meter, and a person asked to recite "a caupai " from the Manas will usually quote an ardhali such as the one given above. Moreover, many stanzas contain an uneven number of lines, indicating that Tulsidas himself did not feel constrained to place such verses in pairs. Most modern editions of the Manas number each line in caupai meter as an individual unit, and this convention will be followed here.

As the epic's predominant verse form, caupais[*] have been likened by the poet to the lotus leaves that crowd the surface of a lake. They are interspersed, however, with the blossoming lotuses of more "ornamental" meters. The most common of these is the doha and its variant form, the soratha[*] . A doha is a couplet, each line of which consists of two unequal parts, usually of thirteen and eleven beats respectively; in reci-

[38] For a general introduction to Hindi prosody, see Kellogg, A Grammar of the Hindi Language; caupai meter is discussed beginning on p. 578.

tation, the break between the two parts of each line can be discerned, but in notation it is not shown.

magavasinara narisuni | dhamakamataji dhai | |

dekhi sarupasaneha saba | mudita janama phalu pai || |

Hearing this, people who lived along the road

came running, leaving homes and work.

Delighted to behold the embodiments of love,

all obtained their births' reward.

2.221

A soratha[*] is a doha's mirror image: two lines each divided into eleven and thirteen-beat segments, with the rhyme falling at the end of the first segment rather than at the end of the line.

Sankara[*]ura ati chobhu | Satina janahimaramu soi | |

Tulasidarasana lobhu | mana daru[*]locana lalaci || |

Shiva's heart was greatly agitated

but Sati did not perceive his secret.

Tulsi says, he craved sight of the Lord;

his mind hesitated but his eyes were greedy.

1.48b

Throughout the epic, each series of caupais[*] —commonly eight or ten lines—is bracketed by one or more dohas or sorathas[*] . These couplets are numbered consecutively throughout each book, and it is the repeated structural unit of caupais[*] + doha/soratha[*] that I refer to as a "stanza." Thus, for example, the citation "7.24.6" refers to the sixth line in the twenty-fourth stanza of the seventh book (Uttar kand[*] )—the stanza that concludes with doha number 24.[39] When a stanza concludes with a series of couplets, it is the convention to assign them a single number and to designate individual couplets with letters of the alphabet. Thus "24c" refers to the third of a series of couplets at the end of stanza twenty-four.

The use of the caupai-doha stanza as the basic structural unit for a poetic narrative was not original to Tulsidas but appears to have had a long history in the North Indian vernaculars. In Avadhi itself—the dia-

[39] One could argue that a stanza might just as reasonably begin with a doha/soratha[*] , since all but one of the kands[*] open with invocatory verses in these meters. In fact, both notation systems are in use, but oral performers typically seem to regard the doha as a unit of closure, and the authoritative commentary Manaspiyus[*] (ed. Sharan) prefers this approach. As a consequence of this convention, invocatory dohas will be designated by a "zero" (0) in notation; thus "2.0" refers to the doha that opens Ayodhyakand[*] .

lect of the Manas —it had been used in a number of allegorical romances by Sufi poets, beginning with the Candayan of Maulana Daud (c. 1380) and including the great Padmavati of Malik Muhammad Jayasi (c. 1540).[40]

A third meter that occurs with fair frequency in the Manas is harigitikachand —"meter of short songs to Vishnu"; this is generally shortened to chand in notation. Verses in this meter seem to be inserted at moments of heightened emotion and serve to elaborate on something that has already been described rather than to advance the flow of the narrative, for which the more prosaic caupai is preferred. Chands are nearly always placed between a group of caupais[*] and their concluding couplet; thus they are contained within "stanzas" as defined above, and in my notation simply continue the numbering of stanza lines. A chand comprises four equal lines of twenty-six to thirty beats. The final syllables in each line rhyme and there is often internal rhyme within lines; the rhyme scheme, combined with the frequent use of alliteration, gives this meter an especially rhythmic and musical quality. Appropriately, it is the chands among all the verses of the Manas that are most often set to melodies and sung as devotional hymns.[41] A famous example occurs in the passage celebrating Ram's liberation of Ahalya—a woman transformed into a stone by her husband's curse. The first two lines of this chand read:

parasata pada pavanasoka nasavanapragata[*]bhaitapa punjasahi |

dekhata Raghunayakajana sukha dayakasanamukha hoi kara jori rahi ||

1.211.1,2

In his 1887 translation F. S. Growse attempted to simulate the rhyme scheme of some of these musical verses; for the above lines he offered:

At the touch so sweet of his hallowed feet,

she awoke from her long unrest,

and meekly adored her sovereign lord,

awaiting his high behest.[42]

Whatever the aesthetic merits of this approach, it necessitated taking considerable liberties with the text; a more literal translation would be:

[40] On the genre of Sufi premakhyan (allegorical romance) in Avadhi, see Millis, "Malik Muhammad Jayasi."

