Three

The Text Expounded: The Development of Manas-Katha

Infinite is the Lord, endless his story,

told and heard, in diverse ways, by all good people.

1.140.5

![]()

The Telling and Its Milieu

The preceding chapter discussed the dissemination, beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century, of printed editions of the Manas , and the related phenomenon of the rise of ritualized public recitation. Yet even today, when inexpensive printed editions are readily available, the major part of the epic's vast and devoted constituency does not gain exposure to the text primarily through reading or even through recitation. Adult male literacy in Uttar Pradesh state, the heartland of the Hindi-speaking region, remains less than 40 percent; female literacy, less than 15 percent. At the beginning of this century the percentages were far lower, and we may conclude that in earlier times literacy was confined to a very small minority of the region's population.[1]

Ritualized recitation may be widespread today, at least in urban areas, but it appears to be more an effect than a cause of the epic's popularity; moreover, it is usually executed in too cursory a fashion to impart much knowledge of the text to listeners not already familiar with

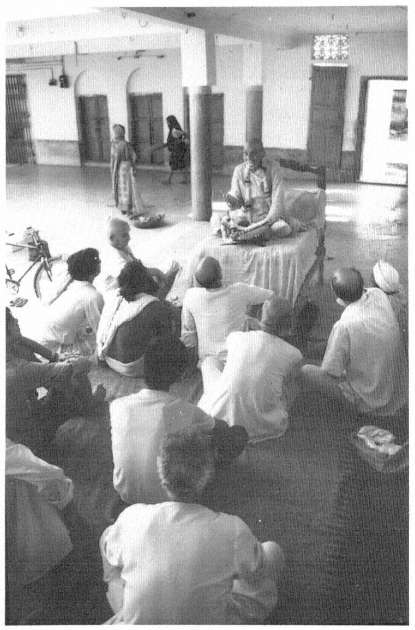

Figure 14.

Baba Narayankant Tripathi discoursing to the faithful at Sankat

Mochan Temple, 1983

it. Such rituals celebrate the sanctity of the Manas and capitalize on its fame, but we must look elsewhere for an explanation of how the vast majority of devotees, urban and rural, literate and illiterate, have for the past four centuries come to know and love the epic. They must, of course, have learned it through "recitation," but recitation of a different kind than any we have thus far examined: slow, systematic, storytelling recitation, interspersed with prose explanations, elaborations, and homely illustrations of spiritual points. This kind of systematic recitation-with-exposition is known as Katha .

Although the noun Katha is often understood to mean simply "story," this English translation tends to overly nominalize a word that retains a strong sense of its verb root. In India a story is, first and foremost, something that is told , and the Sanskrit root kath , from which the noun is derived, means "to converse with, tell, relate, narrate, speak about, explain." Katha might thus be better translated as "telling" or narration; Monier-Williams gives the most archaic meaning of Katha as "conversation . . . talking together,"[2] and as we shall see, a dialogical milieu is fundamental to Katha performance. To tell a story implies that there must be someone to hear it, and in Hindu performance traditions the role of the hearer (srota ) is participatory rather than passive.

The term Katha has a specialized, derivative meaning as well. When someone announces, "I am going to listen to Katha ," he refers to the telling of not just any story, but of a moral or religious one, generally by a professional storyteller and within the context of a devotional gathering. Katha is associated particularly with Vaishnava bhakti —with the cult of the deity who, in his various earthly incarnations, is the archetypal actor in our midst and the hero of endless narrative. Since at least the time of the composition of the Puranas, the hearing of Katha has been regarded by bhakti teachers as one of the most efficacious ways to cultivate a love for Bhagvan and to learn of his sportive acts—his lilas . Although a Katha performance might in theory be based on any of the epic or Puranic texts and one can find examples of contemporary performances utilizing such texts as the Mahabharata , the Valmiki Ramayana[*] , and the Padma purana[*] , at present only two texts continue to be widely performed in Katha style in Hindi-speaking areas: the Bhagavatapurana[*] and the Manas . The older Sanskrit text may have provided the model for the exposition of the Hindi epic, as it seems to

have done for its ritualized recitation, but its performance tradition appears to be in decline, while that of the Manas continues to flourish.[3]

There is another area of contemporary religious practice in which the term Katha is commonly used, seemingly in a very different context. A vrat Katha is a story connected with a vrat , or disciplined observance, generally involving a full or partial fast kept in fulfillment of a vow. Such fasts are commonly observed on specific days of the week (such as the Friday vrat in honor of Santoshi Ma, which has become popular with women in recent years, or the Satya Narayan vrat observed on Thursdays), or of the Hindu religious month (such as the Vaishnava ekadasivrat on the eleventh of a lunar fortnight); they involve, along with abstemious practices, the recitation of a relevant vrat Katha . These stories, together with instructions for the fast and its accompanying rituals, are contained in booklets widely sold in religious bookstalls.[4] Yet in this context too the term Katha does not. refer primarily to a text or even to a story but rather to an interactive performance. Instructions for a vrat usually require that its Katha be recited to someone, and only when the story has been "told" can the requirements of the vrat be considered to have been fully met.[5]

Katha is virtually a pan-Indian term, as the act of religious storytelling is a pan-Indian phenomenon, but the specific performance genres to which it refers vary from region to region. In Maharashtra and Karnataka there is the tradition of harikatha , in which a performer known as a kathakar narrates religious and didactic stories, often to musical accompaniment and with interludes of congregational singing.[6] In Telugu-speaking regions one finds the tradition of burrakatha , and audiences in Tamil Nadu patronize kathakalaksepam[*] (passing time through story) and a related folk genre known as piracankam[*] (from the Sanskrit prasangam[*] , or "episode"). For the Hindi-speaking region, Norvin Hein has documented the nearly lost kathak tradition of singing and storytelling accompanied by stylized gestures.[7] All of these genres have arisen

out of the Vaishnava narrative tradition and share similar conceptions of the religious efficacy of storytelling and of the importance of the devotional assembly. Further documentation of these styles must await the research of scholars knowledgeable in the various regional languages; my concern here is with the performance art of Katha as currently practiced in Hindi-speaking areas.

The term Katha and the performance tradition it reflects is of special relevance to the Manas text. For although Tulsidas sometimes uses a term that may be translated "book" (granth ), speaks of "good books" (sadgranth ), and mentions Puranas, sastras , and other classes of revered texts, he never refers to his own work as a "book"; the Manas itself is always styled a Katha . Moreover, like any Katha it has, at every point in its long narration, a teller (vakta ) and a listener (srota ), and—quite in keeping with the ancient sense of Katha as "conversation"—the narration unfolds in the course of a dialogue (samvad ) between these two. Thus the Katha narrated by Yajnavalkya to Bharadvaj is transmitted to us by Tulsi in the form of a samvad between the two sages.

The beautiful Katha that Yajnavalkya

told to the great sage Bharadvaj—

that very samvad will I relate.

Let all good people listen with delight.

1.30.1,2

Likewise, in the stanza that recounts the chain of transmission of the Manas-katha , Tulsi emphasizes the importance of the roles of both speaker and hearer and describes how he himself first heard the story from his guru.[8]

From such passages and numerous others of a similar nature (Tulsi uses the word Katha some 180 times in the course of the epic, very often in reference to his own narrative)[9] it is clear that Tulsidas conceived of the Manas as a Katha —that is, as a "telling" of the story of Ram with emphasis on the active, performative sense of this term. Further, in numerous phalsruti verses he encouraged his own listeners to become future tellers of the Katha and to "sing" it to others, thus continuing the chain of transmission.

He wins his heart's desire and all spiritual powers

who, abandoning hypocrisy, sings this Katha .

He who tells it, listens to it, and praises it

crosses the sea of illusion as if it were a cow's hoofprint.

7.129.5,6

Yet the poet also implies that his Katha may not be readily understood by all who hear it, as he himself did not grasp it at first hearing. Ram's Katha , Tulsi says, is gurh[*] : mysterious, profound, enigmatic. The listener must be a "treasury of wisdom" in order to grasp and explain its deeper meaning (1.30b). This is emphasized again in the allegory of the Manas Lake.

Those who heedfully sing these acts

are the skilled guardians of this lake.

1.38.1

Those who sing, Tulsi says, sambharkar —carefully, heedfully, with understanding—are to be understood as "guardians" of the Katha . The notions both of singing the poem "with understanding" and of guarding it (i.e., protecting it from incorrect readings and interpolations) have, as we shall see, acquired special significance for the Manas exegetical tradition.

