7—

Mother Lode for the West:

California Mining Men and Methods

Duane A. Smith

High in the Colorado Rockies, snow hampered the little prospecting party as it moved slowly up a gulch from the Arkansas River. The men dug deep into gravel on this cold morning in April 1860 and called on the oldest and most experienced member of their party to pan the sand. Veteran Forty-niner Abe Lee obliged, while the rest of the group gathered around a fire to warm themselves. The rest of the story became legendary.

Noticing Lee peering intently into his pan, one of the party shouted to him, "What have you got, Abe?" "Oh, boys," he yelled, "I've just got California in this here pan." Thus the gulch and a brand new mining district had a name, California. Abe Lee had never had such luck in California, nor would he again, although he would be around long enough to be marginally involved in the later bonanza Leadville silver rush that occurred only a few miles from his 1860 discovery.[1]

This story was repeated many times throughout the West, as ex-Californians took their skills and experience over deserts and mountains in their search for gold. Abe Lee and his friends were part of a worldwide movement, yet they probably never took the time to consider, or comprehend, the California mining contribution. Nor was it only people, it was everything that could be considered part of mining—from the legend of life in the mining camps to equipment that is still being used.[2]

Fifty years after the 1848-49 rush, Alaska and the Canadian Yukon exploded on the mining scene. Maybe there were not many Forty-niners there, but their legacy arrived and stayed well into the twentieth century with the clanking dredges. Mining historian Clark Spence described it concisely: "Thus Alaska gold dredging was part of a global industry—one that looked to California for inspiration, technology, skilled labor and sometimes capital."[3] The same story, sans dredges, had been repeated scores of times earlier.

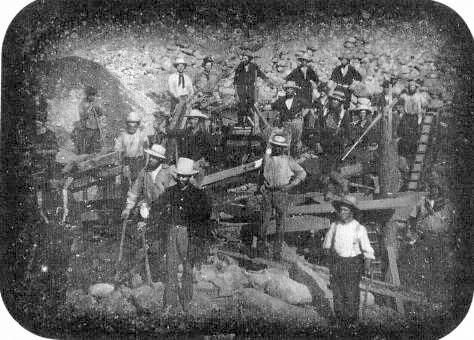

California Argonauts pause from working their claim to have their picture taken

sometime in the early 1850s. The skills and tools and techniques developed in the

mines of the Golden State were carried throughout the American West—and

indeed, the world—by prospectors who joined in the successive rushes that for half

a century kept alive the dream of a new El Dorado just over the horizon. Courtesy

California State Library .

Not that Californians were always welcome. In 1853, they were not greeted eagerly to the Australian gold rush. As historian Jay Monaghan explained, "Only a small proportion of the people coming to Australia were Californians. But Californians' bad reputation, lawlessness, revolutionary background, aggression against Mexico, and crusading determination to save the world from mobocracy by force if need be, tainted all Americans, just as the few ex-convicts from Australia had tainted all immigrants in San Francisco from down under."[4] It was a two-way street in many ways. After they returned home, Australians who had gone to California helped open the gold fields in New South Wales. Gold fever is universal.

These three examples display California's worldwide impact, but as California would give to the world, so had the state itself also borrowed from several centuries of worldwide mining experience. The cosmopolitan California rush brought together miners and mining people from throughout Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

Germans, Latin Americans, Cornishmen, Mexicans, Welsh, English, French, Spaniards, Italians, and Chinese, as well as lead miners from Wisconsin and gold miners from Georgia and North Carolina, all contributed. They helped the "pilgrims" learn the basic rudiments of mining. Mining laws, methods, mining and milling equipment, and ideas arrived along with the people in those exciting days of 1848 and 1849. Indeed, had these early Californians but realized it, many methods they used had been described (in Latin) and illustrated in 1556 by a German scholar who wrote under the name of Agricola. To these they added innovations derived from their own experiences, including hydraulicking, dredges, and water laws. This mining heritage was exported to the whole world.[5]

By the mid-1850s, the glory days of "poor man's diggings" of placer gold were beginning to pass in California. The pattern that would be repeated throughout the West had occurred. Companies and corporations now mined on a large scale; it took money to make money in mining. Already, around Grass Valley and Nevada City, hardrock mining, or burrowing into the ground after gold found in combination with other minerals, was taking place. This took skill, equipment, and finances that the average Californians did not have. They stood ready, however, poised to stampede to any new El Dorado that promised to be another California. In the generations that followed, they and their descendants did just that. Off they went, prospecting up nameless creeks, digging into any mountain that looked promising, crossing waterless deserts, and wandering on over the next ridge into any valley that seemed more enticing. With them went California's mining heritage—both placer and hardrock.

The miners themselves often remain nameless. Average folk they were, who caught mining fever and chased their dreams into a lifetime of "might-have-beens" or "used-to-bes," though these cruel epitaphs do not tell the whole story. The itinerant miners opened many parts of the West and the world, built camps and towns, created jobs, encouraged settlement, promoted the places they went, helped finance developments far beyond mining, and did more by their incessant wanderings than they ever have imagined. They changed the course of national and world history only to be buried in forgotten graves near where they toiled so enthusiastically and tirelessly. As early mining historian Charles Shinn wrote in 1884, "the migratory impulse circling outward from Sutter's ruined mill had a meaning for lands outside of North America. It ultimately became of world-wide influence."[6]

Why did they go, when there was still gold in California, though much less than they had dreamed of? Maybe it is most clearly expressed in a song about the rush to Australia. For whatever reason, miners everywhere wrote more songs that concerned California (in whatever way) than all the other mining excitements combined:

Farewell, old California, I'm going far away,

Where gold is found more plenty, in larger lumps, they say;

And climate, too, that can't be beat, no matter where you go—

Australia, that's the land for me, where all have got a show.[7]

Off they went with "their washboard on their knee."