[41] For example, in one commercial recording of Manas hymns (SriRamayanamah[*] , Bombay: Polydor of India, Ltd., 1979), nearly all the selections are in chand meter.

[42] Growse, The Ramayana[*]of Tulasidasa , 133.

At the touch of his holy feet, which destroys grief,

that treasury of asceticism became manifest.

Beholding Ram, who delights his devotees,

she stood before him with palms joined.

Meters other than the caupai , doha/soratha[*] , and chand occur only rarely in the Manas . They include invocatory, Sanskrit slokas , which open each book and close the final one, and occasional hymns of praise (stuti ) spoken by characters—learned Brahmans or sages—who might be expected to address the Lord in Sanskrit; several of these are widely used in worship today.[43] Another Hindi meter called tomar chand (spear meter)—similar to the caupai but with shorter and more strident lines—occurs twice during battle scenes (3.20.1-13; 6.113.1-16), to which it was evidently thought to be well suited.

Apart from its division into books and stanzas, the Manas has, in the view of its audience, a further implicit division into episodes (prasang[*] ) and dialogues (samvad ). These appear to reflect the conventions and constraints of oral storytelling and sequential recitation.[44] Their acquired names are often printed in the margins of modern editions for the convenience of devotees and are commonly invoked in oral discourse on the epic—thus a traditional scholar may be asked to expound the "episode of the departure for the forest" (van-gaman prasang[*] ) or "Ram's dialogue with the boatman" (Ram-kevat[*]samvad ). Certain beloved passages have acquired names that seem to bear little relation to their narrative content; thus, Lakshman's philosophical discourse to the tribal chief Guha in Book Two[45] is commonly referred to as Laksman[*]gita (The Gita expounded by Lakshman)—implying the similarity of its message to that delivered by Krishna to Arjuna in the Mahabharata .

One other convention deserves note, for it is used frequently in all the recurring "ornamental" meters of the epic: the bhanita , or signature of the poet. This usually consists of the word "Tulsi" or "Tulsidas" placed in a line in such a way that it must be construed to mean "Tulsidas says . . ." or taken as an interjection ("O Tulsi!"). Although such a signature was a convention in medieval lyric poetry that added an element of personal witness to the verses, within the epic scope of the Manas it was adapted to serve an additional purpose: to remind the

[43] E.g., Atri's hymn to Ram (3.4.1-24); Sutikshna's hymn to Ram (3.11.3-16); a pious Brahman's hymn to Shiva (7.108.1-18).

[44] Weightman suggests that it is in part the episodic structure of the Manas that makes it "read" badly in translation and gives Western readers a poor impression of the effect of the original; "The Ramcaritmanas as a Religious Event," 60.

[45] 2.92.3-94.2.

audience of an overarching design within which the narrative is set. This design and its significance must now be briefly examined.

The Fathomless Lake: Tulsi's Narrative Framing

Recent studies in sociolinguistics and in the rhetorical approach to literary criticism have drawn attention to the technique of "framing"—the framing of communication in general and verbal art in particular. This concept has been developed and applied by linguists and anthropologists and most recently by folklorists interested in the study of "verbal art as performance"—to cite the title of an essay by Richard Bauman that makes a valuable contribution to performance theory. Drawing on the work of Gregory Bateson, Bauman notes,

It is characteristic of communicative interaction that it includes a range of explicit or implicit messages which carry instructions on how to interpret the other messages being communicated. This communication about communication Bateson termed metacommunication. . . . In Bateson's terms, "a frame is metacommunicative. Any message which either explicitly or implicitly defines a frame ipso facto gives the reader instructions or aids in his attempt to understand the messages included within the frame."[46]

The theme of the present study is the presentation of a literary work to its audience, and the metacommunicative strategies employed by oral performers to "frame" the Manas are discussed in due course. It is useful, however, to begin by examining the ways in which the text itself has been deliberately "framed" by its author—that is, placed within contexts that provide the listener/reader with clues for interpreting its message. Such framing, I suggest, is not simply a literary convention but a cue to the intended use of the text in cultural performances.