Just as a Katha must always have a speaker and a listener, so must it have a milieu or environment; or rather, the environment is itself constitutive of the act of Katha . That environment is satsang[*] , "association with the good," a term that in the Vaishnava context refers specifically to attendance at devotional assemblies and participation in their activities: bhajan, kirtan , and Katha . Such assemblies of sants (good or saintly people; i.e., devotees of Vishnu) are the milieu in which Katha arises. In a verse in Balkand[*] , Tulsi likens the fellowship of virtuous people to the milky ocean, out. of the "churning" of which arises Katha in the form of the goddess Lakshmi, beloved of Vishnu (1.31.10). In a couplet in the final book, however, he is even more explicit about the relationship of satsang[*]to Katha and of Katha to the devotee's goal:

Without satsang[*] there is no Hari-katha

and without that, delusion will not flee.

Without delusion's flight, there can arise

no firm love for Ram's feet.

7.61

The relationship of satsang[*] and Katha , and of both to the promulgation of the Manas , was often brought home to me in conversations with devotees. Once on a long train ride, a young man noticed me reading the Manas and at once began to hum the famous refrain "Mangala bhavana

amangala[*] hari. . . ." Soon we struck up a conversation, which became (as conversations with Manas devotees often did) a kind of impromptu Katha , with the young man speaking enthusiastically about the epic and quoting verses to support his points while fellow passengers crowded around and added their own comments and approbation. The speaker, as it happened, was like myself engaged in writing a dissertation on the epic and was an avid devotee of daily recitation (five stanzas each morning, preceded by the gayatrimantra and the Hanumancalisa ). But when I remarked on how well he seemed to have learned the text and how much of it he had memorized, his response was revealing. Real knowledge of the Manas and learning its verses by heart, he told me, does not come from recitation, but from satsang[*] . "You sit down and listen, and then it really comes to you. That's how you memorize it: by listening." So great was his passion for Katha , he added, that whenever he heard of a program by a famous expounder he would "drop everything" and rush off to attend it.[10]

If even a literate, scholarly devotee can affirm that his knowledge of the Manas comes from hearing it expounded rather than from reading it, what of the illiterate ones who still make up the greater part of the epic's audience? At a village in Madhya Pradesh, near the pilgrim town of Chitrakut, I talked with an elderly farmer. Our talk was initially of water, for lack of which his village was suffering greatly, but when the subject of the Ramayan came up, his face brightened: Hanuman, of course, had been on this very spot; Ram's feet had walked the surrounding hills; the whole area was powerful and holy—and each point that the old man made was supported by a caupai or doha from the Manas . As I listened to this performance with growing admiration, I asked the old farmer how he came to know so much of the Manas . Had he ever read it? He smiled and gestured self-deprecatingly; clearly, the reading of books was not among his skills. Then he added proudly, "It is by the grace of satsang[*] that I know all this, only by satsang[*] ."

Epic and Puranic Exegetical Traditions

The composition of the Manas-katha in a poetic dialect based on one of the spoken dialects of the time was itself an act of mediation between the Ram devotees of Tulsi's day and such revered Sanskrit sources as the Valmiki epic and the Adhyatmaramayana[*] . Yet we should not presume that this written Katha , even at the time of its composition, was intended to stand by itself without further mediation or that its early "telling"

consisted only of reciting its text. The poem itself offers evidence to counter this assumption. As we have seen, it describes itself as "mysterious" or "enigmatic" and implies that not every hearer can fathom its deeper meaning. Although its language is not especially difficult, neither is it transparent; as poetry, it departs from spoken language not merely in the irregularities of its word order but also in its great compression, reflected in the frequent elision of pronouns, prepositions, and even verbs. One result is that many verses can be understood in a variety of ways, a feature that in itself invites comment and interpretation.

Moreover, like many retellings of the Ram legend, Tulsi's Katha assumes the audience's awareness of other versions of the story, especially the Sanskrit epic of Valmiki, and chooses to omit or merely allude to many incidents presented in detail in the earlier text. Often the allusions are so cursory as to be fairly opaque without some accompanying explanation. For example, in the poet's opening obeisance to Ayodhya, there is a line suggesting Ram's great love for the city and its people:

He purged the manifold sins of Sita's slanderers

and freeing them of remorse, established them in his world.

1.16.3

No further explanation is offered—the next line praises Kaushalya, Ram's mother—and the epic makes no other allusion to this theme. The first reference is, however, to the imputation of infidelity to Sita by certain men of Ayodhya, resulting in Ram's ultimate banishment of his innocent wife, and the second is to the final departure from earth of Ram and all his subjects. These incidents are described in Valmiki's Uttara kanda[*] ;[11] as already noted, the Manas prefers to end its central narrative with a description of the joys of Ram's earthly rule.

Similarly, when Ram, Lakshman, and Vishvamitra, en route to Videha, reach the shores of the Ganga, the poet makes another one-line reference—this time to a famous myth that occupies fully ten chapters of Valmiki's first book:[12]

Gadhi's son [Vishvamitra] related the whole story

of how the divine river came to earth.

1.212.2

Sometimes he alludes to clusters of legends, as in Ayodhyakand[*] , when the people of Ram's city bewail Kaikeyi's harsh demands. The poet makes a brief reference to three classic tales of kings who had to suffer in order to keep their word:

The stories of Shivi, Dadhichi, and Harishchandra

they told one to another.

2.48.5

Religiophilosophical doctrines and categories (such as the "three kinds of pain," "six flavors," and "four kinds of liberation") are frequently referred to as well. Such allusions are like citations of other strands of the great tradition on which Tulsi draws.[13] Thus, without necessarily being difficult from a linguistic point of view, the Manas is often terse and enigmatic, dense and allegorical, and full of references to the epic, Puranic, and scholastic traditions that preceded it; it invites not merely retelling and recitation but also expansion, elaboration, and commentary. We may therefore ask what tradition of lector/expounders of religious texts existed before Tulsidas's time.

Although the Indian tradition of the oral performance of a sacred text dates back at least to the time of the Rg[*]Veda , the poets of which are referred to as "singers,"[14] it is in the later Vedic texts—the Brahmanas and Upanishads—that we first find evidence of a performance milieu involving oral expansion on a sacred text by storytelling and systematic exegesis. In the case of the Brahmanas, the milieu is presumed to be a Vedic school in which students are learning the techniques and mysteries of the sacrificial rites.[15] In the Upanishads, the setting is often identified as a forest hermitage and the text is presented as an oral discourse or a dialogue between teacher and pupil. Another common setting is that of the sacrifice, especially the important royally patronized rites that spanned many days or even months, for which special structures were erected and large numbers of ritual specialists engaged. During breaks in the ritual, it became customary for the Brahmans and their

patrons to pass the time discussing metaphysical questions arising out of sacrificial procedures or listening to the narration of ancient lore.

Thus, the essential components of the Katha tradition were already present by about the sixth century B.C. : the milieu of the religious assembly of "good people" and sages, the presentation of religious truth by storytelling and exposition on older and revered utterances, and the interactive nature of the performer/audience relationship—the unfolding of the exposition as a kind of dialogue. The milieu of the sacrificial session continued to be important for storytelling in the age of story literature proper, the period of the epics and Puranas, and indeed to the present day.[16]

The epics introduce a new class of storyteller, the suta : "a charioteer, driver, groom . . . also a royal herald or bard, whose business was to proclaim the heroic action of the king and his ancestors, while he drove his chariot to battle, or on state occasions, and who had therefore to know by heart portions of the epic poems and ancient ballads."[17] The bard's social status appears to have been relatively low, at least in the eyes of Brahman legalists;[18] yet it is clear that the narrative powers of a talented suta could win respect even from ritual specialists. The opening verses of the Mahabharata describe the arrival of such a storyteller—one Ugrashravas—at a hermitage where a twelve-year sacrificial cycle is in progress. The assembled sages "crowd around" the bard and, with many courtesies, prevail on him to recount his "tales of wonder . . . that ancient Lore that was related by the eminent sage Dvaipayana," which Ugrashravas had himself heard during King Janamejaya's snake sacrifice; the bard consents and the narration of the epic begins.[19]

The Valmiki Ramayana[*] unfolds in a similar bardic context, though without the mediation of a narrator of the suta class. The bards in this case are the twin sons of Ram, Lava and Kusha, who have committed

the epic to memory while living in Valmiki's ashram and are ordered by their teacher to sing it during the intervals in Ram's horse sacrifice. The princes sing the poem, we are told, with sweet voices, to musical accompaniment and to excellent effect; "When the sages heard it, their eyes were clouded with tears and filled with the greatest wonder; they all said to the two, 'Excellent! excellent!"[20]

Although the suta appears originally to have been a low-status performer of martial epic, the Mahabharata bears witness to a revaluation of the role of the text and a corresponding transformation in the status of its performer. Instead of driving a prince's chariot and bolstering battlefield morale with a recitation of past exploits, the suta is occupying a place of honor in an assembly of sages, entertaining and edifying them with stories that are not merely heroic adventures but have come to be regarded as powerful religious narratives. When the Mahabharata declares itself to be "a Holy Upanishad," a "Grand Collection [samhita[*] ], now joined to the Collections of the Four Vedas," and advertises the efficacy of its own recitation ("A wise man reaps profit if he has this Veda of Krishna recited. . . ."),[21] it gives evidence of a process analogous to what anthropologists have termed "Sanskritization": the acquisition of status by an appeal to established standards of orthodoxy or, in the case of texts, by the emulation of the oldest and most authoritative models.