By the end of the 1850s, the impact of former miners of the Golden State was already clearly shown. California dominated the first decade of mining in the West. Only a few small gold discoveries of local significance, primarily in Washington, Oregon, Arizona, and Nevada, challenged this dominance. Then in the spring of 1858 came news of gold discoveries along the Fraser River in British Columbia. Fraser River fever swept San Francisco and the Mother Lode country.

Perhaps more than thirty thousand rushed to the new El Dorado; we will never know the exact numbers. They commandeered anything that would float and sailed northward. Little mining camps soon sprung up, featuring a high cost of living. They tried California mining techniques only to find the river high because of melting snows; not until September would conditions be favorable. There was gold, just not as much as reports promised, and most rushers soon returned to California discouraged, many losing every penny they had gathered for the trip.[8]

Amazingly, they seemed not to be deterred by this and the earlier Kern River "humbug." The year 1859 witnessed two more major rushes, to Nevada and Colorado, in which Californians and their experience played major roles. Never again would there be such national excitement nor two major mining rushes at one time; considering all that was occurring in the United States that year with the sectional and slavery questions, 1859 would seldom be equaled in American history.

Of the two 1859 rushes, Californians particularly dominated Nevada's Comstock. "Nevada is the child of California," San Francisco's Daily Alta California (February 3, 1872) could truthfully boast. Briefly, the early Comstock story ties it completely to California. Since 1850, small placer deposits had been worked along the Carson River drainage, particularly in a place called Gold Canyon. A few Californians from west of the Sierra drifted in and out of the unpromising area, but it remained in the backwater of mining. Finally, with California and Gold Canyon placer deposits declining, prospectors moved into the mountains and early in 1859 found several deposits that they considered to be silver. Traveling over to Nevada City and Grass Valley, they had the ore assayed. The results confirmed their expectations. The ore was indeed rich in silver. They had discovered the famous Comstock silver lode.

Nevada County, one of California's most prosperous mining counties and famous for its progress in quartz and hydraulic mining, buzzed with excitement. Off went the curious, the hopeful, the investors, and many experienced mining men. They

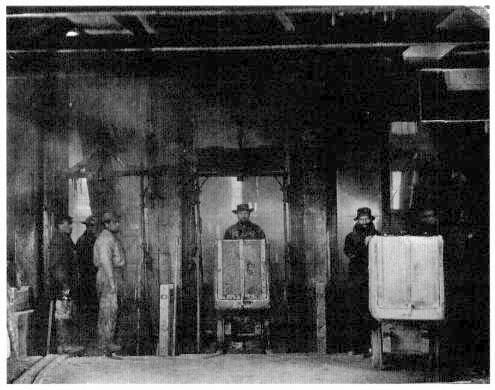

Hardrock miners enter the hoists of the Savage Silver Mining Works on the Comstock

Lode, Nevada Territory. Photographed by Timothy O'Sullivan, who illuminated the scene

in a pioneering experiment with burning magnesium wire, it is one of several images made

in February 1868 at the request of the director of the Fortieth Parallel Survey. O'Sullivan's

pictures, which also included views of the Gould & Curry Mine, were the earliest photo-

graphs to show the interior of American mines and to document the reality of hardrock

mining. Courtesy Bancroft Library .

were soon joined by other Californians, who rushed to the once-isolated Nevada diggings (at the time still in western Utah). This was almost exclusively a California rush, since the rest of the country to the east was caught up with the Pike's Peak excitement, which received even more national headlines and obviously was nearer "to the states."

The miners needed every bit of mining and milling experience, financial resources, and general knowledge in their command, because never had Californians seen anything like the Comstock. They had never encountered complex silver ore before or mined under such difficult conditions. Mining costs soared, but so did profits, beyond the best the Forty-niners had ever seen. The Comstock boomed from 1860 into 1864, helping to finance the Civil War effort for the North, and then

declined. Never losing faith, a few men kept plunging their mine shafts deeper, and in 1870 the "Big Bonanza" era opened. The Comstock and its principal town, Virginia City, again dominated the mining world. Before the bonanza days ended in the late 1870s, the Comstock made millionaires, created legends, advanced mining and smelting technology, and became the yardstick against which other districts would be measured. Admittedly incomplete production figures credit the Comstock from 1859 to 1881 with $292 million in silver and gold production.[9]

From start to finish, California's contributions proved critical and essential to the Comstock's development and prosperity. Nor was it all a one-sided street, as H. Grant Smith, lawyer and Comstock miner in his youth, explained. The Comstock "lifted California out of a disheartening depression. It rejuvenated San Francisco . . . the entire State shared in the benefits. California was the source for all supplies, from fruit to mining machinery, and every industry thrived." Also, many of the newly enriched Comstock investors were, or would become, San Franciscans.[10]

As much as California benefited, the Comstock gained even more from the relationship. That ever-observant Comstock reporter and writer, Dan De Quille (the pen name for William Wright), chronicled the early impact of Californians in his classic The Big Bonanza . They set the stage, kept the district open, and finally discovered the silver and founded the early mines. The early roads into the district all were built with California money, labor, and determination. Californians populated the early Comstock; perhaps ten thousand of them, "of all sorts and conditions," came in 1860 alone. When the Comstock miners ran into problems with the rotten rock and the huge silver veins in 1860, it was a young German mining engineer (who had been in California since 1851), Philip Deidesheimer, working in Georgetown, California, who came up with the square-set timbering system that allowed mining to continue. Square-set timbering would be an important technical feature in mining for years.[11]

