Two

The Text in Recitation and Song

Whoever recites this with love,

utters, hears, or ponders it,

becomes enamored of the feet of Ram,

free of the Dark Age's stain, a sharer in auspiciousness.

1.15.10-11

The Varieties of Recitation

The recitation of Tulsidas's epic is one of the most visible—and audible—forms of religious activity in Banaras. It forms a part of the morning and evening worship of innumerable households, is broadcast by loudspeakers from the spires of many temples, and periodically, at the time of major public programs, echoes for hours each day through large sections of the city. Similarly, the singing of the text to musical modes with instrumental accompaniment is a popular evening pastime, and recently, the playing of a commercially recorded version of the sung epic has become a virtually predictable background to functions ranging from annual temple srngars[*] to family mundan[*] and marriage ceremonies.[1] In order to understand the presence and role of the Manas in these

varied activities, it is first necessary to examine some of the implications of the indigenous notion of "recitation" (path[*] ) itself.

Whereas the term puja is generally applied to the most common form of worship in popular Hinduism (the veneration of a deity with offerings of flowers, incense, and lights, accompanied by prayers or hymns of praise), the term more often used for personal worship is the compound puja-path[*] . The linking of these two terms is indicative of more than just the Hindi speaker's fondness for alliterative compounds. Path[*] is a Sanskrit word meaning "recitation, recital, reading, perusal, study, especially of sacred texts";[2] its presence in the compound reflects the importance of the oral/aural dimension of ritual and the notion that it should ideally include recitation of the sacred word. Since path[*] can refer to recitation from memory as well as to reading aloud, it is an activity in which the illiterate as well as the literate can engage.

In principle, texts for recitation can be drawn from a vast field of sacred literature, much of it in Sanskrit: the Vedas, Upanishads, epics, eighteen major and countless minor Puranas, and numerous sectarian works. Certainly there are individuals whose daily path[*] is taken from some of these works, such as the Bhagavadgita and the Valmiki Ramayana[*] . But in practice, access to Sanskrit literature is restricted to a small segment of the Hindu population, and most path[*] selections of any length tend to be taken from vernacular religious works, of which the most popular is the Manas .

Since the Manas is a narrative, the most logical way to recite it is sequentially from beginning to end. This is referred to as parayan[*]path[*] —"complete recitation"; most Manas reciters are engaged in a parayan[*] of one kind or another. But because the text is of epic proportions and the amount of time most people can devote to daily recitation is limited, it becomes necessary to divide the book into segments that can be conveniently covered in daily installments. A common approach is to read a fixed number of stanzas daily, such as five, seven, or ten. At the charitable trust known as Chini Kshetra, near Dashashvamedh Ghat in central Banaras, the Manas is chanted each morning from 8:00 to 8:30 by some thirty small boys—Brahman students who have come to the city for religious studies—who proceed at the rate of five stanzas per day. Their parayan[*] takes about seven months to complete, whereupon they begin another. Other people have told me that they recite "ten stanzas each morning and evening," "thirty-six stanzas a day," or some similar regimen. One young man, an aspiring vyas , or expounder of the

text, told me that he read the Manas for "one to two hours" every afternoon when he came home from college. When I asked how much of the text he covered during this period, he replied, "Generally only one or two lines, and never more than a stanza." Clearly, this man's path[*] was not just recitation but involved (as he further explained) a careful study of the text with the aid of a commentary. His parayan[*] , he said, would take five years to complete.[3]

Individuals may proceed through the text according to some such regimen of their own choosing, but two formalized types of recitation are currently widely practiced: navah parayan[*] , or "nine-day reading," and the thirty-day masparayan[*] . (month's reading), Most printed editions of the epic contain annotations indicating stopping points for each of these sequential readings and also include detailed instructions in their introductory matter for accompanying ritual procedures. A third form of recitation is akhand[*]path[*] , or "unbroken reading"—the recitation of the entire Manas within a twenty-four-hour period.

Although there are various systems of dividing the text for sequential recitation, those in common use today are featured in the ubiquitous Gita Press editions of the epic, and they have some notable idiosyncrasies. The system of navahparayan[*] , for example, is based on a purely mathematical division of the epic's 1,074 stanzas into daily installments of 119 or (on three of the days) 120 stanzas. But since the stanzas are of varying lengths, the length of the daily installments (and of the time required to recite them) varies accordingly, although the numerical count of the stanzas remains constant. In one nine-day program that I attended, for example, the amount of time devoted to the daily reading varied from about four to six hours.

The nine-fold division is, of course, quite independent of the epic's narrative structure. Thus, the third day of recitation concludes with the 358th stanza of Balkand[*] (120 + 119 + 119 = 358), even though only three stanzas remain in this kand[*] and so it might appear reasonable to finish it and be ready to begin Ayodhyakand[*] the following day. More important to devotees, each day's reading is dominated by a key episode in the narrative. Thus, Day One is particularly associated with the story of the marriage of Shiva and Parvati, which forms part of Tulsi's "introduction" to the Ram story and occupies about 70 of the 120 stanzas recited that day. The high points of Day Two are the birth of Ram and the first meeting of Ram and Sita in King Janak's flower garden. Day Three is dominated by the marriage of Ram and Sita, and so forth. The

importance of these narrative focal points for nine-day recitation programs will become clear when I examine several programs in detail.

A mathematical division of the text into thirty parts for masparayan[*] yields a daily installment of thirty-six stanzas; this is known as "balanced" or "even" reading (santulit path[*] ).[4] The Gita Press scheme, however, is anything but balanced—daily passages vary from as few as sixteen to as many as ninety stanzas—which is puzzling, since the system is presumably meant for the convenience of people with limited time for daily recitation. In any case, it is commonly held that undertaking a masparayan[*] requires "an hour a day."

"Unbroken" recitation is, as the name implies, uninterrupted. The specific rites and rigors of this type of path[*] are discussed below, in the context of a description of such a performance.

Spreading the Word: The Puranic Recitation Model

Although belief in the power of the oral sacred word dates back to the earliest period of Indo-Aryan culture, the notion of the social role of sacred text has changed considerably during the past two millennia. The preservation of the Vedic corpus was insured by an elaborate system of education within Brahman lineages, by the notion of the text as an efficacious mantra that could never be altered, and by the evolution of the spoken language, which fossilized and fixed the Vedic forms. The result was the extraordinary oral preservation of much of Vedic literature. But preservation and transmission need not imply propagation and dissemination. Oral performances of Vedic texts were not, apparently, fully public occasions; large segments of the population—notably, all women and Shudras—were forbidden ever to hear the sacred words. Indeed, the insistence on oral transmission in the Vedic educational system (which continued even into the period when writing had become commonplace and other religious texts were being written down) presupposed the view that texts such as the Rg[*] veda were not merely too sacred to be written down but also too powerful to be made generally available. Access to the texts had to be restricted not only to specific persons but also to persons in specific conditions—to twice-born males who had entered a ritually pure state. Thus, even though Vedic literature was an "oral tradition," it was not, within historical times, a "popular" one.

With the rise of devotional cults centered on post-Vedic divinities, the prevailing view of the accessibility of the sacred word underwent a profound change. The words of the scriptures—the newer epic and Puranic texts as well as the Vedic corpus—were still viewed as potent and efficacious. But in contrast to the generally elitist focus of the Vedic tradition, the devotional cults emphasized a relative spiritual egalitarianism and put forth the view that ultimate salvation lay within the reach of everyone, for it depended on the grace of a supreme deity—usually Vishnu, Shiva, or the Goddess—whom devotional theology placed far beyond the hierarchies of this world and whose primary relationship with humankind depended on bonds of love and compassion. Equally important, the medium through which people learned of this god was the "old story," the Purana.

