Five

Words Made Flesh: The Text Enacted

O Garuda, even one who knows Ram's reality

yet remains devoted to these acts.

For the fruit of that knowledge is this lila—

so say great sages adept in self-restraint.

7.22.4,5

The Ramlila Tradition

The annual reenactment of the Ramayan story as a series of folk plays—the Ramlila —is among the world's most popular dramatic traditions: a form of live theater that reckons its audience not in hundreds or thousands, but in millions. Norvin Hein's assertion that "there must have been few North Indian villagers in the first half of the twentieth century who did not live within an evening's walking distance of a Ramlila during the Dashahra season" probably still applies in the century's latter half.[1] But even though the Ramlila is a widespread tradition, it is far from a homogeneous one. Its productions range from modest three-to-five-day affairs staged by a handful of village enthusiasts who double and triple up on major parts to month-long spectacles involving dozens of actors, musicians, and extras and attracting live audiences that may exceed a hundred thousand persons. The texts used for such diverse productions must obviously vary too; what they have in common—and it is this, in part, that makes possible an assertion of the fundamental

unity of the tradition—is that the vast majority are based, directly or indirectly, on the Ramcaritmanas ; both historically and performatively, Tulsi's epic lies at the heart of the Ramlila tradition.

As the most celebrated and visible form of Manas performance, the Ramlila has long attracted the attention of foreign travelers and both Western and Indian scholars, and a small literature has accumulated on the subject.[2] Scholars have analyzed the Ramlila as a form of folk theater and festival and have compared it to the medieval Christian miracle play. Such comparisons, while not wholly inappropriate, have often been made on the basis of a relatively superficial observation of Ramlila performances, and some of the published accounts of the tradition have contained inaccuracies and overgeneralizations.[3] Even Hein's two chapters on Ramlila were based, as he himself noted, on attendance at only ten performances, supplemented by the observations of several Indian friends regarding their own local stagings. Yet daily attendance at a Ramlila can significantly alter one's perception of the event—a fact affirmed by traditional audiences—and the recent writings of Richard Schechner and Linda Hess, who as a research team attended the Ramnagar production regularly for two years, have added a new dimension to our understanding of these performances.[4] I shall have many occasions to refer to their ongoing research as well as to the earlier work of Hein and other scholars. My own approach in the present chapter is to examine several Ramlila cycles in the Banaras area from a variety of perspectives—historical, descriptive, and religious—with a focus on the role of the Manas text in the productions and on their relationship to the other forms of epic performance already introduced.

The centrality of lila in Vaishnava theology has been noted by many scholars.[5] According to a popular formula I heard more than once in

Katha performances, "the Lord has four fundamental aspects [vigrah ]: name, form, acts, and abode [nam , rup , lila , and dham ]—catch hold of any one of these and you'll be saved!" Each of the four elements in the formula points to an aspect of Vaishnava devotional practice: the repetition of the Lord's name (jap ); the ceremonial worship of his image (puja , seva ); and pilgrimage (yatra ) to the holy places associated with his earthly activities. But what does it mean to "catch hold of" his lila —his legendary adventures? One method is to hear them artfully recounted in recitation and Katha programs. But another method, and the one especially suggested by the term lila , is to witness them through some form of dramatic "representation." This understanding needs to be qualified, because Vaishnavas consider the Lord's acts to partake of his inherent nature and hence to be boundless and eternal. They do not have to be "re-presented" because they always exist, and the devotional activities through which they can be glimpsed are themselves aspects of the lila , in which devotees are privileged to share. In the broadest sense, lila may be said to be a way of life for worshipers of Ram and Krishna.

Vaishnava theologians distinguish between two kinds of lila: nitya (continuous or eternal) and naimittik (occasional).[6] The former refers to the Lord's cosmic activity (of which the universe is a by-product and reflection) and also to the daily ritual cycle of eight time periods (astakalin[*]lila ), which follows the scenario of a divine courtly routine. "Occasional" lila refers to the specific adventures of one of the Lord's incarnations and also their celebration and recreation by devotees. In such observances, the calendar unit shifts from the day to the year, with its larger cycle of festivals commemorating specific events in the cultic myth. Since most of these events are associated with places dear to the Lord, the cycle of the year becomes, for sadhus and other mobile devotees, a series of pilgrimages that reenact the Lord's own movements and bring worshipers to sites at which they reexperience his salvific deeds. Thus, for Ram Navami the goal of pilgrimage is Ayodhya, where devotees gather for nine days before the divine birth to sing songs of congratulation (badhai ) and where, at noon on the ninth day, a cacophony of bells, conches, and drums announces the blessed event. For Vivah Panchami (Ram and Sita's wedding anniversary), the preferred site is Mithila (Janakpur) in Nepal, where arriving pilgrims identify themselves as members of Ram's barat , or wedding party, and trade humorous insults with the people of the bride's hometown.[7] For really ambitious devo-

tees, the annual lila cycle may be demanding indeed. Snehlata, a famous sadhu of Ayodhya, is said to have recommended participation in the following site-specific festivals:

Mithila: | Vivah Panchami (November/December) |

Parikrama (February/March) | |

Holi (February/March) | |

Ayodhya: | Ram Navami (March/April) |

Jhulan (July/August) | |

Akshay Navami (November/December) | |

Ramnagar: | Ramlila (September/October) |

Chitrakut: | Divali (October/November)[8] |

All such Ramlilas involve elements of role playing and enactment, in some cases of a fairly abbreviated or symbolic sort and in others of a more elaborate variety. On the marriage day in Ayodhya, for example, wedding processions mounted by major temples wind through the city for hours. They consist of lampbearers, drummers and shehnai players, "English-style" marching bands (all requisites of a modern North Indian wedding), and of course the bridegrooms—Ram and his three brothers—astride horses or riding in ornate carriages. The grooms are usually svarups —young Brahman boys impersonating deities—but a few processions feature temple images borne on palanquins. After receiving the homage of devotees before whose homes and shops they briefly halt, the processions return to their sponsoring establishments, where a marriage ceremony is performed. The crowds of devotees attending these rites are not merely spectators; they are encouraged to take the roles of members of the wedding party. "Aren't there any Mithila ladies here?" a portly sadhu asked at one of the ceremonies I attended, casting a twinkling eye over the crowd. "How can we have a wedding without galiyam[*] ?" (scurrilous songs directed by the women of the bride's family against the groom and his relations). "We're here, to be sure!" a jovial-looking matron replied and launched into a song that evoked broad smiles all around. Such participation reflects a characteristic Vaishnava concern with entering into the fabric of mythic narrative.

Although lilas celebrating the deeds of Ram occur throughout the year, the term Ramlila commonly refers to a period within the yearly

cycle during which Ram's story is retold sequentially and in detail. To the majority of North Indians, it means a span of from nine to thirty days, culminating in the bright half of the month of Ashvin (October/ November), with the death of Ravan nearly everywhere staged on Vijaydashami—the "victorious tenth" of that fortnight. Alternatively but less commonly, the term refers to similar dramas staged during the nine nights of the bright half of Chaitra (March/April) leading up to Ram's birthday.

There still has not been, to my knowledge, a detailed study of the geographical extent of the Ramlila tradition, but it is clear that it extends beyond Uttar Pradesh and even beyond the Hindi-speaking region, although it is less predictably to be found, or more narrowly patronized, in fringe areas.[9] In the Garhwal hills, for example, Ramlila appears to have been introduced only in recent decades, largely by merchant groups that brought it from the plains, but the tradition has begun to be taken up by upper-caste Pahari Hindus.[10]Ramlila is likewise staged by many Hindus in Haryana, in some towns and villages in Rajasthan,[11] and by transplanted communities of Hindi-speakers in the cities of Bombay and Calcutta. In all these areas, however, it lacks the status of an almost universally patronized, communitywide event such as it has throughout much of the Hindi-speaking belt. In short, the popularity and patronage of the Ramlila appears to be roughly coextensive with that of the Manas .

In its heartland, the popularity of Ramlila and the scale on which its productions are undertaken seem hardly to have been diminished by the competition of newer forms of entertainment. Modern urban culture, far from turning its back on the pageant, has added its own embellishments, as is clear from this excerpt from a 1980 article in a New Delhi magazine.