Californians touched every aspect of Comstock life. As H. Grant Smith wrote in a romantic vein, "practically all of the men who came to rule the mines, the business, and the politics of Nevada had been youthful, adventurous, romantic California pioneers, and were in the prime of life; men of exceptional ability and resourcefulness, tried by hardship and ripened by experience." California and Nevada pioneer C. C. Goodwin concurred: "California drew to her golden shores the pick of the world, Nevada drew to herself the pick of California."[12] California merchants established Gold Hill's and Virginia City's major stores, operated freighting and stage lines, started newspapers, promoted the region, and even imported the first theatrical companies. They literally infused the spirit and flavor from the mining camps of California into what became the first great mining town in America's history, Virginia City. No California camp captured the attention of the American public like Virginia City did in its glory days of the 1860s and 1870s. Even budding miner and

newspaper reporter Samuel Clemens ventured out there and sympathetically and humorously described the city as he experienced it in the 1860s in his classic Comstock account, Roughing It: "It claimed a population of fifteen thousand to eighteen thousand, and all day long half of this little army swarmed the streets like bees and the other half swarmed among the drifts and tunnels of the 'Comstock,' hundreds of feet down in the earth directly under those same streets. Often we felt our chairs jar, and heard the faint boom of a blast down in the bowels of the earth under the office."[13] It was those people under Virginia City who benefited mightily from California. The state contributed what experience it had in underground mining, basically from the Grass Valley and Nevada City mines. Mining methods, experienced miners (especially some Cornish), timbering, corporation development, and equipment traveled over the Sierra, even if they did not always meet the specific needs of the Comstock.

Rossiter Raymond, an expert mining reporter and also the U.S. Commissioner of Mining Statistics, devoted a whole chapter of his 1869 report to the manufacture of mining machinery in California. He praised the San Francisco mechanical engineers, foundries, and machine-shops for "successfully meeting" the needs of broader Pacific slope mining: "Their work is characterized by great boldness, independence of precedent, ingenuity and originality; and they to-day furnish some of the best machinery in the world for certain departments of the art of mining. . . . California not only manufactures mills and machinery for the Pacific slope, for Nevada, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and Arizona, but exports to British Columbia, Mexico, Central America, South America, Colorado, North Carolina, and, to some extent, to Australia." He went on to praise California: "There is no country where so much money and effort has been expended in so short a time in experimenting with, and perfecting, the various machines used in mining."

Raymond elaborated in some detail the types of mills, tools, and machines that California was exporting to the Comstock and other out-of-the-state mining regions. The variety is amazing. These included various hydraulic mining equipment that had been pioneered in California in the 1850s, although the idea dates back at least to Roman times. The hand tools included thirty-one different mining picks and hand-drills and hammers. San Francisco manufactured explosives, including "giant powder," or dynamite, after 1867. Already they were experimenting with rock-drilling machines. Mine cars, rails, pumping engines, wagons, steam engines, hoisting machinery—the list is almost endless.

California stamp mills, according to Raymond, had become world famous, "superior to any other, and are regarded as models to be followed," and the state's manufacturers stood in the forefront of many new milling and smelting machines and ideas. Pans for grinding and amalgamating, copper-plates for saving gold and quicksilver, breakers, and ore-dressing and concentrating machines were a few that

The most famous of all San Francisco foundries and machine shops, the Union Iron Works

at First and Mission streets, sometime in the late 1860s. Founded in the Gold Rush by the

Donahue brothers, the company established its expertise in the fabrication of mining

machinery at an early date. In the 1870s, during the heyday of the Comstock Lode, the

works employed nearly two hundred molders and machinists and could pour more than

thirty tons of molten iron every two and one-half hours. Courtesy California State Library .

manufacturers and foundry men sent throughout the mining world. Raymond did admit that "it may be said there has been a great waste of material and money in the headlong, blundering way in which the progress has been made." The outcome justified the means, however, in his opinion: "the result on the whole is more satisfactory than it would probably have been by this time, if every problem had been the subject of slow and careful deliberation."[14]

Pioneer California industrialist, English-born Andrew Smith Hallidie, for example, made his own contributions—wire rope and the concept of the tram. He arrived in California in 1852 and four years later began manufacturing "metal rope" at American Bar, moving to San Francisco the next year. His cables became famous, and from them came the idea of the "endless moving rope" that proved "to be of practical advantage for freight on open hillsides and in the mines." Certainly by 1871, he was building a tram in Nevada. The Engineering and Mining Journal enthusiastically hailed the innovation: "The wire tramway seems calculated to perform work that can scarcely be expected from any railway with two rails, no matter how narrow the gauge." Hallidie later built trams in other western states and mining men hailed them as "the cheapest way to move ores on steep mountain sides."

In the Rocky Mountains, the idea would be developed and improved. California-type trams would eventually be found throughout the world. Noted mining engineer and reporter T. A. Rickard, when he toured Colorado's San Juan mining district in 1903, called them "great spider's webs . . . spanning the intermountain spaces."[15]

California mining produced two products that helped western mining, milling, and smelting. Borax, used in metal fluxing, assaying, and a variety of other ways, was sold throughout the world. Quicksilver (mercury), with its ability to seize upon and amalgamate gold dust, and to a lesser degree silver, proved very important to the placer miner and mill and smelter man. California's New Almaden quicksilver mines were America's most extensive. They shipped quicksilver around the West and overseas, an important contribution to the success of mining, milling, and smelting.[16]

Life at company-run New Almaden was quite different from other California camps, as artist and writer Mary Hallock Foote described in her journal; she pointed out another California contribution, in describing some of the people with whom her engineer husband, Arthur, worked. They were an "unmatchable group on the West Coast who were not only great engineers whom it was an education to work under, but remarkable men, cultivated, traveled, original." These men included James D. Hague, Louis and Henry Janin, Hamilton Smith, and William Ashburner. They gained experience in California mining and traveled throughout the world during their careers. San Francisco was the headquarters for many mining engineers, including Hague.[17] Along with others, like Rossiter Raymond, who has been called "the single most influential person in shaping the development of mining engineering into a respected profession," they were the ones who took mining from the school of "hard knocks" to a professionally guided industry.