When a text is sanctified, its mediators are similarly transformed. The Mahabharata provides evidence of the involvement of Brahmans with the epic, not only as its appreciative listeners but as its memorizers, performers, and, most significant in the present context, elucidators:

There are Brahmans who learn-the Bharata from Manu onward, others again from the tale of The Book of Astika onward, others again from The Tale of Uparicara onward. Learned men elucidate the complex erudition of the Grand Collection; there are those who are experienced in explaining it, others in retaining it.[22]

Such Brahman storytellers and expounders are sometimes identified by more specific labels; another Mahabharata passage states that when Arjuna went to the forest for twelve months in fulfillment of a vow, his

entourage included "great scholars of the Veda . . . sutas and pauranikas[*] , kathakas as well . . . and Brahmans who gave sweet voice to celestial tales."[23] The forest ashram, as we have noted, was one of the preferred settings for the performance of religious narrative, and this passage highlights the rhetorical skills of the men Arjuna took with him to help pass the time during his year-long vow.

The titles introduced are significant for later traditions of textual mediation. The term suta eventually went out of common use, although the suta role reappeared in the caran[*] and bhat[*] of the Rajput tradition—a professional bard, panegyrist, and genealogist whose duty was to praise the king in court and on the battlefield and to sing versified genealogies on state occasions.[24] More relevant to the present study are the terms kathaka (storyteller) and pauranika[*] (specialist in the Puranas). Hein has shown that by at least the tenth century the former term was considered synonymous with granthika —a "book specialist"—and that the "book" in question was probably a Vaishnava Purana.[25] By the eighteenth century, however, the term kathak had come to refer to a type of storyteller, whose oral renditions of devotional texts were accompanied by gesture and dance and whose art eventually moved from the temple to the royal court, where it influenced the development of a dance style. Today the name of the dance is nearly all that is left of the older art—although many song texts used in the abhinay , or mimed portions of kathak dance, continue to be drawn from Vaishnava devotional literature.[26]

The importance of the other category of performer, the pauranika[*] , grew as the spread of bhakti -style Hinduism created wider audiences for the telling of stories that aroused devotional feelings. Bonazzoli has observed that among the many terms used by the Puranas to refer to their reciters—such as pauranika[*] , vyakhyatr[*] , and vyasa —two basic categories of performers may be distinguished: those who simply recite texts with little or no elaboration and those who translate texts into the

vernacular or otherwise comment on them.[27] The role of the latter performers—for whom the title vyakhyatr[*] is commonly used in the older Puranas, to be replaced by vyasa in some of the later ones—appears to have grown in importance as the Puranic congregation came to include increasing numbers of lower-class and uneducated persons. Derived from the verb vyakhya , "to explain in detail," vyakhyatr[*] may be translated "expounder" or "commentator." A passage in the Padma purana[*] (c. 750 C.E. ) praises the vyakhyatr[*] in exalted terms and directs his patrons to honor him with gifts of clothing, scent, and flowers. It attributes the indispensability of such an expounder to the exigencies of the present Kali Yuga, in which even Brahmans are not as knowledgeable as they formerly were and ancient texts are no longer properly understood.[28] That the audience's ignorance is largely linguistic is suggested by other verses, which describe the vyakhyatr[*] as translating into local languages the Sanskrit of the Puranic sages. Another verse describes the manner in which such an expounder is to approach the text: "Let the wise [man] read slowly and slowly comment on it, having divided the reading of the sloka and having established a meaning in his mind."[29] The use of the gerund vivicya (having divided, or having split) is significant, particularly in view of the later replacement of the term vyakhyatr[*] with vyasa , which likewise means one who "separates" or "divides." Given the conventions of written Sanskrit—the absence of word breaks, the freedom of word order, and the joining of words into compounds—"division" can of course refer literally to the process by which the reader disassembles a sloka in order to decode its meaning. But the notion of "dividing" has additional significance and can help us to understand the nature of the expounder's work, which is not merely translation but "elaboration."

The term vyasa naturally recalls the legendary sage Krishna Dvaipayana, or Veda Vyasa, who is said to have divided the one Veda into four in order to make it more readily comprehensible to the people of this dark age. His creativity did not end there, however; he is also credited with the authorship of the hundred thousand couplets of the Mahabharata and the narration of many of the Puranas themselves, and it is often asserted that this voluminous story literature was in fact another recasting of the Veda to suit the needs of the time. The fact that

"division" appears to be linked, in Hindu thought, with "elaboration" and "expansion" becomes clearer if we recall that in many Indic cosmogonic myths the act of creation is accomplished by means of a primordial separation or division.[30] To "divide" can thus mean to creatively elaborate, and in contemporary usage a vyas[31] is one who artfully elaborates on a sacred text, generally focusing on a small part of it (and then often systematically "dividing" it into its components—a type of exposition that is still called vyakhya ) in order to bring out its profound or hidden meaning. Such a performer is viewed as a spiritual descendant or even a temporary incarnation of Veda Vyasa, who was himself an incarnation of Vishnu.[32] A verse in the Bhavisya[*]purana[*] (c. 1200 C.E. ) describes the vyas as expounding from a special elevated seat (vyaspith[*] )—a position of honor and authority in the assembly of devotees.

That the Puranas for the most part lack commentaries is very striking and has often been remarked on.[33] Bonazzoli suggests that this may be due to the fluid nature of the texts, which were continually being rewritten according to the interpretations of sectarian groups (sampradayas ). According to his view, "commentary" was continually incorporated back into "text."[34] We can further observe, however, that the tradition of public exposition provided an ongoing, living commentary in which not only expounders but also audience members might participate. A passage in the Padma purana[*] depicts a recitation program beneath a street-corner mandap[*] in which a listener closely questions a pauranika[*] , who is then obliged to elaborate on his commentary. Similarly, the Bhavisya[*]purana[*] mentions "manuals of explanations" (vyakhana-samgraha[*] ) that may have been prepared to assist the less prepared ex-

pounder.[35] Such examples remind us that the Puranic congregation was not a mere passive audience but played its own role in the explication of scripture. The privilege of audience members to question, raise doubts, and "comment" on the text in their own fashion remains an important feature of Manas exposition, and even the "manuals" referred to above have their counterparts in the sankavalis[*] (collections of "doubts" or "problems," together with their solutions) assembled for the assistance of expounders of the Hindi epic.

In a recent essay Thomas Coburn attempts a "typology of the Word" in Hindu life, distinguishing several classes of religious utterance that all tend, in Western scholarly studies, to be subsumed under the generic term "scripture." First, he notes the existence of "frozen" texts (such as the Rg[*]Veda ), which are "intrinsically powerful . . . and worthy of recitation, regardless of whether they are 'understood.'" These he contrasts with texts that are important primarily because of their stories—for example, the Ram and Krishna legends in various literary versions. Coburn also identifies other categories, but in the second stage of his analysis he reduces them all to two, for which he offers the labels "scripture" and "story." The former is "eternal and immutable," the latter "dynamic . . . spawning all manner of elaboration."[36] The Rg[*]Veda would certainly seem to belong to the former category, and the Puranas to the latter; but the Manas —along with other seminal bhakti works that have acquired a kind of canonical status within their traditions—seems to belong in both categories. On the one hand, the epic early acquired a fixity that resists interpolation and a status that makes possible the kind of ritualized recitations already described, in which the text is important more as mantra than as story. On the other hand, the meaning of this text is important to its audience; that meaning is elucidated primarily by oral performance forms that are inherently dynamic and allow for and indeed encourage the introduction of much contextual material. Coburn's two categories highlight the dual role that, as we shall see, oral expounders have historically played in relation to the epic: of guarding the purity of the mul (root, or Ur-) text, the text as scripture; and of creatively retelling and expanding on it in oral performance, once again bringing it to life as story.