The Puranas catalog the epithets and attributes of their chosen deities and detail instances of the god's compassionate intervention in cosmic affairs. They also announce—frequently and often at considerable length—their own efficacy and the many benefits to be derived from listening to, reciting, or copying them or causing others to do so. These texts emerged during the period when Brahmanic Hinduism was sustaining a severe challenge from the "heretical" sects of the Buddhists and Jains, who actively proselytized among occupational and ethnic groups deprived of status by the Brahmanical establishment. The response to this challenge involved not merely a restatement of the orthodox position but a new synthesis, which absorbed many aspects of the heterodox critique. Puranic Hinduism itself became proselytizing, and the fact that the primary media of its message of salvation were written collections of stories necessitated a new attitude toward the preservation and dissemination of text.

In the absence of printing, manuscripts had to be copied frequently in order to preserve them from the perils of the climatic cycle and from (in Anjaninandan Sharan's words) "his majesty the white ant."[5] Communicating such texts to a predominantly illiterate audience necessitated frequent public recitation, and listeners were encouraged to memorize and repeat sections of them. All of these objectives are reflected in the texts, especially in the phalsruti verses, which detail the rewards attendant on hearing, reciting, or copying a Purana.

Examples of such built-in textual promotion appear in the c. tenth-century Bhagavatapurana[*] , which became one of the most influential

Vaishnava scriptures. The mahatmya of this text—a panegyric in six chapters—details the merits to be obtained from reciting or hearing it or from presenting a copy of it to a devotee. For example, it declares,

That house in which the recitation of the Bhagavata occurs daily, becomes itself a holy place, destroying the sins of those who dwell there. He who recites daily one-half or one-quarter of a verse of the Bhagavata , secures the merit of a rajasuya and asvamedha sacrifice.[6]

But although grandiose rewards are said to attend upon even minimal involvement with the Bhagavata , the meritorious activity prescribed most often and in greatest detail is the hearing of the entire text over a period of seven days. The benefits of this procedure are emphasized repeatedly: it cancels out even such cardinal sins as the murder of a Brahman (4.13), bestows certain liberation (1.21), and is, in fact, superior to every other kind of religious activity (3.51, 52). The third chapter of the mahatmya explains the origin of this procedure as a concession to the constraints of the present Kali Yuga, or Dark Age.

Since it is [now] not possible to control the vagaries of the mind,

to observe rules of conduct,

and to dedicate oneself [for a long period], the hearing [of the Purana]

in one week is recommended.[7]

The sixth chapter of the mahatmya is devoted to instructions for undertaking a recitation program, covering such details as the selection of an auspicious date and time for the program, the preparation of the site, and the dietary restraints and other vows to be observed by reciter and listeners. Such prescriptions suggest the ritual nature of the performance, which is further revealed by the repeated identification of the program as a "seven days' sacrifice" (saptahayajna ).[8] However, although the sponsorship of this "sacrifice" is a matter of individual initiative (and the sponsor, like the Vedic patron, or yajamana , can expect to reap personal benefits from the performance), the program is to be a public rather than a private event. The instructions detail even the wording of invitations and announcements to be sent out, recommend that people attend "with their families," and specifically urge the program to be brought to the attention of women and Shudras—the very groups excluded from hearing the recitation of the Vedas.[9]

Similar instructions can be found in other Puranic texts; they serve to remind us that the Puranas, in Giorgio Bonazzoli's words, "are not

private books, but rather 'liturgical' texts. . . . They are public religious books, which are often used for specific public rituals."[10] Puranic passages prescribe recitation programs of varying lengths, but seven and nine days are the most commonly recommended durations. The former, as noted, has become standard for the Bhagavata ; the latter for its apparently later rival, the Devibhagavata , which glorifies the exploits and theology of the Goddess. Given the composite nature of the Puranas and the likelihood that they were repeatedly rewritten over the course of centuries, it is difficult to determine when such rituals came into use; Bonazzoli notes that the most detailed prescriptions appear to belong to the "most recent" strata of the texts and hence may date back no further than a "few centuries," although this does not preclude the possibility that they describe procedures already in use at an earlier period.[11]

The current systems of nine- and thirty-day recitation of the Manas seem to derive, in turn, from this Puranic tradition, though it is unclear at what point the vernacular epic acquired for its audience the kind of status that allowed such ritualized performance. Some scholars question whether either system much predates the nineteenth century and point out that instructions for systematic recitation are notably absent from older (pre-1800) manuscripts of the epic.[12] We can surmise that the recitation of the Hindi epic was conducted in the beginning along less formal lines and only gradually became ritualized.

Popular belief, however, attributes the origin of the practice of nine-day recitation to Tulsidas himself, citing a well-known legend recorded in the hagiography Mulgosaim[*]carit , which was allegedly composed seven years after Tulsi's death by one of his intimate circle, Benimadhav Das (d. 1643). The discovery of a manuscript of this work in a village in Bihar in 1926 occasioned much excitement—and also much skepticism—from literary scholars, several of whom have pronounced it a late nineteenth-century fabrication[13] Such criticisms notwithstanding, the

biography, issued in an inexpensive edition by Gita Press as early as 1934, has helped shape the popular conception of Tulsi's life. It abounds in miraculous incidents glowingly reported (i.e., Tulsi at birth possesses a full set of teeth, is the size of a five-year-old, and immediately utters the word Ram ). The miracle relevant to the present discussion is alleged to have occurred when Tulsi was en route to Delhi. The beautiful daughter of a certain nobleman was, through a deception, betrothed to a person of her own sex.[14] When the truth became known after the marriage, the families of the couple appealed to Tulsi to save them from disgrace.

They approached him; compassion filled the saint's heart.

For their sake he performed a nine-day recitation. . . .

The woman became a man when the recital was completed.

Thrilling with delight, Tulsi cried, "Victory! Victory to Sita-Ram!"[15]

Apart from asserting the origin of nine-day recitation in Tulsi's own practice, this story suggests the power that such a performance can release. This theme is echoed in other legends and highlights the fact that, as in the case of seven-day recitations of the Bhagavata , nine-day Manas recitations are usually undertaken to achieve some specific material or spiritual end.

Whereas navahparayan[*] . recitation frequently occurs in the context of public performances, the daily discipline of masparayan[*] . is more typically an individual or family activity, and its present popularity thus has two preconditions that have been met only in recent times: the existence of a significant audience of literate devotees and the ready availability of copies of the text. The current vogue for masparayan[*] thus appears to be historically related to the advent of both mass education and popular publishing in North India.[16]

A published edition of the Manas emerged as early as 1810 from Calcutta, the city in which, partly because of the presence and patronage of the College of Fort William, popular publishing in Hindi as well as Bengali had its start. The editions issued during the next five decades document a westward movement of publishing activity into the heartland of the Hindi belt, with editions appearing from Kanpur (1832), Agra (1849), Meerut (1851), and Banaras (1853). The real explosion in Manas publishing, however, occurred only after 1860; during the next two decades more than seventy editions of Tulsi's epic appeared from large and small publishing houses located in cities as widely separated as Calcutta, Bombay, Delhi, and Lahore and from numerous smaller centers in between. Notable during this period was the steadily growing size of many editions as they came to include greater amounts of front and back matter as well as line-by-line prose translations and longer commentaries on the text.[17] Some of the appended features—such as glossaries of "difficult words" and explanations of mythological allusions in the text—suggest that the audience for the Manas was growing beyond the boundaries of the epic's linguistic and cultural homeland.[18] The authors of the paraphrases and commentaries offered in these expanded editions, like the editors of the earlier generation of simpler mul editions (containing the Manas text alone), were scholars known in their home regions for their oral exposition on the epic; their reputations, as well as the influence of their interpretations, were greatly enhanced by their being featured in such widely sold editions as those of Naval Kishor Press of Lucknow and Shri Venkateshvar Steam Press of Bombay. Thus, the availability of mass-printed editions contributed not only to increasing the reading and recitation of the Manas but also to creating new patrons and audiences for the art of oral exposition.