Two explicit frames are built into the structure of the Manas ; each has implicit dimensions that may not be readily apparent to readers of a different cultural background. The first is the title itself, which is introduced in the thirty-fifth stanza and then developed into a complex allegory comprising more than a hundred lines. I identify this frame as "first." because, in selecting this title, Tulsi knew it was likely to be the first message about the work that would reach a listener. Hill's English rendering, "The Holy Lake of the Acts of Ram," though unexceptionable, inevitably fails to convey the mythological associations that the title evokes for the North Indian listener.

[46] Bauman, Verbal Art as Performance, 15. Bauman cites Bateson's Steps to an Ecology of Mind (New York: Ballantine, 1972), 188.

The name Ram , no doubt the poet's own dearest element in the title—his mantra, or spiritually efficacious word par excellence—needs little elaboration here; not merely the name of the hero of the narrative, it was to Tulsi and his fellow devotees the personal designation of the supreme godhead.

I venerate "Ram," the name of Raghubar,

the cause of fire, sun, and moon.

Breath of the Veda, filled with Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva,

incomparable, qualityless; treasury of all qualifies.

The Great Mantra that Shiva repeats

and his instruction, giving liberation in Kashi.[47] 1.19.1-3

The Sanskrit word carita (from the verbal root car, "to move") is a perfect participle connoting "going, moving, course as of heavenly bodies," and by extension, "acts, deeds, adventures."[48] The compound Ram-carit is thus roughly synonymous with the term Ramayana[*] , if the latter is taken to mean "the goings [movements] of Ram" (Rama + ayana ). Yet carit is not random movement but expresses the inherent qualities of the mover; in Sanskrit literature the word has been used in the titles of biographies of religious figures and idealized kings (e.g., the Buddhacarita of Asvaghosa; the Harsacarita[*] of Bana). A Manas scholar in Banaras once expressed the meaning of carit with an analogy to geometry: a car is a moving point and its carit the circle it inscribes—the track or orbit that records its passage. In this interpretation, Ram is the moving point of the infinite that passes through our world, the track of his passage being delineated by his carit. For Tulsidas, this was an appropriate term to describe the earthly activities of one whom he revered as the incarnation of God.

Manas is derived from the root man —"to think, believe, imagine, perceive, comprehend."[49] This root and its derivatives—such as the Sanskrit word manas —pose a perennial problem for the translator, in that no one English term can express both its cognitive and its emotional connotations: it is frequently rendered as either "mind" or "heart." From this term is derived the word manas —"arising out of manas, "

[47] Mahatma Gandhi's reputed dying exclamation, "He Ram!" (O Ram!) offered a dramatic example of the widespread habit of invoking the name in moments of crisis. Tulsi helped popularize the belief that it is by virtue of the power of Ram's name, which Shiva whispers in the ear of anyone who dies in Kashi (Banaras), that liberation from further rebirth is assured.

[48] Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, 389.

[49] Ibid., 783.

"belonging to manas "—that is, mind/heart-born. Used as a proper noun, this is the name of a remote Himalayan lake, situated on the Tibetan plateau at the foot of Mount Kailash, the abode of Shiva. References to this lake are found in numerous texts, beginning with the Mahabharata and Ramayana[*] epics.[50] In later religious poetry, the lake is often used as a metaphor for the mind itself in its highest aspect: its waters are said to be as pure and still as the consciousness of the contemplative is to become, and on their surface floats the stainless hamsa[*] bird—symbol of the Self—which feeds on the pearls it plucks from the lake's clear waters. The discriminating hamsa[*] also possesses the ability to separate milk from water, a skill that Tulsi likens to the ability of saintly people to grasp the good and discard the evil in worldly life (1.6).

The Manas , then, is the "Holy Lake" of Hill's translation: a profound reservoir gleaming at the foot of towering white peaks.[51] This, the poet identifies as the fountainhead of Ram's mysterious carit, from which the discriminating listener, hamsa -like[*] , may extract clues to Ram's reality. Tulsi attibutes the origin of the narrative and its title to Shiva himself.