British engineer and author J. H. Curie concurred. He wrote in 1905 that "there is to be had in San Francisco about the best scientific and practical mining education in the world." Curie, who pioneered in using the automobile in mining engineering, praised the contributions of these Californians:

The men who are being turned out from here usually begin their careers on the Mother Lode mines. With this groundwork, and with the practical knowledge they then gain of special branches of mining, as the use of big timbers, close concentration, electric and water powers—and, more than all, the treatment of low-grade ore, where economy is essential—it is not to be wondered at that these men soon become absolutely proficient. And so we find the young California engineer, or mine manager, going to-day to take up well-paid mining positions in Australia and South Africa.[18]

Even the legendary "honey bucket" owed a debt of gratitude to California. The question of human waste and sanitation in the mines had long troubled miners and owners and resulted in at least one California study about disease and sanitary con-

ditions. The use of abandoned rooms, drifts, and other out-of-the-way places was not conducive to good health. One solution advanced was an "underground privy car" that furnished a "practical and economical remedy." The Bureau of Mines even-many published a pamphlet on underground latrines, complete with drawings and instructions on how to make a "honey bucket." It concluded by emphatically stating that, "if the cars are kept clean and are reasonably convenient, the miners should be compelled to use them." Given the independent nature of miners, such advice was probably not always heeded.[19]

The California contribution did not end with machinery. Placer gold did not have to be worked in a milling process; ore coming from the hardrock mines had to be milled or smeltered and the gold and silver saved. This took experiments, skill, equipment, and financial backing. Initially, Nevada mine owners picked out the richest ore and, incredibly, sent it to England (Swansea, Wales) to be smelted. The lower-grade ore awaited local treatment. The solution came with the work of Almarin Paul, veteran California mining man and owner of a quartz mill in Nevada City. Throughout the winter of 1859-60, he experimented with ore. By the spring of 1860, he decided to build a stamp mill to crush the ore on the Comstock. He ordered machinery from San Francisco foundries, purchased lumber, and spent an "extraordinary" amount on transportation expenses. Paul used the California stamp mill that by 1860 offered a "reliable basic model that was capable of enlargement and further improvement to meet Comstock needs." Because the Comstock ore was basically silver and gold, it could be treated much like California gold ores. That gave Paul and other California quartz men a remarkable advantage as they pioneered milling on the Comstock. Improvements and modifications had to be made, and eventually Paul developed what became known as the "Washoe pan process," or the "Washoe pan amalgamation" process. This mechanical and simple chemical process would be transferred throughout the world wherever similar ores were found.[20] That pattern would be repeated with many Comstock ideas, inventions, and techniques, as Comstock miners and mining engineers migrated throughout the West and the world.

Because of these developments, and others that followed in the 1870s, San Francisco emerged as the "queen city" of a vast inland mineral empire. Combined with all of California, it was the source of leadership, supplies, mining equipment, and capital investment for a region that stretched from British Columbia to the northern provinces of Mexico and as far east as the Rocky Mountains.

California money underwrote much of the early Comstock developments, as experienced quartz miners and investors raced eastward to get in on the ground floor. Among the former was George Hearst, who had come west in 1850 and eventually mined at Grass Valley. He was one of the lucky ones who learned "in strictest confidence" of the wonderful silver assays from across the mountains. Hurrying

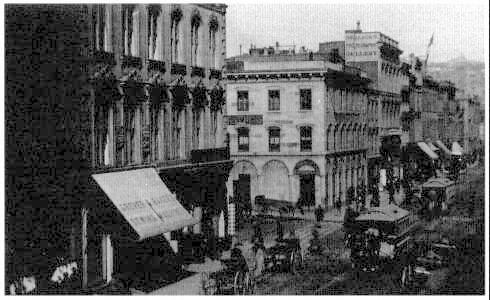

Montgomery Street, San Francisco, looking north from the Eureka Theater near the

intersection with California Street, 1865. Along this thoroughfare stood most of the

great financial institutions of' the Golden State, which provided capital for investment

in countless enterprises throughout the American West. John Parrott's Granite Block,

center, was constructed in 1852 and over the years housed such leading banks as Adams

& Co., Page, Bacon & Co., and Wells, Fargo & Co. California Historical Society,

FN-30961 .

across the range, he purchased one-sixth interest in the Ophir mine, the first bonanza. He sold his California property, borrowed money, and saw it all returned handsomely when the first shipment of silver ore paid $91,000 above smelting and transportation costs. Those Ophir silver bars convinced Californians that the bonanza had been found. They also provided the basis for the Hearst fortune. Before he finished, his investments were strung across the mining West. Hearst's money would help develop both gold in the Black Hills of South Dakota and copper in Butte, Montana.[21]

More legendary were the accomplishments of four Californians, four poor Irishmen who became the "bonanza kings" of the Comstock—John Mackay, James Fair, James Flood, and William O'Brien. Their fight to control the Comstock, a fight among California investors, is one of the epic financial struggles in mining history. All had been miners in California except O'Brien, a small-time San Francisco businessman who eventually became a partner with Flood in a saloon. Mackay and Fair migrated to the Comstock, and ultimately the four teamed up.