An important development in the modern dissemination of the Manas was the founding in the early 1920s of the Gita Press in Go-

rakhpur, a small city in northeastern Uttar Pradesh. The activities of this press constitute a significant chapter in North Indian cultural history and are especially relevant to the rise of the Sanatan Dharm (Eternal Faith) movement, of which the founder and editor of the press, Hanuman Prasad Poddar, was an influential spokesman. In 1926 the press began issuing a handsomely printed monthly called Kalyan[*] (Beneficence), which was intended to present the Sanatani message to a mass audience. Each year, this journal appeared in eleven ordinary issues and one book-length special issue that focused on a chosen theme. Because the journal rapidly became a household word among pious Hindus and its issues were treasured and shared among relatives and friends, its relatively modest printing figures belie the extent of its impact.

One of Poddar's early objectives was to make available on a mass scale a "critical edition" of the Manas ; to this end Kalyan[*] issued an appeal for early manuscripts, in the hope of obtaining a complete one in Tulsi's own hand. This hope was not realized, and in the 1930s Poddar, with the help of Anjaninandan Sharan, a scholarly sadhu of Ayodhya, began to assemble an edition based on the oldest available manuscripts. The fruit of his labor—and a milestone in popular Hindi publishing—was the long-awaited Manasank (Manas special issue) of Kalyan[*] , which appeared in August 1938. More than nine hundred pages long and lavishly illustrated with specially commissioned paintings embellished with gold and protected by waxed slipsheets, it looked less like a journal than like a family heirloom—and such it became for thousands of North Indian families. It contained the complete Manas text accompanied by Poddar's verse-by-verse prose translation, as well as extensive front and back matter. It had an enormous (by Indian standards) first printing of 40,600 copies and became the basis for the many editions subsequently issued by Gita Press—which range from tiny "pocket" (gutka[*] ) versions containing only the basic text to huge folio-size volumes with commentary, appendixes, and illustrations. The popularity of these editions, which are seen all over North India today, may be gauged from the example of the pocket version, which by late 1983 had gone through seventy-two printings for a total issue of 5,695,000 copies, with two printings of 100,000 copies each in 1983 alone.[19]

The advent of modern-language publishing was a phenomenon with

profound consequences. The expensive and time-consuming process of manuscript copying was rendered obsolete, and literature suddenly came into the hands of both the urban and the rural middle classes. This development meant that all literate persons acquired the potential for a kind of participation in sacred literature that had formerly been the domain of a specialist elite. Books could be read, of course, for private enjoyment and edification, but sacred books could now also be recited by nonspecialists. The meritorious activity of path[*] , rooted in the immemorial belief in the potency of the recited sacred word and encouraged by the Puranic tradition, was now facilitated by the ready availability of revered texts.

When people acquire the ability to read, what do they choose to read? The observations of nineteenth-century British scholars and administrators confirm that, by their time at least, the Manas had become established in North India as the religious text and cultural epic par excellence and had come to permeate and influence Hindu society as its very archetype of literature: its Book. Growse reported that the epic, "is in every one's hands, from the court to the cottage, and is read, or heard, and appreciated alike by every class of the Hindu community, whether high or low, rich or poor, young or old."[20] And while their Indologist colleagues devoted themselves to the study of the Sanskrit classics, British administrators and missionaries, out of expedience, studied the Manas . Grierson was to recall:

Half a century ago, an old missionary said to me that no one could hope to understand the natives of Upper India till he had mastered every line that Tulasi Das had written. I have since learned to know how right he was. . . . Pundits may speak of the Vedas and Upanishads, and a few may even study them . . . but for the great majority of the people of Hindustan, learned and unlearned, the Ramayana[*] of Tulasi Das is the only standard of moral conduct.[21]

Vibhuti Narayan Singh, present maharaja of Banaras and heir to a family that has patronized the Manas for more than two centuries, told me that among the nineteenth-century aristocratic and landowning families of eastern Uttar Pradesh, the ability to read the epic was virtually the criterion of literacy: "When they were considering a girl's qualifications prior to marriage, then the question would come up as to whether

she could read. If she was literate, then they would say proudly, 'Of course, she reads the Manas .'"[22] His younger brother recalled the role the epic played in their own education—as the means by which their mother taught them the alphabet: "She would form letters for us out of snippets of paper—a line, a circle, a hook shape—to make the various characters ka, kha , and so forth. Then she would say, 'Now go look in the Ramayan and find one like this,' and we would find a caupai that had that letter. Then Mother would recite that to us. In this way we learned our whole alphabet from the Manas ."[23]

Before leaving the subject of the various systems of path[*] and their origins, something must be said about the numerical divisions used. Why seven days to read the Bhagavatapurana[*] and nine or thirty for the Manas ? Clearly all three numbers are expressions of completeness or totality, corresponding to basic divisions of time and space in the Hindu worldview. Seven not only represents a full week (called "a seven"—saptaha —in Sanskrit) but is also used to express many kinds of completeness—the seven oceans, seven divisions of the world, seven mystical steps to heaven, and so forth. Similarly, thirty days—one lunar month—represents a complete unit of "light" and "dark" fortnights. This paradigmatic light/dark dualism gives rise to a variety of religious associations; for example, the worship of celestial deities is performed during the bright half of a month (suklapaksa[*] ), whereas the dark fortnight (krsna[*]paksa[*] ) is more suited to the worship of autochthonous fertility deities and the souls of departed ancestors. Each lunar cycle is also a microcosm of the greater cycle of the year, which is similarly divided into "light" (devayan ) and "dark" (pitryan[*] ) halves.[24]

Because they encompass such fundamental dualities, the lunar months of the Hindu calendar are complete units of time in a ritual sense, as the "profane" (for Hindus) months of the Christian calendar—used for government and business purposes—can never be. To undertake a parayan[*] —a ritual "completion"—of a sacred text within such a time span is to achieve a kind of heightened completeness. Of course, devotees do not necessarily time their recitations to correspond to calendar months. More commonly, they choose an auspicious date to begin their reading—often a date associated with an incident in the story, such as the fifth of the bright half of Margshirsha (November/December), the

traditional wedding anniversary of Ram and Sita. Dating systems have been published for the epic, which match a specific lunar date to virtually every incident in the narrative.[25] Besides satisfying the scholasticism of Ramayanis—traditional epic specialists—such systems provide devotees with an enhanced sense of identification with the characters and incidents of the text and permit them to select auspicious days for their own undertakings based on its archetypal chronology.

Even though the number nine does not correspond to any basic calendrical unit, it too represents a cosmological totality, its prime association being with the nine planets (nav grah : i.e., the sun, moon, the five planets known to ancient Indian astronomy, and the asterisms Rahu and Ketu). It is used in other contexts to connote completeness, as in the "nine portals" of the body and the "nine precious gems" found in the earth.[26] But whereas the number nine has cosmological significance, it does not appear to have the same positive connotations as the number seven; the nine planets are each characterized by specific attributes, and two of them, Mangal and Shani (Mars and Saturn), are predominantly malevolent while two others, Rahu and Ketu, are demons associated with dangerous cosmic phenomena—eclipses of the sun and moon. These are cosmic entities from which one seeks protection—for example, by wearing rings and bracelets containing the metal or gem associated with the dangerous planet or by worshiping powerful protective deities (as in the modern worship of Hanuman on Tuesday and Saturday).

Although nine-day recitation appears to have become merely a formalized standard for the Manas , its adoption may be rooted in the popular conception of Ram as a beneficent and protective hero. As already noted, nine-day recitations of the Manas are usually associated with a specific objective such as gaining a boon or averting danger (e.g., Tulsi's legendary use of the ceremony to save a family's honor). A modern pamphlet on the ritual uses of the Manas includes an account of a navah

performed by a sadhu in order to save the life of a critically ill (and unbelieving) English boy.[27] One of my Banarsi acquaintances, an enthusiast for the thirty-day recitation of the epic, mentioned two occasions on which she had undertaken navahparayan[*] : each was an emergency involving the serious illness or injury of a close family member. The successful outcome of both crises had, she said, greatly deepened her faith in the power of the text. The persistent associations of the Ramayan with protection and succor may be reflected in its ritualized recitation over a period associated numerologically with powerful and dangerous cosmic forces.