The Manas-Katha Tradition

Tulsi the Singer

Although there is no reliable documentation of performance of the Manas in Tulsidas's time, it seems reasonable to assume that as the fame of the work spread, it came to be systematically expounded in Vaishnava devotional assemblies. The hagiographic tradition describes Tulsidas as performing his own works, and even though the authenticity of some of these sources (such as the Mulgosaim[*]carit , discussed earlier) may be questioned, the portrayal of Tulsi as a devotional singer seems plausible, particularly in light of certain references in his poetry. In some of the introspective and confessional songs of the Kavitavali and the Vinay patrika , probably composed late in the poet's life,[37] Tulsi complains of his own hypocrisy, lamenting that, though inwardly a sinner, he "fills his belly" by singing Ram's praises.[38] Such verses suggest that, like many contemporary sadhus, he may have derived a meager livelihood from the offerings made by devotees at the conclusion of bhajan or Katha programs.

Another glimpse of Tulsi as a performer is supplied by the Gautamcandrika , a work purportedly composed within a year of Tulsi's death by Krishnadatt Mishra, the son of one of Tulsi's intimate companions and ostensibly an eyewitness to many of the events he records. One passage describes Tulsi's performance of a Visnupad[*] (the reference may be to Vinay patrika , which is an anthology of pads , or short lyrics) and its popular reception:

One night many sadhus came

and Tulsi sang a new Visnupad[*]

to drive away intellectualism and establish bhakti .

The night passed, but no one noticed.

Tulsi went to the temples,

prayed and sang the Visnupad[*] .

Having listened with devotion to this new song

men and women began singing it everywhere.

On every ghat, in houses, lanes and squares,

the Visnupad[*] spread throughout Kashi.

The conceited traditionalists became offended,

[as did] the hypocritical goswamis of the city.[39]

Other hagiographic works depict Tulsi as both a singer and a kathavacak . A famous story of Tulsi's meeting with Hanuman in the context of a Katha performance is found in Priyadas's commentary on the Bhaktamal , composed some ninety years after Tulsi's death.[40] The relevant verses, in which a ghost addresses Tulsi, read:

Your Ramayan Katha is elixir to Hanuman's ears.

He comes first and departs last, though in repugnant guise.[41]

During the four lunar months of the rainy season (caturmas ), when travel became difficult, mendicants would traditionally remain in an ashram or religious center, where lay devotees would provide for their maintenance. Among the favored activities for these months were satsang[*] and the hearing of Katha . The Mulgosaim[*] carit describes Tulsi's activities during one caturmas as follows:

He stayed there for the rainy season

and daily told the Ram-katha with a glad heart.

The saints who dwelt in that forest listened daily

and listening, experienced great delight.[42]

The First Retellers

I have noted that a Katha always has a principal srota , or listener, who should be one "worthy of receiving the Katha " (katha-adhikari ), as Tulsi himself suggests in Uttar kand[*] :

A listener who is wise, virtuous, pure,

a lover of Katha and servant of the Lord—

O Uma!—finding such a one,

a good man reveals even the most secret things.

7.69b

The chief listener's qualifications are important because he can become another link in the chain of transmission of the Katha ; hence the hagiographic tradition's concern with the identity of Tulsi's first hearers. The Mulgosaim[*]carit identifies four original srotas , one of whom is then said to have recited the epic "over the course of three years," which suggests the kathavacak style of exposition in daily installments. Other traditional accounts of the early performance of the epic paint a similar picture of extended recitation in the satsang -assemblies of Vaishnava holy places. A twentieth-century Prasnottari (question-and-answer manual) on the propagation of the Manas lists nine early "tellings" and reveals, if not historical exactitude, at least the tradition's characteristic concern with place and occasion of narration as well as its concept of the extended and elaborate nature of Katha .

Question: Who was the first Manas expounder?

Answer: (1) Swami Nandlal of Sandila and (2) Swami Ruparun of Mithila. These two swamis had the good fortune to hear the recitation of the Ramcaritmanas from Goswami at Tulsichaura, Ayodhya. One of them recited the Manas-katha over the course of three years to Raskhan at Vrindavan, on the banks of the Yamuna, and the other recited it to Sabhal Singh Bhumihar on the banks of the Bagmati.

(3) At Chitrakut on the banks of the Mandakini, a second Tulsidas and (4) his pupil Kishoridas, in the midst of an assembly of saints, completed the entire Katha of the Manas in twelve years.

(5) In Kashi on the banks of the Ganga, Baba Raghunathdas told the Katha of the Manas in seven years and (6) in Panchavati on the banks of the Godavari the poet Moreshvarpant told it in nine years.

(7) In Ayodhya on the banks of the Sarayu, Benimadhav Das . . . and (8) at the confluence at Varahkshetra his pupil Keshavdas systematically related this Katha in ten years to Manas lovers. (9) At Soron on the banks of the Ganga, Mahatma Tulsidas Gosai and his son Janaki Gosai together told the Katha in five years during a sacrificial session.[43]

Such traditional accounts and the guru-disciple lineages offered by later expounders to assert their direct link with Tulsidas are among the few extant clues to what must have been a flourishing tradition of Manas performance during the first century and a half following the poet's death. From the latter part of the eighteenth century, however, it becomes possible to trace the development of the Manas-katha tradition, in part through manuscript commentaries on the epic composed by eminent Ramayanis. Substantial collections of these works may be found, for example, in the palace library at Ramnagar (Banaras) and in religious establishments in Ayodhya, but they have largely been ignored by academic scholars. Probably the most substantial treatment of the commentarial tradition (which, as will be seen, is synonymous with the Katha tradition) is an article by Anjaninandan Sharan, "Manas ke pracin tikakar[*] " (Early commentators on the Manas ), which appeared as an appendix to the special Manas issue of Kalyan[*] in 1938. The author, a scholarly sadhu of Ayodhya, was the compiler of the twelve-volume Manaspiyus[*] (Nectar of the Manas ), an encyclopedic commentary that incorporated the insights of many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Ramayanis and about which more will be said shortly. Although the Kalyan[*] article contains many gaps, it is still a rich source of historical and legendary material.[44] The account presented here necessarily relies heavily on Sharan's article, supplemented when possible by material from other sources.[45] But before I embark on this folk history of Manas commentary, some clarification of terminology is useful.

Indigenous Exegetical Terms

Although it is hardly possible to avoid using the term "commentary" in reference to written works in the Manas tradition, the reader's understanding of this term should be tempered by reference to the Sanskrit/

Hindi terms for which it is only a partially adequate substitute. Both tika[*] and tippani[*] , for example, can mean "annotation" or "note," and many commentaries originated in the kharra , or "rough notes," made by expounders in the margins of their manuscripts of the Manas —notes intended as aids in interpreting difficult lines in oral exposition. Such annotations could rarely be understood without a teacher to expound them, and this was true even in the case of some nineteenth-century published "commentaries."[46] Another word often translated as "commentary" is tilak , and here a primary meaning is "ornament" or "embellishment." Indeed, both tika[*] and tilak also refer to the auspicious, often sectarian symbols with which Hindus adorn their foreheads. The purpose of a written tilak —at least within the bhakti tradition—is often as much "ornamental" as it is explicative; it is primarily an embellishment and expansion on the text rather than an intellectual explanation of it.

The interpretation of a given Manas verse by an individual expounder is usually referred to as a bhav —a "mood" or "feeling," an indicator of its essentially affective nature. A vyas in performance may cite the interpretations of a number of earlier expounders, introducing each somewhat as follows: "Concerning this verse, Pandit Ramkumar-ji had this bhav . . . ." The bhav of another vyas may then be presented in turn; the fact that it differs greatly from Ramkumar's or even contradicts it will not disturb either performer or audience. Conflicting "feelings" can still be savored by listeners, even though they may find that one bhav comes closer to their own feeling about a line than another does.