The story does not start with them, however. Rather, it begins with William Rai-

ston, the speculative genius who in 1864 helped organize the Bank of California, which soon became the leading financial institution of the Far West. As the Comstock slipped from rich ore into borrasca (barren rock) that same year and the next, the bank suffered some serious overdrafts in its Virginia City branch. Ralston sent William Sharon, a shrewd, cynical, mining and stock speculator, to Virginia City as branch manager and agent. Behind these two stood most of the "big names" in San Francisco finance. Sharon recovered the money and became convinced that with some shrewd planning the bank could monopolize the district and reverse the Com-stocks fortunes.[22]

After some discussion and disagreement with the bank's board, the effort was started. Sharon's plan was simple in design, complex to carry out. First, he lent money at lower interest to milling, smelting, and mining companies; then, when they could not make a payment, he ruthlessly foreclosed on their properties. The mills and smelters fell first, and Ralston soon acquired a near monopoly and relocated the reduction works to the Carson River, with its water power. To reduce transportation costs, Ralston and Sharon in 1869-70 built the Virginia and Truckee Railroad, which tied into the Central Pacific at Reno. They then moved to control the companies that brought lumber and water to the Comstock. Criticism of the "bank crowd" and its various monopolies became legendary as Comstockers forgot that the banks heavy investments during these disheartening years gave the district and Virginia City a needed boost and hastened the coming of the revival.

The challenge to Ralston and Sharon came from two groups, the "bonanza kings" and two other Californians, Alvinza Hayward and John Jones. Through a series of stock manipulations and trading, and inside information, the two groups broke the Ralston/Sharon monopoly in the early 1870s and brought in the era of the "Big Bonanza." In the end, both San Francisco and the Comstock benefited, although Ralston went bankrupt.

The four Irishmen gained control of the greatest of the Comstock mines, the Consolidated Virginia, and promptly became multimillionaires. Of them, Comstock historian H. Grant Smith said that "the members of the Firm played a fairer game than any other group in control of Comstock mines." They did more extensive "deep work" than any other group, and "they paid dividends whenever it was possible." Eighty million of the $125 million in dividends paid by Comstock mines came from their mines.[23]

San Francisco emerged as the mining investment and stock center of the Pacific Coast, and its money went throughout Nevada and elsewhere in the mining West. Not always were the investments successful. An interesting story is that of Adolph Sutro, who arrived in California in 1851 and joined the Comstock rush. His dream was to dig a tunnel under the Comstock to drain groundwater from the mines, provide a passageway for ore to the Carson River mills, and supply needed ventilation

The works of the Gould & Curry Mine at Virginia City, one of the many hardrock enterprises

on the Comstock underwritten by California investors, 1865. Courtesy Huntington Library,

San Marino, Calif .

for the increasingly hot, humid mines. Financial, technical, and political problems slowed him, and although begun in 1869, his tunnel did not reach the Comstock's main mines until 1878. He managed to depart a millionaire, but the tunnel never proved financially successful.[24]

Financial manipulations such as these were not unique to California. California investors became masters of the "game," however, and would be found throughout the West in the years that followed. Companies incorporated in California were a trademark of many western mining districts. The same proved true of the emergence of San Francisco as a mining manufacturing center. California mining equipment

would be found everywhere, but especially in the states of Idaho and Nevada, both of which had direct transportation connections and multiple ties to California.

Comstock excitement and success created interest in the rest of Nevada. Prospectors, followed by miners and investors, scurried over desert valleys and mountains searching for the next Comstock. Along with them came more California experience and money. W. Turrentine Jackson observed that California capital moved into the Austin and Eureka districts, two of the most prominent Nevada strikes in the 1860s after the Comstock. Not every district so benefited. Treasure Hill in eastern Nevada, much to the dismay of locals, did not receive much California money. But mining methods developed in California and the Comstock were found there, and everywhere. California newspapers "boomed" each new Nevada discovery, and Californians' interest was whetted by each new "Comstock." "Ho for the Reese River [Austin]," they read, along with Pioche, Tuscarora, Belmont, and places between. For more than two generations, Nevada and California were close mining partners.

Eureka was typical of the pattern that occurred in Nevada. There, California money and experience helped develop transportation, mines, and smelting. San Francisco capitalists purchased the major mines and helped develop the Eureka district into second place in production behind the Comstock. Because this was a lead and silver district, new smelting methods had to be developed, and Eureka emerged as one of the foremost smelting districts in the entire West. Smelting methods developed here went directly to Colorado's Leadville and San Juan mining districts, displaying how California's influence went well beyond its immediate physical and financial impact.[25]

Nor did it stop with the end of the century. Californians were there, along with their money, experience, and machinery, in Goldfield and Tonopah, Nevada, in the early 1900s. They purchased, developed, and speculated in these gold and silver districts and helped one more time to boom Nevada's mining industry. As in 1849 and again on the Comstock, the production of the Tonopah and Goldfield areas, Nevada historian Russell Elliott concluded, "had a pronounced effect on the total gold and silver production of the United States." The Comstock in 1875 accounted for 75 percent of American production; Nevada accounted for 20 percent in 1910.[26]

Colorado's connection to California was not nearly as close as Nevada's. At first, the Pike's Peak gold rush of 1859 completely overshadowed the slower-to-develop and farther-from-the-East excitement at the Comstock. "Pike's Peak or Bust" attracted the attention of the eastern press and easterners. They came in near record numbers that spring—100,000 people, give or take a few—second only to the numbers of 1849. Because Californians became enamored with the potential of the Comstock, and because California investment and manufacturing centers were far away, Coloradans looked to the Midwest, the East, and Europe for support.