Shiva formed this and placed it in his heart.[52] Finding good occasion he narrated it to Parvati.

Upon contemplation, the excellent name,

Ramcaritmanas , he joyfully gave it.

1.35.11,12

He then begins his allegory, first situating the mystical lake in the "soil of good intelligence" in the depths of the heart, and the source of its water in the boundless ocean of scripture—the revealed Vedas and the Puranic "old stories" (1.36.3). The saints are likened to clouds? which draw this water from the depths and release it in showers of "Ram's fame"—the stories of his deeds, which enter the heart through the channels of the ears and so fill the Manas reservoir.

Having established the origin of his lake, the poet describes its surroundings:

[50] For relevant references, see Mani, Puranic Encyclopaedia, 474. The Valmiki text states that the river Sarayu, which flows through Ayodhya, arises from this lake (1.23.7,8 in the Critical Edition)—an idea that is developed in Tulsi's allegory. See Bhatt and Shah, eds., The ValmikiRamayana[*] .

[51] Hagiographic tradition maintains that Tulsi's wanderings included a visit to this remote and sacred goal of Hindu pilgrims. For a modern account of the pilgrimage, see Hamsa, The Holy Mountain.

[52] There is a play on words here, as the term I have rendered "heart" is actually manas .

The four lovely and excellent dialogues,

shaped by lucid contemplation,

are the four charming ghats

of this holy and auspicious lake.

1.36

The word "dialogues" (samvad ) refers to the other explicit set of frames, which will be discussed shortly: the narrating of the Manas as a series of interwoven conversations; these form the banks of this lake of Ram's glory. The poem's seven books are called "stairways" or "descents" (sopan ), leading down the ghats into the water, while its meters are the lotus leaves and flowers that cover the water's surface (1.37.1,4,5). Living creatures are added to the picture—the "bees of good deeds," which sip the nectar of the lotus verses; the "swans" of wisdom and detachment, and the "fish" of various poetic devices and moods, which dart about below the water's surface (1.37.7,8). Surrounding the lake is a forest of mango trees—"the assembly of devotees"—and the faith of these good people is the spring season, which ever reigns there (1.37.12). Thus the poet introduces into his landscape the potential audience of his poem.

Those who diligently sing these acts

are the skilled guardians of this lake.

Men and women, ever listening with reverence,

are the fortunate gods, masters of this Manas .

1.38.1,2

Similarly, lustful and vindictive people are said to be like crows and storks (the former impure, the latter scheming, according to the Hindu bestiary), but the lake holds no attraction for them, as it is free of the "snails, frogs, and scum" of sensual stories (1.38.3,4). Should they ever get a glimpse of it—which is all but impossible, since access is blocked by "straying paths of bad company" and "towering peaks of domestic cares" (1.38.7,8)—they will go away disappointed, without having drunk or bathed in its waters, and will afterward abuse it to others and discourage them from setting out to find it. Yet,

All these obstacles cannot obstruct one

on whom Ram has looked with grace.

Such a one bathes reverently in the lake

and the three terrible fires cannot scorch him.

Brother, let him who yearns to bathe in this lake

diligently cultivate the company of the holy!

1.39.5,6,8

The poet then describes how .the "gladdening current of love" arises from the lake to become the "river of lovely song," which he identifies with the Sarayu, the sacred stream of Ayodhya. Later it joins the "Ganga of devotion to Ram" and the mighty Son, signifying "the fame of Ram and his brother in battle," until the many merged streams flow into "the ocean of Ram's inherent being" (1.40.1-4). Succeeding stanzas further expand the allegory, likening the major episodes of the narrative to various features of the river and its banks, and to the appearance of the river in each of the six seasons of the North Indian year (1.42.1-6).

The imagery of the Manas Lake and its ghats is not confined to this introductory passage but is reaffirmed periodically throughout the poem. Each of the seven books, true to the allegory, is termed a "descent" into the lake (sopan ). Balkand[*] is the "first descent," Ayodhya is the second, and so on, each stage in the narrative drawing the listener deeper into the waters. In the final book, the image of the lake is reintroduced in the dialogue between Bhushundi and Garuda, which serves as an epilogue to the narrative.[53]

The appropriateness of Tulsidas's choice of the Manas Lake as an allegorical frame for his epic is best appreciated in light of the role that the text has come to play in North Indian society—as a great reservoir of myth, folk wisdom, and devotional expression on which people constantly draw. The image also suggests a source of meaning that can never be exhausted, a story that can be continually reinterpreted and expanded on; this concept, as will be seen, is a presupposition of all Manas performance, as is the notion that there can never be a single definitive interpretation of the text.