This tolerance for conflicting interpretations extends even to the basic structure of the narrative, since the Manas is an authoritative but

not a definitive text of the Ramayan tradition and since people typically know many Ramayan-related stories that are not recounted by Tulsidas. I once heard the Banarsi vyas Shrinath Mishra digress while expounding the Manas to relate an incident from Krittibas's Bengali version of the story concerning a long conversation between Ram and Ravan on the battlefield, where the latter lay dying from his wounds. This incident not only has no parallel in the version of the story best known to Shrinath's audience but seriously contradicts its narrative and chronology. It depicts Ravan, just before his death, as a devotee of Ram, and their conversation as extended and tender; in Tulsi's account Ravan remains an enemy to the last (although his soul wins final salvation by Ram's grace) and his death in battle is instantaneous. In retelling this story, the vyas advised his listeners not to worry over the narrative details but to "just savor Krittibas's bhav a little!" Moreover, it is understood that there is no limit to the number of bhavs that can be drawn from the epic or even from one of its verses, as some expounders have tried to demonstrate by presenting a stupefyingly vast number of interpretations for a single line.[47]

If we understand the terms tilak and tika[*] , at least in the context of the Manas , to refer essentially to emotionally flavored "re-presentations" of the text, we can better explain the wide range of works that may be grouped under these terms—ranging from brief verse-by-verse glosses in modern Hindi prose, offering no elaboration (although interpretation is necessarily involved in any transposition from poetry to prose), to multivolume works such as the Vijayatika[*] of Vijayanand Tripathi, in which each verse is followed by an extended analysis that may fill several pages.[48] In the same way, Katha performances may consist of little more than a recitation of the text with a brief prose explanation for each line or may involve elaborate and extended exposition in which, for example, a single line is discussed for many consecutive days.

The Rise of Royal Patronage

Although the tradition of oral exposition of religious texts—notably of the Vaishnava Puranas—had developed in northern India before the advent of Islamic rule, the establishment of Muslim hegemony created

conditions favorable to its spread. The congregational expression of religious feelings through bhajan, kirtan , and Katha required no elaborate superstructure of temples and shrines, which could become targets for the iconoclasm of the new rulers. Vaishnava storytellers and expounders were often wandering sadhus, whose activities were likewise difficult for the state to regulate. Moreover, the religious philosophy of Katha tended to emphasize spiritual egalitarianism and hence appealed to people of low social status; it served to counter the social appeal of Islam and may have encouraged the patronage of wealthier, caste Hindus alarmed at the conversion of low-caste and untouchable groups.[49]

The development of present-day styles of Manas exposition can be dearly traced only from the period of the define of centralized Muslim rule in northern India—that is, from the eighteenth century. The rapid dissolution of the Mughal empire following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 led to the rise of many independent and semi-independent kingdoms, some under Hindu rulers. Even though Hindu courts of the period remained heavily influenced by Islamic cultural models, they also sought to express their identity and independence by affirming Hindu traditions of kingship and social order. This need to reassert a Hindu identity became more acute in the nineteenth century, when the Mughal imperial mantle passed to a far more self-assertively foreign regime, which engaged in an increasingly harsh critique of Hindu religion and culture—the British Raj.

The Vaishnava devotional tradition had for centuries been a major source of religious inspiration throughout the Hindi-speaking regions. The cult of Krishna had developed a spiritual center in the Braj region as well as important connections with Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Bengal; the cult of Ram had its geographical locus in the area today comprising eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and northern Madhya Pradesh, the legendary heartland of the narrative. Geography plays its part in bhakti —one expects to find a preponderance of Krishna worship in Vrindavan and of Ram worship in Ayodhya—and so it may seem only natural that the Hindu dynasties that arose in the eastern Ganges valley in the eighteenth century were inclined to patronize Ram-related traditions. But an additional reason for this preference may lie in the fact that the theology of Krishna bhakti had, during the centuries of Muslim rule, come to be almost exclusively focused on the pastoral and extrasocial myth of the

divine cowherd of Vrindavan and so no longer presented a model of kingship for this-worldly rulers.[50] In contrast, the Ram tradition had preserved a strong sociopolitical strand, expressed most clearly in the vision of Ramraj and in Ram's role as the exemplar of maryada , a term that implies both personal dignity and social propriety. The accessibility of the tradition was enhanced by the expression of these ideals in a brilliant vernacular epic that had already won a vast following throughout the region. Accordingly, it was to Ram and the Manas that many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Hindu rulers turned for a validating model of temporal authority.

From the limited evidence available, we may speculate that the early propagation and patronage of the Manas was primarily the work of sadhus and middle-class people—merchants and petty landowners—and that Tulsi's epic did not initially have a strong appeal for the religious and political elite. Beginning in the latter half of the eighteenth century, however, there was a great surge in the royal and aristocratic patronage of the Hindi epic, reflected in the collection and copying of manuscripts at courts such as Rewa, Dumrao, Tikamgarh, and especially Banaras and in the encouragement of oral expounders and the commissioning of written commentaries by the most influential among them. Not surprisingly, royal patronage appears to have had the effect of awakening greater interest in the epic among Brahmans, so that the work of exposition and commentary came increasingly into the hands of religious specialists.

The chronology of the Banaras maharajas, who were the most influential patrons of the Manas during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, provides a convenient time line against which to view other developments in the tradition. The founder of the dynasty, Mansaram Singh, came to power in 1717 and ruled until 1740. By all accounts he was an ambitious local chieftain of doubtful pedigree, although his descendants claim the status of Bhumihar Brahmans (Brahmans "of the land"). The family conformed to the classic pattern of the nouvel arrive[*] in Indian politics: rising from obscure beginnings to a position of temporal power and securing social and ritual status by patronizing a validating religious tradition. Mansaram's son, Balvant Singh (1714-70), oversaw the con-

struction of the Ramnagar fortress, across the Ganga and slightly upstream from Banaras city, on bluffs rising to the south. Besides occupying a strategic location safe from the annual floods that inundate the low-lying areas to the north, the fortress is popularly believed to mark the site at which Krishna Dvaipayana Vyasa, the legendary "divider" of the Veda and author of sacred literature, performed austerities and composed his Mahabharata . A small temple on the western rampart overlooking the river enshrines a Shiva linga said to have been consecrated by Vyasa himself. Legend holds that Balvant Singh constructed the palace around this shrine. This temple has for many generations remained in the custodianship of a family of Ramayanis in the service of the maharaja. The male members of the family chant the Manas during the annual Ramlila ; some also expound the epic at other times of the year and thus fulfill the role of vyas in the special sense explained earlier. It seems fitting that the Vyas Temple, which claims a direct link with the archetypal mediator of sacred text, should serve as the symbolic cornerstone of a palace whose occupants have long affirmed their royal status through the mediation of the Manas epic.

The great flowering of Manas patronage at the Ramnagar court began in the reign of Balvant Singh's grandson, Udit Narayan Singh (1783-1835), who commissioned the massive Citra ramayan[*] (a lavish illuminated manuscript of the epic) and reorganized the local Ramlila into an elaborate month-long performance cycle. His son, Ishvariprasad Narayan Singh (1821-89), was himself the author of a commentary on the epic and made the court the preeminent seat of Manas patronage and scholarship; his reign has been called the "Golden Age of the Manas ."[51] The legendary Ramayani-satsangs he sponsored were graced by the "nine jewels" of the court—the most renowned Manas scholars of the day. Ishvariprasad's successor, Prabhu Narayan Singh (1855-1931), arranged for the publication of the great three-volume commentary commissioned by his father. By his time, however, the availability of printed editions had begun to create new audiences and patrons for Manas exposition, and the importance of royal patronage was starting to decline, although the family-sponsored Ramlila remained the most prestigious of Manas stagings. The proliferation of printed editions of the epic, many of which appeared with tikas[*] composed by contemporary Ramayanis, helped spread the fame of influential expounders and contributed to the growth of an audience that was both more knowl-

edgeable with respect to the text and more discriminating with respect to oral exposition.