Nevertheless, Californians played an important role in the early discoveries of Colorado gold. A group of Cherokees from Indian Territory, en route to the California gold fields in 1850, found a small amount of gold near what would become Denver. Subsequently, having little luck in California's Mother Lode country, they returned home but did not forget what they had found along the Rocky Mountains. In 1858 they returned to the Rocky Mountains, led by William Russell, an experienced Georgia and California miner. The few hundred dollars worth of gold they found became the incident igniting the 1859 rush. "The New Eldorado!!!! Gold in Kansas Territory," screamed midwestern and eastern newspapers, and the rush was on in the spring. It would have been the "hoax" that some people predicted, if other experienced California miners had not found several more promising discoveries during the winter of 1858-59. George Jackson and John Gregory struck gold near present-day Idaho Springs and Central City. While they tried to keep their finds secret, by May 1859 the word was out, and Colorado's mining future leaped from questionable to boom.

Among the "Fifty-niners" who rushed westward were a few Forty-niners whose knowledge of placer mining helped the storekeepers, farmers, and other would-be miners work through the early trials and tribulations of the Pike's Peak country. As Rodman Paul observed, "former Californians and Georgians were their instructors; from these veterans of earlier mining frontiers the inexperienced multitude learned just enough to get started." Unfortunately, however, Colorado's placer deposits were neither as rich nor as large as California's, and within months Coloradans turned to quartz mining. Here, "since so many of the 'Old Californians' of the Colorado rush had in fact left California several years previously, they were not familiar with the technical progress that came with the maturing of mining on the Pacific Coast." Colorado miners were thus doomed to repeat some of the same mining and milling mistakes and other experiences of California.[27]

They were not doomed to repeat everything, however. One of the significant contributions of Californians was the development of the concept of mining districts and mining law. The need to provide a basis for claim ownership and registration, and a fundamental mining law structure, had caused these developments. They wanted nothing costly or detailed, only a system that could be easily understood and function with rudimentary democracy. Again the Californians drew on worldwide experience in addition to their own as they scattered throughout the West taking the ideas with them.

The first mining district, created June 8, 1859, in present-day Gilpin County, Colorado, shows the influence of Fifty-niners and their California experience. The boundaries of the Gregory District were defined, the number of claims an individual could stake limited (to one), the rules for staking and registering claims specified, the rights of companies defined, and the rules for settling disputes in a miner's court

(with a three-man jury) described. The costs were small, $1 for registering a claim and $5 each for the secretary and "referees" for "their services" in settling a dispute. These first "laws and regulations" would be expanded at a July 16, 1859, meeting, and later as needed. Out of the experience of Gregory District and scores of other districts throughout the West would eventually come the federal mining laws in 1866, 1870, and finally 1872. Mining Commissioner Raymond hailed the "eminently wise and salutary" 1872 measure. "Doubtless some minor points in the bill would be found to require modification to insure its smooth working. Those may be left to the indications of future experience." William Stewart, the U.S. Senator from Nevada, led a determined battle to help bring this about. A former California miner, lawyer, and mining law expert, Stewart had transferred his career to the Comstock and on to Washington. Raymond congratulated him for displaying both "courage and judgment in its preparation." That 1872 mining law is still the "law of the land."[28]

One of the most significant impacts of California and Colorado on western mining would be the development of water law, the doctrine of prior appropriation, or "first in time, first in right." The use of water was critical to placer operations, and that water could not be turned into the consistency of "liquid mud" by the work of miners higher up the stream. Water conditions affected the rights of quartz miners and mill and smelter men as well. California wrestled with the problem in the 1850s and Colorado faced it soon after the 1859 rush. The Gilpin County meeting of June 8 defined a basic principle—"in all cases priority of claim when honestly carried out shall be respected"—and "resolved" that, for quartz mining purposes, no one could use more than half the water of a stream. A February 1860 meeting produced a series of more detailed sections on water rights, including "that when water is claimed for Gulch and quartz Mining purposes on the same stream neither shall have the right to more than one-half unless there shall be insufficient for both, when priority of claims shall determine" and "that all other questions not settled by the provisions of this act, arising out of the rights of Riparian proprietors shall be decided by or in accordance with the provisions of the Common Law." It would not be until the 1870s in Colorado that finally the water conflicts between mining, agriculture, and urban needs would bring the issue to a head. The Colorado Supreme Court in 1872 laid down the basis for what became the "Colorado System," which was adopted throughout much of the West.[29]

Colorado also used California technology, a point Rodman Paul clearly brought out in his vanguard 1960 essay, "Colorado as a Pioneer of Science in the Mining West." Some of the earliest mining equipment, including simple stamp mills, although they came from Iowa, were manufactured from plans obtained from experienced San Francisco manufacturers. Modifications soon appeared, and California's technological influence diminished after the early 1860s, although in a few cases where similar types of ores were found, machinery and milling practices were almost

identical. California- and Nevada-trained mining men and miners continued coming to Colorado in the following decades. As mentioned earlier, along with them came Eureka, Nevada, smelting and other techniques and equipment. Colorado would make its own contributions in the use of electricity, trams, power drills, and particularly in the scientific approach to smelting and mining gained from metallurgists, geologists, and chemists, but Colorado's start reflected California precedents.[30]

California was the "pioneer teacher" for its two most important rivals, Nevada and Colorado. Each state made contributions, along with other western states, to the advancement of the mining industry. "Within a generation, [they] transformed American miners from unskilled operators into mining specialists whose services were sought in all parts of the world." By the turn of the century, Americans and American equipment had moved into the front rank of mining.