Come October and big business groups host cocktail parties for press reporters and other close friends to announce their friendly competition—they are going to have a higher, gaudier Ravan, with mechanical movement in his

jaws, arms, and ears, yet. The effigies of the demons cross the hundred foot barrier and keep on soaring. . . . One Ramlila is sponsored by a cloth mill, and obviously cash is no problem. Much of it is spent on mechanical stage properties for the 10-day play, the highlight being a "flying" Hanuman. Ensconced in a canvas, steel and leather harness, the monkey glides down a steel rope-way as he brings an entire mountain so that Ram can find the herb which is needed to revive Lakshman. . . . Another Ramlila, the costliest of them all, is financed by the same tradesmen who are giving money to the crusade to pressure the government to do away with sales tax and other bindings cutting into their profits and sales. Costumes of Sita are gold-braided, and the crowns of the kings are gilded. Top political leaders vie with each other for the honour of garlanding the human gods, as the organisers scramble for keepsake photographs with the VIPs.[12]

Apart from these examples, India's capital city has a famous old Ramlila , said to have been started two centuries ago by Hindu soldiers in the Mughal army, who staged it on the banks of the Yamuna; about fifty years ago its major scenes shifted to the huge field that separates the old and new cities and is known throughout the year as Ramlila Maidan. Its climactic Ravan[*]vadh (slaying of Ravan) incorporates giant puppet effigies, and like the comparable scene in other large urban productions, attracts a crowd of several hundred thousand persons.

Yet despite the impressive attendance at such pageants, the real significance of Ramlila for the average Delhi citizen is better suggested by the numerous neighborhood productions staged concurrently, though with far less publicity and fewer elaborate props. The same magazine article speaks (doubtless with some exaggeration), of

the thousand-odd streetside versions that flower during the ten days along lanes and bylanes of the Capital and its suburbs, converting open plots, pavements, blocked roads and fallow fields into small islands of colour, gaiety, and a touching piety not seen in the commercial fervour of rich religionists. Organised by small ethnic groups—the Paharis at one corner, the Jats in another, Biharis, Punjabis, and a host of others in their own localities—each little Ramlila is obviously a labour of love.[13]

That the annual Ramlila festivals provide color and gaiety is readily apparent to even the most casual observer. But to understand the religious dimension of these performances—the "touching piety" that motivates them—we must delve deeper into their history and structure. To this end, we turn our attention to the Banaras region, the present heartland and presumed birthplace of the tradition.

The "Sport" of Kings: Evolution of the Banaras Ramlila

Solid evidence concerning the early origins of Ramlila is meager and there is little to add to the researches of Hein on the subject.[14] While noting that similar performances based on other Ramayan texts appear to have existed in Orissa at the beginning of the sixteenth century, Hein concludes that the dramas in their present form originated in the Banaras area either during or shortly after Tulsidas's lifetime and that their performance was from the beginning linked with the Manas text. He postulates an ancestor for both Ram and Krishna lila performances in an ancient, royally patronized tradition of Vaishnava dance-drama, which may have flourished in the Mathura region in the early centuries of the Christian era. Hein suggests that this Ur-tradition used trained adult musicians, mimes, and singers to enact Vaishnava legends and that its techniques are still reflected in the gestural and staging conventions of such diverse performance traditions as the kathakali of Kerala, the yaksagana[*] of Karnataka, and the nearly extinct kathak performances of the Hindi-speaking regions. He concedes, however, that this hypothetical ancestral tradition bore little resemblance to the modern form of lila dramas, apart from the fact that both served to mediate scripture. Moreover, the textual record shows a gap of roughly a millennium between the last mention of the "classical" ancestor and the earliest citation of its presumed "folk" descendant.

Although Hein offers appreciative accounts of contemporary Ram and Krishna lilas , his historical chapters risk conveying the impression that these are but derivative and corrupted vestiges of a vanished "great tradition" of Vaishnava dance-drama. Because centuries of Muslim rule had destroyed the bases of patronage and training, Hein speculates, simplified pantomime by child actors replaced an elaborate code of gestures that could only have been mastered by adults; because audiences and patrons no longer understood Sanskrit, vernacular mediations had to be provided for the ancient stories. Hein recognizes a certain genius in the folk dramas, but it is a genius of adaptation to admittedly adverse conditions; "simplification," he observes, "was the price of survival."[15] Yet the "revival" of Vaishnava performance genres beginning in the sixteenth century occurred in a milieu that, despite intervening centuries of Muslim rule, was perhaps not so unlike that of Hein's postulated

ancient tradition. With the gradual. decline of centralized Muslim authority, Hindu performance traditions again came to enjoy royal and aristocratic patronage, and they developed new forms and conventions of their own. Child actors were chosen to portray the central characters not because trained adults were unavailable but because they were unacceptable to producers; the vision of the enactment had changed—a change discussed in greater detail later. The shift from a temple or palace setting was consonant with the implicit philosophy of the bhakti movement, which sought to make religious teachings accessible to the masses; it also served the organizers' political and social aims. The forms of religious expression characteristic of bhakti —kirtan , bhajan, Katha , and lila —may reflect the Muslim political presence and the decline of large-scale temple cults, but they also display positive strengths of their own. The Ramlila is outdoor and peripatetic not because latter-day patrons could not afford to construct theaters but because the pageant came to express notions of cosmography and pilgrimage that aim at reclaiming and transforming the mundane world.

The legends that credit Tulsidas with the founding of the Ramlila in Banaras are associated with the claims of specific productions to being the city's original or adilila . Three productions presently claim this status: Tulsi Ghat, Chitrakut, and Lat Bhairav Ramlilas . Although the organizing committee of the Tulsi Ghat production, which today is sponsored by the Sankat Mochan Temple, dates back only to 1933, it claims to continue a tradition begun by the poet himself. An authority cited for this claim is the Gautamcandrika , the biography of Tulsidas attributed to Krishnadatt Mishra. A passage in this text describes Tulsi's activities during a certain bright fortnight of Ashvin:

Worshiping the nine Durgas on the ninth,

bowing his head to the sami tree on Vijaydashami,[16] he listened to the six lovely books

of the holy Ramayana[*] of Valmiki.

He fasted on the eleventh,

broke fast on the twelfth,

and accepted Hari's prasad on the thirteenth.

On the fourteenth, while gazing at the Ganga,

he heard the account of Ram's consecration. . . .

Having worshiped Valmiki, Hanuman, and the priest,

he produced the lila of Ram's consecration.

The full moon of Sharad adorned the umbrella.

Ram was resplendent on a throne of earth.

On his left side, Queen Sita,

on his right, Lakshman, whisk in hand.

The noble Bharat became crown prince,

Shatrughna attended to all duties.

The commander in chief was Hanuman,

bestower of auspiciousness.

The queens performed arti . . . .

Ram was king and Sita, queen.

Shouts of "Victory!" resounded through the world.

On Assi Ghat, beside the river of the gods.[17]

Aside from the question of its authenticity, the Gautamcandrika poses many textual problems. Its scholarly discoverer, Vishvanath Prasad Mishra, claimed to have copied it hastily from another man's rough notes, and it has been suggested that passages may have gotten out of sequence; moreover, many lines are simply obscure. At least one author has understood the whole coronation lila as a vision seen by Tulsi in his mind's eye as he sat contemplating the Ganga and listening to the recitation of Valmiki's epic.[18] However, the conventional interpretation, reflected in the above translation, regards the passage as an account of Tulsi's initiating a custom of enacting Ram's consecration at Assi Ghat on the full moon following Vijaydashami. Later, it is claimed, this simple drama was reorganized into a multiday affair using the text of the newly completed Manas . It is also claimed that the poet selected various sites in the area to stage specific scenes and gave them the lila names by which they continue to be known—for example, the neighborhoods of Panchvati and Lanka.

The Gautamcandrika's description suggests less a drama than a tableau: a living icon of Ram enthroned with Sita at his side, Lakshman and the other brothers in attendance, and Hanuman standing in adoration while the queens wave the arti tray and sing a hymn of praise. Such tableaux vivants still form an important element in Ramlila productions, as well as the major element in jhanki (glimpse or tableau), a related performance tradition.[19] Hein found no textual evidence earlier than the late nineteenth century for the form of jhanki he witnessed in Mathura, but the relationship of this genre to lila dramas needs further study. Awasthi is of the opinion that tableaux accompanied by text recitation and ceremonial worship represented the original form of

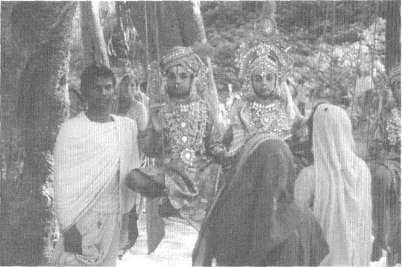

Figure 21.