Even though no other court could match the luster of Kashi, with its ancient sacral status and its intimate associations with both the principal narrators of the epic—Tulsidas and Shiva—other princely states were also active in Manas patronage. Of special note was the court of Rewa (on the Uttar Pradesh-Madhya Pradesh border) under Vishvanath Singh (1789-1854) and his son Raghuraj Singh (1823-79), both of whom were poets. The former is credited with thirty-eight works, nearly all on Ram-devotional themes, including a commentary on Tulsi's Vinay patrika ; the latter, who was a close friend of Raja Ishvariprasad of Banaras, was only slightly less prolific, with thirty-two poetic works to his credit.[52] Another center of Manas patronage was the court of Dumrao, near Baksar in Bihar. Its ruler, contemporary with Udit Narayan of Banaras, was Gopal Sharan Singh, who patronized the legendary expounder Shivlal Pathak and himself composed a tika[*] on the Manas in the 1830s.

The cultural challenge presented by British rule was undoubtedly one factor in causing these nineteenth-century princes to turn to the study and promotion of their cultural epic. It is also worth noting, however, that it was the "Pax Britannica" that relieved these small kingdoms of the sovereign Kshatriya responsibility of engaging in incessant internecine warfare and permitted their lords the leisure to compose poetic commentaries, make pilgrimages to Ayodhya and Chitrakut, and identify with one another not as enemy sovereigns but as fellow devotees, defenders of the faith, and patrons of an emerging "Hindu renaissance."[53]

The Tulsi-Parampara

The guru-sisya[*] (teacher-disciple) relationship is as central to the art of Katha as it is to other Indian performance traditions, and most expounders conceive of themselves as belonging, however symbolically, to a parampara (chain, or succession) that ultimately extends back to the very sources of the tradition. Anjaninandan Sharan identifies two main

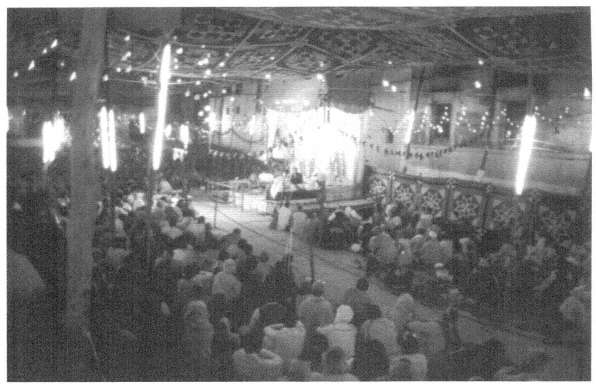

Figure 15.

The Tulsi-parampara according to Anjaninandan Sharan.

Source: Sharan, "Manas ke pracin tikakar[*] ," 910. Names followed by an asterisk are

those of famous expounders to whom additional reference is made in the text.

"schools" of Manas interpretation, which may be labeled the "Tulsi" and the "Ayodhya" traditions respectively. The first traces itself back to Tulsidas (and ultimately to Shiva, the first narrator of the Manas ), but historically it can be most clearly traced through its two branches, which represent the traditions of Shivlal Pathak and Ramgulam Dvivedi, influential expounders of the early nineteenth century. Banaras was the most important center for this tradition, and most of its major figures enjoyed, at one time or another, the patronage of the Ramnagar kings. The Ayodhya parampara , on the other hand, was the Katha tradition of the various Ramanandi ascetic lineages that had their base in Ram's holy city; Sharan, himself an Ayodhya sadhu, did not attempt to trace this tradition back to the time of Tulsidas, but each of the sadhu lineages has its own chain of transmission, usually leading back to Ramanand and sometimes including Tulsi, if the sadhus claim him as a member of their order.[54] In the pages that follow, I discuss figures from both traditions as well as a number of commentators who do not seem to belong to either; the majority of names that I introduce, however, belong to the Tulsi-parampara . Accordingly, it is useful to begin with a chart of this tradition (fig. 15), based on one in Sharan's 1938 article but with a few additions to bring it up to date.

This diagram cannot be taken as a historical or even a strictly chronological schema; rather it is a symbolic representation of a tradition as some of its practitioners conceive of it. In certain cases, successive figures on the chart were indeed connected by a teacher-disciple relationship that spanned many years of intensive instruction in Manas interpretation. In other cases, a pupil's contact with a given teacher may have been fleeting; he may have had the darsan (auspicious sight) of the guru, perhaps heard him expound on several occasions, and received (or felt that he received) his blessing (asirvad ). The situation is complicated by that fact that a pupil may have several gurus: a siksa-guru[*] , who imparts teachings; a diksa-guru[*] , who initiates and bestows a mantra; and additional gurus for specialized instruction. He may choose to place himself in the lineage of any or all of these.

In this context, it is important to understand that it is not primarily intellectual knowledge of empirical information that is communicated through the teacher-pupil succession, but rather authority (adhikar )—the authority to practice a particular sadhana and repeat a mantra, or to interpret and expound a particular text. Such authority may also be the

outcome of "grace" (krpa[*] ), and the guru who imparts it may not be a human being at all; many expounders attribute their understanding of the Manas to the grace of Hanuman, the special patron of their tradition, bestowed in an extraordinary spiritual encounter.

Mahant Ramcharand as and Jnani Sant Singh

It is said that the first "commentary" on the Manas was a Sanskrit translation of the poem made in about 1603 by a disciple of Tulsi, Ramukar Dvivedi.[55] The first complete Hindi tilak on the epic, however, is not thought to have been composed until nearly two centuries later and is credited to Ramcharandas of Ayodhya (not included in figure 15), a Ramanandi sadhu. Born in a Brahman family in the area of Pratapgarh, U.P., in about 1760, Ramcharandas is said to have been in the service of a local raja for some time; but a spiritual experience caused him to renounce the world and go to Ayodhya,[56] where his humility and service to other sadhus earned him the title Karunasindhuji—"the ocean of mercy." Eventually he rose to a position of authority as mahant , or leader, of his own gaddi (literally "couch" or "throne" but by extension a religious establishment that contains the "seat" of a powerful mahant ) on Janaki Ghat, where he gave Manas-katha daily to great numbers of sadhus and lay devotees. It is said that Asaf ud-Daula, the Muslim nawab of Oudh, made a gift of several villages for the maintenance of Ramcharandas's establishment. Raja Vishvanath Singh of Rewa was so taken with his Katha that he urged the mahant to commit it to writing and provided twelve pandits to assist in this task. Their labors, it is said, occupied twelve years and resulted in the tilak entitled Ramanandlahari (Waves of the joy of Ram), which was completed in

about 1805 and published many years later.[57] It divides the epic into episodes, each of which is referred to as a "wave" (tarang[*] ); the image is of course derived from Tulsi's theme-allegory of the Manas Lake. According to Sharan, it is composed in rustic dialect and does not provide commentary on "easy" or straightforward verses but only on those that are poetically or theologically complex. He adds that when the book was completed, "its Katha was expounded from beginning to end, on Janaki Ghat in the assembly of saints, over the course of three years."[58] Thus, the tilak , like its source text, became the basis for expanded oral exposition; as we shall see, this has remained a primary function of Manas commentaries.

A further point of interest regarding this early commentary is that Ramcharandas claimed, in his opening verses, to have before him a manuscript in Tulsi's own hand. Such an "authentic" or autograph (pramanik[*] ) manuscript remains to this day the Holy Grail of Manas scholarship;[59] early expounders and commentators, not yet influenced by Western textual criticism, put great emphasis on obtaining the earliest and most authentic manuscripts so as to identify the mul text and purge it of any "interpolations" (ksepak[*] ).[60] As I have already suggested, these scholars were only carrying out what they regarded as Tulsi's injunction that they serve as "diligent guardians" of the Manas Lake.

Another early nineteenth-century figure who does not appear on the parampara chart—who indeed seems to have been something of an anomaly in the Manas tradition—was Jnani Sant Singh, known as Panjabi-ji, a Sikh who was the mahant of an establishment known as Nanakshahi in the vicinity of Amritsar. According to his own account, he was ordered by Hanuman in a dream to compose a tilak on Tulsi's

Ramayan: "I replied that I didn't know that language [Avadhi] at all. Then the order came to recite it 108 times. 'From the power of that, you'll gain much knowledge of the language, and the bhav of the text will dawn on you; that you must set down in the form of a tilak .'"[61] The mahant carried out the order, and the result was the commentary known as Bhavprakas (effulgence of feeling), composed in the early 1820s in mixed Panjabi/Hindi dialect and eventually published by Kadgavilas Press of Bankipur, Bihar (1897). Sharan gives high praise to this tilak , and his comments reveal a Manas connoisseur's point of view, especially with regard to the importance of originality: "In the presentation of interpretations and in the resolution of doubts, this commentary is in a class by itself; no one else's influence is to be found here."[62] That Panjabi-ji should have composed this work at all is evidence of the growing influence of the Manas in the northwest by the late eighteenth century.