A second observation about the number nine likewise concerns the calendar and the appeasement of dangerous divine beings, in this case the mother goddesses, whose mythology reflects a paradoxical relationship between fertility/nurture and destructiveness. The two most important festivals for the worship of these goddesses occur over periods of nine days—or rather, "nine nights" (navratra ); both fall in the bright halves of months and have important associations with the Ramayan story. The Navratra festival in Chaitra (March/April) climaxes on the ninth lunar day of the bright half of the month, which is also the birthday of Ram (Ram Navami). Its counterpart in the month of Ashvin (sometimes called mahanavratra , or "great nine-nights") is immediately followed by the "victorious tenth" (Vijaydashami), which commemorates the goddess Durga's slaying of the buffalo-demon and is also the festival of Dashahra, celebrating Ram's defeat of Ravana. This conjunction of festivals is seen as no coincidence, for it is commonly believed that Ram himself worshiped the goddess for nine nights to obtain the power (sakti ) necessary to slay his demon foe. Moreover, his awakening of this destructive power during the month of Ashvin is held to have been "untimely" (akalbodhan ) and hence to have required special protective measures.

In this connection, it is noteworthy that the first printing of the Gita

Press pocket edition of the Manas was specifically for an "All-India" parayan[*] recitation during the Chaitra Navratra observances in 1939, a performance that had been promoted for months in the pages of Kalyan[*] .[28] The encouragement by the journal's publishers of mass reading of the Manas during the "nine nights" of goddess worship again suggests the role of the epic as a synthesizing element in North Indian religion, specifically as a mediator between the traditions of Vaishnava devotionalism and Shaiva/Shakta worship. Both as a cultural epic and as the most accessible religious text of the region, the Manas becomes the text of choice for filling any vacuum in popular religious practice. Since the "nine nights" are explicitly devoted to worshiping the mother goddesses, one might expect to hear a recitation of the Devibhagavatapurana[*] , which indeed has a history of association with this festival.[29] But since this text is in Sanskrit, it is not suitable for mass recitation. Now that a need is perceived for a mass path[*] to complement the puja conducted over the nine nights, the Manas is enlisted to fill the void.

In my fieldwork, I found a similar line of reasoning used to explain the sponsorship of Manas recitation programs by Devi temples in the Banaras area, such as Kamaksha Devi in the neighborhood known as Kamacha, a shrine revered as a localized manifestation of the famous tantric center at Kamrup in Assam. A nine-day recitation and exposition festival is sponsored by this temple annually during the month of Paush; in structure, it is a scaled-down version of some of the large navah programs described later in this chapter. When I questioned a devotee of the temple as to why a text dealing specifically with the Goddess was not selected for performance in this setting, I was told, "Yes, of course they could recite the Devibhagavata or some other Purana, but in that case, few people would come to the program. So they choose the Manas , because it appeals to everyone—rich and poor, literate and illiterate—and is sure to bring in a crowd."[30] If the Manas is the best choice for logistic/promotional reasons, its use can be justified equally easily on theological grounds. A college student remarked to me in connection with the same program, "In the Manas is found the story of the marriage of Shiva and Bhavani, and so many other stories. So we feel that in it all the deities are honored, and it can be recited in praise of any of them."[31]

In this example, as indeed in the whole phenomenon of nine-day recitation, we see the Manas both conforming to the model of the Puranas and eclipsing them as the preeminent text for public performance.

The Rites of Recitation

The preceding chapter introduced two basic criteria for regarding a verbal act as a performance: criteria termed "formal" and "affective." In performances where ritual is important, the formal criterion often reflects culture-specific notions of personal purity and of sacred space and time. Formal elements in ritual help to achieve the affective purpose of the performance—for example, the "sense of peace" that devotees say they derive from reading the Manas or even the miraculous benefits that they believe can result from certain types of recitation.

Bathing is an essential preliminary to nearly all Hindu ritual, and few people would dream of opening, much less reading, their Ramayan without first having bathed and put on clean clothes. In Banaras, the daily routine for many people begins with a sunrise bath in the Ganga followed by a round of visits to favorite temples. Morning Ramayan path[*] is often incorporated into the latter activity and carried out within a temple, especially one dedicated to Sita-Ram or Hanuman.

Considerations of space are also important; many regular reciters favor a special seating mat (asan ) made of kus , a grass believed to have auspicious qualities, which has figured in rituals since Vedic times. The early morning equipage of the devout Banarsi may be considerable, what with a set of fresh clothes, a rolled-up mat for puja-path[*] , a brass pot for Ganga water, a basket of flowers and vermilion powder, and a toilet kit for grooming and for applying a mark (tilak ) to the forehead. Once the asan has been spread, other items may be unpacked: small framed pictures of deities or even tiny statues installed on portable shrine stands, an incense burner and an oil lamp for ceremonial worship, pamphlet versions of hymns and invocations, and of course, the Book itself. Most devotees honor and protect the Manas by keeping it in a neatly sized bag made of ocher or crimson cloth. Others wrap it in an ocher shawl block-printed with Ram's name (Ram-namdupata[*] ). As a preliminary to path[*] , the book may be placed on a wooden stand and worshiped with flowers and incense. The ritual typically includes an invocation of Ganesh, the "remover of obstacles," and of Hanuman, the special patron of the Ramayan—the Hanumancalisa is the most popular text for this purpose.

The melodies to which the epic is chanted include several common ones in wide use today, as well as numerous regional and local—and countless individual—variations. In my fieldwork I was struck by the variety of melodies and singing styles used by devotees in their impromptu recitations. The distinctiveness of a given style would sometimes be noted with pride, as by the man who sang to me during a ferry ride across the Ganga, saying, "In my place in Bihar we don't sing the Ramayan like they do here; we have our own way" and then launching enthusiastically into a passage from Balkand[*] . Katha programs also afford opportunities to hear varied styles of chanting, since each expounder typically has a preferred melody to which he or she intones all quotations from the epic.

In Banaras, two melodies dominate Manas performances. One is used in most of the local Ramlilas and is commonly called lilavani[*] (the "voice" or "melody" of lila ). The Ramayanis who sing at the Ramnagar Ramlila say that this is the melody to which the epic is sung by the divine sage Narad. They contrast it to what they call Tulsivani[*] , the melody used for most public recitation outside lila performances. In Ayodhya, some 150 kilometers northwest of Banaras, I found other melodies in use; one was identified to me simply as Avadh dhun —"the style of singing [dhun ] of Avadh [Ayodhya]."

Anyone who has spent time in Banaras in recent years can hardly have escaped hearing Tulsivani[*] Given the frequency and (with amplification) audibility of Manas recitation programs, it forms a regular and unmistakable motif in the daily urban cacophony, and thanks to twenty-four-hour programs, it often echoes eerily through deserted bazaars and lanes during the midnight hours. Compared to lila -style chanting, which is strident and stylized and requires the antiphonal alternation of two groups of singers, Tulsivani[*] is simpler and more lilting, does not alter the text, and may be rendered by a single performer. It is, so to speak, more "recitative." It appears to have become the standard melody for major public performances, and I heard it not only in the Banaras area but also in Ayodhya and New Delhi.

The Samput[*]

The most distinctive formal feature of all forms of parayan[*] citation is the insertion, after each stanza, of a refrain that serves as an invocation or benediction. This is known as a samput[*] terally, a "wrapper"—and indeed it serves as an enclosure or frame for each unit of recitation.

Just as Tulsivani[*] now dominates public recitation, so a single samput[*] has gained wide acceptance. Taken from Book One, it is a supplication to Ram in his child-form, uttered by Shiva as he commences his narration to Parvati:

mangalabhavan amangala[*]hari | dravahu so Dasaratha ajira vihari ||

Abode of auspiciousness, remover of inauspiciousness,

may He who plays in Dashrath's courtyard be merciful!