A living tableau (jhanki) of Ram and Sita, at Mani Parvat,

Ayodhya, during the Jhula Festival, August 1987

Ramlila , which is still reflected in primarily pantomime-based (abhinay parak ) productions—as distinguished from the dialogue-based (samvadparak ) productions she assumes represent a later stage of development.[20] Another scholar of Banarsi Ramlila , Bhanushankar Mehta, suggests that the jhanki tradition itself is an outgrowth of Vaishnava Temple worship, wherein the divine images are displayed with ever-changing adornments of costumes and settings.[21]

The founding of both the Chitrakut and Lat Bhairav Ramlilas is attributed to a Ram devotee known as Megha Bhagat or Narayandas. Some legends claim he was an older contemporary of Tulsi and had been staging a Ramayan play for some time using the text of Valmiki, when Tulsi approached him and suggested using the Manas instead.[22] Together they reorganized the drama into its present twenty-one-day form, staged at various sites in the northern part of the city. But the more usual version has it that Megha was a disciple of Tulsi and began the produc-

tion shortly after his master's death in 1623.[23] The Chitrakut organizers claim that Ram appeared to Megha in the form of a small boy and presented him with a tiny bow and arrow; these are still preserved in a temple known as Atmavireshvar and are publicly displayed once a year. Another important element in the legend is that Megha was promised physical sight (darsan ) of the Lord at the climax of the lila and collapsed and died during the scene of the reunion of the brothers—the Bharat Milap—which is still regarded as the most powerful performance in this cycle.

Although popular tradition offers no conclusive proof for the antiquity of a given lila , there are several reasons to assume that the Chitrakut production is indeed of greater age than most others in the city. In Awasthi's terms, it is pantomime-based and lacks the dialogues now standard in most other productions, which appear to represent a nineteenth-century innovation. The Chitrakut version's failure to incorporate them may indicate that it follows an older tradition in which the actors did not speak or even, for the most part, act but simply made themselves available for darsan to assembled devotees who listened to recitation of the Manas . It is noteworthy that the titles of several episodes in this production's printed schedule include the word jhanki .[24] The Ramayanis (in this context, "Manas -reciters") chant the entire epic, occasionally supplementing it with verses and songs from other works by Tulsidas; while they recite, the actors perform an abbreviated and sporadic pantomime, acting out some scenes but omitting others.

Costuming and makeup in this production also follow a distinctive set of conventions. The faces of the boy actors are not adorned, as they are in most productions, with sequins or other elaborate makeup, but are merely colored with a yellowish clay known as "Ram's dust" (Ramraj ), said to come from the pilgrimage site of Chitrakut and used to make the forehead mark of many Ramanandi sadhus. The boys' headgear is also of a peculiar design; for scenes of forest exile, Ram and Lakshman wear crowns decorated with parrot feathers and other natural ornaments, and their garlands are of tulsi leaves. A devotee explained these conventions to me as follows: "Megha Bhagat was a poor man; he could not afford costly adornment. He just took small boys into

the forest and used whatever he found there: clay, feathers, leaves. That's why we still use this kind of makeup."[25]

Another notable point about the Chitrakut Ramlila is its great status in the city, even though, with the exception of the Bharat Milap, most of its performances attract little public participation. It is especially significant that the maharaja of Banaras, who is preoccupied with his own concurrently running dramatic cycle at Ramnagar, absents himself on one evening each year in order to attend the Chitrakut Bharat Milap: his presence suggests that this event predates the beginning of the royally patronized pageant and that, already in the early nineteenth century, its status was such that the maharaja's presence was necessary.

The development of a royally sponsored Ramlila in the Banaras area was the result of many factors, not least of which was the city's association with Tulsidas and his epic and the presence of already-established productions that could serve as models. In discussing the development of Katha , I outlined some of the sociopolitical factors that encouraged eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Hindu rulers to patronize the Manas exegetical tradition. The Banaras kings' special cultivation of the Ramlila must likewise be viewed against the background of their dynasty's bid for power in the region. In 1740 when Balvant Singh, the son of an ambitious local tax farmer, assumed the title "raja of Banaras," he did so as a client of the nawab of Avadh (Oudh), the paramount political power in the region, who in turn still displayed a nominal allegiance to the weak Mughal regime at Delhi. As Bernard Cohn has pointed out, the Banaras "ruler" was more correctly a middleman in a complex system in which authority was parceled out at many levels and the distribution of power was constantly being renegotiated:

The Raja's obligations to the Nawabs were the regular payment of revenue and provision of troops when requested. The Raja of Banaras at every opportunity tried to avoid fulfillment of these obligations; and on several occasions the Nawab sent troops to try to bring his subordinate to terms, if not to capture and kill him. On these occasions, Balvant Singh would retreat with his treasure and army to the jungles of Mirzapur. After a time the Nawab, distracted by similar behavior in other parts of his state or by his intervention in imperial politics, would compromise with Balvant Singh and withdraw, at which time Balvant Singh would resume his control. . . . A balancing of relative weakness appears to have been central to the functioning of the system. The Nawab could not afford the complete chaos which would result from the crushing of the Raja.[26]

The nawab depended on the raja because no one else was able to guarantee collection of revenue in the region (even if relatively little of it actually reached the nawab's treasury), and the raja was in a similar relationship of dependency on and intermittent conflict with his subordinates, numerous petty rajas and landlords who likewise controlled revenue and troops and were the primary intermediaries between the raja and the peasants.

That the nawab of Avadh was Muslim and the raja of Banaras Hindu may at times have given an ideological edge to Balvant Singh's ambitions, although it should be noted that some of the raja's most intractable enemies were local Hindu chieftains who disputed his authority, and that the Shi'a nawabs were highly catholic in religious matters.[27] The issue was a matter less of communal identity than of royal legitimation, for this was what the nawab provided to the Banaras rulers—a legitimation that ultimately derived from the premise of Mughal dominion. The Monas Rajputs of Bhadohi, for example, who were staunch rivals of Balvant Singh, held their land under an imperial decree from Shahjahan. Even after defeating them the raja could not finally annex their territory until he had received permission from the nawab, the nominal Mughal representative in the region. The raja's dependency was revealed again on Balvant Singh's death, when the nawab initially refused to recognize his successor, Chet Singh (ruled 1770-81); only on the intervention of Warren Hastings and the provision of lavish gifts from the aspiring prince did the Avadh ruler consent to "tie the turban" on Chet Singh, symbolizing his recognition of the latter's claim. As Cohn has noted, "Power the Raja had; but he needed authority as well. Even though the Rajas' goal in relation to the Nawabs was a consistent one of independence, they could not afford to ignore the ground rules and had to continue to seek the sanction, even if it was ex post facto, of their super-ordinates, the Nawabs."[28]

The splendor of Indo-Muslim culture had powerfully influenced the values and tastes of the Hindu elite of North India, but by the middle of the eighteenth century the Mughal imperial mystique must have been increasingly bankrupt. In 1739, the year before Balvant Singh assumed his title, Delhi was devastatingly looted by a Persian adventurer who carried off the emerald-encrusted throne of Shahjahan. Urdu poets like

Mir, who fled east to Avadh, lamented the downfall of the capital, its deserted streets and ruined bazaars.[29] Within the century the reigning motif of Indo-Islamic culture would become one of decline and lamentation over lost glory—a theme of little appeal to ambitious kings in search of positive and victorious symbols.[30] I suggest that the Banaras rulers saw a symbolic alternative to the Mughal ethos in the theme of Ramraj as articulated by Tulsidas. This vision of an ancient, universal Hindu empire supplied the aura of legitimacy and authority that the rulers had initially been obliged to seek from the nawabs; moreover, the epic's emphasis on social and political hierarchy and on the properly deferential behavior of subjects and subordinates could serve as a chastening example to the raja's rebellious underlings.