Unfortunately, California contributed something else to Colorado: mining speculators and speculation. It might have happened anyway, but the experienced Californians raced to pick up pieces of Colorado's wealth before it was too late. George D. Roberts, a ruthless sort who cut his teeth on California and Nevada mining speculations and the 1872 "diamond hoax" in northwestern Colorado, arrived. Along with George Daly, and some others of his crowd, they worked in booming Leadville and the nearby Ten Mile District. Of Roberts, it has been said that he was "a prosperous San Franciscan with—to be charitable—a shady past," who left in his wake "the shipwrecks of mines, reputations, and fortunes." Before he finished, two famous mines, the Chrysolite and the Robinson, lay in ruins.[31]

In contrast to Roberts, George Hearst helped develop two of the great western mines, Butte's Anaconda and Lead's Homestake. Experienced California miner Marcus Daly, who had also worked at the Comstock and in Utah, had taken Hearst and several of his wealthy California associates to Butte. These investors' money in the early 1880s allowed Daly to spend the funds necessary to develop the Anaconda into one of the country's famous mass-production copper mines using refined smelting techniques. They almost single handedly put Butte on the road to becoming a world famous copper center. A few years previous, during the Black Hills gold rush, the same group had purchased the Homestake claim, near Deadwood. They developed this mine into one of the world's greatest, and established the model company town of Lead.[32]

George Roberts gave California mining investors a bad reputation, but the industry needed the promotion and finance that such people and their contemporaries contributed. As historians Clark Spence and W. Turrentine Jackson have shown, California's mining promoters were active throughout the second half of the nineteenth century in England and Scotland.[33] The record is a mixed one, but that was as much the fault of overenthusiastic, naive, and greedy investors as it was of unprincipled and unscrupulous speculators. Without the promotion and financial

support of these men, and a few women, such as Ferminia Sarras, Ellen Cashman, and Laura Swickhimer, mining would not have developed at the pace and to the extent that it did during these years.

Californians would be found in all the western mining states, but not with the impact they had in neighboring Nevada. J. Ross Browne, a contemporary of Raymond and also a well-known writer and mining reporter, observed that, when discoveries were made in Idaho in 1861 and 1862, the region was initially looked upon "as a theater for speculation and as a place for a temporary residence"; therefore, people returned to either the Pacific or Atlantic states with their fortunes. This transitory lifestyle shaped much of the West, at least in the early years of new districts. It was the case in California in 1849, in Colorado in 1859, and in Alaska in 1898. In 1867, however, Browne had hopes that this was changing, that Idaho would attract permanent settlement, and the territory would eventually be able to maintain itself. California, in this instance, contributed agricultural products and also mining knowledge and equipment.

Veteran California prospectors and miners, who helped open the Idaho mines, repeated the process, crossing the mountains into neighboring Montana, a familiar pattern in the West. Browne, however, warned that the California experience could be taken too far. "In California nearly all the gold-bearing veins are quartz, and the prospectors hardly ever prospect for anything else." Gold, he observed, is found in "slate and porphyry" in Idaho. It was a warning well taken, but he also knew that Californians could adjust. "The skill of some prospectors," he reported, "is wonderful in determining the existence and locality of small veins covered deep under the soil."[34]

Idaho had its "golden age" in the 1860s. With California placers declining and Colorado's not matching expectations, Idaho and Montana became the "poor man's diggings." Both regions eventually turned to quartz mining, and corporation control developed there as elsewhere. California money and experience spread to both. The silver mines developed in the 1890s in Idaho's Coeur d'Alene also benefited. Even across the Canadian border, in Rossland and small mining districts such as Sandon and Silverton, California influence reached, albeit generally, and indirectly. Meanwhile, Californians and California-experienced miners scattered throughout the West, chasing their golden and silver dreams as the Forty-niners had done before them. Prospector Henry Wickenburg discovered Arizona's Vulture Mine in 1863, and Ed Schieffelen the Tombstone silver deposits in 1877. These two helped open Arizona to mining, but in the end, despite legendary and romantic contributions, it was the George Hearsts of the West who developed the prospectors' discoveries and profited the most from them.[35]

California placer and hardrock mining might have been in decline by the turn of the century, but California's influence was not. The floating California dredge, for in-

The dredge Phoenix at work on the Yuba River, about 1850, as portrayed by William N.

Bartholomew. The machine—one of the first—was described by J. Wesley Jones, who

traveled west with the artist, as "a Cumbrous arrangement, by which it was designed to

drag up sand from the bed of the river, and obtain gold in large quantities." According to

Jones, the Phoenix was abandoned after it was found to have "dredged more Money from

the pockets of the owners than it did gold." Dredging ultimately proved highly profitable,

and following the turn of the century the "California dredge" came to dominate the industry

worldwide. California Historical Society .

stance, became world famous. Californians had been tinkering with the dredge idea since 1850. It was part of their effort to move more gold-bearing gravel with less work and more profit, particularly from river bottoms and banks. These early efforts produced, as dredge historian Clark Spence noted, a "never-ending line of ingenious and sometimes bizarre equipment, with one failure after another consigned to the scrap heap until the late nineties." Finally, by combining ideas from New Zealand and Montana, the "hybrid California-type" dredge appeared, superior to all its ancestors. It became the "standard for a global mining industry and a significant export item."[36]

