The Enthronement

Two days after Bharat Milap I attended the performance of Ram's enthronement (rajgaddi ) in the garden compound at Lohatiya. The atmosphere could hardly have been more different from that of the frenetic and spectacular Milap. The same little boys who, two days before, had been the focus of the straining eyes of a vast multitude now sat casually on an open-air stage in a small garden, surrounded by the organizers and a handful of adult actors. And even though this performance too had been announced in the newspapers and no effort was made to exclude anyone, the total attendance during the course of the evening cannot have amounted to more than a few hundred persons. Indeed, the atmosphere was so casual that I felt I was witnessing a private party staged by the organizers for their own amusement. The child actors were in full costume—gorgeous silk robes and crowns for this special night—but they hardly seemed to be in "character"; much of the time they were lounging idly on the dais or playfully chatting among themselves, seemingly oblivious of the activities of the adults. The latter were in high spirits; everyone seemed to know everyone else, and the atmosphere suggested a backstage party after a successful opening night. Yet this was neither a party nor a rehearsal, but an actual performance of the lila of Ram's enthronement. What was one to make of it?

Amid the casual ambience, the expected sequence of events did unfold, after a fashion. The chief Ramayani, Pandit Bholanath Upadhyay, invited Ram to come sit with him near a small fire altar, where they were joined by several other Brahmans. The Manas passage describing the royal consecration was sung, and then the Brahmans began chanting Vedic mantras while their leader, smiling broadly, showed Ram what to do, guiding his little hand as he spooned oblations into the fire at appropriate intervals. While the ritual proceeded, the "party" continued all around. Vibhishan lounged at one end of the dais, conversing with an elderly devotee. Bharat and Sita played guessing games, periodically dissolving into giggles; Shatrughna fell asleep. Other groups of people sat in the garden chatting and paying no attention to what was going on. Throughout most of the evening (the ceremony began after 9:00 P.M. and continued for several hours) there were, with the exception of myself, no spectators; there were only participants, either in the lila itself or in the "party" that surrounded it. As the evening wore on, I found myself increasingly puzzled by the nature of the performance I was witnessing. It seemed inconceivable that the chuckling adult participants in the fire

ceremony, much less the inattentive onlookers, actually believed that the little boys were really the divine characters of the Ramayan. Was any "willing suspension of disbelief" possible in such a casual, even chaotic atmosphere?

But when the fire ritual concluded, an interesting thing happened. Upadhyay took Ram by the hand and led him to the marble throne platform at one end of the open-air stage. Sita, Lakshman, and Bharat followed; even little Shatrughna was roused from his nap and escorted over. The red-suited Hanuman donned his enormous brass mask and stepped forward, fly whisk in hand; a glittering silk umbrella was unfurled. Suddenly everyone in the garden was attentive. A tableau had taken shape: Ramchandra was enthroned in glory, Sita at his side, in the midst of his beloved brothers and companions. It was the climactic vision of the Manas , like Tulsi's own reputed first lila ; the nearly full moon of Sharad rode in the sky overhead. The Ramayanis took their places before the dais and intoned a hymn of praise from the Gitavali , and a steady stream of neighborhood people began to file through the garden gate for darsan .

Another performance followed: a long red carpet was unrolled at the foot of the throne, and Upadhyay stood to one side of it. The adult characters in the lila —Hanuman, Sugriv, Vibhishan, and the others—formed a queue at the far end. While "Ram" lounged casually on the throne, looking boyishly amused, the chief Ramayani addressed him in the reverent and formal language of a royal minister: "Divine Majesty, King of Kings, Lord Ramchandra!" He then began presenting each player to him with a brief introduction that was both reverent and, apparently, intentionally amusing:

Your Majesty, here before you is Sugriv. You know, Lord, he is a great devotee of yours, and he has done an awful lot for you. He bit off the nose and ears of Kumbhakarna, you'll recall. [laughter from onlookers] He attacked Meghnad too, and Ravan as well, and altogether he has suffered a lot on your account! Please be merciful, and bestow your grace on him.

While this patter was delivered, the player in question executed a series of seven full-body prostrations, beginning at the far end of the carpet and ending at the foot of the throne. These were accompanied by many chuckles of amusement from onlookers, both at the mock-seriousness of the introductions and at the difficulty with which some of the players—older men in elaborate, constraining costumes and heavy masks—executed their bows. These were anything but casual, however; each pros-

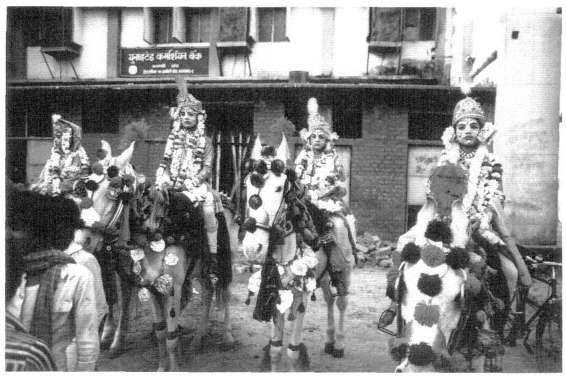

Figure 23.

A procession of boys adorned as Ramlila svarups

tration, achieved with no little huffing and puffing, was total. The man lay flat-out, arms extended toward the throne. Arriving at its foot, each player knelt and removed his mask, revealing a forehead beaded with sweat but a face grave and composed. His reward was forthcoming: the little Ram leaned forward and dropped a garland around his neck.

Reflecting on the evening's performance—on what seemed to me its incongruous conflation of high emotion and low comedy, casual ambience and occasional ritual intensity—I recalled a line from one of Hess's writings on Ramlila and its devotees: "people who grew up in easy intimacy with the God of personality and paraphernalia, the God who has characteristics like their uncles and cousins and is often as common and unheeded a household item."[62] The evening's experience had clarified a point often made by lila aficionados: that the little boys in gilded tiaras really are both children and gods. They are assumed to be guileless and innocent, free of the worries and compulsions of adults. Yet they are not merely blank screens on which devotees project the God of their imaginations; "attributes" are of the essence here, and the ones that the boys possess—innocence, physical attractiveness, Brahman-hood (equated with both social and religious prestige)—are essential ingredients in what they become. The boy chosen as a svarup is like the unblemished nim tree that the woodcarvers of Puri select, once every twelve to nineteen years, for their new image of Jagannath, Lord of the World.[63] Just as the Jagannath devotee may be aware that the image he adores was once a tree, so the Chitrakut spectator may recall, at times, that the boy beneath the crown is so-and-so's son, lives in such-and-such lane, and so forth. At the same time this boy possesses, by virtue of his attributes, the authority (adhikar ) not merely to represent but to become Ramchandra, just as the right kind of tree becomes Jagannath. And having become the part, he can offer something that every devotee craves and even temple images cannot bestow as tangibly: familiarity and intimacy with God; the chance to do seva ("service," connoting both formal worship and actual physical attention) and to experience "participation," which is one of the truest translations of the word bhakti . Each episode of the Chitrakut Ramlila affords a different kind of participation: the mass participation of the Milap, when the lila expands to incorporate the whole city and the auspicious paradigm of the

reunited brothers reaffirms familial and social hierarchies; and the intimate participation of the smaller performances, when large public symbols are replaced by near-private intimacies and grownup devotees play house with a child God.