A further motive for the Banaras kings' patronage of the Ram tradition may have been their desire to maintain amicable relations with the powerful Ramanandi order of sadhus. Several recent studies have pointed to the economic and military strength of mendicant orders during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and to the fact that, ironically, Ramanandi "detached ones" (vairagis ) not only controlled considerable wealth but also served as mercenaries in royal armies. A mobile population that was difficult to control, sadhus often traveled in armed bands and seem to have virtually controlled the trade in certain commodities.[31] The Banaras kingdom was roughly equidistant from three important Ramanandi centers: Chitrakut in the southwest, Ja-nakpur in the northeast, and Ayodhya in the northwest—the latter began to flourish again as a pilgrimage center after it ceased to be the capital of Avadh in 1765. The Banaras rulers used the conspicuous patronage of Ramanandis—especially at the time of Ramlila , when thousands of sadhus were invited to set up camp in the royal city and were fed at the raja's expense—not only to guarantee the sadhus' loyalty but also to turn their own upstart capital, on the "impure" eastern bank of the Ganga, into a major center of pilgrimage.

These developments crystallized during the reign of Balvant Singh's

grandson, Udit Narayan Singh (1796-1835). At least four legends have been offered to explain this king's decision to become a Ramlila patron.

1. The maharaja, saddened because he had no offspring, was advised by a sadhu to sponsor a Ramlila and prepare a great feast for the holy men who would attend it. By serving them and drinking their caranamrt[*] (water in which their feet had been washed), his wishes would be fulfilled.[32] 2. The maharaja used to attend the Bharat Milap of the Chitrakut Ramlila , but one year he was delayed by bad weather. When he reached the site, he was disappointed to find that the Milap had already taken place. He returned home resolved to create his own lila by expanding the production in neighboring Chota Mirzapur.[33] 3. The maharaja always used to attend the Ramlila established by Tulsidas at Assi Ghat. One year the crown prince fell ill and doctors gave up hope of his recovery. His father continued to cross the Ganga to attend lila as usual. One day he prayed to Ram for the prince's recovery; at once the svarup removed his garland and told the king to put it on the prince. The latter's miraculous recovery so impressed the king with the power of lila that he resolved to commence his own production by restructuring that of Chota Mirzapur.[34] 4. Every year on Vijaydashami, Udit Narayan used to carry out the Kshatriya custom of worshiping the royal weapons, mounts, and emblems. Then he would ride out to the border of Ramnagar to have the darsan of Ram at the Chota Mirzapur lila . One year he was delayed and found the lila finished. When he returned home disappointed, the maharani proposed that the court stage its own production the following year and offered her personal funds to cover its expense. Three years later, she instituted the custom of inviting the boy actors to the fort for a feast on the final day.[35]

Two of the above legends have a common feature: the king's arriving late at an existing production, finding that it has been held without him, and resolving to avoid such disappointment in the future. In fact, the

present-day organizers of the Chitrakut Bharat Milap make a great point of the punctiliousness with which this lila is scheduled: the embrace of the brothers must occur at an astrologically determined moment; even though the maharaja is an honored guest, it is possible that, were he unduly delayed, the pageant would proceed without him. At Ramnagar, however, the presence of the maharaja is essential and no performance can begin until he has taken his place on the scene. The great majority of Ramlilas are likewise pancayati , or publicly produced and supported by a general collection. The stories seek to explain (and perhaps also to justify) the striking fact that at Ramnagar a king chose to make a lila distinctively his own—to associate it in a special way with his family and status.

A second point of interest is that nearly all the accounts mention the Chota Mirzapur lila as the production taken over by the king, and one adds the detail of the Vijaydashami excursion. The elaborate puja of royal weapons, horses, and elephants performed on that day, usually in connection with the worship of the goddess Durga, is an ancient and widespread Kshatriya observance, which is not everywhere explicitly linked with the Ramayan narrative. This ceremony is crowned by a martial excursion—a sallying forth to cross the borders of the kingdom that, like the movements of the sacrificial horse in the ancient asvamedha ritual, amounts to an assertion of overlordship and a challenge to neighboring kings. In the traditional Hindu conception of monarchy, the king's authority radiates out from his person and when he enters a new region, its people come under his protection. Some commentators offer a Vaishnava gloss: the king rides out with his army to offer assistance to Ram in his final battle against Ravan. But in the political climate of the early nineteenth century, Udit Narayan's gesture may have represented less an act of assistance to Ram than an effort to be like him—a local restatement of world conquest. It was also consonant with the ideological and strategic concerns of a dynasty that chose to build its fortress-palace on the eastern bank of the Ganga, which sacred geography regarded as impure, and which, according to Awasthi, had a predominantly Muslim population—a "wilderness" beyond the City of Light. This vision reappeared in the naming of the royal capital: Ramnagar—a "City of Ram" to advertise to the whole region the prestige and piety of a parvenu dynasty of Bhumihar tax farmers.

One of the most striking features of Ramlila plays is their outdoor and peripatetic method of staging: as the story shifts from one location to another, actors and audience physically move. This pattern may have

first developed in connection with the Krishna plays of the Mathura area, especially the annual van yatra , a multiday pilgrimage through the forests and fields of Braj to sites associated with Krishna's exploits, where enactments of the appropriate legends were presented. The development of this tradition was an outgrowth of the work of the Chaitanyaite goswamis of the sixteenth century, who "rediscovered" in their meditative wanderings countless "lost" sites associated with Krishna.[36] Such a reclamation of a religious landscape had political implications. The goswamis were sent forth from eastern India, from a sect based in the still-independent Hindu kingdom of Orissa, to Mathura, a mere thirty miles from the Mughal imperial capital at Agra. The holy places of the region needed rediscovery, it is said, because they had become hidden during centuries of mlecch (barbarian) rule. Somewhat later, the holy city of Ram was resurrected in much the same way; indeed, the imaginative recovery of Ayodhya—by pious devotees and hucksters alike—continues today, with each newly built temple claiming to mark the site of some special place or event in Ram's life.

Udit Narayan's reclamation efforts were closer to home. Utilizing the existing tradition of peripatetic Ramlila plays and assisted by his spiritual advisers, he began a physical overhaul of his capital city: "After taking charge of the Ramlila held on the border of Ramnagar, he established a place very close to the royal fort as Ram's birthplace, Ayodhya, and started the lila from the center of town. Accordingly, after very careful consideration Ayodhya, Janakpur, Girija Temple, Chitrakut, Panchvati, Pampasar, Lanka and so forth were constructed at appropriate sites, and the Ramlila was in all ways made permanent."[37] The environments built by the king were spread over an area of some fifteen square miles and included a number of impressive permanent structures. Each location was given a name derived from the epic's geography, by which it became known throughout the year. "Ayodhya," built in the shadow of the fort, was a walled enclosure of red sandstone with a high facade at one end to represent King Dashrath's palace, and space for about seven thousand spectators. "Janakpur," two kilometers away, was an equally large compound with several lofty sandstone plinths; the vast field of "Lanka," with its earthen ziggurat representing Ravan's fortress, was set far to the southeast on the border of the raja's territory.[38] The template of the Ramayan was laid over the whole country-

side in between, radiating out from the king's seat of authority and transforming every field, forest, and tank into a permanent setting for mythic theater. Two processional avenues were constructed, flanked by a uniformly built bazaar; they resemble nothing else in the helter-skelter urban layout of Banaras and may show the influence of Jai Singh's Jaipur, but they lend themselves well to the grand processions of the lila and its climactic Bharat Milap, which occurs at their intersection in the city's main square. Ramnagar tradition holds that the whole project was overseen by venerable Ramayanis, who were guided by inner vision and their profound knowledge of the Manas to sensitively choose the most appropriate sites for each lila —sites that resonated in some mysterious way with the original Ramayan locations so that, as in Braj, their very soil was felt to participate in the myth.

As the pageant expanded and new environments were created, existing sites were also incorporated into the emerging design. In the northeast, near the intersection of the Chunar and the Grand Trunk roads, a complex consisting of a large Devi temple flanked by a vast tank and an expansive walled garden, begun during the troubled reign of Chet Singh, was brought to completion by Udit Narayan and his successor and put to use in the plays.[39] The huge temple, with its hundred-foot spire, became known as Sumeru, after the mythical world mountain atop which Brahmalok, the world of Brahma, is situated. It was used for one of the opening scenes, in which the gods go to Brahma to plead for relief from Ravan's depredations. The vast tank became the "Milky Ocean" (ksir[*]sagar ) on which Vishnu rests, recumbent on the serpent of infinity. The walled enclosure became Rambag, "Ram's garden," the site of the final events in the narrative, when the hero repairs there to give instruction to his subjects.