1.112.4

The chanting of the samput[*] is considered essential to the successful completion of a ritual recitation. In performances in which I participated, one of the reciters would occasionally neglect to include the refrain after a stanza; other participants would immediately stop the recitation and correct this mistake. Clearly the samput[*] is (in Bauman's terms) one of the formal "keys" by which a reciter "assumes responsibility" for an act of Manas recitation-as-performance.[32]

Although most public performances use the samput[*] given above, reciters sometimes prefer other refrains. At the Kanak Bhavan Temple in Ayodhya, a nine-day program is held at the time of Ram's birthday each year under the direction of the temple's resident Ramayani, Ramsahay Surdas.[33] Blind from birth, Ramsahay has committed the entire Manas to memory, and his chosen samput[*] —a line spoken by King Manu when his penance is rewarded with a vision of Ram's transcendent form—seems touchingly appropriate for a blind singer in the bhakti tradition.

Lord, having seen your lovely feet,

now all my desires are fulfilled.

1.149.2

When recitation is undertaken to achieve some desired end, the choice of samput[*] depends on the goal of the ritual, for it is well known that certain refrains can produce such desired effects as the cure of an illness, the birth of a son, or success in obtaining a job. The specialized uses of the epic are prescribed in the front matter of popular editions or in separate manuals sold in religious bookstalls. The special Manas issue of Kalyan[*] , for example, includes a section on ritual uses aimed at securing both "supreme" or "spiritual" (paramarthik ) and "worldly" (laukik ) goals; the latter, incidentally, outnumber the former by nearly three to one. Most of these procedures involve the use of special refrains,

appropriately chosen from among the thousands of possibilities offered by the text. Thus, a devotee craving jnan , or spiritual wisdom, should conclude each stanza of his recital with the line

Earth, water, fire, wind, and atmosphere—

the body, composed of these five elements, is utterly base.[34] 4.11.4

The significance of this line lies in more than just the familiar pañcatva (five-fold nature) doctrine it expresses, for the devotee would be aware (or would become aware in the course of the recitation) that these words, spoken by Ram to the grieving widow of the monkey-king Vail, "gave [her] jnan and removed delusion [maya ]" (4.11.3). Similarly, a person seeking "detachment from the illusory world and love for the Lord's feet" is directed to use as a samput[*] the concluding couplet of Ayodhyakand[*] :

The discipline of Bharat's conduct—

Tulsi says, whoever sings and hears of this

surely gains love for the feet of Sita and Ram

and indifference to the pleasures of this world.

2.325

The "worldly" applications of Manas recitation detailed in the same text range from such general objectives as the "removal of sorrow" to more specific ends: matrimony, the begetting of a son, even the production of rain. The effects of poison can be negated by a recitation using the following samput[*] :

The power of the name is well known to Shiva;

[through it] the searing venom became as nectar to him.[35] 1.19.7

For the much-desired boon of a son, a variant procedure is prescribed. The devotee is to commence a complete recitation from the 189th stanza of Balkand[*] , beginning,

Once, King Dashrath, reflecting inwardly,

"I have no son," became sorrowful.

1.189.2

The reciter should then proceed to the end of the story, recommence it,

and conclude with the line immediately preceding the above half-caupai . In this ritual one might say that the entire epic is used as a samput[*] to frame the cherished wish of the devotee.

The Arti

If special observances mark the beginning of a systematic recitation and a ritual frame encloses each of its constituent units, some symbolic act would seem equally necessary to mark its end. The usual concluding event in devotional worship is the arti ceremony, in which the deity is offered lights, incense, and other gifts while a devotional hymn (itself called an arti ) is sung. Popular editions of the Manas include a standardized arti written not to Ram but to the Manas itself, and this is normally sung at the conclusion of each installment in a path[*] . Like Tulsi's own narrative frames, its lyrics depart from the story in order to emphasize its eternal retelling; they cite each of the epic's divine narrators, placing Tulsidas himself in the position of honor. An opening refrain is repeated at the conclusion of each verse.

(refrain:) [We sing] the arti of the holy Ramayan,

which tells the lovely fame of Sita's lord.

Sung by Brahma and many others, by the sage Narad,

by Valmiki, learned in holy wisdom,

by Shuka, Sanak and his brothers, by Shesh and Sharada,

the fame of which is narrated by the Son of the Wind.

Sung by the Vedas and the eighteen Puranas,

containing the essence of the sastras and all holy books,

a treasure to sages; to good people, their all-in-all,

the quintessence of truth, with which all are in accord.

Eternally sung by Shambhu and Bhavani,

by the profound sage Agastya,

recounted. by Vyas and all the great poets,

dear as life to Kak Bhushundi and Garuda.

Removing the Kali Age's stain, dulling the taste of material things,

the lovely adornment of the Lady Liberation,

the herb of immortality destroying worldly afflictions,

father, mother, and in all ways, all to Tulsi![36]

Practitioners Of Mas Parayan[*]

The thirty-day recitation of the Manas is typically an individual activity; unlike other forms of recitation to be discussed shortly, it does not involve the services of professional reciters. It usually takes place in the morning as part of the devotee's daily puja-path[*] , conducted either at home or in a favorite temple. Each neighborhood Hanuman temple has its regular clientele; the most devoted reciters are apt to be older men and women who have leisure to spare for devotional activities. They are usually educated, middle-class householders with grown children, who have entered the third phase in the classic Hindu scheme of life: a vanaprastha that involves not physical departure for the forest but rather a psychological withdrawal from worldly activities and a dedication of more time to religious aims. Such people represent an important category of participants in Manas- related activities, for which they have both the time and inclination; devoting their mornings to recitation, they spend their afternoons in attendance at Katha programs, listening to expounders narrate the epic.

But lest I give the impression that Manas recitation is popular only among the elderly, I would cite the example of Rita, a young Banarsi woman. The youngest daughter of a prosperous business family, Rita had steadfastly pursued an advanced degree, worked as a teacher, and resisted her elder brother's efforts to "marry her off" (indeed, she once remarked acidly to my wife, "Here, when you get married, your life is finished"). She was approaching the age of thirty, and her brother, who despaired of ever finding a match for her, could only shake his head ruefully and remark upon "the problem with too much education for the ladies." This woman's closest friend was another unmarried woman of similarly "liberated" views and a life-style—including her own motor-bike and pilot's license—unusual for her provincial city.

Given that the Manas is not celebrated, these days, for its liberated views on the role of women,[37] it had not occurred to me that either of these young women might be an avid reader of the epic. In fact, they both were. During a nine-day recitation at a popular Hanuman temple, I was surprised to find the two of them in daily attendance with well-worn pocket editions in hand. In a subsequent interview, Rita told me that she had acquired the habit of daily path[*] from her parents, who were lifelong Ramayan devotees. As a child, she had recited simple texts like the Hanumancalisa , but as she grew older her love for the Manas stead-

ily increased, to the point that she was now nearly always engaged in one or another kind of parayan[*] and could state that "such mental peace as one gets from Ramayan path[*] cannot be gained from any other book."

Although this woman's conventional reverence for the Manas seemed to present a contrast to her independent attitudes on other matters, her remarks suggested that she regarded her personal involvement with the text as itself contributing to her feeling of independence. Thus, when I asked if she felt any special devotion toward the highly revered Ramanandi leader who had sponsored the nine-day program she attended, she brushed aside the question: "I myself do so much puja-path[*] , what need do I have of any guru?" Similarly, when asked who among modern expounders of the Manas she considered noteworthy (a question that usually elicited from devotees a ranked list of personal favorites), she forthrightly remarked that, since she herself was constantly reading the Manas , she saw no need to listen to other people's views on it, adding, "My mother respects these people, but I don't bother with them." Her greatest encouragement in Manas recitation, she said, had come not from her family but from her female friend, who was likewise devoted to the text; she mentioned several other young women in the neighborhood who also recited the epic regularly.[38] For these women, as for many other private reciters, the Manas and the structured discipline of parayan[*] recitation provides a highly valued means of personal access to the transforming power of the sacred word. Paradoxically, the affirmation of faith in the cultural epic can even foster, as in Rita's case, a feeling of personal independence from the authority structures of joint family and organized religion—the very structures that the epic is often seen as upholding.