Shivlal Pathak and Ramgulam Dvivedi

Roughly contemporary with Mahant Ramcharandas and Jnani Sant Singh were Shivlal Pathak and Ramgulam Dvivedi; with these men the two main branches of the Tulsi-parampara enter the historical record. Each had an extraordinary impact and came to be regarded as the founder of a tradition of Manas interpretation. Pathak's tradition eventually died out, but Ramgulam's, which branched further into two "schools," remains very much alive and represents the dominant tradition of Katha in contemporary Banaras.

Shivlal Pathak was born in a village in Gorakhpur District in 1756.[63] Because of an unhappy relationship with a stepmother, he left home at the age of nine and went to Banaras, where he worked for some time in a sweetseller's shop. Unusually bright and studious, he was eventually accepted as a student by a renowned pandit; in due time he too became famous for his knowledge of Sanskrit literature and acquired students of his own. There is a tika[*] on the Valmiki Ramayana[*] composed by him, dated 1818. As a Sanskrit pandit he was, according to Sharan, initially opposed to the Manas . "His attitude was the same as that of the great Sanskrit pandits of Goswami's time. He was an enemy of the Hindi language and never read or listened to Tulsi's Ramayan. But the Lord

had other plans [as Pathak later wrote]—'In my mind was one idea; in God's, quite another.'"[64]

His "conversion" came suddenly, through the influence of one of his own students. Paramhams Ramprasad was a sadhu who had come from Ayodhya to seek training in Sanskrit literature, the better to enrich his Katha with quotations from appropriate Puranas and sastras . Knowing Pathak's attitude toward the Manas , he was careful to conceal his intent from his guru, but on holidays he would expound to his fellow students in some private place. Sharan offers his own vivid Katha on this famous story:

One day, the guru went off to Ramnagar, and Paramhams-ji, knowing that Pathak would not be able to return that day because of heavy rains, gave Katha in the school itself. It was such a Katha and such an assembly that all the students, intoxicated with love, forgot themselves in the hearing. No one even noticed that the sun had gone down. Pathak returned and, seeing everyone lost in devotion, stood by the doorway and watched and listened. After a little while the Katha ended and everyone rose to go home. Seeing their guru leaning against the wall in the doorway, the student audience fled in terror, supposing that now that he knew, he would fly into a rage. But Paramhams-ji guessed something of his condition. He fell at Pathak's feet and saluted him, saying, "At the urging of some devotees, the Lord's Katha was started here. You came and modestly remained standing outside. A great wrong has been committed; kindly be merciful!" Hearing this humble entreaty, Pathak threw himself full length at Paramhams-ji's feet and clutched them fervently, crying, "This head that has never bowed to anyone, has today become a bee on your lotus feet; this is the result of that elixir of Ram that you dispense." Paramhams-ji lifted him up and embraced him. . .. Guru became disciple and disciple, guru.[65]

At Ramprasad's order, Pathak is said to have undertaken 108 nine-day Manas recitations, as a result of which the hidden meanings of the epic were revealed to him and he became an accomplished kathavacak . Another tradition holds that when he first expounded in Banaras, the effect on the audience was so powerful that 75,000 rupees were offered at arti time, all of which Pathak placed at his guru's feet. It is certain that Pathak enjoyed the favor of Raja Udit Narayan Singh of Banaras and Raja Gopal Sharan Singh of Dumrao, in whose court he stayed for some time. He composed several works on the Manas , all in verse; the most famous is Manasmayank[*] (Moon of the Manas ), which consists of 1,968 couplets, each attached to a verse in the epic. The style of these verses

has been described as "enigmatic" or "riddling" (kut[*] ); they cannot be readily understood. Like many premodern "commentaries," Pathak's was actually an outline for oral exposition to his own students and audiences. Sharan records a tradition that Pathak was able to expound each kut[*] verse from five different perspectives: Vedic or "scriptural" (vaidik ); yogic; logical or rational (tarkik[*] ); metaphysical (tattvik ); and worldly or practical (laukik ). Some of Pathak's interpretations were beyond the grasp even of his own students, however, and in Sharan's view many of his most profound ideas "went with him" when he died. Nevertheless, some later expounders continued to reckon themselves in his tradition, and a published version of Manasmayank[*] appeared in 1920, with a prose tika[*] by Indradev Narayan that attempted to unravel some of Pathak's riddles.[66]

Even more renowned than Shivlal Pathak was Ramgulam Dvivedi of Mirzapur; the extent to which popular tradition associates him with the Manas is suggested by a folk saying, "Valmiki was reborn as Tulsi, Tulsi as Ramgulam."[67] I have been able to find no birthdate for him, but he was active c. 1800-1830 and like Pathak was associated with the court of Udit Narayan Singh; a manuscript of the Manas copied by him in 1818 is in the palace library at Ramnagar. Like Jnani Sant Singh, he is said to have become a kathavacak through Hanuman's intervention, which came at a time when he was working as a manual laborer to support his family. Sharan and Singh recount essentially the same story:

About two miles outside Mirzapur and on the other side of the river was a Hanuman temple; a daily visit there was his firm practice. One day by chance he forgot to go. At night when he remembered, he immediately jumped up and set out. It was raining hard, and the Ganga was in spate. There was no ferryman on the bank. Bravely resolving to swim across, he threw himself into the torrent. Halfway across, as he was sinking, Hanuman seized his arm and saved him, he gave him darsan right there, brought him to the bank, and bestowed his blessing: "In your Katha , ever fresh and original interpretations will pour from your lips."[68]

Singh adds the interesting detail that Hanuman expressly forbade Ramgulam to compose any written commentary; the extraordinary interpretations (bhav ) were to come strictly "from his lips." Later, when Ramgulam discovered that some of his students were taking notes on his Katha , he is said to have cursed the writings, declaring that anyone who read them would go blind; some eighty years later, the great expounder Ramkumar Mishra, grand-pupil of Ramgulam, attributed his failing eyesight to the fact that, in his ceaseless quest for deeper insight into the Manas , he had dared to consult the forbidden notebooks. In any case, it is certain that no major tika[*] ever appeared under Ramgulam's name. However, he assiduously assembled the best available manuscripts of Tulsi's works. An edition of the Manas prepared by him and published by Sarasvati Press, Banaras, in 1857 was considered by Grierson (writing in 1893) to be the "most accurate" then available.[69]

Ramgulam is the first expounder of whom we note claims concerning a very extended elaboration of small passages of the text. One story tells of a meeting between the expounder and Maharaja Vishvanath Singh of Rewa at the Kumbha Mela festival in Prayag (Allahabad). When Ramgulam graciously offered to speak on any topic of the king's choosing, the raja immediately quoted the first line of the "praise of the divine name" (nam-vandana ) section of Book One.

I venerate Ram, the name of Raghubar,

the cause of fire, sun, and moon.

1.19.1

The vyas agreed to expound on this verse the following day from 3:00 to 6:00 P.M. ; but then, according to Sharan,

he went on for twenty-two days, expounding this one line with ever-new insights; and whatever bhav he would put forth on one day, he would demolish the next, saying that it was not right. Finally on the twenty-third day the raja, filled with humility, said, "You are indeed a fathomless ocean of this Manas , and I am only a householder, with all sorts of worries on my head. It is difficult for me to stay on here." Then with much praise he requested leave to depart and returned to Rewa.[70]

Other stories link Ramgulam with his contemporary Ramcharandas of Ayodhya. It is said that the two expounders became so fond of each other that they made a pact to depart from the world at the same time. When he felt that his end was near, Ramcharandas repaired to his seat

on Janaki Ghat and gave a last katba in the midst of a great assembly of devotees. Just as he was finishing, a messenger arrived with a note from Ramgulam, also on his deathbed, asking if he remembered their agreement; the mahant smiled with pleasure at his friend's punctiliousness and peacefully breathed his last.[71]

Raghunath Das and Kashthajihva Swami

Two other illustrious expounders of the first half of the nineteenth century need mention here, even though they do not find a place on the parampara chart. Raghunath Das "Sindhi" (fl. c. 1835-55) was the author of Manasdipika (Lamp of the Manas ), one of the most popular and frequently reprinted of nineteenth-century commentaries.[72] His was one of the first editions to feature extensive accessory material, including a glossary and notes on mythological references, such as are standard in modern popular editions. The tika[*] itself was brief and essentially a gloss on the verses.