The scale and design of these sites testify to the ideological concerns of the fledgling dynasty: the temple is one of the largest in the region and its iconography shows a conscious blend of Vaishnava and Shaiva/ Shakta elements, displaying the dual loyalty of the Banaras kings. The mammoth tank with its four sandstone ghats rising in endless symmetrical tiers may have been intended to represent Manas Lake itself, nestled at the foot of the world mountain, Sumeru/Kailash. Here the lila begins: the Lord who is to take birth later in Ayodhya appears floating on the waters, as the world itself emerges at the beginning of a cosmic cycle. The Ramlila , like the Manas epic, emerges from the waters and spreads forth into our world.

As the lila expanded in space to fill the whole of the maharaja's little kingdom, so it also extended in time. According to Awasthi's sources, the old lila of Chota Mirzapur lasted for ten to twelve days (as most Ramlilas still do), but under royal patronage it grew to fill an entire calendar month, a complete unit of time by Hindu reckoning. Another, related expansion was in what might be termed textual fidelity; this was to be not merely a staging of the Ram story as recounted in the Manas but a ritual recitation (parayan[*] ) of the complete epic. Thus, even portions of the text that did not lend themselves to dramatic enactment—such as the long "introduction" and "epilogue"—were to be recited, extending the performance by a further ten days. Moreover, since ritual recitation has an implicit objective (in this case, the welfare of the kingdom) and involves an element of risk, the performance had to be bracketed with protective rituals: an elaborate preliminary puja of Ganesh, the Goddess, the text and its reciters, and the crowns, masks, and costumes of the actors; and a final ceremony performed within a week of the conclusion of the play, in which a Brahman completes an additional twenty-four-hour recital in a small Hanuman temple at the southern window of the fort "to make up for any omission or other error."[40]

Another notable innovation was the final feast of the kot[*]vidai (farewell to the fort), a ceremony interestingly analyzed by Schechner, who notes that it highlights the deities' symbiotic relationship with the royal family: "the Maharaja exists in the field of energy created by Ram, and Ram exists as arranged for by the Maharaja."[41] Significantly, modern Ramnagar promoters stress that their lila is a mahayajna , or "great sacrifice," the term used for Vedic royal rituals and present-day public recitations of the Manas —all ceremonies that promote intimacy and exhange between patrons and deities.

Udit Narayan and Ishvariprasad were the patrons and producers of this lila , but they were not its sole directors; the evolving drama represented a collaboration with some of the leading Manas scholars of the period. The "wooden-tongued" Kashthajihva Swami took a special interest in the lila and composed songs used in the nonrecitation portions of the text.[42] Another lila enthusiast was Raghuraj Singh (1833-79),

crown prince and later maharaja of Rewa, who was a devotee of the youthful Ram and took special delight in the scenes of Ram and Sita's "romance." At Ishvariprasad's request, he composed an epic poem in twenty-three cantos, entitled Ramsvayamvar[*] , from which several songs likewise found their way into the script.[43]

The most significant collaborator in lila development, however, was allegedly Harishchandra of Banaras, the poet and author who came to be known as the "father of modern Hindi literature." An enthusiastic lila goer,[44] Harishchandra was entrusted by Ishvariprasad with the task of modernizing the dialogues and is said to have recast their original Bhojpuri into a modified Khari Boli, the dialect of Delhi that he had adopted for prose writing. His revisions also reveal the inspiration of other texts; thus, in the "Bow Sacrifice" scene, he drew on Keshavdas's Ramcandrika to create a droll dialogue between two courtiers describing the arrival of the kings who will contend for Sita's hand—a comic and theatrically effective episode that has no counterpart in the Manas . According to Awasthi, the overall effect of Harishchandra's revisions was not merely to modernize the lila , setting its prose script in a dialect that was becoming popular in his time, but also to make it more theatrical.[45] Ishvariprasad was pleased with the poet's revisions and the Ramnagar lila became fixed in this form. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, the combination of royal patronage, Ramanandi participation, Banaras location, and innovative staging contributed to the growing reputation of this production and made it both a goal of annual pilgrimage and a model for many smaller-scale lila cycles.

Three Contemporary Productions

The importance of Ramlila in Banarsi life has not been adequately conveyed in scholarly writings on the city. Hein mistakenly reported that the tradition was in decline, that the entire Manas was no longer performed at Ramnagar, and that the city as a whole mounted only three productions.[46] More recently, Eck, in her description of the city's festival cycle, mentioned only two productions and gave the impression that

participation in Ramlila was restricted to the Kshatriya community.[47] In fact, Ramlila is a flourishing and all-but-ubiquitous tradition in Banaras, enjoys the broadest patronage, and is represented by productions that are looked on as exemplary throughout North India. For although. other cities also boast old and famous productions, it is widely felt that the inhabitants of Banaras stage Ramlila with special flair and enthusiasm (dhum-dham ), and Banarsi productions are often highlighted in popular magazines at Ramlila time. The narrator of Premchand's short story "Ramlila," which concerns a small town production, observes, "The Banaras lila is world famous; they say people come from far and wide to see it."[48]

Although the Ramlila is particularly associated with the first ten days of the bright fortnight of Ashvin, not all Banaras productions fall within this period, and some do not occur during the month of Ashvin at all. The Ramnagar production begins its epic recitation on the third or fourth night of the bright half of Bhadon and has its final ceremony in the dark fortnight of Karttik, more than forty days later. Most other productions, which typically range from ten to thirty days, fall within this period, but a few do not. The lila on Panchganga Ghat, for example, does not even begin until after the Divali festival, a full fortnight after the conclusion of the Ramnagar pageant, and runs for another few weeks. Thus a dedicated lila -goer not only has a choice of numerous productions during the height of the season but can, in theory, attend a nightly performance of one or another cycle for close to three months. In 1982, on the night after the conclusion of the Ramnagar cycle, I chanced on a decorated stage in the middle of an intersection near my house. Surrounding streets were festooned with lights and lined with snack and souvenir vendors, and loudspeakers were blaring cinema music and advertisements. I soon learned that the Bharat Milap of the Khojwan Ramlila cycle, which runs on a different schedule from that of Ramnagar, was to occur later that night. When I returned to witness it I was promptly accosted by a betel seller who had been a regular at the Ramnagar plays; exclaiming delightedly, "Good! You've come too!" he added, "See brother, here in Kashi the Lord's lila goes on and on!"

Thus, it is more correct to speak of a Ramlila "season" than of a mere festival—a season that begins during the rainy month of Bhadon, runs through the transition month of Ashvin, and continues well into the

cool, autumnal month of Karttik. During this season, wooden platforms sprout like mushrooms at major crossroads and on many ghats. To a daytime visitor, these dilapidated structures hardly seem to warrant notice, but the same visitor returning at the proper hour of the night would see them transformed by rich draperies and backdrops into palaces and battlefields to be trodden by the feet of tiny gods in gilded and spangled costumes. In all, according to a recent tally, the city mounts some fifty-six annual productions, the majority of which are staged by the citizens of various neighborhoods, each of which has a local Ramlila committee. The financial arrangements are essentially as described by Hein for the Braj productions: a month or two before performances begin, the committee conducts a general collection (canda ) throughout the neighborhood, recording the amount given by each donor. Prosperous merchants may contribute substantial sums each year but, as Hein noted, a good portion of the typical pageant's budget comes from countless small donations, which make even some of the poorest citizens Ramlila patrons.[49]

The Ramlila is a small industry and supports a variety of peripheral enterprises: artisans who build effigies and create fireworks; tent houses that lend platforms, awnings, and lights; and shops that provide costumes, masks, and props. Several such establishments are located in the old brass bazaar in Thatheri Gali, and although these stores also outfit temple images and nautanki[*] troupes (another genre of folk theater), the heavy concentration of Hanuman, Ravan, and Shurpankha masks hanging from their rafters clearly advertises one of their main lines. Then there are the hawkers of lila -related toys and treats: toy bows and arrows, clay figurines of Hanuman, and small papier-mâché masks of the same design as those worn by players.

One sign of the popularity of Ramlila , and an indication that its productions attract audiences from outside their immediate localities, is the inclusion of daily schedules throughout the season in the city's Hindi newspapers. The most comprehensive listing appears on the "Banaras and Vicinity" page of Aj , the city's largest-circulation daily. The evening's program at Ramnagar is always given first, followed by that of Chitrakut—a sign of the high prestige of these two productions. Eight days before Dashahra in 1982, for example, the listings began as follows:

Figure 22.