Basically, the dredge applied the notion of mass production to mining. It offered the low cost and versatility to handle low-grade ores. Mining engineer Arthur Lakes, Jr., described it in 1909: "A gold dredge consists of a floating hull with a superstructure, a digging ladder, [an] endless chain of digging buckets, screening apparatus, gold-saving devices, pumps and stacker. It could be described as a floating mill with

the addition of apparatus for excavating and elevating the ore." California set the pace, not only for manufacture, but for use. In 1910, for example, 72 of the 113 dredges operating in the United States dug in California districts. Even more significant was the complete dominance of the California dredge. In 1915, only 11 out of a total of 225 dredges in use throughout the world were not American-made. Even if not manufactured in California, they were based on California's experience. In time, these dredges operated from Nigeria to Korea, from Portugal to the Philippine Islands. By mid-1932, they could be found in the Soviet Union; 22 new California dredges worked in Soviet placer fields. The California dredge had conquered the world. "The California-type dredge, known all over the world, is so efficient that it is being used on every continent where large quantities of low-grade metals are found." [37]

It might have conquered the world, but the dredge did not conquer everyone's heart. As Robert Service watched the device tear up the Klondike, where only a few years before the Ninety-eighters had prospected, he wrote from the viewpoint of one of those pioneers:

There were piles and piles of tailings where we toiled with pick and pan

and turning round a bend I heard a roar,

And there a giant gold-ship of the very newest plan

Was tearing chunks of pay-dirt from the shore.

It was the triumph of corporations and, as Service observed, "Ah, old-time miner, here's your doom!" [38]

Service was right on both counts: the old days were gone and, tragically, the environment's balance as well. The dredge's "bill of fare was rock and sand; the tailings were its dung." That dung, the piles of washed rock snaking along wherever the dredge dug, can be seen throughout the world. Therein lies another contribution of California. Not only did California pioneer in American mining, it pioneered in environmental awareness, even if that term may have been foreign to the nineteenth century.

Hydraulic mining, using a powerful hose and high water pressure to wash gravel, was carried on extensively in California by the 1870s. While it turned a profit and allowed lower-grade deposits to be worked, it also created major problems. Tailings obstructed the river, causing flooding that ruined agricultural land in the valleys and threatened towns. The issue came to a head in the Feather River Valley and at Marysville, which had been suffering damage from floods and hydraulic debris since the early 1860s. With residents unable to manage the altered river's behavior, and facing even further flood damage despite building higher levees to protect the town and surrounding lands, the dispute entered the federal courts. Local resident Edwards Woodruff sued some of the responsible mining companies, and the case of Woodruff v. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Co . forced the industry to defend itself.

It was a contest between the emerging agricultural and urban California versus the mining industry that had created the state.

At the trial, both sides presented economic, social, and emotional arguments, not to mention threats to support their positions. Finally, on January 7, 1884, in a landmark case, U.S. Circuit Court Judge Lorenzo Sawyer, coincidentally a Forty-niner, "perpetually enjoined and restrained" the North Bloomfield Company "from discharging or dumping into the Yuba or its tributaries." As no place existed where the mining companies could profitably dump the tailings, they were forced to cease operation. An era ended that day. Times had changed, but mining methods had not changed with them. The ruling implied that miners no longer represented California's present and future. The industry no longer drew the population or wielded the economic and political power to impose its will. The legal case marked the first skirmish of a war over broad environmental policy that would become heated a century later. [39]

The industry should have taken notice a decade earlier in Oakland. There residents objected to building a smelter in the city. Opposition centered on the offensive fumes, which would "poison our pure air" and render this "beautiful city an undesirable place to live." The city council heard complaints and, finally, on March 6, 1872, declared it would welcome all smelting works except those producing gases that would be harmful to the health of "her inhabitants." No smelter came to Oakland.

California might have "pioneered" in the environmental fight, but California's nineteenth-century miners were no pioneers in cleaning up the environment. For thousands of years, miners had dug into the earth without being challenged, so why should they pay heed now? Nor did other western miners and smelter men show any more interest when they were challenged in Salt Lake City, Denver, and Butte. They "sowed the wind and they shall reap whirlwind." [40]

California was more than the Mother Lode country. It was the mother of western and to a lesser degree, world mining. This was claimed early by the Californians, a product of local boosterism as much as a reflection of the facts. However, outside observers noted the same trend. J. Ross Browne, in his 1866 report as U.S. commissioner for the collection of mining statistics, spent almost the entire first section of it discussing California's contribution to the migration of people, ideas, equipment, and finances in other mining districts. Mistakes had been made, but the future was bright with promise. [41] That optimism was also a heritage of California—over the next mountain, in the next canyon, would be E1 Dorado.

Those ubiquitous veterans of the Sierra mines, the "old Californians," went everywhere carrying with them their craft of mining. They did more than that, however. They influenced regional life, the life of the mining camp and the town. The materialistic, boisterous, transient conditions of California mining communities would be re-created throughout the mining West. Perhaps Charles Shinn said it best when he

wrote more than a hundred years ago that, "out of the [mining] camps of old, powerful currents have flowed into the remotest valley of the western third of the American continent. We may even seek the great cities, whither all currents flow,—New York, London, Paris, Berlin, St. Petersburg." [42]

California exported something else as well, a dream: a legend—"the days of '49." Call it nostalgia for a time passed, or perhaps one that had never really been. Maybe the Forty-niners remembered more than actually happened, but for whatever reason, the Gold Rush has become part of the American heritage, of American folklore. The entire nation felt the pull of the West. The last verse of a popular song, "Old Forty-Nine," concludes:

But now, alas! Those times have flown,

We ne'er shall see them more, sir,

But let us do the best we can,

And dig for golden ore, sir,

And if we strike a "decent lead"

Let's work and not repine, sir,

But take things easy as they did

In good old forty-nine, sir.