Raghunath's contemporary, Kashthajihva Swami (also called Dev Tirth Swami, died c. 1855), holds a place of importance in Banaras tradition and brings us into the period of Ishvariprasad Narayan Singh (1821-89), his patron and pupil. There are various explanations of how this sannyasi got his peculiar name ("wooden-tongued" swami);[73] in any case, it is certain that he was an influential figure at the Ramnagar court. An accomplished poet with a unique style, he composed some fifteen works as well as more than fifteen hundred songs, several hundred of which concern interpretive problems in the Manas .[74] Like many other nineteenth-century Ram devotees, he was a srngari[*] (a practitioner of the mystical/erotic approach to bhakti )[75] and was closely involved in

the development of the Ramnagar Ramlila pageant, the performance script of which still contains a number of his songs. At Ishvariprasad's urging, he wrote a short tika[*] entitled Ramayan[*]paricarya (Service of the Ramayan), which the maharaja then expanded with his own Parisist[*] (Appendix). These texts, however, like Shivlal Pathak's verses, were little more than notes for oral exposition and were written in an obscure style; to clarify them, Baba Hariharprasad, a nephew of the maharaja, who had become a sadhu, composed an additional appendix entitled Prakas , or "Illumination." The complete tilak with its grand composite title (Ramayan[*]paricaryaparisist[*]prakas ) was eventually published in two volumes by Khadgavilas Press (1896-98) and was held in high regard by Ramayanis of the period.

Vandan Pathak, Chakkanlal, and Ramkumar

The next generation of expounders brings us into the twentieth century and includes the "founding fathers" of contemporary Banaras Katha , all represented on the parampara diagram. Vandan Pathak was born in Mirzapur in about 1815 but spent most of his long life (according to Sharan, he died c. 1909) at Ramkund, in the Banaras neighborhood known as Laksa. He composed a dozen works, including a Manassankavali[*] (collection of epic-related "problems" with their solutions or explanations). Most of his writings were based on the copious jottings he made in the margins of his own Ramayans, including one he had personally copied from the manuscript of his guru's guru, Ramgulam. He used the title Manasi (Manas specialist) and won great fame for the brilliant ingenuity of his Katha . He was frequently called to Ramnagar to expound before the maharaja, and on one occasion, the poet Bharatendu Harishchandra is said to have presented him with two hundred gold pieces in appreciation of his Katha on the flower-garden episode. Later critics, however, have been inclined to temper their praise with criticism of some of Pathak's more far-fetched interpretations. According to Sharan, "many of his interpretations were sheer rhetorical display; he indulged in much twisting of words; yet many of his bhavs on various episodes are of the highest order and filled with the flavor of bhakti. "[76] Another author has characterized Pathak's performance style as follows:

Vandan Pathak created an entirely new style of Katha performance, which was distinct from Ramgulam's tradition. He would playfully attribute new meanings to Manas verses. Breaking apart words and compounds, he put

forward unusual interpretations which were quite new to listeners. . .. He possessed an extraordinary gift for formulating meanings and establishing correspondences [i.e., between verses]. If a novice uses this technique, the result will appear merely bizarre.[77]

Another venerable nineteenth-century expounder was Munshi Chakkanlal, a member of the Kayasth, or scribal, caste and a disciple of the great Ramgulam. Chakkanlal flourished in the latter half of the nineteenth century, contemporary with Ishvariprasad Narayan Singh, whose court he frequented and who provided him with a regular stipend to pursue his Ramayan studies. Chakkan was famed for his keen intelligence and prodigious memory, qualities that endeared him to Ramgulam. It is said that the latter came to consider Chakkan his principal "hearer" (srota ) and would not begin expounding until he had arrived, a show of preference that irritated other regular listeners. Sharan relates that once when the Katha was resumed after a lapse of some days, Ramgulam pretended to have lost his place and asked the audience to tell him where he was in the text. In the whole assembly, there was not one who could remember precisely, but when Chakkan arrived and was told the problem, he immediately gave the date on which the Katha had last been held, the episode then being expounded, and the last sequence of interpretations presented. "You see?" Ramgulam smilingly told the embarrassed crowd, "That is why I never begin without him, for even among all these listeners one cannot find a single katha-adhikari to equal him."[78]

This story underscores the notion that the principal listener at a Katha should rightfully be its adhikari —a term for one possessing "mastery" or "authority"—and again suggests the transactional nature of the performance. Listeners do not constitute merely a random and passive audience for a rhetorical display but ideally are accomplished devotees capable of receiving in its full depth and import the fruit of the expounder's intellectual and mystical discipline and of integrating it into their own devotional practice. In more secular artistic terms, an adhikari is also a connoisseur, and his presence is necessary to bring out the best in the performer. For whereas an amateur or poor expounder may hope for an audience that is ignorant of his art, the more easily to impress it with tricks and hide shortcomings, a great expounder will desire just the opposite: a group of discriminating listeners who will be adhikaris of his Katha .

Like his guru Ramgulam, Chakkanlal seems to have composed no written commentary on the Manas ; but he did train a pupil, the great adhikari of his own Katha , Ramkumar Mishra (c. 1850-1920), who came to him, it is said, when Chakkan was ninety-five years of age. A native of Bundelkhand, Ramkumar was a learned Brahman whose childhood love of the Manas was supplemented by the study of Sanskrit literature; this led him to develop a style of Katha utilizing abundant quotations from Sanskrit texts as "proofs" (praman[*] ) of Manas verses. Throughout his career, Ramkumar assembled notes (kharra ) on sheets of foolscap; Sharan remarked that the early notes, which he had seen, were heavily influenced by older written commentaries: "It is dear from them that his Katha in those days was merely based on tikas[*] ."[79] Later, Ramkumar moved to Banaras and began to attend the legendary Ramayani-satsangs organized by Maharaja Ishvariprasad in Ramnagar. It was there that he first heard Chakkanlal and decided that none other than the aged Kayasth should be his own Manas-guru . Although Ram-kumar was living and working in Banaras, he made the long and tiring journey across the Ganga to Ramnagar each evening and devoted his nights to a systematic study of the epic under Chakkan's direction. An affectionate relationship developed between the two men. Because of the pains of old age, Chakkan had become addicted to opium, and despite the old teacher's protests Ramkumar would fill his pipe and perform other menial tasks. Sitting by Chakkan's bed, he would recite from a pocket edition of the Manas and then fill its margins with notes as the teacher expounded each line in turn.

Sometimes Lala-ji [Chakkan] would become unconscious, but Ramkumar would remain seated and go on writing and pondering and wouldn't waken him. After some time, when Lala-ji opened his eyes again, he'd see him still sitting there and say in a very sweet and humble voice, "Oh, Pandit-ji, are you still here? I must have dozed off—it's old age. Very well, write . . . where were we?" Then he would resume dictating. In this way—reading, listening, writing—sometimes the whole night would pass.[80]

According to Sharan, Chakkan would often express regret that his best student had come to him only in his old age.

"Pandit-ji, have you come to study at my deathbed? If only you'd come sooner, then I could have given you a real taste of this nectar! Now I can only offer a peep into the treasurehouse." At this Ramkumar would say, "Lala-ji,

such as it is, it's more than enough. With these small jewels you've given me, I will become a millionaire! And in the future, with more effort along this same path I'll uncover still more treasure."[81]

This assessment was shared by Ramkumar's contemporaries and the later tradition, for he became unquestionably the preeminent vyas of the turn-of-the-century period. Like Vandan Pathak, he developed a new style of Katha , which influenced many later expounders—the nonsequential style now associated with urban festival performances. Ramkumar differed from most other expounders in that he performed very little—according to Sharan, for no more than one or two months out of a year. The remainder of the year was spent preparing the topic by reading, thinking, and drawing up detailed notes. Sharan describes his intense manner of working:

He always lived by himself and didn't socialize. If someone came by, he would straightaway put his sacred thread over his ear and announce that his stomach was upset and he needed to relieve himself.[82] Then the moment the visitor had departed he would plunge back into thought. When he went out to bathe or shop for necessaries he carried pencil and paper in his shirt pocket. While walking he'd always be pondering some episode or other, and if a bhav occurred to him, he'd immediately sit and write it down and only then continue on. Even while attending to the call of nature and so forth, he remained engaged in his work.[83]