Ramlila masks and props at the headquarters of the Khojwan

Ramlila Committee (photo courtesy of William Donner)

Kashi's Ramlila

Tuesday, 11 October

Ramnagar: Interlude on Mount Subel

Chitrakut: Fight with Jayant

Mauniji: Severing of the Nose

Daranagar: Royal Consecration

Aurangabad: Shabari's Good Fortune

Gayghat: Slaying of Khar and Dushan

Nadesar: Burning of Lanka

Ardali Bazar: Killing of Bali

Khojwan: Meeting with Nishadh

Khajwi: Meeting with Hanuman

Lahtara: Sumant's Arrival

Ashapur: Abduction of Sita

Lallapura: Janak's Arrival[50]

and so on through another forty listings. Besides highlighting the variety of episodes that might be viewed on any given night, such notices help readers keep track of the progress of various pageants, in anticipation of particular events they don't want to miss. Kumar notes that "there is a sort of consensus in every muhalla as to which lilas are of most importance, and which of middling and of low importance, and attendance conforms to this judgment."[51] Many otherwise undistinguished productions have one episode that enjoys citywide fame, such as the "Dhanush Yajna" of Laksa, the "Nakkatayya" of Chaitganj, or the "Dashami" of Chaukaghat. These attract thousands of spectators from all over the city, but each production follows its own schedule (and may even follow a different calendar, since local pandits sometimes disagree on the timing of important lunar dates), and so the newspaper listing, based on the schedules printed by each committee, is a convenient reference.

Chitrakut and the Bharat Milap

The Chitrakut Ramlila Committee is headquartered in a walled garden adjacent to the Bare Ganesh Temple in Lohatiya, the old iron bazaar, and its production is staged there and at six other locations in the northern part of Banaras—the area sometimes referred to as Kasikhand[*] and thought to represent the more ancient part of the city. "Chitrakut" is the name of a pilgrimage place on the Madhya Pradesh border where Ram is supposed to have passed much of his forest exile; it is also the name of a locality that is the site of several performances in this cycle, although it seems probable that, here as elsewhere, the locality's name derives from the play rather than vice versa.[52] As already noted, this production is widely regarded as the city's oldest and (with Ramnagar) most distinguished Ramlila . But whereas Ramnagar is famous for the whole of its thirty-one days, the twenty-one-day Chitrakut cycle enjoys its fame primarily for a single lila : the Bharat Milap ("Reunion with Bharat," reenacting Ram's triumphant return to Ayodhya and meeting with his faithful brother), which occurs on the seventeenth day of the cycle in a locality known as Nati Imli.

Two legends about the Chitrakut pageant are often cited by Banarsis to explain its popularity. The first is the story, already referred to, of its founding by Megha Bhagat and of Ram's promise that he himself would

be physically present on certain days. Some say that he promised to be present on eight days, others claim six, and still others four. All agree, however, concerning the Lord's presence at the Bharat Milap, at which Megha Bhagat is said to have had the supreme vision and surrendered his body.

The second story concerns a nineteenth-century Hanuman player who was mocked by an Englishman—in some versions, by the district collector, who brought a party of "English ladies and gentlemen" to view the native spectacle; in others, by a "Padre MacPherson" who criticized the performance as part of his attack on Hindu customs.[53] It is said that the day's lila depicted Hanuman's mission to Lanka and was held on the bank of the Varuna, the Ganga tributary that marks the city's northern limit. The Englishman, who had some knowledge of the Ramayan, mocked the religious pretensions of the play: "You say these are gods, but really they are only actors. The real Hanuman leapt across the sea; yours couldn't even cross this small river!" Accepting this challenge, the offended actor bowed before the child portraying Ram, who presented him with his ring—just as the real Ram did before dispatching Hanuman to Lanka. Then, fastening on his heavy brass mask, he strode to the edge of the Varuna—whose stream is some eighty feet wide—and attempted the impossible leap. To the astonishment of all, he succeeded, but fell down dead on the other shore. The foreigners' mockery was silenced—some versions claim that the collector officially announced that henceforth this production alone was to be regarded as the "true" Ramlila —and the actor's mask and costume were enshrined in a samadhi at the Chitrakut lila site, where they are still worshiped each year by the current Hanuman, his descendant.[54] This popular story suggests the distinction drawn by devotees between a dramatic performance and a true lila : the former is only a representation, but the latter is a realization. It also suggests the paradoxical relationship—central to Ramlila —of the player to his role. The hero is an ordinary man who is challenged to perform a superhuman feat and does so at the cost of his

life; yet the legend implies that he is able to succeed precisely because he is not, at that moment, an ordinary man. He becomes his role and "crosses over" in more ways than one.

The Chitrakut cycle begins each year on the ninth or tenth of the dark fortnight of Ashvin, some ten days after the start of the Ramnagar plays. As noted earlier, the Brahman boys chosen to be svarups are unusually young; Ram in 1983 was only nine, Lakshman and Sita a year or two younger, and the other brothers younger still. The adult characters—Hanuman, Vibhishan, Ravan, and the rest—are played by the same men year after year, and the roles are passed down in their families.

Bharat Milap

In terms of attendance, the Nati Imli Bharat Milap is probably the single biggest event in Banaras's annual festival cycle. In 1983 the superintendent of police estimated the crowd at 500,000 persons—nearly half the population of the city.[55] This astonishing participation is not a recent phenomenon; the scale of the event in the late nineteenth century is suggested by a report in the Aj of October 30, 1893, which remarked of the Milap, "It would have to be an invalid or disabled person who does not go to see it."[56] Notices often appear in the press for reserved places on adjoining housetops; there are also "Bharat Milap clubs," which rent whole roofs. Many businesses close for the day, and from early morning all roads leading into the northern half of the city are closed to vehicular traffic to facilitate the flow of crowds into the Milap area. By midday it is all but impossible to get anywhere near the site without a special guest badge from the Ramlila committee—and these are so parsimoniously distributed that one might suppose they were tickets to paradise.

The site of the Milap is a rectangular field containing a huge tamarind tree (imli ) from which the area takes its name. At each end of the field are stone platforms, connected by a slightly raised runway perhaps a hundred yards long. Each year the platforms are freshly whitewashed, the maidan is cleaned, and a processional path of crushed red stone is laid for the maharaja of Banaras and his retinue, who will approach from one of the side streets. Crowd control arrangements are particularly impressive: a bamboo barricade some fifteen feet high is erected

wherever the field fronts on a street, and the inside of the barrier is lined. by hundreds of policemen; this is to prevent a crush from the densely packed crowd, which fills surrounding streets for blocks in every direction. A police command post on the roof of an adjacent building also serves as a reception center for dignitaries and boasts a colored awning, carpets and chairs, and a booth for All-India Radio, which broadcasts live coverage of the event. Loudspeakers on nearby houses carry announcements of lost children, although all sound is tastefully hushed as the great moment approaches. The impressive discipline and clockwork timing suggest a state ceremony or the opening of the Olympic Games, yet the remarkable thing about the Milap in comparison with such events is that all the elaborate arrangements serve to bracket a performance that lasts roughly four minutes. The incongruity of this is not lost on Banarsis, who appear to take special delight in it. "The whole thing is over in the blink of an eye," one man remarked to me, "yet hundreds of thousands flock to see it, and you must go too!"

The protocol of the Milap allows for the participation of several of the city's traditional communities. On the eve of the great day, a palanquin bearing Ram and his companions is carried from Chauka Ghat (representing Lanka) to the Chitrakut enclosure (representing the Nishadh's ashram, where Ram rests for the night). The enormous wooden palanquin, brilliantly painted in designs of flowers, birds, and animals, represents the flying chariot (puspak[*]viman ) of Ravan, now utilized by the victorious Ram, and is carried by members of the merchant community, who believe that this service insures their commercial success during the year.[57] On Milap day itself, the same task is performed by 125 members of the Ahir, or milkman, caste, who dress in white and tie on red turbans symbolizing their resolve (sankalp[*] ) to carry the Lord's vehicle.[58] They assemble outside the Chitrakut enclosure, within which the boy actors are being costumed, and worship the palanquin before lifting it. Not least among the privileges that their act of service confers is admittance to the cordoned-off inner field, from which they can obtain a clear view of the climactic embrace.