The second explicit framing device in the Manas —the presentation of the narrative through a series of four dialogues—exemplifies a traditional pattern in Indian literature: the presentation of a text as an oral narration by a particular teller to a particular listener, within a carefully delineated context. Although hardly unique to India, this device has been used there with very striking consistency, even outside the realm of "story" literature; indeed many premodern philosophical, aesthetic, and scientific treatises were framed as contextualized dialogues. Even though it is not possible here to explore all the ramifications of the use of this kind of framing in Indian literature, a few relevant points may be raised. First and most obviously, the technique suggests an intimate and unbroken connection between oral and written literature, and a contin-

[53] See, for example, 7.92, which speaks of the "fathomless reservoir of Ram's qualities," and 7.113.9, where the theme of the title and its significance is again taken up.

uing awareness of the former as a source and model for the latter. A second point involves the problematic but utilitarian notion of India as a "traditional" society—as contrasted to the equally problematic category "modern." A traditional society is generally held to be one in which norms of behavior established or thought to have been established in the legendary past are accepted as authoritative and frequently invoked in reference to present behavior, and in which "originality" that involves a radical departure from these norms is discouraged (although originality in the reassertion or even the reinterpretation of norms may be highly prized). In such a society, as Bauman has observed, an "appeal to tradition," often accompanied by a "disclaimer of originality" (at least as regards the content to be communicated) can serve as one of the most important "keys" to performance—a necessary cue to prepare listeners/readers to become an audience for a display of verbal art.[54]

A perhaps more useful designation for India is as a "context-sensitive" society, in which people perceive much of their behavior against a background of social, religious, and historicolegendary contexts.[55] Performances in such a society must be "keyed" by reference to traditional frames, because frames provide the contextual information necessary for the reception of a communication as a performance and thus become constitutive of the very nature of verbal art.

Like the society for which it was created, the Manas too is "context-sensitive," and one of its relevant contexts is the tradition of oral retelling of the Ram legend—a story that people invariably hear long before they ever (if ever) read it. Early in the first book, the poet tells how he came to hear it.

I too heard from my guru

that story, in Sukarkhet.

But I didn't comprehend it,

being but an ignorant child.

Teller and listener should be treasuries of wisdom;

Ram's tale is mysterious.

How could I, ignorant soul, understand,

a fool in the clutches of the Dark Age?

But then the guru told it again and again,

and I grasped a little, according to my wit.

That very tale I set in common speech,

that it may enlighten my heart.

1.30a,b; 1.31.1,2

[54] Bauman, Verbal Art as Performance, 21.

[55] This concept was first brought to my attention by A. K. Ramanujan; personal communication, February 1979.

Tulsidas's "appeal to tradition" and "disclaimer of originality" goes beyond this bit of autobiographical detail, however, for his retelling of the legend of Ram is set within the context of no less than four narratives—the "four excellent dialogues" mentioned earlier. They are introduced in a passage immediately preceding the lines just cited (which themselves identify the fourth teller/listener pair: Tulsidas himself and his audience):

Shiva formed this beautiful story

and then graciously related it to Parvati.

The same he gave to Kak Bhushundi,

recognizing him as Ram's devotee, and worthy of it.

From him then Yajnavalkya obtained it

and he recited it to Bharadvaj.

1.30.3-5

The four frames thus implied may be diagramed as in Figure 2.[56]

Such narrative genealogies are common in Hindu literature, and a large number of medieval religious texts, especially those of the tantric tradition, ultimately trace their teachings to dialogues between Shiva and Parvati. Tulsi was thus appealing to a well-established tradition in his choice of Shiva as the primal narrator; he was also buttressing one of his prime theological positions—the fundamental compatibility of Vaishnavism and Shaivism—by depicting Shiva as a model devotee of Ram. But Tulsi's sequence of narrative frames is not merely a textual genealogy, cited at the start of the work and not referred to thereafter; all four narrators remain actively present throughout, and at any given moment one of them is always speaking, addressing his respective listener. Even in straightforward narrative passages, the poet interjects frequent asides from speaker to listener, including a vocative identifying the latter (such as "O Best of Birds!"—an epithet of Garuda—or "O Uma!"—another name for Parvati) and hence, by extension, the narrator as well. The transition from story to frame and back again is often abrupt and may strike the Western reader as a gratuitous interruption of the tale. Yet the device occurs with such frequency that one must assume it to be an important element in the poet's strategy; evidently Tulsi expected his audience to remain continuously aware of all four narrative