Manas As Marathon

Like thirty-day recitation, akhand[*]path[*] —the recitation of the Manas within a twenty-four-hour period—tends to be an individual or family activity, although public programs sponsored by temples, ashrams, or civic organizations occasionally take place in Banaras, and even family programs may involve the services of paid reciters. The most important point about this kind of recitation is that it be "unbroken" (akhand[*] ). Given the scale of the epic, such a performance is necessarily a tour de force requiring the kind of dedication and stamina usually reserved, in the contemporary West, for endurance sporting events. Indeed, even though such a reading is normally understood to require twenty-four

hours, there is nothing (apart from human frailty) to prevent its accomplishment within a shorter period—one woman proudly told me that she had completed a recitation in eighteen hours; moreover, she knew someone who had done it in sixteen. Given such Olympian dedication to speed, one will understand that little attention can be paid to the niceties of diction and comprehension, and the recitation at times seems little more than a blur of sound interrupted periodically by a recognizable samput[*] .

One motive for undertaking such a path[*] is to obtain greater familiarity with the text, and several Ramayanis told me that they had performed many of these recitations as part of their effort to commit the epic to memory—this knowledge being an essential qualification for a professional expounder. Rameshvar Prasad Tripathi, an elderly expounder of Allahabad, told me that during one period of his youth he had undertaken the discipline of reciting the entire epic daily, gradually gaining speed until he was able to complete the whole of it in eleven hours (the record among my interviewees!).[39] Such a rapid-fire rendition of a religious text—and judging from my experience of twenty-four-hour performances, I would have to suppose that an eleven-hour rendering of the Manas might sound more like the buzzing of bees than the words of Tulsidas[40] —is not, in the Hindu context, viewed as peremptory or disrespectful, since the text, as a mantra, is understood to be inherently potent and efficacious, regardless of the speed at which it is recited. Further, to appreciate or understand the text means first of all to "know" it, and this in turn implies having it "situated in the throat" (kanthasth[*] —the Hindi idiom for "memorized"). To this end constant repetition, however rapid and mechanical, is regarded as a valuable means.

A Family Celebrates Divali

My first exposure to twenty-four-hour path[*] came soon after I had set-tied into a flat in a middle-class neighborhood in the southern part of Banaras. While walking to the corner shop one morning, I heard the unmistakable strains of Tulsivani[*] wafting from a side street and followed the sound to a modest one-story house set in a small garden. It was the home of Mr. Sharma, a retired Banaras Hindu University ad-

ministrator, who told me that the path[*] was an annual affair organized by his family on the eve of Divali, the Festival of Lights, which falls on the moonless night of the month of Karttik (October/November): "My son comes from Delhi for the holidays, and he and his friends arrange it." Sharma invited me to join in at any time and added that I must be sure to come the following morning for the conclusion of the ceremony, when there would be a big crowd and also a distribution of sweets.

While the Sharmas' path[*] was primarily a family affair, it was hardly a private one. There was the obligatory loudspeaker, rented from a local caterer and mounted on a corner of the roof to announce to the neighborhood that a Manas recitation was in progress. Inside, the front sitting room had been cleared of its modest furniture. The stone floor was spread with cotton carpets covered by white sheets, and a ghee-fed lamp burned brightly before a shrine alcove. In the center of the room was a low, cloth-covered table on which stood a microphone, some flowers and incense, and numerous well-worn copies of the Gita Press edition of the Manas . There was a holiday atmosphere in the house, as relatives, friends, and neighbors came and went throughout the day. The visitors would sit for a while listening to the recitation or, if they wished, take up a copy of the text and join in. A minimum of two hired reciters—priests from a nearby Hanuman temple—were always chanting; they were sometimes joined by others. The priests, who would receive a modest payment at the end of the ceremony, were expected to see that all ritual aspects of the path[*] were carried out properly.

My most vivid memory of this particular path[*] is of its midnight shift, to which I returned after spending the evening with my family. At first I thought that the program had been halted, for no sound of amplified chanting echoed through Sharma's lane and I had difficulty, in the pitch dark, locating the proper house. The silence, it turned out, was due to the loudspeaker's having been shut off at 10:00 P.M. , a remarkable and (in my experience) unparalleled act of consideration for the neighbor-hood—as the sleep requirements of nonparticipants are not normally taken into account by the organizers of Banarsi religious events. The interior of the house presented a contrast to the morning's scene of bustling activity. Several cotton mattresses had been added to the nearly empty front room, and a few young people were sleeping on them. At the central table, the hired reciters were still seated on either side of the now-extinguished microphone, working their way sleepily through the latter part of Book Three. At about midnight there were sounds of stirring in the next room, and four young people—two boys and two

girls—emerged. Four more copies of the Manas were quickly passed around and the new arrivals joined in. At about 1:00 A.M. one of the priests left off reciting, crawled over to a nearby mattress, and woke another youth, who immediately sat up, yawned once or twice, quickly positioned himself at the table, and began to recite; the other replaced him on the mattress, pulled a sheet over himself, and (to judge from the snoring sounds that almost immediately emerged from the sheet) fell asleep. An hour or so later Mr. Sharma himself appeared, beaming and looking refreshed, and took up a position at the table. Thus, the relay continued through the night.

The twenty-four-hour performance was completed on schedule at about 8:30 the following morning, after a pell-mell chase through Uttar kand[*] that slowed down only for the final verses of the epic, which were intoned with a certain solemnity, perhaps as a signal to members of the household that the great task was coming to an end. Upon the completion of the final benedictory sloka , the chanters launched into namsahkirtan —the singing of the name of Ram to harmonium accompaniment. This continued for more than an hour, while the room gradually filled with family members and neighbors. The ladies of the household appeared with brass platters heaped with fruits and sweets, and Mr. Sharma garlanded the numerous images in the family shrine. By 10:00 A.M. the room was packed with people. Incense and a small brass oil lamp were lit, all the copies of the Manas were stacked together on the central table, and a daub of vermilion was applied to the topmost volume. Everyone rose to sing the usual arti while one of the priests waved the flickering lamp before the books. The hymn concluded with shouts of "Raja Ramcandra-ji ki jay!" (Victory to King Ramchandra!), followed by the distribution of prasad .

Afterward, most of the male guests remained in the front room, chatting and munching their sweets, but the ladies quickly disappeared into the inner courtyard. A few minutes later the sound of a double-headed drum and finger cymbals could be heard, joined by female voices singing and laughing. I quickly gathered from the broad smiles on the men's faces that the songs contained galiyam[*] —ribald and abusive terms, usually dealing with joint-family relationships—such as are sung at North Indian marriage celebrations. The whole atmosphere became light-hearted as the infectious gaiety of the singing women in the courtyard was caught even by the men in the front room. The music seemed a joyous release of pent-up energy and a female response to the male-dominated solemnity of the twenty-four-hour path[*] (although women

had also, at times, joined in the recitation); the offering of such a thematic counterweight on ceremonial occasions is one of the characteristic roles of women's folksongs in North India.[41] When I asked Sharma about the singing, he remarked good-naturedly that, in his family, the path[*] was not considered really complete until the women's songs were sung.

Path[*] as Protection/Propitiation

Another unbroken recitation in my neighborhood was held to mark the birth anniversary of the eldest son of one of four brothers in a prosperous joint household. The path[*] , which began at 10:00 A.M. on the morning before the birthday, was conducted almost entirely by hired reciters, and family members showed little interest in the progress of the recitation. The performance concluded the following morning with a Vedic fire ceremony (havan ) conducted by another hired specialist, with the father of the boy whose birth was being celebrated serving as yajamana , spooning oblations of ghee and rice into a fire kindled in a metal receptacle in the living room. This was followed by the usual Ramayan arti and the distribution of prasad , whereupon each reciter was given twenty-one rupees and a cotton shawl. After the Brahmans were dismissed, the living room was rearranged in preparation for a Western-style birthday party complete with balloons, gifts, and refreshments for invited guests, including many business associates of the boy's father.