Another class of functionaries are the "beautifiers" (srngariya[*] ), who supervise the costuming and makeup of the actors. These men represent a community of Gujarati silk merchants that has lived in Banaras for some five centuries. They are recognizable by distinctive turbans of

gold-brocaded purple silk; they claim that the privilege of wearing this headgear on state occasions was granted them by Emperor Akbar in appreciation for silk they provided to the Mughal court. Their prosperous community carefully maintains its ethnic identity even while it occupies a prestigious niche in its adopted city. Its members speak Hindi outside the home, but Gujarati within it—a remarkable continuity in view of the fact that, as some of the men told me, they have never been to Gujarat and have long ceased to have relatives there. Notable too is the fact that the srngariyas[*] all belong to the Pushti Marg sect, founded by Vallabhacharya, and worship Krishna as the supreme deity. Pushti Marg theology maintains the absolute supremacy of the Krishna avatar and regards Ram as only a partial manifestation; the merchants' greeting among themselves is "Jay Sri Krsna[*] !" which contrasts with the more typical Banarsi "Ram Ram" or "Jay Sita-Ram!" In Vallabhite temples special emphasis is given to the elaborate adornment (srngar[*] ) of images, which varies with the season and time of day, and the devotee charged with these arrangements is likewise known as a srngariya[*] . In Banaras, even though Krishna is not without his adherents, the silk merchants have adapted themselves to the predominant Vaishnava strain of Ram bhakti by assuming the role of costumers in this prestigious Ramlila .[59]

It was one of the srngariyas[*] , with whom I had chatted briefly while the actors were being made up, who secured my entry to the inner field at Nati Imli on Bharat Milap day in 1983—for the soldiers guarding the bamboo gate, nervous at the press of the enormous crowd outside, had ceased honoring even guest badges by the time I arrived at the enclosure. Once inside, I made my way to the vicinity of the main platform, where I found myself surrounded by prominent Ram devotees and patrons, all dressed in their finest clothes. Also present were the twenty-four Ramayanis, identifiable by broad sashes of ocher satin, who would chant from the Manas during the performance. The gleaming white platform was encircled by purple-turbaned srngariyas[*] , each equipped with a basket of flower petals.

The hour fixed for the Milap is always observed with great punctiliousness. Mehta has noted that early evening in this season is a time of special beauty, which seems to contribute to the extraordinary and otherworldly atmosphere.[60] In 1983 the appointed hour was 4:45 P.M. , and

as afternoon shadows lengthened, a flood of golden light filled the enclosure and the atmosphere of joyous anticipation became unmistakable and infectious. At about 4:30 a slowly swelling roar in the distance informed us that the palanquin had left the Chitrakut enclosure, and we strained to catch a first glimpse of it beyond the tall barricades, the massed ranks of policemen, and the sea of upturned faces. First to appear was a smaller palanquin bearing Vibhishan, the newly crowned king of Lanka. A whimsical-looking man with a long gray beard and ash-white makeup, accompanied by several small children, Vibhishan was carried to a spot close to the main platform as an honored guest. The cheer of the crowd swelled to engulf the whole square as the great viman itself came into view, seemingly borne on a flood tide of bobbing red turbans (popular lore holds that it can actually be seen to float above the milkmen's shoulders). In slow majesty it entered the field and came to rest on the farther of the linked platforms. No sooner had the cheer greeting its arrival died down than another became audible from the opposite side of the enclosure, gradually growing into a thundering chant of "Har, Har Mahadev!" and signaling the approach of the maharaja. The sight of the royal elephant, resplendent in its trappings of velvet and gold, set off another wave of cheering. Vibhuti Narayan Singh, wearing a jeweled turban and shaded by a white silk umbrella, acknowledged the crowd's greeting with a raised namaskar and rode across the length of the enclosure to circumambulate Ram's palanquin.

In the meantime, Bharat and Shatrughna had also arrived and had ascended the nearer platform. Everyone was now in place, and as the magic moment approached, the dead Lash of a great expectancy fell over the multitude. At the far end of the field, Ram and Lakshman descended from their palanquin and stood at the edge of the runway; simultaneously Bharat and Shatrughna prostrated themselves full-out on their platform. A clash of cymbals announced the presence of the Ramayanis, who began singing Tulsi's description of the scene in the familiar chant special to Ramlila . So perfectly synchronized and dramatically effective was the timing that it seemed as if an invisible clock, of which all were aware, was counting off the few remaining seconds, bringing every onlooker to a calculated emotional peak. With measured steps Ram and Lakshman began walking along the runway, but they soon broke into a trot, which gradually increased to a full run. The mass silence was replaced by a kind of involuntary and ecstatic roar, as when a crowd at a sporting event anticipates the imminent completion of a brilliant play. An instant later, the runners reached their destination and sprinted up the stone steps, where each lifted up one of the prostrate

figures and embraced him. A cloud of red and white blossoms, thrown in handfuls by the men ringing the platform, fluttered down over the embracing boys. Loud as the cheering had been, a great sound seemed to explode above it: a mixed cacophony of bells, gongs, conches, and roars of "Raja Ramcandra ki jay!" A moment later the boys realigned themselves for a second embrace, Ram with Shatrughna and Bharat with Lakshman, more cheering and more flowers. Then they formed a line, arms around one another's waist, and faced straight ahead, bestowing their much-desired darsan on the crowd facing the platform; then rotated forty-five degrees and again paused; and so on, through two complete rounds of the eight directions, each pause accompanied by an acknowledging roar from the appropriate sector.

And then it was over. The boys descended and walked to the waiting palanquin, which was soon hoisted on the shoulders of the Ahirs to proceed in slow procession to the committee's headquarters, giving darsan to tens of thousands more en route. The royal elephant departed for a rendezvous with a waiting limousine, which would speed the maharaja back to Ramnagar to supervise the delayed start of his own Ramlila . For the rest of the multitude at Nati Imli, there was little to do but stand and wait; it would be nearly an hour before the approach roads cleared enough to allow the square's human tide to flow back into the rest of the city.

The Nati Imli Bharat Milap was one of the most powerful dramatic events I had ever witnessed. Yet, as my Banarsi friends had promised, the "performance" lasted only a few moments, involved not a word of dialogue, and hinged on a single, elemental gesture. Awasthi has remarked that its extraordinary effect on spectators serves to remind us that the real power of "pantomimic lila " lies in its jhanki , or tableau.[61] It may be added that at Nati Imli there are additional factors at work: the powerful religious expectation, supported by the story of Ram's promise of physical presence on this day; the beauty and auspiciousness of the hour; the impressive, orderly arrangements; and the presence of the maharaja, who represents not only royal authority but also Shiva, patron deity of Banaras, and whose attendance is an affirmation of the city's cultural identity. There is a further sociocultural dimension too—for one may well ask why, of all the emotional events that follow the death of Ravan, the reunion with Bharat alone evokes such an ecstatic response. I return to this topic in my final chapter.

The Enthronement

Two days after Bharat Milap I attended the performance of Ram's enthronement (rajgaddi ) in the garden compound at Lohatiya. The atmosphere could hardly have been more different from that of the frenetic and spectacular Milap. The same little boys who, two days before, had been the focus of the straining eyes of a vast multitude now sat casually on an open-air stage in a small garden, surrounded by the organizers and a handful of adult actors. And even though this performance too had been announced in the newspapers and no effort was made to exclude anyone, the total attendance during the course of the evening cannot have amounted to more than a few hundred persons. Indeed, the atmosphere was so casual that I felt I was witnessing a private party staged by the organizers for their own amusement. The child actors were in full costume—gorgeous silk robes and crowns for this special night—but they hardly seemed to be in "character"; much of the time they were lounging idly on the dais or playfully chatting among themselves, seemingly oblivious of the activities of the adults. The latter were in high spirits; everyone seemed to know everyone else, and the atmosphere suggested a backstage party after a successful opening night. Yet this was neither a party nor a rehearsal, but an actual performance of the lila of Ram's enthronement. What was one to make of it?

Amid the casual ambience, the expected sequence of events did unfold, after a fashion. The chief Ramayani, Pandit Bholanath Upadhyay, invited Ram to come sit with him near a small fire altar, where they were joined by several other Brahmans. The Manas passage describing the royal consecration was sung, and then the Brahmans began chanting Vedic mantras while their leader, smiling broadly, showed Ram what to do, guiding his little hand as he spooned oblations into the fire at appropriate intervals. While the ritual proceeded, the "party" continued all around. Vibhishan lounged at one end of the dais, conversing with an elderly devotee. Bharat and Sita played guessing games, periodically dissolving into giggles; Shatrughna fell asleep. Other groups of people sat in the garden chatting and paying no attention to what was going on. Throughout most of the evening (the ceremony began after 9:00 P.M. and continued for several hours) there were, with the exception of myself, no spectators; there were only participants, either in the lila itself or in the "party" that surrounded it. As the evening wore on, I found myself increasingly puzzled by the nature of the performance I was witnessing. It seemed inconceivable that the chuckling adult participants in the fire

ceremony, much less the inattentive onlookers, actually believed that the little boys were really the divine characters of the Ramayan. Was any "willing suspension of disbelief" possible in such a casual, even chaotic atmosphere?