[56] The diagram postulates a "chronological" transmission, but in fact the exact sequence is a matter of debate. The ambiguity in my translation reflects that of the original: does "him" in the third verse refer to Shiva or to Bhushundi? Other passages confuse the issue further—at one point Shiva is described as hearing the story from Bhushundi (7.57), who in turn is said to have learned it from the sage Lomash (7.113.9,10); the unraveling of such enigmas is among the special tasks of traditional expounders. All commentators agree, however, that Shiva's narrative is the archetype, and Tulsi's its most removed descendant.

Figure 2.

Narrative framing in the Manas

frames. A good example is the passage in Sundar kand[*] (5.41.6-8) describing Ravan's abuse of his brother Vibhishan, who has advised him to return Sita to Ram:

(narrative: Ravan kicks Vibhishan) | Thus saying, he struck him with his feet. |

(aside: Shiva to Parvati) | O Uma! Such is the greatness of saints, who always return good for ill. |

(back to narrative: Vibhishan speaks) | Well may you, who are like a father to me, abuse me. Yet Lord, your salvation lies in worshiping Ram![57] |

It seems appropriate that the frame diagram presented earlier should resemble a telescoping box-lens, or a pool set below a series of descending steps. These metaphorical images suggest the poet's strategy in periodically shifting his focus: now placing listeners in the midst of the story, now withdrawing them to a desired distance in order to call their

[57] See also 1.124a,b, in which a single doha/soratha[*] pair includes comments from Shiva, Yajnavalkya, and Tulsi.

attention to contextual material in light of which he desires them to. interpret it; of alternately immersing them in the depths of his lake and lifting them back to its peripheral ghats. Tulsi thus weaves a series of "commentaries" into the very fabric of his text.

Another frame is implied as well: just as Tulsi is relating the story and commenting on it to his listeners, so they in turn may become tellers of and commentators on his story through the performance genres that have developed around its recitation. It is worth noting here that the tradition of oral and written commentary on the Manas discussed in chapters 3 and 4 came to regard the four dialogues precisely as contexts or "approaches" (as a ghat is an approach to a body of water) according to which the Ram story might be interpreted. The diagram favored by most commentators disregards the chronological element of story transmission and assigns to each dialogue and ghat a cardinal direction, setting them equidistant from the lake/narrative, as shown in Figure 3.[58]

A brief account of the interrelationship between the epic's narrative frames will serve both to suggest how the poet uses them to emphasize various aspects of the story, and to acquaint the reader with some of the distinctive features of Tulsi's retelling. The opening of Book One places the listener at the outer rim of the first diagram; speaking in his own voice, Tulsidas invokes the blessings of all beings in the mighty labor he is about to undertake and presents his allegory of the mystical lake. Stanza 43 concludes this introduction and begins the account of the meeting between the sages Yajnavalkya and Bharadvaj in the latter's hermitage at Prayag. Bharadvaj presses Yajnavalkya to tell him the story of Ram, feigning confusion over the question of whether the legendary prince of Ayodhya could be the same transcendent Ram whose name "the immortal Shiva eternally repeats" (1.46.3). Here Tulsi introduces one of his major themes: the reconciliation of the nirgun[*] (quality-less) and sagun[*] (endowed with qualities) conceptions of divinity. Yajnavalkya relates how a similar confusion once arose in the mind of Shiva's wife, Parvati, in her former incarnation as Sati. This leads to a lengthy retelling of the Puranic story of Sati's suicide at King Daksha's sacrifice; her rebirth as Parvati, daughter of Himalaya; and eventual reunion and marriage with Shiva (1.47-1.103). Tulsi's exuberant retelling of this popular myth runs to nearly six hundred lines—about one-seventh of Balkand[*] .[59]

[58] The diagram is adapted from one given by Sharan in Manas piyus[*] . 1:583. I have heard similar diagrams "drawn" by oral expounders.