Although the parents stated only that they were conducting the path[*] to observe the birthday of their son, I noted that no such ceremony was held to mark the birthdays of the other sons in the family. Eventually I learned that prior to the birth of this boy, two children of the couple had died in infancy. The third pregnancy had naturally been an occasion of much anxiety, and although the whole subject was now avoided by family members, it appeared that the annual ceremony was a reflection of this stressful episode in family history. To have merely "celebrated" the birthday in modern style, without some gesture in the direction of larger powers, would have been unacceptable, and so a sponsored akhand[*]path[*] with all the trimmings—loudspeakers, priests, and a high-class Vedic finale—was the most appropriate way for people of their status and level of education to mark the occasion.

Such ceremonies provide another illustration of the prestige of the Manas and its adaptability to the needs of popular religious practice. They offer educated, middle-class families an opportunity to engage in socially sanctioned, merit-bestowing religious activities that require a minimum of personal involvement and to give patronage to Brahmans, who are of course happy to offer such prepackaged programs. This is not to suggest, however, that the sponsors of such programs lack a personal involvement with the Manas ; the sponsor of the program just described was actually a devoted reader of the epic. Nor does the fact that sponsors hire outsiders to recite the text and themselves refrain from participation in all but the most obligatory parts of the ritual indicate a disregard for the Manas . The mechanical recitation of sacred scripture on hire is one of the things that Brahmans are supposed to do, and the act, it is thought, automatically diffuses benefit to all, just as the jasmine creeper diffuses scent regardless of whether one takes any special notice of it.

There is another reason for the choice of professionals for such recitations: akhand[*] path[*] is not something that one sponsors simply because one likes the Manas —there are simpler and more enjoyable ways to read the epic. Unbroken recitations are rituals aimed at procuring results. The more potent the ritual, the more onerous the "assumption of responsibility" for its correct performance, and the more hazardous the risk of error. What was true of Vedic sacrifices is also true of Vedicized Manas recitation: both become the domain of specialists who increasingly assume custodianship not merely of the ritual but also of the text.

The sponsorship of an akhand[*]path[*] bestows not merely blessings but also prestige, especially if the sponsor can afford the conspicuous trimmings common to these events. The ceremony places the sponsor in a patronage relationship with local priests: a new variation on the traditional jajman reciprocity;[42] the orientation of the ritual around the Hindi cultural epic makes the ceremony more comprehensible and accessible to patrons. The implications of the popular view of the Manas as "Hindi Veda" are discussed in the concluding chapter, but we can already recognize the Veda-like role of the text in important household observances. Its corresponding role in great public ceremonies—an-other domain of ritual specialists—is taken up in the next section.

The "Great Sacrifice" of MANAS Recitation

Some three weeks after the conclusion of most of the annual Ramlila cycles in Banaras, there is another major public spectacle centered on a performance of the Ramcaritmanas . The venue of this program is the area known as Gyan Vapi, an L-shaped plaza located near the Vishvanath Temple, the city's most celebrated shrine.[43] The area takes its name from a sacred well located in one corner of the grounds, the water of which is drunk by pilgrims as a form of prasad from Shiva. The adjacent plaza is one of the few large public spaces remaining in the congested heart of Banaras; most of the surrounding area consists of a dense concentration of houses and narrow lanes, the latter usually crowded with pilgrims en route to or from the temple. At Gyan Vapi there is room to breathe, to relax in the shade of an ancient pipal tree (also sacred to Shiva and itself an object of veneration) growing near the well platform, and to recover from the pushing and shoving that, these days, is often an inescapable part of a visit to Baba Vishvanath. But the existence of this open space is significant in other respects as well. All Banarsis know that, although Vishvanath has been the patron deity of Kashi since time immemorial, his present temple is not especially old and is not in its original location. The shrine was destroyed in 1669 by order of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb and a mosque built in its stead.[44] The present-day plaza is bordered on two sides by this mosque, which is elevated on a high plinth—actually the ruined foundation of the old temple, carved traces of which remain visible beneath the austere white walls of the mosque compound. The whole Gyan Vapi complex including plaza, mosque, well, and relocated temple, has come to represent, for Hindus, a controversial and disputed memorial to the perceived atrocities of Muslim rule, and for Banaras authorities, a source of potential communal trouble.[45] Thus, by virtue of its size, location, and emotional associations, the Gyan Vapi area is an appropriate site for the staging of large-scale Hindu religious performances. Among the best-

known of these is one that begins each year on the seventh of the bright half of Karttik (October/November), when a mercantile organization known as the Marwari Seva Sangh (Marwari Charitable Society) sponsors its annual SriRamcaritmanas navahpath[*] mahayajna —a "great sacrifice of nine-day recitation" of the Manas .[46]

The commencement of the program is heralded by handbills and a large banner displayed on the main road between Godowliya and Chowk. They give the timings for daily recitation (mornings from 7:00 to 11:00 A.M. ) and for expositions on the epic by "renowned scholars" (evenings from 7:00 to 11:00 P.M. ). Meanwhile, workmen transform the dusty plaza into a festive enclosure by erecting a huge multicolored canopy (mandap[*] ), its bamboo posts festooned with chains of marigolds and auspicious asok leaves. At its southeastern corner they erect a dais, on which they arrange an elaborate tableau of life-size images of Ramayan characters. These are made of unfired clay sculpted over a framework of wood and straw, brightly painted and adorned with appropriate costumes, jewelry, and weapons. These temporary "likenesses" (pratima ), consecrated by a priest with the prescribed life-giving prayers, become as suitable for worship as more permanent images of stone or metal, even though they will only be worshiped for a fixed period and will then be desanctified and consigned to water. In Banaras such images are produced for a number of festivals, most notably for Durga Puja, which is lavishly celebrated by the city's Bengali population. Durga images are displayed in elaborate tableaux depicting the Goddess, adored by a host of subsidiary deities, in the act of slaying the buffalo-demon, Mahishasur. Since the Manas recitation festival at Gyan Vapi is of recent origin, it is likely that its use of a tableau reflects the influence of the Durga Puja observances.

The tableau offers a representation, immediately familiar from religious posters and calendars, of the culminating scene in the Ramayan story as recounted in the Manas , in which the victorious Ram is enthroned beneath a royal umbrella with Sita at his side, flanked by his three brothers, by Hanuman, and by his family guru, Vasishtha. Throughout the nine days of the festival, this tableau will be attended by a priest. It will receive the worship and offerings of devotees and will be the focus of arti ceremonies at regular intervals. At the conclusion of the program, the images will be taken in procession to Dashashvamedha Ghat for their "dismissal" (visarjan ) in the waters of the Ganga. To the

Figure 6.

Copies of the epic rest on a harmonium during a break in a public

recitation program

right of the tableau is a raised seat spread with golden cloths; this is the vyaspith[*] , or "seat" of the Ramayan expert who will serve as master reciter and also of the invited scholars who will discourse during evening sessions. Before it is a wooden stand likewise covered with glittering cloths, upon which rests an enormous copy of the Manas . Like the adjacent images, it too is an object of worship; devotees bow to it as they file past and place offerings of flowers and money on its pages.

Near the entrance to the plaza is a small tent housing the equipment that controls the sound and lighting system. Festive illumination and powerful amplification are indispensable parts of religious events in India these days, and the arrangements for the Gyan Vapi program are typically elaborate. The entire mandap[*] is wired for light and sound, with tube lights and loudspeakers mounted on every post, a flickering, multicolored marquee around the images, and hanging microphones to pick up the chanters' voices. The broadcast range of the festival does not end at the boundaries of the plaza, however; a tangle of wires emerging from the sound tent activates a network of some three hundred loudspeakers installed throughout several square miles of surrounding neighborhoods in central Banaras. As I cycled to the program each morning from the southern part of the city, I encountered the first loudspeakers at the

Godowliya crossing, more than a kilometer from Gyan Vapi. From that point on I could follow what was going on in the mandap[*] .