But when the fire ritual concluded, an interesting thing happened. Upadhyay took Ram by the hand and led him to the marble throne platform at one end of the open-air stage. Sita, Lakshman, and Bharat followed; even little Shatrughna was roused from his nap and escorted over. The red-suited Hanuman donned his enormous brass mask and stepped forward, fly whisk in hand; a glittering silk umbrella was unfurled. Suddenly everyone in the garden was attentive. A tableau had taken shape: Ramchandra was enthroned in glory, Sita at his side, in the midst of his beloved brothers and companions. It was the climactic vision of the Manas , like Tulsi's own reputed first lila ; the nearly full moon of Sharad rode in the sky overhead. The Ramayanis took their places before the dais and intoned a hymn of praise from the Gitavali , and a steady stream of neighborhood people began to file through the garden gate for darsan .

Another performance followed: a long red carpet was unrolled at the foot of the throne, and Upadhyay stood to one side of it. The adult characters in the lila —Hanuman, Sugriv, Vibhishan, and the others—formed a queue at the far end. While "Ram" lounged casually on the throne, looking boyishly amused, the chief Ramayani addressed him in the reverent and formal language of a royal minister: "Divine Majesty, King of Kings, Lord Ramchandra!" He then began presenting each player to him with a brief introduction that was both reverent and, apparently, intentionally amusing:

Your Majesty, here before you is Sugriv. You know, Lord, he is a great devotee of yours, and he has done an awful lot for you. He bit off the nose and ears of Kumbhakarna, you'll recall. [laughter from onlookers] He attacked Meghnad too, and Ravan as well, and altogether he has suffered a lot on your account! Please be merciful, and bestow your grace on him.

While this patter was delivered, the player in question executed a series of seven full-body prostrations, beginning at the far end of the carpet and ending at the foot of the throne. These were accompanied by many chuckles of amusement from onlookers, both at the mock-seriousness of the introductions and at the difficulty with which some of the players—older men in elaborate, constraining costumes and heavy masks—executed their bows. These were anything but casual, however; each pros-

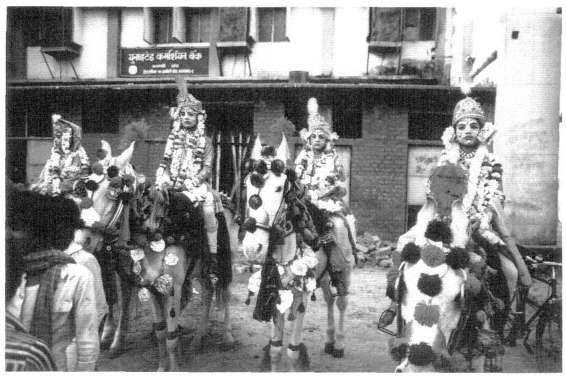

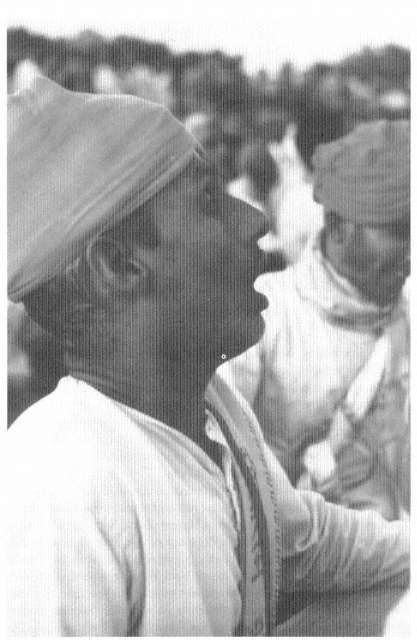

Figure 23.

A procession of boys adorned as Ramlila svarups

tration, achieved with no little huffing and puffing, was total. The man lay flat-out, arms extended toward the throne. Arriving at its foot, each player knelt and removed his mask, revealing a forehead beaded with sweat but a face grave and composed. His reward was forthcoming: the little Ram leaned forward and dropped a garland around his neck.

Reflecting on the evening's performance—on what seemed to me its incongruous conflation of high emotion and low comedy, casual ambience and occasional ritual intensity—I recalled a line from one of Hess's writings on Ramlila and its devotees: "people who grew up in easy intimacy with the God of personality and paraphernalia, the God who has characteristics like their uncles and cousins and is often as common and unheeded a household item."[62] The evening's experience had clarified a point often made by lila aficionados: that the little boys in gilded tiaras really are both children and gods. They are assumed to be guileless and innocent, free of the worries and compulsions of adults. Yet they are not merely blank screens on which devotees project the God of their imaginations; "attributes" are of the essence here, and the ones that the boys possess—innocence, physical attractiveness, Brahman-hood (equated with both social and religious prestige)—are essential ingredients in what they become. The boy chosen as a svarup is like the unblemished nim tree that the woodcarvers of Puri select, once every twelve to nineteen years, for their new image of Jagannath, Lord of the World.[63] Just as the Jagannath devotee may be aware that the image he adores was once a tree, so the Chitrakut spectator may recall, at times, that the boy beneath the crown is so-and-so's son, lives in such-and-such lane, and so forth. At the same time this boy possesses, by virtue of his attributes, the authority (adhikar ) not merely to represent but to become Ramchandra, just as the right kind of tree becomes Jagannath. And having become the part, he can offer something that every devotee craves and even temple images cannot bestow as tangibly: familiarity and intimacy with God; the chance to do seva ("service," connoting both formal worship and actual physical attention) and to experience "participation," which is one of the truest translations of the word bhakti . Each episode of the Chitrakut Ramlila affords a different kind of participation: the mass participation of the Milap, when the lila expands to incorporate the whole city and the auspicious paradigm of the

reunited brothers reaffirms familial and social hierarchies; and the intimate participation of the smaller performances, when large public symbols are replaced by near-private intimacies and grownup devotees play house with a child God.

Khojwan: Ramnagar Remade

The Ramlila of Khojwan Bazaar, a neighborhood on the southwestern outskirts of Banaras, makes claim neither to antiquity nor to originality.[64] When the current production was organized, around the beginning of the twentieth century, Khojwan was a little kasba (market town) well beyond the southern boundary of the city. Today spreading urbanization has engulfed it, but Khojwan's narrow, meandering main street, fronted by high stone buildings, strikes a contrast to the grid-patterned colonies that have sprung up around it. Every muhalla of Banaras nurtures its own sense of identity, but Khojwan's seems particularly strong. The tidy streets, flourishing bazaar, and new secondary school all bespeak municipal pride, and this is equally in evidence in the local Ramlila arrangements.

The printed announcement of this lila is the most elaborate that I have encountered. Its heading reads "Historic Ramlila of Khojwan Bazaar, Kashi," and this is followed by a paragraph summarizing the pageant's short history:

It is well known that the acts of Ram composed by Goswami Tulsidas are performed in Khojwan Bazaar for the benefit of devotees. In olden times, revered Mahatma Apadas-ji sponsored it for some days at Manasarovar, Sonarpura, Kedareshvar, and so forth; after that the late Gokul Sahu-ji, on the Mahatma's departing for heaven, with the assistance of the late Kashinath Sahu and Jagganath Sahu (the grain dealer), sponsored it in Khojwan Bazaar and for his whole life dedicated himself to it, body, mind, and fortune. Now that he has departed the world, this great work has been accomplished for sixty-six years with the will of the community and the assistance of devotees.,[65]

In her discussion of the patronage of neighborhood Ramlila productions, Kumar notes that organizers tend to fall into two categories:

(1) middle-level merchants and traders in grain, wood, metal, or cloth as well as small shopkeepers, including those of milk and pan , and (2) religious figures, whether "official" (mahant or panda[*] ) or "nonofficial" (vyas , sadhu , baba ). The former would control money through his institution; the latter would attract it through his personality. As a rule, the people of categories (1) and (2) work in association.[66]