[59] Tulsi makes one of the motivating factors in Sati's suicide Shiva's renunciation of conjugal relations, due to her having once taken the form of Sita in order to test Ram's omniscience and having thus become in effect his own "mother" (1.54.1-1.64.8).

Figure 3.

The four ghats

With the conclusion of this tale, Yajnavalkya recounts a dialogue between the reunited Shiva and ' in which the god accedes to his wife's request that he relate the entire story of Ram. Shiva thus takes over as narrator from stanza 112 onward, bringing the listener to the innermost frame of the diagram. Yet he too does not begin the story at once but instead sets the stage for Ram's advent with a series of Puranicstyle tales involving curses and boons—the plot devices par excellence of traditional Indian fiction—that will precipitate the births of the principal characters.[60] It is only with the conclusion of the lengthy tale of King Pratapbhanu (some 240 lines) and at a point nearly midway through the first book that Shiva's actual narration of the Ram story begins—with the birth of the demon Ravan, his austerities and attainment of sovereignty over the world, and the gods' plea to Vishnu that he

[60] The stories of Jay and Vijay (1.122.4-123.2); Kashyap and Aditi (1.123.3,4); Jalandhar and Vrinda (1.123.5-124.3); Narad's intoxication (1.124.5-139); Svayambhu Manu and Shatrupa (1.142.1-152); and King Pratapbhanu (1.153.1-176).

take human form to destroy their enemy. Following the birth of Ram in stanza 191, the traditional narrative proceeds without major digression through the six succeeding books, concluding with Ram's triumphant return to Ayodhya and a glowing description of his idyllic reign.[61]

The central narrative concludes in stanza 51 of Uttar kand[*] , but the Manas continues for another eleven hundred lines. This lengthy epilogue focuses for the first time on the second narrative frame: the dialogue between the crow Kak Bhushundi and the divine eagle Garuda (Vishnu's symbolic vehicle), the special theme of which is the saving power of bhakti in the Dark Age. Like each of the earlier dialogues, it begins with a query. Garuda is confused by his master's apparent helplessness when in the human form of Ram. To enlighten him, Shiva sends him to meet one of the most unusual characters in the epic—an immortal being in lowly form (for the crow is said to be the "untouchable among birds"), who endlessly narrates the story of Ram to an audience of fowl on the summit of the mysterious Blue Mountain (nilparvat ) and reveals to Garuda the salvific power of Ram's name.[62]

The epic's concluding passages withdraw through the narrative frames to return listeners to the starting point. With the close of the Bhushundi-Garuda dialogue, Shiva delivers a final paean of praise to the story, ending with the famous dhanya (blessed, fortunate) passage, a ringing affirmation of the epic's values.

Blessed is the land where flows the Ganga,

blessed the woman faithful to her lord,

blessed the king who clings to proper conduct,

blessed the twice-born who strays not from his code,

blessed is wealth given in charity,

blessed intelligence grounded in virtue,

blessed the hour of companionship with the holy,

blessed a life of service to the twice-born.

O Uma, blessed and holy is that family,

revered in all the world,

in which is born a humble man

firmly devoted to Raghubir.

7.127.5-9, 7.127

[61] Tulsi chooses to omit the "tragic" episodes of Valmiki's Uttarakanda[*] —the second banishment of Sita, the exile of Lakshman, and Ram's ultimate death. These are well known m his audience, however, and an eighth kand[*] incorporating them is often appended to bazaar editions.

[62] Bhushundi (a.k.a. Bhushunda) was already known to the author of the c. twelfth-century Yoga vasistha[*] ; see Venkatesananda, The Concise Yoga Vasistha[*] , 276-87. Tulsi's introduction of this narrator, however, probably owes more to a postulated Sanskrit Bhusundi[*]ramayana[*] , a text of which has recently been published; see Singh, ed., Bhusundi[*]ramayana[*] ; for a grief discussion of this text, see Singh, "Bhusundi[*] Ramayana[*] and Its Influence on the Medieval Ramayana[*] Literature."

Parvati adds her own hymn of gratitude, whereupon—as in the beginning of the epic—Tulsi assumes his own voice to conclude.

By Ram's grace and according to my intelligence

I have sung this holy and beautiful story.

In this Dark Age there is no other expedient,

neither yoga nor sacrifice, formula, austerity nor ritual,

but to remember Ram, to sing "Ram,"

and to listen constantly to Ram's noble acts!

7.130.5-7

The Manas and the Western Audience