Such large-scale broadcasting of a religious event struck me as rather unpleasantly intrusive, particularly as I supposed the installation of loudspeakers was imposed on the community by the wealthy organizers of the festival. My conversations with shopkeepers and residents in adjoining neighborhoods altered this impression, however, for no one complained about the loudspeakers and in fact the majority of the comments that I heard were positive. "You don't have to leave your shop to go to the program," remarked one merchant, "you can just listen whenever you feel like it." Moreover, I learned that most of the speakers were set up at the request and expense of groups of residents themselves. According to a bank officer who lived near the Vishvanath temple, the cost of installing each speaker (about seventy-five rupees) was met by taking up a collection (canda ) among area residents. "Then it is going from 5:30 in the morning till 11:00 at night," he said with apparent satisfaction, "and you can just listen whenever you feel inclined to give your attention."

Although the two daily sessions that constitute the Gyan Vapi festival—morning recitation and evening exposition—are thematically linked and form a cohesive event in the minds of participants, they are structurally quite distinct. The kinds of performance that occur in the two sessions are discussed separately. Here I confine myself to the morning sessions and make only passing reference to the exposition programs, as these are treated in detail in Chapter 4.

The Reciters

The daily program begins with early-morning arti to "awaken" the images; this is the responsibility of the attending priest and is of little public interest. Preparations for the program really get under way between 6:30 and 7:00 A.M. , when the hired reciters begin assembling in the enclosure. During this time, a group of Muslim musicians dressed in brocaded coats and caps take their seats on a small dais near the entrance and begin playing a morning raga. The sound of shehnai and tabla drifting over the misty ghats and through the bazaars of the awakening city announces in a most elegant fashion the approaching start of the program. A goldsmith from the nearby jewelers' bazaar pointed out to me with satisfaction the presence of the musicians and the absence of blaring Hindi film music, so common at public events; "You see, here they want to create a religious and cultural atmosphere."

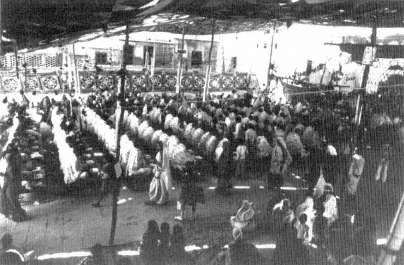

Figure 7.

One hundred eight uniformed Brahmans chant the Manas at the

Gyan Vapi festival

Just as the musical overture betokens the good taste and largesse of the organizers, the number of reciters confirms the grandeur of conception of this "great sacrifice." There are to be, as the banner on the main street announces, 108 Brahmans chanting the Manas , and the morning activities of workmen in the plaza include the setting up of nine rows of low platforms, on each of which, as at a banquet table, places are set for twelve reciters—with woven mats, wooden bookstands bearing uniform Gita Press editions, and copper vessels and spoons for ritual oblations. On the first day, reciters are also presented with yellow dhotis and Ram-nam shawls; these are to be their costume throughout the program. The number 108 is auspicious, and so determined are the organizers to maintain it at all times that they station two "spare" reciters on a side platform, ready to assume the place of any who may need to attend to nature's call.

Participants are selected six days before the program in an examination conducted by the chief reciter. The criteria for selection are simply that one be able to read and be sufficiently conversant with the Manas to be able to chant it at varying speeds. However, admission to the examination is restricted to persons possessing an official entry form, and there is brisk competition to obtain these—one reciter told me that they are sometimes sold for as much as one hundred rupees. Although

the Gyan Vapi program is the oldest and best known of the growing number of Manas- recitation festivals held in Banaras each year, it is not for prestige alone that Brahmans vie to participate in it. Nor is it for the official payment (daksina[*] ) given by the organizers—in 1982 a token fifteen rupees plus the tangible gratuities (dhoti, shawl, etc.) already mentioned. The great material benefit of participation in this program comes in the form of gifts in cash and kind, received from the public in the course of the recitation. The giving of gifts to Brahmans has always been regarded (especially by the Brahman authors of legal texts) as a meritorious and purifying activity, and legends celebrate the generous gifts that ancient kings gave their ritual specialists on the completion of Vedic sacrifices. In the same way, the patrons of this "sacrifice," the householders and widows of the Marwari business community, expect to gain merit by conferring gifts on the reciters, visible and publicized merit, one may add, since the giving is done in front of spectators and is announced over the far-flung audio system.

This gift giving can occur at any time, and some of the more humble sort takes place every day; elderly ladies, heads respectfully covered, thread their way down the long lines of chanting Brahmans, placing a banana, sweetmeat, or ten-paise coin in front of each, and then "taking the dust" of his feet on their foreheads. But the most lavish giving occurs on days when the recitation is dominated by a joyous event: Ram's birth (Day Two), marriage to Sita (Day Three), victory over Ravan (Day Eight), and enthronement (Day Nine). On these days the reciters come equipped with cloth bags to carry home the "loot" they are sure to receive.[47] This includes, by the end of the program, as much as four hundred rupees cash, as well as such practical items as wool blankets, cotton scarves, and stainless-steel bowls—all donated by local merchants. Each presentation is announced by the chief reciter, who interrupts the chanting at the end of a stanza to read, from a slip of paper handed to him by a member of the organizing committee, some such message as "Shrimati Nirmala Devi, in memory of her heaven-gone husband, Seth Raghunandan Lal-ji, presents to the gods-on-earth on the auspicious occasion of the Lord's royal consecration a daksina[*] of two rupees each." The announcement is greeted by a loud cheer from the assembled "gods," who then resume their recitation. Gift giving reaches such a pitch during the description of Ramraj on the final day that the

reading is interrupted after virtually every stanza by an announcement of this sort.

The Brahmans are honored in other ways as well. On their arrival each morning, their feet are ceremoniously washed by a member of the organizing committee, an elderly merchant known for his exceptional piety. And each morning's session is broken by a forty-five-minute rest period during which reciters are served a substantial snack of tea, savories, and fruit. A different family undertakes the provision of refreshments each day, and the name of the host is duly announced before the break.

Beginning Each Day's Program

The reciters come from all over the city and from as far away as Ramnagar—roughly ten kilometers distant, on the other side of the Ganga. All are supposed to be present and ready to begin by 7:00, but the program rarely starts on time -and many participants straggle in between 7:30 and 8:00. It is autumn and there is a misty chill in the air, but here and there shafts of sunlight stab through openings in the mandap[*] . While the musicians play and the washing of feet goes on near the well platform, reciters stand around chatting or slowly change into their festive uniforms. The unhurried atmosphere changes to one of feverish activity, however, at the arrival of the chief reciter, the sternly venerable Shiva Narayan. A dignified man of perhaps seventy-five years, whose association with the festival dates back more than a quarter of a century, Shiva Narayan slowly enters the enclosure, pausing at intervals to receive the homage of the many who come forward to touch his feet. He then prays silently before the diorama while late arrivals scurry to their places to avoid incurring their leader's displeasure. For in this most unpunctual of cities, Shiva Narayan is known to be a stickler for punctuality, at least where Manas recitation is concerned.

This trait is forcefully demonstrated on the third morning of the program, when the leader takes his seat on the podium somewhat earlier than usual, to discern a less-than-full complement of reciters filling the neat rows in front of him. Waiting extras are delegated to fill two of the empty places and the preliminary rituals are begun. Meanwhile, several of the offending Brahmans straggle in and attempt to make their way as unobtrusively as possible to their assigned places. None escapes the leader's stern gaze, however, and the ritual is periodically interrupted by a humiliating exchange such as the following (all, of course, broadcast to the city at large):

Figure 8.

Shiva Narayan, the chief reciter at Gyan Vapi in 1982 (note the

places set for two "spare" reciters to the right of the dais)

SHIVA NARAYAN : | YOU there, fifth row, middle. Come up here! (embarrassed silence as the Brahman reluctantly shuffles forward) All right now, tell us, why are you late? (mumbling and shuffling of feet) Come on, speak up! What's your excuse? |

BRAHMAN | (weakly): I was doing my puja-path[*] . . . . |

SHIVA NARYAN (loudly and with obvious sarcasm): | Oh you were doing your puja-path[*] ! And what do you think we're doing here? (pause to let laughter subside, then sternly) You were supposed to be here at 7:00, and you have kept us all waiting. (pause to let it sink in, then, peremptorily) Go, sit! |